Abstract

The cynomolgus macaque model of low-dose Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection recapitulates clinical aspects of human tuberculosis pathology, but it is unknown whether the 2 systems are sufficiently similar that host-based signatures of tuberculosis will be predictive across species. By blind prediction, we demonstrate that a subset of genes comprising a human signature for tuberculosis risk is simultaneously predictive in humans and macaques and prospectively discriminates progressor from controller animals 3–6 weeks after infection. Further analysis yielded a 3-gene signature involving PRDX2 that predicts tuberculosis progression in macaques 10 days after challenge, suggesting novel pathways that define protective responses to M. tuberculosis.

Keywords: tuberculosis, cynomolgus macaque model, blood transcriptomics

Blood RNA Signatures Prospectively Discriminate Controllers From Progressors Early After Low-Dose Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection of Cynomolgus Macaques.

Tuberculosis remains a major cause of global mortality and morbidity, with an estimated 1.4 million deaths in 2015 [1]. An animal model that accurately recapitulates the relevant aspects of human Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection and disease is a necessary tool for developing interventions that can achieve the goal of tuberculosis eradication. Infection of cynomolgus macaques with a low dose of Mtb leads to the full spectrum of clinical outcomes observed in humans [2, 3], where animals either control Mtb and develop latent infection (57% = controllers) or progress to active disease (43% = progressors) within 6 months of infection [3], binary definitions of outcome that simplify the true spectrum of infection outcomes in humans and macaques [4–6]. Importantly, the macaque model offers the unique opportunity to assess host responses at early serial time points after Mtb infection while controlling inoculum dose and strain, providing an opportunity to identify critical host responses that predict the outcome of infection and offer new insights into the human response.

Blood transcriptional profiling has proven to be a valuable tool for studying the human response to Mtb infection, enabling diagnosis of active tuberculosis disease [7], tracking the response to tuberculosis treatment [8], and predicting risk of progression to active tuberculosis disease [9]. Recently, whole blood transcriptomes in the cynomolgus macaque model of low-dose Mtb infection were analyzed and found to reproduce many aspects of the human tuberculosis response and revealed important features at very early time points [10], which are currently not possible to analyze in humans.

In this study, we demonstrate that a subset of genes from a previously published transcriptional signature predicting tuberculosis progression in humans [9] also prospectively discriminates progressor macaques from controllers, early after challenge. Furthermore, we identify and validate a novel 3-gene signature, measured only 10 days after challenge, that also discriminates these groups of animals and implicates new biological processes in the control of Mtb. These results further confirm the low-dose challenge nonhuman primate system as a suitable model for tuberculosis progression in humans, confirm the broad applicability of a subset of genes in the human tuberculosis risk signature, and suggest previously unidentified genes and pathways that may play a role in protection early after Mtb infection.

METHODS

Ethics Statement

All experimental manipulations, protocols, and care of the animals were approved by the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, protocol assurance number A3187-01 (specific protocol approval numbers 11090030 and 1105870).

Animals

Adult cynomolgus macaques (Macacca fascicularis; Valley Biosystems, Sacramento, CA) were housed within a Biosafety Level 3 primate facility after low-dose infection with Mtb (Erdman strain) and were clinically classified to have latent infection (n = 31) or active disease (n = 27), as described [10]. At the time that infection outcome was declared, animals underwent positron emission tomography – computed tomography (PET-CT) scan, and lung inflammation was quantified using lung 18F-flurodeoxyglucose (FDG) activity [10].

Blood was sampled serially from the macaques before Mtb infection and on days 3, 7, 10, 20, 30, 43, 56, 90, 120, 150, and 180 after infection [10]. Samples from macaques from the previous study [10] were apportioned to the training set (n = 38), and samples from 20 previously unanalyzed macaques formed the test set (n = 20). A summary showing the number of samples available is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Transcriptional Profiling

Microarray analysis of training set samples has been previously described [10]. Multiplex quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed on total RNA samples from both the training [10] and test sets as previously described [9].

Statistical Analysis

Classifier predictive performance was quantified using Wilcoxon rank sum statistics and the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUC). P values were corrected for multiple hypothesis testing using the method of Benjamini-Hochberg. Predictive signatures were developed using the pair ratio algorithm (Supplementary Methods).

RESULTS

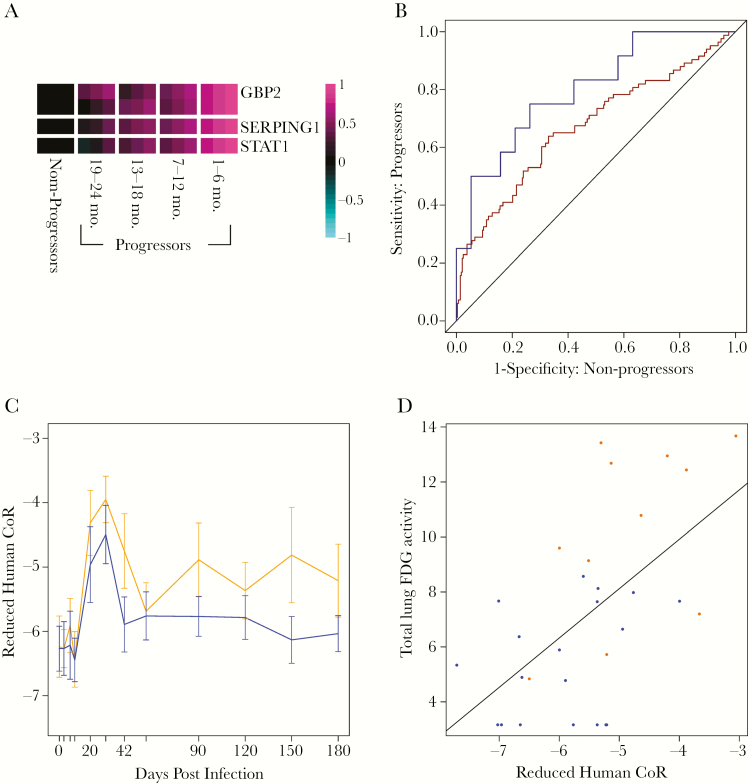

Prediction of Tuberculosis Progression in Macaques Using a Subset of Genes from the Human Correlate of Risk

We recently reported a whole blood RNA-based correlate of risk (CoR) for predicting which Mtb-exposed individuals are most likely to progress to active tuberculosis [9]. This signature was discovered by RNA-Seq analysis of a cohort of latently infected South African adolescents (the Adolescent Cohort Study) and validated by blind prediction using qRT-PCR analysis of samples collected from adult household contacts of tuberculosis index cases from multiple African sites. To determine whether this human-derived signature (human CoR) is also predictive for progression to active tuberculosis in macaques, we tested it in the macaque system. Those human qRT-PCR assays that reliably detected transcripts in blinded cynomolgus macaque blood RNA samples were selected to yield a cross-species reduced CoR. This reduced CoR comprised 4 primer sets from 3 of the original human CoR genes (GBP2, SERPING1, and STAT1) (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table 2, Supplementary Methods). Despite containing a smaller number of genes, the reduced CoR displayed no appreciable reduction in prediction accuracy when applied back to the original human validation cohort (Figure 1B) (ROC AUC = 0.67; P < 10–6). When this reduced CoR blindly predicted tuberculosis progression within the training cohort of 38 Mtb-infected macaques, significant prediction (FDR < 10%) was achieved at 5 of 12 time points (Supplementary Table 3). The earliest significant prediction was observed at 20 days after infection (ROC AUC = 0.68), and high accuracy was achieved at 42 days after infection (Figure 1B) (ROC AUC = 0.80), 6 weeks before any macaques were diagnosed with active tuberculosis. Although the statistical significance of the predictions varied across time points, prediction accuracy (ROC AUC) was comparable to or superior to that observed in the human cohorts [9] at all time points more than 20 days after infection, with 1 exception (day 56). Although the reduced CoR score discriminated between progressor and controller, the kinetic profile of the score after challenge was comparable between these 2 groups, exhibiting an initial peak at days 20–30 after infection, and then relaxing to set points that either differed (progressor macaques) or did not differ (controller macaques) from the initial prechallenge levels (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

The human transcriptional correlate of risk (CoR) for tuberculosis progression predicts which Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)–infected macaques will develop active tuberculosis and which will develop latent infection. A, Heatmap visualization of expression of the genes comprising the reduced CoR signature during progression to active tuberculosis in humans, using data from [9]. Log2 quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction expression data are shown for progressors as a function of time before tuberculosis diagnosis and for nonprogressors. Rows are scaled by subtracting the average expression levels for nonprogressors and then dividing by the maximum absolute observed value. For each group, the mean (central column) +/- standard error of the mean (right/left columns) is plotted. Two primer sets from GBP2 were retained in the reduced CoR, as indicated by the 2 rows in the heatmap. Pink indicates higher expression compared to controls. B, The reduced CoR signature simultaneously predicts progression in the human test set of African household contacts (red receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve; area under the curve [AUC] = 0.67; P = 9.7 × 10-7; data from [9]) and in Mtb-challenged macaques on day 42 after infection (blue ROC curve; AUC = 0.80, P = .002). C, Scores for the human reduced CoR signature are plotted over time after Mtb challenge for macaques that will develop active tuberculosis (orange) and those that will develop latent infection (blue). The mean (+/-95% confidence interval) is plotted. D, The reduced CoR score at day 42 after infection correlates with lung 18F-flurodeoxyglucose activity as measured by Positron Emission Tomography – Computed Tomography (PET-CT) on the day of clinical diagnosis (Spearman ρ = .52; P = .003). Orange points indicate macaques that progress to active tuberculosis; blue points indicate macaques that develop latent infection. Abbreviations: CoR, correlate of risk; PET-CT, positron emission tomography – computed tomography.

To better understand how the reduced CoR score relates to inflammatory processes, we compared it to lung FDG activity measurements quantified by PET-CT scan, which provides a readout of pulmonary inflammation in macaques [10]. Lung FDG activity at the time of clinical diagnosis was significantly correlated to scores from the reduced CoR when compared contemporaneously (Supplementary Figure 1) (Spearman ρ = .55; P = .001). Correlation was observed as early as day 20, with the strongest association at day 42 (Supplementary Table 4). These results indicate that the reduced CoR provides a sensitive and prospective peripheral readout for inflammatory processes that are developing within the Mtb-infected lung.

Predicting Tuberculosis Disease Progression Early After Infection Using Novel Signatures

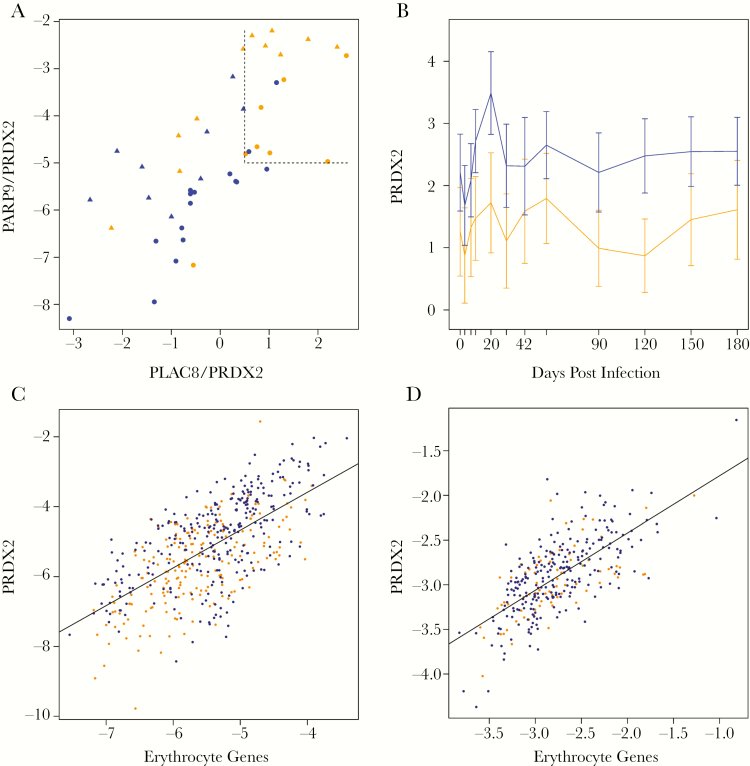

We next determined whether novel signatures could be discovered that prospectively discriminate progressors from controllers at even earlier time points than was achieved with the reduced CoR. Signature discovery involved reanalysis of the published gene expression microarray data from the 38 training set macaques to select candidate genes and then multivariate modeling of training set qRT-PCR measurements for candidate genes and genes from the reduced CoR (Supplementary Methods). Given that changes in innate and adaptive immunity with distinct kinetics may be revealed in the blood transcriptome, this analysis was performed on a broad range of time points after infection. Leave-one-out cross-validation analysis of the training set revealed strong predictive capacity at 8 time points (Supplementary Table 5; Supplementary Methods) for which 8 candidate signatures were developed (Supplementary Tables 6–13). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction profiles for the genes comprising the signatures were then generated using whole blood RNA samples collected from an independent test set of 20 Mtb-challenged macaques, and blind predictions were made using each signature. Statistically significant prediction (FDR < 10%) of tuberculosis progression was achieved for 5 of 8 signatures (Supplementary Table 14). The validated signatures included 3 additional genes from the original human CoR [9] (GBP1, FCGR1A, TRAFD1), providing additional confirmation of the human CoR genes in the macaque system. Notably, the signature derived using data from day 10 after infection (“Day 10 signature”, Supplementary Table 8) achieved high prediction accuracy using only 3 genes (ROC AUC = 0.81). This signature predicts tuberculosis progression earlier than the reduced CoR and achieves 100% specificity and 55% sensitivity on the test set at the optimal operating point (Figure 2A). Using human RNA-Seq data from the original adolescent tuberculosis progression study [9], we confirmed that the day 10 signature also predicts tuberculosis progression in humans (Supplementary Figure 2) (ROC AUC = 0.67; P = 5 × 10-6).

Figure 2.

A novel 3-gene signature predicts progression to active tuberculosis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)–challenged macaques using blood expression measurements collected 10 days after challenge. A, Scatterplot depicting how the 2 gene ratios comprising the D10 signature (PARP9/PRDX2 and PLAC8/PRDX2) discriminate macaques that will progress to active tuberculosis (orange points) from macaques that will develop latent infection (blue points) using blood expression measurements made 10 days after challenge. The optimal decision boundary is indicated by dashed lines. Macaques with large values for both ratios are most likely to progress to active disease. Orange = progressors, blue = nonprogressors; circles = training set, triangles = test set. B, The mean (+/- 95% confidence interval) expression profile of PRDX2 after infection. Orange = progressors, blue = nonprogressors. C, PRDX2 is correlated to expression of erythrocyte genes in macaques after infection (Spearman ρ = .63; P < 10–15). Orange = progressors, blue = nonprogressors. D, PRDX2 is correlated to erythrocyte genes in humans from the human progressor dataset [9] during progression to tuberculosis disease (Spearman ρ = .67; P < 10–15). Orange = progressors, blue = nonprogressors. Expression of erythrocyte genes is computed from the average log2 expression levels of genes in the erythrocyte module that were correlated to PRDX2 (BSG, HMBS, RBM38, TESC, and UBE2O).

The day 10 signature involves 3 genes, 2 of which (PARP9 and PLAC8) are associated with interferon-driven responses and exhibit kinetic expression profiles that are similar to the reduced CoR (compare Supplementary Figure 3 with Figure 1C). On the other hand, the third gene in the day 10 signature, PRDX2, exhibits distinct expression response kinetics (Figure 2B), peaking early after infection (day 20) and exhibiting almost universally higher expression in controller macaques than in progressor macaques. To better understand the biological processes that may be represented by the PRDX2 expression pattern, we performed module enrichment analysis of genes that are strongly correlated with PRDX2 in macaques and humans (Supplementary Tables 15 and 16). Blood transcriptional modules for erythrocytes and heme metabolism were significantly overrepresented and strongly correlated with PRDX2 expression in both systems (Figure 2C and D), suggesting that PRDX2 may represent a readout for the health status of erythrocytes, with lower levels being associated with progression to active tuberculosis.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that a reduced, cross-species version of the blood RNA-based signature of risk for tuberculosis progression in humans [9] is predictive of progression to active tuberculosis in the cynomolgus macaque Mtb-challenge model at multiple time points months before the macaques are diagnosed with active disease. This result is important for 3 reasons: (1) it provides additional validation and refinement of the human signature; (2) it provides additional support for the veracity of the cynomolgus macaque model for Mtb infection, demonstrating that blood-based molecular readouts allow cross-species prediction; and (3) it demonstrates that inflammatory differences between animals that will progress to active tuberculosis and those that will develop latent infection are established very early after Mtb exposure. Despite the cross-species predictive capacity of the reduced CoR, the kinetics of tuberculosis disease progression in cynomolgus macaques after challenge occur rapidly, on a timescale of days. Contrastingly, the progression from latent infection to active tuberculosis that we observed in humans occurred on a timescale of months [9]. The rapid kinetics may partly explain some of the variability observed using the signatures in macaques that was less apparent in the human study [9]. Regardless of these differences, the reduced CoR remained robustly predictive of outcome.

To take further advantage of the cynomolgus macaque model for analyzing early inflammatory responses to Mtb challenge, we identified and validated a novel signature that predicts tuberculosis progression early (10 days) after challenge (Figure 2A, Supplementary Tables 8 and 14). This signature implicated a novel gene, PRDX2, which is upregulated early after infection and is preferentially expressed in controller macaques. PRDX2 is a member of the reactive oxygen species scavenger system and negatively regulates hypoxia-inducible factors during hypoxia [11], a physiologically relevant state in granulomas [12]. Furthermore, a protective role against tuberculosis in mice was shown for the related gene PRDX1 [13]. PRDX2 expression levels are strongly correlated with erythrocyte and heme metabolism modules, confirming previously identified association between PRDX2 and red blood cells [14, 15]. Taken together, these results demonstrate an association between increased expression of PRDX2 and more successful containment of tuberculosis infection, potentially through the mechanisms of increased protection of red blood cells from oxidative stress and inhibited hypoxic conditions. This result is consistent with the negative correlations observed between erythropoiesis gene modules and pulmonary inflammation (as measured by PET-CT FDG uptake) in a previous microarray-based analysis of the training set macaques from this study [10].

Although our analyses demonstrate the value of blood-based transcriptional signatures for predicting outcomes of Mtb infection in humans and macaques, further studies are necessary to determine the functions of the implicated genes in controlling Mtb and how the blood-based measurements relate to the highly heterogeneous inflammatory processes within the granulomas themselves.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (HL106804 and HL110811 to J. L. F.; AI 111871 to P. L. L.; and U19 AI106761 to A. A.) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1087783 to A. A. and D. E. Z. and other awards to P. L. L. and J. L. F.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Capuano SV 3rd, Croix DA, Pawar S et al. Experimental Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of cynomolgus macaques closely resembles the various manifestations of human M. tuberculosis infection. Infect Immun 2003; 71:5831–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin PL, Rodgers M, Smith L et al. Quantitative comparison of active and latent tuberculosis in the cynomolgus macaque model. Infect Immun 2009; 77:4631–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barry CE 3rd, Boshoff HI, Dartois V et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 2009; 7:845–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cadena AM, Flynn JL, Fortune SM. The importance of first impressions: early events in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection influence outcome. MBio 2016; 7:e00342–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lin PL, Flynn JL. Understanding latent tuberculosis: a moving target. J Immunol 2010; 185:15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berry MP, Graham CM, McNab FW et al. An interferon-inducible neutrophil-driven blood transcriptional signature in human tuberculosis. Nature 2010; 466:973–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bloom CI, Graham CM, Berry MP et al. Detectable changes in the blood transcriptome are present after two weeks of antituberculosis therapy. PLoS One 2012; 7:e46191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zak DE, Penn-Nicholson A, Scriba TJ et al. ; ACS and GC6-74 cohort study groups A blood RNA signature for tuberculosis disease risk: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 2016; 387:2312–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gideon HP, Skinner JA, Baldwin N, Flynn JL, Lin PL. Early whole blood transcriptional signatures are associated with severity of lung inflammation in cynomolgus macaques with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J Immunol 2016; 197:4817–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luo W, Chen I, Chen Y, Alkam D, Wang Y, Semenza GL. PRDX2 and PRDX4 are negative regulators of hypoxia-inducible factors under conditions of prolonged hypoxia. Oncotarget 2016; 7:6379–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Via LE, Lin PL, Ray SM et al. Tuberculous granulomas are hypoxic in guinea pigs, rabbits, and nonhuman primates. Infect Immun 2008; 76:2333–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matsumura K, Iwai H, Kato-Miyazawa M et al. Peroxiredoxin 1 contributes to host defenses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol 2016; 197:3233–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Franceschi L, Bertoldi M, De Falco L et al. Oxidative stress modulates heme synthesis and induces peroxiredoxin-2 as a novel cytoprotective response in β-thalassemic erythropoiesis. Haematologica 2011; 96:1595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nagababu E, Mohanty JG, Friedman JS, Rifkind JM. Role of peroxiredoxin-2 in protecting RBCs from hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress. Free Radic Res 2013; 47:164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.