Abstract

Background

This study aims to evaluate the effect of transcatheter aortic valve (TAV) implantation depth and rotation on pressure gradient (PG), leakage fractions (LF), leaflet shear stress and sinus washout in an effort to understand factors that may dictate optimal positioning for valve-in-valve (ViV) procedures. Sinus flow stasis is often associated with prosthetic leaflet thrombosis. While recent ViV in-vitro studies highlighted transcatheter aortic valve (TAV) supra-annular implantation potential benefits to minimize pressure gradients, the relationship between TAV depth and other determinates of valve function remains unknown. Among these, LFs, shear stress and poor sinus washout have been associated with poorer valve outcomes.

Methods

ViV hemodynamic performance was evaluated in-vitro versus axial positions −9.8, −6.2, 0, and +6mm and angular orientations 0°, 30°, 60° and 90° in a degenerated SAV. PGs, LFs, and sinus shear stress and washout were compared. Leaflet high-speed-imaging and particle-image-velocimetry were performed to elucidate hemodynamic mechanisms.

Results

(a) The PG varies as a function of axial position, with supra-annular deployments yielding a maximum benefit of 7.85 mmHg less than PGs for sub-annular deployments irrespective of commissural alignment (p<0.01); (b) in contrast, LF decreased in relationship to sub-annular deployment; and (c) at peak systole, sinus flow shear stress increased with deployment depth as did sinus washout with and without coronary flow.

Conclusions

(a) Supra-annular axial deployment is associated with lower PGs irrespective of commissural alignment; (b) sub-annular deployment is associated with more favorable sinus hemodynamics, and less LF. Further in-vivo studies are needed to substantiate these observations and facilitate optimal prosthesis positioning during ViV procedures.

Transcatheter aortic valve (TAV) implantation inside a failed bioprosthetic surgical aortic valve (SAV) – also known as valve-in-valve (ViV) – offers an alternative to redo surgery for high-risk patients. However, elevated pressure gradients (PG) paravalvular leakage (PVL) and leaflet thrombosis can persist after ViV implantation and limit clinical effectiveness (1–4). To help understand and mitigate these events and better inform procedural technique, several studies have evaluated implantation depth and rotational orientation of the TAV with respect to the SAV as it pertains to post-implant PG. However, it remains to be established how various implant depths and rotational orientation affect other surrogates of valve function: PG, leakage fraction (LF) (an in-vitro correlate of PVL), shear stress and sinus flow stasis (in-vitro correlates for leaflet thrombosis).

Several studies have demonstrated that supra-annular deployment is associated with lower PGs, yet in some cases with higher LF (5–7). Commissural alignment (valve “rotation”) has been less well characterized, but to date has not been implicated in ViV hemodynamics (5–8). Despite a clinical preference for supra-annular deployment, elevated PGs (>20mmHg) do occur in about 15% of these cases, compared to 34% of sub-annular deployments (7). These observations suggest that there are other determinants of PG after VIV, and open the door to consider other surrogates of valve function when determining target implant depth.

Sinus flow dynamics are among additional features that may affect valve function and overall longevity. Decreased leaflet mobility after ViV implantation is likely caused by subclinical leaflet thrombosis (9,10), a phenomenon that has been linked to flow stasis (11–13). Although higher implants have been associated with more favorable PG, conflicting reports on their association with less sinus washout, and potentially a higher risk of flow stasis and thrombosis were published (14–17). Accordingly, a ViV implant that incorporates favorable hemodynamics in tandem with sinus washout may be optimal.

This study aims to evaluate the effect TAV depth and rotation on pressure gradient (PG), leakage fraction (LF), regional leaflet shear stress and sinus washout after ViV.

Material and Methods

High fidelity in-vitro measurements of Pressure gradients (PG), leakage fraction (LF), shear stress and sinus washout were performed, compared and analyzed for every valve configuration as described in detail below.

Valve selection and deployment

Using an aortic root model (Supplemental Fig. 1), a 23mm Medtronic Evolut TAV was implanted in a degenerated 23mm Carpentier-Edwards Perimount Magna SAV extracted from a patient who underwent a redo surgery. The TAV was deployed at 16 different combinations composed of 4 axial positions (+6. 0, 0, −6.2 and −9.8) and 4 angular rotations 0°, 30°, 60°, and 90°. Rotational orientation angle is the relative angular difference between the TAV and SAV commissures, with 0° representing complete commissural alignment (Fig. 1b to 1f).

Figure 1.

(a) Extracted calcified surgical aortic valve, (b,c,d,e) Schematic representation of axial deployment depths as seen by x-ray at +6mm, 0mm, −6.2mm and −9.8mm with a degenerated SAV respectively, (f) Angular orientations of the TAV in the SAV (g) Average PG variations versus axial positions for different angular orientations and (h) Average LFs variations versus axial positions for different angular orientations.

Hemodynamic assessment

PGs and LFs were evaluated under pulsatile flow conditions ensured by a left heart pulse duplicator yielding physiological flow and pressure curves(18,19). Base hemodynamics for all conditions were maintained with a systolic to diastolic pressure of 120/80mmHg, a 1 beat per second heart rate, a systolic duration of 33% and a cardiac output of 5l/min. The working fluid in this study was a mixture of water-glycerine (99% pure glycerine) producing a density of 1080 Kg/m3 and a kinematic viscosity of 3.5 cSt similar to blood properties. Sixty consecutive cardiac cycles of aortic pressure, ventricular pressure, and aortic flow rate data were recorded at a sampling rate of 100 Hz. The mean transvalvular pressure gradient (PG) was defined as the average of positive pressure difference between the ventricular and aortic pressure curves during forward flow. The average leakage fraction represents the ratio of the leakage volume (LV), without closing volume, to the total forward flow volume (FV) as follows:

| (1) |

High-speed imaging and Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV)

Videos of ViV en-face views were acquired throughout the cardiac cycle at 4000 frames/s to document the opening and closing dynamics of the leaflets using a Photron Fastcam SA3 high-speed video camera (Photron, San Diego, CA, USA) and a high-speed controller (HSC) (LaVision, Ypsilanti, MI).

For PIV, the flow was seeded with fluorescent PMMA-Rhodamine B particles with diameters ranging from 1 to 20 μm. For all ViV cases the velocity field within the sinus region including the region adjacent to the TAV leaflets were measured using high spatial and temporal resolution PIV. Briefly, this involved illuminating the sinus region using a laser sheet created by pulsed Nd:YLF single cavity diode pumped solid state laser coupled with external spherical and cylindrical lenses; while acquiring high-speed images of the fluorescent particles within the sinus region. Raw PIV images were acquired with and without coronary flow with a resulting spatial and temporal resolutions of 0.159mm/pixel and 4000 Hz respectively. Refraction was corrected using a calibration in DaVis particle image velocimetry software (DaVis 7.2, LaVision Germany). Velocity vectors were calculated using adaptive cross-correlation algorithms. Further details of PIV measurements can be found in Hatoum et al(12).

Sinus Vorticity and Shear Stress Dynamics

Using the velocity measurements from PIV, vorticity dynamics were also evaluated for the sinus region with and without coronary flow. Vorticity is the curl of the velocity field and therefore captures rotational components of the blood flow shearing(20). Regions of high vorticity along the axis perpendicular to the plane indicate both shear and rotation of the fluid particles. Out of plane vorticity in the z direction was computed using the following equation:

| (2) |

Where ωz is the vorticity component with units of s−1; Vx and Vy are the x and y components of the velocity vector with units of m/s. The x and y directions are axial and lateral respectively with the z direction being out of measurement plane.

Viscous shear stress field was evaluated consistently with Moore et al and Hatoum et al(19,21).

| (3) |

Where τ is the shear stress in Pascal (Pa) and μ is the dynamic viscosity in N.s/m2.

Sinus washout

Velocity measurements from PIV were also used to evaluate sinus washout. Sinus washout is defined as the characteristic curve representing the percent of fluid particles, initially seeded in the sinus region at the beginning of the cardiac cycle, and still remaining in the sinus as a function of time plotted over the cardiac cycle. Ideally good washout is associated with a high percentage of particles exiting over a minimum number of cardiac cycles. To quantify sinus washout curves, first particle tracking was performed similar to other studies (14–16). Briefly, particles were seeded as a uniform grid of 0.003m×0.003m cell size over the sinus region at the beginning of the cardiac cycle. Each particle’s trajectory was computed by integrating its velocity with respect to time based on:

| (4) |

With:

| (5) |

The integration time step was 0.00025s and at the end of every time step, the particle’s velocity vector was calculated based on the particle’s updated location through interpolating the PIV velocity data. After every cardiac cycle only the particles that remained in the sinus were re-seeded based on their last positions and their trajectory over the subsequent cardiac cycle was calculated. This process continued until all particles exited.

Once all the particles exited the sinus, a histogram of the time spent by the particles was generated and then converted to a cumulative distribution function representing the particles’ survival probability as a function of time. This procedure is repeated over 3 cycles for every valve combination. The resulting curves represent the sinus washout characteristic for all cases.

Results

A summary of hemodynamic results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average pressure gradient, peak pressure gradient and average leakage fractions for the different combinations of valve-in-valve.

| Axial Positions (mm) | Rotational Orientation | Average Pressure Gradient (mmHg) | Peak Pressure Gradient (mmHg) | Leakage Fractions (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +6 mm | 0° | 12.74±0.18 | 24.15±0.044 | 14.11±0.79 |

| 30° | 12.15±0.17 | 23.61±0.23 | 10.11±0.91 | |

| 60° | 12.41±0.17 | 29.7±0.060 | 9.02±0.84 | |

| 90° | 13.47±0.19 | 23.46±0.070 | 18.08±1.04 | |

| 0 mm | 0° | 17.55±0.24 | 26.53±0.27 | 11.19±0.43 |

| 30° | 13.16±0.18 | 24.35±0.075 | 9.57±0.10 | |

| 60° | 13.37±0.19 | 30.02±0.22 | 9.24±0.38 | |

| 90° | 17.60±0.24 | 28.9±0.015 | 10.20±0.26 | |

| −6.2 mm | 0° | 19.50±0.27 | 29.71±0.14 | 8.16±0.37 |

| 30° | 18.02±0.25 | 34.52±0.27 | 9.61±0.61 | |

| 60° | 18.44±0.26 | 35.51±0.13 | 8.15±0.56 | |

| 90° | 17.10±0.24 | 30.87±0.20 | 6.51±0.22 | |

| −9.8 mm | 0° | 15.81±0.22 | 32.65±0.11 | 8.07±0.22 |

| 30° | 17.44±0.24 | 37.93±0.25 | 10.79±0.57 | |

| 60° | 15.26±0.21 | 33.69±0.17 | 9.59±0.50 | |

| 90° | 20.05±0.28 | 35.58±0.07 | 13.97±0.44 |

a- Average PGs

Average PGs of different ViV axial positions and rotations are presented in Fig. 1g. For all rotational orientations, supra-annular deployment +6mm yields the lowest PGs compared with the other positions. The curves look similar as PG increases for axial locations of −9.8mm to −6.2mm then decreases as deployment is supra-annular at 0mm and +6mm. Angle 90° case shows an exception to this trend where the values of the PG increase slightly from 17.1±0.2 at −6.2mm to 17.6±0.2mmHg at 0mm, however the difference is insignificant (p=0.07). The curves also show that rotational orientation did not significantly change PG with the maximum differences being: 4.78mmHg at −9.8mm, 2.40mmHg at −6.2mm and 1.30mmHg at +6mm. Nevertheless, at 0mm, 30° and 60° were associated with lower PGs (p<0.01). The PG at +6mm with an angle of 90° is reported to be 13.5±0.2mmHg and that at −9.8mm with an angle of 60° is 15.3±0.2mmHg. The difference obtained between these 2 examples is 1.8mmHg. In the same manner, the PG at 0mm with aligned commissures (0°) is 17.6±0.2mmHg while at the same axial position with 60° the PG is 13.4±0.2mmHg. The difference is 4.2mmHg. The PG for a given axial position varied between 1.3mmHg and 4.8mmHg due to angular orientation variations. The pressure difference for a given angular position varied between 5.9mmHg and 6.8mmHg due to axial position changes.

b- Average LFs

Fig. 1h shows the average LFs of the different ViV rotational configurations versus axial positions. Supra-annular deployment (+6mm) yields the highest average LFs compared to other deployments irrespective of rotational orientation. At +6mm, the highest difference in LFs is 9.1% between 90° (highest) and 0° (lowest). At 0mm, −6.2mm, and −9.8mm these differences are 1.9%, 3.1% and 5.9% respectively. The curves show that for a particular angular orientation, axial positions cause differences in LFs. Only in models in which the TAV was considerably rotated (90°) was there a significant effect on LF with the deepest (−9.8mm), and highest (+6mm).

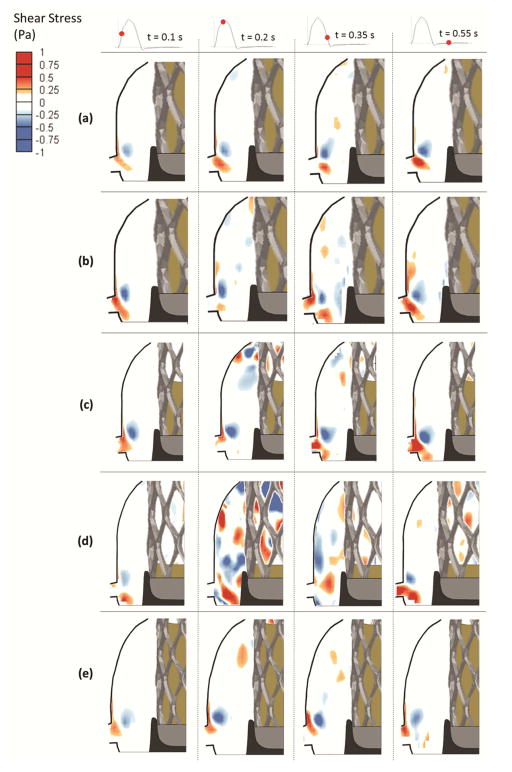

c- Shear Stress Distribution

Results summarizing sinus flow velocity and vorticity data are provided as Supplementary Material. Shear stress distributions was calculated at given time points for each ViV case. Results are presented as contour plots in Fig. 2 and 3 (with and without coronary flow, respectively). Sinus flow visualization is shown in Video 1. The region adjacent to the leaflet is of particular interest because low shear stress in this region may be associated with flow reduction and stasis(12). In Fig. 2, as deployment becomes sub-annular, shear stress patterns are more prevalent and their magnitudes increase. As peak systole is reached, the sinus region becomes more dominated by negative and positive shear stress regions. The magnitude of peak shear stress reaches 0.19Pa, 0.24Pa, 0.53Pa, and 0.78Pa at +6, 0, −6.2 and −9.8mm respectively. Shear stress patterns extend to the aortic side of the TAV leaflet. During late systole, shear stress magnitudes decrease to reach 0.18Pa, 0.17Pa, 0.33Pa, and 0.45Pa at +6, 0, −6.2 and −9.8mm respectively. During diastole, the largest shear stress exists only in the region near the ostium. The effect of TAV rotation on shear stress patterns was examined at the 0mm position, and patterns at the 60° angle are different than those with commissural alignment (0° rotation). At 60°, regions of negative and positive shear stress appear in the sinus during mid-systole mainly adjacent to the leaflets aortic side and the peak reaches 0.31Pa. During late systole, shear stress decreases to 0.19Pa. During diastole, the ostium side accommodates almost all the shear stress in the sinus region.

Figure 2.

Shear stress contours in the coronary sinus for (a) +6mm axial position, (b) 0mm axial position, (c) −6.2mm axial position, (d) −9.8mm axial position and (e) 0mm axial position and 60° angle.

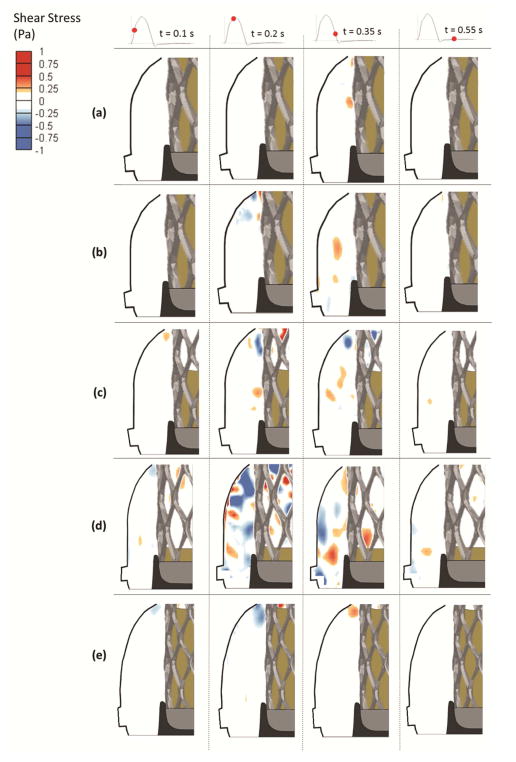

Figure 3.

Shear stress contours in the non-coronary sinus for (a) +6mm axial position, (b) 0mm axial position, (c) −6.2mm axial position, (d) −9.8mm axial position and (e) 0mm axial position and 60° angle.

In Fig. 3, similar to models in which coronary flow was simulated, as deployment becomes sub-annular shear stress patterns become more prevalent and their magnitudes increase. The main difference is that the presence of coronary flow drastically increases shear stress distribution. During early systole, regions with stronger shear stress is mainly obvious in the −6.2mm, the −9.8mm and the 0mm with 60° cases. As peak systole is reached, sinus region becomes more dominated by negative and positive shear stress concentrated mainly at the aortic side of the leaflet. Peak shear stress reaches 0.17Pa, 0.20Pa, 0.47Pa, and 0.65Pa at+6, 0, −6.2 and −9.8mm respectively. During late systole, shear stress decreases to reach 0.15Pa, 0.165Pa, 0.26Pa, and 0.33Pa at +6, 0, −6.2 and −9.8mm respectively. During diastole, stronger shear stress patterns are only evident in the −9.8 and −6.2mm cases.

Shear stress patterns for 0mm position case clearly differ during systole when comparing the 60° and 0° angle orientations. Specifically, for the 60 ° case, at the beginning of systole, shear stress is mainly localized near the sinotubular junction. During mid-systole mainly adjacent to the aortic side of the leaflet, the peak reaches 0.27Pa. During late-systole, shear stress decreases to 0.18Pa. During diastole, the patterns are similar between 0mm with 0°and 60°.

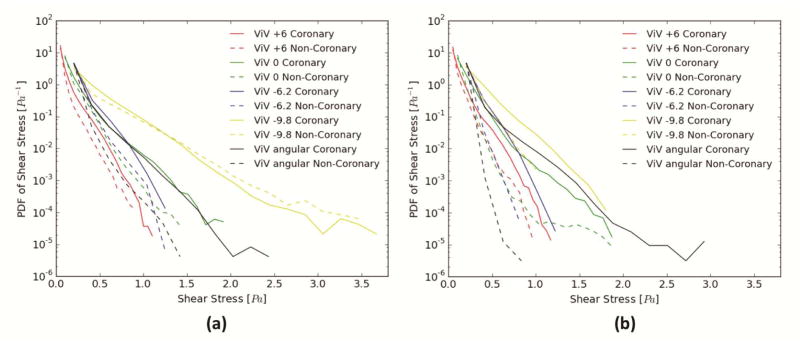

Fig. 4a and 4b presents the probability density function of shear stress magnitude in the subregion adjacent to the leaflet during systole and diastole. The value of the function represents the relative likelihood of occurrence (ordinate) for a shear stress magnitude (abscissa). In Fig. 4a, with coronary flow, ViV at −9.8mm shows relatively more occurrence of higher shear stress while ViV at +6mm shows the lowest occurrences of high shear stress. For shear stresses ranging between 0.5 and 1.0Pa, −6.2mm shows higher occurrences compared to 0mm with 0° and 60°. For shear stress above 1.0Pa, 0mm with 0° and 60° show higher likelihood, with the 60° angled ViV demonstrating an improvement over 0°. As expected, the presence of the coronary flow increases the likelihood of higher shear stress. Comparing with the non-coronary cases, −9.8mm again shows higher occurrences followed by −6.2mm, then 0mm with 0°, then 0mm with 60° then +6mm. In Fig. 4b, the upper limit of shear stress magnitude does not extend to more than 2.0Pa for all the ViV cases except for 0mm with 60° that reaches ~3.0Pa. With coronary flow, −9.8mm shows the highest occurrences of high shear stresses and +6mm shows the lowest. For shear stress between 0.5 and 0.8Pa, −6.2mm shows higher likelihood followed by 0mm (both 0° and 60°). For shear stresses greater than 0.8Pa, 0mm with 60° shows higher likelihood followed by 0mm with 0° then by −6.2mm. In the non-coronary cases, −9.8mm shows higher likelihood of greater shear stresses, followed by −6.2mm up to 0.5Pa, then 0mm with 60°, then 0mm with 0° and +6mm up to 0.6Pa. For shear stress magnitude greater than 0.5Pa, 0mm with 60° becomes the ViV combination with the least likelihood. For the shear stress ranging between 0.6 to 0.7Pa, +6mm shows higher probability of high shear stresses than −6.2mm and 0mm with 0°. 0mm with 0° probability again when shear stress exceeds 0.7Pa.

Figure 4.

Probability Density function in log scale of varying shear stress magnitude distribution values along a sub-region near the different ViV configurations leaflets during (a) systole and (b) diastole.

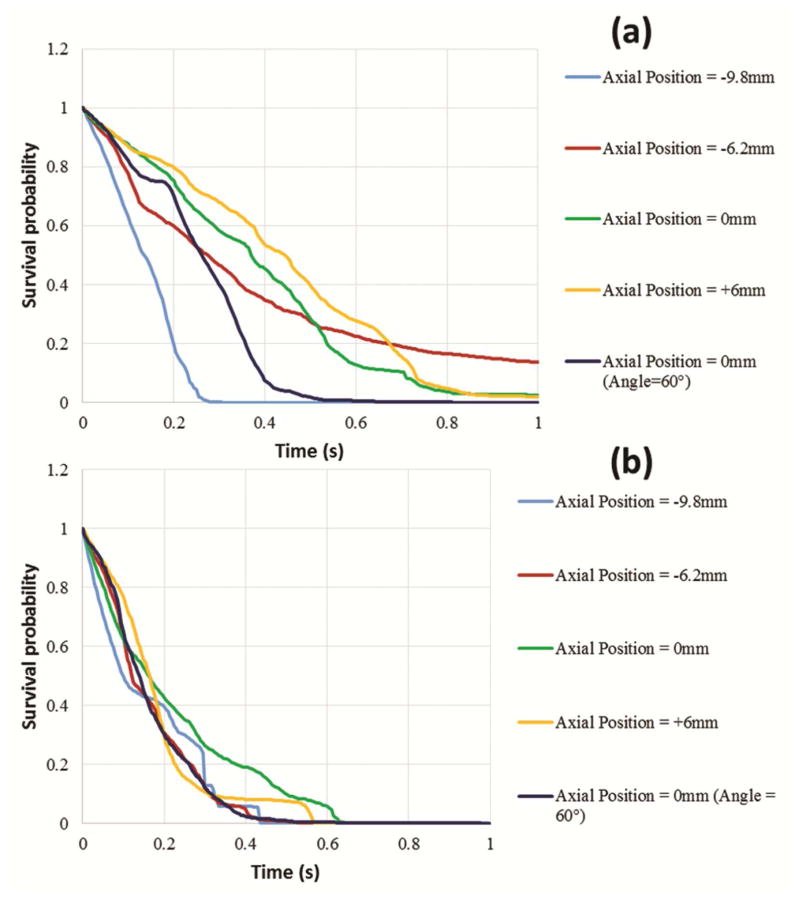

d- Sinus particles washout

Fig. 5a and 5b depict the sinus washout characteristic which shows the survival probability of the particles remaining inside the sinus region ensemble-averaged over 3 cardiac cycles for the non-coronary and coronary sinuses respectively. This is a measure of “sinus washout”, and represents the degree of flow stasis adjacent to the TAV leaflets. In Fig. 5a, the particles exit the sinus measurement plane completely after 0.28s for the −9.8mm case and 0.52s for 0mm with 60°-angle while it takes more than 1s for the particles to exit the sinus for −6.2mm (13.7% remain), 2.55% of the particles remain for 0mm and 1.97% remain for +6mm. 50% of particles exit the sinus at 0.135s, 0.275s, 0.26s, 0.445s, and 0.26s respectively at −9.8, −6.2, 0, +6, and 0 with 60°. −6.2mm shows faster washout for 50% of the particles and then exiting of the remaining particles becomes slower. In Fig. 5b, the presence of coronary flow significantly increases the washout. At 0.4s, all the particles in all cases have exited the sinus region except for the +6mm case where particles took 0.575s to exit and the 0mm with 0° case where particles took 0.635s to exit.

Figure 5.

Survival probability curve of particles remaining in the (a) non-coronary and the (b) coronary sinus regions for the different ViV axial positions ensemble averaged over 3 cardiac cycles.

Comment

The discussion is focused on how axial deployment and angular orientation in ViV affect various hemodynamic performance measures along with the aortic sinus hemodynamics and washout characteristics. These indices may likely be relevant to both individual patient outcomes, and perhaps long-term valve operation.

a- Effect of axial positions and angular orientations on PG

The results above lead to emphasizing the angular rotation for a particular axial position. Any change in angle, that is uncontrollable at the time of the procedure, leads to different PGs depending on the axial position. This shows that sub-annular deployments do not necessarily lead to higher PGs and worse ViV performance. In addition to the fact that supra-annular deployment is associated with lower PGs irrespective of commissural alignment. Rotational alignment may be an important factor at 0mm. At this axial position, the Evolut is almost aligned with the lowest margin of the SAV stent unlike the other axial depths. Given the calcium pattern alignment of the SAV may have an effect on the orifice generated once the TAV is deployed in the SAV at that position.

b- Effect of axial positions and angular orientations on LFs

The current results are in agreement with previous literature pointing out to the higher LFs observed when the TAV is deployed supra-annularly(6). This may be due to the minimal sealing provided to the TAV skirt and the loose grip of the SAV on the TAV. For instance, at +6mm when the commissures are aligned, the LF is 14.1±0.8% compared to 9.0±0.8% with 60° (p<0.01). Despite some superior results obtained by rotational orientation, at the time of the procedure it is not a controllable factor.

c- Effect of axial positions and angular orientations on sinus hemodynamics

In the assessment of leaflet thrombosis, we evaluated both sinus washout and shear stress near the TAV leaflets in accordance with previous publications(14,15). Although decreased washout in itself does not directly lead to thrombogenesis, once the clotting process is triggered (perhaps by blood contact with the foreign surfaces like a prosthetic valve), thrombosis is most likely to occur in low-flow regions characterized by longer particle/cell residence times(22,23). Similarly, reduced and oscillatory shear stresses have been linked to thrombosis(11,24).

Coronary flow presence alters shear stress pattern and increases its magnitude within a given sinus(12). Shear stress is higher with the sub-annular deployment and its patterns are more prevalent. Several studies have reported and classified shear stress values in grafts as “high” and “low” (25), and suggested low values of shear stress to be 0.25 Pa and 0.31 Pa while the high values were 1.54 Pa and 1.71 Pa. Another study of vascular shear stress by Cuningham et al(26) showed that vascular shear stress of large conduit arteries typically varies between 5 and 20 dynes/cm2 (0.5 to 2.0 Pa). Another study by Casa et al(27) reported a normal value of 1000 s−1 for shear rate that corresponds to 3.5 Pa in arteries and a value of 500 s−1 corresponding to 1.75 Pa in coronary arteries. A study by Bark et al(28) has reported physiological arterial shear rates below 400 s−1 equivalent to 1.4 Pa. Considering these thresholds, this gives sub-annular axial positions advantage and may account for the higher likelihood of leaflet thrombosis in non-coronary sinus leaflets. Fig. 4 clearly shows how the presence of the 60°angle in ViV improves shear stress and yields higher magnitudes and wider ranges of shear stress values. This gives commissural rotational orientation advantage over having the commissures aligned. While rotational alignment is not currently controllable, it would certainly be advantageous for future generation TAVs to enable such control. The figure also shows in a quantitative sense the advantage of sub-annular deployment compared to supra-annular deployment when it comes to sinus flow stasis.

d- Effect of axial positions and angular orientations on sinus washout

Particle tracking analysis performed on every ViV case revealed that sub-annular deployment yields better and faster washout of blood within the sinus compared to the supra-annular positions. This highlights the sub-annular depths’ advantage in ViV (100% enhancement between −9.8 and+6mm). In addition, this shows the improvement achieved with angular orientation (100% enhancement between 0mm with 0° and 60°) in the non-coronary sinus. The leaflet oscillations observed in the supra-annular deployment cases in Video 2 induce some benefits in terms of “pumping” the sinus fluid out of the sinus region during the cardiac cycle. This helps explain why at particular points, some supra-annular cases show better washout compared with −6.2mm ViV case. This particular position is characterized by the leaflet occupying half of the sinus region which impacts the locations of the vortices formed along with the magnitudes and patterns of the flow. Coronary flow drastically improves sinus washout independently of any axial or angular position. However, the sub-annular deployment cases and the addition of an angle for one of the supra-annular deployment cases provided a faster washout.

Limitations

The use of a rigid sinus chamber is not physiological. However, this limitation outweighs the benefits of high-resolution flow studies within the sinus region. The experiments were conducted using a single Medtronic Evolut TAV 23 deployed in a stented SAV that is the degenerated Carpentier-Edwards Magna 23. While degeneration patterns are unique to each patient, this study illustrates the complexity of hemodynamics and flow patterns that may be expected.

Conclusion

A comprehensive in-vitro study to understand the integrative mechanisms dictating ViV performance using a degenerated surgical valve was performed with a Medtronic Evolut as the TAV as a function of axial positions and angular orientations. This study showed that (a) supra-annular axial deployment clearly possesses advantages of achieving lower PGs; (b) sub-annular axial deployment enhances sinus washout and sinus flow shear stress. Further insight about the appropriate balance is needed from in-vivo studies.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Eggebrecht H, Schäfer U, Treede H, et al. Valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve implantation for degenerated bioprosthetic heart valves. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2011;4:1218–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dvir D, Webb J, Brecker S, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement for degenerative bioprosthetic surgical valves: results from the global valve-in-valve registry. Circulation. 2012 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.104505. CIRCULATIONAHA. 112.104505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leetmaa T, Hansson NC, Leipsic J, et al. Early Aortic Transcatheter Heart Valve Thrombosis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2015;8:e001596. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.114.001596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Córdoba-Soriano JG, Puri R, Amat-Santos I, et al. Valve thrombosis following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2015;68:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Azadani AN, Jaussaud N, Ge L, Chitsaz S, Chuter TA, Tseng EE. Valve-in-valve hemodynamics of 20-mm transcatheter aortic valves in small bioprostheses. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011;92:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonato M, Azadani AN, Webb J, et al. In vitro evaluation of implantation depth in valve-in-valve using different transcatheter heart valves. EuroIntervention: journal of EuroPCR in collaboration with the Working Group on Interventional Cardiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2016;12:909. doi: 10.4244/EIJV12I7A149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonato M, Webb J, Kornowski R, et al. Transcatheter Replacement of Failed Bioprosthetic Valves. Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2016;9:e003651. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.003651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Midha PA, Raghav V, Condado JF, et al. Valve Type, size, and deployment location affect hemodynamics in an in vitro valve-in-valve model. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2016;9:1618–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakravarty T, Søndergaard L, Friedman J, et al. Subclinical leaflet thrombosis in surgical and transcatheter bioprosthetic aortic valves: an observational study. The Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makkar RR, Fontana G, Jilaihawi H, et al. Possible subclinical leaflet thrombosis in bioprosthetic aortic valves. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:2015–2024. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1509233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasi LP, Hatoum H, Kheradvar A, et al. On the Mechanics of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2016:1–22. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1759-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatoum H, Moore BL, Maureira P, Dollery J, Crestanello JA, Dasi LP. Aortic sinus flow stasis likely in valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve implantation. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatoum H, Crestanello J, Dasi LP. Possible Subclinical Leaflet Thrombosis in Bioprosthetic Aortic Valves. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374:1590–1592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1600179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Midha PA, Raghav V, Okafor I, Yoganathan AP. The Effect of Valve-in-Valve Implantation Height on Sinus Flow. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1642-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar G, Raghav V, Lerakis S, Yoganathan AP. High Transcatheter Valve Replacement May Reduce Washout in the Aortic Sinuses: an In-Vitro Study. The Journal of heart valve disease. 2015;24:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vahidkhah K, Azadani AN. Supra-annular Valve-in-Valve implantation reduces blood stasis on the transcatheter aortic valve leaflets. Journal of Biomechanics. 2017;58:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2017.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Midha PA, Raghav V, Sharma R, et al. The Fluid Mechanics of Transcatheter Heart Valve Leaflet Thrombosis in the Neo-Sinus. Circulation. 2017 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029479. CIRCULATIONAHA. 117.029479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forleo M, Dasi LP. Effect of hypertension on the closing dynamics and lagrangian blood damage index measure of the B-Datum Regurgitant Jet in a bileaflet mechanical heart valve. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2014;42:110–122. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0896-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hatoum H, Moore BL, Maureira P, Dollery J, Crestanello JA, Dasi LP. Aortic sinus flow stasis likely in valve-in-valve transcatheter aortic valve implantation. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.03.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bapat V. Valve in Valve app. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore BL, Dasi LP. Coronary flow impacts aortic leaflet mechanics and aortic sinus hemodynamics. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2015;43:2231–2241. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1260-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rayz V, Boussel L, Ge L, et al. Flow residence time and regions of intraluminal thrombus deposition in intracranial aneurysms. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2010;38:3058–3069. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0065-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gorbet MB, Sefton MV. Biomaterial-associated thrombosis: roles of coagulation factors, complement, platelets and leukocytes. Biomaterials. 2004;25:5681–5703. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandra S, Rajamannan NM, Sucosky P. Computational assessment of bicuspid aortic valve wall-shear stress: implications for calcific aortic valve disease. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology. 2012;11:1085–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10237-012-0375-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu M, Kouchi Y, Onuki Y, et al. Effect of differential shear stress on platelet aggregation, surface thrombosis, and endothelialization of bilateral carotid-femoral grafts in the dog. Journal of vascular surgery. 1995;22:382–90. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70005-6. discussion 390–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunningham KS, Gotlieb AI. The role of shear stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Laboratory investigation. 2005;85:9–23. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casa LD, Deaton DH, Ku DN. Role of high shear rate in thrombosis. Journal of vascular surgery. 2015;61:1068–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bark DL, Para AN, Ku DN. Correlation of thrombosis growth rate to pathological wall shear rate during platelet accumulation. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 2012;109:2642–2650. doi: 10.1002/bit.24537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.