Abstract

Introduction

Insulin analog glargine (GLA) has been available as one of the therapeutic options for patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus to enhance glycemic control. Studies have shown that a decrease in the frequency of hypoglycemic episodes improves the quality of life (QoL) of diabetic patients. However, there are appreciable acquisition cost differences between different insulins. Consequently, there is a need to assess their impact on QoL to provide future guidance to health authorities.

Method

A systematic review of multiple databases including Medline, LILACS, Cochrane, and EMBASE databases with several combinations of agreed terms involving randomized controlled trials and cohorts, as well as manual searches and gray literature, was undertaken. The primary outcome measure was a change in QoL. The quality of the studies and the risk of bias was also assessed.

Results

Eight studies were eventually included in the systematic review out of 634 publications. Eight different QoL instruments were used (two generic, two mixed, and four specific), in which the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) was the most used. The systematic review did not consistently show any significant difference overall in QoL scores, whether as part of subsets or combined into a single score, with the use of GLA versus neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin. Only in patient satisfaction measured by DTSQ was a better result consistently seen with GLA versus NPH insulin, but not using the Well-being Inquiry for Diabetics (WED) scale. However, none of the cohort studies scored a maximum on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for quality, and they generally were of moderate quality with bias in the studies.

Conclusion

There was no consistent difference in QoL or patient-reported outcomes when the findings from the eight studies were collated. In view of this, we believe the current price differential between GLA and NPH insulin in Brazil cannot be justified by these findings.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40271-017-0291-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points for Decision Makers

| In Brazil, insulin glargine (GLA) has been available as a treatment option versus neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin for a number of years to enhance glycemic control and patients’ quality of life as an easier preparation to administer than NPH insulin. |

| A systematic review failed to consistently show any significant difference in quality of life scores between GLA versus NPH insulin. Only in patients’ satisfaction measured by the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire was a better result consistently seen with GLA versus NPH insulin. However, there were concerns with the quality of the studies. |

| Based on our findings, we believe the current price differential between the two insulin preparations in Brazil cannot be justified within its universal healthcare system. |

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic and complex disease that requires continuous medical care. DM can be subdivided into several etiological types, with Type 1 DM (T1DM) and Type 2 DM (T2DM) being the most prevalent [1]. T1DM is characterized by the destruction of the islets of Langerhans and insulin-secreting β1 cells in the pancreas mediated by the immune response, and its treatment is based on the replacement of deficient or non-existent insulin [2].

There are a range of insulins currently available for the treatment of patients with T1DM. These include both neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH), which has an intermediate action profile, and longer-acting insulins such as analog glargine (GLA). NPH is usually the first-choice treatment when the diagnosis of T1DM is confirmed in view of typically appreciably lower costs than the analogs, and similar effectiveness [3–7]. GLA was developed as a better alternative to basal insulin, aiming for a peak-free preparation and with prolonged action, which mimics the insulin secretion of individuals without DM. This has resulted in a decrease in episodes of hypoglycemia as well as better glycemic control, mainly glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), compared with NPH insulin in some publications [8–12], with HbA1c the main predictor of the effectiveness of T1DM treatment. The monitoring and maintenance of HbA1c at levels ≤ 7% is fundamental to reducing chronic microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and macrovascular complications (peripheral arterial disease, carotid disease, and coronary artery disease), as well as acute complications, which includes episodes of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia associated with T1DM [2, 13].

However, in two systematic reviews (SRs), no benefits for GLA compared with NPH insulin were found for the main outcome measure, HbA1c, in terms of effectiveness as well as safety [4, 14]. Similar results were seen in a recent cohort study in Brazil [15]. The difference in the findings may partly be due to the study sponsors, with studies with conflicts of interest favoring GLA versus those studies without conflicts of interest [14]. Another important aspect is the price difference that can exist between GLA and NPH insulin. In the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, there was an increase of just under 300% in the costs of insulins to the State’s Department of Health after the incorporation of GLA. This resulted in approximately US$6 million being spent on insulins in 2012, exacerbated by the price difference between NPH and GLA in Brazil at over 500% [4, 15].

Improved quality of life (QoL), defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a way of measuring the individual’s perception of their life position, cultural aspects, personal goals, and concerns [16], is fundamental to understanding the notion of health. Consequently, this is an important variable in clinical practice, as well as helping with decisions on priority setting and resource allocation. The measurement of the impact of different treatments on QoL, as well as its improvement, is one of the expected humanistic results of healthcare practices and public policies in the fields of health promotion and disease prevention, especially chronic diseases such as T1DM [16, 17]. Several instruments have been used to evaluate the impact of different treatments on the QoL of patients with diabetes [18]. Effective control of T1DM, and minimal problems with insulin therapy, tend to favorably influence patients’ QoL [19–22].

It is hypothesized that the use of GLA versus NPH insulin would promote better QoL, as GLA insulin could lead to a decrease in the episodes of hypoglycemia and would also cause less discomfort to patients. There have been several SRs to assess differences in effectiveness and safety of GLA versus NPH insulins [14, 23–25]. However, we did not identify any SRs in the literature measuring the impact on patients’ QoL as a primary outcome, although our unit and others have assessed the impact of T1DM on patients’ health-related QoL (HRQoL) [17]. In addition, we are aware that Plank et al. [23], in their SR, also assessed the impact of the different insulins on patients’ QoL but found no evidence of an improvement in patients’ scores with GLA versus NPH insulins with the instruments used. Vardi et al. [24] in their SR for the Cochrane Collaboration showed higher scores in patient satisfaction favoring GLA; however, when using the Audit of Diabetes-Dependent Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (ADDQoL) instrument, no differences were seen between the two insulins. Assessing the impact of the two insulins on QoL is important given the current differences in acquisition costs between GLA and NPH insulin in Brazil, and the need to maximize health gain within finite resources in the current economic situation. Consequently, we aimed to evaluate the impact on QoL of T1DM patients using either GLA or NPH insulin through an SR of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and observational studies. The findings will be used to further guide pricing and other strategies for insulins in Brazil to help maximize the use of available resources for these patients. Within Brazil, CONITEC (The national Committee for Health Technology Incorporation) currently assess the potential listing and funding of new medicines based on their relative efficacy, safety, costs, and budget impact versus current standards in all or defined populations. This is based on published evidence. Subsequently, at the state level, committees including the Commission of Pharmaceuticals and Therapeutics (Comissão de Farmácia e Terapêutica–CFT) in Minas Gerais, further evaluate their relative value versus current standards for inclusion within state-wide agreed treatment guidance, with prescribing against the agreed guidance subsequently monitored [4].

Methods

An SR of the literature was undertaken according to the methodological guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [26]. SRs are seen as important for scientific research as they typically reflect the best evidence on a topic, with the findings subsequently used to improve treatments and policy decisions where pertinent.

The SR protocol for this study was registered in the PROSPERO database (International Prospecting Register of Ongoing Systematic Reviews) under nº CRD42016046875 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_reord.asp?ID=CRD42016046875).

Databases and Search Strategy

Available publications were selected until January 2017 in the following databases: MEDLINE (PubMed), Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences (LILACS), Cochrane Library, and EMBASE. Several combinations of terms were used following the PICO (population, intervention, comparison and outcome) strategy: T1DM, GLA, NPH and QoL (Table 1). As a complement to the electronic search, a manual search was carried out in all included studies, as well as in the periodicals Diabetes Care and Quality of Life Research, in the years 2000 to December 2016, by two independent reviewers. A search of studies in the gray literature was also carried out in the Digital Library of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), and in the thesis and dissertations bank of the Coordination of Improvement of Personnel of Higher Education (CAPES) and the Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations. Table 1 describes the overview of the search strategy based on the Medline (PubMed) database, with more details contained in Appendix 1 (see electronic supplementary material). Key terms included T1DM, GLA, NPH, and QoL.

Table 1.

Search strategies used to undertake the systematic review

| Electronic databases | Search strategy | Recovered studies |

|---|---|---|

| Medline (PubMed) | ((((((((((((((((((Diabetic Ketoacidosis[MeSH Terms]) OR Diabetes Mellitus, Type 1[MeSH Terms]) OR Diabetes Mellitus, Insulin*Dependent[Text Word]) OR Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus[Text Word]) OR Juvenile-Onset Diabetes Mellitus[Text Word]) OR Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus[Text Word]) OR Sudden-Onset Diabetes Mellitus[Text Word]) OR Diabetes Mellitus, Type I[Text Word]) OR IDDM[Text Word]) OR Insulin*Dependent Diabetes Mellitus 1[Text Word]) OR Juvenile*Onset Diabetes[Text Word]) OR Brittle Diabetes Mellitus[Text Word]) OR Ketosis-Prone Diabetes Mellitus[Text Word]) OR Diabetes, Autoimmune[All Fields] AND Text Word) OR Autoimmune Diabetes[Text Word]) NOT diabetes insipidus[MeSH Terms])) AND (((((((Insulin, Isophane[MeSH Terms]) OR Isophane Insulin[Text Word]) OR NPH Insulin[Text Word]) OR NPH[Text Word]) OR Protamine Hagedorn Insulin[Text Word]) OR Neutral Protamine Hagedorn Insulin[Text Word]))) OR (((((((LY2963016 insulin glargine [Supplementary Concept]OR glargine[Text Word]) OR lantus[Text Word]) OR insulin glargine[Text Word]) OR HOE*901[Text Word])) OR “Insulin, Long-Acting”[Mesh])) AND (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((“quality of life”[MeSH Terms]) OR “quality of life”[Text Word]) OR “life qualities”[Text Word]) OR “life quality”[Text Word]) OR “health related quality of life”[Text Word]) OR “qol”[Text Word]) OR “hrqol”[Text Word]) OR “hrqol”[Text Word]) OR ((“quality of well being scale self administered”[Text Word] OR “quality of well being scale self administeredqwbsa”[Text Word]))) OR “qwb-sa”[Text Word]) OR “euroqol”[Text Word]) OR “Eq 5d”[Text Word]) OR “Eq 5d 3 l”[Text Word]) OR “the medical outcomes study 36 item short form health survey”[Text Word]) OR “sf 36”[Text Word]) OR “world health organization quality of life”[Text Word]) OR ((“whoqol”[Text Word] OR “whoqol 100”[Text Word] OR “whoqolbref”[Text Word] OR “whoqolbref questionnaire”[Text Word]))) OR “quality adjusted life years”[Text Word]) OR “qalys”[Text Word]) OR “nottingham health profile”[Text Word]) OR ((“sickness impact profile”[Text Word] OR “sickness impact profile sip”[Text Word]))) OR “dartmouth coop”[Text Word]) OR “hrql”[Text Word]) OR “health utilities index”[Text Word]) OR “hui”[Text Word]) OR “short form 6d”[Text Word]) OR “sf 6d”[Text Word]) OR ((“diabetes 39”[Text Word] OR “diabetes 39 questionnaire”[Text Word]))) OR ((“diabetes quality of life measure”[Text Word] OR “diabetes quality of life questionnaire”[Text Word]))) OR “dqol”[Text Word]) OR ((“audit of diabetes dependent quality of life”[Text Word] OR “audit of diabetes dependent quality of life addq”[Text Word]))) OR ((“addqol”[Text Word] OR “addqol questionnaire”[Text Word]))) OR “diabetes attitude scale”[Text Word]) OR “diabetes knowledge test”[Text Word]) OR ((“diabetes empowerment scale”[Text Word] OR “diabetes empowerment scale short”[Text Word] OR “diabetes empowerment scale short form”[Text Word]))) OR ((“michigan neuropathy screening instrument”[Text Word] OR “michigan neuropathy screening instrument questionnaire”[Text Word]))) OR ((“diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire”[Text Word] OR “diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire score”[Text Word] OR “diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire scores”[Text Word] OR “diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire status”[Text Word] OR “diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire status version”[Text Word]))) | 259 |

Selection of Studies and Eligibility Criteria

RCTs and cohort studies (prospective and retrospective) were subsequently selected for the SR from the papers identified that assessed the impact of GLA versus NPH insulin on patients’ QoL.

We excluded cohort studies and RCTs that did not concentrate on QoL as the primary outcome measure, studies with oral hypoglycemic medicines concomitant with insulin in patients with T1DM, as well as studies with a sample of 30 individuals or less or that had a follow-up time of < 4 weeks. 4 weeks was considered the minimum time to effectively measure the impact of different treatments on patients’ QoL based on an earlier study from our group [14].

Data Collection and Analysis

Initially, the recovered studies in the databases were allocated on a single basis to exclude those duplicated by the EndNote software. Thereafter, two independent reviewers (PA and TS) evaluated the titles (Phase 1), the abstracts (phase 2) and the full text (phase 3). A third reviewer (VA) was asked to solve possible discordances. Sociodemographic characteristics of the patients, treatment period, and QoL were extracted in duplicate in a form, previously formulated and tested in Excel, for this purpose. A qualitative synthesis of the studies was performed, since the heterogeneity of the measurement instruments and the data did not make a quantitative synthesis possible as undertaken with previous SRs concentrating on issues such as effectiveness when measuring HbA1c levels and hypoglycemic episodes [14, 23–25].

The methodological quality of the cohort studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. This scale was originally developed to evaluate the quality of observational studies. It contains eight items. These include representativeness of the sample in the exposed cohort, selection of the unexposed cohort, exposure by the type of measure used (e.g., secure records or structured interviews), how the outcome of interest was assessed, whether the follow-up of the study was long enough for the hypothesis of the results to occur, and if there was adequate follow-up of the cohorts. Stars are assigned to each completed item, with the highest possible score being nine. A score above six means that the study has high methodological quality [27].

In order to assess the risk of bias in RCTs, the current recommendation of the Cochrane Collaboration is to use the Revman software (Review Manager 5.3). This program consists of two parts, in which seven domains are distributed: random sequence generation, concealment of allocation, blinding of participants and professionals, incomplete outcomes, reporting of outcome, and other sources of bias [28]. The sources of funding for the identified studies were examined for potential sources of bias, as the influence of this on the findings and their implications was seen in a previous SR comparing the different insulin types [14]. Comments regarding any conflict of interest, study financing by a manufacturer of any of the insulins, or if any of the authors were related to the pharmaceutical industry or had received fees from them, were examined and documented.

Quality-of-Life Scales

A number of QoL scales have been used in the literature to assess the impact of different treatment options on patients’ QoL in studies, including both generic and disease-specific instruments. The most prevalent scales used for studies assessing the QoL of patients with diabetes include:

The mixed Well-Being Questionnaire 28 (W-BQ28), which has the following domains: positive perception of well-being, negative perception of well-being, energy, and stress. For the specific part, these included positive perception of well-being related to DM, negative perception of well-being related to DM, and stress related to DM [29, 30].

The Well-Being Questionnaire (WBQ22), which provides a general welfare score comprising 22 items and has the following domains: depression, anxiety, energy, and positive perception of well-being. There is also WBQ12, which is a shortened version of WBQ22 with 12 items and four domains: negative well-being, energy, positive well-being, and general well-being [30].

The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ). The DTSQs instrument evaluates treatment satisfaction at the beginning, with DTSQc used at the end of follow-up. DTSQ presents three domains: satisfaction with current treatment, perceived frequency of hypoglycemia, and perceived frequency of hyperglycemia. DTSQc uses the same domains as DTSQs, but it has different response options and asks respondents to assess changes in current treatment satisfaction (endpoint) compared with baseline in order to overcome a possible ceiling effect [31].

The Well-being Inquiry for Diabetics (WED) evaluates four areas of psychological well-being: (a) somatic symptoms related to diabetes and physical functioning; (b) concerns related to diabetes and emotional state; (c) mental health; (d) family relationships, friends network, and society [32].

The Diabetes Quality of Life Measure (DQOL) presents four domains: impact, satisfaction, concerns about DM, and concerns about social and vocational life [33].

The Audit of Diabetes-Dependent Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (ADDQoL), an instrument that has four domains: social and professional life, average weighted impact (AWI), specific QoL for DM, and current QoL that refers to the overall score [34].

Results

Study Selection for the Systematic Review

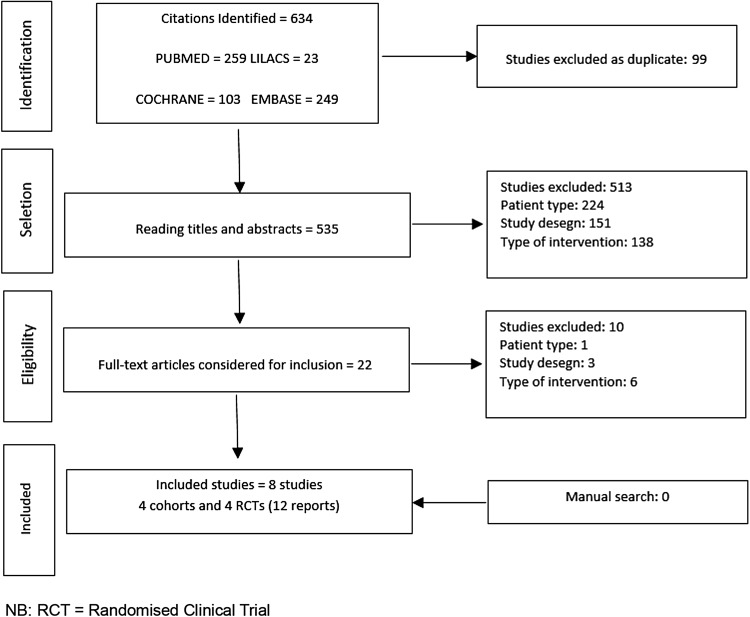

We found 634 publications in the electronic databases (Fig. 1). After exclusion of 99 duplicates, 535 articles were selected for title and abstract analysis. Of these, 513 publications were subsequently excluded for a variety of reasons (Fig. 1), resulting in 22 publications for complete reading. Manual searches, which included analyzing all volumes and chosen periodicals page by page without the help of any search engine and checking all references in the SRs, did not return any relevant further studies for inclusion. Finally, 8 studies with 11 publications (9 papers and 2 conference abstracts) remained for the SR (Fig. 1). Studies were excluded mainly because they included patients with T2DM; used insulins other than GLA and NPH, or concentrated on oral antidiabetics alone, or patients were taking these concomitantly with injectable insulins; were not cohorts or RCTs; or did not use any instrument to measure QoL.

Fig. 1.

Overview of the flowchart of the selection of included studies

Study Characteristics

From the eight included studies, four cohorts [35–38] (two retrospective [35, 38], two prospective studies [36, 37]) and four RCTs [39–42] were identified that met our criteria (Fig. 1). The follow-up time of patients in these eight studies ranged from 6 to 24 months; three cohort studies [35–37] had a long follow-up period (12 months or more) and one [38] had an intermediate time (6–12 months). All RCTs [39–42] had a long follow-up time (> 12 months). Three studies [35, 37, 39] reported no conflicts of interest and five [36, 38, 40–42] declared a conflict of interest with pharmaceutical companies funding the studies or fee-paying the authors. The studies evaluated approximately 1855 individuals to compare the QoL among patients with T1DM who used either GLA or NPH insulin.

Concerning the characteristics of individuals with T1DM in the identified studies, patients’ ages ranged from 5 to 40 years, on average. Two studies evaluated the QoL of pediatric individuals [35, 38] and six analyzed the impact of the different insulin preparations on the QoL of adult patients [36, 37, 39–42]. The studies had a majority of men, with the duration of T1DM ranging from 2.9 (SD ± 0.2) to 22.3 (SD ± 15.5) years (Table 2).

Table 2.

General characteristics of included studies

| Study | Design | Instruments | Number of instruments | Number of participants | Country | Study scope | Funding | Conflicts of interest | Study duration (months) | Classification durationa | Newcastle–Ottawa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Päivärinta et al. [35] | Retrospective cohort | DTSQs | 1 | 62 (GLA = 35/NPH = 27) | Finland | Single center | NR | NR | 24 | Long | 7 |

| Gallen and Carter [36] | Prospective cohort | DTSQs, W-BQ28/WBQ12 | 2 | 85 (GLA = 85/NPH = 85) | England | Single center | SBDRF | Yes | 12 | Long | 5 |

| Manini et al. [37] | Prospective cohort | WED | 1 | 87 (GLA = 47/NPH = 47); NPH CONTROL = 40 | Italy | Single center | NR | NR | 8 | Long | 4 |

| Dixon et al. [38] | Retrospective cohort | DQOL | 1 | 128 (GLA = 64/NPH = 64) | USA | Single center | GCRCP, NCRR, NIH and CDF | NR | 6 | Intermediate | 8 |

| Bolli et al. [39] | RCT | WED | 1 | 175 (GLA + LIS = 85/GLA + LIS = 90) | Italy | Multicentric | Sanofi Aventis | Yes | 7.5 | Long | |

| Witthaus et al. (2001) [40] | RCT | DTSQs, WBQ22 | 2 | 517 (GLA + HUMAN = 261/NPH + HUMAN = 256) | 10 European countries | Multicentric | Aventis Pharma | Yes | 7 | Long | |

| Ashwell et al. [41] | RCT | DTSQs/DTSQc, ADDQoL | 2 | 56 (GLA + LIS = 22/NPH + HUMAN = 26) | England | Multicentric | Sanofi Aventis | Yes | 8 | Long | |

| Polonsky et al. [42] | RCT | DTSQs | 1 | 771 (GLA = 393/NPH + REGULAR = 378) | 12 European countries + USA | Multicentric | Sanofi Aventis | Yes | 7 | Long |

ADDQoL Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life Questionnaire, CDF Children’s Diabetes Foundation, DQOL Diabetes Quality of Life Measure, DTSQ Diabetes Quality of Life Measure (DTSQs evaluates treatment satisfaction at the beginning with DTSQc measuring it at the end of follow-up), GCRCP General Clinical Research Centers Program, GLA glargine, LIS lispro, NCRR National Centers for Research Resources, NIH National Institutes of Health, NPH neutral protamine Hagedorn, NR not reported, RCT randomized clinical trial, SBDRF South Buckinghamshire Diabetes Research Fund, WBQ22 Well-Being Questionnaire–22 items (WBQ12 = 12 items), W-BQ28 mixed Well-Being Questionnaire 28, WED Well-Being Inquiry for Diabetics

aClassification of Duration of follow-up = 1–6 months as short, 6–12 months as intermediate, and > 12 months as long

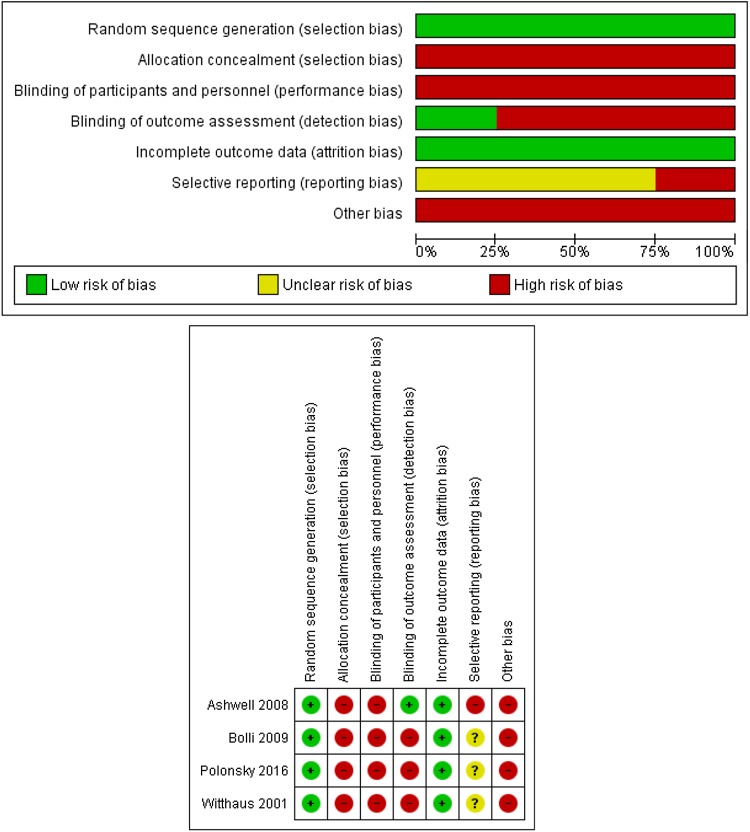

Methodological Quality

None of the cohort studies scored a maximum of nine stars on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale, and in general, the studies obtained only a moderate quality score (Table 2). In addition, none of the studies had a low risk of bias in all seven domains. In the second domain, about allocation concealment, all studies had a high risk of bias, since the insulin bottles were identifiable. For the third and fourth domains, on blinding of participants, professionals, and evaluators, all studies had a high risk of bias (open-label). Only one study blinded the data raters. Regarding the sixth domain, about reporting of selective outcomes, one study did not report in the protocol that the QoL of patients would be collected in the Electronic case records, being considered a high risk of bias. The others were judged as having insufficient information. In the seventh domain, dealing with other sources of bias, all the studies had some kind of link with the pharmaceutical industry, declared or otherwise, being considered a high risk of bias. In general, the four RCTs had poor methodological quality (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Cochrane Collaboration bias risk graph

Data Synthesis

The eight studies used eight instruments, in total, to evaluate the QoL of patients with T1DM comparing GLA and NPH insulins. Two generic instruments were used in the studies. These included W-BQ28 (mixed character) [36], and WBQ22 (generic) [40]. Four specific instruments were used to measure the QoL of patients with T1DM. These included the DTSQs and DTSQc [35, 36, 40–42], DQOL [38], and the ADDQol [42], with a mixed scale—the WED scale [37] —as well.

Findings

We will principally document the impact of the different insulin preparations on QoL with key details incorporated into Tables 2 and 3, which include the study design, study population and numbers, the QoL instruments used and their scores, any conflicts of interest, study duration, and the quality of the studies.

Table 3.

Efficacy, effectiveness, and quality of life of included studies

| Study and instrument | Domains | Score | p Value | HbA1c (%) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NPH | GLA | NPH | GLA | ||||

| Päivärinta et al. [35] | |||||||

| DTSQs | Satisfaction with treatment | NR | NR | NR | 8.4 | 8.4 | NS |

| Hypoglycemia perception | NR | NR | |||||

| Perception of hyperglycemia | NR | NR | |||||

| Gallen and Carter [36] | |||||||

| W-BQ28 | Negative perception of well-being | NR | NR | NS | 8.4 | 7.76 | 0.006* |

| Energy | NR | NR | 0.001* | ||||

| Total well-being | NR | NR | 0.032* | ||||

| Stress | NR | NR | NS | ||||

| Negative perception of welfare with DM | NR | NR | NS | ||||

| Stress related to DM | NR | NR | NS | ||||

| Diabetes-related positive well-being | NR | NR | 0.006* | ||||

| DTSQs | Satisfaction with treatment | 23.7 (SD ± 0.85) | 28.1 (SD ± 0.87) | 0.001* | |||

| Perception of hypoglycemia | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Perception of hyperglycemia | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Manini et al. [37] | |||||||

| WED | Symptoms | 15.3 (SD ± 2.7) | 16.1 (SD ± 2.4) | 0.040* | 8.4 | 7.6 | 0.0001* |

| Discomfort | 13.1 (SD ± 3.0) | 13.4 (SD ± 3.3) | 0.019* | ||||

| Serenity | 13.9 (SD ± 1.9) | 14.5 (SD ± 1.5) | 0.197 | ||||

| Impact | 29.6 (SD ± 4.7) | 31.1 (SD ± 6.1) | 0.0002* | ||||

| Total score | 71.9 (SD ± 10.7) | 75.1 (SD ± 11.4) | 0.0002* | ||||

| Dixon et al. [38] | |||||||

| DQOL | Total score | 1 (SD ± 1) | 1 (SD ± 1) | NS | 8.3 | 8.7 | 0.05 |

| Impact | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Satisfaction | 1.9 (SD ± 0.6) | 1.9 (SD ± 0.6) | NS | ||||

| Concerned with DM | 2.2 (SD ± 0,5) | 2.2 (SD ± 0.5) | NS | ||||

| Bolli et al. [39] | |||||||

| WED | Impact | 80 (73–85) | 77 (73–82) | NS | 7.26 | 7.26 | NS |

| Satisfaction | 32 (27–38) | 31 (27–35) | NS | ||||

| General worries | 32 (27–38) | 32 (27–34) | NS | ||||

| Diabetes-related worries | 31 (25–34) | 32 (27–34) | 0.05 | ||||

| Witthaus et al. [40] | |||||||

| DTSQs | Satisfaction with treatment | 27.53 | 29.11 | 0.001* | NR | NR | NR |

| Perception of hypoglycemia | 2.25 | 2.20 | NS | ||||

| Perception of hyperglycemia | 2.70 | 2.25 | 0.038* | ||||

| W-BQ22 | General well-being | 50.97 | 51.56 | NS | |||

| Depression | 3.34 | 3.31 | NS | ||||

| Anxiety | 3.67 | 3.67 | NS | ||||

| Energy | 8.31 | 8.82 | NS | ||||

| Positive perception of well-being | 13.53 | 13.72 | NS | ||||

| W-BQ12 | General well-being | 50.52 | 51.12 | NS | |||

| Negative perception of well-being | NR | NR | NS | ||||

| Positive perception of well-being | 12.97 | 13.57 | NS | ||||

| Ashwell et al. [41] | |||||||

| DTSQs | Satisfaction with treatment | 23.7 (SD ± 0.7) | 32.3 (SD ± 0.7) | 0.001* | 7.5 | 8.0 | 0.001* |

| Perception of hypoglycemia | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Perception of hyperglycemia | 4.0 (SD ± 0.2) | 2.7 (SD ± 0.2) | 0.001 | ||||

| DTSQc | Satisfaction with treatment | 13.5 (SD ± 1.7) | − 0.4 (SD ± 1.8) | 0.001* | |||

| Perception of hypoglycemia | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Perception of hyperglycemia | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| ADDQol | Social life and work life | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Average weighted impact (AWI) | − 1.7 (SD ± 0.1) | − 1.4(SD ± 0.1) | 0.003* | ||||

| QoL specific for DM | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Current QoL | 1.3 (SD ± 0.1) | 1.6 (SD ± 0.1) | 0.014 | ||||

| Polonsky et al. [42] | |||||||

| DTSQs | Satisfaction with treatment | 28.40 | 29.6 | 0.006* | 7.8 | 7.9 | 0.719 |

| Perception of hypoglycemia | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Perception of hyperglycemia | NR | NR | NR | ||||

ADDQoL Audit of Diabetes Dependent Quality of Life Questionnaire, DM diabetes mellitus, DQOL Diabetes Quality of Life Measure, DTSQ Diabetes Quality of Life Measure (DTSQs evaluates treatment satisfaction at the beginning with DTSQc measuring it at the end of follow-up), GLA glargine, NPH neutral protamine Hagedorn, NR not reported, NS not significant, QoL quality of life, SD standard deviation, WBQ22 Well-Being Questionnaire–22 items (WBQ12 = 12 items), W-BQ28 mixed Well-Being Questionnaire–28, WED Well-Being Inquiry for Diabetics

*p < 0.05

In the study by Päivärinta et al. [35], there was no statistical difference between the insulins using the DTSQs. There was also no statistically significant difference in HbA1c levels between the two insulins.

Gallen and Carter [36] observed differences between baseline and the endpoints in some of the parameters studied using W-BQ28 and DTSQs, including well-being and energy, favoring GLA. The other domains showed no differences in the QoL of GLA compared with NPH insulin. When the DTSQs instrument was used, a statistically significant difference in satisfaction between the treatments was observed. In the other domains, no difference in QoL was observed between GLA and NPH. Overall, GLA had a significantly favorable impact on HbA1c compared with NPH insulins.

Manini et al. [37] found a statistically significant difference in favor of GLA insulin in three out of the four domains of the QoL scale (WED) used: symptoms, discomfort, and impact, with the overall total score statistically favoring GLA. A statistically significant difference was also observed for HbA1c favoring GLA (7.6%) compared with NPH insulin (8.4%).

None of the domains in the study of Dixon et al. [38] using DQOL showed any statistically significant differences in the scores between GLA and NPH insulin on QoL, although borderline significance when looking at HbA1c values.

Only one domain showed a difference in the study of Bolli et al. [39] using the WED, with no difference seen in HbA1c values between the two insulins.

In the three instruments used by Witthaus et al. [40], no statistically significant difference was seen in the domains of W-BQ12 and W-BQ22. In the DTSQs, a statistically significant difference was seen in favor of GLA insulin in two out of the four domains: satisfaction with treatment and perception of hypoglycemia.

Ashwell et al. [41] found statistically significant differences in favor of GLA insulin in two out of three domains in DTSQc, with one not recorded. Similarly, with DTSQc, there was one statistically significant difference in favor of GLA insulin with three not recorded. There was also a significant difference favoring GLA in two out of the three domains in the ADDQoL. There was also a statistically significant difference in terms of HbA1c favoring GLA.

Polonsky et al. [42] showed a statistically significant difference in favor of GLA insulin using the DTSQs in treatment satisfaction; however, the other domains were not recorded. No statistical difference was seen with HbA1c levels.

Discussion

The most used instrument to assess the impact of GLA versus NPH insulin in our SR was the DTSQs [35, 36, 40–42], similar to Plank et al. [23] and Vardi et al. [24].

In general, there appeared to be no difference overall in QoL comparing GLA and NPH insulins when the score of the domains of the different instruments were evaluated (Table 3), although significant differences were seen in favor of GLA insulin in a number of the domains in the studies by Gallen and Carter [36], Manini et al. [37], Bolli et al. [39], Witthaus et al. [40], Ashwell et al. [41] and Polonsky et al. [42]. This is similar to the SRs of Plank et al. [23] and Vardi et al. [24]. Our findings were also consistent with the SR performed by Singh et al. [25], which evaluated QoL as a secondary result of HbA1c outcome and GLA safety. However, the authors found that patients preferred treatment with insulin analogs over human insulins. This appeared to be due to the flexibility in the dosage between meals and satisfaction with the treatment. There were issues though with the quality of the assessed studies, with typically only moderate scores on the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale [27].

Conflicts of interest are a concern if the judgment of healthcare professionals is influenced by possible financial gain. There can also be concerns with possible ethical and bioethical considerations, centering on patients participating in the research and their well-being [43]. However, we recognize that this is not always the case. Five of the eight studies included in this SR reported some conflict of interest with pharmaceutical companies. These included Gallen and Carter [36]; Witthaus et al. [40]; Bolli et al. [39]; Ashwell et al. [41]; and Polonsky et al. [42]. However, the studies were not totally favorable towards GLA over NPH insulin, although they recorded domains that statistically favored GLA insulin. This can be a concern with one SR reporting that studies with pharmaceutical company sponsorship had a greater relative risk, approximately 27%, of publishing outcomes favorable to the investigated intervention when compared with studies that had independent sources of funding [44]. Favorable results towards GLA insulin were also seen in the SR by Marra et al. [14] in studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies versus those studies where there was no such sponsorship. It should also be emphasized that QoL is a subjective measure and that these conflict of interest relationships between researchers, universities, and pharmaceutical companies can be persuasive, with the findings often favoring the funder [44, 45].

Limitations

We accept this SR only included cohort studies (prospective and retrospective), which may have limited study findings, since this study design has selection bias and confounding factors that are not controlled. There are also concerns with the external validity of RCTs. In addition, RCTs and cohorts were compared, but as no quantitative analysis was performed, statistical heterogeneity was not a problem for data comparison, although it made this more challenging.

Some studies did not present important information, which impaired a meta-analysis of the QoL instruments used in the primary studies. There was also considerable diversity among the instruments used to assess the QoL, which also precluded a full meta-analysis. Some authors also used instruments of satisfaction with treatment (DTSQs) and did not opt for QoL instruments. This is a concern as QoL is a broader construct, as defined by the WHO [16], than just satisfaction with the current treatment. The absence of an appreciable number of papers out of those initially sourced that treated QoL as a primary endpoint also made the meta-analysis and associated comparisons more difficult. Despite these limitations, we believe our findings are robust and provide guidance to the authorities in Brazil and other countries where there are still considerable acquisition cost differences between GLA and NPH insulins.

Conclusion

Despite the limited number of published studies comparing the QoL of patients with T1DM treated with GLA versus NPH insulin, we believe our study findings showing a relative lack of overall difference between the two are robust. This adds to the current debate about the inclusion of GLA insulin in the list of official reimbursed medicines in Brazil whilst there are still considerable acquisition cost differences. GLA, however, seems to be better accepted by users in the domain that assessed satisfaction in T1DM treatment in the DTSQs instrument. However, these findings, which are related to the patient’s therapeutic preference, should be viewed with caution and discussed in the light of other comparisons of GLA versus NPH insulin, which have principally focused on HbA1c and the safety of the different insulins. This especially given some of the concerns with the quality of the reviewed studies coupled with existing considerable differences in acquisition costs between the two insulins in Brazil.

In the future, in patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes, we would like to see more studies assessing the impact of different treatment approaches on the QoL of patients as a primary outcome measure. This can help to formulate appropriate treatment guidelines, including the place of different therapies in treatment regimens alongside considerations of effectiveness and safety. As a result, health authorities will be better able to maximize the health gain of patients within finite resources. These are considerations for the future.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the Research Group on Pharmacoepidemiology (GPFE – Grupo de Pesquisa em Farmacoepidemiologia) of UFMG and the SUS Collaborating Centre for Technology Assessment and Excellence in Health (CCATES – Centro Colaborador do SUS em Avaliação de Tecnologia e Excelência em Saúde). This systematic review is an integral part of the research project “Quality of life and cost-utility analysis of patients with Type I Diabetes Mellitus, users of the analog Glargine”, and was financially supported by the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico – CNPQ).

Author Contributions Statement

PA, TS, AG Jr, VA, FdeAA, LD, AMA and JA designed the concept, PA, TS and VA undertook the systematic review, PA, TS, BBG and JA undertook the drafting of the first manuscript. All authors subsequently contributed to the revision of the first and subsequent manuscripts as well as the revisions following reviewer comments.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Paulo Almeida, Thales Silva, Francisco De Assis Acurcio, Augusto Guerra Júnior, Vania Araújo, Leonardo Diniz, Brian Godman, Alessandra Almeida, and Juliana Alvares declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability

All the papers that were included in the review are cited and can be sourced by other researchers and assessed using similar methodologies.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40271-017-0291-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Paulo H. R. F. Almeida, Email: henriqueribeiro.farm@gmail.com

Thales B. C. Silva, Email: thalescs1@gmail.com

Francisco de Assis Acurcio, Email: acurcio@ufmg.br.

Augusto A. Guerra Júnior, Email: augustoguerramg@gmail.com

Vania E. Araújo, Email: vaniaearaujo@gmail.com

Leonardo M. Diniz, Email: lmdiniz.med@gmail.com

Brian Godman, Phone: 0141 548 3825, Phone: + 46 8 58581068, Email: brian.godman@strath.ac.uk.

Alessandra M. Almeida, Email: alessandraalm@gmail.com

Juliana Alvares, Email: jualvares@gmail.com.

References

- 1.De Oliveira GL, Guerra Junior AA, Godman B, Acurcio FA. Cost-effectiveness of vildagliptin for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Brazil; findings and implications. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;17(2):109–119. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2017.1292852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association (ADA) Standards of medical care in diabetes. Position statement. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):S1–S135. [Google Scholar]

- 3.German Institute for Quality and Efficency in Healthcare (IQWiG). Long-acting insulin analogues in the treatment of diabetes mellitus type 1: Executive Summary Commission No. A05-01. 2010. https://www.iqwig.de/en/projects_results/projects/drug_assessment/a05_01_long_acting_insulin_analogues_in_the_treatment_of_diabetes_mellitus_type_1.1197.html. Accessed 2 July 2017.

- 4.Souza ALC, de Acurcio AF, Junior AAG, do Nascimento RCRM, Godman B, Diniz LM. Insulin glargine in a Brazilian state: should the government disinvest? An assessment based on a systematic review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2014;12(1):19–32. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. World Health Organisation. Review of the Evidence Comparing Insulin (Human or Animal) With Analogue Insulins. 18th Expert Committee on the Selection and Use of Essential Medicines. 1–51. 2011. http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/18/applications/Insulin_review.pdf. Accessed 6 June 2017.

- 6.Holden SE, Poole CD, Morgan CL, Currie CJ. Evaluation of the incremental cost to the National Health Service of prescribing analogue insulin. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000258. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Type 1 diabetes in adults: diagnosis and type 1 diabetes in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline Published: 26 August 2015. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng17/resources/type-1-diabetes-in-adults-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-1837276469701NICE. Accessed 2 June 2017.

- 8.Ratner RE, Hirsch IB, Neifing JL, Garg SK, Mecca TE, Wilson CA. Less hypoglycemia with insulin glargine in intensive insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes. U.S. Study Group of Insulin Glargine in Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(5):639–643. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.5.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raskin P, Klaff L, Bergenstal R, Halle JP, Donley D, Mecca T. A 16-week comparison of the novel insulin analog insulin glargine (HOE 901) and NPH human insulin used with insulin lispro in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(11):1666–1671. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.11.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herwig J, Scholl-Schilling G, Bohles H. Glycaemic control and hypoglycaemia in children, adolescents and young adults with unstable type 1 diabetes mellitus treated with insulin glargine or intermediate-acting insulin. Journal of pediatric endocrinology & metabolism: JPEM. 2007;20(4):517–525. doi: 10.1515/JPEM.2007.20.4.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiber SA, Russmann A. Long-term efficacy of insulin glargine therapy with an educational programme in type 1 diabetes patients in clinical practice. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(12):3131–3136. doi: 10.1185/030079907X242827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salemyr J, Bang P, Ortqvist E. Lower HbA1c after 1 year, in children with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin glargine vs. NPH insulin from diagnosis: a retrospective study. Pediatric Diabetes. 2011;12(5):501–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2010.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohlfing CL, Wiedmeyer H-M, Little RR, England JD, Tennill A, Goldstein DE. Defining the relationship between plasma glucose and HbA1c: analysis of glucose profiles and HbA1c in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(2):275–278. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marra LP, Araújo VE, Silva TBC, Diniz LM, Guerra Junior AA, Acurcio FA, et al. Clinical effectiveness and safety of analog glargine in type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2016;7(2):241–258. doi: 10.1007/s13300-016-0166-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marra LP, Araújo VE, Oliveria GCC, Diniz LM, Guerra Júnior AA, de Assis Acurcio F, et al. The clinical effectiveness of insulin glargine in patients with type 1 diabetes in Brazil: findings and implications. J Comp Eff Res. 2017;6(6):519–527. doi: 10.2217/cer-2016-0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46(12):1569–1585. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidl EMF, da Costa Zannon CML. Quality of life and health: conceptual and methodological issues. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2004;20(2):580–588. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2004000200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguiar CCT, Fernandes AP, Carvalho AF, Montenegro-Junior RM. Instrumentos de avaliação de qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde no diabetes melito. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol [Internet] 2008;52(6):931–939. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302008000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.da Mata AR, Alvares J, Diniz LM, da Silva MR, Alvernaz dos Santos BR, Guerra Junior AA, et al. Quality of life of patients with diabetes mellitus types 1 and 2 from a referral health centre in Minas gerais, Brazil. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2016;9(5):739–746. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2016.1152180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rwegerera GMMT, Gaenamong M, Oyewo TA, Gollakota S, Rivera YP, Masaka A, Godman B, Shimwela M, Habte D. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among patients with diabetes mellitus in Botswana. Alex J Med. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machado-Alba JE, Medina-Morales DA, Echeverri-Cataño LF. Evaluation of the quality of life of patients with diabetes mellitus treated with conventional or analogue insulins. Diabetes Res ClinPract. 2016;116:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DAFNE Study Group Training in flexible, intensive insulin management to enable dietary freedom in people with type 1 diabetes: dose adjustment for normal eating (DAFNE) randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325(7367):746. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7367.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plank J, Siebenhofer A, Berghold A, Jeitler K, Horvath K, Mrak P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of short-acting insulin analogues in patients with diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(12):1337–1344. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.12.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vardi M, Jacobson E, Nini A, Bitterman H. Intermediate acting versus long acting insulin for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16(3):CD006297. 10.1002/14651858.CD006297.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Singh SR, Ahmad F, Lal A, Yu C, Bai Z, Bennett H. Efficacy and safety of insulin analogues for the management of diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2009;180(4):385–397. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;21(339):b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyzes. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 10 July 2016.

- 28.Higgins JPT, Green S. (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed 3 July 2016.

- 29.Bradley C, Lewis KS. Measures of psychological well-being and treatment satisfaction developed from the responses of people with tablet-treated diabetes. Diabet Med [Internet]. 1990; 7(5):445–51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2142043. Accessed 20 June 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Bradley C. The well-being questionnaire. In: Bradley C, editor. Handbook of psychology and diabetes: a guide to psychological measurement in diabetes research and practice. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 89–109. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradley C. The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ) In: Bradley C, editor. Handbook of psychology and diabetes. 2. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1996. pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mannucci E, Ricca V, Bardini G, Rotella CM. Well-being enquiry for diabetics: a new measure of diabetes-related quality of life. Diab Nutr Metab. 1996;9:89e102. [Google Scholar]

- 33.The DCCT Research Group Reliability and validity of a diabetes quality-of-life measure for the diabetes control and complications trial (DCCT) Diabetes Care. 1988;11(9):725–732. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.9.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradley C, Todd C, Gorton T, Symonds E, Martin A, Plowright R. The development of an individualized questionnaire measure of perceived impact of diabetes on quality of life: the ADDQoL. Qual Life Res [Internet]. 1999; 8(1-2):79–91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10457741. Accessed 6 June 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Päivärinta M, Tapanainen P, Veijola R. Basal insulin switch from NPH to glargine in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9(3 Pt 2):83–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2007.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gallen IW, Carter C. Prospective audit of the introduction of insulin glargine (lantus) into clinical practice in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3352–3353. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.12.3352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manini R, Forlani G, Moscatiello S, Zannoni C, Marzocchi R, Marchesini G. Insulin glargine improves glycemic control and health-related quality of life in type 1 diabetes. NutrMetabCardiovasc Dis. 2007;17(7):493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dixon B, Peter Chase H, Burdick J, Fiallo-Scharer R, Walravens P, Klingensmith G, et al. Use of insulin glargine in children under age 6 with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2005;6(3):150–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2005.00115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolli GB, Songini M, Trovati M, Del Prato S, Ghirlanda G, Cordera R, et al. Lower fasting blood glucose, glucose variability and nocturnal hypoglycaemia with glargine vs. NPH basal insulin in subjects with Type 1 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19(8):571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Witthaus E, Stewart J, Bradley C. Treatment satisfaction and psychological well-being with insulin glargine compared with NPH in patients with Type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2001;18(8):619–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ashwell SG, Bradley C, Stephens JW, Witthaus E, Home PD. Treatment satisfaction and quality of life with insulin glargine plus insulin lispro compared with NPH insulin plus unmodified human insulin in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(6):1112–1117. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polonsky W, Traylor L, Gao L, Wei W, Ameer B, Stuhr A, et al. Improved treatment satisfaction in patients with type 1 diabetes treated with insulin glargine 100 U/mL versus neutral protamine Hagedorn insulin: an exploration of key predictors from two randomized controlled trials. J Diabetes Complicat. 2016;31(3):562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson DF. Understanding financial conflicts of interest. N Engl J Med [Internet] 1993;329(8):573–576. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199308193290812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, Schroll JB, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet] 2017;2:33. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA [Internet]. 2003; 289(4):454–65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12533125. Accessed 2 June 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the papers that were included in the review are cited and can be sourced by other researchers and assessed using similar methodologies.