Abstract

Background

The expression of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is multidimensional. Disease heterogeneity in patients with CRS remains poorly understood. This study aimed to identify endotypes of CRS using cluster analysis by integrating multidimensional characteristics and to explore their association with treatment outcomes.

Methods

A total of 28 clinical variables and 39 mucosal cellular and molecular variables were analyzed using principal component analysis. Cluster analysis was performed on 246 prospectively recruited Chinese CRS patients with at least one-year post-operative follow-up. Difficult-to-treat CRS was characterized in each generated cluster.

Results

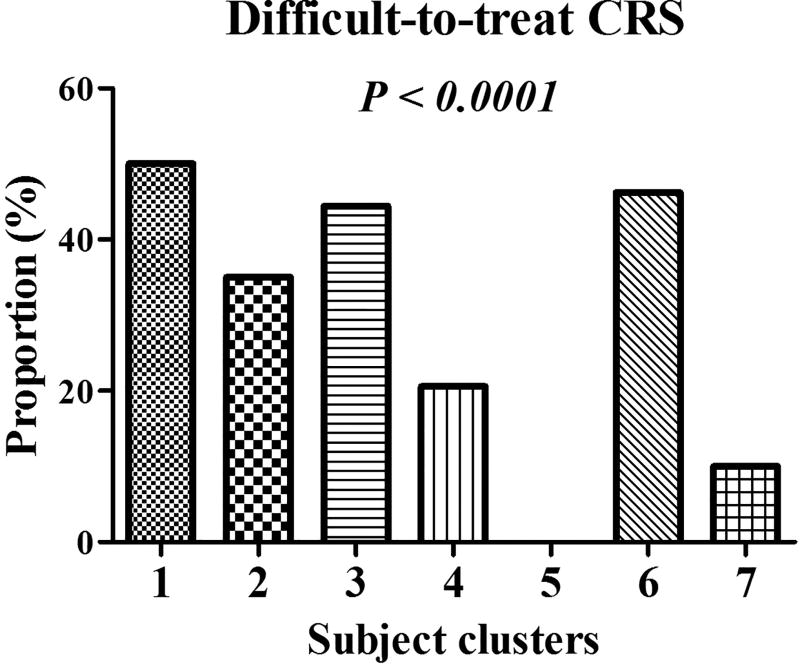

Seven subject clusters were identified. Cluster 1 (13.01%) was comparable to the classic well-defined eosinophilic CRS with polyps, having severe disease and the highest proportion of difficult-to-treat CRS. Patients in cluster 2 (16.26%) and cluster 4 (13.82%) had relatively lower proportions of presence of polyps and presented mild inflammation with moderate proportions of difficult-to-treat cases. Subjects in cluster 2 were highly atopic. Cluster 3 (7.31%) and cluster 6 (21.14%) were characterized by severe or moderate neutrophilic inflammation, respectively, and with elevated levels of IL-8 and high proportions of difficult-to-treat CRS. Cluster 5 (4.07%) was a unique group characterized by the highest levels of IL-10 and lacked difficult-to-treat cases. Cluster 7 (24.39%) demonstrated the lowest symptom severity, a low proportion of difficult-to-treat CRS, and low inflammation load. Finally, we found that difficult-to-treat CRS was associated with distinct clinical features and biomarkers in the different clusters.

Conclusions

Distinct clinicopathobiologic clusters of CRS display differences in clinical response to treatments and characteristics of difficult-to-treat CRS.

Keywords: Cluster analysis, chronic rhinosinusitis, difficult-to-treatment, nasal polyps

INTRODUCTION

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is an inflammatory disorder of the sinonasal mucosae orchestrated by various structural and immune cells, such as epithelial cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils, producing inflammatory mediators including cytokines, chemokines and immunoglobulins (1). Currently, CRS is defined by at least 12 weeks of cardinal sinonasal symptoms, along with visible evidence of inflammation on endoscopic or radiologic examination and is classified into two clinical phenotypes: CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) and CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) (1, 2). This definition obviously allows a heterogeneous group of patients to be included under this term. It has been found that many patients do not respond well to the “one-size fits-all” treatment approach with anti-inflammatory agents and surgery based on current classification (1), supporting the notion that CRS is a multifactorial disorder with diverse and overlapping pathologies and clinical phenotypes (3–10). Therefore, identification of endotypes of CRS determined by distinct pathophysiological mechanisms, and further characterizing the CRS uncontrolled by current treatment regimens may provide a foundation, from which to understand disease causality and ultimately to develop efficient management approaches (1, 11, 12).

Clinical and statistical efforts have assigned CRS endotypes, with recent emphasis on cluster analysis (5–10). In most studies, clustering was performed on white patients by using clinical variables (5, 8–10). For example, Soler et al reported that CRS patients could be separated into 5 clusters with different responses to surgical and medical intervention using 3 clinical variables (5). Although those findings are interesting, the clusters identified do not necessarily relate to or give insights into the underlying pathological mechanisms. Tomassen et al elegantly reported that based on the mucosal expression of 14 molecular markers, CRS patients could be grouped into 10 clusters with diverse inflammatory features (6). However, in their study, a number of inflammatory markers implicated in the pathogenesis of CRS were not included for the definition of an endotype and the impact of endotype on treatment response was not studied (6).

Since heterogeneity in CRS expression is multidimensional, including variability in clinical, physiologic, and pathologic parameters, classification requires consideration of these disparate domains in a unified model. Thus, our present study aimed to endotype Chinese patients with CRS by integrating multidimensional characteristics in one cluster analysis and to dissect the association between endotype and clinical response to treatment. Previous studies demonstrated considerable differences in clinical and pathological features of CRS in patients with distinct racial backgrounds (3, 13–15). It is therefore believed that further understanding of CRS in populations with distinct racial backgrounds will be of great value in the elucidation of the pathogenesis of CRS.

METHODS

Subjects

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tongji Hospital of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, and was conducted with written informed consent from all patients. CRSwNP and CRSsNP were diagnosed according to the current American and European position papers (1, 2). All patients had ongoing symptoms after initial attempts at medical treatment and underwent functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Patients who had a history of aspirin sensitivity, antrochoanal polyps, cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, fungal sinusitis, or systemic vasculitis were excluded in this study, because these are discrete disorders with unique pathophysiology. Additional information is provided in this article’s Online Supplement.

Baseline and follow-up clinical assessments

The demographic and clinical characteristics listed in Table 1 were assessed before surgery as previously described (1, 15–19). A complete peripheral blood cell count with differential was performed by automated analysis (20). Diseased ethmoid sinus mucosa and polyp samples were harvested from CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients during surgery, respectively. Control patients undergoing septoplasty because of anatomic variations and without other sinonasal diseases were recruited. One biopsy was taken from the inferior turbinate mucosa during surgery (3).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of CRS clusters

| Cluster 1 (n = 32) |

Cluster 2 (n = 40) |

Cluster 3 (n = 18) |

Cluster 4 (n = 34) |

Cluster 5 (n = 10) |

Cluster 6 (n = 52) |

Cluster 7 (n = 60) |

Overall P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male (%) | 16 (50.00) | 24 (60.00) | 10 (55.56) | 30 (88.24) | 8 (80.00) | 38 (73.08) | 30 (50.00) | 0.003 |

| Age (y) | 44.50 (37.25–49.75) | 25.50 (17.00–44.50) | 46.00 (29.25–54.25) | 22.00 (18.00–35.25) | 41.50 (31.25–50.75) | 42.50 (37.00–55.75) | 43.50 (36.50–52.00) | <0.001 |

| Eosinophilic CRS, n (%) | 30 (93.75) | 12 (30.00) | 4 (22.22) | 6 (17.65) | 2 (20.00) | 22 (42.31) | 18 (30.00) | <0.001 |

| Patients with atopy, n (%) | 12 (37.50) | 24 (60.00) | 6 (33.33) | 5 (14.71) | 5 (50.00) | 14 (26.92) | 12 (20.00) | <0.001 |

| Patients with smoking exposure, n (%) | 10 (33.33) | 6 (15.00) | 4 (22.22) | 8 (23.53) | 6 (60.00) | 10 (19.23) | 8 (13.33) | 0.026 |

| Patients with AR, n (%) | 12 (37.50) | 8 (20.00) | 0 (0) | 2 (5.88) | 0 (0) | 4 (7.69) | 4 (6.67) | <0.001 |

| Patients with asthma, n (%) | 16 (50.00) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.33) | <0.001 |

| Patients with prior surgery, n (%) | 14 (43.75) | 2 (5.00) | 8 (44.44) | 10 (29.41) | 2 (20.00) | 28 (53.85) | 16 (26.67) | <0.001 |

| Patients with nasal polyps, n (%) | 32 (100) | 14 (35.00) | 14 (77.78) | 18 (52.94) | 8 (80.00) | 52 (100) | 46 (76.67) | <0.001 |

| Disease duration (y) | 5.00 (1.25–9.25) | 2.00 (1.00–5.00) | 1.00 (0.15–9.25) | 3.00 (0.46–7.25) | 3.00 (1.50–7.75) | 8.50 (3.00–10.00) | 2.00 (0.50–10.00) | 0.011 |

| Nasal obstruction VAS score | 7.50 (3.75–10.00) | 7.00 (5.00–8.00) | 6.00 (5.50–8.00) | 6.00 (5.00–8.00) | 7.00 (5.50–8.25) | 8.00 (5.00–9.00) | 5.00 (1.00–6.00) | <0.001 |

| Headache VAS score | 2.50 (0.25–6.00) | 5.00 (3.00–6.75) | 3.00 (0.00–5.00) | 2.00 (0.75–4.25) | 3.00 (1.75–4.50) | 2.50 (0.00–5.00) | 1.00 (0.00–3.00) | <0.001 |

| Facial pain VAS score | 0.50 (0.00–3.00) | 3.00 (0.00–6.00) | 0.00 (0.00–5.00) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.00 (0.00–2.50) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | 0.00 (0.00–1.00) | <0.001 |

| Loss of smell VAS score | 9.50 (7.25–10.00) | 2.00 (0.00–6.00) | 2.00 (0.00–5.25) | 2.00 (0.00–5.25) | 2.00 (0.75–8.50) | 9.00 (7.00–10.00) | 2.00 (0.00–5.00) | <0.001 |

| Rhinorrhea VAS score | 6.00 (5.00–8.00) | 7.00 (5.00–8.00) | 6.00 (3.00–8.50) | 7.00 (4.75–8.00) | 5.00 (4.75–7.50) | 5.50 (2.00–8.00) | 3.00 (0.00–5.00) | <0.001 |

| Total symptom VAS score | 28.50 (20.50–31.00) | 24.00 (16.25–29.25) | 19.00 (12.00–28.25) | 17.00 (13.00–25.25) | 18.00 (15.25–28.50) | 23.50 (18.00–30.00) | 11.50 (10.00–15.00) | <0.001 |

| Overall burden VAS score | 7.00 (5.00–8.00) | 6.50 (5.00–8.00) | 5.00 (4.75–6.50) | 7.00 (5.00–8.00) | 7.00 (4.50–7.50) | 6.50 (5.00–8.00) | 5.00 (3.00–6.00) | <0.001 |

| Nasal polyp score | 3.50 (2.00–4.00) | 0.00 (0.00–2.00) | 2.00 (0.75–4.00) | 1.00 (0.00–2.25) | 2.00 (1.50–3.25) | 4.00 (4.00–5.00) | 2.00 (1.00–3.00) | <0.001 |

| Bilateral CT score | 22.50 (16.25–24.00) | 8.00 (4.25–14.00) | 14.00 (8.50–20.50) | 12.00 (6.75–14.25) | 18.00 (11.00–24.00) | 20.50 (17.00–23.00) | 10.50 (6.00–14.00) | <0.001 |

| Total endoscopic score | 10.00 (8.00–11.75) | 5.50 (3.25–6.00) | 9.00 (6.75–11.00) | 7.00 (4.00–8.25) | 9.00 (6.50–9.75) | 10.00 (8.00–12.00) | 6.00 (4.00–8.00) | <0.001 |

| Blood leukocyte count (×109/L) | 7.14 (5.57–7.95) | 5.37 (4.52–6.32) | 5.68 (4.72–6.58) | 8.48 (7.41–9.37) | 6.16 (5.17–7.57) | 5.70 (5.07–6.42) | 5.76 (4.73–6.44) | <0.001 |

| Blood neutrophil count (×109/L) | 3.29 (2.70–4.24) | 2.70 (2.18–3.18) | 2.83 (2.44–3.62) | 5.13 (4.40–6.64) | 3.69 (2.70–4.38) | 3.18 (2.76–3.57) | 2.81 (2.46–3.63) | <0.001 |

| Blood neutrophil percent (%) | 47.15 (41.55–55.60) | 47.65 (42.28–51.43) | 48.00 (45.78–56.40) | 62.30 (56.23–67.60) | 60.50 (52.30–61.33) | 53.65 (48.13–58.55) | 54.45 (44.80–57.08) | <0.001 |

| Blood lymphocyte count (×109/L) | 2.46 (1.85–2.75) | 2.14 (1.99–2.46) | 2.19 (1.70–3.30) | 2.01 (1.69–2.51) | 2.18 (1.61–2.25) | 1.89 (1.61–2.26) | 1.92 (1.63––2.33) | <0.001 |

| Blood lymphocyte percent (%) | 35.55 (29.45–38.98) | 42.15 (36.28–46.83) | 42.80 (35.40–43.50) | 25.25 (21.45–30.40) | 35.00 (28.53–42.73) | 33.70 (29.68–38.70) | 33.55 (29.58–41.18) | <0.001 |

| Blood eosinophil count (×109/L) | 0.75 (0.41–1.11) | 0.14 (0.09–0.21) | 0.17 (0.10–0.23) | 0.18 (0.13–0.22) | 0.18 (0.05–0.30) | 0.15 (0.09–0.32) | 0.22 (0.11–0.36) | <0.001 |

| Blood eosinophil percent (%) | 9.95 (6.38–16.28) | 2.30 (1.25–3.68) | 2.75 (1.85–4.03) | 2.70 (1.40–3.18) | 2.30 (1.28–4.80) | 3.25 (1.85–5.20) | 3.65 (1.63–5.98) | <0.001 |

| Blood monocyte count (×109/L) | 0.52 (0.43–0.63) | 0.38 (0.34–0.46) | 0.46 (0.38–0.71) | 0.74 (0.58–1.12) | 0.43 (0.40–0.45) | 0.42 (0.32–0.53) | 0.46 (0.36–0.57) | <0.001 |

| Blood monocyte percent (%) | 7.90 (6.85–8.83) | 6.75 (6.00–8.20) | 8.10 (7.85–10.25) | 7.85 (6.28–16.85) | 6.60 (5.75–8.45) | 7.65 (6.63–9.20) | 8.05 (6.20–9.08) | 0.028 |

For continuous variables, results are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables are summarized using frequency and percentage. An overall test of the distribution of each characteristic across clusters was performed using a Kruskal-Wallis H test for continuous variables and a chi-squared test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Overall P values indicate differences among the 7 clusters. Overall P values less than 0.05 indicate that at least one out of the 7 clusters was different from other clusters.

The numbers in red color indicate the highest value of a particular variable among 7 clusters, whereas the numbers in blue color indicate the lowest value of a particular variable among 7 clusters.

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; AR, allergic rhinitis; VAS, visual analog scale; CT, computed tomography.

After surgery, patients were under a “standardized” treatment and follow-up according to the current American and European position papers (1, 2, 21). The outcome was determined at follow-up one year postoperatively. According to the definition proposed by the European position paper (1), patients who did not reach an acceptable level of control despite adequate surgery, intranasal corticosteroid treatment, and up to 2 short courses of antibiotics or systemic corticosteroids in the last year were considered to have difficult-to-treat CRS (1). Additional information is provided in this article’s Online Supplement.

Measurement of cellular markers in tissues

Paraffin sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or a polyclonal antibody to myeloperoxidase (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The numbers of eosinophils, mononuclear cells, plasma cells, submucosal glands, and myeloperoxidase positive neutrophils per high power field (HPF) were counted (3). CRS was defined as eosinophilic when the percent of tissue eosinophils exceeded 10% of total infiltrating cells, as reported in our previous study (3). Additional information is provided in this article’s Online Supplement.

Measurement of molecular markers in tissues

As previously reported (15), tissue samples were weighed and homogenized. The protein levels of 35 molecules in supernatants were detected using the Bio-Plex suspension chip method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif, USA) (22). The protein concentrations of detected molecular markers were normalized to total tissue protein levels (22). Cytokine values below the level of assay detection were replaced by the values representing 1/10 of the detection limit (23). Additional information is provided in this article’s Online Supplement with table S1.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the R version 3.2.4 software and IBM SPSS 22.0 package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) (24). For continuous variables, results are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), or in box and whisker plots. Data distribution was tested for normality using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or a Shapiro-Wilk test. Since variables were not normally distributed, a Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to assess significant intergroup variability among more than 2 groups and a Mann-Whitney U 2-tailed test was used for between-group comparison. For dichotomous variables, a chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine the difference between groups, whichever is appropriate. Significance was accepted at P < .05, which was adjusted using a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (25).

For cluster analysis, continuous variables were standardized using z scores and categorical variables were expressed as 0 or 1 (26). Principal component analysis was performed to analyze relationships between variables to choose the variables most relevant to the study (6). Orthogonal rotation with Kaiser normalization was performed, and only variables with loadings of greater than 0.4 were retained (6). Next, the subjects were sorted into groups by using k-means method based on the correlation ratio and mixed principal component analysis (5, 6, 26). The optimal number of clusters was determined by NbClust in R software package, which uses a wide variety of indices to find the optimal number of clusters in a partitioning of a data set during the clustering process (27). The priori power analysis suggests that a sample size of 246 CRS patients will provide enough power (p ≥ 0.8) to detect a medium differences among the clusters (e.g. Cohen’s f ranging from 0.18 to 0.25 corresponding to a number of clusters ranging from 2 to 8 if the sample is homogeneously distributed within clusters). The non-parametric tests will provide more power when the data are not normally distributed (28, 29).

RESULTS

Study cohort

Three hundred and twenty one CRS participants were recruited; however, 75 (23.36%) were excluded because of incomplete/missing data (3 patients), inadequate amount of tissue for analysis (22 patients), or loss to follow-up (50 patients) (Fig. S1), leaving 246 CRS patients for analyses. In addition, 16 control subjects were analyzed as a reference for comparing the difference between CRS and control subjects. No significant differences in demographic and clinical characteristics were found between patients who completed the study and patients excluded because of inadequate sample amount and lost to follow-up (Table S2).

Difference between CRSwNP and CRSsNP patients

There were 184 (74.8%) CRSwNP and 62 (25.2%) CRSsNP patients. Consistent with previous reports (1–4), CRSwNP and CRSsNP demonstrated considerable difference in a number of clinical and inflammatory characteristics (Tables S3 and S4); however, no significant difference in the proportion of difficult-to-treat cases was discovered between the CRSwNP (33.7%) and CRSsNP (20.97%) groups (Fig. S2). Additional data are provided in this article’s Online Supplement including tables S5 and S6.

Clustering results

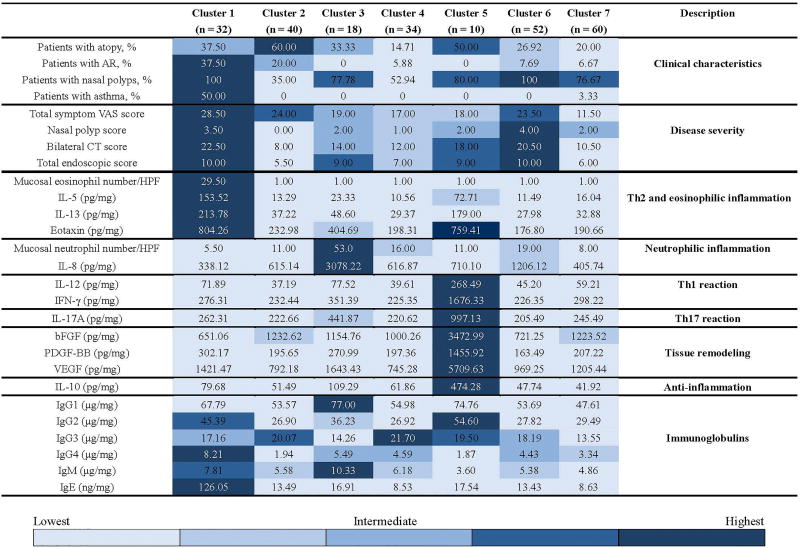

We first performed principal component analysis to reduce dimensionality of variables from a total of 67. Seven components (54 variables) were retained explaining 75% of all variance in the data (Table S7). Analysis of remaining 54 multidimensional variables produced an optimal outcome of 7 subject clusters (Table S8). A modified heat map, overlaid with a graded color scheme representing quintiles of data, was created to indicate the relative degree to which some key variables were present across clusters (Fig. 1) (30).

Fig 1.

A modified heat map indicating the relative degree to which some key variables were present across clusters. The graded color scheme contains 5 shades of blue, representing the 20th (lightest), 40th, 60th, 80th, and 100th (darkest) percentiles of the data for each row. For continuous variables, results are expressed as medians. Categorical variables are summarized using percentage. The protein concentrations of detected molecular markers were normalized to total tissue protein levels. AR, allergic rhinitis; VAS, visual analog scale; CT, computed tomography; HPF, high-power field.

Cluster 1: Type 2 response dominated eosinophilic CRSwNP with severe clinical manifestations and poor treatment outcomes (n = 32 [13.01%])

All the subjects in cluster 1 were CRSwNP patients (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). This cluster had the highest frequency of co-existence of allergic rhinitis and asthma (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). This cluster also had the highest hyposmia scores, total symptom scores, overall symptom burden scores, and computed tomography (CT) scores (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). This cluster was also one of the top 2 clusters with high endoscopic scores (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). This cluster presented the highest blood eosinophil count and percent, mucosal eosinophil count, and mucosal levels of IL-5, IL-13, eotaxin, IgG4 and IgE, whereas it had the lowest tissue levels of IL-8 and mucosal neutrophil infiltration (Tables 1 and 2, Fig. 1, and Figs. S4 and S5). This cluster also had the lowest mucosal levels of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and granulocytes colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Cluster 1 also demonstrated significant differences in these cellular and molecular markers compared with controls (Table 2 and Table S4). Importantly, this cluster had the highest proportion (50%) of difficult-to-treat cases (Fig. 2). In this cluster, compared with non-difficult-to treat CRS and controls, difficult-to-treat CRS subjects were predominantly women, and had a particularly high frequency of asthma comorbidity, and demonstrated higher bilateral CT scores and increased levels of IL-5, IgG4, and IgE (Table S9).

Table 2.

Cellular and molecular profiles in sinonasal mucosa of CRS clusters

| Cluster 1 (n = 32) |

Cluster 2 (n = 40) |

Cluster 3 (n = 18) |

Cluster 4 (n = 34) |

Cluster 5 (n = 10) |

Cluster 6 (n = 52) |

Cluster 7 (n = 60) |

Overall P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mucosal eosinophil number/HPF | 29.50 (21.50–81.75) | 1.00 (0.00–5.75) | 1.00 (1.00–8.50) | 1.00 (0.00–1.75) | 1.00 (0.75–19.50) | 1.00 (1.00–16.00) | 1.00 (0.00–11.00) | <0.001 |

| Mucosal neutrophil number/HPF | 5.50 (3.00–12.00) | 11.00 (5.50–22.50) | 53.0 (31.0–65.75) | 16.00 (8.25–25.25) | 11.00 (9.00–19.75) | 19.00 (11.00–23.00) | 8.00 (4.00–13.00) | <0.001 |

| Mucosal plasma cell number/ HPF | 4.00 (2.25–5.75) | 4.0 (1.25–6.00) | 6.00 (2.75–7.00) | 4.00 (3.75–8.00) | 1.00 (0.00–4.75) | 6.00 (4.00–8.00) | 4.00 (2.00–6.00) | 0.003 |

| Mucosal mononuclear cell number/HPF | 24.50 (21.25–30.25) | 24.50 (16.50–26.75) | 26.00 (21.00–30.75) | 32.00 (21.75–36.000) | 25.00 (24.75–30.00) | 34.50 (20.00–47.00) | 28.50 (21.00–38.00) | 0.069 |

| Mucosal gland number/HPF | 1.00 (0.25–3.50) | 3.00 (2.00–4.00) | 2.00 (0.75–4.00) | 2.00 (1.00–5.00) | 3.00 (2.25–4.75) | 1.50 (1.00–5.00) | 2.00 (1.00–4.00) | 0.207 |

| IL-1β (pg/mg) | 10.32 (4.20–15.66) | 16.79 (6.70–34.76) | 74.63 (25.81–94.50) | 11.68 (8.30–17.98) | 25.79 (17.34–42.39) | 12.17 (5.65–18.06) | 13.00 (7.96–18.81) | <0.001 |

| IL-1Ra (ng/mg) | 1.40 (0.68–2.06) | 1.94 (1.33–3.00) | 5.41 (2.97–8.57) | 2.00 (1.32–3.26) | 4.24 (2.48–5.54) | 1.45 (0.87–1.94) | 1.60 (0.93–2.64) | <0.001 |

| IL-2 (pg/mg) | 1.31 (0.94–3.00) | 1.57 (1.02–2.06) | 3.12 (1.37–3.93) | 1.42 (1.10–2.01) | 7.47 (3.80–11.36) | 1.32 (0.79–1.75) | 1.61 (1.10–2.31) | <0.001 |

| IL-4 (pg/mg) | 126.36 (70.04–218.48) | 109.18 (80.00–143.95) | 127.03 (90.08–244.49) | 88.97 (76.90–136.08) | 458.50 (276.07–510.31) | 108.24 (67.01–118.07) | 109.52 (80.52–152.77) | <0.001 |

| IL-5 (pg/mg) | 153.52 (93.05–287.65) | 13.29 (9.00–21.95) | 23.33 (8.12–30.88) | 10.56 (6.93–17.51) | 72.71 (51.13–109.82) | 11.49 (8.35–15.63) | 16.04 (10.42–34.05) | <0.001 |

| IL-6 (pg/mg) | 118.74 (58.73–197.28) | 108.06 (56.48–259.51) | 230.43 (165.54–270.82) | 93.48 (50.90–126.94) | 160.16 (141.89–387.06) | 91.08 (49.57–173.78) | 58.54 (38.35–129.22) | <0.001 |

| IL-7 (pg/mg) | 371.86 (234.87–588.11) | 269.17 (220.94–428.24) | 428.14 (211.20–548.49) | 307.66 (179.83–383.08) | 1110.48 (1043.80–2084.56) | 227.94 (175.37–299.88) | 355.12 (231.76–493.14) | <0.001 |

| IL-8 (pg/mg) | 338.12 (263.82–672.55) | 615.14 (293.13–1099.54) | 3078.22 (2042.11–3472.04) | 616.87 (510.17–1090.53) | 710.10 (617.04–1059.96) | 1206.12 (563.42–1568.56) | 405.74 (355.12–708.18) | <0.001 |

| IL-9 (pg/mg) | 113.55 (61.31–137.14) | 85.15 (61.68–127.92) | 85.08 (70.11–172.77) | 78.09 (56.44–93.30) | 322.95 (274.98–660.61) | 68.93 (38.29–80.37) | 79.98 (43.59–125.45) | <0.001 |

| IL-10 (pg/mg) | 79.68 (4.00–136.91) | 51.49 (2.19–100.33) | 109.29 (53.34–178.70) | 61.86 (8.49–117.47) | 474.28 (403.10–806.47) | 47.74 (22.77–104.66) | 41.92 (2.23–155.64) | <0.001 |

| IL-12 (pg/mg) | 71.89 (37.72–99.27) | 37.19 (21.55–71.77) | 77.52 (43.34–116.97) | 39.61 (28.93–64.24) | 268.49 (218.93–466.31) | 45.20 (29.41–66.61) | 59.21 (24.15–83.47) | <0.001 |

| IL-13 (pg/mg) | 213.78 (112.01–300.31) | 37.22 (22.90–55.55) | 48.60 (24.48–80.56) | 29.37 (20.40–37.51) | 179.00 (93.88–213.77) | 27.98 (20.87–44.49) | 32.88 (24.49–69.81) | <0.001 |

| IL-15 (pg/mg) | 14.45 (8.69–19.34) | 10.67 (7.23–17.91) | 21.65 (8.90–26.02) | 11.36 (7.57–15.19) | 30.58 (27.39–51.36) | 10.78 (8.32–13.56) | 12.19 (9.96–15.73) | <0.001 |

| IL-17A (pg/mg) | 262.31 (182.82–443.33) | 222.66 (176.39–343.17) | 441.87 (173.72–539.75) | 220.62 (159.99–305.52) | 997.13 (660.47–997.13) | 205.49 (152.58–247.96) | 245.49 (185.86–360.28) | <0.001 |

| IL-22 (pg/mg) | 9.27 (5.76–19.17) | 8.42 (5.06–16.38) | 11.99 (7.09–17.83) | 6.78 (5.99–11.99) | 68.15 (46.36–148.67) | 5.58 (4.42–8.68) | 11.08 (5.61–18.17) | <0.001 |

| IL-25 (pg/mg) | 1.59 (1.07–4.22) | 2.13 (1.67–4.24) | 1.83 (1.35–4.28) | 2.18 (1.31–2.59) | 8.68 (7.76–37.97) | 2.06 (1.37–3.04) | 2.78 (1.59–4.65) | <0.001 |

| IL-33 (ng/mg) | 4.51 (1.83–6.39) | 5.77 (2.54–8.26) | 3.73 (2.96–12.60) | 5.69 (2.49–6.66) | 12.38 (9.47–16.87) | 6.20 (3.10–7.80) | 6.07 (3.87–11.11) | 0.001 |

| Eotaxin (pg/mg) | 804.26 (384.23–1104.05) | 232.98 (149.62–323.06) | 404.69 (152.08–603.28) | 198.31 (134.26–277.10) | 759.41 (587.13–1107.45) | 176.80 (149.40–274.33) | 190.66 (154.03–352.00) | <0.001 |

| bFGF (pg/mg) | 651.06 (239.39–802.36) | 1232.62 (814.82–2139.27) | 1154.76 (978.91–1423.73) | 1000.26 (832.24–1537.29) | 3472.99 (1905.56–4139.85) | 721.25 (564.36–1046.60) | 1223.52 (784.62–2205.34) | <0.001 |

| G-CSF (pg/mg) | 134.70 (71.34–265.52) | 507.72 (173.62–1045.57) | 4126.53 (651.30–6347.20) | 728.26 (446.61–2362.98) | 329.00 (254.35–663.66) | 1253.50 (455.07–2898.46) | 241.50 (86.60–513.05) | <0.001 |

| IFN-γ (pg/mg) | 276.31 (186.97–434.78) | 232.44 (187.37–345.12) | 351.39 (210.61–589.92) | 225.35 (160.28–328.27) | 1676.33 (959.16–1852.40) | 226.35 (153.03–309.16) | 298.22 (164.32–345.06) | <0.001 |

| IP-10 (ng/mg) | 2.06 (0.76–3.37) | 3.48 (2.49–8.66) | 3.99 (2.18–7.35) | 2.75 (1.72–1.62) | 6.35 (5.32–15.57) | 1.80 (1.12–3.21) | 2.71 (1.83–5.08) | <0.001 |

| MCP-1 (pg/mg) | 920.78 (574.88–1205.09) | 580.18 (333.76–867.00) | 1154.76 (978.91–1423.73) | 478.24 (303.60–611.39) | 887.75 (721.15–1566.23) | 592.14 (420.55–792.85) | 494.93 (396.05–712.90) | <0.001 |

| MIP-1α (pg/mg) | 26.63 (11.94–52.33) | 26.95 (15.49–39.19) | 46.71 (19.53–68.14) | 22.32 (14.64–28.30) | 108.15 (66.24–130.95) | 20.77 (8.58–25.60) | 18.12 (11.72–25.80) | <0.001 |

| PDGF-BB (pg/mg) | 302.17 (147.89–422.56) | 195.65 (137.08–327.66) | 270.99 (159.47–443.14) | 197.36 (121.51–314.48) | 1455.92 (1068.21–1786.82) | 163.49 (143.09–214.64) | 207.22 (149.36–383.49) | <0.001 |

| MIP-1β (pg/mg) | 691.79 (386.16–1035.72) | 501.61 (263.90–754.80) | 972.10 (372.72–1366.84) | 393.70 (308.47–535.26) | 611.53 (450.65–1424.11) | 337.52 (209.57–449.46) | 433.25 (263.85–622.36) | <0.001 |

| TNF-α (pg/mg) | 146.74 (101.19–241.00) | 144.06 (102.17–217.00) | 229.81 (102.58–407.39) | 119.44 (87.97–175.56) | 875.44 (514.65–1299.06) | 130.02 (87.95–159.52) | 137.04 (92.83–176.87) | <0.001 |

| VEGF (pg/mg) | 1421.47 (689.90–2668.54) | 792.18 (493.93–1593.24) | 1643.43 (945.05–2133.55) | 745.28 (419.68–1410.19) | 5709.63 (3831.49–8241.59) | 969.25 (647.21–1595.08) | 1205.44 (635.85–2087.55) | <0.001 |

| IgG1 (µg/mg) | 67.79 (48.61–85.79) | 53.57 (38.27–64.48) | 77.00 (62.06–202.70) | 54.98 (45.14–67.78) | 74.76 (66.76–86.54) | 53.69 (36.06–81.46) | 47.61 (36.67–62.55) | <0.001 |

| IgG2 (µg/mg) | 45.39 (27.80–65.34) | 26.90 (15.60–58.43) | 36.23 (31.16–49.60) | 26.92 (18.00–38.82) | 54.60 (30.34–82.90) | 27.82 (19.35–44.27) | 29.49 (18.84–38.58) | 0.001 |

| IgG3 (µg/mg) | 17.16 (6.23–26.14) | 20.07 (13.89–55.74) | 14.26 (12.40–33.44) | 21.70 (10.58–31.95) | 19.50 (12.62–21.51) | 18.19 (7.74–32.97) | 13.55 (9.63–21.66) | 0.030 |

| IgG4 (µg/mg) | 8.21 (5.56–13.15) | 1.94 (0.66–6.32) | 5.49 (3.77–13.31) | 4.59 (3.10–5.42) | 1.87 (1.26–2.15) | 4.43 (2.01–7.06) | 3.34 (1.86–6.90) | <0.001 |

| IgM (µg/mg) | 7.81 (4.87–10.17) | 5.58 (3.28–7.28) | 10.33 (5.52–17.61) | 6.18 (4.60–7.83) | 3.60 (2.66–7.65) | 5.38 (3.30–8.25) | 4.86 (2.60–6.65) | <0.001 |

| IgE (ng/mg) | 126.05 (59.41–315.22) | 13.49 (5.83–30.50) | 16.91 (12.53–56.68) | 8.53 (6.90–15.86) | 17.54 (51.4–41.10) | 13.43 (4.91–33.22) | 8.63 (4.55–44.60) | <0.001 |

The protein concentrations of detected molecular markers were normalized to total tissue protein levels.

For continuous variables, results are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges. An overall test of the distribution of each characteristic across clusters was performed using a Kruskal-Wallis H test. Overall P values indicate differences among the 7 clusters. Overall P values less than 0.05 indicate that at least one out of the 7 clusters was different from other clusters.

The numbers in red color indicate the highest value of a particular variable among 7 clusters, whereas the numbers in blue color indicate the lowest value of a particular variable among 7 clusters.

CRS, chronic rhinosinusitis; HPF, high-power field; IL, interleukin; IL-1Ra, IL-1 receptor antagonist; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; G-CSF, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IP-10, IFN-γ-induced protein 10; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; MIP, macrophage inflammatory protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor α; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; PDGF-BB, platelet-derived growth factor-BB; Ig, immunoglobulin.

Fig 2.

The proportions of difficult-to-treat chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) differed by subject clusters. Fisher exact test was used to test the differences in proportions across 7 clusters. An overall P value indicates differences among the 7 clusters. An overall P value less than 0.05 indicates that at least one out of the 7 clusters was different from other clusters.

Cluster 2: Highly atopic CRS with mild inflammation (n = 40 [16.26%])

It was the only cluster in which the majority of subjects were CRSsNP patients (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). Despite the high frequency of atopy in this cluster, these subjects did not manifest significant eosinophilic inflammation. Compared with controls and other clusters, they had mild inflammation and a moderate proportion of difficult-to-treat CRS (35%) (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, the subjects with difficult-to-treat CRS in this cluster had higher CT scores, but lower symptom scores (Table S10). Patients with difficult-to-treat CRS in cluster 2 had a profile of mild eosinophilic inflammation as reflected by slightly increased levels of IL-5 and IL-4 and eosinophil infiltration in comparison with patients with non-difficult-to-treated CRS and controls (Table S10). Simultaneously, some other inflammatory mediators were also mildly elevated in difficult-to-treat CRS (Table S10).

Cluster 3: CRS with neutrophilic inflammation (n = 18 [7.31%])

In this cluster, subjects were older and the majority of them were CRSwNP patients. This cluster had the highest number of mucosal neutrophils accompanied by the highest levels of IL-1β, IL-1Ra, IL-6, IL-8 (CXCL8), G-CSF, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1β (CCL4), IgG1 and IgM, which all differed from controls except IL-1Ra (Table 2, Fig. 1 and Figs. S4 and S5). This cluster also had a high proportion (44.44%) of difficult-to-treat cases (Fig. 2). All the cases with difficult-to-treat CRS in this cluster were CRSwNP and demonstrated higher rhinorrhea scores and bilateral CT scores (Table S11). Moreover, compared with non-difficult-to-treat CRS, difficult CRS in this cluster had higher tissue levels of IL-8 (CXCL8), IL-10, interferon (IFN)-γ, IFN-induced protein 10 (IP-10) (CXCL10) and MIP-1β (CCL4), and increased number of mucosal neutrophils (Table S11). In contrast, non-difficult-to-treat CRS had higher mucosal plasma cell count and IgG4 level (Table S11).

Cluster 4: Young, predominantly male subjects with mild inflammation (n= 34 [13.82%])

Cluster 4 was comprised of primarily male patients with the youngest age (Table 1 and Fig. S3). About half of the patients in this cluster had nasal polyps. These subjects had the highest blood leukocyte and monocyte count, and blood neutrophil count and percent (Table 1 and Fig. S4). Similar to cluster 2, this cluster had mild inflammation (Table 2, Fig. 1 and Fig. S5). This cluster had the highest levels of mucosal IgG3 (Table 2 and Fig. 1). Although this cluster had a low ratio of difficult-to-treat CRS (20.59%) (Fig. 2), the difficult cases in this cluster had a higher rate of prior sinus surgery, and higher CT and total endoscopic scores (Table S12). Similar to cluster 2, difficult-to-treat CRS in this cluster had a profile of moderate eosinophilic inflammation as reflected by increased number of mucosal eosinophils in comparison with patients with non-difficult-to-treat CRS and controls (Tables S3 and S12). Nevertheless, the number of glands was decreased in difficult cases compared with non-difficult-to-treat CRS and controls (Tables S3 and S12).

Cluster 5: CRS with high levels of IL-10 and good treatment outcomes (n = 10 [4.06%])

This was the smallest cluster and lacked difficult-to-treat cases (Fig. 2). The majority of cluster 5 subjects had nasal polyps (80%) (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). Although this group had the high protein levels of a number of inflammatory mediators, this cluster also had remarkably high levels of IL-10 (Table 2, Fig. 1 and Fig. S5). In other clusters, the IL-10 levels were down-regulated compared with controls (Table 2 and Table S4).

Cluster 6: CRSwNP with long disease duration, high rate of prior surgery, and moderate neutrophilic inflammation (n = 52 [21.14%])

Similar to cluster 1, the subjects in this cluster were all CRSwNP patients (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). Patients in this cluster had the longest duration of disease and more frequently had a history of prior sinus surgery. This cluster also had severe polyps as reflected by the highest polyp and endoscopic scores. This cluster had moderate levels of IL-8 and neutrophilic inflammation (Table 2, Fig. 1 and Figs. S4 and S5). This cluster had a high rate of difficult-to-treat CRS (46.15%) (Fig. 2). Compared with non-difficult-to-treat CRS, difficult-to-treat CRS in cluster 6 was more likely to have prior sinus surgery, and higher total symptom and CT scores, and much lower levels of IL-10 (Table S13).

Cluster 7: Mild CRS with low inflammatory load and favorable treatment outcomes (n = 60 [24.39%])

The majority of subjects in this cluster had nasal polyps, and this group had a mild disease severity as reflected by the lowest symptom scores (Table 1, Fig. 1 and Fig. S3). The expression levels of various cellular and molecular biomarkers were lower compared to other clusters (Table 2, Fig. 1 and Fig. S5). In this cluster, subjects were unlikely to have difficult-to-treat CRS (10%) (Fig. 2). Patients with difficult-to-treat CRS all had a history of prior sinus surgery (Table S14). Compared with non-difficult-to-treat CRS and controls, difficult-to-treat CRS in cluster 7 had higher levels of IgG1–4 (Table S14).

DISCUSSION

Although CRSsNP and CRSwNP show certain differences in clinical manifestations and immunopathologic characteristics as revealed by previous studies and our current study (1–4, 31), the presently recommended classification does not adequately reflect the heterogeneous characteristics of CRS that influence both clinical and scientific research in CRS (4, 32–36).

Cluster analysis has been used to characterize subgroups of CRS recently (5–10). However, most efforts have relied primarily on clinical features or a limited number of inflammatory biomarkers (5–10). Interestingly, in our current study, we found that despite the fact that clusters generated using only clinical variables differed significantly in clinical characteristics, they did not have significant difference in expression of various inflammatory factors (Table S15). In contrast, clusters generated only using molecular and cellular factors had significant differences in inflammation profiles, but not in a number of clinical characteristics (Table S16). A major strength of this study is to integrate 39 cellular and molecular variables and 28 clinical variables in one cluster analysis for the first time. It would be more powerful to identify the association between underlying biology and clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes. Here we identified 7 groups, confirming endotypes of previous reports and revealing additional unrecognized endotypes (5, 6), and for the first time characterized the heterogeneity of difficult-to-treat CRS.

Cluster 1 was comparable to the classic well-defined eosinophilic CRSwNP. Although this endotype is commonly found in white CRS patients, as reported by Tomassen et al in their cluster analysis study (6), it appears to only comprise a small portion (13.01%) of the Chinese CRS patients that we have evaluated in this study. The identification of this classic group of patients supports the reliability of our analytic approach. Another strength of the current study is that we prospectively studied treatment responses of patients under "standardized" treatment conditions. We found that cluster 1 had the poorest treatment outcomes, which confirms the previously reported link between eosinophilia and prognosis of CRS (7, 11). Distinct from white patients (3, 6, 14), neutrophil-dominated endotypes were more frequently found in Chinese patients. We found that comparable to cluster 1, neutrophilic inflammation dominated clusters 3 and 6 had high proportions of difficult-to-treat CRS, suggesting that both eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation can lead to severe polyp disease (7). Our previous report indicates that increased neutrophilia may reduce the response to corticosteroid therapy in CRSwNP (36). Corticosteroids were the principal post-surgery treatment in our study; therefore, the high frequency of difficult cases found in clusters with prominent neutrophilic inflammation encourages a search for novel treatments targeting neutrophilic inflammation. Compared with the previous study (6), we included more biomarkers of inflammation, tissue remodeling and adaptive immunity in cluster analysis. Such expansion of biomarkers facilitates the discovery of novel pathways underlying different endotypes of CRS. We found significantly increased expression of G-CSF and IgG1 in highly neutrophilic CRS. G-CSF can stimulate the survival and function of neutrophils (37). A recent study showed that local IgG1 may lead to complement activation in CRSwNP (38), which in turn may promote the local recruitment of neutrophils via complement split products (39). Thus, it will be interesting to explore the contributions of G-CSF and IgG1 to the development of neutrophilic inflammation in CRS in the future.

Clusters 2 and 4 were composed of more CRSsNP patients compared with other clusters. Patients in cluster 7 had low levels of inflammation in the sinonasal mucosa despite the finding that the majority of these subjects were CRSwNP patients, which may resemble the “non-eosinophilic and non-neutrophilic CRSwNP” group proposed by Ikeda (40). Cluster 7 demonstrated the lowest symptom severity. Consistent with their mild inflammation, patients in these clusters had a moderate or low proportion of difficult-to-treat CRS.

Interestingly, in this study, we identified a novel small (4.1%) group of CRS patients characterized by high IL-10 levels. IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that is critical to limit and ultimately terminate immune and inflammatory responses (41). IL-10 levels have been found to negatively correlate with clinical symptoms in patients with house dust mite allergy (42). Despite the marked increase in levels of a number of inflammatory cytokines, this smallest cluster had no difficult-to-treat CRS, potentially due to the up-regulated IL-10. On the other hand, IL-10 expression was down-regulated in all other clusters, highlighting a potentially important role of IL-10, or the lack thereof, in the pathogenesis of CRS. The identification of this novel CRS endotype highlights the significance of our current cluster analysis since both CRSsNP and CRSwNP patients demonstrated down-regulated IL-10 expression as a whole group and this small group of patients has therefore heretofore been unrecognized. In this cluster, we still observed polyp development in most patients. Polyp formation may be due to remodeling factors not under the control of IL-10. This finding may indicate dissociation between inflammation and tissue remodeling in this subgroup of CRS (6, 43).

A further strength of this study is to characterize the difficult-to-treat CRS patients in the context of the identified subject clusters. Analyzing difficult and non-difficult cases in the whole CRS group, we could only identify an association of refractory cases with IL-10, eosinophilia, and IgE, but not neutrophilia. When performing the analysis within the different individual clusters however, we found that difficult-to-treat CRS was associated with different potential biomarkers in different clusters. For example, in cluster 3, difficult-to-treat CRS was associated with neutrophilic inflammation with up-regulation of IL-8 and IFN-γ; in cluster 7, difficult-to-treat CRS presented enhanced levels of IgG1–4. Therefore, these data reinforce the heterogeneous characteristic of CRS and further underline the importance of sub-classifying difficult-to-treat CRS patients that have diverse underlying pathophysiology.

Surprisingly, we found that non-difficult-to-treat CRS had a higher frequency of smoking exposure compared with difficult-to-treat CRS, which is contradictory to our perception of the negative effects of smoking on surgical outcomes of CRS (44). It may be due to the limitation of smoking recording in our study since we did not include consideration of passive smoking and did not have sufficient information to quantify the smoking severity.

This study has several limitations. Similar to previously published studies of cluster analysis of CRS (5, 6), the subjects in our study were those presenting to tertiary centers as surgical candidates after medical therapy had failed. More CRSwNP patients were enrolled than CRSsNP patients. Therefore, we must be cautious in extrapolating these findings to CRS in the general primary care population. Despite this caveat, clinicians usually pay more attention to patients ultimately referred to tertiary centers; the purpose of characterizing difficult-to-treat CRS patients is thus well served using our current subject recruitment strategy. In addition, given the immunopathologic differences discovered between Chinese and Caucasian patients, some of our findings may be limited to relevance in Chinese populations. However, comparing the difference between Chinese and white patients may provide novel insights into the pathogenesis of CRS. One potential criticism is that this is a single-center study and therefore our findings need to be replicated across multiple centers. Despite our efforts to be objective, there were several areas of subjectivity, including our selection of variables for clustering and our decisions on the number of clusters. We were unable to cover all the molecules critical for the pathogenesis of CRS due to the limited sample amount and technique limitation either. Nevertheless, we did not aim to get a termination for CRS classification but create a condition to study the internal mechanism and treatment prognosis of CRS as the best as we could. In this study, we evaluated subjective symptoms and disease severity by endoscopy and computed tomography examination. A more comprehensive assessment of quality of life, nasal resistance, and olfactory function would help to characterize CRS more precisely. Like other CRS cluster studies (5, 6), our current study does not address the question of stability in cluster membership It will be important to conduct longitudinal studies to evaluate the stability of clusters over time in relation to treatment and environmental changes in future. In addition, although power analysis showed the statistical power was greater than 0.8 in our study, our data should be interpreted with caution since the evaluation of a very large number of markers in a relatively modest numbers of subjects in some clusters might lead to statistical artifacts.

These comments notwithstanding, for the first time, we integrated multidimensional measurements in one unbiased cluster analysis to identify 7 CRS clusters with distinct endotypes and treatment outcomes. Our study emphasizes that both eosinophilic and neutrophilic inflammation can lead to poor outcomes under current steroid and surgery-centered treatment approaches and encourages the development of novel targeted therapies. Our clustering approach brings novel insights to CRS endotypes and difficult-to-treat CRS, highlighting the previously unrecognized importance of IL-10, G-CSF, and IgG1 in select groups of patients. In recent years, biologic agents targeting Th2 pathway and IgE, including humanized anti-IgE, anti-IL-5, and anti-IL-4 and IL-13 receptor antibody, have shown promising effects for the treatment of CRSwNP (45–47). It can be expected that cluster 1 is more likely to response to those treatments. In addition, the positive effects of IL-6 and IL-1β blocking on neutrophilic inflammation in arthritis and asthma highlight the possibility of targeting these cytokines for the treatment of CRS characterized by neutrophilic inflammation (48). Our study therefore provides an additional fundamental basis for identifying proper biomarkers to guide current and future biologic treatments for CRS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grants 81325006, 81570899 and 81630024 (Z.L.), 81200733 (H.W.), 81400448 (X.B.L.), 81700893 (B.L.) and 81400449 (P.P.C.), and Hubei Province Natural Science Foundation grant 2017CFA016 (Z.L.). Dr. Schleimer was supported in part by Grants R37HL068546 and U19AI106683 (Chronic Rhinosinusitis Integrative Studies Program (CRISP)) from the NIH, and by the Ernest S. Bazley Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure of conflict of interest: None

Authors’ Contribution

B.L. performed bio-plex study, statistical analysis, and prepared the manuscript. J.X.L., Z.Y.L. and Z.Z. collected the tissue samples and performed the bio-plex study. P.P.C., Y.Y., X.B.L. and H.W. participated in clinical data collection. Y.W. participated in data analysis and manuscript preparation. R.S. participated in data discussion and manuscript preparation. Z.L. designed the study and prepared the manuscript.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2012. Rhinology supplement. 2012;23:1–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:155–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao PP, Li HB, Wang BF, Wang SB, You XJ, Cui YH, et al. Distinct immunopathologic characteristics of various types of chronic rhinosinusitis in adult Chinese. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:478–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akdis CA, Bachert C, Cingi C, Dykewicz MS, Hellings PW, Naclerio RM, et al. Endotypes and phenotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis A PRACTALL document of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:1479–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soler ZM, Hyer JM, Rudmik L, Ramakrishnan V, Smith TL, Schlosser RJ. Cluster analysis and prediction of treatment outcomes for chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1054–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomassen P, Vandeplas G, Van Zele T, Cardell LO, Arebro J, Olze H, et al. Inflammatory endotypes of chronic rhinosinusitis based on cluster analysis of biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1449–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.12.1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lou H, Meng Y, Piao Y, Zhang N, Bachert C, Wang C, et al. Cellular phenotyping of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Rhinology. 2016;54:150–9. doi: 10.4193/Rhino15.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soler ZM, Hyer JM, Ramakrishnan V, Smith TL, Mace J, Rudmik L, et al. Identification of chronic rhinosinusitis phenotypes using cluster analysis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015;5:399–407. doi: 10.1002/alr.21496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakayama T, Asaka D, Yoshikawa M, Okushi T, Matsuwaki Y, Moriyama H, et al. Identification of chronic rhinosinusitis phenotypes using cluster analysis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:172–6. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Divekar R, Patel N, Jin J, Hagan J, Rank M, Lal D, et al. Symptom-based clustering in chronic rhinosinusitis relates to history of aspirin sensitivity and postsurgical outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3:934–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tokunaga T, Sakashita M, Haruna T, Asaka D, Takeno S, Ikeda H, et al. Novel scoring system and algorithm for classifying chronic rhinosinusitis: the JESREC Study. Allergy. 2015;70:995–1003. doi: 10.1111/all.12644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Veen J, Seys SF, Timmermans M, Levie P, Jorissen M, Fokkens WJ, et al. Real-life study showing uncontrolled rhinosinusitis after sinus surgery in a tertiary referral centre. Allergy. 2017;72:282–290. doi: 10.1111/all.12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang N, Van Zele T, Perez-Novo C, Van Bruaene N, Holtappels G, DeRuyck N, et al. Different types of T-effector cells orchestrate mucosal inflammation in chronic sinus disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122:961–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Zhang N, Bo Ms M, Holtappels G, Zheng M, Lou H, Wang H, Zhang L, Bachert C. Diversity of TH cytokine profiles in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis: A multicenter study in Europe, Asia, and Oceania. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1344–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao PP, Zhang YN, Liao B, Ma J, Wang BF, Wang H, et al. Increased local IgE production induced by common aeroallergens and phenotypic alteration of mast cells in Chinese eosinophilic, but not non-eosinophilic, chronic rhinosinustis with nasal polyps. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:690–700. doi: 10.1111/cea.12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, Bousquet J, Drazen JM, FitzGerald M, et al. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention: GINA executive summary. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:143–78. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00138707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Z, Lu X, Zhang XH, Bochner BS, Long XB, Zhang F, et al. Clara cell 10-kDa protein expression in chronic rhinosinusitis and its cytokine-driven regulation in sinonasal mucosa. Allergy. 2009;64:149–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund VJ, Mackay IS. Staging in rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 1993;31:183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S35–40. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu Y, Cao PP, Liang GT, Cui YH, Liu Z. Diagnostic significance of blood eosinophil count in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps in Chinese adults. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:498–503. doi: 10.1002/lary.22507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddel HK, Bateman ED, Becker A, Boulet LP, Cruz AA, Drazen JM, et al. A summary of the new GINA strategy: a roadmap to asthma control. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:622–39. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00853-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao B, Cao PP, Zeng M, Zhen Z, Wang H, Zhang YN, et al. Interaction of thymic stromal lymphopoietin, IL-33, and their receptors in epithelial cells in eosinophilic chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps. Allergy. 2015;70:1169–80. doi: 10.1111/all.12667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brasier AR, Victor S, Boetticher G, Ju H, Lee C, Bleecker ER, et al. Molecular phenotyping of severe asthma using pattern recognition of bronchoalveolar lavage-derived cytokines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:30–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.RE Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinks TS, Brown T, Lau LC, Rupani H, Barber C, Elliott S, et al. Multidimensional endotyping in patients with severe asthma reveals inflammatory heterogeneity in matrix metalloproteinases and chitinase 3-like protein 1. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Brightling CE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:218–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charrad M, Ghazzali N, Boiteau V, Niknafs A. NbClus: An R package for determining the relevant number of clusters in data set. J of Stat Softw. 2014;61:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–60. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourdin A, Molinari N, Vachier I, Varrin M, Marin G, Gamez AS, et al. Prognostic value of cluster analysis of severe asthma phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1043–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zoratti EM, Krouse RZ, Babineau DC, Pongracic JA, O’Connor GT, Wood RA, et al. Asthma phenotypes in inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1016–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens WW, Ocampo CJ, Berdnikovs S, Sakashita M, Mahdavinia M, Suh L, et al. Cytokines in chronic rhinosinusitis. Role in eosinophilia and aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:682–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2278OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gevaert P, Lang-Loidolt D, Lackner A, Stammberger H, Staudinger H, Van Zele T, et al. Nasal IL-5 levels determine the response to anti-IL-5 treatment in patients with nasal polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:1133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi LL, Xiong P, Zhang L, Cao PP, Liao B, Lu X, et al. Features of airway remodeling in different types of Chinese chronic rhinosinusitis are associated with inflammation patterns. Allergy. 2013;68:101–9. doi: 10.1111/all.12064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ebbens FA, Toppila-Salmi S, de Groot EJ, Renkonen J, Renkonen R, van Drunen CM, et al. Predictors of post-operative response to treatment a double blind placebo controlled study in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Rhinology. 2011;49:413–9. doi: 10.4193/Rhino10.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vlaminck S, Vauterin T, Hellings PW, Jorissen M, Acke F, Van Cauwenberge P, et al. The importance of local eosinophilia in the surgical outcome of chronic rhinosinusitis A 3-year prospective observational study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:260–4. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wen W, Liu W, Zhang L, Bai J, Fan Y, Xia W, Luo Q, et al. Increased neutrophilia in nasal polyps reduces the response to oral corticosteroid therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1522–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts AW. G-CSF: a key regulator of neutrophil production, but that's not all! Growth Factors. 2005;23:33–41. doi: 10.1080/08977190500055836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Roey GA, Vanison CC, Wu J, Huang JH, Suh LA, Carter RG, et al. Classical complement pathway activation in the nasal tissue of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Zele T, Coppieters F, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, Van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C. Local complement activation in nasal polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1753–8. doi: 10.1002/lary.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ikeda K, Shiozawa A, Ono N, Kusunoki T, Hirotsu M, Homma H, et al. Subclassification of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyp based on eosinophil and neutrophil. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:E1–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.24154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palomares O, Martin-Fontecha M, Lauener R, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Cavkaytar O, Akdis M, et al. Regulatory T cells and immune regulation of allergic diseases: role of IL-10 and TGF-β. Genes Immun. 2014;15:511–20. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Muller B, de Groot EJ, Kortekaas IJ, Fokkens WJ, van Drunen CM. Nasal epithelial cells express IL-10 at levels that negatively correlate with clinical symptoms in patients with house dust mite allergy. Allergy. 2007;62:1014–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Bruaene N, C PN, Van Crombruggen K, De Ruyck N, Holtappels G, Van Cauwenberge P, et al. Inflammation and remodeling patterns in early stage chronic rhinosinusitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:883–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katotomichelakis M, Simopoulos E, Tripsianis G, Zhang N, Danielides G, Gouma P, Bachert C, Danielides V. The effects of smoking on quality of life recovery after surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 2014;52:341–7. doi: 10.4193/Rhino13.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bachert C, Mannent L, Naclerio RM, Mullol J, Ferguson BJ, Gevaert P, et al. Effect of subcutaneous dupilumab on nasal polyp burden in patients with chronic sinusitis and nasal polyposis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:469–79. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bachert C, Sousa AR, Lund VJ, Scadding GK, Gevaert P, Nasser S, et al. Reduced need for surgery in severe nasal polyposis with mepolizumab: Randomized trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gevaert P, Calus L, Van Zele T, Blomme K, De Ruyck N, Bauters W, et al. Omalizumab is effective in allergic and nonallergic patients with nasal polyps and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:110–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hemandes ML, Mills K, Almond M, Todoric K, Aleman MM, Zhang H, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist reduces endotoxin-induced airway inflammation in healthy volunteers. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:379–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.