Abstract

Objectives

We assessed potential benefits for older Americans of reducing risk factors associated with dementia.

Methods

A dynamic simulation model tracked a national cohort of persons 51 and 52 years of age to project dementia onset and mortality in risk reduction scenarios for diabetes, hypertension, and dementia.

Results

We found reducing incidence of diabetes by 50% did not reduce number of years a person ages 51 or 52 lived with dementia and increased the population ages 65 and older in 2040 with dementia by about 115,000. Eliminating hypertension at middle and older ages increased life expectancy conditional on survival to age 65 by almost 1 year, however, it increased years living with dementia. Innovation in treatments that delay onset of dementia by 2 years increased longevity, reduced years with dementia, and decreased the population ages 65 and older in 2040 with dementia by 2.2 million.

Conclusions

Prevention of chronic disease may generate health and longevity benefits but does not reduce burden of dementia. A focus on treatments that provide even short delays in onset of dementia can have immediate impacts on longevity and quality of life and reduce the number of Americans with dementia over the next decades.

Keywords: Caregiving, Health care policy, Health outcomes, Prevention

Over the past 50 years, health and functional status of the American population has continued to improve (Freedman et al., 2004; Lakdawalla, Bhattacharya, & Goldman, 2004). These health gains have been valued as high as 50% of gross domestic product (Murphy & Topel, 2006). But these improvements do not come without economic costs. The United States has devoted an ever-increasing share of its income to health care over that same period. And although advances in attacking diseases have extended life, recent evidence suggests they may not extend healthy life at older ages (Crimmins, Zhang, & Saito, 2016). Public programs are also under enormous fiscal pressure; Medicare spending alone is projected to more than double as a share of national income—from 3.7% today to 7.3% in 2050 (Congressional Budget Office, 2012). Perhaps nowhere is the challenge more apparent than in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Spending on persons with these diseases is high and growing and the need to address the economic and social costs of dementia increases in urgency as the baby boom generation ages and life expectancy continues to rise (Zissimopoulos, Crimmins, & St Clair, 2014).

Quantifying the precise scale of the burden and projecting future needs has proved challenging. Studies on the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias have produced a wide range of numbers (Brookmeyer et al., 2011). Variation arises from study sample, disease definition, and methodology and use of nonnationally representative data sources. Langa and colleagues (2005) produced nationally representative prevalence estimates of cognitive impairment without dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias based on the Aging Demographics and Memory Study (ADAMS). Estimates of Alzheimer’s disease in 2002 from ADAMS were almost 50% less than estimates from the Chicago Health and Aging Project (Wilson et al., 2011). Several recent studies found declines in prevalence of dementia in the United States (Crimmins, Saito, & Kim 2016; Langa et al., 2017). Reasons for the decline are less well-understood. As discussed in Langa (2017), the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors associated with increasing the risk for dementia, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes are on the rise while the intensity of treatment for these diseases have also increased. For example, the use of effective cholesterol lowering medication, statins, has increased from 17.8% to 25.9% among Americans ages 40 and older (Gu et al., 2014). The higher levels of educational attainment in successive birth cohorts, contributing to cognitive reserve, may also be an important factor contributing to declining prevalence of dementia.

A recent publication by the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention and Care placed renewed focus on prevention of dementia through the reduction of risk factors such as by better treatment and management of disease such as hypertension and diabetes, improving childhood education, increasing exercise, reducing smoking, and maintaining social engagement (Livingston et al., 2017). Several studies have used extrapolated trends in disease to estimate future prevalence, accounting for changing health of younger cohorts (Hurd, Martorell, & Langa, 2015) or to simulate hypothetical improvements in health to understand the impact on future dementia prevalence (Barnes and Yaffe, 2011; Norton, Matthews, Barnes, Yaffe, & Brayne, 2014;). These studies do not simultaneously account for the dynamic interplay between diseases and importantly, between disease and mortality. Reductions in the prevalence of one vascular risk impacts the likelihood of other vascular risks and will likely increase survival into years of life at higher risk of acquiring dementia so reduction in mortality from other diseases will leave more people at risk of dementia. We know of no studies that simultaneously investigate these relationships in order to quantify the impact on future rates of dementia.

Microsimulation modeling based on nationally representative microdata provides important insight into future rates of dementias and the burden of disease and identifying which individual characteristics, and where along the disease trajectory targeted intervention would have the largest impact on future prevalence and costs. The few models that use dynamic microsimulation have data and methodological limitations that constrain their ability to project impacts of changing population health and demographics (Alzheimer’s Association (2015); Sloane et al., 2002). For instance, estimates have been based on data from several different studies using a variety of samples, study designs and distinctly different definitions of disease. Importantly, transition rates to dementia had to be assumed because of the absence of reliable population-based data on rates of onset. An exception is a study by Zissimopoulos et al. (2014) that uses dynamic microsimulation and nationally representative data to estimate transitions to Alzheimer’s disease and forecast the economic benefits of hypothetical innovations in treatment that delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease; this study, however, did not evaluate the value of different health scenarios in changing the future of Alzheimer’s disease.

In this study, we extend prior work with the use of nationally representative, longitudinal data to estimate models of incident Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias (hereinafter “dementia”) using a rich set of risk factors that include demographic, socioeconomic status, disease conditions, and health behaviors. We model onset of risk factors associated with dementia and account for the interdependent and dynamic associations of multiple risk factors and the impact of these risk factors on both morbidity and mortality. Utilizing dynamic microsimulation, we assess the effects of hypothetical reductions in diabetes and hypertension—diseases correlated with dementia—on dementia prevalence, life expectancy and number of years living with dementia for a nationally representative cohort of Americans aged 51 years and older. We compare the value of these health improvements to the value of a new treatment that delays the onset of dementia by 2 years. Second, we project population prevalence of dementia over four decades under different assumptions about population health and potential innovation in prevention or disease progression while accounting for changes in population characteristics such as the racial and ethnic composition and health of the future elderly adults. We address limitations of prior studies by using data from a rich, population-based longitudinal data source, the Health and Retirement Study and employing dynamic simulation methods based on an individual’s actual cognitive and functional changes over time, changes in risk factors associated with dementia such as heart disease and stroke, while accounting for the nonindependence of risk factors and the dynamics of their dependence, and their impact on mortality.

Methods

Data

The Health and Retirement study (HRS) is a nationally representative biannual survey of the health, cognition, disability, work, and economic status of Americans over age 50, conducted since 1992 and ongoing. We use data from seven survey waves, years 2000–2012. Our study sample of 27,734 (114,472 person-waves) includes all HRS participants ages 51 years or older, living in the community or in nursing homes. Supplementary Appendix Table 1 shows sample characteristics for survey year 2010.

Dementia

Cognitive functioning of HRS respondents is assessed at each wave using an adapted version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. HRS imputed these measures when missing because they are not randomly missing, but tend to be missing for the more cognitively impaired. The method is described in Fisher et al. (2013). When a respondent does not do the cognitive assessment, cognitive status is determined using information provided by a proxy respondent, typically a spouse or other family member (see Ofstedal, Fisher, & Herzog 2005). We assign cognitive state as with dementia, mild cognitive impairment without dementia, or normal based on scores from the assessments using an approach similar to that of Langa et al. (2017) which is described in Crimmins, Kim, Langa, & Weir (2011). We sum score of 3 cognitive assessments (range 0–27): immediate and delayed word recall (0–20); counting down from 100 by 7’s test score (0–5); and counting back from 20 (0–20). For proxy interviews, the cognition scale (range 0–11) sums the following: number of instrumental activities of daily living (0–5); interviewer impairment rating (0 = no cognitive limitations, 1 = some limitations, 2 = cognitive limitations); and proxy informant’s rating of the respondent’s memory (from 0 [excellent] to 4 [poor]). Cognition scores range as follows: 0–6 = with dementia, 7–11 = mild impairment, no dementia, and 12–27 = normal. Proxy scores are as follows: 0–2 = normal, 3–5 = mild impairment, no dementia, and 6–11 = with dementia. Both proxy and nonproxy scores are combined into one variable.

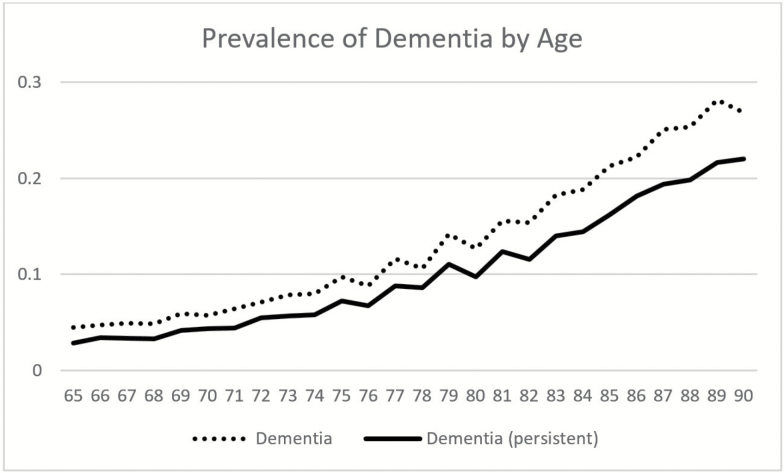

When we examine individuals over waves of the data, we find that individuals may transition into and out of dementia. We use persistent dementia as our definition of dementia in this study. In order to be categorized as having persistent dementia, we require one wave with dementia and evidence of continued cognitive impairment (either CIND or dementia) in the subsequent wave. If the respondent with one wave of dementia dies before the subsequent wave, we assume he or she had dementia before dying. Figure 1 shows differences in prevalence of dementia based on single wave assessment as is done in most studies and based on multiple wave (persistent) assessment as used in this study. At age 85, the difference in prevalence is 5 percentage points (21% compared to 16% based on persistent dementia). In the subsequent analyses, we use the persistent measure of dementia throughout. Prevalence at age 65, based on the multiple wave definition of dementia is 2.8% and 4.4% at age 71. Plassman and colleagues (2007) report a prevalence rate of 5.0% for ages 71–79 based on the U.S. Aging Demographic and Memory Study (ADAMS). ADAMS provides the first national prevalence estimates of dementia based on consensus diagnosis. Our reported prevalence is higher than that reported by the Alzheimers’s Society in the United Kingdom based on a synthesis of best available evidence (Knapp et al., 2014). They report prevalence rates of 0.9% for ages 60–64 and 1.7% for ages 65–69. Population differences, such as the higher rates of dementia among Hispanics and blacks in the United States are likely contributors to the difference.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of dementia by age for two definitions of dementia. Note: Health and Retirement Study Waves 2000 to 2012. Dementia definition based on single wave cognitive status, dementia (persistent) based on at least two waves of dementia or low cognitive score.

Methods Overview

Simulation modeling builds on the Future Elderly Model (FEM), a well vetted and validated, dynamic economic-demographic microsimulation model. The FEM has been at the root of dozens of important papers in health and social policy issues facing the elderly adults in the United States. Its ongoing development is supported by the National Institute on Aging through the USC Roybal Center for Health Policy Simulation. Key features of this microsimulation model are: (a) the use of longitudinal data on individuals followed over time that allows for more heterogeneity in behavior than cell based approaches; (b) entering cohorts reflect trends in demographic characteristics, health, and disease of younger cohorts; (c) both health and economic outcomes are estimated as well as models of public entitlement revenues and costs. We further develop this model for projecting dementia prevalence and the impact of changes in population health and treatment for disease on dementia prevalence. Technical details of the architecture of the FEM for projecting dementia, including simulations methods, data, models and their estimates are provided in the Technical Appendix.

Using 7 waves of data from the HRS, we estimate models of onset of dementia based on a sample of respondents ages 65 years and older. We use a rich set of covariates to obtain high quality estimates of dementia incidence rates representative of the older U.S. population. These models as well as other models of onset of chronic disease conditions and mortality feed the simulation model to produce future dementia prevalence estimates, and estimates of life expectancy and dementia-free years of life.

Dementia Model

We model the transition to dementia, conditional on survival. Using our persistent measure of dementia, we treat dementia as an absorbing state. We estimate a Markov model using a probit model and covariates include age, age-squared, sex, education (less than high school, high school, some college or higher), race (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, black), instrumental activity of daily living (difficulty with any), BMI (underweight, normal, obese), smoking status, and existence of disease conditions correlated with dementia (diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, stroke), and other health conditions (lung disease, cancer). We estimate the dementia model for a sample of respondents aged 65 years and older because of the low likelihood of dementia at younger ages and because the measure of dementia we use has been validated using ADAMS (Crimmins et al., 2011) for older, not younger ages (e.g., ages 51–65). Supplementary Appendix Table 2 shows model estimates of incident dementia and Supplementary Appendix Table 3 shows incidence rate per 1,000 person years. The numbers reported in Supplementary Appendix Table 3 are similar to those reported by Tom et al. (2015) based on Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study, a prospective cohort study of dementia who report for six age groups incidence rates per 1,000 person years: ages 65–69: 5.4; 70–74: 9.4; 75–79: 19.3; 80–84: 46.4; 85–89: 74.2; 90+: 105. Our estimates are also in line with Matthews et al. (2005) who report for ages 75–79, 80–84, and 85+ incidence rate of 14.5, 26.5, 68.5, respectively. Fratiglioni, De Ronchi, & Agüero-Torres (1999) review incidence data for dementia in the international literature in the last 10 years. Results from 15 incidence studies reported from 1989 to 1999 found incidence ranged 0.8–4.0 per 1,000 person years in persons ages 60–64 and 49–135.7 per 1,000 person years for population 95+.

Health Models

In addition to modeling onset of dementia, in order to understand the dynamic interplay of cognition and other diseases we also estimate a probit (for binary outcomes) and ordered probit (for categorical outcomes) models, for a sample of all respondents aged 51 years and older, (a) incidence of health conditions such as heart disease, cancer, diabetes, hypertension, stroke; (b) functional status, including five activities of daily living, three instrumental activities of daily living; (c) mortality. Models of functional status, the likelihood of developing a health condition and mortality will depend on age, gender, education, race, ethnicity, body mass index, smoking status, and health. Supplementary Appendix Table 4 illustrates the included covariates in these models. All health conditions, functional states, and risk factors are modeled using first-order Markov processes of a 2-year transition that control for baseline unobserved factors using health variables collected at baseline. We found these to be effective controls as revealed by goodness-of-fit tests. Dementia enters as a key covariate in the mortality model and our model estimates reveal that dementia increases the likelihood of death by 3 percentage points (model estimates for mortality and health models provided in Supplementary Technical Appendix).

Microsimulation

Transition models for health conditions, functional status, mortality, and dementia are estimated from multiple waves of the HRS. The estimates from all models are used to predict the health and cognitive paths of surviving individuals. The simulated cohort is representative of HRS respondents ages 51 or 52 (n = 1,030) from the 2010 HRS. The mortality model predicts who survives over the next 2 years and the dementia model predicts who will have onset of dementia. We continue the simulation until everyone in the cohort would have died. We conduct the simulation 500 times and average the cohort outcomes. We implement scenarios (described in detail below) by changing the transition probabilities for onset of diabetes and hypertension, and for one scenario, the transition probability for dementia. In other scenarios, we change health status at age 50.

Additionally, we estimate the number of Americans over age 50 with dementia each year until 2040. For these projections, we begin with the HRS population over age 50 in 2010. Each year a new cohort of middle age adults will enter the simulation and their health and characteristics will reflect trends in disability, obesity, smoking, and chronic disease among younger populations based on projections from the National Health Interview Study, and the Current Population Survey and the Census Bureau. Using the estimated coefficients from our multivariate models, for example, of dementia, onset of disease, mortality (see Supplmentary Technical Appendix for model estimates), we predict the outcome for each individual at each point in time. Individuals who survive to the next year are used to calculate prevalence of dementia each year from 2010 to 2040.

Scenarios

We consider three types of interventions: treatment for hypertension, treatment for diabetes, and treatment that prevents dementia onset. In the first two types of scenarios, the effect on dementia is indirect through the improvements in health conditions that affect dementia onset. That is, in our models, we estimate that hypertension increases risk for heart disease and stroke so a reduction in hypertension reduces risk of both. We estimate diabetes increases risk of heart disease, stroke, high blood pressure, and dementia. A reduction in diabetes reduces risk of dementia directly and through its effects on heart disease, stroke and high blood pressure. Estimates from models of onset of diseases (e.g., stroke, diabetes) are not shown here but are available.

In the third type of scenario, we consider the direct effect of a hypothetical treatment that delays the onset of dementia by 2 years. That is, we assume onset and prevalence of all other risk factors associated with dementia are unchanged but the risk of onset of dementia is reduced for example, through a drug that slows dementia pathology before it would be diagnosed as dementia.

All scenarios also affect the risk of acquiring dementia through a direct and indirect effect on dementia and on mortality. For example, reductions in hypertension reduce likelihood of dementia directly and also indirectly by reducing likelihood of subsequent stroke and diabetes. Reductions in hypertension also reduce likelihood of death directly and indirectly through these other disease pathways. That is, better health reduces risk of death. Increases in longevity may increase dementia risk because people live to older ages and age is a key predictor of dementia risk. The scenarios are used to estimate future prevalence of dementia and potential benefits to life expectancy, years of dementia-free life and lifetime risk of dementia for a cohort who are ages 51 and 52 in 2010 (birth cohorts 1958 and 1959). We compare these health improvement scenarios to the status quo of no reduction in hypertension or diabetes or innovations for the treatment of dementia.

Results

Table 1 shows the effects of the different scenarios, conditional on survival to age 65, on remaining life expectancy, average number of years lived with dementia for the entire cohort, average number of years lived with dementia, conditional on acquiring dementia at some point before death and the lifetime probability of developing dementia. Under conditions reflecting the status quo, life expectancy at age 65 is expected to be 21.48 years for this cohort which has survived to age 65 and whose progress is simulated through the remainder of life. On average, a cohort member will live with dementia for 2.94 years (includes those who never acquire dementia). Among the individuals in the cohort who get dementia, the average number of years living with dementia is 5.19 years. The lifetime risk of developing dementia is 34.7%.

Table 1.

Average Years of Remaining Life and Years with Dementia in a Cohort Aged 51 or 52 Years, Conditional on Survival to Age 65, by Status quo and Intervention Scenarios

| Life expectancy | Years with dementia | Years with dementia conditional on dementia | Lifetime risk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenarios | (years) | (years) | (years) | (%) |

| (0) Status quo | 21.48 | 2.94 | 5.19 | 34.7 |

| (1) Reduce incident hypertension 50% | 21.84 | 3.02 | 5.22 | 35.4 |

| (2) No incident hypertension | 22.01 | 3.19 | 5.21 | 36.8 |

| (3) No hypertension at age 50, no incident | 22.35 | 3.37 | 5.26 | 38.3 |

| (4) Reduce incident diabetes 50% | 21.84 | 3.02 | 5.22 | 35.4 |

| (5) Delay dementia 2 years | 21.63 | 2.43 | 4.29 | 29.3 |

Note: FEM simulation results using data from HRS waves 2000 to 2012. Years are measured conditional on survival to age 65.

Under scenarios that reduce hypertension and diabetes, life expectancy after age 65 increases relative to the status quo. Reducing incident hypertension by 50% increases life-years by 0.36 years; eliminating all onset of hypertension after age 51 increases life expectancy by about twice as much or an additional 0.53 years. A hypertension “cure” (scenario 3) or eliminating all hypertension among those aged 50 years and older increases life years by 0.87 years. Reducing diabetes incidence by 50% increases life expectancy by 0.36 years. There is a small increase in life expectancy relative to the status quo (0.15 years) associated with delaying dementia onset by 2 years (scenario 5).

Treatments to reduce hypertension and diabetes increase the average number of years living with dementia because the improved health increases longevity and this increase outweighs the benefits of better health in reducing dementia onset. A “cure” for hypertension results in the largest number of years living with dementia (3.37 years) which is an additional 0.43 years relative to the status quo. Reducing incident diabetes by 50% (scenario 4) has a small effect on years living with dementia (increase of 0.08 years). Only treatments that delay dementia onset (scenario 5) both increase life expectancy and reduce years living with dementia. Across the entire cohort, years living with dementia would be reduced to 2.43 with a delay of two years in dementia onset rates, a reduction of 0.51 years relative to the status quo. Conditional on acquiring dementia under the status quo, delaying dementia by 2 years results in an average of 0.90 fewer years with dementia relative to the status quo.

Reductions in hypertension and diabetes increase the likelihood of developing dementia over one’s lifetime. Percentage point increases range from 0.6 (reduce incident hypertension or diabetes by 50%) to 3.6 (no initial hypertension and no onset). Delaying onset of dementia by 2 years reduces the likelihood of developing dementia over one’s lifetime by 5.4 percentage points relative to the status quo (from 34.7 to 29.3%).

Table 2 shows the number of people alive at ages 65 and 66 and at ages 85 and 86 and the number of individuals with dementia at ages 65/66 and ages 85/86 under the different scenarios. Because of the data structure, we combine the two single ages into 2-year groups. Under the status quo, there are 7.90 million people ages 65/66 and 3.57 million people ages 85/86. At ages 65/66, there are about 281,000 people with dementia representing 3.5% of the population at those ages. At ages 85/86, just over 937,000 have dementia or 26% of the population ages 85/86. Treatments for hypertension and diabetes have little effect on the number of Americans with dementia at ages 65/66 relative to the status quo but result in increases in the number of Americans ages 85/86 with dementia. Only delaying the onset of dementia directly results in fewer Americans with dementia.

Table 2.

Total Number of Americans and Number with Dementia (millions): Ages 65 and 66; Ages 85 and 86

| Population (millions) | Population (millions) | Population w/dementia (millions) | Population w/dementia (millions) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenarios | Ages 65 and 66 | Ages 85 and 86 | Ages 65 and 66 | Ages 85 and 86 |

| (0) Status Quo | 7.903 | 3.566 | 0.281 | 0.937 |

| (1) Reduce incident hypertension 50% | 7.916 | 3.644 | 0.282 | 0.959 |

| (2) No incident hypertension | 7.933 | 3.793 | 0.283 | 1.004 |

| (3) No hypertension age 50, no incident | 8.035 | 4.032 | 0.291 | 1.078 |

| (4) Reduce incident diabetes 50% | 7.931 | 3.742 | 0.278 | 0.961 |

| (5) Delay dementia 2 years | 7.909 | 3.625 | 0.220 | 0.762 |

Note: FEM simulation results using data from HRS waves 2000 to 2012.

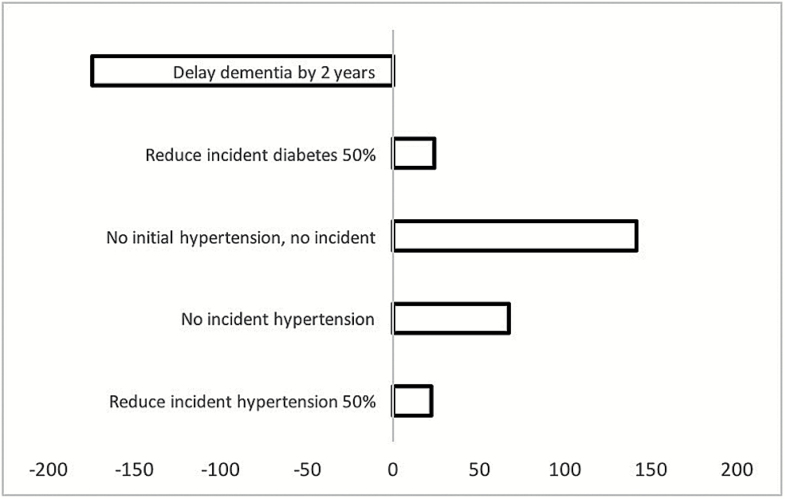

Figure 2 shows changes in the number of Americans at ages 85/86 under the scenarios relative to the status quo. Reducing incident diabetes (scenario 4) results in a small increase in the number of Americans ages 85/86 with dementia (23,805 persons). Curing hypertension (scenario 3) results in the largest increase in number of Americans with dementia at ages 85/86 (141,427 persons). Delaying onset of dementia (scenario 5) reduces the number of Americans with dementia at ages 85/86 by 175,199 persons relative to the status quo.

Figure 2.

Difference in number of Americans ages 85 and 86 with dementia: number under scenario less number under status quo.

Table 3 shows projections of the number of Americans with dementia for the entire population age 65 and older from 2016 to 2040 for the status quo, and for the one scenario that reduced the number of Americans with dementia based on cohort simulations (delay dementia scenario). We also compare to scenarios that reduce incident diabetes or incident hypertension, the two scenarios that resulted in small increases to the total number with dementia above the status quo. This population projection accounts for changes in the characteristics of the population such as changes in age structure, educational attainment, race, and ethnic distribution. The number of Americans ages 65 and older with dementia will grow from 6.49 million in 2016 to 11.6 million in 2040. By 2040, if new treatments can delay onset of dementia by 2 years, we forecast that there will be 2.16 million fewer Americans with dementia. In contrast, if we succeed in reducing incident diabetes by 50% in middle age, we will have about 120,000 more Americans with dementia in 2040 compared to the status quo. Successfully reducing incident hypertension by 50% results in just over 200,000 more Americans with dementia in 2040.

Table 3.

Population of Americans Ages 65 and Older (millions) with Dementia Under Status Quo and Three Scenarios

| Year | Status Quo | Delay dementia 2 years | Reduce incident diabetes 50% | Reduce incident hypertension 50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 6.49 | 4.98 | 6.48 | 6.49 |

| 2018 | 6.88 | 5.41 | 6.85 | 6.87 |

| 2020 | 7.24 | 5.78 | 7.21 | 7.24 |

| 2022 | 7.60 | 6.12 | 7.59 | 7.62 |

| 2024 | 7.95 | 6.45 | 7.96 | 8.00 |

| 2026 | 8.35 | 6.77 | 8.36 | 8.41 |

| 2028 | 8.77 | 7.12 | 8.79 | 8.85 |

| 2030 | 9.22 | 7.50 | 9.25 | 9.32 |

| 2032 | 9.70 | 7.89 | 9.74 | 9.81 |

| 2034 | 10.17 | 8.28 | 10.23 | 10.31 |

| 2036 | 10.68 | 8.69 | 10.75 | 10.84 |

| 2038 | 11.18 | 9.09 | 11.27 | 11.35 |

| 2040 | 11.66 | 9.51 | 11.78 | 11.86 |

Discussion

Middle-age Americans today are living longer than ever before in part due to our success in treating cardiovascular and other diseases. Recent work has found advances in attacking diseases may not extend healthy life at older ages and this has broad implications families and governments who support people with disabilities (Crimmins et al., 2016; Jagger et al., 2016).

In this study, we found that progress in combating chronic disease for future elderly adults in the United States will come with increased risk of acquiring dementia. For a cohort of middle-age Americans, ages 51 and 52 in 2010, life expectancy at age 65 is expected to be 21.48 years, conditional on survival to age 65. On average, a 51- or 52-year-old American in 2010 will live with dementia for 2.94 years. Among the individuals in the same cohort who get dementia, the average number of years living with dementia is 5.19 years. The lifetime risk of developing dementia is 34.7%. This estimate is similar to recent estimates based on a national representative sample of Americans ages 71 and older from the Aging Demographic and Memory Study that report lifetime risks for a 1940 birth cohort of 31% and 37% for men and women, respectively (Fishman, 2017). Our estimates and Fishman’s are higher than reports from the Framingham Heart Study (21.1% for women and 11.6% for men as reported by the Alzheimer’s Association) and other studies of cohorts that are not representative of the U.S. population. This is expected given that the Framingham sample is primarily of European decent and African Americans and Hispanic have higher age specific rates of dementia than whites.

Reducing diabetes and hypertension are key priorities for improving public health but will not reduce the significant and growing public health concern of dementia. We find that reducing incidence of diabetes in the populations ages 51 and older results in more years living with dementia and increases the population ages 65 and older in 2040 with dementia by about 120,000. Eliminating hypertension at middle and older ages increases life expectancy conditional on survival to age 65 by almost 1 year however, it too increases the years living with dementia. Reductions in hypertension and diabetes increase the likelihood of developing dementia over one’s lifetime. Increases range from 0.6 percentage points (reduce incident hypertension or diabetes by 50%) to 3.6 percentage points (no initial hypertension and no onset).

Treatments to reduce hypertension and diabetes increase the average number of years living with dementia because the improved health increases longevity and this increase outweighs the benefits of better health in reducing dementia onset. While earlier studies suggested that reducing modifiable risk factors such as prevalence of hypertension, obesity and diabetes, physical activity smoking, and improving access to education may reduce the burden of Alzheimer’s disease, they did not account for the reduction in mortality resulting from improved vascular health and higher socioeconomic status (Barnes and Yaffe, 2011; Norton et al., 2014).

Moreover, rising educational levels are unlikely to drive reductions in dementia in the United States in the future. The average education level of the U.S. population ages 65 rose dramatically between 1980 and 2010 and this may have driven prevalence rates of dementia lower during this time period; however, increase in education will likely not have a continued effect. Goldin and Katz (2007) show that average years of education for a 65-year old increased by 16% between 1990 and 2010 but will only rise about 7% between 2010 to 2030 and if the current trend continues, we will see little to no growth in education of older Americans going forward. Indeed, census data show a convergence of education attainment after decades of growth: 87% of the population ages 25 and older have completed high school in 2012 and 89% of the population ages 25–29% have completed high school (Sieban and Ryan, 2012). This is in stark contrast to continued rising education levels in other industrialized countries (OECD (2016)) that are projected to contribute to lower dementia prevalence in the future (Norton et al., 2014).

We already have effective treatments to prevent or significantly reduce type 2 diabetes and these were described in a meta-analysis by Gillies et al. (2007). For hypertension, the Trials of Hypertension Prevention (Stevens et al., 2001) found that a 3-year program focused on dietary change, physical activity, and social support reduced the incidence of hypertension among middle-aged participants. Although currently there are no effective treatments for preventing dementia, we show that you do not have to cure dementia to have an impact. Only treatments that directly impact onset of dementia both increase longevity and reduce years living with dementia, reduce lifetime risk, and reduce the number of people with dementia relative to the status quo. Even a delay of 2 years has significant value; the number of years living with dementia, conditional on dementia, for a cohort of middle-aged American is reduced by almost 1 year: from 5.2 years to 4.3 years. In terms of quality of life and economic gains, an additional year dementia free has enormous value to individuals and families. By 2040, there will be 2.2 million fewer Americans with dementia if treatments result in delayed onset.

Delaying the onset of dementia may be within our grasp and the scientific community is cautiously optimistic about developing treatments that will delay or prevent dementia. While there is no treatment for Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia, at this time, currently used drugs such as cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine already delay progression of symptoms by about 2 years in those with Alzheimer's disease (Rountree, Atri, Lopez, & Doody, 2013). Recent improvements in diagnosis and identification of risk allow us to identify people with prodromal Alzheimer’s which means treatment can begin before the final stage of disease (Xia et al., 2017). Researchers have identified more than 25 additional genes involved in Alzheimer’s disease that will help identify possible drug targets (Jonsson et al., 2013). As of yet, new therapies have not confirmed their ability to prevent or delay Alzheimer's disease but clinical trials for a host of new treatments are underway and brain-imaging technology in combination with drug therapy is increasing our understanding of the efficacy of drug treatment.

It is also possible that more systemic approaches to delaying the process of aging may affect the onset of Alzheimer’s along with other diseases. As an example, synolytic drugs which target senescent cells may also delay Alzheimer’s onset (Kirkland and Tchkonia, 2017). We already have treatments for other diseases that may reduce risk of Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia. A potential therapy may be found in statins, the most popular cholesterol-lowering medication in the United States, with 25.9% of adults aged 40 years and older using them in 2012 (Gu et al., 2014). A recent population based study found statins were associated with a reduction in risk of Alzheimer’s disease (Zissimopoulos, Barthold, Brinton, & Joyce, 2016) confirming early evidence from a large cohort study of veterans (Wolozin et al., 2007). While evidence from two large randomized control trials found no effect, both examined short term use of statins and if statins affect early stage of disease or have small cumulative effects, we would not expect them to uncover this relationship. Another widely used drug for diabetes, metformin, has also been suggested as a drug which could slow the overall aging process including cognitive decline and will be included in clinical trials soon (Barzilai, Crandall, Kritchevsky, & Espeland, 2016).

Limitations

The results of our study will be affected by measurement error in dementia status. However, we chose a conservative method for measuring dementia prevalence and onset by requiring that dementia status must be confirmed by a second wave of low cognitive scores.

Despite the inclusion in the model of multiple potential confounders between a particular risk factor and dementia, causality in this study, like others, remains questionable. Moreover, in our modeling, we assumed that health conditions followed a Markovian process. That is, risk factors and health conditions in the prior period determine future health, mortality, and functional outcomes. The model fit well over the time period we used however we do not know if this will sustain over a longer time period. Further research on duration dependence of disease will inform future work.

Diabetes and hypertension are just two of several chronic disease conditions associated with dementia. We also examined the effects of a reduction in heart disease as a proxy for improving overall cardiovascular health in middle age. We found similar effects to independently reducing hypertension or diabetes: small increases in longevity and increases in the years spent with dementia and the size of the population with dementia. That said, overall improvements in cardiovascular health and a healthy vascular system from young age to old age may still have some potential to both increase life-expectancy and reduce dementia. Moreover, if the reduction in incidence of a risk factor, such as hypertension is through, for example, a drug treatment that has a direct effect on dementia (other than the effect through reducing hypertension), there could be an additional direct effect on reducing risk of dementia with unknown impacts on mortality.

Conclusion

With advances in treatment for chronic conditions that affect risk of dementia and likely new innovations in diagnosis and treatments to reduce risk of dementia comes an urgent need to understand their impact on the health and health care expenditures of an aging population. This study used dynamic micro simulation as a way to understand the impacts for a cohort of middle age American as well as for all Americans over age 50 in the coming decades. Hypothetical situations were applied to shed light on the effects of disease-modifying treatments or cures. Our findings show that while prevention of chronic disease may generate health and longevity benefits, they do not reduce burden of dementia. A focus on therapies that provide even short delays in onset of dementia can have immediate impacts on longevity and quality of life and reduce the number of Americans with dementia over the next decades.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data is available at The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences online.

Funding

The work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (grant numbers 5P30AG024968, P30AG017265, P30AG012846).

Author Contributions

J. Zissimopoulos planned the study, supervised the data analysis, and wrote the paper. E. Crimmins helped to plan the study and contributed to revising the paper. P. St.Clair helped to plan the study and contributed to statistical analyses. B. Tysinger performed statistical analyses and contributed to revising the paper.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alzheimer’s Association (2015). Changing the Trajectory of Alzheimer’s Disease: How a Treatment by 2025 Saves Lives and Dollars. Washington, DC: Alzheimer’s Association. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D. E., & Yaffe K (2011). The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. The Lancet Neurology, 10, 819–828. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70072-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilai N., Crandall J. P., Kritchevsky S. B., & Espeland M. A (2016). Metformin as a tool to target aging. Cell Metabolism, 23, 1060–1065. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer R., Evans D. A., Hebert L., Langa K. M., Heeringa S. G., Plassman B. L., & Kukull W. A (2011). National estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 7, 61–73. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. M., Kim J. K., Langa K. M., & Weir D. R (2011). Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: The health and retirement study and the aging, demographics, and memory study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66B(Suppl 1), i162–i171. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. M., Saito Y., & Kim J. K (2016). Change in cognitively healthy and cognitively impaired life expectancy in the United States: 2000-2010. SSM - Population Health, 2, 793–797. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. M., Zhang Y., & Saito Y (2016). Trends over 4 decades in disability-free life expectancy in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 106, 1287–1293. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office, The 2012 Long-Term Budget Outlook. CBO Publication 43288; www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/06-05-Long-Term_Budget_Outlook.pdf

- Fratiglioni L., De Ronchi D., & Agüero-Torres H (1999). Worldwide prevalence and incidence of dementia. Drugs & Aging, 15, 365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher G. G., Hassan H., Faul J. D., Rodgers W. L., & Weir D. R (2013). Health and retirement study imputation of cognitive functioning measures 1992–2010. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19, 231–242. Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/. [Google Scholar]

- Fishman E. (2017). Lifetime risk of dementia in the U.S. Demography, 54, 1897–1919. doi:10.1007/s13524-017-0598-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman V. A., Crimmins E., Schoeni R. F., Spillman B. C., Aykan H., Kramarow E., … Waidmann T (2004). Resolving inconsistencies in trends in old-age disability: Report from a technical working group. Demography, 41, 417–441. doi:10.1353/dem.2004.0022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies C. L., Abrams K. R., Lambert P. C., Cooper N. J., Sutton A. J., Hsu R. T., & Khunti K (2007). Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 334, 299. doi:10.1136/bmj.39063.689375.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin C., & Katz L. F (2007). Long-run changes in the wage structure: Narrowing, widening, polarizing. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 38, 135–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gu Q., Paulose-Ram R., Burt V. L., & Kit B. K (2014). Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003–2012. National Center for Health Statistics, 1–8. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db177.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd M. D., Martorell P., & Langa K (2015). Future monetary costs of dementia in the United States under alternative dementia prevalence scenarios. Journal of Population Ageing, 8, 101–112. doi:10.1007/s12062-015-9112-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger C., Matthews F. E., Wohland P., Fouweather T., Stephan B. C. M., & Robinson L;Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Collaboration.(2016). A comparison of health expectancies over two decades in England: Results of the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Lancet (London, England), 387, 779–786. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00947-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T., Stefansson H., Steinberg S., Jonsdottir I., Jonsson P. V., Snaedal J., … Stefansson K (2013). Variant of TREM2 Associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. The New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 107–116. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1211103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland J. L., & Tchkonia T (2017). Cellular senescence: A translational perspective. EBioMedicine, 21, 21–28. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp M., Comas-Herrera A., Wittenberg R., Hu B., King D., Rehill A., Adelaja B (2014). Scenarios of Dementia Care: What Are the Impacts on Cost and Quality of Life? London: Personal Social Services Research Unit, London School of Economics and Political Science. [Google Scholar]

- Lakdawalla D. N., Bhattacharya J., & Goldman D. P (2004). Are the young becoming more disabled?Health Affairs (Project Hope), 23, 168–176. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.23.1.168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa K. M., Larson E. B., Crimmins E. M., Faul J. D., Levine D. A., Kabeto M. U., & Weir D. R (2017). A comparison of the prevalence of dementia in the United States in 2000 & 2012. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, 177, 51–58. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa K. M., Plassman B. L., Wallace R. B., Herzog A. R., Heeringa S. G., Ofstedal M. B., … Willis R. J (2005). The aging, demographics, and memory study: Study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology, 25, 181–91. doi:10.1159/000087448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G., Sommerlad A., Orgeta V., Costafreda S. G., Huntley J., Ames D., … Mukadam N (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363–6 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews F., & Brayne C; Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study Investigators.(2005). The incidence of dementia in England and Wales: Findings from the Five Identical Sites of the MRC CFA Study. PLoS Medicine, 2, e193. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K. M., & Topel R. H (2006). The value of health and longevity. Journal of Political Economy, 114, 871–904. doi:10.3386/w11405 [Google Scholar]

- Norton S., Matthews F. E., Barnes D. E., Yaffe K., & Brayne C (2014). Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. The Lancet Neurology, 13, 788–794. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70136-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2016). Education at a Glance 2016: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 10.187/eag-2016-en. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ofstedal M. B., Fisher G. G., & Herzog A. R (2005). Documentation of cognitive functioning measures in the health and retirement study Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/.

- Plassman B. L., Langa K. M., Fisher G. G., Heeringa S. G., Weir D. R., Ofstedal M. B., … Wallace R. B (2007). Prevalence of dementia in the United States: The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. Neuroepidemiology, 29, 125–132. doi:10.1159/000109998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree S. D., Atri A., Lopez O. L., & Doody R. S (2013). Effectiveness of antidementia drugs in delaying Alzheimer’s disease progression. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 9, 338–345. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2012.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieban J., & Ryan C (2012). Educational attainment in the US: 2009. Washington, DC:US Census Bureau, P20—566 [Google Scholar]

- Sloane P. D., Zimmerman S., Suchindran C., Reed P., Wang L., Boustani M., & Sudha S (2002). The public health impact of Alzheimer’s disease, 2000-2050: Potential implication of treatment advances. Annual Review of Public Health, 23, 213–231. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.23.100901.140525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens V. J., Obarzanek E., Cook N. R., Lee I. M., Appel L. J., Smith West D., … Cohen J; Trials for the Hypertension Prevention Research Group (2001). Long-term weight loss and changes in blood pressure: Results of the Trials of Hypertension Prevention, phase II. Annals of Internal Medicine, 134, 1–11. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-1-200101020-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tom S. E., Hubbard R. A., Crane P. K., Haneuse S. J., Bowen J., McCormick W. C., … Larson E. B (2015). Characterization of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in an older population: Updated incidence and life expectancy with and without dementia. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 408–413. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.301935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson R. S., Weir D. R., Leurgans S. E., Evans D. A., Hebert D. A., Langa K. M., … Bennett D. A (2011). Sources of variability in estimates of the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimer’s and dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 7, 74–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolozin B., Wang S. W., Li N. C., Lee A., Lee T. A., & Kazis L. E (2007). Simvastatin is associated with a reduced incidence of dementia and Parkinson’s disease. BMC Medicine, 5, 20. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-5-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C., Makaretz S. J., Caso C., McGinnis S., Gomperts S. N., Sepulcre J., … Dickerson B. C (2017). Association of in vivo [18F]AV-1451 Tau PET imaging results with cortical atrophy and symptoms in typical and atypical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurology, 74, 427–436. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zissimopoulos J., Crimmins E., & St Clair P (2014). The value of delaying Alzheimer’s disease onset. Forum for Health Economics and Policy, 18, 25–39. doi:10.1515/fhep-2014-0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zissimopoulos J., Barthold D., Brinton R. D., & Joyce G (2016). Sex and race differences in the association between statin use and the incidence of Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurology, 74, 225–232. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.