Abstract

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a chronic yet progressive myeloid neoplasm in which only a minority of patients undergo curative therapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, is the lone therapy approved for MF, offering a clear symptom and spleen benefit at the expense of treatment-related cytopenias. Pacritinib (PAC), a multi-kinase inhibitor with specificity for JAK2, FLT3, and IRAK1 but sparing JAK1, has demonstrated clinical activity in MF with minimal myelosuppression. Due to an FDA-mandated full clinical hold, the randomized phase 3 PERSIST trials were abruptly stopped and PAC was immediately discontinued for all patients. Thirty-three patients benefitting from PAC on clinical trial prior to the hold were allowed to resume therapy on an individual, compassionate-use basis. This study reports the detailed outcomes of 19 of these PAC retreatment patients with a median follow-up of 8 months. Despite a median platelet count of 49 × 109/L at restart of PAC, no significant change in hematologic profile was observed. Grade 3/4 adverse events of epistaxis (n=1), asymptomatic QT prolongation (n=1) and bradycardia (n=1) occurred in 3 patients within the first 3 months of re-treatment. One death due to catheter associated sepsis occurred. The median time to discontinuation of PAC therapy on compassionate use for all 33 patients was 12.2 (95% CI: 8.3 - NR) months. PAC retreatment was associated with modest improvement in splenomegaly without progressive myelosuppression and supports the continued development of this agent for the treatment of MF second line to ruxolitinib or in the setting of treatment-limiting thrombocytopenia.

Keywords: Myelofibrosis, pacritinib, JAK inhibitor

Background

Myelofibrosis (MF) is a clonal hematopoietic malignancy characterized by progressive splenomegaly, debilitating systemic symptoms, and limiting cytopenias often requiring transfusion support (1). Hyperactivity of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway is the unifying pathobiological theme of this molecularly heterogeneous disease (2). Ruxolitinib (Jakafi, Incyte) is the only therapy approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for MF, and the majority of patients benefit from symptom improvement and spleen reduction, at the expense of myelosuppression (3, 4). Although ruxolitinib was a major milestone in drug development for MF, this therapy does not effectively induce pathologic and molecular remissions, and therefore, disease progression can occur in treated patients (5). Outcomes in this population are dismal with a median survival after ruxolitinib discontinuation of 14 months, and even worse for those with a platelet count <100 × 109/L at the time of discontinuation (6).

Pacritinib (CTI Biopharma) is an oral multi-kinase inhibitor with selectivity against JAK2, FLT3, and IRAK1 (7). Pacritinib (PAC) was evaluated in two multi-centered, randomized, phase 3 trials in patients with advanced myelofibrosis (MF). The PERSIST-1 trial enrolled patients with MF irrespective of baseline platelet count and without previous exposure to ruxolitinib (8). These patients were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to PAC 400 mg daily versus best available therapy (BAT), excluding ruxolitinib. The primary endpoint of 35% or greater spleen volume reduction (SVR) at 24 weeks of therapy was superior in the PAC arm compared to BAT, 19.1% versus 4.7%. The PERSIST-2 trial included MF patients with baseline thrombocytopenia (<100 × 109/L) and palpable splenomegaly and compared PAC at doses of 200 mg twice daily and 400 mg once daily to BAT including ruxolitinib (9). The co-primary endpoints of SVR and total symptom score (TSS) reduction for the combined PAC twice daily and once daily arms compared to BAT were not significant (p=0.001 for SVR and 0.079 for TSS) but were significant when assessing the PAC 200 mg twice daily cohort compared to BAT, (SVR: 21.6% vs 2.8%; p<0.007 and TSS: 32.4% vs 13.9%, p<0.011).

On February 9, 2016, a full clinical hold was placed on PAC due to concerns by the FDA surrounding an OS detriment focused on increased bleeding and cardiovascular events based upon the interim analyses of PERSIST-2 and consistent with the results from PERSIST-1. Shortly after the full hold order, the FDA allowed patients who were benefiting from PAC therapy, based on investigator assessment, to enroll in single patient compassionate use protocols. The hold was lifted on January 5, 2017 after review of the complete data set from PERSIST-2 and on acceptance of a dose searching protocol (PAC 203; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03165734) for patients with MF who failed to benefit from ruxolitinib.

Due to this hold, immediate cessation of PAC therapy was mandated for all patients enrolled on clinical trials. This abrupt discontinuation of PAC therapy prevented appropriate study follow up, and the experience of patients that resumed PAC on a compassionate care (CC) basis has not been reported. We conducted a sponsor-independent analysis of the outcomes of patients treated with CC-PAC after withdrawal from therapy on clinical trial.

Methods

This study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and each participating center obtained approval from their institutional review board prior to data collection. Only patients enrolled in the CC-PAC single patient investigational new drug (IND) program through the FDA were included in this retrospective study. Patients treated with CC-PAC were additionally required to be monitored for bleeding and cardiac treatment emergent adverse events at baseline and every three months on therapy with a complete blood count, coagulation profile, electrocardiogram and echocardiogram (or multi-gated acquisition scan). The local treating physician provided the requested data in a paper case report form (CRF) and this was entered centrally (Mount Sinai) into an electronic database. Additional analysis to determine the probability of remaining on CC-PAC were performed on the de-identified follow-up data of the entire cohort of patients treated on the compassionate care program. This data was provided courtesy of CTI Biopharma but analyzed independently by the authors.

Statistical analyses were performed with the SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) software package. Continuous patient-related, disease-related, and treatment-related variables were summarized by median [Q1–Q3] while categorical variables were summarized by N (%). The method of Kaplan-Meier was used to estimate the overall survival (OS), follow-up and CC-PAC exposure distributions while taking into account censored observations. Linear mixed models of natural log transformed lab values (WBC, hemoglobin, platelet and spleen length) were used to compare geometric means of values over time.

Results

CRFs were completed on a total of 19 of 33 patients receiving CC-PAC from 7 centers in 2 countries (U.S. and New Zealand). The baseline demographics of these patients at the start of initial PAC therapy on the PERSIST clinical trial program are shown in Table 1. This was predominantly an advanced MF population with splenomegaly and a measurable symptom burden by the TSS. Approximately 20% of PAC treated patients at baseline had received previous ruxolitinib therapy and 40% were red blood cell transfusion-dependent.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics at Entry on PERSIST-2, N=19

| Age, median [q1–q3] | 71 [64–74] |

|

| |

| Male | 10 (53%) |

|

| |

| MF Diagnosis | |

| Primary-MF | 11 (58%) |

| PPV-MF | 6 (32%) |

| PET-MF | 2 (11%) |

|

| |

| Genotype | |

| JAK2V617F positive | 11 (58%) |

| MPLW515L/K | 1 (5%) |

| CALR Exon 9 Insertion/Type 1 | 1 (5%) |

| CALR Exon 9 Insertion/Type 2 | 0 (0%) |

| Triple Negative | 6 (32%) |

|

| |

| % VAF, median [q1–q3] | 36.6 [8.0–50.0] |

|

| |

| Number of MF Directed Therapies prior to Pacritinib, median [q1–q3] | 1 [1-1] |

|

| |

| Received Prior Ruxolitinib | 4 (21%) |

|

| |

| Duration of Ruxolitinib therapy (months), median [q1–q3] | 7.5 [2–18] |

|

| |

| Transfusion Dependent Prior to pacritinib | |

| Yes | 7 (37%) |

| No | 11 (58%) |

| Unknown | 1 (5%) |

|

| |

| WBC (103/μl), median [q1–q3] | 6.9 [3.4–15.0] |

|

| |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), median [q1–q3] | 10.2 [8.7–11.3] |

|

| |

| Platelet (103/μL), median [q1–q3] | 49.0 [33.0–85.0] |

|

| |

| Spleen length by palpation (cm), median [q1–q3] | 14.0 [9.0–18.0] |

|

| |

| TSS, median [q1–q3] | 15.6 [8.6–23.4] |

|

| |

| DIPSS risk category | |

| Int-1 | 4 (21%) |

| Int-2 | 9 (47%) |

| High | 5 (26%) |

| Unknown | 1 (5%) |

Range: [q1 q3]

Data expressed as n (%) unless otherwise stated

The median duration of PAC therapy on clinical trial prior to the clinical hold was 8.5 months (range, 3.6–11.1). A median duration of 4 months (range, 1.8–14.8) occurred between stopping PAC on clinical trial due to the FDA hold and initiating CC-PAC. Five of the 19 patients received an alternative MF therapy in the interim prior to starting CC-PAC [ruxolitinib 5 mg twice daily n=2; hydroxyurea n=2, decitabine n=1].

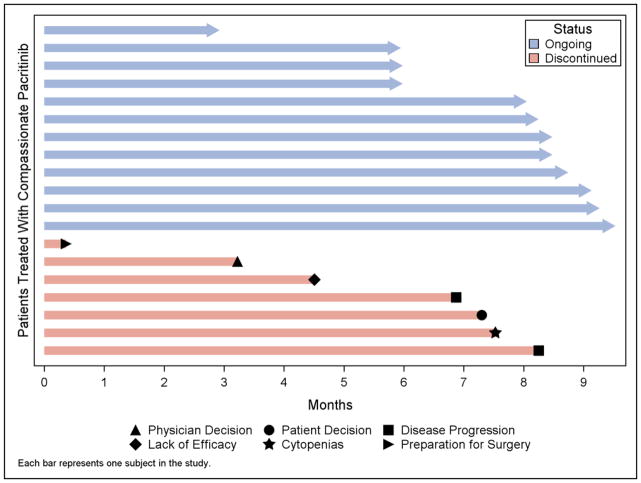

The baseline demographics of these patients at the start of CC-PAC therapy are shown in Table 2. All 19 patients included in this analysis received CC-PAC at 200mg BID. The median duration of follow up in this CC-study was 8 months (range, 3–9.5), and median duration of CC-PAC exposure was 8 months (range, 0.4–9.5). This was computed as months to stopping CC-PAC therapy (either by completing full 9 months or discontinuing prior to 9 months). Patients were censored if they were not followed for full 9 months of study either because they started therapy less than 9 months ago or were lost to follow up (Figure 1; Table 5).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographics at Entry on Compassionate Care Pacritinib, N=19

| Interim MF Directed Therapies | |

| Yes | 5 (26%) |

| No | 14 (74%) |

|

| |

| WBC (103/μl), median [q1–q3] | 6.2 [3.2–17.6] |

|

| |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), median [q1–q3] | 9.9 [8.7–12.2] |

|

| |

| Platelet (103/μL), median [q1–q3] | 49.0 [37.0–63.0] |

|

| |

| Spleen length by palpation (cm), median [q1–q3] | 15.0 [8.0–18.0] |

|

| |

| Ejection Fraction%, median [q1–q3] | 62 [59–65] |

|

| |

| Transfusion Dependent | |

| Yes | 9 (47%) |

| No | 10 (53%) |

Range: [q1–q3]

Data expressed as n (%) unless otherwise stated

Figure 1. Duration of Pacritinib Treatment on Compassionate Care Program and Reasons for Discontinuation.

Duration of treatment in months for the 19 individual patients detailed in this report. Patients remaining on treatment at the time of this analysis and patients that had discontinued are indicated by color and the reasons for discontinuation are shown in the key.

Table 5.

Overall Survival and Duration of Compassionate Care Pacritinib Exposure, N=19

| Overall Survival | |

| Deaths, n (%) | 1 (5%) |

| 9-month survival probability (95% CI) | 0.94 (0.63, 0.99) |

| CC-PAC Exposure | |

| Discontinued CC-PAC therapy within 9 months*, n (%) | 7 (37%) |

| Completed CC-PAC therapy 9 months, n (%) | 6 (31.5%) |

| Censored for CC-PAC exposure, n (%) | 6 (31.5%) |

| Median CC-PAC Exposure in months (95% CI) | 8.3 (6.9–9.1) |

discontinued Pacritinib by 9 months of start of PAC Compassionate Care for any reason

There was a significant difference between mean palpable spleen length at month 3 (11.3 cm) and 6 (12.1 cm) compared to baseline (14.3 cm) [p=0.0009]. At 6 months of therapy in 15 patients, there was no significant change from baseline in hematologic parameters (Table 3). At months 3, 6, and 9 there were 44%, 47%, and 50% of patients, respectively, experiencing at least one treatment emergent adverse event regardless of attribution and these were almost exclusively grade 1/2 (Table 4). Three patients experienced grade 3 adverse events of epistaxis, QT prolongation, and bradycardia. There were no clinically significant treatment emergent changes in echocardiogram findings in any of the treated patients.

Table 3.

Hematologic and spleen parameters over time on Compassionate Care Pacritinib, N=19

| Baseline | 3 Months | 6 Months | 9 Months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N=19 | N=17 | N=15 | N=6 | |

|

| ||||

| WBC (103/μl) | ||||

| Median[q1–q3] | 6.2 [3.2–17.6] | 7.8 [4.3–9.5] | 8.0 [4.3–15.4] | 8.1 [1.5–26.5] |

| Min-Max | 1.1–102.6 | 1.0–21.1 | 1.2–51.2 | 1.3–31.9 |

| Mean [SD]* | 8.3 (3.2) | 6.5 (2.1) | 7.0 (2.8) | 6.9 (3.9) |

|

| ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/DL) | ||||

| Median[q1–q3] | 9.9 [8.7–12.2] | 10.1 [8.5–11.7] | 9.9 [8.7–12.5] | 12.3 [9.7–14.0] |

| Min-Max | 7.4–15.6 | 6.3–14.3 | 8.1–14.3 | 8.0–14.1 |

| Mean [SD]* | 10.1 (1.2) | 9.8 (1.3) | 10.3 (1.2) | 11.5 (1.3) |

|

| ||||

| Platelet (103/μL) | ||||

| Median[q1–q3] | 49.0 [37.0–63.0] | 49.0 [39.0–103.0] | 57.0 [34.0–118.0] | 62.5 [40.0–105.0] |

| Min-Max | 19.0–312.0 | 17.0–287.0 | 23.0–245.0 | 19.0–194.0 |

| Mean [SD]* | 54.1 (2.0) | 59.1 (2.2) | 60.9 (2.1) | 62.2 (2.2) |

|

| ||||

| Spleen length by palpation (cm) | ||||

| N | 19 | 14 | 12 | 4 |

| Median[q1–q3] | 15.0 [8.0–18.0] | 11.0 [7.0–17.0] | 13.5 [7.0–17.0] | 17.0 [8.0–20.5] |

| Min-Max | 0–36 | 0–24 | 0–23 | 0–23 |

| Mean (SD) | 14.3 (8.4) | 11.4 (6.7) | 12.1 (7.2) | 14.3 (9.9) |

Data expressed as median [range] unless otherwise stated; range: [q1–q3]

Geometric Mean and SD provided due to skewness of distribution and inappropriate use of arithmetic mean

Table 4.

Treatment-Emergent Adverse Events of Interest on Compassionate Care Pacritinib by grade, N=181

| At Any Grade | At Grade 3 or 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| All events | 10 (56%) | 3 (17%) |

| Bleeding events | 3 (17%) | 1 (6%) |

| Epistaxis | 2 (11%) | 1 (6%) |

| Hematemesis | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cardiovascular events | 2 (11%) | 2 (11%) |

| QT Prolongation | 1 (6%) | 1 (6%) |

| Bradycardia2 | 1 (6%) | 1 (6%) |

| Assessment Period | ||

| 3-month events (N=18) | 8 (44%) | 3 (17%) |

| 6-month events (N=15) | 7 (47%) | 0 (0%) |

| 9-month events (N=6) | 3 (50%) | 0 (0%) |

one patient did not have AEs evaluated yet

with premature atrial contractions

Data expressed as # (%) of patients experiencing at least 1 AE overall and at each assessment

Seven patients discontinued treatment with CC-PAC for reasons that included: sepsis/death (n=1), disease progression/acute myeloid leukemia (n=2), lack of efficacy (n=1), surgery for ovarian cancer (n=1), patient decision (n=1), and physician decision (n=1). There were no dose holds or modifications while on CC-PAC. One patient died while on CC-PAC from complications of a central line associated bacterial infection. The 9-month probability of survival was 94% (CI, 63–99%).

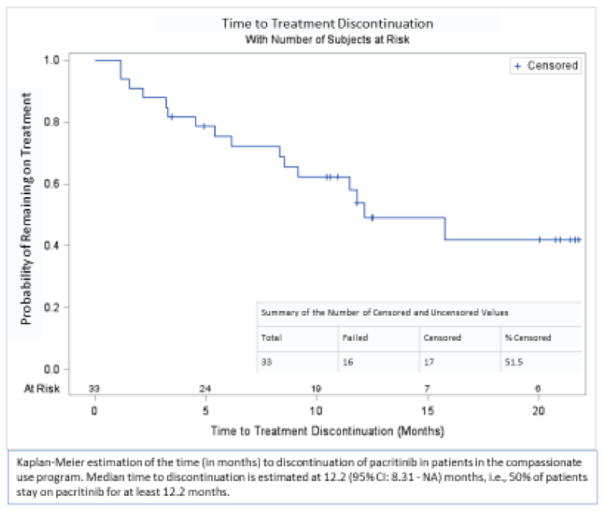

Duration of treatment was available for the entire cohort of 33 patients treated on the compassionate use protocol (Courtesy of CTI Biopharma). Median time to discontinuation of CC-PAC was 12.2 (95% CI: 8.3 - NR) months. The probability of remaining on CC-PAC at 6, 12, and 18 months was 75%, 54%, and 42%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimation of the Time to Discontinuation of Pacritinib in Patients in the Compassionate Use Program.

Median time to discontinuation is estimated at 12.2 (95% CI: 8.31 – NA) months in 33 patients receiving pacritinib on a compassionate basis after initially stopping pacritinib treatment on clinical trial due

Discussion

PAC therapy is associated with spleen and symptom improvement in patients with MF regardless of prior ruxolitinib treatment (PERSIST-2), and subset analyses of this prior ruxolitinib exposure population confirms activity in these patients (manuscript in preparation). This analysis of the outcomes of patients previously treated with PAC on clinical trial, who were then transitioned to compassionate use after mandatory study discontinuation, is the first report of the real-world experience of PAC therapy in MF. In a population of patients with advanced MF, the current study did not identify any significant treatment-emergent adverse events. Moreover, there was modest improvement in palpable spleen length over the duration of CC-PAC treatment. The median time on PAC for the full 33 patients treated on the compassionate care protocol was approximately 1 year, with 42% still on treatment for over 18 months. Despite PAC treatment interruption of a median of 4 months, and a median PAC treatment on clinical trial of 8.5 months, half the patients continued to receive PAC treatment for an additional 12 months on CC-PAC. This corresponds to approximately 24 months (20 months of cumulative PAC therapy) since start of PAC on clinical trial which appears favorable compared to the reported median survival of 14 months after ruxolitinib discontinuation (6).

Limitations of this retrospective study include short follow up, absence of standardized patient reported outcome (PRO) for symptom burden and objective radiographic assessment of change in spleen volume. There were also significant gaps between treatment on trial and the start CC-PAC. It is unclear how this interruption in JAK inhibitor therapy may have affected efficacy of PAC and the overall outcomes in this analysis. Additionally, the inclusion of a control population of patients that discontinued PAC therapy on clinical trial and then received alternative agents to CC-PAC would have allowed for a relevant comparator of outcomes. Nevertheless, PAC was well tolerated in the CC setting and significant bleeding events were uncommon with only a single patient experiencing grade 3 epistaxis. These results demonstrate safety and efficacy of PAC outside of a formal clinical trial context and confirm the unmet need for PAC in patients with MF and thrombocytopenia where alternative therapeutic options including ruxolitinib are limited.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Biostatistics Shared Resource Facility, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA196521-0 and assistance from Jack Singer, Kris Kanellopoulos, Tanya Granston, Lixia Wang.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hoffman R, Rondelli D. Biology and treatment of primary myelofibrosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2007:346–54. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mascarenhas JO, Cross NC, Mesa RA. The future of JAK inhibition in myelofibrosis and beyond. Blood Rev. 2014 Sep;28(5):189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison C, Kiladjian JJ, Al-Ali HK, Gisslinger H, Waltzman R, Stalbovskaya V, et al. JAK inhibition with ruxolitinib versus best available therapy for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 1;366(9):787–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verstovsek S, Mesa RA, Gotlib J, Levy RS, Gupta V, DiPersio JF, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ruxolitinib for myelofibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012 Mar 1;366(9):799–807. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervantes F, Pereira A. Does ruxolitinib prolong the survival of patients with myelofibrosis? Blood. 2017 Feb 16;129(7):832–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-731604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newberry KJ, Patel K, Masarova L, Luthra R, Manshouri T, Jabbour E, et al. Clonal evolution and outcomes in myelofibrosis after ruxolitinib discontinuation. Blood. 2017 Aug 31;130(9):1125–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-783225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hart S, Goh KC, Novotny-Diermayr V, Hu CY, Hentze H, Tan YC, et al. SB1518, a novel macrocyclic pyrimidine-based JAK2 inhibitor for the treatment of myeloid and lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia. 2011 Nov;25(11):1751–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mesa RA, Vannucchi AM, Mead A, Egyed M, Szoke A, Suvorov A, et al. Pacritinib versus best available therapy for the treatment of myelofibrosis irrespective of baseline cytopenias (PERSIST-1): an international, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2017 May;4(5):e225–e36. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30027-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mascarenhas J, Hoffman R, Talpaz M, et al. Pacritinib vs best available therapy, including ruxolitinib, in patients with myelofibrosis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncology. 2018 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]