Abstract

The aim of this paper is to present a new framework to design and run a responsive and resilient health system. It can be used by both private and public, profit and non-profit organizations in order to translate strategic goals of an organization into desirable and intended best practice, and results. This includes the health sector. The framework is based on the four pillars of leadership, ethics, governance and systems, hence called LEGS framework. It can complement the six World Health Organization building blocks that guide inputs to help a health system achieve the intended goals. Despite all the strengths of the World Health Organization building blocks for health systems strengthening, it is important to highlight a few challenges: Ethics is assumed but is not explicitly stated as part of any building block. Furthermore, the World Health Organization framework lacks the flexibility to accommodate other important factors which may differ in various settings and contexts. Hence, the World Health Organization building blocks are either difficult to apply or insufficient in certain contexts, especially in countries with rampant corruption, weak rule of law and systems. This paper explores areas to strengthen the existing framework so as to achieve the intended results efficiently in different contexts. The authors propose LEGS (Leadership, Ethics, Governance and Systems Framework). This framework is very flexible, simple to use, easy to remember, accommodates the existing six WHO building blocks and can better guide different health systems and actors to achieve intended goals by taking into consideration the contextual factors like deficits in moral capital, rule of law or socioeconomic determinants of health.

Background

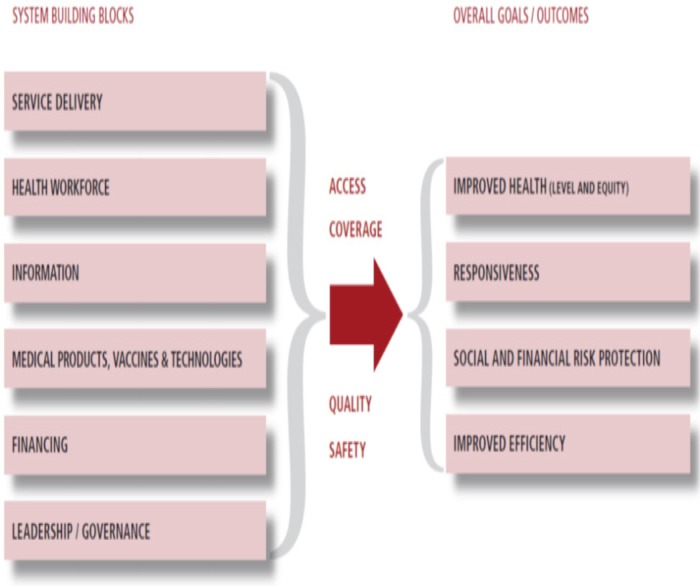

A health system consists of all processes, expertise, structures, organizations, people and actions whose primary purpose is to promote, improve, restore or maintain health.1 The 2000 World Health Report defined overall health system goals as: good health, responsiveness to the expectations of the population and fairness of financial contribution2. This means “improving health and health equity, in ways that are responsive and financially fair, making the most efficient use of available resources3.” An important intermediate goal is access to and coverage for effective health interventions with sufficient quality and safety1. Therefore, a health system's performance should be judged by its efficiency, cost effectiveness, equity and quality. Though health indicators have improved towards the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)4, World Health Organization (WHO)'s statement still holds true, that “public dissatisfaction with the health services is widespread, with accounts of errors, delays, hostility on the part of health workers, and denial of care or exposure to calamitous financial risks by insurers and governments, on a grand scale2.”

WHO established a framework of guiding pillars to deliver health care in the global context. WHO building blocks for strengthening health systems are (i) service delivery, (ii) health workforce, (iii) health information systems, (iv) access to essential medicines, (v) financing, and (vi) leadership/governance (stewardship)1. WHO considers finances, leadership/governance and health workforce as key inputs1.

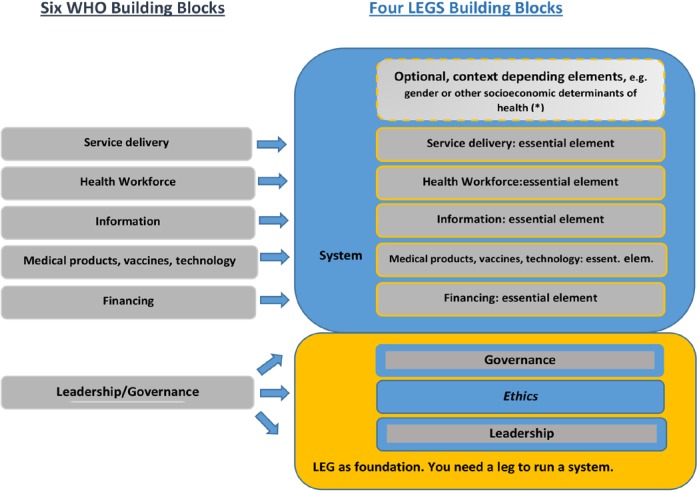

“Leadership and governance involves ensuring strategic policy frameworks exist and are combined with effective oversight, coalition building, regulation, attention to system-design and accountability3,5”. In countries with weak states/institutions or with low moral capital this approach could be insufficient6. The SDGs recognize the importance of strong institutions and absence of corruption as pre-requisites for sustainable development7. To fill the gap, this new framework was developed. LEGS framework, as conceptualized by Joseph Mathews Mfutso-Bengo in 2016, emerged from a desk literature review with thematic analysis that assessed the key determinants influencing system failure in an organization or country to deliver intended results6. As result of the analysis, the themes of lack of leadership, ethical engagement, governance and weak systems were identified as the most frequent causes for institutional inability to achieve its strategic goals6. Hence, the authors propose Leadership, Ethics, Governance and Systems (LEGS) as key determinants that are enabling factors for translating health policy and evidence into the best professional practices. LEGS is a useful tool for the development and implementation of strategic plans. Due to its responsiveness and flexibility, the LEGS framework is suitable not only for the health sector but also for other sectors and contexts. The article shows how LEGS is applied to the WHO context.

The LEGS building blocks and WHO building blocks for health systems strengthening: Similarities, differences and complementary nature

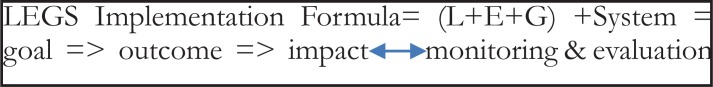

The four building blocks of system design, policy-formulation and implementation according to the presented framework are Leadership, Ethics, Governance and Systems. The authors maintained the WHO terminology of “building blocks” to describe its four integrated pillars. These four “LEGS” are necessary and essential building blocks to be considered for achieving intended goals, desired impact and results in implementation of health systems and policies.

In the LEGS framework, “system” is one of the four building blocks for health policy design and implementation. According to WHO as show in Figure 1, the system has six building blocks, whereas according to the LEGS framework, the “system” is a building block which has elements determined by the intended goals and outcomes of a particular organization and context. The following WHO building blocks of service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, access to essential medicines and financing would be elements in the LEGS building block “system”.

Figure 1.

The WHO Health System Framework (Source: World Health Organization. Everybody's business: Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. 2007 p. 3)

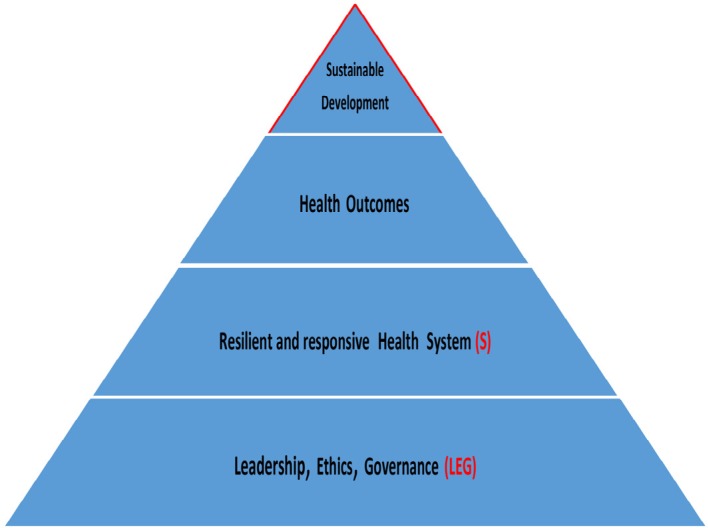

In the LEGS framework, leadership, ethics, and governance (LEG) are foundations for building a resilient system. One needs a LEG to run a system. LEGS shows that one needs more than a system to translate policy into practice, and health rights into human health.

Foundations for resilient health systems

LEGS is a complementary tool for strengthening health systems to achieve the aim of universal access to health3, especially in countries with weak governance and rule of law. LEGS framework complements WHO building blocks by mainly highlighting ethics as an indispensable building block for a responsive and resilient health system8. WHO describes its building blocks as a useful way of clarifying essential functions and accepts that the challenges faced by countries require a more integrated structure that recognizes the inter-dependence of each part of the health system3.

Justification for LEGS building blocks as a new complementary framework

The LEG

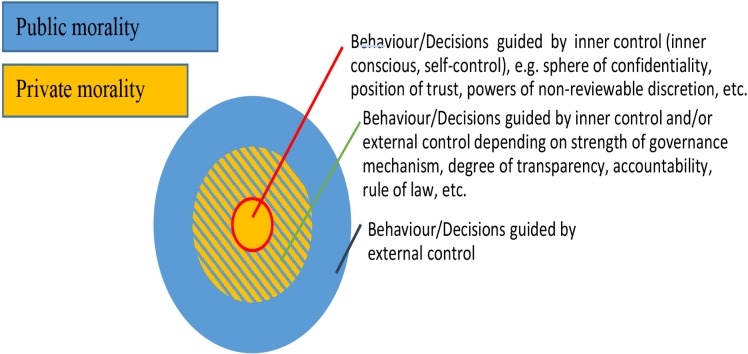

WHO building blocks for strengthening health systems lack an explicit ethics component. While governance is built around issues of prioritizing, monitoring performance, transparency, accountability and external social control, ethics leads to higher internal social control. Ethics includes an investment in the promotion and practice of virtues and moral reasoning skills. Ethical behavior, discretion and judgment at various levels (e.g., procurement, clinical work, human resource, systems design and research) cannot completely be influenced by external social control. However, ethical decision-making ought to be influenced by four ethical principles namely: beneficence, non-maleficence, respect and justice9 and the authors propose it should be value and evidence based. Ethics is moral capital in action. Moral capital includes the combination of virtues, appropriate for a particular profession or organization6. The term moral capital is defined by the authors as: a combination of appropriate knowledge, right attitude (combination of relevant virtues) and appropriate skills suitable for a particular profession, organization and context. Ethics requires forming and reinforcing moral capital through coaching, value and evidence based education/awareness and decision-making. It also requires ethical engagement consisting of ethical procedures and means (e.g. no undue influence or corruption) and ethical use of bureaucracy, balancing the need for fairness, inclusiveness and efficiency without abusing procedures for wrong motives (e.g. delay of bureaucratic process for reasons of corruption or power politics).

According to the Bribe Payers Survey, the pharmaceutical and health sector scored 6.1 on a 10-point scale on the perception of likelihood of bribes being paid10. (It is based on business people's views on likelihood of bribes being paid by companies, with bribery being perceived to be common across all 19 sectors with no sector scoring above 7.1 on a scale from 1 to 10 with 1 meaning less likely and 10 meaning more likely.) This demonstrates the need for honesty and integrity in this sector. The Corruption Perception Index states that 68% of countries have serious corruption problems, no country being corruption free11. According to Ernst &Young 2016 Fraud Survey, 21% of participants in developed markets reported corruption and bribery as widespread and 51% in emerging markets12. 42% of chief financial officers would justify unethical practices to meet financial targets12. 7% of finance members would be willing to misstate figures12. The authors argue that corruption and unethical reporting reduce efficient service delivery and can lead to distorted policy and system design. Profit-oriented companies cite corruption as the top hindering factor for foreign direct investment13. Hence, the authors conclude that the general high levels of corruption in a country or organization render health spending less equitable, effective and efficient. This is the reason why ethics/moral capital matters.

Transparency International described the pharmaceutical industry as vulnerable to corruption14, which is interlinked with access to medicines and financing. WHO acknowledges that inefficient use of funds could be due to corruption1. It is insufficient to effect change when ethics is treated as incidental or implied because one knows that unethical behavior like corruption can disorganize, derail, undermine and damage the design15 or operation of any health system. According to the authors ethics being an individual and collective/organizational issue should not be confined solely to the “health workforce” and “finance” as building blocks since it is highly relevant for all other WHO building blocks. How can one expect WHO building blocks to produce health equity and access to essential medicines as an ethical outcome, when the system does not explicitly have Ethics/fostering of the right attitudes as input on all levels? An ethics component that constitutes internal self-control matters more where external controls are weak, where the rule of law is still developing and where drug theft, fraud and medical malpractice are high. Though it is difficult to quantify16, actual levels of corruption, moral risks for corruption and fraud exist worldwide17. Even societies with high moral capital require a continuous effort to maintain it by moral capital investments in character development, right attitude and fostering an environment of integrity. Hence, Ethics is an indispensable building block for strengthening the health system globally.

The authors propose that governance has to be complemented with ethics and leadership for it to be responsible. An organization can appear to be transparent and accountable with procurement and tendering policies - yet the process can be staged. Selective justice is another example of unethical governance, be it at private, institutional or state levels. Lobbyism can be legal and transparent, but its impact can be unethical or ethical. Persson et al. argue that anti-corruption reforms concentrating merely on transparency and punishment fail in countries with systemic corruption because non-corrupt principals/monitors cannot always be presumed18. Hence, ethical and evidence based policy- and decision-making and system design are required at all levels of process management.

LEGS has unpacked the WHO building block of Leadership/governance into three separate but integrated building blocks, namely: leadership, ethics and governance. According to the Hersey theory of situational leadership, styles of leadership must be responsible and responsive to the situational needs19. This means appropriate leadership-styles differ, not only with followers, the person or group and culture that is being influenced, but they also depend on the task, job or function, and vision that needs to be accomplished. Situational leadership should be complemented by informed, ethical and transformational leadership20, which is responsive to the contextual needs.

Governance in the LEGS framework places an emphasis on monitoring, controlling, transparency and accountability of all system components and leadership at all levels. Governance, leadership and ethics are structured as interlinked building blocks providing checks and balances.

The lack of any of the three building blocks of the LEG cannot be compensated and in turn destroys the other two blocks. Deficits in one of them cannot fully be compensated by the others6.

According to LEGS, to build an ethical and resilient system, one needs to have a preceding foundation (LEG) based on these three closely interconnected and integrated building blocks to integrate the components/WHO building blocks of the system.

The System

A “LEG” without a system cannot have an impact or achieve its intended outcome because a system is a means to achieve a goal. Therefore, the three preceding buildings blocks of the LEGS framework are proceeded by a building block “system” which contains elements identified through ethical and evidence based engagement responsive to a context. Countries differ in levels of economic development, social conditions, political values, disease patterns, disease burdens and institutional arrangements5. In some countries, the civil service is reliable, disciplined and professional; in others, it is corrupt and ineffective21. Some countries have good governance; others have experienced years of corruption, political terror, instability and state capture. These factors affect how the problems in health systems are defined, and the kinds of solutions and resolutions that are most likely to work. In some countries, interventions on socioeconomic determinants of health or public health interventions translate into a higher impact for the realization of health rights22. Since existing deficits vary, interventions have a different impact. LEGS framework building blocks are responsive to contextual needs and demands. The authors' goal is to highlight this contextual dependency of any health system1. WHO underlined the need for inter-sectorial intervention2,23. Again this requires coordination and co-operation based on good leadership, ethical engagement and governance.

LEGS building blocks are ranked based on what comes first and what comes last.

Discussion and implementation of LEGS framework in health systems strengthening

LEGS framework is easy to comprehend, easy to use, and is responsive to the cultural and social context. The authors agree with WHO that the WHO building blocks form a core structural framework in a system and that each block is essential. The LEGS framework is flexible enough to accommodate all of the blocks, whereas the WHO building blocks framework is not flexible enough to accommodate additional system components. The WHO building blocks consider governance and financing as prerequisite and input.

LEGS requires that one needs a LEG to run a system; before one builds or runs a system, one needs to ensure that there is strong leadership, ethics and good governance as the three necessary, interlinked foundational building blocks for building a resilient health system (e.g. financing without ethics opens opportunities for inequity). The actual implementation of any health program requires a better understanding of the disposing factors, enabling factors and the reinforcing factors. LEGS framework wishes to utilize “the precede and proceed model24” as a tool for policy implementation and behavior change in an organization or nation. LEGS' disposing factors are: right attitude and ethical engagement, followed by enabling factors which ensure that the system has all the necessary capacity to achieve the intended results. LEGS framework is flexible enough to include additional enabling factors and social determinants in the system(s) components such as gender, poverty, education etc., depending on context. Reinforcing factors are leadership, governance, fair reward and sanctioning systems that do not destroy but foster right attitude or intrinsic motivation as driving, monitoring and controlling factors that ensure that the system remains in its clearly set direction.

This framework needs to be validated through an efficacy, acceptability and feasibility study.

Conclusion

The LEGS framework can complement the existing six WHO building blocks. It may be appropriate, especially for developing countries which have governance or ethics challenges. Leadership, ethical engagement and governance are integral building blocks to run an efficient and ethical resilient system.

One needs LEGS to implement health policy to achieve intended results and health rights. The goal of WHO to achieve health equity can be achieved if ethics is added as an input and visibly mainstreamed in all WHO building blocks. Such ethical engagement should be at all levels (e.g., procurement, clinical work, human resource, systems design and research) and is influenced by four ethical principles namely: beneficence, non-maleficence, respect and justice. Moral capital investment and formation need mainstreaming in the education sector to create a suitable workforce for administration, health care and governance.

The authors conclude that one needs LEG to run any resilient and responsive system and recommend that the WHO building block leadership/governance should be unpacked into leadership, governance and ethics. One could also add a seventh building block of ethics as one of WHO building blocks for health systems strengthening.

Figure 2.

WHO building blocks and LEGS building blocks: similarities, differences, complementary nature

Figure 3.

The Leadership-Ethics-Governance-System Framework (LEGS)

Figure 4.

Ethics as indispensable building block

References

- 1.World Health Organization, author. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [10 December 2016]. Available at: www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/WHO_MBHSS_2010_full_web.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, author. The World Health Report 2000 Improving health systems. 2000. [10 December 2016]. Available at: http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf.

- 3.World Health Organization, author. Everybody's business - strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO's framework for action. [27 April 2016]. Available at: www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf?ua=1.

- 4.World Health Organization, author. World Health Statistics 2015. New York: WHO; 2015. [10 December 2016]. p. 124. Available at: www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith PC, Anell A, Busse R, Luca C, Healy J, Lindahl AK, et al. Leadership and governance in seven developed health systems. Health Policy. 2012;106(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mfutso-Bengo JM. Bioethics as moral capital: Mind-building for sustainable development and professionalism. Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishers; 2016. pp. 68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 7.IAEG, author. Final list of proposed Sustainable Development Goals Indicators Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators (E/CN.3/2016/2/Rev.1): Annex IV SDG 16.5. [10 December 2016]. Available at: http://.unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/indicators-list/

- 8.See Ruger JP. Ethics in American health 2: an ethical framework for health system reform. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1756–1763. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford; 2001. pp. 57–225. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Transparency International, author. “Bribe Payers Index 2011.”. 2011. [3 March 2016]. p. 14. Available at: www.transparency.org/bpi2011.

- 11.Transparency International, author. Corruption Perception Index. 2015. [1 December 2016]. Available at: www.transparency.org/cpi2015.

- 12.Ernst and Young, author. Corporate misconduct - individual consequences: Global enforcement focuses the spotlight on executive integrity 14th Global Fraud Survey. EYGM; 2016. [10 December 2016]. Available at: www.ey.com/gl/en/services/assurance/fraud-investigation-dispute/services/ey-global-fraud-survey-2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asiedu E. Foreign direct investment in Africa: The role of natural resources, market size, government policy, institutions and political instability. World Econ. 2006;29:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Transparency International, author. Corruption in the Pharmaceutical Sector: Diagnosing the challenges. 2016. Jun, [2 November 2016]. Available at: http://www.transparency.org.uk/publications/corruption-in-the-pharmaceutical-sector/

- 15.Hellman J, Kaufmann D. Confronting the challenge of state capture in transition economies. [10 December 2016];Fin Dev. 2001 38(3) Available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2001/09/hellman.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck L. Anticorruption in Public Procurement - A Qualitative Research Design. University of Passau; 2012. [30 November 2016]. Dissertation, II.1. Available at: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-uni-passau/files/169/Beck_Lotte.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellmann JS, Gereint J, Daniel Kaufmann D. Seize the state, seize the day: State capture, corruption, and influence in transition economies. Washington: 2000. [10 December 2016]. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 2444. Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/wbi/governance. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Persson A, Rothstein B, Teorell J. Why anticorruption reforms fail—systemic corruption as a collective action problem. Governance. 2013;26(3):449–471. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hersey P, Blanchard KH. Life cycle theory of leadership. Train Dev J. 1969;23(5):26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC, Van Engen ML. Transformational, transactional and laissez-faire leadership styles: a meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(4):569–559. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Transparency International, author. Corruption Perception Index, CPI. 2014. [1 March 2015]. www.transparency.org/research/cpi/overview.

- 22.Frieden TR. A Framework for Public Health Action: The Health Impact Pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(4):590–595. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishai DM, Cohen R, Alfonso YN, Adam T, Kururilla S, Schweitzer J. Factors contributing to maternal and child mortality reductions in 146 low- and middle-income countries between 1990 and 2010. [14 December 2016];PLoS ONE. 2016 11(1):e0144908. doi: 10.1371/journal/pone.0144908. Available at: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0144908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crosby R, Noar SM. What is a planning model? An introduction to PRECEDE-PROCEED. J of Public Health Dent. 2011;71(1):7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2011.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]