Abstract

We demonstrate the formation and tuning of charged trion-polaritons in polymer-sorted (6,5) single-walled carbon nanotubes in a planar metal-clad microcavity at room temperature. The positively charged trion-polaritons were induced by electrochemical doping and characterized by angle-resolved reflectance and photoluminescence spectroscopy. The doping level of the nanotubes within the microcavity was controlled by the applied bias and thus enabled tuning from mainly excitonic to a mixture of exciton and trion transitions. Mode splitting of more than 70 meV around the trion energy and emission from the new lower polariton branch corroborate a transition from exciton-polaritons (neutral) to trion-polaritons (charged). The estimated charge-to-mass ratio of these trion-polaritons is 200 times higher than that of electrons or holes in carbon nanotubes, which has exciting implications for the realization of polaritonic charge transport.

Keywords: trion-polaritons, strong coupling, single-walled carbon nanotubes, microcavity

Exciton-polaritons

are hybrid

particles of light and matter that are formed when an optically active

material strongly couples to a resonant optical mode.1 In planar microcavities, these quasiparticles have been

observed for a wide range of materials from inorganic quantum wells

and bulk semiconductors,2−4 small organic molecules, and polymers5−8 to one- and two-dimensional semiconductors.9−12 One of the distinct properties

of exciton-polaritons is their low effective mass, which enables the

observation of phenomena like Bose–Einstein condensation13,14 and superfluidity,15,16 even at room temperature,17−20 leading to applications such as polariton lasers.21−24 Combining a low-mass polariton

with a (fractional) charge would result in a quasiparticle with a

very high charge-to-mass ratio that may lead to polariton-enhanced

charge transport under an applied electric field.25,26 Charged excitons are usually termed trions (X± or

T) and consist of a neutral exciton and an additional hole or electron.27 They absorb and emit light at lower energies

than the exciton27 and could be employed

to create trion-polaritons. Charged (or trion) polaritons were first

demonstrated in GaAs/AlAs quantum-well microcavities in the presence

of a two-dimensional electron gas25,28,29 and more recently in monolayers of transition metal

dichalcogenides30,31 at cryogenic temperatures. However,

to be able to observe trions and hence trion-polaritons at room temperature,

a large binding energy is necessary. The binding energies of both

excitons and trions dramatically increase when the dimensionality

of the system is reduced.32 Trions have

been experimentally observed at room temperature in doped monolayers

of transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)33,34 and more clearly in semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotubes

(s-SWCNTs).35−38 For s-SWCNTs the energy difference (ΔE) between

the trion and exciton depends on the diameter (d)

of the nanotube as  (where A and B are fitting parameters). ΔE represents the

sum of the trion binding energy and the exchange splitting. It ranges

between 100 and 200 meV in s-SWCNTs,35 compared

to only 30 meV in TMDs.33 For the latter,

the exact nature of the state is also currently under discussion.30,39 Aside from the very large trion binding energy, s-SWCNTs combine

a number of advantageous properties for potential trion-polariton

formation and its impact on charge transport. Similar to the excitonic

transitions in carbon nanotubes, trions exhibit a small Stokes shift.37 Although the maximum achievable trion absorbance

for a given s-SWCNT concentration or film thickness is about 4 to

5 times lower than that of the excitonic S11 transition,

it is still large enough to achieve strong coupling in medium quality

cavities when using dense films. In contrast to TMD materials, creating

thick films or stacks of s-SWCNTs does not substantially degrade their

optical and electronic properties.9 The

charge carrier mobilities in dense, solution-processed s-SWCNT networks

(5–50 cm2 V–1 s–1)40 are still very high. In addition,

both electron- and hole-doping are possible: chemically, electrochemically,

and electrostatically.35,36,41 After sorting and purification, monochiral samples of SWCNTs with

defined optical properties and narrow line widths can be obtained

that are suitable for optical as well as charge transport experiments.

The semiconducting nanotube species that is easiest to purify in large

amounts, the small-diameter (6,5) SWCNTs (d = 0.757

nm),42 exhibits trions with a line width

of about 40 meV and very high binding energies. The (6,5) trion at

1.07 eV is red-shifted by about 190 meV from the excitonic S11 transition36,37,43,44 and should thus be ideal for demonstrating

trion-polaritons at room temperature in suitable microcavities.

(where A and B are fitting parameters). ΔE represents the

sum of the trion binding energy and the exchange splitting. It ranges

between 100 and 200 meV in s-SWCNTs,35 compared

to only 30 meV in TMDs.33 For the latter,

the exact nature of the state is also currently under discussion.30,39 Aside from the very large trion binding energy, s-SWCNTs combine

a number of advantageous properties for potential trion-polariton

formation and its impact on charge transport. Similar to the excitonic

transitions in carbon nanotubes, trions exhibit a small Stokes shift.37 Although the maximum achievable trion absorbance

for a given s-SWCNT concentration or film thickness is about 4 to

5 times lower than that of the excitonic S11 transition,

it is still large enough to achieve strong coupling in medium quality

cavities when using dense films. In contrast to TMD materials, creating

thick films or stacks of s-SWCNTs does not substantially degrade their

optical and electronic properties.9 The

charge carrier mobilities in dense, solution-processed s-SWCNT networks

(5–50 cm2 V–1 s–1)40 are still very high. In addition,

both electron- and hole-doping are possible: chemically, electrochemically,

and electrostatically.35,36,41 After sorting and purification, monochiral samples of SWCNTs with

defined optical properties and narrow line widths can be obtained

that are suitable for optical as well as charge transport experiments.

The semiconducting nanotube species that is easiest to purify in large

amounts, the small-diameter (6,5) SWCNTs (d = 0.757

nm),42 exhibits trions with a line width

of about 40 meV and very high binding energies. The (6,5) trion at

1.07 eV is red-shifted by about 190 meV from the excitonic S11 transition36,37,43,44 and should thus be ideal for demonstrating

trion-polaritons at room temperature in suitable microcavities.

We previously demonstrated neutral exciton-polaritons with a large Rabi splitting of more than 110 meV in simple metal-clad microcavities with (6,5) SWCNTs that could be excited optically and electrically and for which the coupling strength was tunable by field-effect induced charge accumulation.9,45 Here, we report strong trion–photon coupling and observe emissive trion-polaritons at room temperature with an energy splitting of more than 70 meV. Reversible electrochemical doping of (6,5) SWCNTs in a metal-clad electrochromic cell enabled gradual tuning between neutral exciton-polaritons with ultrastrong coupling and charged trion-polaritons. The estimated charge-to-mass ratio was up to 200 times higher than that of electrons or holes in s-SWCNTs. Doped s-SWCNTs in microcavities thus represent a fascinating and tunable system to study polaritonic charge transport.

Results and Discussion

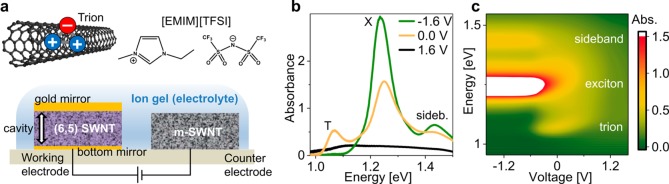

A simple planar electrochromic device geometry was used to vary the doping state of a dense nanotube film within a planar metal-clad microcavity. Purified polymer-sorted (6,5) SWCNTs were prepared by shear-force mixing42 and filtered to form a smooth and dense film (thickness ∼200 nm, see Figure S1 for absorbance spectra, Supporting Information). The film was transferred onto a gold working electrode (30 nm) on glass that also acted as a bottom mirror. Another dense, filtrated film of mixed metallic/semiconducting nanotubes (m-SWCNTs) was deposited next to it as the counter electrode (see Supporting Information for experimental details). Part of the (6,5) SWCNT film was covered with a thermally evaporated 120 nm thick layer of gold as the top mirror of the cavity. An iongel based on the ionic liquid [EMIM][TFSI] (see Figure 1a for molecular structure) was spin-coated onto the sample as an electrolyte to enable electrochemical doping, as previously shown for similar geometries.37,46 The final device structure is schematically illustrated in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

(a) Device layout of (6,5) SWCNTs embedded in a metal-clad microcavity that are electrochemically doped by applying a bias between the working and the counter electrode (mixed nanotubes, m-SWCNT). (b) Absorbance spectra of a representative (6,5) SWCNT film in the undoped (green), moderately hole-doped (orange) and highly doped (black) regime. (c) Contour plot of voltage-dependent absorbance of the (6,5) SWCNT film showing reduced exciton absorption and enhanced trion absorption for increasing hole doping (higher positive voltage). The maximum excitonic absorbance was 2.9 (at −1.6 V), for better visibility of the trion, the absorbance scale was restricted to a maximum value of 1.5.

As this device geometry corresponds to a typical electrochromic cell,46 we use the electrochemical convention for the assignment of electrodes and voltages. That is, when a positive voltage is applied to the cell the working electrode is polarized with holes. Anions of the iongel move toward the working electrode and form electric double layers around the (6,5) SWCNTs. This leads to hole-doping of the entire nanotube film (working electrode). Electrolyte cations move to the counter electrode with the mixed nanotubes and induce an equivalent number of electrons. The sample essentially acts as a planar supercapacitor with a semiconducting working electrode. Since all measurements were carried out in air and the water/oxygen redox couple suppresses electron conduction,47 no electron-doping was possible. Further, the (6,5) SWCNTs were slightly hole-doped by oxygen to various degrees,46 such that negative voltages had to be applied to reach the neutral state and the related maximum exciton emission/absorption.

Figure 1b shows the absorbance spectra of such a (6,5) SWCNT film (without cavity) in the three main doping regimes: The undoped/neutral regime (−1.6 V) is characterized by one main excitonic (X) absorption peak at 1.26 eV and one at 1.44 eV identified as the exciton–phonon sideband (sideb.) of the (6,5) nanotubes.48 Note that the absorbance can be tuned continuously by the applied voltage between the three regimes (see Figure S2, Supporting Information). In the moderately hole-doped regime (0.0 V), the oscillator strength of the exciton and phonon sideband is reduced and a third peak, attributed to the positively charged trion (T), appears at 1.07 eV.37 At very high hole-doping levels (+1.6 V), all three absorption peaks disappear and only a broad absorption band (H-band)49 remains. Figure 1c presents a more detailed contour plot of the absorbance spectra of the (6,5) SWCNT film for voltages between −1.6 V and +1.6 V that also reveals a slight blue-shift of the trion and exciton absorption of up to 30 meV with increasing hole doping. This shift is possibly caused by doping-induced band gap renormalization.50

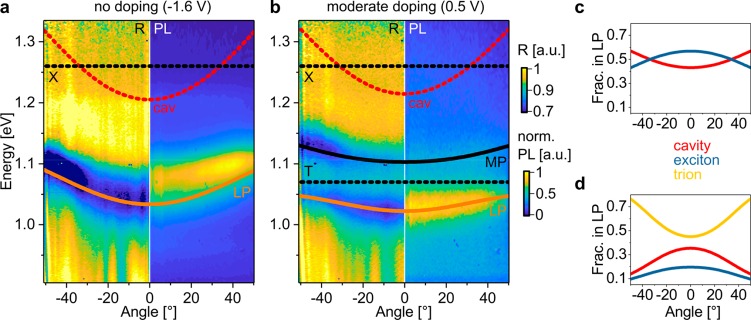

Angle-resolved reflectivity and photoluminescence spectra of the cavity for different applied voltages and doping regimes were recorded using a Fourier-imaging setup, as described previously9 (see Supporting Information). Figure 2a shows the angle-dependent reflectivity (R) and photoluminescence (PL) for TM polarization in the undoped regime. The lower polariton (LP) mode of an exciton-polariton with relatively flat dispersion is evident. Two upper polariton modes above the exciton (MP2, UP) are shown in Figure S3 (Supporting Information). The large energy splitting of around 0.5 eV between LP and UP indicates ultrastrong coupling. For similar measurements on a different sample with different detuning see Figure S4 (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Angle-resolved reflectivity (R, left, negative angles) and photoluminescence (PL, right, positive angles) spectra for TM polarization of the lower polariton branch (LP) in (a) the undoped regime and (b) the moderately hole-doped regime. The latter shows splitting of the LP into a lower LP and a new middle polariton mode (MP). The observed LP (orange solid line) and MP (black solid line) were fitted to the reflectivity spectra (R, left, negative angles) using the coupled oscillator model with the uncoupled modes for the exciton (X, dashed black line), trion (T, dashed black line) and the bare cavity (cav, red dashed line). Calculated fractions of uncoupled modes in the LP for the (c) undoped and (d) moderately doped regime are shown. See Figure S5 (Supporting Information) for fractions of the other polariton modes.

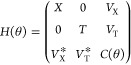

After application of a moderate positive voltage (+0.5 V) and thus hole doping of the (6,5) SWCNTs, the LP splits into two modes below and above the trion energy, forming a lower polariton and a middle polariton (MP), respectively, with a minimum energy splitting of (77 ± 1) meV (see Figure 2b). The presence of positively charged trions and the avoided crossing at the trion energy clearly indicate the formation of trion-exciton-polaritons. Photoluminescence occurs from the new LP closely following the dispersion observed in reflectivity. The modes of the exciton-polariton and trion-exciton-polariton in Figure 2a and b, respectively, can be fitted with the coupled-oscillator model51,52 using the Hamiltonian:

|

1 |

Here X and T are the exciton (1.26 eV) and trion (1.07 eV) energies, respectively. Both modes couple strongly to the cavity mode C with the coupling potentials VX and VT between the cavity mode and the exciton or trion, respectively. No direct coupling between the exciton and trion is assumed. The angular dispersion of the cavity mode in a planar microcavity follows the relation:

| 2 |

with C0 being the cavity mode energy at 0° emission angle. The detuning Δ of the cavity is given by C0 – X. For the exciton-polariton (Figure 2a) in the undoped regime, the trion coupling potential VT was fixed to zero.

The fit of the lower polariton branch of the exciton-polariton in Figure 2a results in an exciton coupling potential VX of (197 ± 8) meV, an effective refractive index neff of (1.94 ± 0.02) and a cavity detuning of Δ = (−55 ± 3) meV. For the trion-exciton-polariton (Figure 2b), the fit yields a trion coupling potential VT of (54 ± 6) meV, in agreement with the observed mode splitting. In comparison to the undoped case, the exciton coupling VX is reduced to (177 ± 9) meV due the reduced excitonic absorbance, similar to previous experiments.45

Figure 2c,d shows the fractions of the uncoupled modes (C, X, T) contributing to the LP mode for the neutral and doped case. These were calculated by projecting the initial eigenstates onto the new polariton states. The LP of the trion-exciton-polariton mostly originates from the strong coupling between the trion and the cavity mode, whereas the exciton contributes less than 20% (see Figures 2d and S5, Supporting Information, for more details). Thus, we refer to the new charged polariton simply as trion-polariton.

The angle dependent photoluminescence spectra reveal that while the total brightness of the PL from the LP in the doped state is reduced compared to the pure exciton-polariton, the relaxation dynamics within the polariton branch apparently change upon doping and coupling to trions. The LP of the exciton-polariton shows maximum emission at large angles for TM and at 0° for TE polarization, as previously observed in a similar system.9 In contrast to that, the LP of the trion-polariton shows maximum emission at 0° for both polarizations (see Supporting Information, Figures S6 and S7), indicating improved polariton relaxation; possibly due to enhanced polariton-polariton18 and trion-polariton scattering. The emission from the LP of the exciton-polariton shows a distinct blue-shift of 30 meV compared to its reflectivity whereas for the trion-polariton this offset is almost negligible (Figure 2a,b). In other systems, blue-shifts of the LP branch ranging between 0.1 to 10 meV are observed at high pump fluences and are often associated with polariton-exciton or polariton-polariton interaction.18,23,53 Considering the low pump fluences used in this experiment, the origin of this blue-shift remains an interesting open question.

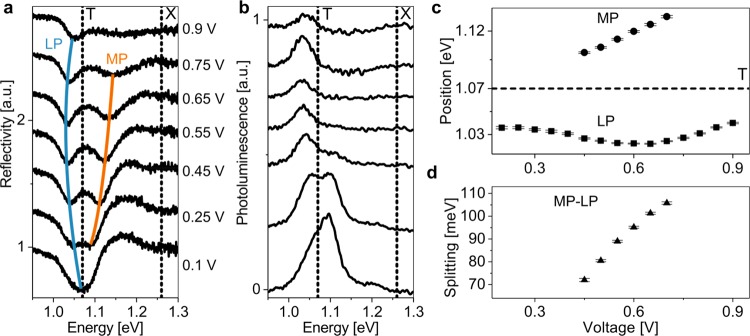

The appearance of the MP can be further illustrated with reflectivity spectra at a fixed angle of 30° (angle of minimal splitting) for different applied voltages from the undoped to the highly doped regime (Figure 3a). At voltages above +0.25 V a clear splitting becomes evident and at a bias of +0.55 V the LP and MP have nearly identical line widths and depths of the reflectance minima. The photoluminescence spectrum (Figure 3b) in the undoped regime (0.1 V) shows a single emission peak above the trion energy (i.e., lower exciton polariton). This peak splits into two (LP and MP of the trion-polariton) as the voltage increases to 0.25 V. At higher positive voltages, only the emission from the LP of the trion-polariton remains. Its intensity is lower compared to the LP of the pure exciton-polariton, probably due to Auger quenching37 and bleaching of the S22-transition, which decreases the laser absorption. The complete angle-dependent reflectivity and photoluminescence spectra for these voltages and for both polarizations are shown in Figures S6 and S7 (Supporting Information).

Figure 3.

(a) Reflectivity and (b) photoluminescence spectra for TM polarization at a fixed angle of 30° for different applied voltages from 0.9 V (top, strongly doped) to 0.1 V (bottom, barely doped). (c) Spectral position of LP and MP at 0° and (d) voltage-dependent splitting between LP and MP at minimal splitting angle (30°).

Figure 3c shows the energetic positions of the LP and MP (at 0°) as a function of voltage in more detail. While the MP blue-shifts nearly linearly with voltage and carrier density, the LP shifts to slightly lower energies due the additional coupling to the trion. For higher voltages, it also blue-shifts, which indicates a decrease of trion and exciton oscillator strength. The broadening of the trion resonance with increasing voltage (see Figures 1c or S2, Supporting Information) also causes broadening of the MP (see Figures S6 and S7, Supporting Information), rendering the coupled oscillator fit unreliable at a bias above +0.7 V. Figure 3d shows the increasing energy splitting between MP and LP as a function of voltage in the experimentally observable strong coupling regime between +0.45 and +0.7 V.

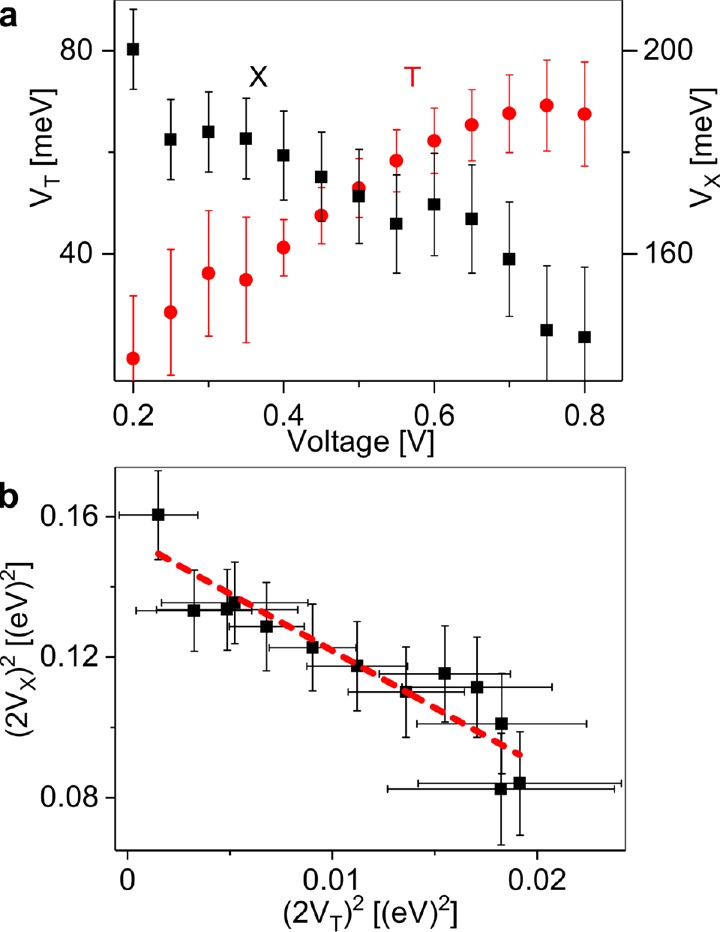

The trion and exciton coupling potentials (VX and VT) in the strong coupling regime were obtained by fitting the coupled oscillator model to the angle resolved reflectance for all applied voltages. Their dependence on voltage is shown in Figure 4a. The trion coupling potential VT increases and the exciton coupling potential VX decreases with increasing positive voltage, that is, hole-doping. This correlation indicates oscillator strength transfer from the exciton to the trion in the moderately hole-doped regime as previously observed in inorganic charged polariton systems.25,54 In order to visualize this transfer more clearly, the squared coupling potentials were plotted versus each other in Figure 4b. As the coupling potential should roughly scale with the square root of the oscillator strength,51 in analogy to a two-level system, a linear correlation further corroborates oscillator strength transfer. The slope in Figure 4b represents the proportionality factor γ between exciton and trion oscillator strength54 (fX and fT, respectively):

| 3 |

Here γ = 3.2 ± 0.8 is larger than one, which means that the summed oscillator strength f = fX + fT is not conserved in this system.

Figure 4.

(a) Voltage-dependent trion (VT, red) and exciton (VX, black) coupling potentials (including error bars) obtained by fitting angle-resolved reflectance data for different applied voltages. (b) Linear correlation between squared exciton and trion coupling potentials in the moderate doping regime, indicating oscillator strength transfer with a slope of γ = 3.2 ± 0.8.

The low mass of trion-polaritons as charged quasiparticles may have consequences for charge transport in microcavities. According to conventional semiconductor theory the carrier mobility is directly proportional to the charge-to-effective-mass ratio and the time between scattering events. For example, the carrier mobility of s-SWCNTs scales with the square of the diameter as a result of the decrease of both the effective mass and the scattering rate with increasing diameter.55,56 Rapaport et al. estimated for trion-polaritons in GaAs/AlAs quantum-well microcavities in the presence of a two-dimensional electron gas that their low mass and thus high charge-to-mass ratio could lead to significantly higher drift velocities in an electrical field.25 To estimate the potential for polariton-enhanced charge transport in s-SWCNTs, we calculated the effective inertial mass (related to wavepacket propagation)57 of the trion-polariton from the dispersion of the LP and derived the theoretical charge-to-mass ratio by taking into account the fraction of the trion charge in the LP using

| 4 |

where e0 is the elementary charge, |αLP,T|2 the trion fraction of the lower polariton and E(k) is the angular energy dispersion of the lower polariton mode. The resulting charge-to-mass ratio at 0° emission angle is about 200× higher than that of an electron or hole in s-SWCNTs56 (see Supporting Information, Figure S8) and remains large, even for nonzero angles.

The simple structure used in our experiments, however, is not suitable for investigating polaritonic transport due to the random nanotube orientation, metallic mirrors and the unwanted effects of any additional bias (e.g., between the gold mirrors) on the doping concentration and trion distribution in the cavity. Nevertheless, a planar source-drain electrode structure as in electrolyte-gated s-SWCNT transistors37 in combination with dielectric mirrors for a cavity perpendicular to the transport direction might be suitable. The necessary concentration of trions in the (6,5) SWCNT film could be fixed by freezing the ionic motion in the iongel at low temperatures or by chemical instead of electrochemical doping. To avoid the problem of hopping between nanotubes in random networks as a bottleneck, short channel transistors with dense aligned films of nanotubes58,59 integrated in a high-quality cavity might be used to observe trion-polariton transport.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we demonstrated voltage-tunable formation of charged polaritons (trion-polaritons) in simple planar microcavities with (6,5) single-walled carbon nanotubes at room temperature. The energy splitting between the lower and middle polariton mode reached 70 to 100 meV. In addition to the observed splitting at moderate doping levels, trion-polariton emission occurred almost exclusively from the lower polariton, which showed a strong trionic character and thus a large fractional charge. Combined with the very low effective mass of the trion-polariton owing to its photonic character the estimated charge-to-mass ratio was up to 200× larger than that of electrons/holes in semiconducting carbon nanotubes. This effect could be potentially utilized for enhanced charge transport in polaritonic devices.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013)/ERC Grant Agreement No. 306298 (EN-LUMINATE). V.L. thanks the DAAD-RISE programme. J.L., M.C.G., and J.Z. thank the Volkswagenstiftung (Grant No. 93404) for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsphotonics.7b01549.

Sample preparation, design, and analysis of reflectance and photoluminescence measurements; absorption spectra of (6,5) nanotube dispersion and film; film absorption spectra for different applied voltages; full reflectance spectra for a neutral nanotube film in a cavity from 0.9 to 1.7 eV; absorbance, reflectivity, photoluminescence, fractions of uncoupled modes for a different hole-doped (6,5) SWNT cavity; calculated fractions of uncoupled modes in polariton modes, angle-dependent reflectance and photoluminescence spectra at different voltages for TE and TM polarization, calculated charge-to-mass ratio of trion-polariton at different voltages (PDF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baranov D. G.; Wersäll M.; Cuadra J.; Antosiewicz T. J.; Shegai T. Novel Nanostructures and Materials for Strong Light–Matter Interactions. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 24–42. 10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbuch C.; Nishioka M.; Ishikawa A.; Arakawa Y. Observation of the Coupled Exciton-Photon Mode Splitting in a Semiconductor Quantum Microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 69, 3314–3317. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.69.3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoine-Vincent N.; Natali F.; Byrne D.; Vasson A.; Disseix P.; Leymarie J.; Leroux M.; Semond F.; Massies J. Observation of Rabi Splitting in a Bulk GaN Microcavity Grown on Silicon. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2003, 68, 153313. 10.1103/PhysRevB.68.153313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zamfirescu M.; Kavokin A.; Gil B.; Malpuech G.; Kaliteevski M. ZnO as a Material Mostly Adapted for the Realization of Room-Temperature Polariton Lasers. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2002, 65, 161205. 10.1103/PhysRevB.65.161205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lidzey D. G.; Bradley D. D. C.; Skolnick M. S.; Virgili T.; Walker S.; Whittaker D. M. Strong Exciton-Photon Coupling in an Organic Semiconductor Microcavity. Nature 1998, 395, 53–55. 10.1038/25692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz T.; Hutchison J. A.; Genet C.; Ebbesen T. W. Reversible Switching of Ultrastrong Light-Molecule Coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 196405. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.196405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.-H.; He Y.; Nurmikko A. V.; Tischler J.; Bulovic V. Exciton-Polariton Dynamics in a Transparent Organic Semiconductor Microcavity. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2004, 69, 235330. 10.1103/PhysRevB.69.235330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kéna-Cohen S.; Davanço M.; Forrest S. R. Strong Exciton-Photon Coupling in an Organic Single Crystal Microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 116401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.116401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf A.; Tropf L.; Zakharko Y.; Zaumseil J.; Gather M. C. Near-Infrared Exciton-Polaritons in Strongly Coupled Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Microcavities. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13078. 10.1038/ncomms13078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Galfsky T.; Sun Z.; Xia F.; Lin E.-c.; Lee Y.-H.; Kéna-Cohen S.; Menon V. M. Strong Light–Matter Coupling in Two-Dimensional Atomic Crystals. Nat. Photonics 2015, 9, 30–34. 10.1038/nphoton.2014.304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flatten L. C.; He Z.; Coles D. M.; Trichet A. A. P.; Powell A. W.; Taylor R. A.; Warner J. H.; Smith J. M. Room-Temperature Exciton-Polaritons with Two-Dimensional WS2. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33134. 10.1038/srep33134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Li S.; Chervy T.; Shalabney A.; Azzini S.; Orgiu E.; Hutchison J. A.; Genet C.; Samorì P.; Ebbesen T. W. Coherent Coupling of WS2 Monolayers with Metallic Photonic Nanostructures at Room Temperature. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 4368–4374. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasprzak J.; Richard M.; Kundermann S.; Baas A.; Jeambrun P.; Keeling J. M. J.; Marchetti F. M.; Szymanska M. H.; Andre R.; Staehli J. L.; Savona V.; Littlewood P. B.; Deveaud B.; Dang L. S. Bose–Einstein Condensation of Exciton Polaritons. Nature 2006, 443, 409–414. 10.1038/nature05131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balili R.; Hartwell V.; Snoke D.; Pfeiffer L.; West K. Bose–Einstein Condensation of Microcavity Polaritons in a Trap. Science 2007, 316, 1007–1010. 10.1126/science.1140990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amo A.; Lefrere J.; Pigeon S.; Adrados C.; Ciuti C.; Carusotto I.; Houdre R.; Giacobino E.; Bramati A. Superfluidity of Polaritons in Semiconductor Microcavities. Nat. Phys. 2009, 5, 805–810. 10.1038/nphys1364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lagoudakis K. G.; Wouters M.; Richard M.; Baas A.; Carusotto I.; Andre R.; Dang L. S.; Deveaud-Pledran B. Quantized Vortices in an Exciton-Polariton Condensate. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 706–710. 10.1038/nphys1051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plumhof J. D.; Stöferle T.; Mai L.; Scherf U.; Mahrt R. F. Room-Temperature Bose–Einstein Condensation of Cavity Exciton–Polaritons in a Polymer. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 247–252. 10.1038/nmat3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daskalakis K. S.; Maier S. A.; Murray R.; Kéna-Cohen S. Nonlinear Interactions in an Organic Polariton Condensate. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 271–278. 10.1038/nmat3874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerario G.; Fieramosca A.; Barachati F.; Ballarini D.; Daskalakis K. S.; Dominici L.; De Giorgi M.; Maier S. A.; Gigli G.; Kena-Cohen S.; Sanvitto D. Room-Temperature Superfluidity in a Polariton Condensate. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 837–841. 10.1038/nphys4147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrovska N.; Matuszewski M.; Daskalakis K. S.; Maier S. A.; Kéna-Cohen S. Dynamical Instability of a Nonequilibrium Exciton-Polariton Condensate. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 111–118. 10.1021/acsphotonics.7b00283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kena-Cohen S.; Forrest S. R. Room-Temperature Polariton Lasing in an Organic Single-Crystal Microcavity. Nat. Photonics 2010, 4, 371–375. 10.1038/nphoton.2010.86. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su R.; Diederichs C.; Wang J.; Liew T. C. H.; Zhao J.; Liu S.; Xu W.; Chen Z.; Xiong Q. Room-Temperature Polariton Lasing in All-Inorganic Perovskite Nanoplatelets. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 3982–3988. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich C. P.; Steude A.; Tropf L.; Schubert M.; Kronenberg N. M.; Ostermann K.; Höfling S.; Gather M. C. An Exciton-Polariton Laser Based on Biologically Produced Fluorescent Protein. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600666. 10.1126/sciadv.1600666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C.; Rahimi-Iman A.; Kim N. Y.; Fischer J.; Savenko I. G.; Amthor M.; Lermer M.; Wolf A.; Worschech L.; Kulakovskii V. D.; Shelykh I. A.; Kamp M.; Reitzenstein S.; Forchel A.; Yamamoto Y.; Hofling S. An Electrically Pumped Polariton Laser. Nature 2013, 497, 348–352. 10.1038/nature12036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport R.; Cohen E.; Ron A.; Linder E.; Pfeiffer L. N. Negatively Charged Polaritons in a Semiconductor Microcavity. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2001, 63, 235310. 10.1103/PhysRevB.63.235310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C.-Y.; Dhanker R.; Gray C. L.; Mukhopadhyay S.; Kennehan E. R.; Asbury J. B.; Sokolov A.; Giebink N. C. Charged Polaron Polaritons in an Organic Semiconductor Microcavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 017402. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.017402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein G.; Shtrikman H.; Bar-Joseph I. Negatively and Positively Charged Excitons in GaAs/AlxGa1-XAs Quantum Wells. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1996, 53, R1709–R1712. 10.1103/PhysRevB.53.R1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka S.; Wuester W.; Haupt F.; Faelt S.; Wegscheider W.; Imamoglu A. Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics with Many-Body States of a Two-Dimensional Electron Gas. Science 2014, 346, 332–335. 10.1126/science.1258595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajoni D.; Perrin M.; Senellart P.; Lemaître A.; Sermage B.; Bloch J. Dynamics of Microcavity Polaritons in the Presence of an Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2006, 73, 205344. 10.1103/PhysRevB.73.205344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sidler M.; Back P.; Cotlet O.; Srivastava A.; Fink T.; Kroner M.; Demler E.; Imamoglu A. Fermi Polaron-Polaritons in Charge-Tunable Atomically Thin Semiconductors. Nat. Phys. 2016, 13, 255–261. 10.1038/nphys3949. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhara S.; Chakraborty C.; Goodfellow K. M.; Qiu L.; O’Loughlin T. A.; Wicks G. W.; Bhattacharjee S.; Vamivakas A. N. Anomalous Dispersion of Microcavity Trion-Polaritons. Nat. Phys. 2017, 14, 130–133. 10.1038/nphys4303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deilmann T.; Rohlfing M. Huge Trionic Effects in Graphene Nanoribbons. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 6833–6837. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b03111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak K. F.; He K.; Lee C.; Lee G. H.; Hone J.; Heinz T. F.; Shan J. Tightly Bound Trions in Monolayer MoS2. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 207–211. 10.1038/nmat3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouri S.; Miyauchi Y.; Matsuda K. Tunable Photoluminescence of Monolayer MoS2via Chemical Doping. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 5944–5948. 10.1021/nl403036h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga R.; Matsuda K.; Kanemitsu Y. Observation of Charged Excitons in Hole-Doped Carbon Nanotubes Using Photoluminescence and Absorption Spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 037404. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.037404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. S.; Hirana Y.; Mouri S.; Miyauchi Y.; Nakashima N.; Matsuda K. Observation of Negative and Positive Trions in the Electrochemically Carrier-Doped Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14461–14466. 10.1021/ja304282j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubka F.; Grimm S. B.; Zakharko Y.; Gannott F.; Zaumseil J. Trion Electroluminescence from Semiconducting Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 8477–8486. 10.1021/nn503046y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckstein K. H.; Hartleb H.; Achsnich M. M.; Schöppler F.; Hertel T. Localized Charges Control Exciton Energetics and Energy Dissipation in Doped Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 10401–10408. 10.1021/acsnano.7b05543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimkin D. K.; MacDonald A. H. Many-Body Theory of Trion Absorption Features in Two-Dimensional Semiconductors. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2017, 95, 035417. 10.1103/PhysRevB.95.035417. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schießl S. P.; Rother M.; Lüttgens J.; Zaumseil J. Extracting the Field-Effect Mobilities of Random Semiconducting Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube Networks: A Critical Comparison of Methods. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 111, 193301. 10.1063/1.5006877. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M.; Popert A.; Kato Y. K. Gate-Voltage Induced Trions in Suspended Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2016, 93, 041402. 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.041402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graf A.; Zakharko Y.; Schießl S. P.; Backes C.; Pfohl M.; Flavel B. S.; Zaumseil J. Large Scale, Selective Dispersion of Long Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes with High Photoluminescence Quantum Yield by Shear Force Mixing. Carbon 2016, 105, 593–599. 10.1016/j.carbon.2016.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos S. M.; Yuma B.; Berciaud S.; Shaver J.; Gallart M.; Gilliot P.; Cognet L.; Lounis B. All-Optical Trion Generation in Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 187401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.187401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf A.; Murawski C.; Zakharko Y.; Zaumseil J.; Gather M. C. Infrared Organic Light-Emitting Diodes with Carbon Nanotube Emitters. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706711. 10.1002/adma.201706711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf A.; Held M.; Zakharko Y.; Tropf L.; Gather M. C.; Zaumseil J. Electrical Pumping and Tuning of Exciton-Polaritons in Carbon Nanotube Microcavities. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 911–917. 10.1038/nmat4940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger F. J.; Higgins T. M.; Rother M.; Graf A.; Zakharko Y.; Allard S.; Matthiesen M.; Gotthardt J. M.; Scherf U.; Zaumseil J. From Broadband to Electrochromic Notch Filters with Printed Monochiral Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 11135–11142. 10.1021/acsami.8b00643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre C. M.; Levesque P. L.; Paillet M.; Lapointe F.; St-Antoine B. C.; Desjardins P.; Martel R. The Role of the Oxygen/Water Redox Couple in Suppressing Electron Conduction in Field-Effect Transistors. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 3087–3091. 10.1002/adma.200900550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn J. L.; Holt J. M.; Irurzun V. M.; Resasco D. E.; Rumbles G. Confirmation of K-Momentum Dark Exciton Vibronic Sidebands Using 13c-Labeled, Highly Enriched (6,5) Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1398–1403. 10.1021/nl204072x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartleb H.; Späth F.; Hertel T. Evidence for Strong Electronic Correlations in the Spectra of Gate-Doped Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 10461–10470. 10.1021/acsnano.5b04707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spataru C. D.; Léonard F. Tunable Band Gaps and Excitons in Doped Semiconducting Carbon Nanotubes Made Possible by Acoustic Plasmons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 177402. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.177402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta E. A.; Roma P. M. S. Determination of Oscillator Strength of Confined Excitons in a Semiconductor Microcavity. Condens. Matter Phys. 2014, 17, 23702. 10.5488/CMP.17.23702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y.; Tassone F.; Cao H.. Semiconductor Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics; Springer-Verlag: Berlin; Heidelberg, 2000; Vol. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y.; Yoon Y.; Steger M.; Liu G.; Pfeiffer L. N.; West K.; Snoke D. W.; Nelson K. A. Direct Measurement of Polariton-Polariton Interaction Strength. Nat. Phys. 2017, 13, 870–875. 10.1038/nphys4148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunhes T.; André R.; Arnoult A.; Cibert J.; Wasiela A. Oscillator Strength Transfer from X to X+ in a CdTe Quantum-Well Microcavity. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 1999, 60, 11568–11571. 10.1103/PhysRevB.60.11568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biercuk M. J.; Ilani S.; Marcus C. M.; McEuen P. L. Electrical Transport in Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Top. Appl. Phys. 2007, 111, 455–493. 10.1007/978-3-540-72865-8_15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G. L.; Bagayoko D.; Yang L. Effective Masses of Charge Carriers in Selected Symmorphic and Nonsymmorphic Carbon Nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2004, 69, 245416. 10.1103/PhysRevB.69.245416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colas D.; Laussy F. P. Self-Interfering Wave Packets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 116, 026401. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.026401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady G. J.; Way A. J.; Safron N. S.; Evensen H. T.; Gopalan P.; Arnold M. S. Quasi-Ballistic Carbon Nanotube Array Transistors with Current Density Exceeding Si and GaAs. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1601240. 10.1126/sciadv.1601240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X.; Gao W.; Xie L.; Li B.; Zhang Q.; Lei S.; Robinson J. M.; Hároz E. H.; Doorn S. K.; Wang W.; Vajtai R.; Ajayan P. M.; Adams W. W.; Hauge R. H.; Kono J. Wafer-Scale Monodomain Films of Spontaneously Aligned Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2016, 11, 633–638. 10.1038/nnano.2016.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.