Abstract

Advances in technology and computing now permit the high-throughput analysis of multiple domains of biologic information, including the genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome. These omics approaches, particularly comprehensive analysis of the genome, have catalyzed major discoveries in science and medicine, including in nephrology. However, they also generate large, complex data sets that can be difficult to synthesize from a clinical perspective. This article seeks to provide an overview that makes omics technologies relevant to the practicing nephrologist, framing these tools as an extension of how we approach patient care in the clinic. More specifically, omics technologies reinforce the impact genetic mutations can have on a range of kidney disorders; expand the catalog of uremic molecules that accumulate in blood with renal failure; enhance our ability to scrutinize urine beyond urinalysis for insight on renal pathology; and enable more extensive characterization of kidney tissue when a biopsy is performed. Although assay methodologies vary widely, all omics technologies share a common conceptual framework that embraces unbiased discovery at the molecular level. Ultimately, the application of these technologies seeks to elucidate a more mechanistic and individualized approach to the diagnosis and treatment of human disease.

Keywords: Omics, Genomics, Transcriptomics, Metabolomics, Proteomics, Systems biology, urinomics, analytic methods, nephrology research, translational research, rev

Introduction

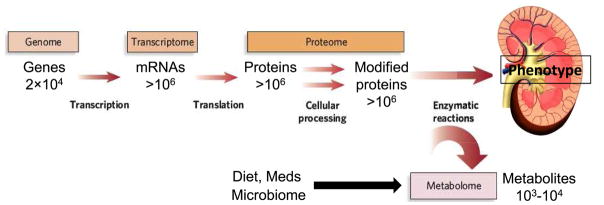

Although it has undergone some revision, Francis Crick’s “central dogma” of molecular biology remains the archetype for the flow of information in biological systems, namely that DNA makes RNA and RNA makes proteins. Some proteins, for example enzymes and transporters, then modulate metabolites. Omics approaches aim to provide comprehensive analysis of a given set of molecules, and include genomics (DNA), transcriptomics (RNA), proteomics (proteins), and metabolomics (metabolites).1,2 This Perspective provides a brief overview of these methodologies, with examples in nephrology research that outline their potential to advance clinical care.

Omics Approaches

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual inter-relationship of omics approaches, highlighting the approximate number of entities (e.g. genes, transcripts, proteins, or metabolites) within each domain, and Table 1 outlines relevant analytical techniques. For comprehensive descriptions of underlying methods, the reader is referred to dedicated reviews.

Figure 1. The flow of biological information from the genome to transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome.

The estimated number of each type of molecule in a typical cell is indicated. The epigenome, not shown, resides conceptually between the genome and transcriptome; also not shown are various non-coding RNAs that are not transcribed into protein but are increasingly recognized to have important biological roles. Modified from Gertzen e al.58 with permission of the copyright holder, Springer-Nature.

Table 1.

Overview of Omics Methodologies

| Methodology | Omics Approaches | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Microarray | Genomics (GWAS); microarray-based Transcriptomics | Relies on noncovalent bonding between DNA strands that are complementary. DNA sequences of interest (known as probes or oligos) are arranged on a surface. For genomics studies, probes are designed to be specific for SNPs across the genome. For transcriptomics, probes are designed to be specific for different gene transcripts. Experimental samples containing target DNA or cDNA (mRNA that has been reverse transcribed) are hybridized to the microarray and then a variety of techniques can be used to quantitate probe-target capture. |

| Next-generation sequencing | Genomics; RNA-seq– based transcriptomics | Methods vary, but a common theme is that many sequencing reactions of random DNA segments are performed in parallel, and enzymatic reactions are used to determine nucleotide sequence in real time (e.g. using luminescence or fluorescence), rather than requiring gel electrophoresis as with traditional Sanger sequencing. Computational methods align and merge data from the multiple, parallel reads in order to reconstruct the original full-length sequences. |

| Mass spectrometry | Proteomics; metabolomics | Resolves molecules on the basis of their mass, or more precisely, their mass-to-charge ratio following ionization. Usually proteins first undergo proteolytic cleavage and are separated (by hydrophobicity and charge) by capillary electrophoresis, liquid chromatography, or gas chromatography. |

| Affinity-based assay | Proteomics | Traditionally, refers to multiplexing antibodies of known specificity on an array to simultaneously measure multiple proteins. More recently, affinity reagents other than antibodies (such as oligonucleotides) have increased the breadth and throughput of these approaches. |

| NMR spectroscopy | Metabolomics | Utilizes magnetic properties of select atomic nuclei (e.g. 1H, 13C, or 31P) to determine the structure and abundance of metabolites. |

Abbreviations: NMR, Nuclear magnetic resonance; GWAS, genome-wide association studies; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; cDNA, complementary DNA; mRNA, messenger RNA

Genomics

The human genome is comprised of approximately 3 billion DNA base pairs, <2% of which are dedicated to coding approximately 20,000 genes. Strategies to analyze the genome in human studies vary.3,4 For genome wide association studies (GWAS) that can span many thousands of individuals, the most common approach has been to use DNA microarrays to genotype up to ~1 million nucleotides at pre-specified positions in the genome known to vary across individuals (also known as single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs).5 Using a case-control approach, GWAS aim to identify SNPs that are significantly enriched among individuals with a given disease compared to unaffected controls. These studies causally implicate specific genomic regions in disease pathogenesis, but do not necessarily identify the causal genetic alterations. Instead, the identified SNP is assumed to be in close proximity with the causal alteration in DNA sequence, which may not have been among the pre-specified SNPs included on the DNA microarray. An alternative to microarrays is to sequence entire genomes (or key portions of the genome, such as all coding genes), an approach enabled by the development of high-throughput DNA sequencing techniques, often referred to as next-generation sequencing (NGS).6 These methods provide more comprehensive information about each individual’s genome, including rare mutations (DNA microarrays are usually restricted to relatively common SNPs). However, these methods are more costly and computationally demanding and thus are restricted to relatively smaller sample sizes.

Transcriptomics

Given the structural similarities between DNA and RNA, methods for analyzing the genome and transcriptome are similar. As with genomics, transcriptomic capabilities have evolved over time from microarray-based quantitation of pre-specified transcripts to comprehensive analysis of all transcribed RNA using NGS, often termed RNA sequencing or RNA-Seq. Traditional microarray approaches generally focus on protein-coding messenger RNA (mRNA).7 Comprehensive sequencing with RNA-Seq can provide more granular information, differentiating amongst mRNA isoforms or splice variants.8,9 In addition, NGS-based methods have revealed significant expression of non-coding RNAs—RNAs that do not encode proteins—such as microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs that have diverse effects on regulating gene expression.

Proteomics

Proteins perform most of the actual work in cells and tissues, and thus span an enormous diversity of form and function as structural proteins, transcription factors, receptors, antibodies, hormones, ion and solute transporters, and enzymes. To add to this complexity, measuring the relative abundance of proteins provides incomplete information on the proteome. Alternative splice variants from a single gene can yield several distinct proteins and post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation and ubiquitination have a profound impact on protein localization, activity, and turnover. In addition, some proteins require specific protein-protein interactions or expression in specific cellular compartments to function properly. At present, different analytical techniques, along with dedicated bioinformatics methods, are required to assess these different facets of the proteome.10–12

Metabolomics

The metabolome is the global collection of small molecules, typically <1500 Daltons, including carbohydrates, amino acids, organic acids, and lipids.13–15 Downstream of transcription and translation, metabolite levels reflect gene, transcript, and protein abundance and function, thus providing information that is both complementary and in some cases summative of these other domains. Decades of research in metabolism have placed many metabolites within defined biochemical pathways, providing a framework for data interpretation. In addition, the metabolome includes inputs from diet, environment, and the microbiome, integrating endogenous and exogenous sources of biological variation.

Other

In addition to the methods described above, epigenomics is the comprehensive study of epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation and histone modification, reversible alterations that modulate gene expression; thus epigenomics resides conceptually between genomics and transcriptomics.16,17 Lipidomics is a specialized area within metabolomics dedicated to the analysis of lipids. Microbiomics is the study of the genomes of microorganisms that reside on and within the human body, such as in the gastrointestinal tract.18

Considerations in Using Omics approaches

Several practical observations warrant mention. First, genomics stands apart because DNA sequence is static and identical throughout the body (excluding tumors); thus, DNA amplified from isolated white blood cells or epithelial cells in saliva yields comprehensive and representative data. By contrast, RNA, protein, and metabolite levels change over time, in response to different stimuli, and across cell types and tissues such that the timing, conditions, and site of sampling have to be tailored to the question of interest. Second, genomic DNA functions exclusively inside cells, whereas proteins and metabolites function both within and outside cells, including blood and urine. Thus, these latter technologies are often employed for biomarker discovery. RNA is primarily intracellular, but some microRNAs have biological functions in circulation and mRNA can be detected within exosomes, cell-derived vesicles released into blood and urine. Third, although tools continue to improve, at present genomics and transcriptomics are more robust and comprehensive than proteomics and metabolomics. Incomplete coverage and heterogeneity of data quality across the proteome and metabolome remain important challenges.

Given the multiplicity of measurements, all omics techniques generate large data sets that require specialized approaches to data storage, management, reduction, and analysis. As these considerations are largely beyond the scope of this article, only select themes are noted here. For example, across all methodologies, rigorous quality controls are required to cull low-quality or potentially erroneous results. Further, because many measurements in a given omics data set are related—for example enzymes or metabolites along a single biochemical pathway—statistical approaches have been developed to account for inter-correlations, to identify clusters of interest, and to interpret results in the context of pathways. Finally, all omics analyses require statistical adjustments for multiple hypothesis testing to minimize the risk of false positive findings – for genomics, a common standard of ‘genome-wide significance’ is a p-value < 5 x 10−8.

Omics and Clinical Nephrology

Taken together, the proliferation of omics approaches provides powerful tools to study human disease, as well as a bewildering surfeit of data and jargon. Rather than getting mired in this complexity, a useful approach is to view these technologies from the perspective of a Nephrologist, as a natural extension of current clinical perspectives and practice. As the following examples demonstrate, one or a subset of omics approaches may be most applicable depending on the specific clinical context—to date, however, only genomics approaches have progressed to clinical practice, whereas other omics approaches are presently restricted to research applications.

Understanding inherited predispositions to kidney disease

Monogeneic disorders, where mutations in a single gene are sufficient to cause disease, are frequently encountered in Nephrology, with examples ranging from steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome (SRNS) or congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) in children, to Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD), Alport syndrome, Primary hyperoxaluria, and Gitelman syndrome.19 For relatively common diseases such as ADPKD and Alport syndrome, targeted sequencing of the relevant genes is routinely performed in clinical practice. Although traditional linkage analyses and candidate-gene approaches were used to identify the causal gene in most of these diseases, genomics has made a major impact over the past decade, significantly accelerating the pace of discovery for less common monogeneic disorders. For example, ~30 different genes have now been shown to cause SRNS.20

In addition to providing fundamental insight on disease biology, the identification of disease-causing mutations can also deliver immediate clinical value. For example, recognition that a patient’s nephrotic syndrome is due to a genetic mutation can spare the patient unnecessary exposure to immunosuppression. By contrast, in a small subset of SRNS caused by mutations in coenzyme Q10 biosynthesis, patients can be treated with coenzyme Q10 supplementation.21 Although the yield of genetic testing is higher with childhood diseases and/or pedigrees with multiple affected family members, it may also reveal de novo mutations and provide unexpected genetic diagnoses in some confounding cases.22 Even when a genetic diagnosis does not have treatment implications, knowledge of genetic etiology can provide affected patients with prognostic information and facilitate genetic counseling about future pregnancies or the risks of living kidney donation. Across all of these applications, it is important to note that genomics analyses may also reveal genetic mutations of unknown significance—therefore, interpretation of genetic testing, including commercially available genetic panels, should be performed by someone with expertise in clinical genetics.

The impact of genomics in Nephrology has not been restricted to monogeneic disorders. Two studies identified strong associations between select SNPs and the risk of idiopathic and HIV-associated FSGS23 and non-diabetic ESRD among African Americans.24 Subsequent work showed that the actual causal alterations in DNA sequence (or ‘variants’) driving this risk signal were in the gene APOL1. Individuals with two risk alleles (one risk variant on each chromosome) have >10 fold risk of FSGS or hypertensive ESRD, but having two risk variants is not sufficient to cause disease--other genetic and environmental factors are required.25 Ten to 15% of African Americans have two risk alleles, a frequency explained by the fact that these variants enhance APOL1-mediated killing of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, the cause of African sleeping sickness.26 The large impact of APOL1 variants on kidney disease risk is unique; GWAS has identified many other common variants associated with CKD, but these confer much smaller increments of risk (otherwise, negative selection pressure would have reduced their population frequency).27 Important questions remain unanswered, such as the mechanism by which APOL1 risk variants lead to kidney disease. How knowledge of APOL1 genotype should modify clinical care is also uncertain, for example when advising individual with two risk variants about kidney donation.

Expanding the catalog of solutes that accumulate with kidney disease

The uremic illness is a thoroughly acquired disease state—it arises with chronic kidney failure of any etiology and is cured by restoration of renal clearance following kidney transplantation. As such, the study of uremia may be relatively sidelined from the causal inferences enabled by genomics. By contrast, metabolomics is an ideal tool for understanding which circulating small molecules are retained when kidneys fail. Indeed, recent metabolomics studies have identified dozens of novel uremic solutes.28–31 Many of these metabolites are derived from diet or gut microbes, underscoring the specific capability of metabolomics to integrate both endogenous and exogenous inputs. However, the fundamental question of which solutes are toxic remains unanswered. One approach has been to prioritize uremic metabolites that predict adverse clinical outcomes in large ESRD cohorts. For example, elevated levels of p-cresol sulfate, indoxyl sulfate, asymmetric dimethylarginine, and trimethylamine-N-oxide have been associated with mortality in some, but not all studies to date.32–35 The study of metabolites in relation to uremic symptoms has received much less attention than mortality, in part because of the challenge of reliably quantifying symptom burden.36 Ultimately, improved understanding of which solutes are toxic and why they are toxic is required to improve treatment approaches for uremia.

Nephrologists also think about the retention of small molecules in earlier stages of renal failure. Indeed, metabolite (creatinine and urea), and to a lesser extent peptide (cystatin C), markers of glomerular filtration are the most common means to detect and monitor CKD. However, the kidneys’ impact on circulating metabolites is heterogeneous, subsuming not just filtration, but also reabsorption, secretion, and metabolism. With kidney failure, loss of these functions results in relative levels of solute accumulation that may significantly exceed the increase in filtration markers, particularly for molecules that rely on tubular secretion for clearance.37 Thus, clinical biomarker studies that utilize metabolomics or proteomics can be confounded by baseline differences in underlying kidney function, a challenge that is not completely resolved by statistical adjustments for eGFR.

Enhancing the diagnostic and prognostic value of urinalysis

Perhaps no test is more fundamental to the practice of Nephrology than urinalysis, as the presence or absence of cells, proteins, metabolites, and electrolytes provide important clues about intra-renal processes. Table 2 provides representative examples of how omics methodologies have been used to interrogate urine. Proteomics has been utilized most extensively, with studies demonstrating the discovery and validation of urinary biomarkers in CKD, AKI, glomerular disease, ADPKD and beyond. From a biomarker perspective, peptides (amino acid chains of about 2 to 50 residues in length) have some advantages over full-length proteins, as they undergo glomerular filtration and their measurement is more reproducible.38 Combining many peptides or proteins into a panel of markers may improve performance in the clinic, whereas more individualized consideration of molecules or molecular pathways provides insight on underlying biological processes such as fibrosis, coagulation, and inflammation.39,40 Because the kidney plays a fundamental role in the clearance of many metabolites, urinary metabolomics has also been informative, demonstrating significant alterations across different stages and etiologies of CKD. Transcriptomics has been performed on mRNA extracted from cell pellets following centrifugation of urine samples, as well as from urine exosomes (cell-derived vesicles).

Table 2.

Representative Omics Studies of Urine in Kidney Disease

| Omics Type | Analyte | Potential Clinical Relevance* |

|---|---|---|

| Proteomics | Panel of 273 urine peptides | Prediction of CKD progression that outperforms measurement of albuminuria39 |

| Urine peptides | Prediction of ESRD among fetuses with bilateral CAKUT49 | |

| Bioinformatic integration of urine proteomics data across several studies | Biological insight, i.e. demonstration of enrichment of several processes related to wound healing in diabetic nephropathy40 | |

| Urine YKL-40 | Marker of delayed graft function that may have a functional role in tubular cell apoptosis50 | |

| Proteins such as Aquaporin 2, Polycystin 1, Uromodulin, and NKCC2 2 in urine exosomes | Urine-based diagnosis of genetic disorders that result in absent or altered protein expression in the kidney51,52 | |

| Metabolomics | Paired examination of urine and plasma metabolites | Differentiation between reduced urinary clearance and systemic overproduction for metabolites that are increased in CKD plasma53 |

| Urine organic acids | Demonstration of decreased kidney mitochondrial function in diabetic CKD54 | |

| Urine glycine | Prediction of new onset of CKD55 | |

| Transcriptomics | Urine cellular CD3ε and IP-10 transcripts, and 18S rRNA | Diagnosis and prognostication of acute cellular rejection56 |

| microRNAs from urine exosomes | Identification of incipient diabetic nephropathy57 |

All of these examples are research applications at present

Abbreviations and definitions: CKD, chronic kidney disease; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; NKCC2, sodium/potassium/chloride cotransporter 2; 18S rRNA, a portion of the ribosomal RNA determined by the characteristics of its isolation by ultracentrifugration rate (the S refers to sedimentation rate); IP-10, inducible protein 10; YKL-40, chitinase-3-like protein 1.

As with the interpretation for circulating molecules in blood, urine omics analyses should remain anchored around basic principles of renal physiology. For example, Nephrologists often consider the magnitude and type of proteinuria (albumin versus non-albumin) to infer tubular versus glomerular pathology. Glucose is a metabolite widely assessed in urine in clinical practice, and glucosuria can occur either because blood levels exceed tubular reabsorptive capacity or because of impaired tubular function. The results of omics analyses require the same careful interpretation—whether to attribute the presence of select molecules in urine to increased levels in the blood, increased passage across the glomerular filtration barrier, impaired tubular reabsorption, or release from damaged renal cells is often unclear and depends on both molecule size and the renal health of the study population. For molecules released from kidney tissue, the nephron segment of origin may be uncertain, although public data atlases can provide clues for localization.41,42 From a technical standpoint, the wide range of urinary dilution and concentration can present analytical challenges and needs to be accounted for in data analysis.

Enabling molecular characterization of kidney biopsy tissue

When non-invasive evaluation is not sufficient, Nephrologists gain enormous insight from direct examination of tissue obtained by biopsy. Histopathology can specify the affected nephron compartment(s), assess inflammation and fibrosis, and characterize deposits and immune complexes. Omics applications can further augment the value of kidney biopsy. As cited in Table 2, transcriptomics analyses of renal allograft biopsies have identified mRNA biomarkers of acute rejection which were then able to be measured in urinary cell pellets. In a separate study, a transcriptomics analysis of kidney biopsy samples found that renal expression of epidermal growth factor (EGF) mRNA correlates positively with eGFR. In turn, urine levels of EGF protein correlate with tissue EGF mRNA, cross-sectional eGFR, and the rate of subsequent eGFR loss.43 In addition to serving as a springboard for biomarker discovery, kidney tissue profiling has the potential to identify new treatment targets. For example, transcriptomics performed on kidney tissue from patients and mice with diabetic nephropathy highlighted increased JAK-STAT signaling as a common feature.44 Subsequently, a Phase 2 study of a selective JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor was conducted in 129 patients with diabetic nephropathy, demonstrating lower urine albumin-creatinine ratio at 3 and 6 months as well as a reduction in some inflammatory cytokines.45

For kidney biopsies, most omics analyses to date have been performed on whole tissue extracts. In these cases, a given gene product may be enriched either because it is overexpressed or because of an increase in the number of cells expressing that gene, as might occur with infiltrating inflammatory cells. Some techniques are available to address, at least partially, the heterogeneous and dynamic cellular composition of renal tissue. For example, laser microdissection can separate specific compartments prior to analysis.46 This approach has been used for proteomic analysis of glomerular deposits in patients with amyloidosis, fibrillary GN, and immunotactoid glomerulopathy,47 and to compare the glomerulus-specific proteome in diabetic nephropathy, lupus nephritis, and normal controls.48 Thus, omics profiling can be aligned with the structural resolution of histopathology, enhancing its potential to yield mechanistic insights.

Summary and Perspective

As the most mature field, genomics has already made a large impact on clinical practice, defining the specific mutations responsible for select monogeneic diseases and explaining at least some of the racial disparity in renal outcomes across ethnic groups. Although in a less advanced stage of clinical development, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have demonstrated promise for the study of blood, urine, and kidney tissue across a spectrum of renal diseases. Intertwined with these studies is the goal to highlight subsets of patients at greatest risk who might benefit most from treatment or inclusion in research studies, to improve understanding of disease mechanisms, and to identify new therapeutic targets. Even as increasingly sophisticated analytical and computational tools are developed for achieving these goals, an understanding of age-old principles in renal physiology remains fundamental to sound data interpretation. For important molecules highlighted by omics approaches, measurements in the clinic will likely be made using dedicated (non-omics) assays, increasing precision and reducing cost.

Although omics approaches have different strengths and weaknesses and techniques continue to evolve, they share a common mindset. Namely, human disease is complex and we are not particularly good at guessing which genes, transcripts, proteins, and metabolites are most important. Comprehensive profiling of these domains acknowledges this complexity. Further, omics approaches presuppose that detailed molecular information about a patient’s genes, blood or urine composition, or kidney tissue will provide more mechanistic and individualized insights. Taken together, omics technologies embrace an unbiased approach to study human disease, and have the potential to expand the Nephrologist’s diagnostic and therapeutic armamentarium.

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr Rhee received support from NIH award U01DK060990.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Rhee declares that he has no relevant financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.He JC, Chuang PY, Ma'ayan A, Iyengar R. Systems biology of kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2012;81(1):22–39. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanna MH, Dalla Gassa A, Mayer G, et al. The nephrologist of tomorrow: towards a kidney-omic future. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(3):393–404. doi: 10.1007/s00467-016-3357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keller BJ, Martini S, Sedor JR, Kretzler M. A systems view of genetics in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012;81(1):14–21. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heather JM, Chain B. The sequence of sequencers: The history of sequencing DNA. Genomics. 2016;107(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirschhorn JN, Daly MJ. Genome–wide association studies for common diseases and complex traits. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(2):95–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koboldt DC, Steinberg KM, Larson DE, Wilson RK, Mardis ER. The next-generation sequencing revolution and its impact on genomics. Cell. 2013;155(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulze A, Downward J. Navigating gene expression using microarrays--a technology review. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3(8):E190–195. doi: 10.1038/35087138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ozsolak F, Milos PM. RNA sequencing: advances, challenges and opportunities. Nature reviews Genetics. 2011;12(2):87–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mimura I, Kanki Y, Kodama T, Nangaku M. Revolution of nephrology research by deep sequencing: ChIP-seq and RNA-seq. Kidney Int. 2014;85(1):31–38. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 2003;422(6928):198–207. doi: 10.1038/nature01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mischak H, Delles C, Vlahou A, Vanholder R. Proteomic biomarkers in kidney disease: issues in development and implementation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(4):221–232. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith JG, Gerszten RE. Emerging Affinity-Based Proteomic Technologies for Large-Scale Plasma Profiling in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2017;135(17):1651–1664. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalim S, Rhee EP. An overview of renal metabolomics. Kidney Int. 2017;91(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sas KM, Karnovsky A, Michailidis G, Pennathur S. Metabolomics and diabetes: analytical and computational approaches. Diabetes. 2015;64(3):718–732. doi: 10.2337/db14-0509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy MA, Natarajan R. Recent developments in epigenetics of acute and chronic kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2015;88(2):250–261. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Susztak K. Understanding the epigenetic syntax for the genetic alphabet in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(1):10–17. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramezani A, Raj DS. The gut microbiome, kidney disease, and targeted interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(4):657–670. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hildebrandt F. Genetic kidney diseases. Lancet. 2010 Apr 10;375(9722):1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60236-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovric S, Ashraf S, Tan W, Hildebrandt F. Genetic testing in steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome: when and how? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(11):1802–1813. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desbats MA, Lunardi G, Doimo M, Trevisson E, Salviati L. Genetic bases and clinical manifestations of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ 10) deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2015;38(1):145–156. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9749-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakash S, Gharavi AG. Diagnosing kidney disease in the genetic era. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24(4):380–387. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kopp JB, Smith MW, Nelson GW, et al. MYH9 is a major-effect risk gene for focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1175–1184. doi: 10.1038/ng.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, et al. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedman DJ, Pollak MR. Genetics of kidney failure and the evolving story of APOL1. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(9):3367–3374. doi: 10.1172/JCI46263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329(5993):841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1193032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kottgen A, Pattaro C, Boger CA, et al. New loci associated with kidney function and chronic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42(5):376–384. doi: 10.1038/ng.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato E, Kohno M, Yamamoto M, Fujisawa T, Fujiwara K, Tanaka N. Metabolomic analysis of human plasma from haemodialysis patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 2011;41(3):241–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rhee EP, Souza A, Farrell L, et al. Metabolite profiling identifies markers of uremia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(6):1041–1051. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009111132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kikuchi K, Itoh Y, Tateoka R, Ezawa A, Murakami K, Niwa T. Metabolomic analysis of uremic toxins by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2010;878(20):1662–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka H, Sirich TL, Plummer NS, Weaver DS, Meyer TW. An Enlarged Profile of Uremic Solutes. PloS One. 2015;10(8):e0135657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafi T, Meyer TW, Hostetter TH, et al. Free Levels of Selected Organic Solutes and Cardiovascular Morbidity and Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients: Results from the Retained Organic Solutes and Clinical Outcomes (ROSCO) Investigators. PloS One. 2015;10(5):e0126048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zoccali C, Bode-Boger S, Mallamaci F, et al. Plasma concentration of asymmetrical dimethylarginine and mortality in patients with end-stage renal disease: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358(9299):2113–2117. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)07217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaysen GA, Johansen KL, Chertow GM, et al. Associations of Trimethylamine N-Oxide With Nutritional and Inflammatory Biomarkers and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients New to Dialysis. J Ren Nutr. 2015;25(4):351–356. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shafi T, Powe NR, Meyer TW, et al. Trimethylamine N-Oxide and Cardiovascular Events in Hemodialysis Patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(1):321–331. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016030374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurella Tamura M, Chertow GM, Depner TA, et al. Metabolic Profiling of Impaired Cognitive Function in Patients Receiving Dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(12):3780–3787. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sirich TL, Funk BA, Plummer NS, Hostetter TH, Meyer TW. Prominent accumulation in hemodialysis patients of solutes normally cleared by tubular secretion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(3):615–622. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013060597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klein J, Bascands JL, Mischak H, Schanstra JP. The role of urinary peptidomics in kidney disease research. Kidney Int. 2016;89(3):539–545. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Magalhaes P, Mischak H, Zurbig P. Urinary proteomics using capillary electrophoresis coupled to mass spectrometry for diagnosis and prognosis in kidney diseases. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2016;25(6):494–501. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van JA, Scholey JW, Konvalinka A. Insights into Diabetic Kidney Disease Using Urinary Proteomics and Bioinformatics. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28(4):1050–1061. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2016091018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uhlen M, Fagerberg L, Hallstrom BM, et al. Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science. 2015;347(6220):1260419. doi: 10.1126/science.1260419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Y, Yang CR, Raghuram V, Parulekar J, Knepper MA. BIG: a large-scale data integration tool for renal physiology. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;311(4):F787–F792. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00249.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ju W, Nair V, Smith S, et al. Tissue transcriptome-driven identification of epidermal growth factor as a chronic kidney disease biomarker. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(316):316ra193. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hodgin JB, Nair V, Zhang H, et al. Identification of cross-species shared transcriptional networks of diabetic nephropathy in human and mouse glomeruli. Diabetes. 2013;62(1):299–308. doi: 10.2337/db11-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez-Gomez MV, Sanchez-Nino MD, Sanz AB, et al. Targeting inflammation in diabetic kidney disease: early clinical trials. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25(9):1045–1058. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2016.1196184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapiro JP, Biswas S, Merchant AS, et al. A quantitative proteomic workflow for characterization of frozen clinical biopsies: laser capture microdissection coupled with label-free mass spectrometry. J Proteomics. 2012;77:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sethi S, Theis JD, Vrana JA, et al. Laser microdissection and proteomic analysis of amyloidosis, cryoglobulinemic GN, fibrillary GN, and immunotactoid glomerulopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(6):915–921. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07030712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Satoskar AA, Shapiro JP, Bott CN, et al. Characterization of glomerular diseases using proteomic analysis of laser capture microdissected glomeruli. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(5):709–721. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Klein J, Lacroix C, Caubet C, et al. Fetal urinary peptides to predict postnatal outcome of renal disease in fetuses with posterior urethral valves (PUV) Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(198):198ra106. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schmidt IM, Hall IE, Kale S, et al. Chitinase-like protein Brp-39/YKL-40 modulates the renal response to ischemic injury and predicts delayed allograft function. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(2):309–319. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012060579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pisitkun T, Shen RF, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(36):13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonzales PA, Pisitkun T, Hoffert JD, et al. Large-scale proteomics and phosphoproteomics of urinary exosomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(2):363–379. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duranton F, Lundin U, Gayrard N, et al. Plasma and urinary amino acid metabolomic profiling in patients with different levels of kidney function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(1):37–45. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06000613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sharma K, Karl B, Mathew AV, et al. Metabolomics reveals signature of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1901–1912. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMahon GM, Hwang SJ, Clish CB, et al. Urinary metabolites along with common and rare genetic variations are associated with incident chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1426–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Anglicheau D, Suthanthiran M. Noninvasive prediction of organ graft rejection and outcome using gene expression patterns. Transplantation. 2008;86(2):192–199. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31817eef7b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Barutta F, Tricarico M, Corbelli A, et al. Urinary exosomal microRNAs in incipient diabetic nephropathy. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e73798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gerstzen RE, Wang TJ. The search for new cardiovascular biomarkers. Nature. 2008;451(7181):949–52. doi: 10.1038/nature06802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]