We provide a comprehensive and timely review on the molecular and genetic mechanisms of fertilization-independent fruit development, a topic of major scientific and agricultural importance.

Keywords: Auxin, fruit set, gibberellins, MADS-box, parthenocarpy, seedless fruit

Abstract

Fruit set—the commitment of an angiosperm plant to develop fruit—is a key developmental process that normally occurs following successful fertilization. Parthenocarpy arises when fruit automatically develop in the absence of fertilization. This review uses parthenocarpic fruit development as a focal device through which to recapitulate and understand the molecular effectors that mediate and regulate fruit set. The review demonstrates that studies of parthenocarpy are providing vital insight into plant development, signaling and, potentially, high-value agricultural products.

Overview

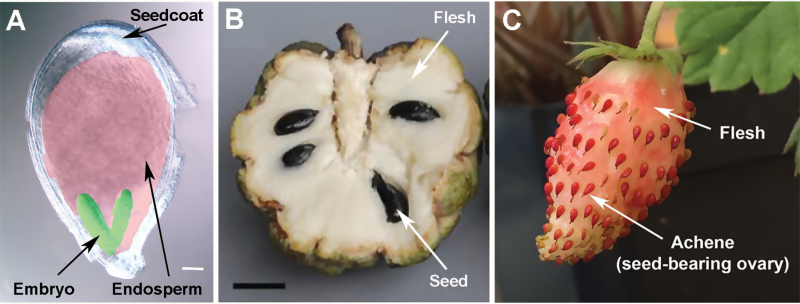

In flowering plants, two distinct but parallel fertilization events are ordinarily necessary for the development of the seed and any subsequent fruit tissues. Fertilization of the egg cell results in the development of an embryo, the progenitor of the successor sporophyte plant. The second male gamete fertilizes the heretofore diploid central cell of the female gametophyte, which leads to the development of the endosperm, a triploid, placenta-like nutritive tissue vital to the survival of the embryo (Box 1; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Illustration of botanical and accessory fruits and seed composition. (A) An image of a strawberry seed illustrating the maternal diploid seed coat, triploid endosperm (false-color pink) and the diploid embryo (false-color green). Scale bar=100 μm. (B) An example of a botanical fruit. Seeds are embedded in the fruit flesh derived from the ovary wall of Annona squamosa (the sugar apple). The image is from Lora et al. (2011). (C) An example of an accessory fruit in Fragaria vesca (the wild strawberry). The fruit flesh is derived from the receptacle (stem tip) of a flower. The botanical fruit (achene) dots the surface of the receptacle.

In most instances, this double fertilization is required for proper seed and fruit development (Dumas and Rogowsky, 2008), and early experiments in strawberry (Fragaria×ananassa) have shown that the removal of the fertilized seed suppressed further development of fruit (Nitsch, 1950). ‘Fruit set’ (Box 1) is the initiation of the developmental program that leads to the fruit; it depends on successful fertilization in most cases. Following fertilization, specific floral tissue(s) would enlarge and develop into structures which protect and facilitate dispersal of the fertile seeds (Sotelo-Silveira et al., 2014). These protective structures, fleshy or dry, are typically derived from the ovary wall leading to the ‘botanical fruit’ as in tomato, Annona (sugar apple), and Prunus persica (peach) (Box 1; Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, the fruit flesh in some plants is derived from non-ovary tissues, and hence the ‘accessory fruit’ such as strawberry and apple (Box 1; Fig. 1C).

Box 1. Key terms and definitions

Double fertilization: the complex union of male and female gametes in flowering plants. Two sperm within a single pollen tube enter the female gametophyte; one sperm fuses with the egg cell to form a zygote while the second sperm fertilizes the diploid central cell to form the endosperm.

Endosperm: triploid tissue inside the seed providing nutrition to the embryo. It is derived from fertilization of the diploid central cell of the female gametophyte. It is an important source of starch and oils in human diet.

Fruit set: the initiation or commitment to initiate fruit development, which includes the swelling of ovary, the botanical fruit, or the swelling of other floral parts such as the receptacle in the case of accessory (atypical) fruit.

Parthenocarpy: fruit formation, in whole or in part, without fertilization or pollination.

Apomixis: reproduction of organisms without fertilization. The embryo is produced from diploid maternal tissues in the absence of meiosis.

Stenospermocarpy: the production of abortive, incompletely developed seeds (as in a seedless grape) with normal development of the berry (Merriam-Webster, 2003).

Botanical fruit: the seed-bearing structure derived from the ovary wall of the flowering plant. Examples are tomato, plum, and bean pods.

Accessory fruit: atypical fruit. The fruit flesh is derived from non-ovary tissues such as the receptacle in strawberry and the hypanthium in apple.

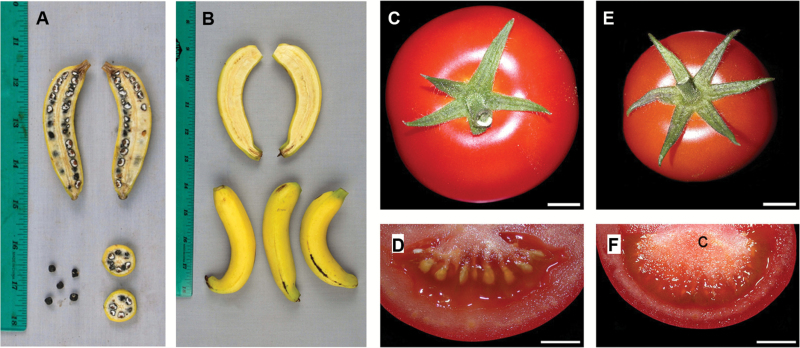

Some plants, however, supersede the requirement for fertilization. This ability is known as ‘parthenocarpy’ (Box 1), which arises from Greek words for ‘virgin fruit’. Parthenocarpy has contributed to perhaps some of humanity’s oldest domestic crops: it appears to have figured prominently in the domestication of breadfruit, banana, and fig (Fig. 2A, B) (Zerega et al., 2004; Kislev et al., 2006; Sardos et al., 2016). That some plants may produce fruit without the need for fertilization by the male gamete raises an important question of basic science—how do such plants trigger a profound development program without the biochemical contribution normally required from sperm? It also raises critical technological questions, as parthenocarpy supplies several direct and practical benefits.

Fig. 2.

Photos of parthenocarpic fruits in comparison with fertilized fruits. (A) Fruits of wild and seeded banana (Musa acuminata banksia). (B) Domesticated parthenocarpic banana fruit. (C) A fertilization-induced tomato fruit of the Monalbo variety. (D) The ‘Monalbo’ wild-type fruit cut in half. The locule is filled with pulp and the seed are clearly visible. (E) A parthenocarpic fruit from ‘Monalbo’ containing the abnormal arf8 mutant transgene. (F) The same parthenocarpic fruit in (E) cut in half. The central columella (c) is enlarged and the locule is filled with pulp, showing a seedless endocarp. Scale bars=1 cm in (C–F). Images (A) and (B) are from Sardos et al. (2016) under Creative Commons Attribution License; images in (C)–(F) are from Goetz M, Hooper LC, Johnson SD, Rodrigues JC, Vivian-Smith A, Koltunow AM. 2007. Expression of aberrant forms of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 stimulates parthenocarpy in Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant Physiology 145, 351–366, with permission (Copyright American Society of Plant Biologists).

Progress has been made across several plant species toward an understanding of the mysteries of virgin fruit. Classic scientific experiments demonstrated that phytohormones can induce parthenocarpy; more recent research has uncovered the molecular mechanisms through which these phytohormones achieved such effects. Table 1 provides a summary list of genes and phytohormones previously linked to parthenocarpy. The bulk of the review will focus on the progress made toward identifying gene products that guide fruit development—genes that act as producers and perceivers of signals—and how changes to these signals and signal sensors have led to parthenocarpy. This review argues that recent genetic advances in model systems, particularly in Arabidopsis thaliana and tomato, have left the field well positioned for much deeper research into plants of greater agricultural significance. That transition has begun; much work remains before us.

Table 1.

Genes and phytohormones involved in parthenocarpic fruit development

| Target | Cause/treatment | Underlying pathway | Species | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Auxin (naphthoxyacetic acid) | Exogenous application | Auxin | Strawberry (Fragaria ananassa and F. vesca) | Nitsch (1950); Kang et al. (2013) |

| YUCCA | Overexpression | Auxin | Eriobotrya japonica | Mesejo et al. (2010) |

| ARF-7/8 | Underexpression | Auxin | A. thaliana; S. lycopersicum | Goetz et al. (2007); de Jong et al. (2009b) |

| IAA | Differential expression found in natural parthenocarpic mutant | Auxin | S. melongena | Chen et al. (2017) |

| AUCSIA | RNAi | Auxin | S. lycopersicum | Molesini et al. (2009) |

| PIN-4 | RNAi | Auxin | S. lycopersicum | (Mounet et al., 2012) |

| Gibberellic acid | Exogenous application | GA | R. rugosa; M. domestica; F. vesa | Davison (1960); Prosser and Jackson (1959); Kang et al. (2013) |

| GA20OX | Overexpression | GA | A. thaliana; S. lycopersicum | García-Hurtado et al. (2012) |

| DELLA | RNAi; loss-of-function mutations | GA | A. thaliana; S. lycopersicum | Martí et al. (2007); Fuentes et al. (2012) |

| Cytokinin | Exogenous application | Cytokinin | C. lanatus; A. deliciosa | Hayata and Niimi (1995); Lewis et al. (1996) |

| MET1 | RNAi | DNA methylation | A. thaliana | FitzGerald et al. (2008); Schmidt et al. (2013) |

| MEDEA | Loss-of-function mutation | PRC2 histone methylation | A. thaliana | Köhler et al. (2003) |

| FIS2 | Loss-of-function mutation | PRC2 histone methylation | A. thaliana | Chaudhury et al. (1997) |

| FIE | Loss-of-function mutation | PRC2 histone methylation | A. thaliana | Ohad et al. (1996) |

| MSI | Loss-of-function mutation | PRC2 histone methylation | A. thaliana | Guitton and Berger (2005) |

| PISTILLATA | Gain- and loss-of-function mutations | MADS-box | Malus domesticus; Vinis vinifera | Yao et al. (2001); Fernandez et al. (2013) |

| DEFICIENS | Loss-of-function mutation | MADS-box | Elaeis guineensis | Ong-Abdullah et al. (2015) |

| SEP1/TM29 | Antisense or co-suppression | MADS-box | S. lycopersicum | Ampomah-Dwamena et al. (2002) |

This review will not, however, seek to encompass some subjects closely related to parthenocarpy. It will not cover apomixis (Box 1), which is also asexual reproduction, but which results in the development of an embryo from unreduced female tissue. The review also will not cover stenospermocarpy (Box 1)—seedlessness or near seedlessness—caused by the spontaneous or induced abortion of a fertilized seed; this process’s dependence on fertilization distinguishes it from parthenocarpy, which has no requirement for sperm or fertilization at any point.

Indeed, the distinction between parthenocarpy and stenospermocarpy underscores some of the key benefits of parthenocarpy (Ruan et al., 2012). First, pollination can be costly, can require specific pollinators, and generally demands specific temperature and other ambient conditions. All of these requirements are threatened by climate change, disease, or other phenomena. Secondly, parthenocarpic fruit is seedless fruit, which is preferred by many consumers, and requires less processing in many agricultural applications. Thirdly, parthenocarpy results in precocious development of the endosperm, which is the principal source of nutritional and agricultural value in many plants. Finally, parthenocarpy provides insight into the mechanisms governing endosperm development and fruit set.

Because of its diverse origins, studies of parthenocarpy have encompassed a wide range of subjects in plant signaling and development, and continued study also should allow practically oriented, fundamental research science. This review begins with discussion of phytohormones in fertilization-induced fruit development, highlights emerging insights into epigenetic regulation of fertilization, and underscores the importance of MADS-box transcription factors. It concludes with final thoughts on major opportunities lying ahead for this exciting field of research.

The role of hormones in parthenocarpy

The earliest observations of parthenocarpy involved natural mutations. Insight into molecular explanations of parthenocarpy began with the study of the role of phytohormones. Auxin was the phytohormone first identified as capable of inducing parthenocarpic fruit development, in citrus and later in strawberry (Gustafson, 1939; Nitsch, 1950). These experiments showed that ovaries generate auxin signals that induce development of both botanical and accessory fruits, and that ectopic supply of auxin-like substances would have similar effects. Gibberellic acid (GA) later was shown to have a similar effect on roses and apples (Prosser and Jackson, 1959; Davison, 1960). Much later, ectopic cytokinins were shown to induce parthenocarpy in watermelon and kiwifruit (Hayata and Niimi, 1995). In contrast to the potential of auxins or GA to induce parthenocarpy, abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene signals have not been shown to be positively related to parthenocarpy. Indeed, ABA levels are low in the ovaries of parthenocarpic mandarin oranges (Mesejo et al., 2010), and ethylene has been shown to suppress fruit set in tomato (Shinozaki et al., 2015).

These early insights into the role of phytohormones led to a wave of discoveries related to the pathways necessary to metabolize and sense these hormones. Focusing particularly on auxin and GA, where the bulk of research has been done, parthenocarpic mutations were found in a variety of species. Research into cytokinin-related parthenocarpy is less advanced at present.

Auxin-related parthenocarpy has been found in a number of steps within the auxin synthesis, perception, and signaling pathways. Transgenic eggplants (Solanum melongena) and tobacco showed enlarged and parthenocarpic fruits due to the ovule-specific expression of an auxin biosynthesis gene DefH9::iaaM (Rotino et al., 1997). Overexpression of the auxin receptor TIR1 in tomato gives a parthenocarpic phenotype (Ren et al., 2011). Similarly, the suppression of auxin signal repressors is associated with parthenocarpy. For instance, a loss or reduction of function in the tomato IAA9 gene resulted in parthenocarpic seedless tomato fruit (Wang et al., 2005; Mazzucato et al., 2015), and in eggplant, RNA-seq data also link reduced expression of indole acetic acid (IAA) repressor genes with parthenocarpic fruit development (Chen et al., 2017). Similarly, removing the function of negative regulators of auxin signaling encoded by AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR 8 (AtARF8) in A. thaliana and tomato and ARF7 in tomato also led to fertilization-independent fruit development (Goetz et al., 2006, 2007; de Jong et al., 2009b) (Fig. 2C–F). In another example, RNAi silencing of the AUCSIA genes encoding plant peptides that restrain auxin response was shown to lead to parthenocarpic fruit development (Molesini et al., 2009). Together, these experiments reinforce classic auxin experiments, providing molecular-level evidence that auxin biosynthesis and signaling regulate fruit set and that constitutive auxin signaling could lead to parthenocarpic fruit. Auxin appears to be an essential signal that relieves the typical repression of a fruit set program.

Changes in the GA signaling pathways also have been shown to induce parthenocarpic fruit set and fruit development. After the early findings that ectopic application of GA to rose and apple flowers and ovaries led to fruit set, later experiments in manually deseeded or emasculated strawberries showed that the application of GA could still induce enlargement of the fruit-like receptacle tissue, even in the absence of pollination (Thompson, 1969; Kang et al., 2013). In the heavily studied pat varieties of parthenocarpic tomatoes, aberrant expression of the GA pathway is a consistent characteristic (de Jong et al., 2009a), with GA20, the GA precursor, accumulating at higher levels in unfertilized ovaries than in wild-type counterparts (Fos et al., 2000; Olimpieri et al., 2007). Overexpression and ectopic expression of gibberellin 20-oxidase—the enzyme that completes the final metabolic step in production of bioactive GA—leads to production of parthenocarpic fruit in tomato and in Arabidopsis (García-Hurtado et al., 2012). The key repressor of GA signal transduction is the DELLA protein, and, concomitantly, reduction in DELLA activity has been shown to lead to constitutive GA signaling phenotypes that have included parthenocarpic fruit development. For instance, reduced DELLA activity in the procera loss-of-function mutation or via RNAi has led to unfertilized fruit set in tomato and silique development in Arabidopsis (Martí et al., 2007; Bassel et al., 2008; Fuentes et al., 2012). Parthenocarpy in the Arabidopsis della mutant led to siliques that are shorter than normal; the addition of auxin corrects this deficiency. However, this corrective effect of auxin was lost when GA synthesis was blocked by mutations, suggesting that the auxin input is upstream of GA biosynthesis (Fuentes et al., 2012). This crosstalk between auxin and GA signaling pathways has also been found in tomato (Serrani et al., 2008; Ding et al., 2013).

Cytokinins also have induced parthenocarpic fruit development in species including watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), Japanese pears (Pyrus pyrifolia), and kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) (Hayata and Niimi, 1995; Lewis et al., 1996; Kadota and Niimi, 2003). Cytokinin’s two-component signal transduction pathway is quite different from that of auxin or GA. Instead, the signal is relayed by a series of phosphorylation events transferred to effector proteins and eventually genes (Stock et al., 2000). As such, constitutively active cytokinin signal transduction components—rather than knockouts of negative regulators—are the most likely genetic source of parthenocarpy. To date, however, very little research has been conducted on such plants with such mutations; this may represent an important research opportunity.

Hormone transport should play a key role in fruit set, as the phytohormone-producing tissue, the seed, is spatially situated next to, on top, or beneath the phytohormone-sensing fruit tissues. RNAi knockdown of an ovary-specific auxin efflux transport protein has been shown to lead to production of parthenocarpic fruit in tomato (Mounet et al., 2012), perhaps reflecting an accumulation of excess auxin in the ovary. Transcriptome-level research in strawberry and tissue-specific expression of a dominant negative IAA allele in Arabidopsis show that auxin generated in the endosperm within a seed initiates fruit set and the effect of auxin on fruit set relies on proper transport from the site of synthesis to the target fruit tissue (Kang et al., 2013; Figueiredo et al., 2015). These studies highlight the endosperm within the seed as the source of auxin.

To summarize, a number of phytohormones have been shown to induce parthenocarpic fruit development in a number of plant species. Similarly, changes in the synthesis and metabolism of hormones or components within the signaling pathway may also induce fruit development in the absence of fertilization. Very broadly, this research emphasizes that changes to a plant’s ability to generate and perceive the ‘fruit set program’ signal are central to potential parthenocarpy.

Epigenetic mechanisms in fruit set

The critical role of epigenetic mechanisms in regulating complex development programs and tissue differentiation has long been appreciated (Allis and Jenuwein, 2016), and the importance of such mechanisms is arguably elevated further in plants than in motile animals. As such, it is not surprising that epigenetic mechanisms appear to play a key role in fruit development. Epigenetic regulation occurs at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional time points and at three distinct levels: at chromatin, DNA, and mRNA. This review argues that regulation or disturbance at each level can contribute to fertilized or parthenocarpic fruit set, respectively.

Two major mechanisms of transcriptional regulation are via histone modifications in chromatin and the methylation of cytosine in the underlying DNA strands. In seeds and fruit, the major mechanism responsible for histone modification is the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2), and the predominant mechanism regulating DNA methylation is RNA-directed DNA methylation (Gehring and Satyaki, 2017). DNA methylation, in which a methyl group is attached to the fifth carbon of cytosine residues within a DNA transcript, generally leads to reduced expression of a gene. In Arabidopsis, DRM2 acts as the major de novo methyltransferase enzyme and is largely regulated by RNA-directed DNA methylation (Stroud et al., 2012; Borges and Martienssen, 2015). MET1 and CMT3 are the primary maintenance methyltrasferases, responsible for reproducing DNA methylation during DNA replication (Bartee et al., 2001; Kankel et al., 2003). Together, these systems of methylation provide exquisite, gene-level transcriptional control, and are critical to establishing the fates of differentiated tissues.

Operating at the genomic level, PRC2, which is conserved across fungi, animals, and plants (Lewis, 2017), adds repressive modifications to amino acid residues on the ‘tails’ of nucleosome histones. Products of several genes together comprise the Arabidopsis PRC2; most prominent in the fate of the seed are a group that contribute to the ‘FIS’, or Fertilization Independent Seed, version of the complex (Hands et al., 2016). These genes consist of MEDEA (MEA), a homolog of the Drosophila melanogaster gene Enhancer of Zeste; FERTILIZATION INDEPENDENT SEED 2 (FIS2), a homolog of the Drosophila gene Suppressor of Zeste; FERTILIZATION INDEPENDENT ENDOSPERM (FIE), homologous to the Drosophila Extra sex combs; and MULTICOPY SUPRESSOR OF IRA1 (MSI1), homologous to p55 in Drosophila (Ohad et al., 1996; Chaudhury et al., 1997; Köhler et al., 2003; Guitton and Berger, 2005).

Perturbation in DNA methylation and the function of PRC2 have been shown to contribute toward parthenocarpic phenotypes. met1 plants have precocious and overproliferative integuments surrounding the female gamete (FitzGerald et al., 2008). Arabidopsis mutants defective in the PRC2-component genes have been linked to fertilization-independent seed development and precocious development of the silique fruit tissues in Arabidopsis (Chaudhury et al., 1997; Goodrich et al., 1997). This fertilization-independent seed development, however, does not lead to a fully viable seed but rather to a relatively early abortion of seed development mediated by a mechanism of programmed cell death (Chaudhury et al., 1997). Arabidopsis heterozygous for a knock down allele of Met1 and MEA are substantially more likely to cause fertilization-independent endosperm development than the mea-only heterozygote (Schmidt et al., 2013), demonstrating linkage between the two epigenetic pathways and reinforcing the role of DNA methylation in preserving the seed ‘state’ (unfortunately, the study did not indicate whether met1/mea mutants also demonstrated the fertilization-independent silique elongation phenotype). Nonetheless, despite the pronounced phenotype found in Arabidopsis, inactivation of PRC2 component homologs in other plants does not have demonstrated parthenocarpic effects. This may be due to redundancy in these genes in other species. Nevertheless, research on FIS-type genes in other plants remains active (Luo et al., 2009; Nallamilli et al., 2013; Boureau et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016).

In Arabidopsis, it was found that the PRC2 complex represses AGAMOUS-LIKE 62 (AGL62), which encodes a MADS-box transcription factor and acts to prevent premature cellularization in the endosperm tissue (Kang et al., 2008). Upon fertilization, AGL62 is expressed in the Arabidopsis endosperm and promotes the transport of auxin to the seed coat for proper seed coat development (Figueiredo et al., 2015, 2016). Loss of the PRC2 complex allows the continued expression of AGL62 in the central cell, thereby leading to automatic endosperm development (Kang et al., 2008). Although much remains unknown regarding the mechanism of epigenetic regulation during seed set and fruit set, fertilization-induced de-repression may underlie the fertilization-induced signal production and transduction for both seed set and fruit set.

Certain MADS-box genes encode repressors of fruit development

It has been appreciated for many years that, early in the flower development process, mutations in the gene PISTILLATA (PI), a MADS-box transcription factor and a B class gene, controls petal and stamen floral organ identity in Arabidopsis (Goto and Meyerowitz, 1994). This homeotic gene, however, appears to have broader functions in other species. In apple (Malus domestica), two cultivars sharing similar retrotransposon-mediated splicing variants of the AtPI homolog produced parthenocarpic fruit as well as mutant floral morphology that closely resembled that of the Arabidopsis pi loss-of-function mutants (Yao et al., 2001). Constitutive overexpression—also conferred by transposon insertion—of a PI homolog in grape (Vinis vinifera) blocked fruit set despite pollination (Fernandez et al., 2013). DEFICIENS (DEF), like PI, is a B class MADS-box gene regulating petal/stamen identity in snapdragon (Sommer et al., 1990). In oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), hypomethylation of a retrotransposon leads to alternative splicing of the oil palm homolog to DEF, which in turn produces aberrant floral structures and parthenocarpic fruit development (Ong-Abdullah et al., 2015). In tomato, deficiencies in expression of stamenless, a DEF homolog, lead to development of ovule tissue and occasional parthenocarpy (Mazzucato et al., 2008). The E-class floral homeotic genes also encode MADS-box proteins, which form complexes with B and C class genes (Pelaz et al., 2000; Honma and Goto, 2001). Consequently, reduced expression in the tomato E-class gene TM29 also led to parthenocarpic fruit development reminiscent of the B-class mutants (Ampomah-Dwamena et al., 2002). Together, these results suggest that B- and E-class MADS-box proteins may play a negative regulatory role in fleshy fruit development. When it is inactivated, fruit will automatically develop in the absence of fertilization. The study also pointed to a potential link between floral organ identity and fruit development.

Other MADS genes also regulate parthenocarpy. Recently, a parthenocarpic tomato mutant was identified in a clever mutagenesis screen for fruit-bearing tomato plants under extreme heat conditions that ensured pollen were no longer fertile. The mutant was found to be defective in the SlAGL6 gene, and CRISPR/CaS9 (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) gene knock down of SlAGL6 confirmed the phenotype (Klap et al., 2017). The work on B- and E-class floral homeotic genes and AGL6 indicates that certain MADS-box genes encode repressors of fruit development.

Conclusions and future directions

This review summarized several molecular mechanisms involved in parthenocarpic fruit set. Following early agricultural observations and scientific results, it has been shown that fruit set is a response to fertilization-induced phytohormone surge and transport. That changes to the synthesis and degradation of such hormones or perturbations of a plant’s ability to perceive such hormonal signals might also induce parthenocarpic fruit development is a logical outgrowth of those initial findings. As scientific understanding of the mechanisms has grown, significant progress has been made in understanding the mechanisms of parthenocarpy. Many such alterations have been uncovered across a wide variety of model and non-model systems. The relationship between auxin signaling and parthenocarpic fruit set was uncovered first, and knowledge of parthenocarpy-inducing modifications to this pathway are most advanced; opportunities remain to exploit the relationship of GA and especially cytokinin signaling pathways to parthenocarpy.

Epigenetics provides governing mechanisms for fertilization-mediated release of phytohormone signals. DNA methylation, reinforced by PRC2-mediated histone alterations, has been shown to contribute to the activation of endosperm and fruit development, and alterations in this regulatory relationship lead to fertilization-independent development. MADS-box genes appear to be a key link between floral development, fruit set, and parthenocarpy. While past research has uncovered these multiple, complex factors, we know from the earliest studies of angiosperms that fertilization is the central signal. It is therefore very possible, and indeed logical, to postulate that endosperm development and fruit set are linked to the same ultimate fertilization signal or master regulator, although the molecular basis of that cascade of signals remains to be discovered.

Research into parthenocarpy is directly relevant to a number of pressing agricultural concerns. It also provides a precise lens into the molecular mechanism of fertilization—a process incompletely understood in both plant and animal systems. The key messages of this review are that substantial progress has been made in answering the elegant, elusive questions surrounding a fruit’s virgin birth, and that significant opportunities remain for future work. Scientists, equipped with a significant knowledge base and new technology such as the CRISPR/CAS9 technology, are poised to improve agricultural productivity through parthenocarpy. Scientific prospects of this field are rather exciting.

Acknowledgements

The research in the laboratory of ZL is supported by National Science Foundation grant (IOS1444987). DJ is supported by a University of Maryland CMNS Dean’s Matching Award that is associated with the NIH T32 Molecular and Cell Biology Training Grant.

References

- Allis CD, Jenuwein T. 2016. The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nature Reviews. Genetics 17, 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ampomah-Dwamena C, Morris BA, Sutherland P, Veit B, Yao JL. 2002. Down-regulation of TM29, a tomato SEPALLATA homolog, causes parthenocarpic fruit development and floral reversion. Plant Physiology 130, 605–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartee L, Malagnac F, Bender J. 2001. Arabidopsis cmt3 chromomethylase mutations block non-CG methylation and silencing of an endogenous gene. Genes and Development 15, 1753–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassel GW, Mullen RT, Bewley JD. 2008. Procera is a putative DELLA mutant in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum): effects on the seed and vegetative plant. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges F, Martienssen RA. 2015. The expanding world of small RNAs in plants. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 16, 727–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boureau L, How-Kit A, Teyssier E et al. 2016. A CURLY LEAF homologue controls both vegetative and reproductive development of tomato plants. Plant Molecular Biology 90, 485–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury AM, Ming L, Miller C, Craig S, Dennis ES, Peacock WJ. 1997. Fertilization-independent seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 94, 4223–4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhang M, Tan J, Huang S, Wang C, Zhang H, Tan T. 2017. Comparative transcriptome analysis provides insights into molecular mechanisms for parthenocarpic fruit development in eggplant (Solanum melongena L.). PLoS One 12, e0179491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison RM. 1960. Fruit-setting of apples using gibberellic acid. Nature 188, 681–682. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M, Mariani C, Vriezen WH. 2009a The role of auxin and gibberellin in tomato fruit set. Journal of Experimental Botany 60, 1523–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong M, Wolters-Arts M, Feron R, Mariani C, Vriezen WH. 2009b The Solanum lycopersicum auxin response factor 7 (SlARF7) regulates auxin signaling during tomato fruit set and development. The Plant Journal 57, 160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Chen B, Xia X, Mao W, Shi K, Zhou Y, Yu J. 2013. Cytokinin-induced parthenocarpic fruit development in tomato is partly dependent on enhanced gibberellin and auxin biosynthesis. PLoS One 8, e70080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas C, Rogowsky P. 2008. Fertilization and early seed formation. Comptes Rendus Biologies 331, 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez L, Chaïb J, Martinez-Zapater JM, Thomas MR, Torregrosa L. 2013. Mis-expression of a PISTILLATA-like MADS box gene prevents fruit development in grapevine. The Plant Journal 73, 918–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo DD, Batista RA, Roszak PJ, Hennig L, Köhler C. 2016. Auxin production in the endosperm drives seed coat development in Arabidopsis. eLife 5, e20542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo DD, Batista RA, Roszak PJ, Köhler C. 2015. Auxin production couples endosperm development to fertilization. Nature Plants 1, 15184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald J, Luo M, Chaudhury A, Berger F. 2008. DNA methylation causes predominant maternal controls of plant embryo growth. PLoS One 3, e2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fos M, Nuez F, García-Martínez JL. 2000. The gene pat-2, which induces natural parthenocarpy, alters the gibberellin content in unpollinated tomato ovaries. Plant Physiology 122, 471–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes S, Ljung K, Sorefan K, Alvey E, Harberd NP, Østergaard L. 2012. Fruit growth in Arabidopsis occurs via DELLA-dependent and DELLA-independent gibberellin responses. The Plant Cell 24, 3982–3996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Hurtado N, Carrera E, Ruiz-Rivero O, López-Gresa MP, Hedden P, Gong F, García-Martínez JL. 2012. The characterization of transgenic tomato overexpressing gibberellin 20-oxidase reveals induction of parthenocarpic fruit growth, higher yield, and alteration of the gibberellin biosynthetic pathway. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 5803–5813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring M, Satyaki PR. 2017. Endosperm and imprinting, inextricably linked. Plant Physiology 173, 143–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M, Hooper LC, Johnson SD, Rodrigues JC, Vivian-Smith A, Koltunow AM. 2007. Expression of aberrant forms of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 stimulates parthenocarpy in Arabidopsis and tomato. Plant Physiology 145, 351–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetz M, Vivian-Smith A, Johnson SD, Koltunow AM. 2006. AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 is a negative regulator of fruit initiation in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 18, 1873–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich J, Puangsomlee P, Martin M, Long D, Meyerowitz EM, Coupland G. 1997. A Polycomb-group gene regulates homeotic gene expression in Arabidopsis. Nature 386, 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto K, Meyerowitz EM. 1994. Function and regulation of the Arabidopsis floral homeotic gene PISTILLATA. Genes and Development 8, 1548–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guitton AE, Berger F. 2005. Loss of function of MULTICOPY SUPPRESSOR OF IRA 1 produces nonviable parthenogenetic embryos in Arabidopsis. Current Biology 15, 750–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson FG. 1939. Auxin distribution in fruits and its significance in fruit development. American Journal of Botany 26, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Hands P, Rabiger DS, Koltunow A. 2016. Mechanisms of endosperm initiation. Plant Reproduction 29, 215–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayata Y, Niimi Y. 1995. Synthetic cytokinin-1-(2=chloro=4=pyridyl)-3-phenylurea (CPPU)-promotes fruit set and induces parthenocarpy in watermelon. Journal of the American Horticultural Society 120, 997–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Honma T, Goto K. 2001. Complexes of MADS-box proteins are sufficient to convert leaves into floral organs. Nature 409, 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadota M, Niimi Y. 2003. Effects of cytokinin types and their concentrations on shoot proliferation and hyperhydricity in in vitro pear cultivar shoots. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 72, 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kang C, Darwish O, Geretz A, Shahan R, Alkharouf N, Liu Z. 2013. Genome-scale transcriptomic insights into early-stage fruit development in woodland strawberry Fragaria vesca. The Plant Cell 25, 1960–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang IH, Steffen JG, Portereiko MF, Lloyd A, Drews GN. 2008. The AGL62 MADS domain protein regulates cellularization during endosperm development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 20, 635–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kankel MW, Ramsey DE, Stokes TL, Flowers SK, Haag JR, Jeddeloh JA, Riddle NC, Verbsky ML, Richards EJ. 2003. Arabidopsis MET1 cytosine methyltransferase mutants. Genetics 163, 1109–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kislev ME, Hartmann A, Bar-Yosef O. 2006. Early domesticated fig in the Jordan Valley. Science 312, 1372–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klap C, Yeshayahou E, Bolger AM, Arazi T, Gupta SK, Shabtai S, Usadel B, Salts Y, Barg R. 2017. Tomato facultative parthenocarpy results from SlAGAMOUS-LIKE 6 loss of function. Plant Biotechnology Journal 15, 634–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhler C, Hennig L, Spillane C, Pien S, Gruissem W, Grossniklaus U. 2003. The Polycomb-group protein MEDEA regulates seed development by controlling expression of the MADS-box gene PHERES1. Genes and Development 17, 1540–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis ZA. 2017. Polycomb group systems in fungi: new models for understanding polycomb repressive complex 2. Trends in Genetics 33, 220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis DH, Burge GK, Hopping ME, Jameson PE. 1996. Cytokinins and fruit development in the kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa). II. Effects of reduced pollination and CPPU application. Physiologia Plantarum 98, 187–195. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Xu T, Dong X, Liu Y, Liu Z, Shi Z, Wang Y, Qi M, Li T. 2016. The role of gibberellins and auxin on the tomato cell layers in pericarp via the expression of ARFs regulated by miRNAs in fruit set. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum 38, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Lora J, Hormaza JI, Herrero M, Gasser CS. 2011. Seedless fruits and the disruption of a conserved genetic pathway in angiosperm ovule development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 108, 5461–5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M, Platten D, Chaudhury A, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES. 2009. Expression, imprinting, and evolution of rice homologs of the polycomb group genes. Molecular Plant 2, 711–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martí C, Orzáez D, Ellul P, Moreno V, Carbonell J, Granell A. 2007. Silencing of DELLA induces facultative parthenocarpy in tomato fruits. The Plant Journal 52, 865–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato A, Cellini F, Bouzayen M, Zouine M, Mila I, Minoia S, Petrozza A, Picarella ME, Ruiu F, Carriero F. 2015. A TILLING allele of the tomato Aux/IAA9 gene offers new insights into fruit set mechanisms and perspectives for breeding seedless tomatoes. Molecular Breeding 35, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato A, Olimpieri I, Siligato F, Picarella ME, Soressi GP. 2008. Characterization of genes controlling stamen identity and development in a parthenocarpic tomato mutant indicates a role for the DEFICIENS ortholog in the control of fruit set. Physiologia Plantarum 132, 526–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster 2003. Merriam-Webster’s collegiate dictionary. Springfield, OH: Merriam Webster. [Google Scholar]

- Mesejo C, Reig C, Martínez-Fuentes A, Agustí M. 2010. Parthenocarpic fruit production in loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) by using gibberellic acid. Scientia Horticulturae 126, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Molesini B, Pandolfini T, Rotino GL, Dani V, Spena A. 2009. Aucsia gene silencing causes parthenocarpic fruit development in tomato. Plant Physiology 149, 534–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounet F, Moing A, Kowalczyk M et al. 2012. Down-regulation of a single auxin efflux transport protein in tomato induces precocious fruit development. Journal of Experimental Botany 63, 4901–4917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nallamilli BR, Zhang J, Mujahid H, Malone BM, Bridges SM, Peng Z. 2013. Polycomb group gene OsFIE2 regulates rice (Oryza sativa) seed development and grain filling via a mechanism distinct from Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics 9, e1003322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch JP. 1950. Growth and morphogenesis of the strawberry as related to auxin. American Journal of Botany 37, 211–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ohad N, Margossian L, Hsu YC, Williams C, Repetti P, Fischer RL. 1996. A mutation that allows endosperm development without fertilization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 93, 5319–5324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olimpieri I, Siligato F, Caccia R, Mariotti L, Ceccarelli N, Soressi GP, Mazzucato A. 2007. Tomato fruit set driven by pollination or by the parthenocarpic fruit allele are mediated by transcriptionally regulated gibberellin biosynthesis. Planta 226, 877–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong-Abdullah M, Ordway JM, Jiang N et al. 2015. Loss of Karma transposon methylation underlies the mantled somaclonal variant of oil palm. Nature 525, 533–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelaz S, Ditta GS, Baumann E, Wisman E, Yanofsky MF. 2000. B and C floral organ identity functions require SEPALLATA MADS-box genes. Nature 405, 200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser MV, Jackson GAD. 1959. Induction of parthenocarpy in Rosa arvensis huds. with gibberellic acid. Nature 184, 108. [Google Scholar]

- Ren Z, Li Z, Miao Q, Yang Y, Deng W, Hao Y. 2011. The auxin receptor homologue in Solanum lycopersicum stimulates tomato fruit set and leaf morphogenesis. Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 2815–2826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotino GL, Perri E, Zottini M, Sommer H, Spena A. 1997. Genetic engineering of parthenocarpic plants. Nature Biotechnology 15, 1398–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan YL, Patrick JW, Bouzayen M, Osorio S, Fernie AR. 2012. Molecular regulation of seed and fruit set. Trends in Plant Science 17, 656–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardos J, Rouard M, Hueber Y, Cenci A, Hyma KE, van den Houwe I, Hribova E, Courtois B, Roux N. 2016. A genome-wide association study on the seedless phenotype in banana (Musa spp.) reveals the potential of a selected panel to detect candidate genes in a vegetatively propagated crop. PLoS One 11, e0154448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt A, Wöhrmann HJ, Raissig MT, Arand J, Gheyselinck J, Gagliardini V, Heichinger C, Walter J, Grossniklaus U. 2013. The Polycomb group protein MEDEA and the DNA methyltransferase MET1 interact to repress autonomous endosperm development in Arabidopsis. The Plant Journal 73, 776–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrani JC, Ruiz-Rivero O, Fos M, García-Martínez JL. 2008. Auxin-induced fruit-set in tomato is mediated in part by gibberellins. The Plant Journal 56, 922–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinozaki Y, Hao S, Kojima M et al. 2015. Ethylene suppresses tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit set through modification of gibberellin metabolism. The Plant Journal 83, 237–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer H, Beltrán JP, Huijser P, Pape H, Lönnig WE, Saedler H, Schwarz-Sommer Z. 1990. Deficiens, a homeotic gene involved in the control of flower morphogenesis in Antirrhinum majus: the protein shows homology to transcription factors. EMBO Journal 9, 605–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo-Silveira M, Marsch-Martínez N, de Folter S. 2014. Unraveling the signal scenario of fruit set. Planta 239, 1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. 2000. Two-component signal transduction. Annual Review of Biochemistry 69, 183–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud H, Hale CJ, Feng S, Caro E, Jacob Y, Michaels SD, Jacobsen SE. 2012. DNA methyltransferases are required to induce heterochromatic re-replication in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics 8, e1002808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson PA. 1969. The effect of applied growth substances on development of the strawberry fruit: II. Interactions of auxins and gibberellins. Journal of Experimental Botany 20, 629–647. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Jones B, Li Z, Frasse P, Delalande C, Regad F, Chaabouni S, Latché A, Pech JC, Bouzayen M. 2005. The tomato Aux/IAA transcription factor IAA9 is involved in fruit development and leaf morphogenesis. The Plant Cell 17, 2676–2692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Dong Y, Morris BA. 2001. Parthenocarpic apple fruit production conferred by transposon insertion mutations in a MADS-box transcription factor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 98, 1306–1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerega NJ, Ragone D, Motley TJ. 2004. Complex origins of breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis, Moraceae): implications for human migrations in Oceania. American Journal of Botany 91, 760–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]