Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is characterized by pulmonary arterial remodeling that results in increased pulmonary vascular resistance, right ventricular (RV) failure, and premature death. Down-regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) in the pulmonary vasculature leads to perturbations in calcium ion (Ca2+) homeostasis and transition of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells to a proliferative phenotype.

OBJECTIVES

We assessed the feasibility of sustained pulmonary vascular SERCA2a gene expression using aerosolized delivery of adeno-associated virus type 1 (AAV1) in a large animal model of chronic PH and evaluated the efficacy of gene transfer regarding progression of pulmonary vascular and RV remodeling.

METHODS

A model of chronic post-capillary PH was created in Yorkshire swine by partial pulmonary vein banding. Development of chronic PH was confirmed hemodynamically, and animals were randomized to intratracheal administration of aerosolized AAV1 carrying the human SERCA2a gene (n = 10, AAV1.SERCA2a group) or saline (n = 10). Therapeutic efficacy was evaluated 2 months after gene delivery.

RESULTS

Transduction efficacy after intratracheal delivery of AAV1 was confirmed by β-galactosidase detection in the distal pulmonary vasculature. Treatment with aerosolized AAV1.SERCA2a prevented disease progression as evaluated by mean pulmonary artery pressure, vascular resistance, and limited vascular remodeling quantified by histology. Therapeutic efficacy was supported further by the preservation of RV ejection fraction (p = 0.014) and improvement of the RV end-diastolic pressure–volume relationship in PH pigs treated with aerosolized AAV1.SERCA2a.

CONCLUSIONS

Airway-based delivery of AAV vectors to the pulmonary arteries was feasible, efficient, and safe in a clinically relevant chronic PH model. Vascular SERCA2a overexpression resulted in beneficial effects on pulmonary arterial remodeling, with attendant improvements in pulmonary hemodynamics and RV performance, and might offer therapeutic benefit by modifying fundamental pathophysiology in pulmonary vascular diseases. (J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2032–46).

Keywords: aerosol delivery, gene therapy, pig models, pulmonary vascular remodeling, right ventricular function

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a group of pulmonary endovascular diseases with hemodynamic consequences for right ventricular (RV) function that portends a poor clinical prognosis. Although the current classification system for PH segregates patients on the basis of clinical and pathological features, all forms of PH are associated with some degree of aberrant pulmonary vascular remodeling (1). Current pharmacotherapies for PH do not target pulmonary vascular remodeling directly but rather aim to promote pulmonary artery vasodilation and reduce RV afterload as adverse outcomes are driven mainly by the onset of RV failure (2,3).

Epidemiological studies indicate that PH associated with increased pulmonary venous pressure and left heart failure (HF) is the most common cause of chronic PH (4). Furthermore, more than one-half of all patients with HF may develop chronic PH, leading to even more adverse cardiac events (5). Similar to pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) (Group 1 PH), left heart disease–related PH (Group 2 PH) has been associated with impaired pulmonary vascular reactivity, endothelial dysfunction, and excessive arteriolar muscularization, indicating that pre-capillary pulmonary vascular remodeling is present concomitant with post-capillary disease (6). Despite this, therapeutics that are effective in PAH are either not effective, have not been tested, or may be contraindicated in patients with left HF and PH (1).

Currently available pharmacotherapies were developed to ameliorate disease symptomatology by targeting 1 of 3 main signaling pathways found to be deficient or activated in PH (7). Although several available compounds have shown benefit in Group 1 PH in randomized clinical trials, unresolved issues remain. These include: 1) few studies in patients with Group 2 PH; 2) a lack of evidence of long-term clinical efficacy; 3) uncertainty regarding the effects of drugs on limiting or reversing vascular remodeling in the presence of established disease; 4) the risk of serious adverse effects that limit dose escalation within or between class combination therapy; and 5) the high cost of long-term treatments. Thus, novel approaches are needed.

Gene therapy has evolved over the past several decades due to advances in vector technology and delivery methodologies. In a wide range of chronic disorders, including cardiovascular disease (8,9), efficient gene transfer has been achieved by newly designed recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. Several experimental studies have reported successful modulation of PH signaling pathways in a specific and efficient manner using gene therapy (10). Proof-of-concept studies in rodent PH models have demonstrated the feasibility of gene transfer of molecules related to currently available pharmacotherapies, such as the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (11) or prostacyclin synthase (12), that hold promise for treating PH in humans.

Abnormal calcium homeostasis in smooth muscle cells (SMCs) contributes to PH pathobiology (13). Chronically increased intracellular calcium levels in pulmonary artery SMCs trigger signaling pathways that are permissive for cellular proliferation, migration, and dedifferentiation, all of which contribute to hypertrophic vascular remodeling (13). Our group has reported previously that sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase pump 2a (SERCA2a) is a key modulator of calcium cycling in both cardiomyocytes and vascular SMCs (14). We recently demonstrated that pulmonary arterial SERCA2a expression is down-regulated in the rat monocrotaline model of PH as well as in humans with PAH. Furthermore, we demonstrated in the rat model that selective pulmonary vascular gene transfer of SERCA2a using AAV1 was feasible, ameliorated arterial remodeling, and improved hemodynamic abnormalities and RV function (15).

Despite the evidence that gene therapy targeting SERCA2a has merit, a major hurdle in the translation of novel therapeutics to the clinic is the limited availability of large animal models of PH that recapitulate human disease. Most pre-clinical drug development studies evaluate interventions in rodent models of PH (16), yet there are marked differences between rodent models and human anatomy and physiology (17). Accessible large animal models of chronic PH allow for a more relevant approach to evaluate novel interventions prior to human clinical trials, as they offer similar dosing therapeutic schemes, human-sized delivery tools, and state-of-the-art diagnostic protocols to assess critical endpoints such as pulmonary hemodynamics and RV structure and function (18,19). Validating the results of rodent studies in large animal models of chronic PH therefore increases the likelihood of success in drug development at the pre-clinical stage (17).

The objectives of this study were to assess the feasibility of sustained pulmonary vascular SERCA2a gene transfer in a large animal model of chronic post-capillary PH and to evaluate the efficacy of gene transfer on the progression of pulmonary vascular and RV remodeling. On the basis of the encouraging results in a number of studies (12,20,21), including our own proof-of-concept study in a rodent model of PH (15), we tested a novel aerosol inhalation gene delivery strategy to minimize off-target transgene expression and increase safety.

METHODS

The study was performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, with approval granted by the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Results are reported following the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines. Detailed methodology is available in the Online Appendix.

STUDY DESIGN

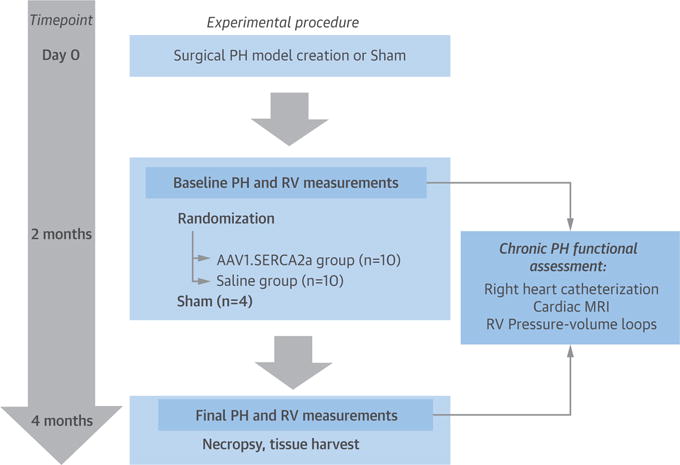

The study was designed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of SERCA2a gene transfer to the pulmonary vasculature using a novel aerosolized inhalation gene delivery strategy in a large animal model of chronic PH. Specifically, a swine model of chronic post-capillary PH was created surgically by partial banding of the pulmonary venous drainage, as reported previously by our group (18). The model produced a predictable and sustained rise in pulmonary artery (PA) pressures and RV dysfunction. Two months after the banding procedure, animals with established PH were randomized to airway-based AAV1.SERCA2a gene transfer (n = 10) or saline administration (n = 10) and followed for an additional 2 months until the end of the study. A sham-operated group (n = 4) was included as a control for the PH model. The main efficacy endpoints for the study were invasive cardiopulmonary hemodynamic parameters and RV performance indexes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Study Design and Timeline.

The chronic pulmonary hypertension (PH) model was created surgically by selective banding of pulmonary veins in 10- to 15-kg piglets. Two months later, animals were randomized to aerosolized airway delivery of either recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 1 carrying the human SERCA2a transgene (AAV1.SERCA2a) or saline. Changes in cardiopulmonary hemodynamics, right ventricular (RV) structure, and RV function were evaluated 2 months after randomization to treatment. Sham-operated animals (n = 4) served as controls. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

Human recombinant AAV1.SERCA2a and AAV1.LacZ for transduction efficiency studies were produced as described previously (22). The high prevalence of preexisting or post-exposure neutralizing antibodies is a major hurdle for AAV-based gene therapies in both animal (23) and human studies (24). We therefore quantified neutralizing antibody titers against the AAV1 serotype before and after airway delivery of the AAV1 vector using a standardized protocol available in our laboratory (25).

Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane 1% to 2%. AAV1.SERCA2a (1 × 1013 vg) or saline aerosol delivery was performed using the MicroSprayer Aerosolizer (Model IA-1B, Penn-Century, Inc., Wyndmoor, Pennsylvania). This aerosolizer produces particles of ~20 μm; airway delivery of AAVs using this system has been shown to be effective in other large animal models (26). Using fluoroscopic guidance, the aerosol needle was inserted in the airway through the endotracheal tube using a 7-F multipurpose coronary diagnostic catheter with the tip of the catheter positioned near the carina (Online Figures 1A and 1B). The total dose of AAV1.SERCA2a was diluted into 6 ml of sterile saline and aerosolized in 2 ml doses with the animal in the dorsal, right, and left lateral recumbent positions. After virus delivery was completed, the animal was mechanically ventilated for an additional 20 to 30 min with continuous monitoring of the electrocardiogram, hemodynamics, and respiratory parameters. After this time, the animal was recovered fully from the procedure.

Before randomization to the treatment groups, all animals underwent right heart catheterization to measure cardiopulmonary pressures for RV pressure-volume analysis.

At 2 months (baseline) and 4 months (final), cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging studies were performed with a 3.0-T magnet to examine changes in RV and left ventricular (LV) structure and function.

HISTOLOGY

After the animals were euthanized, the RV and LV were sectioned and weighed, and RV hypertrophy was assessed by the following ratio: RV/(LV + septum). Heart and lung tissue samples were placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution and were subsequently fixed, processed, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned into 5-μm–thick sections for histology and morphometry analyses.

Protein quantification of SERCA2a was performed in lung and RV tissue homogenates and standardized using β-actin as described previously (15). Immunostaining was performed on acetone-fixed lung sections as reported previously (15), using primary antibodies as described in the Online Appendix.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables are expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR) unless otherwise specified. The invasive cardiopulmonary hemodynamic parameters and invasive RV performance indexes are reported as the mean change estimate with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each group. The study groups were compared at the time of randomization (baseline) using 1-way analysis of variance (with post hoc comparisons between groups performed using the Holm-Bonferroni method or Dunnett’s multiple comparisons method), and change over time was evaluated by the group × time interaction of the repeated measures analysis of variance model. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

RESULTS

Two months after the model was created, PH was confirmed hemodynamically by invasive right heart catheterization prior to the delivery of aerosolized AAV1.SERCA2a or saline; this time point was considered the baseline for future studies that evaluated the effectiveness of gene transfer. After an additional 2 months following aerosol inhalation delivery of the randomized treatment, a final assessment of cardiopulmonary hemodynamics, vascular remodeling, and RV structure and function was performed (Figure 1).

In a pre-dosing study that established the time course of hemodynamic compromise in the swine chronic PH model, we found that the onset of RV failure was associated with rapid disease progression and early death. Thus, to ensure that we would have sufficient power to examine the effects of AAV1.SERCA2a gene transfer on pulmonary vascular and RV endpoints, we excluded from randomization those animals found to have a mean PA pressure >45 mm Hg or a low cardiac index (<2.5 l/m2) at right heart catheterization, as these measures were associated with RV failure and early death (Online Table 1). At baseline (once the PH was confirmed), compared with sham control subjects (n = 4), we documented a significant increase in mean PA pressure in PH pigs randomized to saline (n = 10) and AAV1.SERCA2a (n = 10) (median 17 mm Hg [IQR: 15 to 18 mm Hg] vs. 26 mm Hg [IQR: 23 to 30 mm Hg] vs. 23 mm Hg [19 to 28 mm Hg], respectively; p = 0.004). There were no significant between-group differences with respect to body weight, pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP), mean aortic pressure, or heart rate. Cardiac index was increased in PH pigs compared with sham control subjects (p = 0.004), which is a recognized feature of this model that has been described previously (18,27) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cardiopulmonary Hemodynamics*

| Sham | Saline | AAV1.SERCA2a | p Value (ANOVA) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 4) | Final (n = 4) | Baseline (n = 10) | Final (n = 8) | Baseline (n = 10) | Final (n = 8) | Baseline (Between Groups) | Group/Time Interaction | |

| Body weight, kg | 21.5 (21–22.8) | 34 (31.5–36.3) | 20.5 (19–23) | 30.5 (28.5–32.5) | 22.5 (20.5–24.8) | 36 (34–37.3) | 0.547 | 0.237 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 61 (55–66) | 75 (74–76) | 73 (71–84) | 73 (64–99) | 68 (57–82) | 78 (71–86) | 0.071 | 0.684 |

| Mean aortic pressure, mm Hg | 92 (89–99) | 121 (116–125) | 85 (80–93) | 103 (90–127) | 84 (81–90) | 112 (104–127) | 0.242 | 0.695 |

| Systolic PA pressure, mm Hg | 22 (21–22) | 23 (22–24) | 34 (30–44) | 70 (59–87) | 34 (28–38) | 40 (33–44) | <0.001† | 0.003†§ |

| Diastolic PA pressure, mm Hg | 10 (9–10) | 10 (9–10) | 15 (12–20) | 35 (29–46) | 14 (11–17) | 18 (15–20) | 0.014 | 0.004†§ |

| Mean PA pressure, mm Hg | 17 (15–18) | 16 (15–17) | 26 (23–30) | 54 (43–63) | 23 (19–28) | 29 (26–31) | 0.004†‡ | 0.003†§ |

| PA wedge pressure, mm Hg | 10 (8–10) | 9 (7–9) | 12 (10–14) | 15 (11–18) | 9 (5–11) | 12 (10–14) | 0.244 | 0.482 |

| Diastolic pulmonary gradient, mm Hg | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 5 ([–1]–8) | 22 (10–26) | 4 (2–6) | 6 (1–9) | 0.281 | 0.01†§ |

| RA pressure, mm Hg | 4 (3–5) | 2 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | 4 (3–5) | 4 (3–5) | 2 (1–3) | 0.044§ | 0.001†§ |

| Cardiac index, l/min/m2 | 3.38 (3.29–3.51) | 4.52 (4.3–4.86) | 4.33 (4.13–5.13) | 3.70 (3.14–4.68) | 4.06 (3.53–5.04) | 5.43 (4.71–5.76) | 0.004† | 0.052 |

| Stroke volume index, ml/m2 | 58 (54–61) | 60 (57–65) | 57 (51–70) | 51 (43–74) | 59 (50–71) | 65 (59–78) | 0.870 | 0.269 |

| PVR index, WU/m2 | 1.93 (1.29–3.03) | 1.56 (1.49–1.85) | 2.83 (2.55–4.38) | 10.3 (5.14–12.21) | 3.17 (2.3–4.8) | 3.17 (1.8–4) | 0.459 | 0.002†§ |

| SVR index, WU/m2 | 26 (24.6–28.7) | 27 (25.3–27.1) | 17.5 (17–22.4) | 27.4 (21.2–31.7) | 19.4 (18–22) | 21.9 (20.5–24.5) | 0.052 | 0.055 |

Values are median (interquartile range [IQR]).

Baseline was at 2 months after model creation and final was at 4 months after model creation (and 2 months after gene transfer).

Pairwise post hoc p < 0.05 sham versus saline.

Pairwise post hoc p < 0.05 for sham versus AAV1.SERCA2a.

Pairwise post hoc p < 0.05 for saline versus AAV1.SERCA2a.

AAV1.SERCA2a = recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 1 carrying the human SERCA2a transgene; ANOVA = analysis of variance; PA = pulmonary artery; PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance; RA = right atrium; SVR = systemic vascular resistance; WU = Wood units.

After randomization, 3 animals died during the 2-month treatment follow-up period (2 in the saline group and 1 in the AAV1.SERCA2a group). In all 3 deaths, there were no complications that occurred during or after the airway inhalation gene therapy delivery procedure. The deaths occurred more than 1 month after randomization and were not attributable to the intervention. At necropsy, there was no evidence of lung infiltrates or infection; however, all 3 animals had evidence of severe right HF, including hepatomegaly and ascites, implicating this as the primary cause of death. From these nonsurvivors, the only available outcome measurement was RV weight obtained at the time of heart explantation and is reported in Online Table 1. One animal (AAV1.SERCA2a group) that survived to the final time point had clear evidence of pneumonia with respiratory insufficiency and failure to thrive; this animal was excluded from the analyses (Online Table 1). Of the remaining animals that completed the study, no signs of pulmonary infection or congestion were identified at necropsy. In all cases, aerosol inhalation delivery of either AAV1.SERCA2a or saline was well tolerated and did not result in respiratory or hemodynamic instability.

SERCA2a GENE TRANSFER AND CARDIOPULMONARY HEMODYNAMICS

First, transduction efficiency of the AAV1 vector was examined using airway delivery of AAV1.LacZ. Examination of lung tissue sections stained for β-galactosidase demonstrated abundant transduction of the distal pulmonary airways and vessels (Online Figure 2). Further evaluation of the main PAs and vessels in the RV and LV revealed that these vessels were not transduced, indicating that aerosolized inhalation of AAV1.SERCA2a delivered the transgene to the target vasculature effectively and that there was no unanticipated gene transfer to cardiac vessels or other nontarget organs (Online Figures 3 and 4). Thus, the observed cardiopulmonary hemodynamic effects of treatment with aerosolized AAV1.SERCA2a are due to transduction of the distal pulmonary vessels and effects on pulmonary vascular remodeling as opposed to targeting the RV.

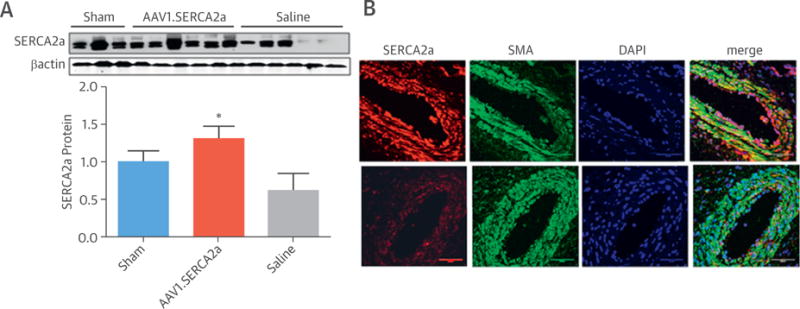

FIGURE 4. Lung and Pulmonary Artery SERCA2a Protein Expression.

(A) Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) protein expression was quantified in lung homogenates by Western blotting. Representative blots are shown with densitometry data provided below comparing sham (n = 3), adeno-associated virus serotype 1 carrying the human SERCA2a transgene (AAV1.SERCA2a)-treated (n = 6), and saline-treated (n = 6) animals. *p < 0.05 vs. saline. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images from confocal microscopy showing specific localization of SERCA2a protein (red) in pulmonary vessels and distal airway epithelium in AAV1.SERCA-treated (top) and saline-treated (bottom) animals. Green and blue staining localize to α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), respectively. Bar = 50 μm.

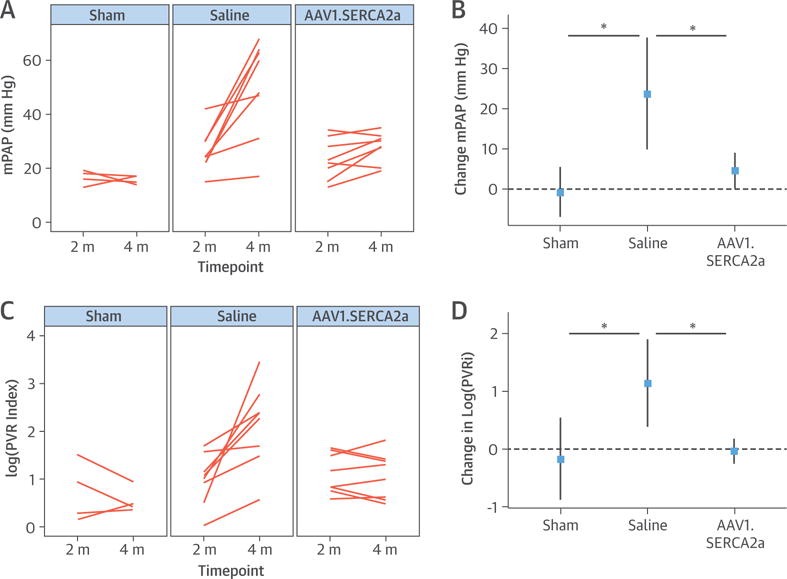

At the end of the study, 8 animals from the AAV1.SERCA2a-treated group and 8 animals from the saline-treated group were available for analysis. Although mean PA pressures in the sham control subjects did not change during the study, the increase in mean PA pressure was significantly larger in PH pigs randomized to saline compared with AAV1.SERCA2a (median 54 mm Hg [IQR: 43 to 63 mm Hg] vs. 29 mm Hg [IQR: 26 to 31 mm Hg]; p < 0.05) (Figures 2A and 2B). Compared with baseline, mean PA pressure continued to increase in PH pigs randomized to saline (median 26 mm Hg [IQR: 23 to 30 mm Hg] vs. 54 mm Hg [IQR: 43 to 63 mm Hg]; paired Student t test p = 0.005); however, compared with baseline, disease progression was limited in the AAV1.SERCA2a PH pigs (median 23 mm Hg [IQR: 19 to 28 mm Hg] vs. 29 mm Hg [IQR: 26 to 31 mm Hg]; paired Student t test p = 0.064) (Table 1, Figures 2A and 2B). Corresponding to the observed changes in PA pressure, indexed pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) was increased significantly in the saline-treated group but not in animals receiving AAV1.SERCA2a (median 10.3 Wood U/m2 [IQR: 5.1 to 12.2 Wood U/m2] vs. 3.17 Wood U/m2 [IQR: 1.8 to 4.0 Wood U/m2]; p < 0.05) (Figures 2C and 2D), suggesting that treatment with AAV1.SERCA2a had a beneficial effect on pulmonary vascular remodeling. There was a parallel increase in the diastolic pulmonary gradient in the saline group (median 5 mm Hg [IQR: −1 to 8 mm Hg] to 22 mm Hg [IQR: 10 to 26 mm Hg]; p < 0.05) that was not present in AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals (median 4 mm Hg [2 to 6 mm Hg] vs. 6 mm Hg [1 to 9 mm Hg]; p = NS). We also found that the cardiac index, which was increased at baseline in PH pigs, was decreased in the saline group by the end of the study, but improved in animals treated with AAV1.SERCA2a, although there was no significant difference between these groups (p = 0.112) (Table 1).

FIGURE 2. Pulmonary Hemodynamics.

Individual changes from baseline (2 months [m]) to study’s end (4 months) are reported for each animal following right heart catheterization to evaluate the effect of adeno-associated virus serotype 1 carrying the human SERCA2a transgene (AAV1.SERCA2a) therapy on cardiopulmonary hemodynamics. (A) The mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) and (C) pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRi) reported as well as the corresponding mean changes for each study parameter (B and D) demonstrate improvement with AAV1.SERCA2a. Sham (n = 4), saline (n = 8), AAV1.SERCA2a (n = 8). *p < 0.05. PVR = pulmonary vascular resistance.

To confirm that the observed effects of AAV1.SERCA2a on cardiopulmonary hemodynamics were attributable to gene transfer to the pulmonary vasculature and not an effect of the degree of partial venous banding, we also examined the degree of constriction imposed by the banding procedure over time using Doppler echocardiography (Online Figure 5). Compared with sham control subjects, Doppler velocities in the pulmonary veins in animals with PH at the time of randomization to treatment with AAV1.SERCA2a or saline were increased 3- to 4-fold with no between-group differences. Two months after administration of AAV1.SERCA2a or saline, Doppler velocities remained elevated, with no difference observed between the groups or compared with baseline. Thus, the effect of AAV1.SERCA2a on cardiopulmonary hemodynamics resulted from transduction of the pulmonary vessels (Online Table 2).

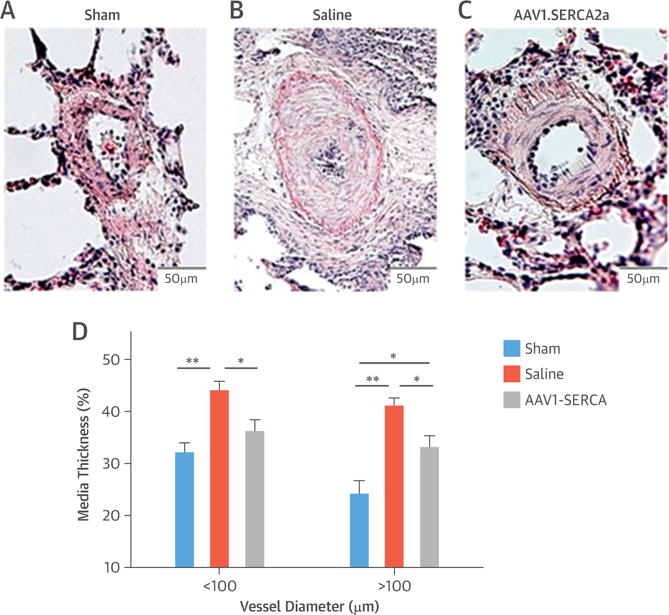

SERCA2a GENE TRANSFER AND HYPERTROPHIC PA REMODELING

Increased medial thickness and hypertrophic PA remodeling are the main indexes of vascular remodeling observed in this porcine model of chronic PH (18,27). In the present study, compared with sham control subjects, PH pigs randomized to saline had significantly increased medial thickness of vessels <100 μm (p < 0.01) and vessels >100 μm (p < 0.01). Although there was some evidence of pulmonary arteriole remodeling in PH pigs treated with AAV1.SERCA2a, there was significantly less medial thickness of vessels <100 μm (p < 0.05) and >100 μm (p < 0.05) compared with that observed in saline-treated PH pigs (Figure 3). These findings agreed with the hemodynamic data described earlier.

FIGURE 3. Pulmonary Vascular Remodeling.

Distal vascular remodeling is ameliorated in adeno-associated virus serotype 1 carrying the human SERCA2a transgene (AAV1.SERCA2a)–treated animals compared with the saline group. Representative hematoxylin-eosin staining is shown for (A) sham (n = 4), (B) saline-treated (n = 8), and (C) AAV1.SERCA2a-treated (n = 8) animals. (D) Medial thickness was quantified for pulmonary arteries of <100 and >100 μm diameter. Data are mean SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Next, to determine if the observed findings in the pulmonary vessels could be attributed to SERCA2a gene transfer, we analyzed the association of vascular remodeling with SERCA2a protein expression. Consistent with our observations in patients with PAH (15), SERCA2a protein was decreased in lung homogenates in the saline group compared with sham subjects; however, significantly higher SERCA2a levels were detected in the AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals (Figure 4A). Immunofluorescence imaging of pulmonary vessels with dual labeling of SERCA2a and α-smooth muscle actin or SERCA2a and eNOS revealed that SERCA2a was detected primarily in the medial layers of the distal pulmonary arteries with some expression in the endothelium as well as the distal airway epithelium (Figure 4B, Online Figure 6). The abundance of SERCA2a detected in vessels of animals treated with AAV1.SERCA2a was greater than that observed in the saline-treated group (Figure 4B).

In a prior study performed in a rodent model of PH, we found that SERCA2a expression was inversely related to STAT3, which has been shown to regulate PA remodeling. To determine if this mechanism was operative in our porcine model, we first examined STAT3 phosphorylation in lung tissue homogenates. Compared with saline-treated PH pigs, animals treated with AAV1.SERCA2a had a lower level of STAT3 phosphorylation (p < 0.01) (Online Figure 7). As STAT3 has been identified as a mechanism that regulates bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (BMPR2) expression, we next examined this relationship in PA SMCs infected with an adenovirus encoding SERCA2a. Compared with cells infected with an adenovirus encoding β-galactosidase as a control, SERCA2a-infected cells had decreased STAT3 phosphorylation (p < 0.005) and a trend toward increased expression of BMPR2 (p = 0.07), suggesting that this may be a mechanism by which SERCA2a gene transfer improves pulmonary vascular remodeling (Online Figure 8).

EFFECT ON RV STRUCTURE AND PERFORMANCE

To evaluate the effect of pulmonary vascular gene transfer of SERCA2a on changes in RV remodeling and global function, serial CMRs were performed before randomization and at the final time point. Animals subsequently randomized to saline or AAV1.SERCA2a were found to have similar RV volume, RV ejection fraction (EF), and indexed RV mass at baseline. Similarly, there were no between-group differences with respect to LV volume or LVEF (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

CMR Analysis of Ventricular Structure and Function*

| Saline | AAV1.SERCA2a | p Value† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 9) | Final (n = 5) | Baseline (n = 10) | Final (n = 8) | Baseline | Group/Time Interaction | |

| rRV EDV, ml/m2 | 108 (99–129) | 161 (110–165) | 111 (104–138) | 132 (124–156) | 0.710 | 0.878 |

| RV ESV, ml/m2 | 45 (40–57) | 82 (54–91) | 48 (41–55) | 51 (45–66) | 0.971 | 0.101 |

| RVEF, % | 58 (56–64) | 50 (44–51) | 59 (58–63) | 61 (56–63) | 0.754 | 0.008 |

| RV mass, g/m2 | 56 (49–69) | 62 (57–63) | 64 (55–71) | 59 (55–62) | 0.489 | 0.014 |

| Stroke volume, ml/m2 | 58 (55–64) | 55 (37–64) | 69 (52–71) | 71 (57–81) | 0.200 | 0.084 |

| LV EDV, ml/m2 | 87 (78–93) | 89 (66–108) | 97 (92–105) | 109 (105–112) | 0.090 | 0.022 |

| LV ESV, ml/m2 | 31 (29–33) | 33 (28–42) | 38 (35–40) | 38 (33–43) | 0.157 | 0.571 |

| LVEF, % | 64 (63–67) | 61 (61–62) | 62 (58–63) | 65 (63–66) | 0.620 | 0.085 |

Values are median (IQR).

Baseline was at 2 months after model creation and final was at 4 months after model creation (and 2 months after gene transfer).

Independent samples Student t test.

CMR = cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; RV = right ventricular; EDV = end-diastolic volume; EF = ejection fraction; ESV = end-systolic volume; LV = left ventricular; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

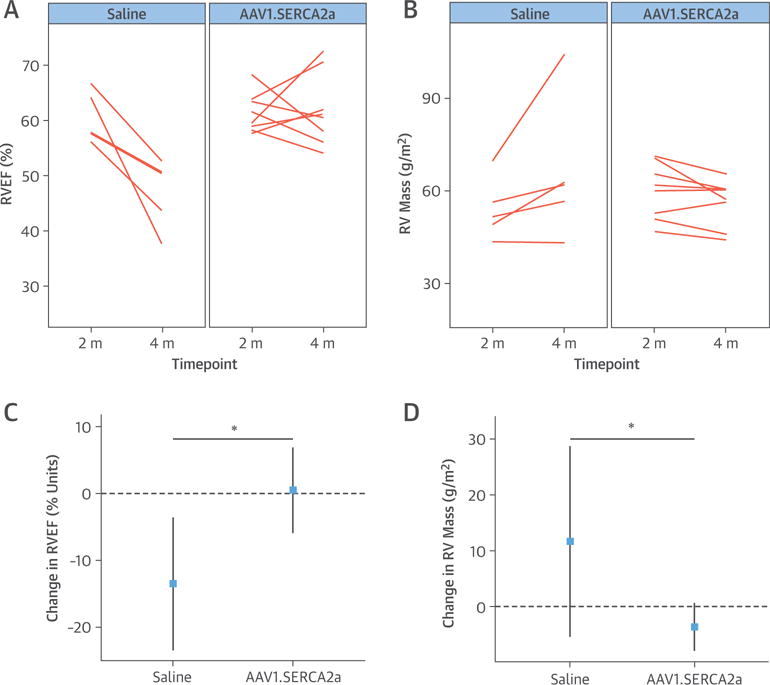

In the saline group, RV function worsened by the study’s end, with a decrease in RVEF that was associated with an increase in RV end-diastolic and end-systolic volume indexes as well as an increase in RV mass (paired Student t test p = 0.130) (Table 2, Figures 5A and 5B). In PH pigs randomized to AAV1.SERCA2a, however, RVEF remained relatively stable over the 2-month follow-up period post-gene transfer. Indeed, compared with saline-treated animals, the change in RVEF in AAV1.SERCA2a-treated PH pigs was significantly less (p = 0.008), and there was a decrease in RV mass (p = 0.014) (Figures 5C and 5D). At the end of the study, explanted hearts were weighed as a more solid measure of RV mass. There was a significant increase in RV/LV + septum in the saline group compared with sham control subjects (p = 0.006), with a nonsignificant decrease in relative RV weight in AAV1.SERCA2a animals.

FIGURE 5. RV Remodeling.

Serial cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) was performed to examine the effect of aerosolized adeno-associated virus carrying SERCA2a (AAV1.SERCA2a) on RV structural remodeling. At the end of the 2-month treatment period, CMR-derived measures of (A) right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) and (B) indexed RV mass were preserved in the AAV1.SERCA2a-treated pigs (n = 8) but decreased in saline-treated pigs (n = 5). Mean change estimates with 95% confidence intervals are shown for (C) RVEF and (D) RV mass. *p < 0.05. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

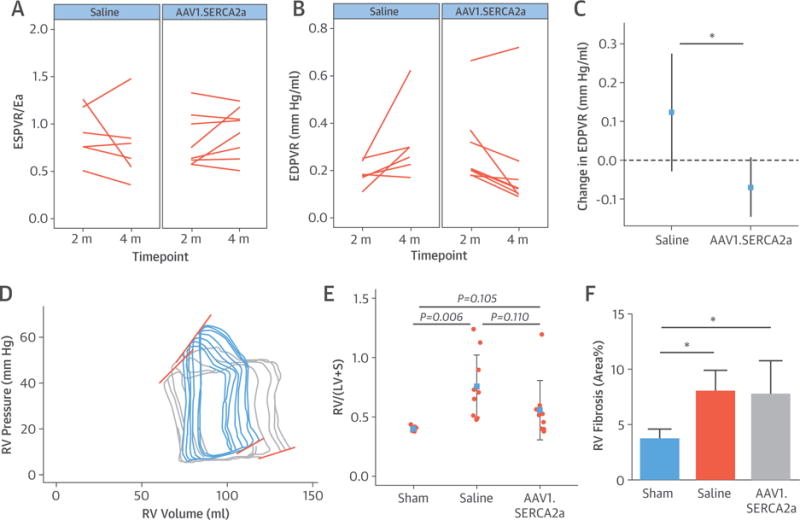

To assess RV function further at the end of the treatment period, RV pressure-volume relationships were examined (Figure 6). At baseline, all measures were similar between animals randomized to saline and AAV1.SERCA2a (Table 3). At the end of the study, RV end-systolic pressure-volume relationship or elastance, a measure of RV contractility, was improved in AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals compared with the saline group (p = 0.043). The change in arterial elastance (Ea), or RV afterload, was significantly higher in saline-treated animals compared with AAV1.SERCA2a-treated pigs (p = 0.005). Moreover, the increase in pulmonary Ea was not compensated by an increase in end-systolic pressure-volume relationship in the saline group, whereas an improved Ea was observed in the AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals, suggesting better RV-PA coupling. Among diastolic parameters, a marked improvement in end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (i.e., RV compliance) was observed in the AAV1.SERCA2a group compared with the saline group (p = 0.006) (Table 3, Figure 6). In both PH groups, a significant degree of pathological fibrosis was found in the RV myocardium compared with the sham control subjects, with no quantitative differences detected between the treatment groups. Compared with control subjects, SERCA2a expression in the RV was decreased in saline-treated and AAV1.SERCA2a-treated (both p < 0.05) PH animals with no between-group difference in SERCA2a expression (Online Figure 9). This suggests that any observed improvements in RV function in AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals are more likely to be attributed to reduced afterload than a higher RV SERCA2a expression.

FIGURE 6. Indexes of RV Performance.

At randomization and after the 2-month treatment period, RV pressure–volume relationships were assessed invasively and reported for animals randomized to saline (n = 6) or AAV1.SERCA2a (n = 8). End-systolic pressure–volume relationship (ESPVR) (A) and end-diastolic pressure–volume relationship (EDPVR) (B) slopes are shown, together with mean change estimate for EDPVR (C). (D) Representative pressure-volume loop volume reduction series from saline-treated (blue) and AAV1.SERCA2a-treated (gray) animals show steeper slopes for the saline group. (E) Relative RV weight from explanted hearts expressed as RV/left ventricle + septum (LV+S). (F) Myocardial interstitial fibrosis was assessed as collagen fractional area, which was quantified in RV free wall tissue by picrosirius red staining. *p < 0.05. Ea = arterial elastance; other abbreviations as Figure 1.

TABLE 3.

RV Invasive Pressure-Volume Loop Measurements*

| Saline | AAV1.SERCA2a | p Value† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 10) | Final (n = 6) | Baseline (n = 10) | Final (n = 8) | Baseline | Group/Time Interaction | |

| PA Ea, mm Hg/ml | 1.25 (0.96 to 1.54) | 1.88 (1.09 to 2.09) | 1.02 (0.81 to 1.32) | 0.81 (0.61 to 0.96) | 0.653 | 0.005 |

| ESPVR slope, mm Hg/ml | 1.13 (0.64 to 1.40) | 0.92 (0.74 to 1.40) | 0.77 (0.63 to 1.15) | 0.63 (0.53 to 0.76) | 0.216 | 0.043 |

| Vo, ml | −4.9 (−18.3 to 2.1) | −14 (−30.3 to 5.2) | −10.5 (−18.2 to 2.3) | −24.8 (−37.1 to 3.8) | 0.856 | 0.6 |

| ESPVR/Ea | 0.84 (0.69 to 1.18) | 0.72 (0.57 to 0.84) | 0.74 (0.62 to 0.97) | 0.97 (0.72 to 1.08) | 0.434 | 0.167 |

| dP/dt max, mm Hg/s | 624 (591 to 800) | 764 (690 to 875) | 662 (493 to 731) | 690 (671 to 861) | 0.551 | 0.84 |

| EDPVR slope, mm Hg/ml | 0.21 (0.17 to 0.32) | 0.28 (0.23 to 0.30) | 0.27 (0.20 to 0.37) | 0.12 (0.10 to 0.18) | 0.391 | 0.006 |

| dP/dt min, mm Hg/s | −623 (−732 to −468) | −907 (−1,039 to −629) | −486 (−628 to −406) | −560 (−626 to −474) | 0.372 | 0.097 |

| Tau, ms | 33 (26 to 41) | 37 (34 to 40) | 33 (31 to 37) | 34 (32 to 36) | 0.301 | 0.423 |

Values are median (IQR).

Baseline was at 2 months after model creation and final was at 4 months after model creation (and 2 months after gene transfer).

Independent samples Student t test.

dP/dt = peak RV pressure rate of rise (max) or decline (min); Ea = arterial elastance; EDPVR = end-diastolic pressure–volume relationship; ESPVR = end-systolic pressure–volume relationship; PA = pulmonary artery; Tau = time constant of isovolumic relaxation; Vo = volume intercept of the ESPVR slope; other abbreviations as in Tables 1 and 2.

ALDOSTERONE LEVELS AND NEUTRALIZING ANTIBODIES

Aldosterone levels were measured at study’s end as an additional indication of right HF status. Aldosterone levels were elevated in saline-treated pigs compared with control subjects, with lower levels detected in AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals (mean ± SD: 30.6 ± 5.2 vs. 76.6 ± 7.3 vs. 51.4 ± 7.1 mg/dl; p < 0.02). In almost all animals receiving airway delivery of aerosolized AAV1.SERCA2a or AAV1.LacZ vectors, neutralizing antibody titers increased by the end of the study, whereas no change in titers was found in animals from the saline group that were not exposed to any AAV1 viral vectors (Online Figure 10).

DISCUSSION

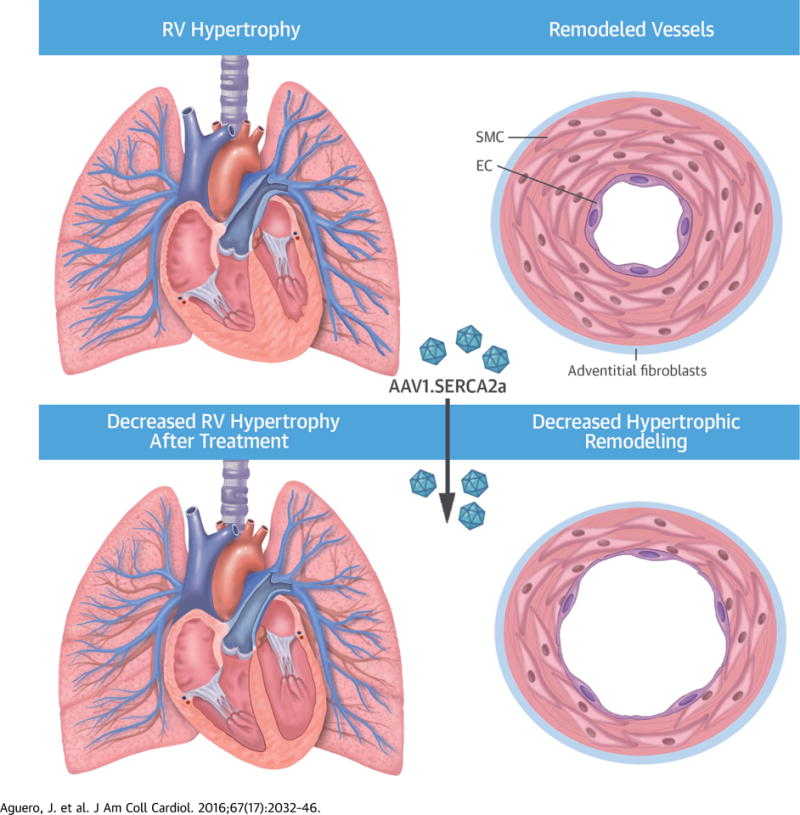

In this study, we report for the first time a successful AAV-based gene therapy intervention that modulated progression of chronic PH in a large animal model. We provide data that support feasibility, efficiency, and safety of airway distribution and transduction of small pulmonary vessels using an aerosolized AAV1 vector as a novel delivery method for gene therapy in PH. We also describe the beneficial effects of selective vascular SERCA2a gene transfer using this approach. In this study, PA transduction with aerosolized AAV1.SERCA2a improved cardiopulmonary hemodynamics and RV functional parameters in a chronic PH model that recapitulates the clinical features of the disease seen in patients with chronic post-capillary PH (Central Illustration). These data indicate that AAV1.SERCA2a therapy slowed the progression of PH in a clinically relevant large animal model and confirm the potential therapeutic role of SERCA2a as a novel target in PH patients. Our data also extends the “proof-of-concept” strategy of aerosolized gene transfer of SERCA2a (15) by demonstrating efficacy in a truly pre-clinical animal model of PH. As there are no established therapies that target prevention of pulmonary vascular remodeling, a fundamental pathophysiology of PH, our findings offer an innovative option to treat patients with PH.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Inhaled AAV1.SERCA2a in PH.

Chronic pulmonary hypertension (PH) is associated with increased right ventricular (RV) afterload and vascular remodeling, leading to right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) that results from distal pulmonary artery hypertrophic remodeling. Airway gene delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 1 carrying the human SERCA2a transgene (AAV1.SERCA2a) limits RV hypertrophy and failure by attenuating the progression of pulmonary artery hypertrophic remodeling in a swine model. EC = endothelial cell; SMC = smooth muscle cell.

The time course of PH and pulmonary arteriolar remodeling in the swine model of chronic PH has been established. In this model, increases in PA pressure occur prior to a rise in pulmonary vascular resistance. This, in turn, precedes RV remodeling, dysfunction, and, ultimately, failure (19). In the current study, we found that the progression of disease through these stages was ameliorated by intratracheal administration of aerosolized AAV1.SERCA2a. This was demonstrated by stabilization of the mean PA pressure and PVR at the end of the 2-month follow-up period. These observations also agreed with pulmonary vascular remodeling assessed by medial thickness scores of small (<100 μm) and medium (>100 μm) vessels. We further confirmed that SERCA2a was down-regulated in the PAs in the swine model of chronic PH compared with sham control subjects, similar to what was observed in human PAH pulmonary arterioles and in the rat monocrotaline-induced PH model (15). Of note, pulmonary vascular SERCA2a abundance was markedly higher in AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals compared with the saline group, indicating that there was efficient vessel transduction and that restoring PA SERCA2a levels prevented disease progression.

These observations support previous reports from our group regarding the association of SERCA2a down-regulation with adverse vascular remodeling in both the pulmonary (15) and coronary circulations (28). In the hypertensive pulmonary vasculature, gene transfer of SERCA2a exerted antiproliferative effects by blocking the STAT3-NFAT pathway in SMCs (15). Additionally, in vitro studies revealed that SERCA2a overexpression restored eNOS to basal levels (15). These mechanistic studies provide the molecular basis for the observed beneficial effects of SERCA2a in pulmonary vascular remodeling in the present model.

RV failure is the main determinant of clinical outcome in patients with PH (29). In our chronic PH model treated with AAV1.SERCA2a, hemodynamic improvements were paralleled by the preservation of RV performance as evaluated by systolic, diastolic, and remodeling parameters quantified by serial CMR and pressure-volume relationships. In a previous report, we comprehensively analyzed the onset of RV failure in this model of chronic PH and found that the progression of vascular disease was responsible for nonadaptive RV remodeling and uncoupling from the pulmonary circulation leading to RV failure (18). In the present study, the most relevant differences between treatment groups were found in diastolic function as assessed by end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship. The fact that beneficial effects observed in RV performance were not paralleled by differences in interstitial fibrosis between treatment groups suggests that RV performance improvement likely reflected hemodynamic changes and could not be attributed to the prevention or reversal of RV fibrosis. Interestingly, reports using CMR have shown that RV failure may occur even in the presence of a favorable hemodynamic response to vasodilator drugs in PAH patients (3). This also underscores the need for a better understanding of the intrinsic mechanisms of RV structural and functional remodeling to affect the clinical outcome of this patient population (3).

In the past 2 decades, several groups have explored gene therapy as a strategy to improve or correct PH in rodent models (10), under the premise that specific vascular targeting of therapeutics would increase efficacy and decrease systemic side effects. Successful experiences have been reported in the selective modulation of eNOS (30) and prostacyclin synthase (12,31,32), aiming to enhance sustained availability of short-lived endothelial factors, such as NO or prostacyclin, which are known to be deficient in PH. Other targets of interest that have been studied in small animal models of PAH include vascular growth factors (33), BMPR2 (34,35), apoptosis (mutant survivin) (20), calcitonin-gene related peptide (36), and voltage-gated potassium channels (21). However, only a hybrid strategy based on the administration of bone marrow–derived endothelial-like progenitor cells overexpressing eNOS is currently in the clinical study (37). This reflects the complexity of advancing pre-clinical research in the area of gene or cell therapy in PH as well as the need for testing new interventions in relevant animal models of disease (17).

A major aspect in the pre-clinical development of gene therapy as a treatment modality is an optimal delivery method. Due to potential off-target expression of the transgene, organ specificity is a major goal to prevent adverse effects, and to this extent, large animal models have provided an invaluable framework in the field of cardiovascular gene therapy (38). We chose airway delivery of viral vectors on the basis of a number of previous rodent studies that demonstrated feasibility and selectivity to target the distal pulmonary vasculature (12,15,20,21,30,32–34,36,39). The present study is the first to report feasibility of AAV1 gene delivery to the distal pulmonary vessels in a large animal model using an intratracheal sprayer device. A previous report showed the advantages of such a device to deliver AAV vectors to the distal airway compared to oral nebulization or direct catheter instillation. This study also reported that the particle dimensions generated by the microsprayer (~20 μm) did not affect the viability of AAV particles due to their small size (~20 nm) (40). Thus, optimization and future advances in delivery device technology should further improve the ability to transduce the distal pulmonary vessels and minimize the invasiveness of the procedure.

Safety represents a significant concern in the evaluation of nonconventional treatments such as gene or cell therapy. In recent years, gene therapy studies focusing on chronic disorders have shifted to using recombinant AAV as vectors due to their ability to achieve sustained transgene expression, the fact that no human disease is currently attributed to AAV infection, and the very low integration rate of AAV into the host genome (8). Conversely, frequent AAV exposure in humans has led to a high prevalence of neutralizing antibodies that limit the proportion of patients who are candidates for this therapy and make repeated administrations of the AAV vector inefficient (25,41). In the present study, as seen in clinical trials in patients with cystic fibrosis (42), airway administration of AAV led to a high rate of seroconversion. The inability to perform repeated administrations was considered a major hurdle in the development of gene therapies in cystic fibrosis programs and must be addressed to increase the broad applicability of gene therapies using AAV vectors for PH.

Overall, AAV vectors have shown a good safety profile in several clinical trials (43), leading to the regulatory approval of the first AAV1-based gene therapy to treat a human disease (44). Furthermore, compared with other viral vectors (i.e., adenovirus) used in gene therapy studies, AAVs elicit almost no inflammatory response and are nonpathogenic in humans, although they have a smaller packaging capacity, limiting the size of the transgene. With respect to AAV1.SERCA2a, the first clinical trial of this vector and transgene in patients with advanced HF has been reported (45), including long-term follow-up (~3 years) (46), indicating that this therapy was safe when delivered by intracoronary administration.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

In our model of chronic post-capillary PH, the partial venous banding procedure may lead to remodeling of the banded pulmonary veins with potential implications for cardiopulmonary pressures. Although we investigated pulmonary venous inflow and the PA diastolic pressure at several time points to ensure that there were no differences between animals, we did not assess inferior lung lobe vein remodeling histologically (47). Thus, we cannot exclude an effect of AAV1.SERCA2a on pulmonary vein remodeling. We also believe that PAWP accurately reflects left atrial pressure in our model; however, it is possible that PAWP was elevated artificially due to damping or other measure-related issues. The study was also performed with a small sample size that may have limited power and limited follow-up (8 weeks after gene delivery). Therefore, future studies focusing on long-term efficacy and safety endpoints are warranted prior to advancing airway gene delivery to the clinic.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings indicate that AAV1-based gene therapy was efficacious in PH and position pulmonary vascular SERCA2a gene transfer via aerosol inhalation delivery as a therapeutic modality in PH and other related pulmonary vascular diseases.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

Down-regulation of SERCA2a is associated with progressive distal PA hypertrophic remodeling and RV dysfunction in patients with chronic post-capillary PH. Aerosolized delivery of AAV1.SERCA2a in a large animal model of this disease favorably influences PA remodeling and improves RV function.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Further studies are needed to translate this therapy to patients with this disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank L. Leonardson for her expertise and valuable technical support.

This work is supported by National Institutes of Health grants RO1 HL083156, HL093183, HL119046, and P20HL100396 and a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology Award; contract HHSN268201000045C (to Dr. Hajjar); and National Institutes of Health R01105301 and U01 125215 (to Dr. Leopold). Part of the work was funded by a Leducq Foundation grant (to Dr. Hajjar). Dr. Aguero was supported by the Fundacion Alfonso Martin-Escudero. Dr. Hammoudi was supported by the French Federation of Cardiology; and has received a research grant from Laboratoires Servier. Dr. Maron is the recipient of an investigator-initiated grant from Gilead Sciences. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose. Drs. Leopold and Hajjar contributed equally to this work. David A. Dicheck, MD, served as Guest Editor for this paper.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- AAV1.SERCA2a

recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 1 carrying the human SERCA2a transgene

- IQR

interquartile range

- PAH

pulmonary arterial hypertension

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- RV

right ventricle

- SERCA2a

sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a

APPENDIX

For a supplemental Methods section as well as supplemental figures and tables, please see the online version of this article.

Footnotes

Listen to this manuscript’s audio summary by JACC Editor-in-Chief Dr. Valentin Fuster.

References

- 1.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) Eur Heart J. 2009;30:2493–537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benza RL, Miller DP, Gomberg-Maitland M, et al. Predicting survival in pulmonary arterial hypertension: insights from the Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL) Circulation. 2010;122:164–72. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.898122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van de Veerdonk MC, Kind T, Marcus JT, et al. Progressive right ventricular dysfunction in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension responding to therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2511–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strange G, Playford D, Stewart S, et al. Pulmonary hypertension: prevalence and mortality in the Armadale echocardiography cohort. Heart. 2012;98:1805–11. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vachiery JL, Adir Y, Barbera JA, et al. Pulmonary hypertension due to left heart diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D100–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado JF, Conde E, Sanchez V, et al. Pulmonary vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension due to chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2005;7:1011–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taichman DB, Ornelas J, Chung L, et al. Pharmacologic therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension in adults: chest guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2014;146:449–75. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hajjar RJ. Potential of gene therapy as a treatment for heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:53–61. doi: 10.1172/JCI62837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ginn SL, Alexander IE, Edelstein ML, et al. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide to 2012—an update. J Gene Med. 2013;15:65–77. doi: 10.1002/jgm.2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reynolds PN. Gene therapy for pulmonary hypertension: prospects and challenges. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2011;11:133–43. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2011.542139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Champion HC, Bivalacqua TJ, Greenberg SS, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer of endothelial nitricoxide synthase (eNOS) partially restores normal pulmonary arterial pressure in eNOS-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13248–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182225899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gubrij IB, Martin SR, Pangle AK, et al. Attenuation of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension by luminal adeno-associated virus serotype 9 gene transfer of prostacyclin synthase. Hum Gene Ther. 2014;25:498–505. doi: 10.1089/hum.2013.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuhr FK, Smith KA, Song MY, et al. New mechanisms of pulmonary arterial hypertension: role of Ca(2)(+) signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1546–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00944.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawase Y, Hajjar RJ. The cardiac sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase: a potent target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:554–65. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hadri L, Kratlian RG, Benard L, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of AAV1.SERCA2a in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2013;128:512–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stenmark KR, Meyrick B, Galie N, et al. Animal models of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the hope for etiological discovery and pharmacological cure. 2009;297:L1013–32. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00217.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sutendra G, Michelakis ED. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: challenges in translational research and a vision for change. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:208sr5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguero J, Ishikawa K, Hadri L, et al. Characterization of right ventricular remodeling and failure in a chronic pulmonary hypertension model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H1204–15. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00246.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguero J, Ishikawa K, Fish KM, et al. Combination proximal pulmonary artery coiling and distal embolization induces chronic elevations in pulmonary artery pressure in swine. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0124526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMurtry MS, Archer SL, Altieri DC, et al. Gene therapy targeting survivin selectively induces pulmonary vascular apoptosis and reverses pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1479–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI23203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pozeg ZI, Michelakis ED, McMurtry MS, et al. In vivo gene transfer of the O2-sensitive potassium channel Kv1.5 reduces pulmonary hypertension and restores hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction in chronically hypoxic rats. Circulation. 2003;107:2037–44. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000062688.76508.B3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karakikes I, Hadri L, Rapti K, et al. Concomitant intravenous nitroglycerin with intracoronary delivery of AAV1.SERCA2a enhances gene transfer in porcine hearts. Mol Ther. 2012;20:565–71. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishikawa K, Fish KM, Tilemann L, et al. Cardiac I-1c overexpression with reengineered AAV improves cardiac function in swine ischemic heart failure. Mol Ther. 2014;22:2038–45. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaski BE, Jessup ML, Mancini DM, et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID Trial), a first-in-human phase 1/2 clinical trial. J Card Fail. 2009;15:171–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapti K, Louis-Jeune V, Kohlbrenner E, et al. Neutralizing antibodies against AAV serotypes 1, 2, 6, and 9 in sera of commonly used animal models. Mol Ther. 2012;20:73–83. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck SE, Laube BL, Barberena CI, et al. Deposition and expression of aerosolized rAAV vectors in the lungs of Rhesus macaques. Mol Ther. 2002;6:546–54. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pereda D, Garcia-Alvarez A, Sanchez-Quintana D, et al. Swine model of chronic post-capillary pulmonary hypertension with right ventricular remodeling: long-term characterization by cardiac catheterization, magnetic resonance, and pathology. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7:494–506. doi: 10.1007/s12265-014-9564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hadri L, Bobe R, Kawase Y, et al. SERCA2a gene transfer enhances eNOS expression and activity in endothelial cells. Mol Ther. 2010;18:1284–92. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, et al. Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension: physiology and pathobiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:D22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Champion HC, Bivalacqua TJ, D’Souza FM, et al. Gene transfer of endothelial nitric oxide synthase to the lung of the mouse in vivo: effect on agonist-induced and flow-mediated vascular responses. Circ Res. 1999;84:1422–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.12.1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito T, Okada T, Mimuro J, et al. Adenoassociated virus–mediated prostacyclin synthase expression prevents pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 2007;50:531–6. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.091348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagaya N, Yokoyama C, Kyotani S, et al. Gene transfer of human prostacyclin synthase ameliorates monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Circulation. 2000;102:2005–10. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.16.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Partovian C, Adnot S, Raffestin B, et al. Adenovirus-mediated lung vascular endothelial growth factor overexpression protects against hypoxic pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:762–71. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.6.4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McMurtry MS, Moudgil R, Hashimoto K, et al. Overexpression of human bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 does not ameliorate monocrotaline pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L872–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00309.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds AM, Holmes MD, Danilov SM, et al. Targeted gene delivery of BMPR2 attenuates pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:329–43. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00187310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Champion HC, Bivalacqua TJ, Toyoda K, et al. In vivo gene transfer of preprocalcitonin gene– related peptide to the lung attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in the mouse. Circulation. 2000;101:923–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Granton J, Langelben D, Kutryk MB, et al. Endothelial NO synthase gene-enhanced progenitor cell therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: The PHACeT Trial. Circ Res. 2015;117:645–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.305951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishikawa K, Aguero J, Naim C, et al. Percutaneous approaches for efficient cardiac gene delivery. J Cardiovasc Trans Res. 2013;6:649–59. doi: 10.1007/s12265-013-9479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Budts W, Pokreisz P, Nong Z, et al. Aerosol gene transfer with inducible nitric oxide synthase reduces hypoxic pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats. Circulation. 2000;102:2880–5. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.23.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beck SE, Laube BL, Barberena CI, et al. Deposition and expression of aerosolized rAAV vectors in the lungs of rhesus macaques. Mol Ther. 2002;6:546–54. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Louis Jeune V, Joergensen JA, Hajjar RJ, et al. Pre-existing anti–adeno-associated virus antibodies as a challenge in AAV gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther Methods. 2013;24:59–67. doi: 10.1089/hgtb.2012.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moss RB, Rodman D, Spencer LT, et al. Repeated adeno-associated virus serotype 2 aerosol-mediated cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator gene transfer to the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Chest. 2004;125:509–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufmann KB, Büning H, Galy A, et al. Gene therapy on the move. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:1642–61. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201202287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaudet D, Methot J, Dery S, et al. Efficacy and long-term safety of alipogene tiparvovec (AAV1-LPLS447X) gene therapy for lipoprotein lipase deficiency: an open-label trial. Gene Ther. 2013;20:361–9. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jessup M, Greenberg B, Mancini D, et al. Calcium Upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID): A phase 2 trial of intracoronary gene therapy of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2011;124:304–13. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.022889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zsebo K, Yaroshinsky A, Rudy JJ, et al. Long-term effects of AAV1/SERCA2a gene transfer in patients with severe heart failure: analysis of recurrent cardiovascular events and mortality. Circ Res. 2014;114:101–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerges C, Gerges M, Lang MB, et al. Diastolic pulmonary vascular pressure gradient: a predictor of prognosis in “out-of-proportion” pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2013;143:758–66. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.