Abstract

Background and Purpose

Taurine (2-aminoethansulfolic amino acid) exerts neuroprotective actions in experimental stroke. Here, we investigated the effect of taurine in combination with delayed tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) on embolic stroke.

Methods

Rats subjected to embolic middle cerebral occlusion (MCAO) were treated with taurine (50 mg/kg) at 4 hours in combination with tPA (10 mg/kg) at 6 hours. Control groups consisted of ischemic rats treated with either taurine (50 mg/kg) or saline at 4 hours or tPA (10 mg/kg) alone at 2 or 6 hours after MCAO.

Results

We found that combination treatment with taurine and tPA robustly reduced infarct volume and neurological deficits 3 days after stroke, whereas treatment with taurine alone had a less significant protective effects. tPA alone at 6 hours had no effects on infarct volume but instead induced intracerebral hemorrhage. The combination treatment with taurine prevented tPA-associated hemorrhage and reduced intravascular deposition of fibrin/fibrinogen and platelets in downstream microvessels and hence improved microvascular patency. These protective effects are associated with profound inhibition of CD147-dependent MMP-9 pathway in ischemic brain endothelium by taurine. Notably, targeted inhibition of CD147 by intracerebroventricular injection of the rat CD147 siRNA profoundly inhibited ischemia-induced and tPA-enhanced MMP-9 activity in ischemic brain endothelium and blocked tPA-induced cerebral hemorrhage. Finally, the combination treatment with taurine and tPA improved long-term outcome at least 45 days after stroke compared with saline-treated group.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that taurine in combination with tPA may be a clinically feasible approach toward future attempts at combination stroke therapy.

Keywords: Taurine, CD147, tissue plasminogen activator, thrombolysis, stroke

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and permanent disability worldwide. To date, intravenous administration of tissue-type plasminogen activator (IV tPA) remains the only FDA-approved drug therapy for achieving cerebral reperfusion, but its use is given to only 3–8.5% of stroke cases in the United States.1 This is mainly related to increased risks of intracranial hemorrhage.1 It is well-recognized that IV tPA beyond 3 hours of stroke onset significantly increases cerebral bleeding although it could be extended to a 3–4.5 hour time window in carefully selected patients.2 Thus, there is great interest in developing adjuvant drugs to use with tPA to extend its treatment time window to a broader patient population.

Taurine (2-aminoethansulfolic acid) is the most abundant endogenous sulphur-containing amino acid in animals and humans. It has many important biological functions in the body, such as bile acid conjugation, osmoregulation, anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, membrane stabilization, and calcium homeostasis.3 Taurine has been shown to be neuroprotective through multiple mechanisms of action in acute ischemic stroke and traumatic brain injury.4,5 For example, taurine can downregulate ischemia/hypoxia- and glutamate-induced neuronal apoptosis by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and maintaining intracellular Ca 2+ homeostasis.6,7 Taurine can also suppress ischemic inflammation in the brain by reducing cytokine production and neutrophil infiltration by inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kB) pathway.8

Many neuroprotective agents, some promising, have been tested as adjunctive therapy with tPA to reduce its neurotoxicity, risk of hemorrhage, and reperfusion injury in an effort to increase its neuroprotection and therapeutic time window, however, few have proven to be efficacious in clinical trials.9,10 Compared to other neuroprotective agents, taurine may have several unique advantages: (1) taurine has many important endogenous biological functions; (2) taurine, an organic compound with small molecular weight (125 Da), can readily cross the blood-brain barrier into brain parenchyma;11 (3) the pharmacokinetics and metabolism of taurine is well characterized in both animals and humans and up to 3,000 mg per day of taurine as supplementation is generally recommended. At this dose, excess taurine can be excreted by the kidneys with minimal toxicity.3 In clinical practice, taurine supplementation is considered to be safe and helpful as an adjuvant therapy for congestive heart failure, high blood pressure, and diabetes.12–14 Based on these unique advantages, multiple health benefits, and limited side effects, we proposed taurine as an ideal neuroprotective agent for combined therapy with IV t-PA. In this study, we aimed to determine whether and how taurine extends the therapeutic time window for IV tPA in a rat model of embolic stroke.

Materials and Methods

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. This manuscript adheres to the AHA Journals' implementation of the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Louisiana State University Health Science Center Shreveport and Penn State University College of Medicine. A detailed Methods section is provided in the online-only Supplemental Material. The Checklist of Methodological and Reporting Aspects is shown in Suppl. Table I. A diagram of the experimental design and animal groups is shown in Suppl. Figure I. The number of animals used in each experimental treatment group is summarized in Suppl. Table II.

Stroke Model

Sprague-Dawley rats (male, weighing 280–340 g) were subjected to embolic middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) according to the standard operating procedure in our laboratory.15

Experimental Protocols

Ischemic rats were randomly assigned to the following treatment or control groups: treated with 0.9% saline as a vehicle, early tPA at 2 hours, delayed tPA at 6 hours, taurine at 4 hours, or taurine at 4 hours plus tPA at 6 hours. All stroke outcome measurements were performed by investigators blinded to the treatments. Human recombinant tPA (Alteplase, Genentech, Inc., San Francisco, CA) was intravenously administered at a dose of 10 mg/kg (10% as a bolus and 90% as a 30 min infusion) using a syringe infusion pump (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA). 10 mg/kg Alteplase is a standard dose typically used in rodents.16–18 Taurine (T0625-Sigma-Aldrich, purity >99%; molecular weight 125.15 Da) at a dose of 50 mg/kg (dissolved in 0.9% saline) per day was intravenously administered starting 4 hours after MCAO. Published studies have shown that taurine at a dose of 40–50 mg/kg per day exerts potent neuroprotection in a filament MCAO model in rats.19,20 The effects of taurine on tPA-induced brain hemorrhage and acute stroke injury were examined at 3 days, in which taurine was given once daily. The effects of taurine on long-term outcomes were assessed up to 45 days after stroke, in which taurine was given once daily for the first 7 days. In some experiments, intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of CD147 siRNA or scramble control siRNA was performed (Suppl. Figure II) as previously described (Please see Supplemental Methods for detail).21

Infarct volume, intracerebral hemorrhage, BBB permeability, and neurological deficits

Infarct volume was measured in TTC-stained coronal sections on day 3 after MCAO.22 Hemoglobin levels were measured in the TTC-stained sections by a spectrophotometric assay using Drabkin reagent (Sigma-Aldrich).23 It has been shown that hemoglobin measurements can be simultaneously performed on TTC-stained sections.24 The modified Bederson score25 (global neurological function), foot-fault test26 (motor impairment and forelimb coordination), and modified neurological severity score (mNSS)27 (a composite of motor, sensory, reflex, and balance tests) were performed by a blinded investigator. In a separate set of experiment, early impairment of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability was determined by measuring the extravasation of Evans blue dye (Sigma-Aldrich) in the brain tissue 12 hours after MCAO.22

Western blot and gelatin zymography

Protein extracts were obtained from the cerebral cortices (bregma +1 to −2 mm) and the isolated cerebral microvessels (Suppl. Figure IIIA). These assays were performed as described previously.22,28

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described.22,28 The number of vessels positively stained with fibrin/fibrinogen and thrombocytes were counted in the ischemic boundary zone (Suppl. Figure IIIB). The gelatinase (MMP-2/-9) activity in brain tissue was detected by in situ zymography. All immunostaining data was analyzed by a blinded investigator and data are presented as the density of immunoreactive vessels relative to the imaged area (mm2). Cerebral microvascular patency was assessed using the FITC-labeled dextran method.28

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. The GraphPad Prism 5 software package was used for statistical analysis. The normality of data were assessed with the D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus test. For normally distributed variables, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test were used to assess differences between groups. If only 2 groups were compared, an unpaired, 2-tailed Student t test, was applied. The Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney U tests were used to explore differences between groups in non-normally distributed variables. Nonparametric functional outcome scores were compared by Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc Dunn corrections. For comparison of survival data, the log-rank test was used. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Effects of taurine on tPA-induced intracerebral hemorrhage and acute stroke outcome

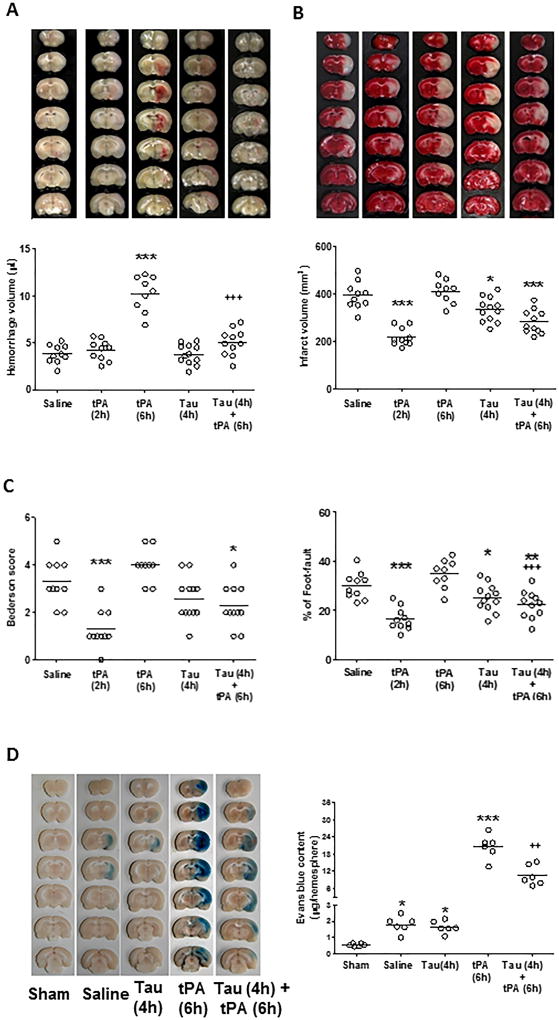

As expected, early IV tPA at 2 hours reduced infarct volume, and delayed IV tPA at 6 hours had no effect on infarct volume but instead promoted intracerebral hemorrhage (Figure 1A and 1B). Taurine alone at 4 hours had no detectable effect on hemorrhage, but the combination treatment with taurine profoundly reduced tPA-associated hemorrhage. Moreover, the combination treatment with taurine and delayed tPA was more effective than the treatment with taurine alone in reducing infarct volume (Figure 1B) and neurological deficits (Figure 1C) 3 days after stroke. Neurological deficits were determined by the Bederson score and the foot-fault test (Figure 1C). Physiological parameters remained within normal range in all experimental groups (Supp. Table III). In this model, the 3-day mortality rates in stroke rats treated with saline, early tPA (at 2 h), late tPA (at 6 h), taurine (at 4h), and taurine (at 4h) plus tPA (at 6h) were 29%, 17%, 47%, 20%, and 21%, respectively. But due to the limited animal numbers studied here, there were no statistically significant differences between these groups (Suppl. Table IV).

Figure 1.

Taurine prevents tPA-associated intracerebral hemorrhage and reduces acute stroke injury. A and B, Representative images of unstained coronal sections (A, upper panels) showing intracerebral hemorrhage (red color) and TTC-stained coronal sections (B, upper panels) showing tissue infarction (white color) in the indicated groups 72 hours after stroke. Quantitative analysis of hemorrhage volume (A, lower panel) and infarct volume (B, lower panel). C, Neurological deficits were assessed by Bederson score (left) and foot-fault test (right). n= 9–12 rats per group. Tau: taurine. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs Saline; +++P<0.001 vs tPA (6h). D, (Left) Representative pictures of coronal sections showing Evans blue extravasation in the indicated groups 12 hours after stroke onset. (Right) Quantitative analysis of Evans blue extravasation in the brain parenchyma. n=6 per group. *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 vs Saline; ++P<0.01 vs tPA (6h).

Early disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) after thrombolytic therapy predicts hemorrhage in patients with acute stroke.29 Therefore, we additionally investigated the effect of taurine on ischemia-induced and tPA-enhanced early impairment of BBB permeability assessed by Evans blue extravasation at 12 hours after stroke onset (i.e. 6 hours after delayed tPA). Evans blue extravasation into the brain parenchyma was at similar low levels in the saline- and taurine alone groups, but dramatically increased (over 20-fold) in the tPA alone group, and importantly, the tPA-associated increase was significantly reduced by co-treatment with taurine at 4 hours after onset of ischemia (Figure 1D). As expected, Evans blue extravasation was not visualized in the sham-operated brain.

Effects of taurine on tPA-enhanced MMP-9 activity in ischemic brain microvessels

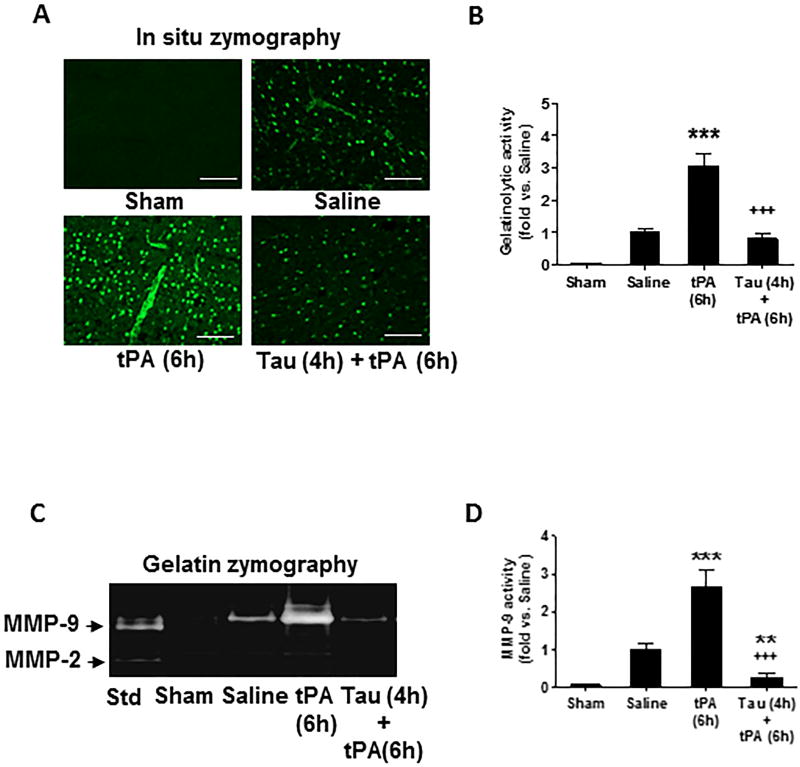

Increased matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), in particular MMP-9, plays a pivotal role in tPA-induced hemorrhage after stroke.30 In situ zymography was performed to assess gelatinase (MMP-2/MMP-9) activity in the brain at 24 hours after stroke. Gelatinatic activity was very low in sham-operated brain, but significantly induced by MCAO and further augmented by delayed IV tPA (Figure 2A and 2B). Combination treatment with taurine markedly reduced ischemia-induced and tPA-enhanced gelatinolytic activity. Notably, taurine almost completely abolished gelatinolytic activity in ischemic brain microvessels (Figure 2A and 2B). Next, gelatin zymography was performed to assess MMP profiles in brain microvessels isolated at 24 hours after stroke. MMP-9 activity was significantly increased by ischemia and further enhanced by delayed tPA, and these effects were profoundly inhibited by taurine, whereas MMP-2 activity was rarely detectable in sham control and also not altered by either ischemia, tPA, or taurine (Figure 2C, 2D).

Figure 2.

Taurine inhibits tPA-enhanced gelatinolytic activity in ischemic brain microvessels 24 hours after stroke. A, Representative images of in situ zymography in fresh-frozen brain sections in the indicated groups. Images were acquired from peri-infarct cortex. Bar= 50 µm. B, Semi-quantitation of gelatinolytic activity was analyzed by green fluorescence intensity. Data were presented as fold change relative to saline-treated group. n=5 per group. ***P<0.001 vs saline; +++P<0.001 vs tPA (6h). C, Representative images of gelatin zymography for MMP-2/-9 activity using isolated brain microvessels (a pool of 3 rats per group). D, Semi-quantitation of MMP-9 bands was analyzed by densitometry. Std: standard human MMP-2/-9 mixed marker. Data are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs Saline; +++P<0.001 vs tPA (6h).

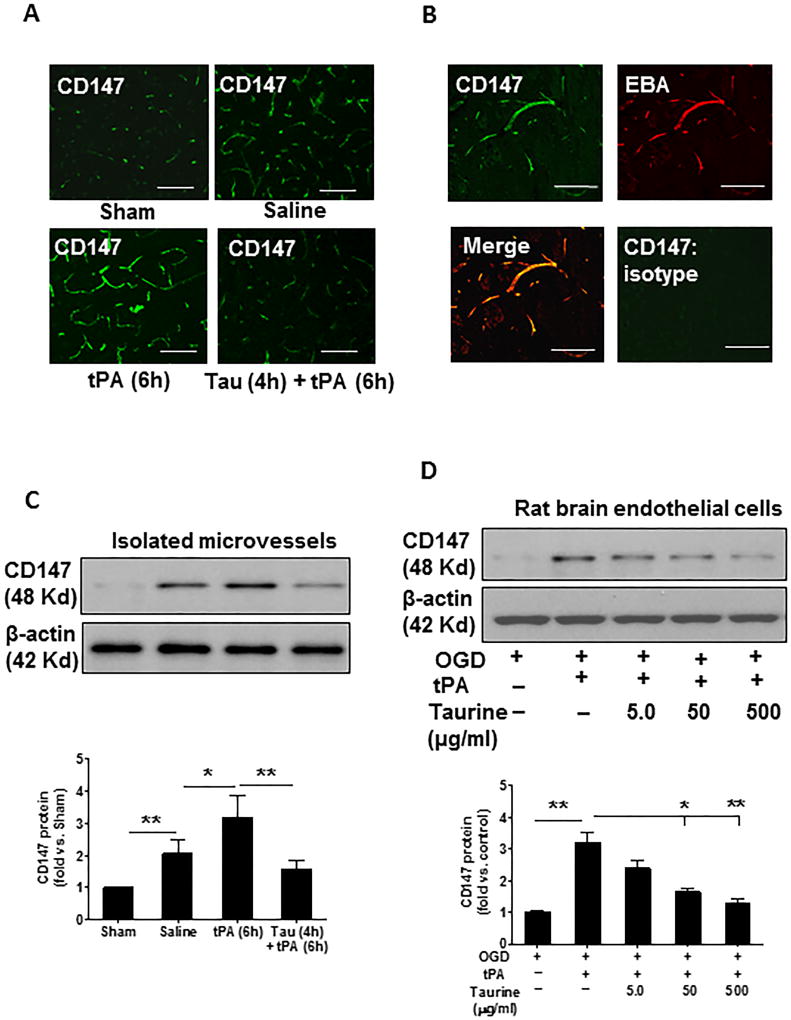

Effects of taurine on tPA-enhanced CD147 expression in ischemic brain microvessels

We have reported that CD147 is rapidly increased in ischemic brain endothelium after MCAO in mice.28 Here, we examined CD147 expression after embolic stroke in rats. Immunohistochemistry showed that MCAO robustly induced CD147 expression in ischemic brain endothelium and that was further augmented by delayed administration of tPA (Figure 3A). Double immunostaining confirmed that CD147 immunoreactivity colocalized almost exclusively with brain microvessels (marked by EBA) (Figure 3B). Notably, the ischemia-induced and tPA-enhanced CD147 expression was profoundly inhibited by taurine (Figure 3A). These findings were solidly verified by Western blot analysis of CD147 protein in brain microvessels isolated at 24 h after stroke (Figure 3C). Moreover, we found that tPA (20 µg/ml) robustly stimulated CD147 expression in cultured rat brain microvascular endothelial cells exposed to oxygen and glucose deprivation (OGD) and this effect was dose-dependently inhibited by taurine (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Taurine inhibits ischemia-induced and tPA-enhanced CD147 in ischemic brain microvessels 24 hours after stroke. A, Representative images of immunofluorescence staining showing the expression and distribution of CD147 in the indicated groups. B, Double immunostaining showing the colocalization of CD147 (green) with brain microvessels (marked by staining for EBA, the endothelial barrier antigen, red). Negative control staining with isotype-matched control antibody did not show detectable labeling. Images were acquired from peri-infarct cortex. Bar=50 µm. C, Representative images of western blots showing CD147 protein levels in isolated brain microvessels (a pool of 3 rats per group) from the indicated groups. D, Representative images of western blots showing CD147 protein levels in cultured rat brain microvascular endothelial cells subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) and treated with tPA (20 µg/ml) and different doses of taurine as described in Method section. Semi-quantification of immunoblots was analyzed by densitometry. Data are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01.

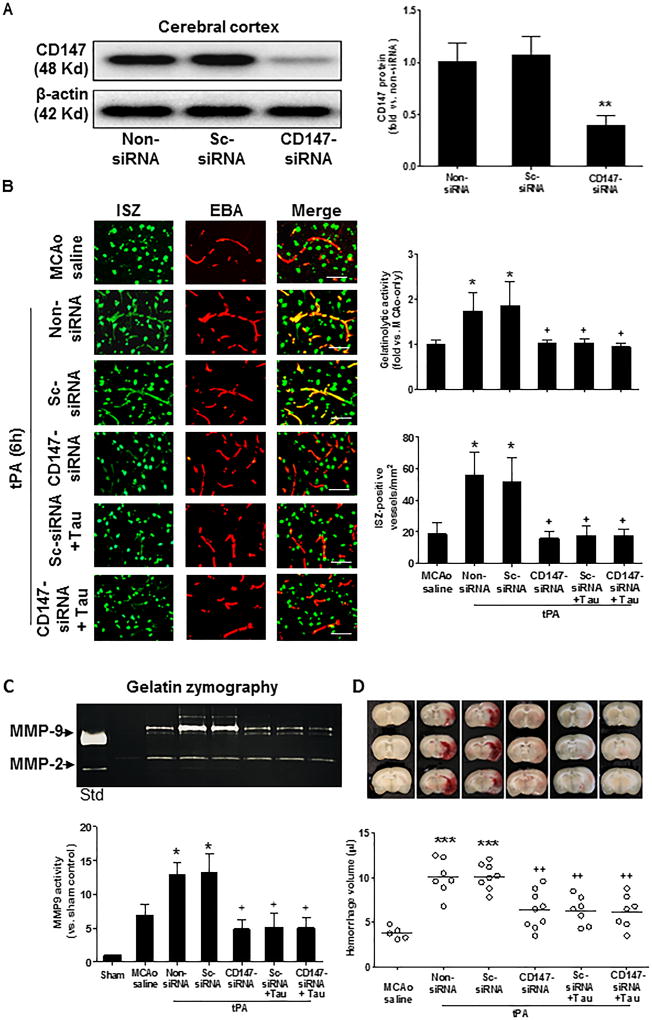

Effects of CD147 expression on tPA-induced intracerebral hemorrhage associated with cerebral microvascular MMP-9 activity

Subsequently, we determined whether CD147 is important for tPA-induced MMP-9 and hemorrhagic transformation. CD147 siRNA, scramble control siRNA (sc-siRNA), or siRNA delivery reagent only (as vehicle) was infused into the lateral ventricles in the ipsilateral hemisphere by intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection within 1 hour after ischemia onset (Suppl. Figure IIA). The injected siRNA was localized to cytoplasmic compartments with perinuclear location (marked by DAPI) (Suppl. Figure IIB). Western blot analysis showed that CD147 siRNA markedly reduced CD147 protein levels in the ischemic cortex, but sc-siRNA had no effect (Figure 4A). In situ zymography (ISZ) showed that CD147 siRNA, but not sc-siRNA, decreased the number of ISZ-positive vessels in the ischemic cortex (Figure 4B). Furthermore, gelatin zymography analysis of isolated brain microvessls showed that CD147 siRNA, but not sc-siRNA, suppressed MMP-9 activity (Figure 4C). Notably, the siRNA-mediated inhibition of CD147 in the brain almost completely blocked delayed tPA-induced brain hemorrhage (Figure 4D). Moreover, very similar effects were observed between the taurine alone, CD147 siRNA alone, and taurine plus CD147 siRNA treatments, with respect to inhibition of MMP-9 examined either by in situ zymography (Figure 4B) or by gelatin zymography (Figure 4C), as well as to the delayed tPA-induced hemorrhage (Figure 4D). These results support our hypothesis that taurine blocks the tPA-associated hemorrhage through inhibition of a CD147-dependent MMP-9 pathway in ischemic brain endothelium after ischemic stroke.

Figure 4.

Silencing CD147 inhibits tPA-enhanced gelatinolytic activity in ischemic brain microvessels and blocks tPA-associated intracerebral hemorrhage 24 hours after stroke. Intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of CD147 siRNA, scramble control siRNA (sc-siRNA) or non-siRNA (vehicle only) was performed within 1 hour of ischemia onset, followed by IV tPA at 6 hours. A, Representative images of western blots showing CD147 protein levels detected in the cerebral cortex in the indicated groups. Semi-quantitation of immunoblots was analyzed by densitometry. Data are mean ± SEM from 3 independent experiments. **P<0.01 vs sc-siRNA or non-siRNA. B, Representative images of double immunostaining of in situ zymography (ISZ) with EBA (the endothelial barrier antigen marker) in the indicated groups. Images were acquired from peri-infarct cortex. Bar=50 µm. Total gelatinase activity was determined by green fluorescence intensity and data were presented as fold change relative to the non-siRNA group (vehicle only). The number of ISZ-positive vessels was measured as described in the Methods section. n=5 per group. *P<0.05 vs MCAO saline, and +P<0.05 vs sc-siRNA or non-siRNA. C, Representative images of gelatin zymography for MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity in the cerebral cortex in the indicated groups. Std: standard human MMP-2/-9 mixed marker. Semi-quantitation of MMP bands was analyzed by densitometry. Data are mean ±SEM from 3 independent experiments. *P<0.05 vs MCAO saline, and +P<0.05 vs sc-siRNA or non-siRNA. D, Representative images of unstained coronal sections showing intracerebral hemorrhage (red color) and quantitative analysis of hemorrhage volume in the indicated groups. n= 7–9 rats per group. ***P<0.001 vs MCAO saline, and ++P<0.01 vs sc-siRNA or non-siRNA.

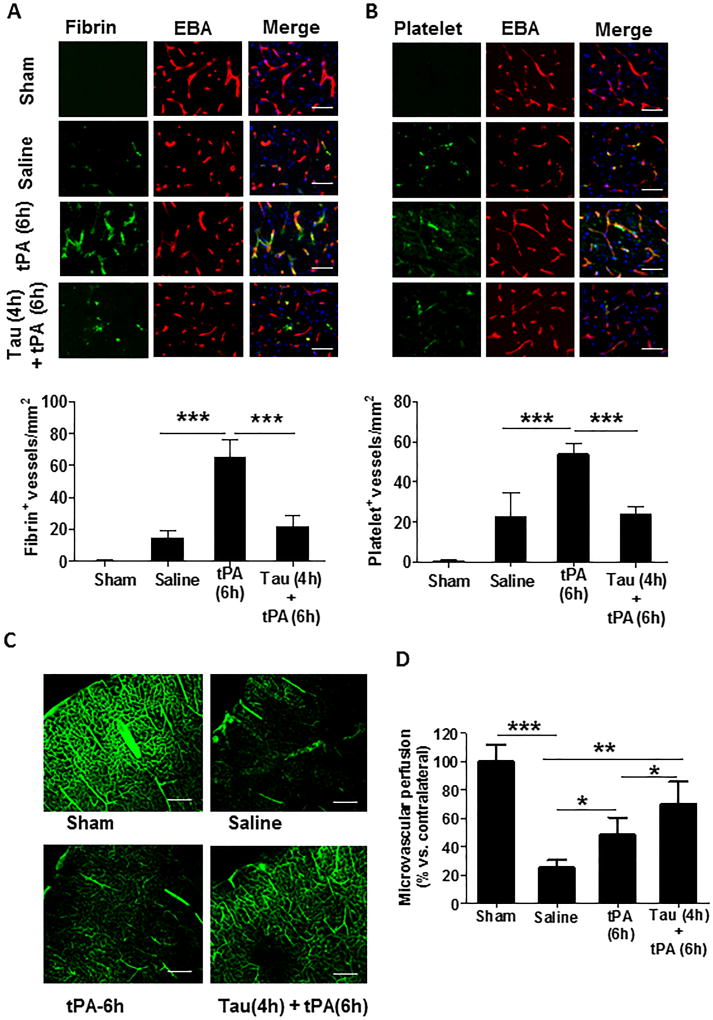

Effects of taurine on microvascular thrombus formation and cerebral vascular patency

Intravascular fibrin/fibrinogen deposition and platelet accumulation are two major factors contributing to secondary microvascular thrombus formation after ischemic stroke.31 Double immunofluorescence staining was performed to examine intravascular fibrin/fibrinogen and thrombocytes/platelets deposition in cerebral microvessels (marked by EBA). Fibrin/fibrinogen (Figure 5A) and thrombocytes/platelets (Figure 5B) were rarely detected in sham-operated, non-ischemic rats, and also minimally detected within the saline-treated stroke rats possibly due to very low cerebral perfusion in downstream microvessels without tPA thrombolysis in this stroke model induced by blood clots. However, both the fibrin/fibrinogen deposition and platelet accumulation in downstream microvessels were markedly increased in stroke rats with delayed tPA, and these increases were profoundly inhibited by combination treatment with taurine (Figure 5A and 5B). Consistent with these findings, microvascular patency (determined by cerebral area perfused with FITC–dextran) markedly dropped below 25% of the baseline (sham) in the saline-treated rats, but it restored to 50% and 70% of baseline in stroke rats with delayed tPA alone or in combination with taurine, respectively (Figure 5C, 5D).

Figure 5.

Taurine reduces intravascular fibrin- and platelet- deposition correlated with improved microvascular patency 24 hours after stroke. A and B, Representative images of double immunofluorescence staining showing fibrin (A, upper panel) or thrombocytes (B, upper panel) deposited in brain microvessels (marked by EBA staining). Images were acquired from the peri-infarct cortex. Bar=50 µm. Number of fibrin-positive (A, lower panel) and thrombocyte-positive (B, lower panel) vessels was counted as described in the Methods section. n=5/group. ***P<0.001. C, Representative images showing microvascular FITC-dextran perfusion in the indicated groups. Scale bars: 200 um. D, Quantitative data are expressed as the percentage of the microvascular area perfused with FITC-dextran in the ipsilateral versus contralateral hemisphere. n=5 rats per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, and *P<0.001.

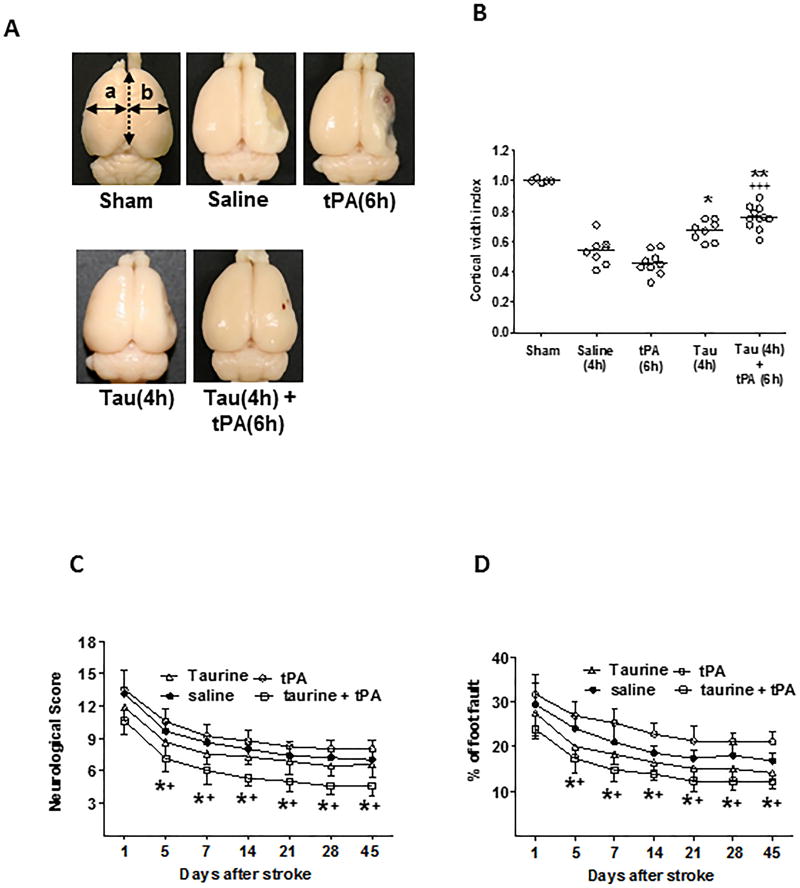

Effects of taurine in combination with delayed tPA on long-term stroke outcome

Although taurine’s neuroprotection has been well documented in experimental stroke, all previous studies were performed only in the early phase (1–4 days) after stroke.6,8,19,20 Here, we investigated whether taurine’s neuroprotection remains significant during longer periods of time after stroke. Cortical width index (CWI) is used as a measure of brain atrophy as previously described.17,32 Severe brain atrophy was observed in the saline-treated stroke rats at 45 days after stroke. Treatment with taurine alone increased CWI by 27% and the combined treatment with taurine and tPA increased CWI by 45%, in contrast, tPA alone showed no significant effect on CWI (Figure 6A and 6B). Consistent with these findings, taurine in combination with tPA significantly improved neurological functions, while taurine alone was less effective, as determined by the modified neurological severity score and foot-fault test within the 45 days of follow-up (Figure 6C and 6D). As expected, tPA alone did not exert any beneficial neurological effects when it was administered 6 hours after stroke. In this model, the 45-day mortality rates in MCAO rats treated with saline, tPA(at 6 h), taurine (at 4h), and taurine (at 4h) plus tPA (at 6h) were 47%, 55%, 43%, and 31%, respectively. But due to the limited animal numbers studied here, there are no statistically significant differences between these groups (Suppl. Table V).

Figure 6.

Taurine in combination with delayed tPA ameliorates long-term neurological outcome. A, Representative images showing brain atrophy in stroke rats treated with saline (4h), tPA (6h), taurine (4h), or taurine (4h) + tPA (6h). Sham-operated rats served as a control. B, Cortical width index was measured for quantitative evaluation of brain atrophy as described in Method. C and D, Neurological deficits were assessed by the modified neurological severity score (C) and the foot fault test (D). A-D: n= 8–11 rats per group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs saline; +P<0.05 and +++P<0.001 vs tPA (6h).

Discussion

The present study, for the first time, demonstrates that combination treatment with taurine at 4 hours extends the therapeutic time window of thrombolysis with tPA to 6 hours and improves long-term neurological outcome in the rat after embolic stroke. Mechanistically, we have found two important and previously undescribed beneficial actions of taurine for ischemic stroke. First, taurine may reduce the risk of hemorrhagic transformation associated with delayed tPA by suppressing the CD147–dependent MMP-9 pathway in ischemic brain endothelium. Second, taurine may improve the efficacy of thrombolytic therapy by reducing secondary thrombus formation in downstream microvessels and hence ameliorating cerebral vascular patency.

Among currently available stroke models, the embolic MCAO is most suitable for preclinical investigation of thrombolytic therapy.33 In this study, we investigated whether and how taurine extends the therapeutic time window for IV tPA, using combined treatment with taurine at 4 h and tPA at 6h after embolic MCAO in the rat. This combination modality is appropriate and has been previously established to extend the therapeutic window for tPA to 6 hours after embolic MCAOin rats with other neuroprotective agents such as atorvastatin, minocycline, and the proteasome inhibitor ps-519.34–36 The therapeutic window of tPA is 2 to 3h after embolic MCAO in rodents. It has been shown that a standard rodent dose of tPA (10 mg/kg) lost its effectiveness beyond 4 hours after embolic MCAO in rats, and instead increased infarct volume as well as hemorrhagic transformation.37 Treatment with neuroprotective agents prior to IV tPA could block ischemic core enlargement and salvage the penumbra as early as possible. This approach might increase the number of acute stroke patients eligible for tPA beyond the 4.5-hour window.

In the present study, the taurine alone treatment caused a mild reduction (approx.15%) in infarct volume, thus the beneficial effect of taurine on tPA’s side effects couldn’t be simply explained by smaller infarct lesions. Since the extents of Infarct size, BBB damage, and secondary microvascular thrombosis are all associated with the development of ischemic brain injury and neurological outcome, we believe that the multiple beneficial actions including profound reductions in infarct size and early BBB disruption, as well as reduced microvascular thrombosis associated with improved cerebral perfusion, which are conferred by the taurine and tPA combination rather than taurine alone, collaboratively contribute to the neuroprotection in acute stroke injury and long-term neurological recovery observed in this study.

The brain endothelium is a major target for tPA-induced blood-brain barrier (BBB) breakdown and hemorrhage in acute stroke. The results of the present study indicate that taurine exerts anti-hemorrhagic actions by primarily targeting the brain endothelium. tPA has been shown to directly activate MMP-9 in the brain endothelium by acting through LDL receptor-related protein (LRP).38,39 In this study, we have found that taurine inhibits tPA-induced brain hemorrhage by interfering with the CD147-dependent MMP-9 pathway in brain endothelium. CD147 is a transmembrane glycoprotein, originally described as an inducer of MMPs. Increased expression of CD147 has been implicated in many human diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and neurological disorders.40 We have reported that CD147 expression in brain endothelium was rapidly increased after ischemic stroke and inhibition of CD147 with a function-blocking antibody attenuates BBB disruption by inhibiting MMP-9 in brain endothelium.28 The results of the present study further reveal a previously undescribed role for CD147 in tPA-induced hemorrhagic transformation by driving MMP-9 activation in brain microvascular endothelial cells after ischemic stroke that can be inhibited by taurine.

Secondary microvascular thrombosis is an obstacle hindering the efficacy of thrombolytic therapy for patients with acute stroke, but there is no effective treatment.41,42 A subset of stroke patients despite successful thrombolysis still exhibit progressive neurological deterioration that is likely related to incomplete reperfusion resulting from microvascular thrombosis.41,42 Prevention of secondary microvascular thrombosis associated with early reperfusion is considered to be essential for successful neuroprotection in stroke.31,43 The results of the present study show that taurine exerts potent anti-thrombotic effects by reducing intravascular fibrin- and platelet- deposition, which in turn reduces downstream microvascular thrombosis and improves cerebral vascular patency. Inhibition of NF-kB and CD147 is probably involved in the mechanisms of microvascular protection by taurine. Taurine is known to inhibit activation of NF-κB (nuclear factor κB) in the brain after ischemic stroke.4,8 It has been shown that upregulation of NF-kB-dependent PAI-1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor-1) pathway in brain endothelium promotes intravascular fibrin- and platelet- deposition after ischemic stroke.44,45 CD147 has been shown to promote platelet rolling, aggregation, and thrombus formation by interacting with platelet glycoprotein VI (GPVI).46,47 We have recently shown that inhibition of CD147 decreased intravascular fibrin- and platelet- deposition, which in turn reduced microvascular thrombosis after acute ischemic stroke.28 On the basis of these observations, we propose that increased CD147 expression in ischemic brain endothelium may promote intravascular platelet accumulation by interacting with platelet GPVI, thereby contributing to microvascular thrombus formation that was inhibited by taurine to improve microvascular patency after thrombolysis with tPA.

In conclusion, our data suggest that taurine in combination with tPA may be a clinically feasible approach toward future attempts at combination stroke therapy.

Future Direction

Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable recommends that after initial evaluations in young, healthy male animals, further studies should be performed in females, aged animals, and animals with comorbid conditions such as hypertension and diabetes.48 In clinical practice, taurine has been used as an adjuvant therapy for these stroke related diseases. The therapeutic effects of taurine therapy alone and with tPA in aged rats and rats with comorbid conditions (hypertension, diabetes) are currently under investigation in our laboratory.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS088719 and NS089991 (Dr. Li).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, Demchuk AM, Fugate JE, Grotta JC, et al. Scientific Rationale for the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Intravenous Alteplase in Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47:581–641. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:101–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menzie J, Prentice H, Wu JY. Neuroprotective mechanisms of taurine against ischemic stroke. Brain Sci. 2013;3:877–907. doi: 10.3390/brainsci3020877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su Y, Fan W, Ma Z, Wen X, Wang W, Wu Q, et al. Taurine improves functional and histological outcomes and reduces inflammation in traumatic brain injury. Neuroscience. 2014;266:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prentice H, Gharibani PM, Ma Z, Alexandrescu A, Genova R, Chen PC, et al. Neuroprotective functions through inhibition of ER Stress by taurine or taurine combination treatments in a rat stroke model. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;975:193–205. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-1079-2_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prentice H, Pan C, Gharibani PM, Ma Z, Price AL, Giraldo GS, et al. Analysis of neuroprotection by taurine and taurine combinations in primary neuronal cultures and in neuronal cell lines exposed to glutamate excitotoxicity and to hypoxia/re-oxygenation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;975:207–216. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-1079-2_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun M, Zhao Y, Gu Y, Xu C. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of taurine against ischemic stroke is related to down-regulation of PARP and NF-κB. Amino Acids. 2012;42:1735–1747. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0885-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Zhang ZG, Chopp M. The neurovascular unit and combination treatment strategies for stroke. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albers GW, Goldstein LB, Hess DC, Wechsler LR, Furie KL, Gorelick PB, et al. Stroke Treatment Academic Industry Roundtable (STAIR) recommendations for maximizing the use of intravenous thrombolytics and expanding treatment options with intra-arterial and neuroprotective therapies. Stroke. 2011;42:2645–2650. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.618850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kang YS. Taurine transport mechanism through the blood-brain barrier in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;483:321–324. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46838-7_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmadian M, Roshan VD, Aslani E, Stannard SR. Taurine supplementation has anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory effects before and after incremental exercise in heart failure. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;11:185–194. doi: 10.1177/1753944717711138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Militante JD, Lombardini JB. Treatment of hypertension with oral taurine: experimental and clinical studies. Amino Acids. 2002;23:381–393. doi: 10.1007/s00726-002-0212-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sirdah MM. Protective and therapeutic effectiveness of taurine in diabetes mellitus: a rationale for antioxidant supplementation. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2015;9:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin R, Zhu X, Li G. Embolic middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) for ischemic stroke with homologous blood clots in rats. J Vis Exp. 2014;91:51956. doi: 10.3791/51956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murata Y, Rosell A, Scannevin RH, Rhodes KJ, Wang X, Lo EH. Extension of the thrombolytic time window with minocycline in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:3372–3377. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Zhao Z, Chow N, Rajput PS, Griffin JH, Lyden PD, et al. Activated protein C analog protects from ischemic stroke and extends the therapeutic window of tissue-type plasminogen activator in aged female mice and hypertensive rats. Stroke. 2013;44:3529–3536. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Chopp M, Teng H, Ding G, Jiang Q, Yang XP, et al. Combination treatment with N-acetyl-seryl-aspartyl-lysyl-proline and tissue plasminogen activator provides potent neuroprotection in rats after stroke. Stroke. 2014;45:1108–1114. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun M, Xu C. Neuroprotective mechanism of taurine due to up-regulating calpastatin and down-regulating calpain and caspase-3 during focal cerebral ischemia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2008;28:593–611. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gharibani P, Modi J, Menzie J, Alexandrescu A, Ma Z, Tao R, et al. Comparison between single and combined post-treatment with S-Methyl-N,N-diethylthiolcarbamate sulfoxide and taurine following transient focal cerebral ischemia in rat brain. Neuroscience. 2015;300:460–473. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakajima H, Kubo T, Semi Y, Itakura M, Kuwamura M, Izawa T, et al. A rapid, targeted, neuron-selective, in vivo knockdown following a single intracerebroventricular injection of a novel chemically modified siRNA in the adult rat brain. J Biotechnol. 2012;157:326–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamada H, Yu F, Nito C, Chan PH. Influence of hyperglycemia on oxidative stress and matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation after focal cerebral ischemia/reperfusion in rats: relation to blood-brain barrier dysfunction. Stroke. 2007;38:1044–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000258041.75739.cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sumii T, Lo EH. Involvement of matrix metalloproteinase in thrombolysis-associated hemorrhagic transformation after embolic focal ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2002;33:831–836. doi: 10.1161/hs0302.104542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asahi M, Asahi K, Wang X, Lo EH. Reduction of tissue plasminogen activator-induced hemorrhage and brain injury by free radical spin trapping after embolic focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:452–457. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200003000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion: evaluation of the model and development of a neurologic examination. Stroke. 1986;17:472–476. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernandez TD, Schallert T. Seizures and recovery from experimental brain damage. Exp Neurol. 1998;102:318–324. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(88)90226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Chen J, Wang L, Lu M, Chopp M. Treatment of stroke in rat with intracarotid administration of marrow stromal cells. Neurology. 2001;56:1666–1672. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin R, Xiao AY, Chen R, Granger DN, Li G. Inhibition of CD147 (Cluster of Differentiation 147) ameliorates acute ischemic stroke in mice by reducing thromboinflammation. Stroke. 2017;48:3356–3365. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kastrup A, Gröschel K, Ringer TM, Redecker C, Cordesmeyer R, Witte OW, et al. Early disruption of the blood-brain barrier after thrombolytic therapy predicts hemorrhage in patients with acute stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:2385–2387. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang X, Tsuji K, Lee SR, Ning M, Furie KL, Buchan AM, et al. Mechanisms of hemorrhagic transformation after tissue plasminogen activator reperfusion therapy for ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:2726–2730. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000143219.16695.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Yemisci M, Dalkara T. Microvascular protection is essential for successful neuroprotection in stroke. J Neurochem. 2012;123(Suppl 2):2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao BQ, Wang S, Kim HY, Storrie H, Rosen BR, Mooney DJ, et al. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed cortical responses after stroke. Nat Med. 2006;12:441–445. doi: 10.1038/nm1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fluri F, Schuhmann MK, Kleinschnitz C. Animal models of ischemic stroke and their application in clinical research. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3445–3454. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S56071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L, Chopp M, Jia L, Cui Y, Lu M, Zhang ZG. Atorvastatin extends the therapeutic window for tPA to 6 h after the onset of embolic stroke in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1816–1824. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murata Y, Rosell A, Scannevin RH, Rhodes KJ, Wang X, Lo EH. Extension of the thrombolytic time window with minocycline in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:3372–3377. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang L, Zhang ZG, Zhang RL, Lu M, Adams J, Elliott PJ, Chopp M. Postischemic (6-hour) treatment with recombinant human tissue plasminogen activator and proteasome inhibitor ps-519 reduces infarction in a rat model of embolic focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2001;32:2926–2931. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.100207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kano T, Katayama Y, Tejima E, Lo EH. Hemorrhagic transformation after fibrinolytic therapy with tissue plasminogen activator in a rat thromboembolic model of stroke. Brain Res. 2000;854:245–248. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Lee SR, Arai K, Lee SR, Tsuji K, Rebeck GW, et al. Lipoprotein receptor-mediated induction of matrix metalloproteinase by tissue plasminogen activator. Nat Med. 2003;9:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/nm926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yepes M, Sandkvist M, Moore EG, Bugge TH, Strickland DK, Lawrence DA. Tissue-type plasminogen activator induces opening of the blood-brain barrier via the LDL receptor-related protein. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1533–1540. doi: 10.1172/JCI19212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu X, Song Z, Zhang S, Nanda A, Li G. CD147: a novel modulator of inflammatory and immune disorders. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:2138–2145. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666131227163352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Silva DA, Fink JN, Christensen S, Ebinger M, Bladin C, Levi CR, et al. Assessing reperfusion and recanalization as markers of clinical outcomes after intravenous thrombolysis in the echoplanar imaging thrombolytic evaluation trial (EPITHET) Stroke. 2009;40:2872–2874. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.543595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexandrov AV, Hall CE, Labiche LA, Wojner AW, Grotta JC. Ischemic stunning of the brain: early recanalization without immediate clinical improvement in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:449–452. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000113737.58014.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Desilles JP, Loyau S, Syvannarath V, Gonzalez-Valcarcel J, Cantier M, Louedec L, et al. Alteplase reduces downstream microvascular thrombosis and improves the benefit of large artery recanalization in stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:3241–3248. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harari OA, Liao JK. NF-κB and innate immunity in ischemic stroke. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1207:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang ZG, Chopp M, Goussev A, Lu D, Morris D, Tsang W, et al. Cerebral microvascular obstruction by fibrin is associated with upregulation of PAI-1 acutely after onset of focal embolic ischemia in rats. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10898–10907. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-24-10898.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seizer P, Borst O, Langer HF, Bültmann A, Münch G, Herouy Y, et al. EMMPRIN (CD147) is a novel receptor for platelet GPVI and mediates platelet rolling via GPVI-EMMPRIN interaction. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:682–686. doi: 10.1160/th08-06-0368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seizer P, Ungern-Sternberg SN, Schönberger T, Borst O, Münzer P, Schmidt EM, et al. Extracellular cyclophilin A activates platelets via EMMPRIN (CD147) and PI3K/Akt signaling, which promotes platelet adhesion and thrombus formation in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:655–663. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.305112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, et al. STAIR Group. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke. 2009;40:2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.