Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

SOCRATES, comparing ticagrelor with aspirin in patients with acute cerebral ischemia, found a nonsignificant 11% relative risk reduction for stroke, myocardial infarction or death (P=0.07). Aspirin intake before randomization could enhance the effect of ticagrelor by conferring dual antiplatelet effect during a high-risk period for subsequent stroke. Therefore, we explored the efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus aspirin in the patients who received any aspirin the week prior to randomization.

METHODS

A pre-specified subgroup analysis in SOCRATES (N=13199), randomizing patients with acute ischemic stroke (NIHSS ≤5) or TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4) to 90-day treatment with ticagrelor or aspirin. Patients in the prior-aspirin group had received any aspirin within the week before randomization. Primary endpoint was time to stroke, myocardial infarction, or death. Safety endpoint was PLATO major bleeding.

RESULTS

The 4232 patients in the prior-aspirin group were older, had more vascular risk factors and vascular disease than the other patients. In the prior-aspirin group, the primary endpoint occurred in 138/2130 (6.5%) of patients on ticagrelor and in 177/2102 (8.3%) on aspirin (HR 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61–0.95, P=0.02); in patients with no prior aspirin usage an event occurred in 304/4459 (6.9%) and 320/4508 (7.1%) on ticagrelor and aspirin, respectively (HR 0.96; 95% CI, 0.82–1.12, P=0.59). The treatment-by-prior-aspirin interaction was not statistically significant (P=0.10). In the prior-aspirin group, major bleeding occurred in 0.7% and 0.4% of patients on ticagrelor and aspirin, respectively (HR 1.58; 95% CI 0.68–3.65, P=0.28).

CONCLUSION

In this secondary analysis from SOCRATES fewer primary endpoints occurred on ticagrelor treatment than on aspirin in patients receiving aspirin prior to randomization, but there was no significant treatment-by-prior-aspirin interaction. A new study will investigate the benefit-risk of combining ticagrelor and aspirin in patients with acute cerebral ischemia (NCT03354429).

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ Unique identifier: NCT01994720.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack, ticagrelor, aspirin, antiplatelet

Subject terms: stroke, ischemic stroke

INTRODUCTION

Recent clinical trial and registry data show that patients with acute cerebral ischemic events are at a high and immediate risk of experiencing potentially more severe and disabling recurrent ischemic events, especially strokes.1–3 Aspirin reduces the risk of subsequent stroke and death following acute cerebral ischemia4,5 and is recommended for secondary prevention.6 In the CHANCE (Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events) trial, dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel (P2Y12 receptor antagonist) and aspirin significantly reduced the risk for stroke versus aspirin alone in a Chinese population with acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA).1 However, a large unmet medical need persists for novel, effective treatment options to improve outcomes among patients with acute minor ischemic stroke and TIA, particularly given the variability in clopidogrel response.7

The SOCRATES (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated with Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes) trial investigated whether ticagrelor, a reversibly binding, direct-acting oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist and inhibitor of type 1 equilibrative nucleoside transporter (ENT1),8,9 was superior to aspirin for prevention of the composite of stroke, myocardial infarction and death, when initiated within 24 hours after symptom onset in patients with acute cerebral ischemia.10 A non-significant 11% relative risk reduction of the primary endpoint was found in SOCRATES.3

Addition of ticagrelor for patients who received aspirin before randomization in SOCRATES may confer the effect of dual antiplatelet therapy, since aspirin’s antiplatelet effect persists during the first week when the risk of new stroke events is highest. This pre-specified analysis of SOCRATES explored ticagrelor safety and efficacy in patients receiving aspirin prior to randomization.

METHODS

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be obtained in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy available at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure.

SOCRATES design and primary results have been presented previously.3,10 The trial was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee at each site. Patients provided written informed consent before any study-specific procedures were performed.

Patients (n=13199) with a non-cardioembolic, non-severe ischemic stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale Score [NIHSS] ≤5) or high-risk TIA (ABCD2 score ≥4 or symptomatic ipsilateral stenosis of an extra or intracranial artery) were randomized (interactive web-based randomization system) within 24 h of symptom onset to double-blinded treatment with ticagrelor 180 mg loading dose on day 1 followed by 90 mg twice daily for days 2–90 or aspirin 300 mg on day 1 followed by 100 mg daily for days 2–90.

Concomitant medication information, particularly aspirin use, was collected; including start and stop date for medications initiated or stopped during the month prior to randomization. The prior-aspirin subgroup were patients receiving any aspirin within 7 days before randomization. Atherosclerosis was assessed by Atherosclerosis, Small-Vessel Disease, Cardiac Pathology, Other Causes, Dissection (ASCOD) phenotyping to assign stroke cause and grade; A0 = no atherosclerotic disease; A1 (likely causal) = ≥50% ipsilateral stenosis of extracranial or intracranial arteries or a mobile thrombus in the aortic arch; A2 (causal relationship possible but uncertain) = <50% stenosis of extracranial or intracranial artery or an aortic arch plaque of >4 mm in thickness without mobile thrombus; A3 (unlikely causal) = plaque without stenosis or a stenosis in an artery contralateral to the cerebral infarct or a concomitant coronary or peripheral arterial disease; A9 = insufficient information to grade atherosclerosis (no assessment of either intracranial arteries or extracranial arteries).11 The prior-aspirin group was also analyzed by aspirin dose (>150 mg versus ≤150 mg), to explore any dose-related impact on efficacy of prior aspirin use, and by start day of aspirin treatment as either: 1) starting the day before or the same day as randomization, representing patients receiving an ‘acute treatment’ with aspirin after onset of symptoms but before randomization e.g. as part of pre-hospital emergency care or at the emergency ward, or 2) starting earlier than the day before randomization considered as a proxy for ‘chronic treatment’, i.e. aspirin treatment was ongoing at the time of the index event, since the start date was out of the possible time-window of 24 hours between the start of the index event and randomization.

The primary endpoint for SOCRATES was the time from randomization to first occurrence of any event from the composite of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), myocardial infarction, or death at 90 days; each of these components was based on standard definitions.10 An exploratory analysis of the primary endpoint at 7 days was performed; at this time point, due to platelet lifespan and renewal, any effect of aspirin intake before randomization is expected to have disappeared and a sufficient number of events was expected to have occurred to make it possible to detect an early treatment effect. The secondary efficacy endpoint was ischemic stroke. The primary safety endpoint was PLATO major bleeding. An independent Clinical Event adjudication Committee (CEC), blinded to study treatment, adjudicated all components of the efficacy endpoint and classified all bleed events, not considered as minimal by the investigator, according to the PLATO bleeding definition.10,12

Statistical methods

The prior-aspirin subgroup analysis was pre-specified and exploratory. Efficacy analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle using adjudicated events and including all randomized patients. Safety analyses of bleeding events were performed for patients receiving at least one dose of randomized treatment. Time from randomization to the first occurrence of any event for a given endpoint was analyzed by the Cox proportional hazards model with treatment as the only factor. Interaction between treatment assignment and prior-aspirin indicator was evaluated by including terms for treatment, prior-aspirin indicator, and treatment-by-prior-aspirin indicator interaction in the Cox model. Interaction terms with a P value <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. This conservative approach of assessing interaction in subgroup analyses (rather than using P<0.10) was considered appropriate, given that the primary outcome of the SOCRATES trial was not statistically significant (P=0.07).3

Baseline characteristics were compared for patients in the prior-aspirin sub group and those with no prior aspirin usage. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and continuous variables as median with interquartile range or mean with standard deviation (SD). χ2 test and t test were performed for comparison of categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics were balanced among ticagrelor and aspirin groups.3 Criteria for prior-aspirin usage was met in 4232 patients (ticagrelor: 2130; aspirin: 2102), while 8967 patients (ticagrelor: 4459; aspirin: 4508) did not use aspirin in the 7 days prior to randomization (Table 1). There were multiple differences in baseline factors among prior- and no-prior aspirin subgroups, mainly driven by the ‘chronic treatment’ prior-aspirin group (Table 1). There were some patients who had received clopidogrel prior to randomization (Table 1); a sensitivity analysis excluding these patients did not impact on the overall results of this study. The distribution of patients with ipsilateral atherosclerotic stenosis (A1–A2) was similar in the prior-aspirin and no prior-aspirin subgroups. However, patients with ‘chronic treatment’ in the prior-aspirin subgroup had higher atherosclerotic burden overall (A1–A3) and higher presence of ipsilateral stenosis versus patients with ‘acute treatment’ (Table 2).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Participants by Prior Aspirin

| Characteristics | Prior aspirin (n=4232) | Prior aspirin ‘Chronic treatment’ (n=1731) | Prior aspirin ‘Acute treatment’ (n=2501) | No prior aspirin (n=8967) | P Value (Prior aspirin vs no prior aspirin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Age (years) – mean (SD) | 67.1 (11.5) | 70.4 (10.4) | 64.8 (11.6) | 65.3 (11.2) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Female sex – n (%) | 1748 (41.3) | 731 (42.2) | 1017 (40.7) | 3735 (41.7) | 0.70 |

|

| |||||

| Race – n (%) | |||||

| Caucasian | 3008 (71.1) | 1468 (84.8) | 1540 (61.6) | 5776 (64.4) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 126 (3.0) | 37 (2.1) | 89 (3.6) | 113 (1.3) | |

| Asian | 1039 (24.6) | 197 (11.4) | 842 (33.7) | 2867 (32.0) | |

| Other | 59 (1.4) | 29 (1.7) | 30 (1.2) | 211 (2.4) | |

|

| |||||

| Region – n (%) | |||||

| Asia and Australia | 1059 (25.0) | 199 (11.5) | 860 (34.4) | 2912 (32.5) | <0.0001 |

| Europe | 2415 (57.1) | 1197 (69.2) | 1218 (48.7) | 5126 (57.2) | |

| North America | 613 (14.5) | 241 (13.9) | 372 (14.9) | 441 (4.9) | |

| Central and South America | 145 (3.4) | 94 (5.4) | 51 (2.0) | 488 (5.4) | |

|

| |||||

| Systolic BP (mmHg), median (IQR) | 150 (135–165) | 150 (135–165) | 150 (134–166) | 150 (138–165) | 0.09 |

|

| |||||

| Diastolic BP (mmHg), median (IQR) | 80 (74–90) | 80 (73–90) | 82 (74–91) | 85 (80–93) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 26.3 (23.9–29.7) | 27.1 (24.2–30.5) | 26.0 (23.6–29.1) | 26.0 (23.4–29.1) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| History of – n (%) | |||||

| Hypertension | 3196 (75.5) | 1523 (88.0) | 1673 (66.9) | 6534 (72.9) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1170 (27.6) | 616 (35.6) | 554 (22.2) | 2042 (22.8) | <0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 2016 (47.6) | 1061 (61.3) | 955 (38.2) | 3012 (33.6) | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic stroke | 639 (15.1) | 469 (27.1) | 170 (6.8) | 954 (10.6) | <0.0001 |

| TIA | 394 (9.3) | 244 (14.1) | 150 (6.0) | 462 (5.2) | <0.0001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 312 (7.4) | 235 (13.6) | 77 (3.1) | 236 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 510 (12.1) | 375 (21.7) | 135 (5.4) | 634 (7.1) | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 136 (3.2) | 105 (6.1) | 31 (1.2) | 346 (3.9) | 0.06 |

|

| |||||

| Taking clopidogrel before randomization – n (%) | 209 (4.9) | 80 (4.6) | 129 (5.2) | 247 (2.8) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Time to randomization <12 h – n (%) | 1108 (26.2) | 647 (37.4) | 461 (18.4) | 3716 (41.4) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Ischemic stroke as a qualifying event – n (%) | 2893 (68.4) | 1154 (66.7) | 1739 (69.5) | 6774 (75.5) | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Qualifying TIA baseline ABCD2 score ≤5 – n (%)* | 967 (72.2) | 398 (69.0) | 569 (74.7) | 1603 (73.1) | 0.55 |

|

| |||||

| Qualifying ischemic stroke baseline NIHSS ≤3† | 2092 (72.3) | 800 (69.3) | 1292 (74.3) | 4425 (65.3) | <0.0001 |

% calculated based on total TIA patients;

% calculated on total stroke patients

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; IQR, interquartile range; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

Table 2.

ASCOD Atherosclerosis Grade by Prior Aspirin

| Number (%) of Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASCOD atherosclerosis grade | Prior aspirin (n=4232) | Prior aspirin ‘Chronic treatment’ (n=1731) | Prior aspirin ‘Acute treatment’ (n=2501) | No prior aspirin (n=8967) |

| A0 | 1581 (37.4) | 547 (31.6) | 1034 (41.3) | 3374 (37.6) |

| A1 | 384 (9.1) | 152 (8.8) | 232 (9.3) | 736 (8.2) |

| A2 | 635 (15.0) | 302 (17.4) | 333 (13.3) | 1326 (14.8) |

| A3 | 780 (18.4) | 382 (22.1) | 398 (15.9) | 1116 (12.4) |

| A9 | 822 (19.4) | 333 (19.2) | 489 (19.6) | 2372 (26.5) |

| Missing | 30 (0.7) | 15 (0.9) | 15 (0.6) | 43 (0.5) |

A0, no atherosclerotic disease; A1 (likely causal), ≥50% ipsilateral stenosis of extracranial or intracranial arteries or a mobile thrombus in the aortic arch; A2 (causal relationship possible but uncertain), <50% stenosis of extracranial or intracranial artery or an aortic arch plaque of >4 mm in thickness without mobile thrombus; A3 (unlikely causal), plaque without stenosis or a stenosis in an artery contralateral to the cerebral infarct or a concomitant coronary or peripheral arterial disease; A9, insufficient information to grade atherosclerosis (no assessment of either intracranial arteries or extracranial arteries).11

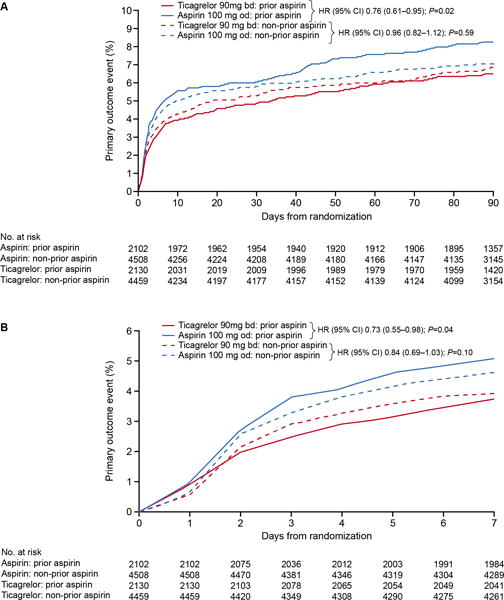

In the prior-aspirin group, a primary endpoint occurred in 138/2130 (KM%: 6.5%) patients randomized to ticagrelor and in 177/2102 (KM%: 8.3%) patients randomized to aspirin (hazard ratio [HR] 0.76; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.61–0.95, P=0.02). For the no prior-aspirin group, 304/4459 (KM%: 6.9%) of patients randomized to ticagrelor and 320/4508 (KM%: 7.1%) of patients randomized to aspirin experienced a primary endpoint (HR 0.96; 95% CI 0.82–1.12, P=0.59) (Table 3, Figure 1a). The treatment-by-prior-aspirin interaction did not reach statistical significance (P=0.10). The stroke component was the major contributor to primary endpoint events. There was a consistent pattern for the effect in patients in the prior-aspirin group randomized to ticagrelor on deaths and MIs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Efficacy Outcome by Prior-Aspirin Subgroup.

| Ticagrelor 90 mg bd (n=6589) | Aspirin 100 mg OD (n=6610) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Efficacy outcome | Prior aspirin* | n | Patients with events (%) | KM%† | n | Patients with events (%) | KM%† | HR (95% CI) | P Value | P value interaction‡ |

|

| ||||||||||

| Composite of stroke/MI/death | Yes | 2130 | 138 (6.5) | 6.5 | 2102 | 177 (8.4) | 8.3 | 0.76 (0.61–0.95) | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| No | 4459 | 304 (6.8) | 6.9 | 4508 | 320 (7.1) | 7.1 | 0.96 (0.82–1.12) | 0.59 | ||

| Prior-aspirin therapy,* by start day | Chronic treatment§ | 890 | 58 (6.5) | 6.6 | 841 | 66 (7.8) | 7.4 | 0.82 (0.58–1.17) | 0.27 | 0.58 |

| Acute treatment| | 1240 | 80 (6.5) | 6.5 | 1261 | 111 (8.8) | 8.8 | 0.72 (0.54–0.97) | 0.03 | ||

| Prior-aspirin therapy,* by dose | Dose >150 mg | 792 | 51 (6.4) | 6.5 | 796 | 64 (8.0) | 8.0 | 0.80 (0.55–1.15) | 0.23 | 0.74 |

| Dose ≤150 mg | 1338 | 87 (6.5) | 6.6 | 1306 | 113 (8.7) | 8.4 | 0.74 (0.56–0.98) | 0.03 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Stroke | Yes | 2130 | 126 (5.9) | 6.0 | 2102 | 154 (7.3) | 7.2 | 0.80 (0.63–1.01) | 0.06 | 0.41 |

| No | 4459 | 264 (5.9) | 6.0 | 4508 | 296 (6.6) | 6.6 | 0.90 (0.76–1.06) | 0.21 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| MI | Yes | 2130 | 8 (0.4) | 0.4 | 2102 | 10 (0.5) | 0.5 | 0.79 (0.31–1.99) | 0.61 | 0.26 |

| No | 4459 | 17 (0.4) | 0.4 | 4508 | 11 (0.2) | 0.3 | 1.57 (0.73–3.35) | 0.25 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Death | Yes | 2130 | 16 (0.8) | 0.8 | 2102 | 25 (1.2) | 1.2 | 0.63 (0.34–1.18) | 0.15 | 0.02 |

| No | 4459 | 52 (1.2) | 1.2 | 4508 | 33 (0.7) | 0.7 | 1.60 (1.03–2.47) | 0.04 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Ischemic stroke | Yes | 2130 | 123 (5.8) | 5.8 | 2102 | 153 (7.3) | 7.1 | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.29 |

| No | 4459 | 262 (5.9) | 5.9 | 4508 | 288 (6.4) | 6.4 | 0.92 (0.78–1.08) | 0.31 | ||

bd, twice daily; MI, myocardial infarction; OD, once daily

Patients in the prior-aspirin subgroup had received aspirin within 7 days before randomization

Kaplan-Meier %; the event rate at 90 days

Interaction between treatment assignment and prior aspirin indicator was evaluated by including terms for treatment, prior-aspirin indicator, and treatment-by-prior-aspirin indicator interaction in the Cox model (P<0.05 was considered statistically significant)

Start of treatment occurring earlier than the day before randomization

Start of treatment occurring the day before or the same day as randomization

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for the primary endpoint (time to stroke, myocardial infarction, or death) in patients randomized to the aspirin or ticagrelor groups with or without taking aspirin prior to randomization: a) full 90-day treatment period; b) censored at 7 days.

bd, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; and od, once daily.

The effect on the secondary efficacy endpoint, ischemic stroke, in patients with prior- aspirin usage randomized to ticagrelor (HR 0.78; 95% CI 0.62–0.99, P=0.04) was consistent with that on the primary endpoint (Table 3).

The primary endpoint censored at day 7 in the prior-aspirin subgroup showed that 80/2130 (3.8%) of patients treated with ticagrelor and 107/2102 (5.1%) treated with aspirin experienced a primary endpoint (HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.55–0.98, P=0.04). In the no prior-aspirin group, a primary endpoint occurred within 7 days in 175/4459 (3.9%) in the ticagrelor group and 209/4508 (4.6%) in the aspirin group (HR 0.84; 95% CI 0.69–1.03, P=0.10) (Figure 1b).

Table 3 shows the impact of timing and dose of prior aspirin on outcome. The HR for the primary endpoint for patients with prior-aspirin usage randomized to ticagrelor versus aspirin was similar in patients receiving an ‘acute treatment’ (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.54–0.97, P=0.03) and patients on ‘chronic treatment’ (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.58–1.17, P=0.27); P-value for interaction was 0.58.

In the prior-aspirin group, major bleeding occurred in 0.7% of patients randomized to ticagrelor and in 0.4% randomized to aspirin (HR 1.58; 95% CI 0.68–3.65, P=0.28), with no increase of life threatening bleedings, including intracranial bleedings (Table 4). The combination of major or minor bleedings in the prior-aspirin group was more common among patients randomized to ticagrelor versus aspirin (HR 1.76; 95% CI 1.09–2.85, P=0.02).

Table 4.

Safety Outcomes by Prior-Aspirin Sub group

| Ticagrelor 90 mg bid (n=6549) | Aspirin 100 mg OD (n=6581) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Safety outcomes* Bleeding according to PLATO bleeding definition |

Prior aspirin | n | Patients with events (%) | KM%† | n | Patients with events (%) | KM%† | HR (95% CI) | P Value | P Value interaction‡ |

|

| ||||||||||

| Major | Yes | 2107 | 14 (0.7) | 0.7 | 2083 | 9 (0.4) | 0.4 | 1.58 (0.68–3.65) | 0.28 | 0.07 |

| No | 4442 | 17 (0.4) | 0.4 | 4498 | 29 (0.6) | 0.7 | 0.60 (0.33–1.09) | 0.09 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Major, fatal/life-threatening | Yes | 2107 | 7 (0.3) | 2083 | 7 (0.3) | |||||

| No | 4442 | 15 (0.3) | 0.4 | 4498 | 20 (0.4) | 0.5 | 0.77 (0.39–1.50) | 0.44 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Fatal bleeding | Yes | 2107 | 1 (0) | 2083 | 1 (0) | |||||

| No | 4442 | 8 (0.2) | 4498 | 3 (0.1) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Intracranial hemorrhage | Yes | 2107 | 4 (0.2) | 2083 | 4 (0.2) | |||||

| No | 4442 | 8 (0.2) | 0.2 | 4498 | 14 (0.3) | 0.3 | 0.58 (0.25–1.39) | 0.23 | ||

|

| ||||||||||

| Major, other | Yes | 2107 | 7 (0.3) | 2083 | 2 (0.1) | |||||

| No | 4442 | 2 (0) | 4498 | 9 (0.2) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Major or minor | Yes | 2107 | 45 (2.1) | 2.3 | 2083 | 26 (1.2) | 1.2 | 1.76 (1.09–2.85) | 0.02 | 0.14 |

| No | 4442 | 61 (1.4) | 1.4 | 4498 | 56 (1.2) | 1.3 | 1.12 (0.78–1.60) | 0.55 | ||

bid, twice daily; KM, Kaplan-Meier; OD, once daily

Safety analysis set

Kaplan-Meier %; the event rate at 90 days

Kaplan-Meier %, hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals were not calculated if the total number of events was <15

DISCUSSION

In this pre-specified exploratory analysis of SOCRATES, there was a trend towards a better treatment effect of ticagrelor over aspirin in patients who received aspirin in the 7 days prior to randomization, although the interaction for treatment by prior aspirin was not statistically significant when using the conservative threshold of P<0.05. Power to detect an interaction effect is generally less than that for a main effect. Failure to identify significant interaction does not imply homogeneity of effects and could be due to low power. In fact, the differences in the magnitude of subgroup-specific treatment effects (HR=0.76 in the aspirin group vs. HR=0.96 in non-aspirin group) suggests a degree of treatment effect heterogeneity. However, results from subgroup analyses must be interpreted with caution since these can increase both false positive and false negative errors. Therefore, the observation in this study should primarily be hypothesis-generating with necessary confirmation coming from a future study.

Interestingly, a recent publication based on re-analyses of clinical trial data with aspirin versus control in acute minor stroke and TIA demonstrated that aspirin substantially reduces the risk of early recurrent stroke and reduces disability after recurrent stroke.13 Thus, aspirin’s preventive effect in the early period after acute cerebral ischemic events may be substantial, and a residual aspirin effect during the first week of treatment in SOCRATES may have provided additional benefit to ticagrelor, by conferring partial dual antiplatelet therapy.

An enhanced antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel with aspirin was seen in several studies. Studies investigating microembolization from atherosclerotic cerebral arteries in connection with acute cerebral ischemic events showed a reduction in events with dual antiplatelet therapy.14,15 Furthermore, the CHANCE trial of Chinese patients with minor ischemic stroke or TIA found a 32% relative risk reduction of stroke at 90 days with a regimen including clopidogrel with aspirin versus one that included only aspirin.1 The on-going POINT (Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) trial is investigating whether the promising results of clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin in acute cerebral ischemic events demonstrated in CHANCE could be confirmed in a Western population.16

The higher vascular disease burden in the prior-aspirin group may reflect that aspirin was used more frequently for prevention of atherothrombotic diseases in this subgroup. Potentially, patients with a higher vascular event risk in the prior-aspirin group, and with the index event occurring during aspirin treatment (‘breakthrough stroke’), may have benefited more from intense antiplatelet therapy provided by ticagrelor.17 However, a large proportion of patients in the prior-aspirin group only received ‘acute treatment’ prior to randomization, thus most likely after the start of the index event, and these patients benefited from ticagrelor at least as much as those with aspirin ‘chronic treatment’ prior to randomization. Diminishing clinical effect of aspirin with long-term use has been hypothesized, and could explain higher event rates in those previously taking aspirin who were randomized to aspirin and a trend towards better treatment effect of ticagrelor;13,17 however, this would not explain the similar effect seen in those who received only acute aspirin treatment prior to randomization. The observation that patients who received only acute treatment with aspirin after the index event had a favorable outcome may indicate the benefit of dual antiplatelet with ticagrelor and aspirin in the acute setting of cerebral ischemic events. Finally, atherosclerotic phenotyping could not confirm an increased prevalence of ipsilateral atherosclerotic stenosis in the prior-aspirin group; a higher prevalence of ipsilateral atherosclerotic stenosis could have rendered this subgroup more responsive to ticagrelor, as shown in a recent SOCRATES publication.18 Although atherosclerotic phenotype was more common in the ‘chronic treatment’ than in the ‘acute treatment’ prior-aspirin group, this difference did not translate into a differentiated treatment effect.

Taking all these findings together, it is reasonable to assume that the initial dual antiplatelet effect from aspirin intake 7 days prior to randomization during the period with highest risk for new stroke events was the major contributor to the potential treatment effect of ticagrelor in the prior-aspirin group, observed in the 7-day analysis, as well as at 90 days.

In a secondary publication from the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 trial (Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Prior Heart Attack Using Ticagrelor Compared to Placebo on a Background of Aspirin-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 54), addition of ticagrelor to aspirin for long-term secondary prevention in patients with coronary disease provided a significant relative risk reduction of stroke by 25%, but with more major bleeding (HR 2.32; 95% CI 1.68–3.21, P<0.001).19 In CHANCE, major bleeding event rates were similar for aspirin alone and the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin.1 In SOCRATES, the number of major bleeding events were few and similar for ticagrelor and aspirin.12 Overall, major or minor bleeding tended to be more common on ticagrelor than aspirin in the prior-aspirin group, which may reflect a more pronounced antiplatelet effect, while severe, life-threatening bleeding rates were not.

Although this global dataset is of reasonable size to justify subgroup analyses, the results from these analyses should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. The primary outcome in SOCRATES was not statistically significant. The prior-aspirin usage was not randomly assigned and there were differences in baseline factors among the subgroups; however, the key comparator of interest was randomized: treatment with ticagrelor or aspirin. In addition, the effect of aspirin intake prior to randomization would gradually disappear during the first treatment week, providing only a partial dual antiplatelet therapy in the ticagrelor prior-aspirin subgroup. Therefore, the findings regarding bleeding risk and efficacy of combining ticagrelor and aspirin versus aspirin alone in patients with acute stroke or TIA need to be confirmed in a randomized trial.

In conclusion, the results of the present analyses and the literature on dual antiplatelet therapy in patients with acute cerebral ischemic events support the hypothesis that the combination of ticagrelor and aspirin may be a more effective treatment than aspirin alone in preventing subsequent ischemic events in patients with acute minor ischemic stroke or TIA. This hypothesis will be addressed in the Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated with Ticagrelor and ASA for Prevention of Stroke and Death (THALES) trial (clinicaltrials.gov, NCT03354429).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Editorial support (formatting tables and figures, coordinating reviews and preparing the manuscript for submission) was provided by Jackie Phillipson (Zoetic Science, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, Macclesfield, UK); this assistance was funded by AstraZeneca.

Disclosures

Wong L.K.S. reports honoraria as a member of a steering committee for Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca (modest), and Bayer (modest); honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contributions to advisory boards, or oral presentations from Bayer (modest), Sanofi-Aventis (modest), Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim (modest), and Pfizer (modest). Amarenco P. reports receipt of significant research grant support from AstraZeneca, Sanofi and Bristol Myers-Squibb (for TIA registry.org), the French Government and Pfizer (for the TST trial), and Boston Scientific (for the WATCH-AF registry). He has received modest consultant/advisory board fees from Amgen and Bristol Myers Squibb. He has also received modest honoraria from Amgen (speaker activities), Pfizer (SPIRE program Executive Committee), AstraZeneca (SOCRATES trial Executive Committee), and Kowa (PROMINENT Executive committee), and significant honoraria from Bayer (XANTUS Executive Committee), AstraZeneca (THALES Executive Committee), and Fibrogen (ALPINE program trials DSMB member). Albers G.W. reports equity interest and consulting fees from iSchemaView (significant), and consultant fees from Janssen (modest). Denison H., Held P., Himmelmann A., Knutsson M., and Ladenvall P. are employees of AstraZeneca (all significant). Easton J.D. received research grant support from AstraZeneca (significant) for the SOCRATES trial (NCT01994720) and receives research support (significant) from the NIH/the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke as a co-principal investigator for the POINT trial (U01 NS062835-01A1); POINT received some free study drug and placebo from Sanofi (NCT00991029). He also receives support (modest) from Boehringer Ingelheim as a consultant for the planning and conduct of the RE-SPECT ESUS (NCT02239120) trial. Evans S. is a statistical consultant to AstraZeneca (significant). Kasner S.E. reports a grant from Astra Zeneca during the conduct of this study; as well as grants from Bayer (significant), Bristol Myers Squibb, WL Gore (significant), and Acorda (all others modest); consulting fees from Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Abbvie, Medtronic, and Johnson & Johnson (modest), outside the submitted work. Minematsu K. reports honoraria (all modest for seminar presentations) from: Bayer Yakuhin, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Boehringer-Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Cooperation, Japan Stryker, Kowa, Nihon Medi-Physics Co, BMS, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma Co, Daiichi Sankyo, Asteras Pharma, and immediate family members have received modest honoraria from Nippon Chemiphar. He has also received modest honoraria (for a supervising brochure) from Sawai Pharmaceuticals, and modest fees (advisory board) from CSL Behring and Medico’s Hirata. Molina C. serves in the Steering Committee (significant) of CLOTBUST-ER trial (Cerevast); SOCRATES (AstraZeneca), IMPACT-24b (Brainsgate), REVASCAT (Fundació Ictus Malaltia Vascular). He has received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards, or oral presentations from: AstraZeneca (modest), Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, BMS, Covidien, Cerevast, Brainsgate. Molina C. has no ownership interest and does not own stocks of any pharmaceutical or medical device company. Wang Y. reports research grant support from AstraZeneca (modest). Johnston S.C. reports receiving research grants from the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH). He has received research support from Biogen (consulting agreement and compensation agreement – both significant), and was a consultant to AstraZeneca as the Committee Chair (significant) for SOCRATES. He has also received travel and hotel expenses from AstraZeneca to attend meetings.

References

- 1.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, Liu L, Wang D, Wang C, et al. CHANCE Investigators Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:11–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amarenco P, Lavallée PC, Labreuche J, Albers GW, Bornstein NM, Canhão P, et al. TIAregistry.org Investigators One-year risk of stroke after transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1533–1542. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, Easton JD, Evans SR, et al. SOCRATES Steering Committee and Investigators Ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:35–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group. CAST: randomized placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349:1641–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group. The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349:1569–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, Li H, Johnston SC, Lin Y, et al. CHANCE investigators Association between CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele status and efficacy of clopidogrel for risk reduction among patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA. 2016;316:70–78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Husted S, van Giezen JJJ. Ticagrelor: the first reversibly binding oral P2Y12 receptor antagonist. Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;27:259–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5922.2009.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cattaneo M, Schulz R, Nylander S. Adenosine-mediated effects of ticagrelor: evidence and potential clinical relevance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2503–2509. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, Easton JD, Held P, et al. Acute stroke or transient ischemic attack treated with aspirin or ticagrelor and patient outcomes (SOCRATES) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2015;10:1304–1308. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Caplan LR, Donnan GA, Wolf ME, Hennerici MG. The ASCOD phenotyping of ischemic stroke (updated ASCO phenotyping) Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;36:1–5. doi: 10.1159/000352050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Easton JD, Aunes M, Albers GW, Amarenco P, Bokelund Singh S, Denison H, et al. SOCRATES Steering Committee and Investigators Risk for major bleeding in patients receiving ticagrelor compared with aspirin After TIA or acute ischemic stroke in the SOCRATES Study. Circulation. 2017;136:907–916. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothwell PM, Algra A, Chen Z, Diener HC, Norrving B, Mehta Z. Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;388:365–375. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30468-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Markus HS, Droste DW, Kaps M, Larrue V, Lees KR, Siebler M, Ringelstein EB. Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin in symptomatic carotid stenosis evaluated using Doppler embolic signal detection the clopidogrel and aspirin for reduction of emboli in symptomatic carotid stenosis (CARESS) trial. Circulation. 2005;111:2233–2240. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000163561.90680.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong KS, Chen C, Fu J, Chang HM, Suwanwela NC, Huang YN, et al. CLAIR study investigators Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus aspirin alone for reducing embolisation in patients with acute symptomatic cerebral or carotid artery stenosis (CLAIR study): a randomised, open-label, blinded-endpoint trial. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:489–497. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, Barsan W, Battenhouse H, Conwit R, et al. Platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2013;8:479–483. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee M, Saver JL, Hong KS, Rao NM, Wu YL, Ovbiagele B. Antiplatelet regimen for patients with breakthrough strokes while on aspirin. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017;48:2610–2613. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.017895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amarenco P, Albers GW, Denison H, Easton JD, Evans SR, Held P, et al. Efficacy and safety of ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischaemic attack of atherosclerotic origin: a subgroup analysis of SOCRATES, a randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:301–310. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonaca MP, Goto S, Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Storey RF, Cohen M, et al. Prevention of stroke with ticagrelor in patients with prior myocardial infarction: insights from PEGASUS-TIMI 54 (Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Prior Heart Attack Using Ticagrelor Compared to Placebo on a Background of Aspirin-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 54) Circulation. 2016;134:861–871. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.