Abstract

Background

Transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA), often used to sample lymph nodes for lung cancer staging, is subject to sampling error even when performed with endobronchial ultrasound. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a high-resolution imaging modality that rapidly generates helical cross-sectional images. We aim to determine if needle-based OCT can provide microstructural information in lymph nodes that may be used to guide TBNA, and improve sampling error.

Methods

We performed ex vivo needle-based OCT on thoracic lymph nodes from patients with and without known lung cancer. OCT imaging features were compared against matched histology.

Results

OCT imaging was performed in 26 thoracic lymph nodes, including 6 lymph nodes containing metastatic carcinoma. OCT visualized lymphoid follicles, adipose tissue, pigment-laden histiocytes, and blood vessels. OCT features of metastatic carcinoma were distinct from benign lymph nodes, with microarchitectural features that reflected the morphology of the carcinoma subtype. OCT was also able to distinguish lymph node from adjacent airway wall.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that OCT provides critical microstructural information that may be useful to guide TBNA lymph node sampling, as a complement to endobronchial ultrasound. In vivo studies are needed to further evaluate the clinical utility of OCT in thoracic lymph node assessment.

Keywords: Bronchoscopic optical imaging, Optical frequency domain imaging, Biopsy guidance, Lung cancer staging, Transbronchial needle aspiration

Introduction

Intrathoracic lymph node evaluation plays a critical role in lung cancer staging, and subsequent therapeutic strategy [1]. Patients with non-small cell lung cancer metastatic to mediastinal lymph nodes are offered chemotherapy with or without the addition of radiation and/or surgery, whereas patients without mediastinal lymph node involvement typically undergo surgical resection as the first line of treatment. Lymph node evaluation usually begins with non-invasive imaging modalities, such as computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) [2, 3]. Histologic examination is the standard of care in the assessment of lymph node metastasis, and necessitates tissue sampling. Transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) of enlarged and/or PET positive nodes is a very common clinical approach for initial lymph node assessment in lung cancer patients and has high specificity, but this technique is subject to sampling error with sensitivity ranging from 0.5–0.7 [4]. Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) has been shown to be a highly impactful biopsy guidance tool in the evaluation of lymph nodes with TBNA, with reported sensitivities of 87% [4–6]. However, there are still false negative cases due to sampling error [4–6].

Rapid On-Site Evaluation (ROSE) of TBNA cytology has been implemented by many to help alleviate this problem. Although an effective technique, ROSE is a retrospective assessment of collected cytology, and therefore, still has false negative cases due to biopsy sampling error. ROSE can also be time consuming and costly, as often multiple passes need to be assessed and an on-call pathologist is required for assessments [7]. Additionally, tumor yield is important in the clinical context of node-positive lung cancer as this often is the only source of tumor, and sufficient volumes are needed for both diagnostic purposes and molecular testing. Unfortunately, ROSE cannot determine if adequate amounts of tumor have been collected for all diagnostic tests. The ability to assess lymph node tissue with microscopic resolution prior to tissue collection could guide sampling towards regions of pathology, when present, which could improve sampling error and increase tumor volume yield as a complement to ROSE.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a non-contact high-resolution imaging tool that provides information about tissue microstructure. OCT uses near infrared light to generate cross-sectional images with resolutions of < 10 µm, and penetration depths of approximately 2–3 mm in tissue [8–9]. Numerous applications of OCT have been described in pulmonary medicine, including the use of OCT for biopsy guidance [10–24]. Needle-based OCT catheters have been developed by many groups [24–31]. Tan et. al developed a thin, flexible needle-based OCT imaging catheter that is compatible with standard bronchoscopy TBNA needles, and allows for OCT imaging and tissue collection with the same needle [24]. The ability to distinguish airway wall and lung parenchyma from lung nodules with OCT has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity, and could increase diagnostic yield by confirming placement of the biopsy needle and guiding optimal site selection for tissue acquisition [13, 24].

Needle-based OCT imaging performed during TBNA has potential to play an important role in the evaluation of thoracic lymph nodes. OCT could provide intraprocedural microscopic assessment to aid the bronchoscopist in targeting abnormal appearing lymph node regions for tissue sampling, which could reduce sampling error and improve diagnostic yield. Other groups have assessed benchtop in-air OCT imaging of ex vivo axillary lymph nodes in breast cancer [32–37]. However, studies have not been performed to assess catheter-based or needle-based OCT in lymph nodes, and therefore, feasibility for in vivo OCT biopsy guidance has not been assessed. In this manuscript, we perform needle-based OCT imaging of human thoracic lymph nodes to assess the potential for intraprocedural lymph node biopsy guidance to increase diagnostic yield. We utilize needle-based OCT to describe and compare morphological OCT features of benign thoracic lymph nodes against those harboring metastatic carcinoma, and identify OCT imaging characteristics that may predict pathology, and guide selection of the optimum biopsy site during TBNA to increase diagnostic yield.

Materials and Methods

OCT Imaging

This study was approved by the Partners Human Research Committee Institutional Review Board (protocol number 2010P0002214). Intact thoracic lymph nodes, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin solution, were harvested from autopsy and surgical resection specimens obtained from patients with and without known lung cancer. Lymph nodes were imaged ex vivo using an OCT needle probe. The details of the catheter design have been previously reported [24]. Briefly, the OCT catheter consists of an imaging core housed inside a transparent polyimide sheath. The imaging core consists of an optical fiber, distal focusing elements, and a nitinol drive shaft. In order to gain access to the lymph node, an OCT catheter was inserted through a standard 18-gauge needle, which was used to transverse the lymph node. The needle was then retracted, leaving the OCT catheter within the lymph node. Whenever possible, OCT imaging was conducted along needle tracts that traverse both the airway wall and adjacent lymph node. The imaging core was pulled back at a rate of 0.25 mm/second and OCT imaging was acquired at a rate of 33 frames per second (frame size: 2248 × 2048) along the long axis of the needle tract. After imaging, the needle was re-advanced over the OCT catheter along the imaged track, and tissue ink was used to mark the OCT imaging region for subsequent registration with histology.

Histology Processing

Following OCT imaging, lymph nodes were bisected along the needle tract, and submitted for histologic processing, sectioning, and staining. Histology sections were cut to traverse the needle tract for registration with OCT imaging, and stained with Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E). The prepared histology slides were subsequently digitized using a whole slide scanner (NanoZoomer RS, Hamamatsu; Hamamatsu City, Japan).

OCT Imaging Processing

The volumetric OCT datasets were imported into ImageJ 1.38w (National Institutes of Health) for processing and registration to the digitized histology slides. OCT image stacks were scaled and resliced to generate longitudinal slices corresponding to histology. All OCT images were displayed using a grayscale lookup table.

Image Interpretation

The OCT images were assessed in conjunction with the corresponding histology slides by the research team, which included two pulmonologists, one OCT expert, and one pathologist with expertise in OCT imaging. Image interpretation criteria were developed based on architectural features visible in both the OCT and corresponding histology.

Results

A total of 31 volumetric OCT datasets were obtained from 26 human thoracic lymph nodes: 20 benign lymph nodes, including normal, reactive, and anthracotic (pigment-laden) lymph nodes, and 6 lymph nodes containing metastatic carcinoma. Metastatic adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) were present in two and four lymph nodes, respectively. Multiple sites within a single large lymph node were imaged if the sites were spatially distinct. Mean lymph node dimensions were 1.6 cm × 1.2 cm and 2.1 cm × 1.5 cm for benign and malignant lymph nodes, respectively.

Normal/Benign Lymph Nodes

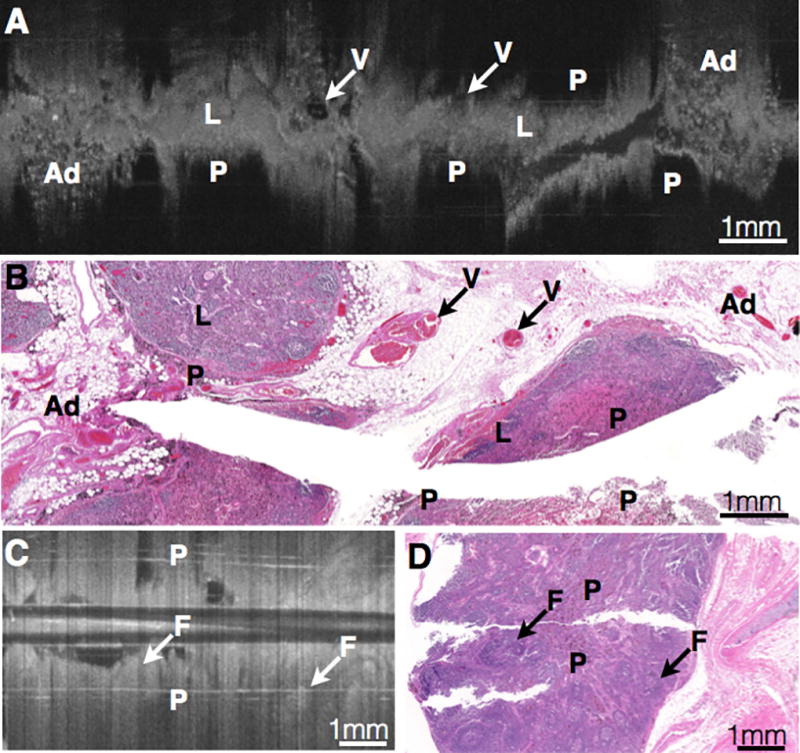

OCT imaging of benign lymph nodes revealed distinct patterns of architecture that reflected the features seen in corresponding histology (Figure 1). Regions with lymphocytes appear homogeneous with moderate signal intensity and minimal microarchitectural variation. Lymphoid follicles are seen as evenly round structures with moderate signal intensity and ill-defined borders. In reactive lymph nodes, lymphoid follicles are more numerous, and more likely to contain germinal centers that appear as signal-void regions within follicles. Histiocytes containing anthracotic pigment are commonly present within thoracic lymph nodes, and appear on OCT as regions with rapid signal attenuation containing minute, high signal intensity punctate structures. Perinodal adipose tissue is visualized on OCT as aggregates of small, evenly round signal-void structures with thin, signal-intense walls resembling a “soap bubble” appearance. Hilar vessels appear as rounded structures with a central lumen when imaged on cross-section, and as a cylindrical or serpentine structure with a central lumen when imaged longitudinally.

Figure 1. Needle-based OCT imaging (A, C) and corresponding histology (B, D) of benign thoracic lymph nodes.

Regions with lymphocytes (L) appear homogeneous with moderate signal intensity and minimal microarchitectural variation. Lymphoid follicles (F) are seen as round, homogeneous structures with moderate signal intensity and ill-defined borders. Histiocytes containing anthracotic pigment (P) appear as regions with very rapid signal attenuation containing minute, high signal intensity punctate structures (P). Perinodal adipose tissue (Ad) is visualized on OCT as aggregates of small, evenly round signal-void structures with thin, signal-intense walls resembling a “soap bubble” appearance. Hilar vessels (V) appear as rounded structures with a central lumen when imaged on cross-section, and as a cylindrical or serpentine structure with a central lumen when imaged longitudinally (V). Scalebars: 1 mm.

Malignant Lymph Nodes

Metastatic carcinoma within lymph nodes has a more heterogeneous appearance than benign lymph node tissue, with irregular architecture and variations in signal intensity and attenuation. Squamous cell carcinoma within the lymph nodes appears on OCT as irregularly shaped, signal-intense nests (Figure 2). SCC nests containing central necrosis on histology appear as nested structures with a signal-intense periphery and central signal-poor homogeneous tissue that corresponds to the necrotic region. When compared with lymphoid follicles, nests of SCC have a more irregular shape and well-defined borders. Metastatic adenocarcinoma in the lymph node appears as regions containing round or angulated signal-poor structures, and lacks the irregular signal-intense nests seen in SCC (Figure 3). A summary of the OCT imaging findings for benign and malignant lymph nodes is presented in Table 1.

Figure 2. Needle-based OCT imaging (A) and histology (B) of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in lymph node.

Metastatic carcinoma within lymph nodes is more heterogeneous in appearance than benign lymph node tissue, with irregular architecture and variations in signal intensity and attenuation. Squamous cell carcinoma within the lymph nodes appears on OCT as irregularly shaped, signal intense nests (N). SCC nests containing central necrosis on histology appear as nested structures with a signal intense periphery and central signal-poor homogeneous tissue that corresponds to the necrotic region. When compared with lymphoid follicles, nests of SCC have a more irregular shape and well-defined borders. Perinodal adipose tissue (Ad) can also be seen on OCT. Scalebars: 1 mm.

Figure 3. Needle-based OCT imaging (A) and histology (B) of metastatic adenocarcinoma in lymph node through airway wall.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma in the lymph node appears as regions containing round or angulated signal poor gland-like structures (G), and lacks the irregular signal intense nests seen in SCC. Bronchoscopic needle-based tissue sampling of thoracic lymph nodes traverses airways to access lymph nodes beyond the airway wall. In this example, needle-based OCT imaging traverses both the airway wall (Airway) and adjacent lymph node (LN), and demonstrates visualization of the layered airway wall architecture, including the epithelium (E), lamina propria (LP), and cartilaginous rings C). The airway wall is morphologically distinct from the adjacent lymph node. The histology for this sample suffered some artifacts from processing and sectioning, however, the histological features are identifiable. Scalebars: 1 mm.

Table 1.

Summary of Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging Features in Thoracic Lymph Nodes.

| Histological Feature | OCT Imaging Feature | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Normal LN | ||

|

| ||

| Lymphoid tissue | Homogeneous regions of tissue with moderate signal intensity and minimal microarchitectural variation | |

|

| ||

| Follicles | Round, homogeneous structures with moderate signal intensity | |

|

| ||

| Anthracotic pigment | Regions of very rapid signal loss containing minute, punctate structures with high signal intensity | |

|

| ||

| Vessels | Rounded structures with lumen, either circular if in cross-section or cylindrical/serpentine if longitudinally sectioned | |

|

| ||

| Perinodal adipose tissue | Small, round signal void structures with thin bright signal intense wall | |

| Often structures are aggregated in close proximity | ||

|

| ||

| Adjacent bronchial wall | Structure with layered architecture that can contain the following:

|

|

|

| ||

| Metastasis | ||

|

| ||

| SCC | Irregularly shaped signal intense nests with well-defined borders | |

| May contain regions of homogenous, signal poor necrosis either within nests or admixed with nests | ||

|

| ||

| Adenocarcinoma | Round to angulated signal poor structures | |

| Lack of signal intense nests | ||

Transbronchial Imaging of Lymph Nodes

Transbronchial tissue sampling of lymph nodes requires the needle to traverse an airway in order to access a lymph node beyond the airway wall. OCT imaging along needle tracts that traverse both the airway wall and adjacent lymph node (Figure 3) demonstrates visualization of the layered airway wall architecture, including the epithelium, lamina propria, and cartilaginous rings. The airway wall on OCT imaging is morphologically distinct from the adjacent lymph node in both benign lymph nodes and those containing metastatic carcinoma.

Discussion

Bronchoscopic TBNA, a common technique used to sample lymph node tissue as part of lung cancer staging, can suffer from sampling error even when guidance techniques, such as EBUS, are employed. In this study, we conducted OCT imaging of human thoracic lymph nodes, and demonstrated that needle-based OCT can provide information about lymph node microarchitecture that could be used for intraprocedural TBNA sampling site guidance during lung cancer staging. We demonstrated that OCT imaging features of normal/benign lymph nodes, such as lymphoid follicles, macrophages, and adipose tissue, are identifiable and distinct from OCT imaging features of metastatic carcinoma in lymph nodes. We also investigated OCT imaging of features unique to thoracic lymph nodes, such as the need to traverse an airway to gain access to these nodes, and the presence of pigment-laden macrophages. This is an essential first step in the translation of OCT technology to clinical use as part of thoracic lymph node assessment and biopsy guidance. Microstructural needle-based OCT imaging has potential to play an important complementary role in the evaluation of thoracic lymph nodes, specifically to guide intraprocedural selection of optimal biopsy site in real time and potentially increase diagnostic yield [13]. OCT also has potential to aid in guiding biopsy sampling in other lymph node locations, such as cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes.

OCT imaging features of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma, such as regions of hyper-intense signal with signal poor central necrosis, and adenocarcinoma, such as areas of round/angulated signal poor glandular structures, are consistent with the OCT imaging characteristics of primary lung SCC and adenocarcinoma described by Hariri et al [12, 14]. It is possible that OCT may also be useful to help avoid biopsy of necrotic and/or fibrotic tissues frequently associated with carcinoma, as demonstrated in prior work by our group [13]. The tumor foci in this study were not microscopic. Future studies will be needed to assess lymph nodes with microscopic tumor foci to further investigate the usefulness of OCT in this setting. Given that OCT provides rapid 3D imaging of tissue volumes significantly larger than the needle sampling volume, we anticipate that combined EBUS and OCT guidance may provide an improved diagnostic yield over EBUS-guided sampling alone in these cases.

Although implementation of ROSE is an effective method to assess TBNA cytology, it is a retrospective assessment of collected material rather than a prospective assessment of biopsy site [7]. This can result in lengthy and costly procedures, as often multiple passes must be assessed to ensure diagnostic material is present, with an on-site pathologist on stand-by in between passes. Needle-based OCT could complement ROSE by providing prospective in vivo guidance of biopsy site selection with microscopic resolution, and therefore, reducing the number of passes requiring ROSE.

During TBNA, inadvertent biopsy of airway wall components can contaminate tissue samples and compromise diagnostic yield. We observed that OCT was able to distinguish airway wall, including individual airway wall layers, from adjacent lymph node tissue. This ability has potential to help guide needle localization to the targeted lymph node and minimize inadvertent airway wall sampling, which would be especially beneficial in the setting of small lymph nodes.

Anthracotic pigment from smoking or environmental exposure is frequently encountered in thoracic lymph nodes, but is typically absent in lymph nodes outside the thorax. We demonstrated that the presence of anthracotic pigment within lymph nodes resulted in increased light scattering and reduced penetration on OCT. Studies have shown that the presence of microscopic anthracotic pigmentation in thoracic lymph nodes is significantly associated with benign pathology [38]. Although this pigment results in reduced penetration depth, its presence may be a useful OCT imaging characteristic as an indicator of benign lymph node tissue, which would be beneficial information in guiding biopsy site selection. If it is determined that the reduced penetration limits adequate intraprocedural assessment, the needle could be repositioned to obtain additional OCT data. Further studies will be performed to assess the usefulness and/or limitations of anthracotic pigment in OCT guidance of lymph node sampling.

In addition to the 18-gauge needle-based OCT probe used in this study, we have also developed 19-gauge and 21-gauge needle-based OCT probes, all of which are compatible with commercially available TBNA needles. We have conducted studies assessing the performance of our needle-based OCT probes at various bends, to simulate potential in vivo bronchoscopic situations, and found that imaging was achievable without significant imaging artifacts even with a sharp 90 degree turn at the distal probe end [39].

We performed this study in the ex vivo setting in order to obtain one-to-one matched histology for precise, accurate OCT criteria development, which is not achievable in the in vivo setting. However, there are several important factors that must be considered with ex vivo imaging. Tissue degradation after excision may impact tissue quality, and therefore, image quality. The histology examined on all our tissues showed no appreciable signs of degradation. Due to the need to complete pathologic evaluation for clinical purposes, the lymph nodes imaged in this study were fixed in 10% formalin prior to OCT imaging. However, studies have been performed comparing OCT imaging of fixed versus fresh tissues, and have demonstrated that fixation does not introduce significant differences in optical properties in OCT [40]. Therefore, we do not anticipate that the formalin fixation affected image quality.

In this study, we describe needle-based OCT imaging characteristics of both benign thoracic lymph nodes and those harboring metastatic lung carcinoma, which demonstrate the potential of OCT as an intraprocedural guidance method for TBNA. However, future large-scale studies are required to assess the sensitivity and specificity of the OCT imaging features, as well as to assess the ability to detect microscopic foci of metastatic carcinoma. Additionally, studies assessing the in vivo translation of needle-based OCT for TBNA lymph node biopsy guidance will need to be performed to assess the true clinical impact.

Translation to the in vivo setting may result in potential limitations not encountered ex vivo. Bleeding, known to occur in the setting of multiple TBNA passes, may result in loss of optical signal quality. However, the vessels that are the source of the bleeding are primarily located within the airway wall, rather than within the lymph node. Lymph nodes contain high numbers of lymphatic vessels, which do not contain blood cells that scatter OCT incident light and obstruct the field of view. Additionally, in the setting of needle-based OCT guidance, imaging would precede tissue collection. Even if multiple OCT imaging tracks are required to find an ideal site for biopsy, the repeat advances into the tissue would be to place a needle for imaging, rather than to repeatedly apply suction and agitate tissue to collect cells for pathology assessment. Due to these aspects, we anticipate that small volume saline flush would be adequate to remove any blood contamination, which has been highly effective even in the setting of coronary artery imaging. We have conducted preliminary in vivo studies assessing needle-based OCT in swine animal models, and did not encounter difficulties with bleeding obstructing the OCT field of view. Accumulation of airway secretions may lead to distorted airway images, but suction can be employed to remove mucus and other secretions. Image artifacts related to motion from cough, as well as cardiac and respiratory motion may occur. Acquisition of in vivo OCT data using rapid frame rates has been shown to allow for successful visualization of fine imaging features in the lung in numerous published studies [14–24]. In addition, placement of the needle within the lymph node will likely serve to stabilize the OCT catheter within the tissue, and mitigate motion artifacts.

Conclusion

In this study, we demonstrate feasibility for needle-based OCT of thoracic lymph nodes, with pathologist interpretation of OCT images, which is an essential first step towards translating the technology to intraprocedural clinical use. We assessed OCT imaging characteristics of benign and malignant human thoracic lymph nodes as compared with histology. Our results suggest that benign lymph nodes and lymph nodes with metastatic carcinoma have distinct OCT imaging features that could potentially be useful to guide clinical TBNA lymph node sampling. Although not a substitute for histologic examination, identification of characteristic findings on OCT imaging may guide the selection of optimum biopsy site, which could reduce sampling error, increase diagnostic yield, and provide clues about histologic diagnosis. However, larger studies are required to validate OCT imaging characteristics in lymph node assessment, including training physicians on OCT interpretation, to determine sensitivity and specificity. We have already successfully conducted similar studies evaluating OCT for the assessment and diagnosis of primary lung carcinomas, including carcinoma subtype, and demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity [10, 12].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Wellman Center for Photomedicine Photopathology core at Massachusetts General Hospital for their contributions to this work.

This work was funded in part by the National Institute of Heath [Grant numbers R01CA167827, T32CA009216], and a grant from the LUNGevity Foundation/Upstage Lung Cancer [Grant number 2016-02].

Abbreviations

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- TBNA

transbronchial needle aspiration

- CT

computed tomography

- PET

positron emission tomography

- EBUS

endobronchial ultrasound

- H&E

Hematoxylin & Eosin

- SCC

squamous cell carcinoma

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Eugene Shostak: No conflicts of interest.

Dr. Lida Hariri: Dr. Hariri is an author on a Massachusetts General Hospital owned patent that has been licensed to LX Medical. Dr. Hariri has the rights to receive royalties from this licensing arrangement. Dr. Hariri is a consultant for LX Medical.

Dr. George Z. Cheng: No conflicts of interest.

Dr. David C. Adams: No conflicts of interest.

Dr. Melissa Suter: Dr. Suter is an author on Massachusetts General Hospital owned patents that have been licensed to NinePoint Medical, and LX Medical. Dr. Suter has the rights to receive royalties from these licensing arrangements. Dr. Suter was a past consultant for NinePoint Medical, and is a consultant for LX Medical.

Author contributions:

Drs. Shostak and Hariri: contributed to the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and reading and approving the final version.

Dr. Cheng and Adams: contributed to the collection and analysis of data; critical review of the manuscript; and reading and approving the final version.

Dr. Suter: contributed to the study design; development of the imaging system and catheters; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; drafting and critical review of the manuscript; and reading and approving the final version. Dr. Suter had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chin R, Jr, Ward R, Keyes JW, Choplin RH, Reed JC, Wallenhaupt S, et al. Mediastinal staging of non-small-cell lung cancer with positron emission tomography. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1995;152(6 Pt 1):2090–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLoud TC, Bourgouin PM, Greenberg RW, Kosiuk JP, Templeton PA, Shepard JA, et al. Bronchogenic carcinoma: analysis of staging in the mediastinum with CT by correlative lymph node mapping and sampling. Radiology. 1992;182(2):319–23. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.2.1732943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kramer H, Groen HJ. Current concepts in the mediastinal lymph node staging of nonsmall cell lung cancer. Ann Surg. 2003;238(2):180–8. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000081086.37779.1a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bugalho A, Ferreira D, Eberhardt R, Dias SS, Videira PA, Herth FJ, et al. Diagnostic value of endobronchial and endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration for accessible lung cancer lesions after non-diagnostic conventional techniques: a prospective study. BMC cancer. 2013;13:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Memoli JS, El-Bayoumi E, Pastis NJ, Tanner NT, Gomez M, Huggins JT, et al. Using endobronchial ultrasound features to predict lymph node metastasis in patients with lung cancer. Chest. 2011;140(6):1550–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Cunha Santos G, Ko HM, Saieg MA, Geddie WR. "The petals and thorns" of ROSE (rapid on-site evaluation) Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121(1):4–8. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254(5035):1178–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1957169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yun S, Tearney G, de Boer J, Iftimia N, Bouma B. High-speed optical frequency-domain imaging. Optics express. 2003;11(22):2953–63. doi: 10.1364/oe.11.002953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hariri LP, Mino-Kenudson M, Applegate MB, Mark EJ, Tearney GJ, Lanuti M, et al. Toward the guidance of transbronchial biopsy: identifying pulmonary nodules with optical coherence tomography. Chest. 2013;144(4):1261–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hariri LP, Mino-Kenudson M, Mark EJ, Suter MJ. In vivo optical coherence tomography: the role of the pathologist. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(12):1492–501. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0252-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hariri LP, Mino-Kenudson M, Lanuti M, Miller AJ, Mark EJ, Suter MJ. Diagnosing lung carcinomas with optical coherence tomography. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2015;12(2):193–201. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201408-370OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hariri LP, Villiger M, Applegate MB, Mino-Kenudson M, Mark EJ, Bouma BE, et al. Seeing beyond the bronchoscope to increase the diagnostic yield of bronchoscopic biopsy. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;187(2):125–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1483OE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hariri LP, Applegate MB, Mino-Kenudson M, Mark EJ, Medoff BD, Luster AD, et al. Volumetric optical frequency domain imaging of pulmonary pathology with precise correlation to histopathology. Chest. 2013;143(1):64–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuboi M, Hayashi A, Ikeda N, Honda H, Kato Y, Ichinose S, et al. Optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis of bronchial lesions. Lung Cancer. 2005;49(3):387–94. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam S, Standish B, Baldwin C, McWilliams A, leRiche J, Gazdar A, et al. In vivo optical coherence tomography imaging of preinvasive bronchial lesions. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008;14(7):2006–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hou R, Le T, Murgu SD, Chen Z, Brenner M. Recent advances in optical coherence tomography for the diagnoses of lung disorders. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5(5):711–24. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coxson HO, Lam S. Quantitative assessment of the airway wall using computed tomography and optical coherence tomography. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2009;6(5):439–43. doi: 10.1513/pats.200904-015AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coxson HO, Quiney B, Sin DD, Xing L, McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, et al. Airway wall thickness assessed using computed tomography and optical coherence tomography. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2008;177(11):1201–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1776OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michel RG, Kinasewitz GT, Fung KM, Keddissi JI. Optical coherence tomography as an adjunct to flexible bronchoscopy in the diagnosis of lung cancer: a pilot study. Chest. 2010;138(4):984–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whiteman SC, Yang Y, Gey van Pittius D, Stephens M, Parmer J, Spiteri MA. Optical coherence tomography: real-time imaging of bronchial airways microstructure and detection of inflammatory/neoplastic morphologic changes. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2006;12(3 Pt 1):813–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson JP, McLaughlin RA, Phillips MJ, Armstrong JJ, Becker S, Walsh JH, et al. Using optical coherence tomography to improve diagnostic and therapeutic bronchoscopy. Chest. 2009;136(1):272–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McLaughlin RA, Noble PB, Sampson DD. Optical coherence tomography in respiratory science and medicine: from airways to alveoli. Physiology (Bethesda) 2014;29(5):369–80. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00002.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan KM, Shishkov M, Chee A, Applegate MB, Bouma BE, Suter MJ. Flexible transbronchial optical frequency domain imaging smart needle for biopsy guidance. Biomedical optics express. 2012;3(8):1947–54. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.001947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang CP, Wierwille J, Moreira T, Schwartzbauer G, Jafri MS, Tang CM, et al. A forward-imaging needle-type OCT probe for image guided stereotactic procedures. Optics express. 2011;19(27):26283–94. doi: 10.1364/OE.19.026283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenser D, Yang X, Kirk RW, Quirk BC, McLaughlin RA, Sampson DD. Ultrathin side-viewing needle probe for optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2011;36(19):3894–6. doi: 10.1364/OL.36.003894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Chudoba C, Ko T, Pitris C, Fujimoto JG. Imaging needle for optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2000;25(20):1520–2. doi: 10.1364/ol.25.001520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu Y, Xi J, Huo L, Padvorac J, Shin EJ, Giday SA, et al. Robust high-resolution fine OCT needle for side-viewing interstitial tissue imaging. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics. 2010;16(4):863–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scolaro L, Lorenser D, McLaughlin RA, Quirk BC, Kirk RW, Sampson DD. High-sensitivity anastigmatic imaging needle for optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2012;37(24):5247–9. doi: 10.1364/OL.37.005247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang VXD, Mao YX, Munce N, Standish B, Kucharczyk W, Marcon NE, et al. Interstitial Doppler optical coherence tomography. Optics Letters. 2005;30(14):1791–3. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.001791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuo W, Kim J, Shemonski ND, Chaney EJ, Spillman DR, Boppart SA. Real-time three-dimensional optical coherence tomography image-guided core-needle biopsy system. Biomedical optics express. 2012;3(6):1149–61. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luo W, Nguyen FT, Zysk AM, Ralston TS, Brockenbrough J, Marks DL, et al. Optical biopsy of lymph node morphology using optical coherence tomography. Technology in cancer research & treatment. 2005;4(5):539–48. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen FT, Zysk AM, Chaney EJ, Adie SG, Kotynek JG, Oliphant UJ, et al. Optical coherence tomography: the intraoperative assessment of lymph nodes in breast cancer. IEEE engineering in medicine and biology magazine : the quarterly magazine of the Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society. 2010;29(2):63–70. doi: 10.1109/MEMB.2009.935722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scolaro L, McLaughlin RA, Klyen BR, Wood BA, Robbins PD, Saunders CM, et al. Parametric imaging of the local attenuation coefficient in human axillary lymph nodes assessed using optical coherence tomography. Biomedical optics express. 2012;3(2):366–79. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.000366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin RA, Scolaro L, Robbins P, Hamza S, Saunders C, Sampson DD. Imaging of human lymph nodes using optical coherence tomography: potential for staging cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70(7):2579–84. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nolan RM, Adie SG, Marjanovic M, Chaney EJ, South FA, Monroy GL, et al. Intraoperative optical coherence tomography for assessing human lymph nodes for metastatic cancer. BMC cancer. 2016;16:144. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2194-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.John R, Adie SG, Chaney EJ, Marjanovic M, Tangella KV, Boppart SA. Three-dimensional optical coherence tomography for optical biopsy of lymph nodes and assessment of metastatic disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(11):3685–93. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2434-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park YS, Lee J, Pang JC, Chung DH, Lee SM, Yim JJ, et al. Clinical implication of microscopic anthracotic pigment in mediastinal staging of non-small cell lung cancer by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Journal of Korean medical science. 2013;28(4):550–4. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.4.550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holz JA, Shishkov M, Wang Y, Adams DC, Hariri LP, Channick CL, et al., editors. Flexible optical coherence tomography catheter for transbronchial imaging SPIE Photonics West Endoscopic Microscopy XII; Optical Techniques in Pulmonary Medicine IV. San Francisco, CA: SPIE Proceedings; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gnanadesigan M, van Soest G, White S, Scoltock S, Ughi GJ, Baumbach A, et al. Effect of temperature and fixation on the optical properties of atherosclerotic tissue: a validation study of an ex-vivo whole heart cadaveric model. Biomedical optics express. 2014;5(4):1038–49. doi: 10.1364/BOE.5.001038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]