Abstract

Background

A prime objective driving the recent development of human neural prosthetics is to stimulate neural circuits in a manner time-locked to ongoing brain activity. The human supplementary motor area (SMA) is a particularly useful target for this objective because it displays characteristic neural activity just prior to voluntary movement.

Objective

Here, we tested a method that detected activity in the human SMA related to impending movement and then delivered cortical stimulation with intracranial electrodes to influence the timing of movement.

Methods

We conducted experiments in nine patients with electrodes implanted for epilepsy localization: five patients with SMA electrodes and four control patients with electrodes outside the SMA. In the first experiment, electrocorticographic (ECoG) recordings were used to localize the electrode of interest during a task involving bimanual finger movements. In the second experiment, a real-time sense-and-stimulate (SAS) system was implemented that delivered an electrical stimulus when pre-movement gamma power exceeded a threshold.

Results

Stimulation based on real-time detection of this supra-threshold activity resulted in significant slowing of motor behavior in all of the cases where stimulation was carried out in the SMA patients but in none of the patients where stimulation was performed at the control site.

Conclusions

The neurophysiological correlates of impending movement can be used to trigger a closed loop stimulation device and influence ongoing motor behavior in a manner imperceptible to the subject. This is the first report of a human closed loop system designed to alter movement using direct cortical recordings and direct stimulation.

Keywords: ECoG, closed-loop, Supplementary motor area

Introduction

An aspirational goal in the development of human neural prosthetics is to deliver focal stimulation to neural circuits in a manner informed by ongoing brain activity. Such real-time ‘sense-and stimulate’ (SAS) or ‘closed-loop’ neuromodulation has potential for therapeutic value in a broad range of conditions including movement disorders [1, 2], neuropsychiatric disorders [3], and for critically assessing hypotheses about neural systems [4]. SAS is still in its infancy, with only a few demonstrations of possible proof of concept. For scalp EEG, activity has been used to trigger transcranial magnetic [5, 6] or direct current stimulation [7, 8]. However, scalp recordings are limited by the spatial specificity of the recordings and by the spatial specificity of the corresponding kinds of noninvasive brain stimulation (especially in the case of transcranial direct current stimulation). Local field potentials recorded from the basal nuclei have been used to trigger electrical stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus in Parkinson's disease [9, 10] but this was not done in the context of specific behaviors, therefore the effect on specific movements or circuit-specific effects could not be assessed. Long-term use of a commercial responsive neurostimulation system (RNS) designed to prevent partial onset seizures has been found to be safe and effective at reducing seizure frequency [11, 12].

Here, we developed and evaluated a cortical SAS system using ECoG during movement, recorded from the supplementary motor area (SMA). The SMA, located in the medial premotor cortex, is an especially good candidate for such an approach because activity in this area can be detected in local field potentials hundreds of milliseconds before movement [13-17]. This interval between neural activity and incipient motor behavior provides a window for detecting and processing brain changes and for triggering stimulation to affect motor behavior.

We developed a task that required subjects to move fingers of both hands in a sequence after a cue occurred. This kind of coordinated, sequenced, internally paced movement is known to activate the SMA and some other frontal regions robustly [18-20]. We studied nine patients with semi-chronically implanted intracranial electrodes that had been placed for the localization of seizures. We localized electrodes that showed prominent pre movement related activity in each of these individuals using an experiment that served as a functional localizer. Five electrodes were located in the SMA based on anatomical criteria and four were located outside of the SMA. We then developed a closed-loop SAS system to record cortical activity and to use it to trigger stimulation in real time. Our hypothesis was that this sense-and-stimulate approach of the SMA would delay the onset of motor behavior, and that this effect might not be notable in areas outside the SMA.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Nine adult patients (mean age = 27 ± 3 years, 6 female, all right hand dominant) undergoing invasive seizure recordings to localize pharmacologically intractable epilepsy volunteered to participate in the study. All participants provided informed consent according to a human subjects protocol of the McGovern Medical School ethics committee. Five patients had at least one electrode recording from the supplementary motor area, and four patients had electrodes outside the SMA. Two had electrode coverage in primary motor cortex (S2 & S3), one had electrode coverage anterior to pre-SMA (S1), and one had electrode coverage on the border of SMA and the paracentral lobule (S4). Electrodes were localized using the methods described below.

General Procedure

The experiment was conducted in two phases. In each phase, the patient performed a simple bimanually coordinated motor task (see below) while ECoG data were recorded. In Phase 1, the subject performed the task and post-hoc analysis of ECoG was done to identify contacts that showed clear pre-movement activity. In Phase 2 we used the closed-loop system to detect power changes in the high gamma frequency band (>60Hz) in real time, and when power exceeded a pre-defined threshold, the system triggered transient electrical stimulation of the electrodes that showed this activity. We supposed that, in the Phase 2 experiment, we would selectively affect movement, if stimulation occurred in the SMA, but not necessarily in regions outside the SMA.

Behavioral task

Patients were seated in front of a laptop computer with their hands on the keyboard. Six keys on the laptop keyboard (QWERTY layout) were labeled: the ‘F’ and ‘J’ keys were colored red and labeled ‘1’, the ‘D’ and ‘K’ keys were colored green and labeled ‘2’, and the ‘S’ and ‘L’ keys were colored blue and labeled ‘3’ (Figure 1). Patients were instructed to place their left and right index fingers on the red ‘1’ buttons, their middle fingers on the green ‘2’ buttons, and their ring fingers on the blue ‘3’ buttons. They were instructed to make a sequence of coordinated bimanual button presses at any time after the cue (i.e. not specifically immediately after the cue) following the appearance of the cue. At the beginning of each trial, a fixation cross appeared on the screen. After a random interval (2±0.34 s), an image appeared instructing the patient to perform either an ‘inward’ or an ‘outward’ button press sequence. Each condition was chosen randomly with equal likelihood on a trial-by-trial basis.

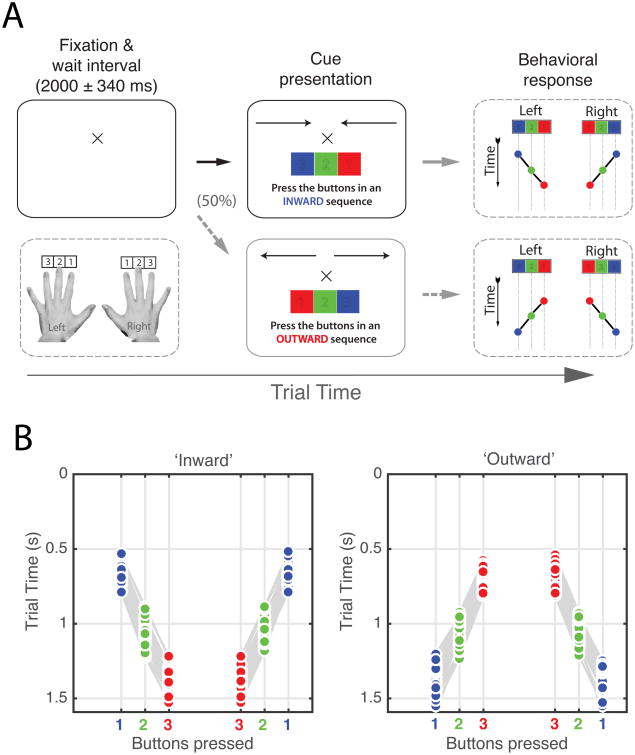

Figure 1.

Depiction of experimental task design. A, Patients were instructed to place their fingers on labeled keys and await instructions on the screen. On 50% of the trials, patients were instructed to press buttons in an ‘inward’ sequence starting with the ring fingers and followed by the middle and index fingers. In the other 50% of trials, patients were instructed to perform an ‘outward’ button press sequence, starting with the index fingers followed by the middle and ring fingers. Once an instruction cue appeared, the patients responded by pressing keys with each hand in the sequence indicated by the cue. Patients were allowed two seconds following the first button press to complete the sequence. Behavioral accuracy and reaction times were recorded for offline analysis. B, Behavioral results from one patient. Index finger button presses are shown in red. Middle and ring finger responses are shown in blue and green, respectively. A grey line connects single trial response sequences for each hand.

To complete the ‘inward’ sequence the patients simultaneously pressed the ‘3’ buttons, followed by the ‘2’ and ‘1’ buttons. This corresponded to a ring-middle-index finger movement pattern. The ‘outward’ sequence was a similar movement pattern, but in the opposite direction; buttons were pressed in a ‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’ sequence. This process was then repeated in blocks of 10 trials for a total of 80-120 trials. Patients were instructed to respond to the instruction cue promptly and accurately. Stimulus presentation and experimental control was accomplished using custom written PsychoPy Python scripts [21, 22].

Data acquisition and electrode selection

ECoG data were acquired from stereotactically placed depth electrodes implanted for clinical purposes using a Robotic Surgical Assistant (ROSA – Medtech, Montpellier, France). Each of these sEEG electrodes (PMT corporation, Chanhassen, Minnesota) was 0.8 mm in diameter and with 8-16 contacts. Each contact was a platinum-iridium cylinder, 2.0 mm in length and separated from the adjacent contact by 1.5-2.43 mm. Each patient had multiple (12-16) such electrodes implanted.

ECoG data were digitized at 2 kHz using the NeuroPort recording system (Blackrock Neuromed). ECoG signals recorded during the localizer phase of the experiment were initially referenced to an artificial zero, meaning that they represented the potentials recorded at each electrode rather than having an additional reference signal subtracted (e.g. common average or single electrode) [23]. ECoG data were subsequently referenced to a common average of all non-excluded electrodes. Epoched signals from the localizer task were used to generate an event-related spectral perturbation (ERSP) plot [24] at each electrode. These time-frequency plots were then used to identify contacts showing movement-related power spectrum changes.

The contact showing the strongest pre-movement increases in gamma frequency (∼60-180 Hz) was selected for online analysis in the closed-loop phase of the experiment. This was done independent of location in the brain, and the precise anatomical location of the electrode was determined post hoc as described below. Once this electrode was identified, two adjacent electrodes were designated as anode and cathode terminals for bipolar current injection [25]. We used a bipolar configuration in order to limit the region of stimulation to the area around the target electrode. Where possible, the two stimulation electrodes straddled the recording electrode. If this was impossible, for instance if the recording electrode was located at the tip of the recording probe, we used the next closest pair of electrodes on the same probe for stimulation. For consistency, anodes were always superficial (i.e. closer to the dura), to the cathodes. Finally, a single electrode was chosen to serve as a reference during online closed-loop analysis. This electrode was chosen based on the absence of interictal epileptiform discharges, movement-related activity, or excessive line noise. We chose to focus on detecting changes in gamma frequencies rather than lower frequencies (e.g. beta) because higher frequency oscillations can be observed and quantified faster than low frequencies. Similarly, we chose to use a single reference electrode rather than a common average in order to simplify and speed online decoding.

Electrode localization

Electrodes were localized using a procedure that involved registration of pre-operative anatomical MRI and post-operative CT scans. The pre-operative MRI was obtained using either a 1.5T or a 3T whole-body MR scanner and then coregistered to the post-operative CT. Electrode positions were localized manually using each electrode's artifact in the CT scan, projected onto a cortical surface model generated in FreeSurfer (Dale et al., 1999), and displayed on the cortical surface model for visualization (Pieters et al, 2013). Electrodes were then given anatomical labels in an automated fashion using a FreeSurfer parcellation scheme. The electrode locations were modeled using spheroids on the cortical surface model for visualization.

As mentioned above, the decoding electrode was chosen based only on the presence of premovement activity. Precise anatomical localization of this electrode was performed after the conclusion of data collection by registering a CT scan with a parcellated brain surface model generated using the patient's pre-surgical MRI in the Analysis of Functional Neuroimages software package (AFNI). An expert in human neuroanatomy (NT) then corroborated the electrode's anatomical location. Using this procedure, we determined that of the nine patients, five had decoding electrodes in the SMA.

Localizer task – Phase 1

ECoG data were analyzed offline using custom Matlab software. Spectral decomposition was done by first filtering raw signals into 120 different frequency bands. The analytic amplitude of each band was then taken as the absolute value of the Hilbert transforms of each time series. Baseline power levels for each trial were calculated using a 500 ms interval just before trial start. ERSPs were calculated using the baseline power levels and expressed as percent change from baseline [23, 26-28].

The electrical stimulus (described below) induces a large artifact in the ECoG recordings. Because our spectral analysis procedure relies on buffer data to avoid edge effects, a data reflection procedure [29] was adopted to generate ERSPs immediately preceding an electrical stimulus as follows. For each trial with a stimulation artifact, the electrode's time series was truncated 10 ms before the artifact onset. A 1500 ms long epoch of the signal preceding the stimulation artifact was then taken, reversed, and attached to the time series at the end of the epoch. Thus the new epoch was 1500 ms longer and contained the pre-artifact signal immediately followed by a mirrored copy of the pre-artifact ECoG signal. We then performed spectral decomposition using the method described above. Following spectral decomposition, the reflected epoch was discarded, leaving only the signal preceding the electrical stimulus artifact. This approach eliminates the large stimulation artifact while also preventing contamination of the spectral analysis due to edge effects.

Stimulation

We used a Grass Technologies S88X neural stimulator (Natus Medical technologies, Pleasanton, CA) with a stimulus isolation unit. The stimulator was programmed to deliver two 500 μs balanced square-wave pulses separated by 20 ms. This interval was chosen to deliver 50 Hz stimulation (gamma band), and only two pulses were selected to produce a transient disruption of the system, large enough to detect a behavioral effect but not large enough or prolonged enough to preclude movement. Balanced square-wave currents were chosen to minimize charge deposition. Current intensity was fixed at 7 mA in all cases (providing an effective, yet safe charge density for the electrodes used in the study). Patients were unable to detect stimulation events at this amplitude. Had a patient been able to detect stimulation, the current intensity would have been lowered until it was undetectable. Stimulation and nonstimulation (control) trials were randomly interleaved such that both the patient and the experimenter were blinded to the trial type.

Closed-loop system – Phase 2

Our closed-loop system was integrated several hardware components running custom software (Figure 2). For S1-S5, online closed-loop analysis was performed using a Blackrock NSP. The NSP acquired ECoG data at 30 kHz. Custom software written in C was used to rapidly measure power changes in a user-specified frequency band by first band-pass filtering a 2048 sample long segment of the re-referenced ECoG signal (68 ms) of interest. Power changes were quantified as the root mean square (RMS) value of this signal. A threshold RMS value for stimulation was then set. The RMS threshold was chosen systematically as a value that was consistently higher than the baseline noise and lower than the peak of the motion-related response. This was necessarily done in ad hoc fashion at the patient's bedside just prior to the stimulation phase of the experiment, with the goal of stimulating based on movement-related activity but before the actual motor response. When the power exceeded this threshold, a TTL pulse was sent to the stimulator, which then initiated stimulation. A very basic version of the system was found to have a delay below 10 ms. In practice, the delay depends on the frequencies being analyzed and was approximately 50-100 ms. A number of safeguards were implemented in the system to prevent errant stimulation. We configured the system to sense-and-stimulate only during the interval between trial start and the patient's first button press. We allowed the system to emit only one TTL pulse per trial to prevent repeated stimulation. Additionally, we implemented a global arm/disarm override that would prevent the system from issuing a TTL pulse even if the RMS threshold was crossed. Lastly, all stimulation was monitored closely by an experimenter present at the bedside who evaluated patient behavior as well as the clinical ECoG traces in real time.

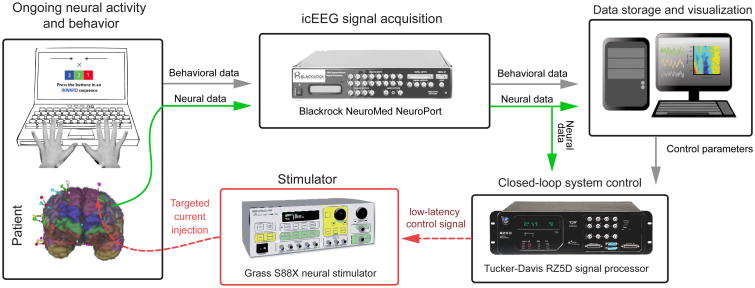

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the real time closed-loop feedback control system. This system was used in experimental Phase 3 to rapidly detect gamma power changes and trigger brain stimulation. Intracranial neural signals were acquired by a Blackrock NeuroPort system. These signals were then sent to a Tucker-Davis signal processor capable of rapid real-time frequency analysis. When gamma power exceeded a pre-defined threshold, a control signal was issued to a Grass Technologies stimulator, which then initiated an intracranial stimulation sequence (see methods section).

For patients S6-S9, a Tucker-Davis RZ5D signal processor was used to perform online analysis. In this instantiation, the Blackrock NSP passed the target electrode's re-referenced signal to the RZ5D. A virtual processing circuit was designed using the Tucker-Davis Real-Time Processor Visual Design Studio (RPvdsEx) software environment and loaded onto the RZ5D. This circuit allowed for the calculation and visualization of power changes in real time. During the 500 ms interval before each stimulation trial, the system quantified baseline power in the specified frequency band by calculating the integral power in the specified frequency band. Once the trial began, power was continuously quantified and displayed as a fraction of baseline power. Identical patient stimulation safeguards were built into this system, i.e. the system was armed/disarmed by a TTL pulse from the presentation computer, the patient was stimulated only once in a given trial, and real time monitoring of patient behavior and the clinical ECoG was performed.

The behavioral presentation computer designated each trial as a control or decoding trial with the potential for stimulation. At the beginning of a decoding trial, the presentation computer sent a TTL pulse to the online analysis system. This toggled the system from an inactive ‘disarmed’ state to an active ‘armed’ state where electrical stimulation could occur. If the patient pressed a button before an electrical stimulus was delivered, the system was immediately disarmed to prevent unnecessary current injection.

Reaction time analysis

Reaction times were measured as the time of the first button press on the hand contralateral to the stimulated hemisphere. For each experimental phase and condition (stimulated vs. control), RTs above or below the mean RT ± 2 standard deviations were designated as outliers and removed from further analysis. Similarly, trials with incomplete or incorrect button presses were excluded.

To eliminate potential practice/experience or fatigue effects, all RTs within a given experimental phase and condition were linearly detrended before further analysis. Thus, Phase 2 control and stimulation RTs were all detrended separately. All statistical analysis was performed using nonparametric procedures unless otherwise noted.

Results

Localizer Task – Phase 1

The results reported here were obtained from nine patients with at least one intracranial electrode showing pre-movement activity. Five of these patients had electrode coverage in SMA proper (S5-S9), while four patients had electrode coverage outside SMA, (S1-S4). For the patients with electrodes outside the SMA, two had electrode coverage in primary motor cortex (S2 & S3), one had electrode coverage anterior to pre-SMA (S1), and one had electrode coverage on the border of SMA and the paracentral lobule (S4). All patients participated in identical experimental procedures. The RTs for these nine patients during the localizer task are shown in Table 1. RTs did not differ between left and right hands (p > 0.05).

Table 1. Basic patient information and Phase 1 RTs.

Electrode coordinates were obtained using the Analysis of Functional Neuroimages software package (AFNI) and are listed in individual patient space.

| Subject Number | Age | Sex | Hemisphere stimulated | Decoding electrode (mm) | Cathode (mm) | Anode (mm) | Localizer task RT (ms) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | x | y | z | x | y | z | |||||

| S1 | 24 | F | R | -5.3 | 8.3 | 37.9 | 0.6 | 7.8 | 33.9 | -8.3 | 8.8 | 39.9 | 1201±45 |

| S2 | 26 | M | R | -11.6 | -36.5 | 59.9 | -9.0 | -36.0 | 57.9 | -14.8 | -36.5 | 59.9 | 890±14 |

| S3 | 21 | F | R | 2.0 | -39.1 | 60.4 | 1.2 | -39.1 | 59.4 | -5.7 | -39.6 | 60.4 | 1399±28 |

| S4 | 33 | M | L | 9.0 | -6.0 | 66.0 | 12.0 | 5.0 | 68.0 | 15.0 | -4.9 | 70.0 | 1407±53 |

| S5 | 27 | F | L | 2.9 | -35.7 | 79.9 | 0.5 | -36.3 | 78.1 | 5.8 | -35.1 | 82.1 | 1169±43 |

| S6 | 25 | M | R | -29.1 | -97.5 | 59.0 | -25.7 | -97.3 | 59.0 | -33.0 | -98.5 | 59.0 | 1630±68 |

| S7 | 45 | F | L | 12.9 | 5.3 | 44.2 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 41.2 | 9.8 | 5.3 | 42.2 | 1053±16 |

| S8 | 18 | F | R | -30.4 | -26.9 | 70.8 | 0.7 | -25.9 | 55.8 | -5.3 | -26.4 | 58.8 | 839±19 |

| S9 | 30 | F | L | 3.6 | 19.4 | 24.7 | 12.8 | 18.2 | 29.6 | 15.4 | 17.7 | 31.6 | 933±14 |

All patients had one or more electrode contacts that displayed movement-related activity. Amongst these, the contact showing the strongest pre-movement increases in gamma power was selected for online decoding in the closed-loop portion of the experiment. Once this contact was selected, the pair of the most immediately adjacent electrode contacts on the same probe was chosen for bipolar current injection (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure 1A).

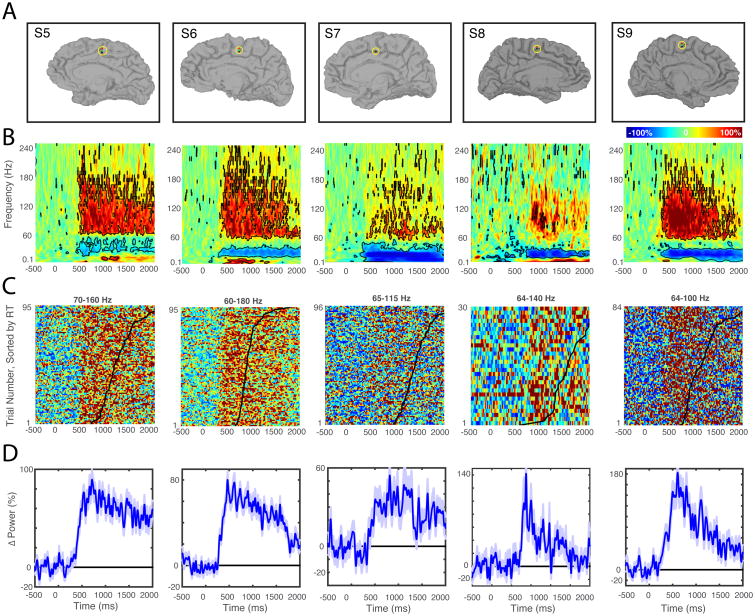

Figure 3.

Localizer task data used for electrode selection in the five SMA patients. A, Anatomical location of intra-cranial electrodes. For each patient, the electrode showing the greatest pre-movement activity (green) was chosen using data from the Phase I localizer task. Locations of anode and cathode electrodes used in subsequent stimulation phases are indicated in red and black, respectively. B, Time-Frequency spectrograms (0.1-240 Hz, linear frequency axis) locked to trial start. Spectrograms show, for each frequency, mean power changes relative to a 500 ms pre-trial baseline. Time-frequency points differing significantly from baseline activity are outlined in black (p < 0.01, t-test). These plots were used to choose gamma frequency bands of interest for online analysis in Phase 2. C, Raster plots showing single trial spectral perturbations. Each row shows the percent change in gamma power for the frequency band indicated. Trials are sorted according to RT, and a black point indicates RT for each trial. D, Average gamma power changes. For each patient, an increase in gamma power is observed within 1000 ms of trial onset. Note that ordinate axes are customized for each patient.

While the magnitude and frequency range of movement-related power changes varied across patients, there was an increase in gamma frequency power accompanied by a decrease in beta power beginning approximately 500 ms after the cue (SMA patients, Figure 3B and non-SMA patients, Supplementary Figure 1B). Next, we computed for each patient the gamma frequency band within which the greatest power increase preceding movement occurred (SMA patients, Figure 3C and non-SMA patients, Supplementary Figure 1C), for use in the closed-loop portion of the experiment (Phase 2). For most SMA patients, the maximum power increase was at least 50% greater than pre-trial baseline activity (Figure 3D; mean for the five SMA patients=102.5±22%).

Closed-loop stimulation – Phase 2

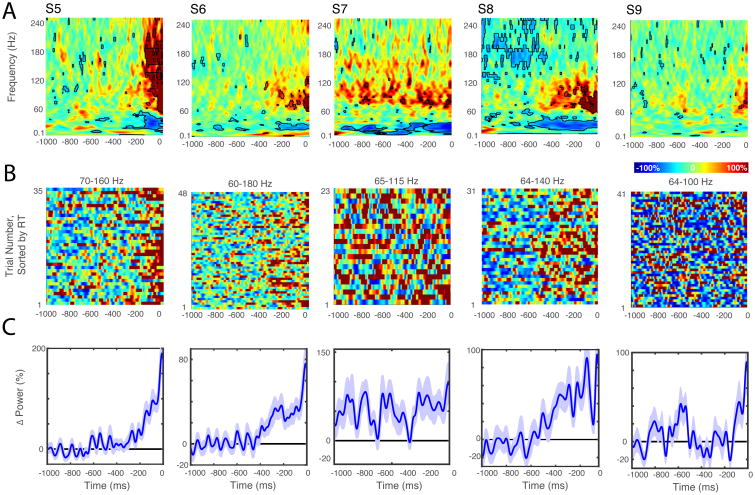

Mean ERSPs time locked to the delivery of closed loop stimulation are shown for each patient in Figure 4. Control trials (not shown) were randomly interleaved in each block. For all SMA patients there was a clear increase in gamma frequency power (∼60-180 Hz) leading up to stimulation. Gamma power increases were also evident in average traces for SMA patients (Figure 4C) and non-SMA patients (Supplementary Figure 2C).

Figure 4.

Closed-loop detection of pre-movement gamma frequency power changes. A, ERSPs preceding electrical stimulation. Spectrograms show average frequency power changes over time relative to a 500 ms pre-trial baseline. Time zero corresponds to 10 ms before the onset of current injection. Electrical stimulation introduces a large ECoG artifact that is removed by truncating and ‘reflecting’ each trial's time series prior to spectral analysis (see methods). B, Raster plots showing single trial power changes for the frequency band indicated. Time zero again corresponds to the onset of the electrical stimulus. C, Average gamma frequency power changes prior to stimulation.

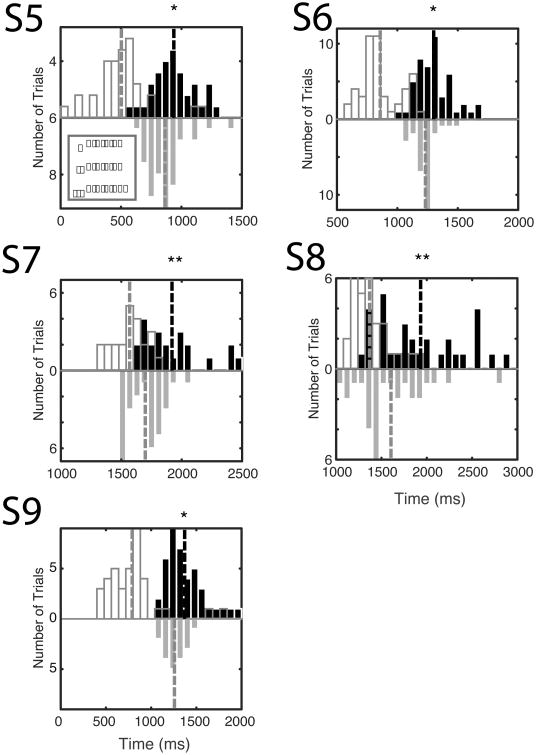

Our closed-loop system was configured to perform online power analysis and stimulate the SMA directly when power in a specified frequency band exceeded a predefined threshold. Stimulation times and RTs are shown in Figure 5 and summarized in Table 2. Overall, stimulation based on the closed-loop system significantly delayed RTs all of the SMA patients (mean=158±49 ms, all individual p<0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum). This delay in movement initiation was not observed when we stimulated outside the SMA. Specifically, three of the four patients stimulated outside SMA showed no prolongation of the RT, while patient S2 showed a slight but statistically significant speeding of RT (1164±2 vs. 1034±2 ms p<0.01 Wilcoxon rank sum).

Figure 5.

Stimulation based on the detection of gamma frequency activity resulted in significant slowing in the five SMA patients. Solid black bars show the distribution of RTs following stimulation. The distribution of stimulation times is shown with open black bars. Control RT distributions are shown as downward facing grey bars. RTs in patients S5-S9 are significantly delayed following stimulation (mean=158±49 ms, all p<0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Table 2.

Table showing Phase 2 (closed-loop SAS) results for all patients.

| Subject Number | Number of control trials | Mean control RT (ms) | Control trial Accuracy | Number of trials | Stimulation time (ms) | Mean RT for stim trials (ms) | Stim trial accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 21 | 2315±85 | 31% | 8 | 1450±18 | 2312±99 | 36% |

| S2 | 70 | 1164±20 | 86% | 16 | 355±82 | 1064±21 | 80% |

| S3 | 62 | 878±28 | 94% | 44 | 425±49 | 915±25 | 98% |

| S4 | 37 | 1039±49 | 93% | 48 | 384±49 | 961±21 | 98% |

| S5 | 37 | 864±26 | 95% | 35 | 503±37 | 937±29 | 97% |

| S6 | 29 | 1232±17 | 100% | 48 | 858±24 | 1301±21 | 98% |

| S7 | 29 | 1699±28 | 100% | 23 | 1569±26 | 1907±49 | 96% |

| S8 | 28 | 1605±73 | 98% | 31 | 1369±37 | 1932±84 | 100% |

| S9 | 19 | 1257±26 | 86% | 41 | 790±43 | 1370±33 | 95% |

As in Phase 1, there were no significant timing differences between left and right hand RTs for either condition during Phase 2 (p > 0.05). In all cases, stimulation was imperceptible to the subject, even when there were measurable changes in motor behavior.

Stimulation time and RT

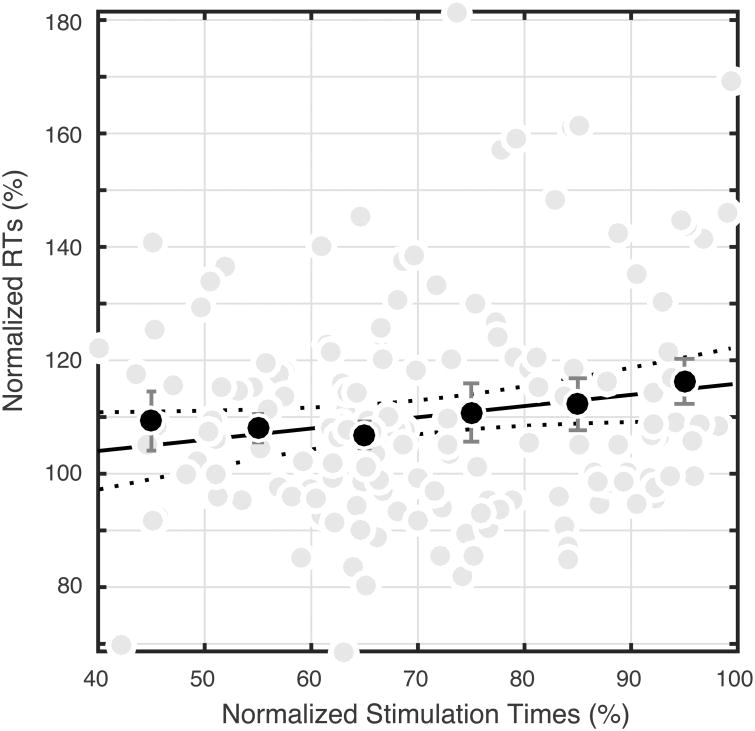

In order to better understand the relation between stimulation time and RT, for each patient, we normalized stimulation times and RTs for stimulation trials by the expected RT. Expected RT was defined as the mean RT for all control (no stimulation) trials. Stimulation and RTs were then expressed as a percentage of the expected RT so that a stimulation time (or RT) that occurred exactly when RT was expected would have a value of 100%. Stimulation times and RTs that occurred before the expected RT then have values below 100%, and those that occurred after the expected RT have values exceeding 100% (see Figure 6). To alleviate the influence of sparse sampling, time bins (each decile of normalized stimulation times, e.g. 10%-20%) containing fewer that five trials are not included (n=21). Mean RTs within each stimulation decile are significantly slower than the distribution of control RTs (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon rank sum), with the 90-100% decile having the greatest delay. This analysis indicates that, on average, stimulation just prior to the expected RT leads to delays of ∼15%.

Figure 6.

Group relationships between stimulation times, RTs, and expected RTs. For each SMA patient, stimulation times (abscissa) and RTs following stimulation (ordinate) were normalized for mean RT for control trials in a given experimental phase. Grey points show Phase 2 data. Black points depict the average normalized RT within each decile of normalized stimulation times (e.g. 10%-20%). There is a significant positive relationship between the time of stimulation and the normalized RT as shown by the black linear regression line (p<0.05, R20.02).

Discussion

We designed and implemented a sense-and-stimulate system that detects pre-movement high gamma frequency power changes in real time and then stimulates the cortex directly. We tested the system in nine patients. In the five patients where this closed loop stimulation targeted the SMA, it significantly delayed reaction times (relative to no stimulation trials). In none of the four patients with electrodes outside the SMA did closed loop stimulation result in significant RT changes (even though a premovement gamma increase was detected by the algorithm). The fourth non-SMA patient showed a slight speeding of RTs. Subsequent analysis of the ECoG data validated the real time detection method by showing that in all patients there was a gamma increase before stimulation was delivered. These results clearly indicate that impending movement can be detected and used to trigger direct stimulation of SMA to influence ongoing motor behavior in a predictable manner imperceptible to the subject. The SMA, (and other premotor cortices) manifest movement related activity well in advance of actual movement, such that stimulation may reasonably be expected to perturb ongoing processes and result in a delay in movement execution. Stimulation of further downstream regions such as M1 likely occur too late relative to the “committed” nature of the process at these locations, to result in any change in execution. These results also imply that SMA is a suitable candidate for designing and evaluating the performance of SAS brain-computer interfaces.

Prior attempts at the development of human neural SAS systems have involved technologies such as EEG or fMRI, which are subject to spatial or temporal signal limitations. On the stimulation end, systems using transcranial electrical or magnetic stimulation are limited in their ability to perform circuit-specific neuromodulation. In contrast, intracranial SAS allows for both circuit-specific activity detection and neuromodulation [3]. We have shown that this is possible in the human motor system using a threshold-based decoding and closed-loop current injection procedure. However, for SAS to be effective in the treatment of affective disorders or for the modulation of say, memory systems, more sophisticated decoding algorithms and pattern recognition techniques will likely become necessary [30]. Similarly, more sophisticated stimulation procedures, such as time-varying phase and amplitude current injection will be necessary for more nuanced neuromodulation [4]. It is worth noting that the stimulation parameters used here were chosen as a reasonable starting point, and the efficacy of other protocols involving different numbers, strengths, and frequencies of pulses remains unexplored. The SAS system we describe here can serve as a test bed for exploring more sophisticated intracranial decoding and stimulation protocols.

We chose to focus on activity in the SMA because it is commonly implanted with stereotactic depth electrodes, and especially because the SMA shows characteristic electrophysiological activity hundreds of milliseconds prior to the onset of voluntary movement. Indeed, the SMA is implicated as a generator of the readiness potential (‘Bereitschaftspotential’), seen in EEG recordings preceding voluntary movement by up to 2 s [31, 32]. We chose a task involving complex motor sequences and bilateral limb coordination because these movements have been shown to evoke stronger SMA activity than simple unilateral or repetitive movements [33, 34]. The interval between the onset of this activity and observable motor behavior provided a suitably long time window during which closed-loop detection and stimulation could occur.

Stimulation of the kind we delivered could potentially augment the endogenous activity of the SMA, or it could disrupt movement planning and execution. The fact that stimulation delayed RT, even when delivered fairly early in the trial relative to RT in some cases, suggests that it disrupts processes necessary for movement generation. These results build on other studies that seek to determine optimal parameters for direct electrical stimulation of the human brain [35-37].

A natural question is whether stimulation at any period in the trial might have had a similar delaying effect. Stimulation near the expected RT resulted in longer delays (Figure 6). In other studies, repetitive TMS of SMA also produces behavioral delays similar to those seen in the present study [38]. TMS of M1 close to the time of expected movement also causes response delays [39]. While primary motor cortex is considered to be the major output zone for motor cortex, the SMA proper also has direct spinal projections [40, 41]. Indeed, some SMA neurons project to spinal motor neurons monosynaptically [20, 42]. Thus, stimulating SMA in the manner described here may perturb processing at various levels of the motor network.

While the SMA does contribute to bilateral motor coordination, it appears to be more intimately involved in contralateral motor control [38, 43, 44]. In this study, stimulation occurred only in one hemisphere, and contralateral RTs were taken as the primary dependent measure. However, RTs from the hand ipsilateral to stimulation also showed similar RT delays following stimulation. Moreover, behavioral task accuracy was not affected by stimulation (Table 2). Taken together, these findings support ideas of bilateral SMA organization with redundancies, in which stimulation can slow movement, but one hemisphere can compensate for potential errors in the contralateral motor program.

There are a few caveats to this work. First, we assume that the effects of stimulation are immediate and brief, and do not carry over from trial to trial. This is reasonable given that we only injected two brief pulses of current, based on current understanding of cortical physiology [45, 46]. Second, as reported elsewhere [47], broadband gamma increases are often accompanied by beta band power decreases during self-paced movements. While we only examined broadband gamma changes here, the utility of beta band changes for sense-and-stimulate protocols should be explored in future research. Third, due to pragmatic considerations of time, and the fact that pre-movement related activity was only present in specific electrodes (whose placement was guided by clinical considerations) we only examined the effects of stimulation at one site in a given patient. Future studies should compare the specificity of this SAS approach to the SMA itself. Fourth, a particular value of the SAS approach would be to try to discover a ‘sweet spot’ for brain stimulation – i.e. maximally impact motor behavior by delivering stimulation specifically timed to on ongoing activity. In the SAS part of this study there is no evident ‘sweet spot’ (Figure 6), except that stimulation closer to the button press led to a greater delay in response. Chronometric stimulation necessarily depends upon cued behavior. It cannot be used in the context of volitional behavior. A comprehensive evaluation of the SAS method will require a comparison with chronometric stimulation that occurs in roughly the same time-frame but is not triggered by sensing but instead along a regular distribution of times prior to action. Yet developing SAS targeted at movement planning/initiation is a more promising approach for neuroprosthetics, for example to eventually develop modes that suppress or facilitate voluntary uncued action. Response-based optimization of SAS will be a target of future work.

Conclusions

We show that a cortical SAS system using electrodes in the SMA for real-time triggering using gamma power increases related to movement to modulate motor behavior on the same trial. This work should help establish the SAS method in humans and facilitate the development of the next generation of neuromodulatory devices for affecting movement. Our data are also a useful starting point for providing information about the cortical stimulation parameters that alter, and in this case, slow movement.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Localizer task data used for electrode selection in the four non-SMA patients. A, Anatomical location of intra-cranial electrodes. For each patient, the electrode showing the greatest pre-movement activity (green) was chosen using data from the Phase I localizer task. Locations of anode and cathode electrodes used in subsequent stimulation phases are indicated (where visible) in red and black, respectively. B, Time-Frequency spectrograms (0.1-240 Hz, linear frequency axis) locked to trial start. Time-frequency points differing significantly from baseline activity are outlined in black (p < 0.01, t-test). C, Raster plots showing single trial spectral perturbations. Each row shows the percent change in gamma power for the frequency band indicated. Trials are sorted according to RT, and a black point indicates RT for each trial. D, Average gamma power changes.

Supplementary Figure 2: Closed-loop detection of pre-movement gamma frequency power changes for the non-SMA patients. A, ERSPs preceding electrical stimulation. Spectrograms show average frequency power changes over time relative to a 500 ms pre-trial baseline. B, Raster plots showing single trial power changes for the frequency band indicated. C, Average gamma frequency power changes prior to stimulation.

Highlights.

- In humans, the supplementary motor area manifests characteristic neural activity just prior to voluntary movement.

- We developed a closed-loop deep brain stimulation system capable of detecting this activity and stimulating the SMA before movement occurs.

- Stimulation based on closed-loop detection of SMA activity resulted in significant slowing of motor behavior.

- Stimulation using an identical protocol outside the SMA did not result in significant slowing of motor behavior.

- This is the first report of a human closed loop system designed to alter movement using direct cortical recordings and direct stimulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients for their time and co-operation with the study, the Memorial Hermann Hospital Epilepsy Monitoring Unit staff for their support, and Matthew J. Rollo for technical help in recordings. We also thank Kamin Kim for editing an earlier version of the manuscript. Funding for this project was provided by NIH grants DA026452 and DC014589.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rowland NC, De Hemptinne C, Swann NC, Qasim S, Miocinovic S, Ostrem JL, et al. Task-related activity in sensorimotor cortex in Parkinson's disease and essential tremor:changes in beta and gamma bands. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:512. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Hemptinne C, Swann NC, Ostrem JL, Ryapolova-Webb ES, San Luciano M, Galifianakis NB, et al. Therapeutic deep brain stimulation reduces cortical phase-amplitude coupling in Parkinson's disease. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(5):779–86. doi: 10.1038/nn.3997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrington TM, Cheng JJ, Eskandar EN. Mechanisms of deep brain stimulation. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115(1):19–38. doi: 10.1152/jn.00281.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moxon KA, Foffani G. Brain-machine interfaces beyond neuroprosthetics. Neuron. 2015;86(1):55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergmann TO, Molle M, Schmidt MA, Lindner C, Marshall L, Born J, et al. EEG-guided transcranial magnetic stimulation reveals rapid shifts in motor cortical excitability during the human sleep slow oscillation. J Neurosci. 2012;32(1):243–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4792-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zrenner C, Belardinelli P, Muller-Dahlhaus F, Ziemann U. Closed-Loop Neuroscience and Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation: A Tale of Two Loops. Front Cell Neurosci. 2016;10:92. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Ridder D, Vanneste S. EEG Driven tDCS Versus Bifrontal tDCS for Tinnitus. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:84. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2012.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancelli A, Cottone C, Tecchio F, Truong DQ, Dmochowski J, Bikson M. A simple method for EEG guided transcranial electrical stimulation without models. J Neural Eng. 2016;13(3):036022. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/13/3/036022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Little S, Pogosyan A, Neal S, Zavala B, Zrinzo L, Hariz M, et al. Adaptive deep brain stimulation in advanced Parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(3):449–57. doi: 10.1002/ana.23951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hickey P, Stacy M. Deep Brain Stimulation: A Paradigm Shifting Approach to Treat Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:173. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergey GK, Morrell MJ, Mizrahi EM, Goldman A, King-Stephens D, Nair D, et al. Longterm treatment with responsive brain stimulation in adults with refractory partial seizures. Neurology. 2015;84(8):810–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas GP, Jobst BC. Critical review of the responsive neurostimulator system for epilepsy. Med Devices (Auckl) 2015;8:405–11. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S62853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Passingham RE. Functional specialization of the supplementary motor area in monkeys and humans. Adv Neurol. 1996;70:105–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amador N, Fried I. Single-neuron activity in the human supplementary motor area underlying preparation for action. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(2):250–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried I, Mukamel R, Kreiman G. Internally generated preactivation of single neurons in human medial frontal cortex predicts volition. Neuron. 2011;69(3):548–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohara S, Ikeda A, Kunieda T, Yazawa S, Baba K, Nagamine T, et al. Movement-related change of electrocorticographic activity in human supplementary motor area proper. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 6):1203–15. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunieda T, Ikeda A, Ohara S, Yazawa S, Nagamine T, Taki W, et al. Different activation of presupplementary motor area, supplementary motor area proper, and primary sensorimotor area, depending on the movement repetition rate in humans. Exp Brain Res. 2000;135(2):163–72. doi: 10.1007/s002210000519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narayana S, Laird AR, Tandon N, Franklin C, Lancaster JL, Fox PT. Electrophysiological and functional connectivity of the human supplementary motor area. Neuroimage. 2012;62(1):250–65. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wessel K, Zeffiro T, Toro C, Hallett M. Self-paced versus metronome-paced finger movements. A positron emission tomography study. J Neuroimaging. 1997;7(3):145–51. doi: 10.1111/jon199773145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Picard N, Strick PL. Activation of the supplementary motor area (SMA) during performance of visually guided movements. Cereb Cortex. 2003;13(9):977–86. doi: 10.1093/cercor/13.9.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peirce JW. PsychoPy--Psychophysics software in Python. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162(1-2):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peirce JW. Generating Stimuli for Neuroscience Using PsychoPy. Front Neuroinform. 2008;2:10. doi: 10.3389/neuro.11.010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Conner CR, Ellmore TM, Pieters TA, DiSano MA, Tandon N. Variability of the relationship between electrophysiology and BOLD-fMRI across cortical regions in humans. J Neurosci. 2011;31(36):12855–65. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1457-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makeig S. Auditory event-related dynamics of the EEG spectrum and effects of exposure to tones. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;86(4):283–93. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(93)90110-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wessel JR, Conner CR, Aron AR, Tandon N. Chronometric electrical stimulation of right inferior frontal cortex increases motor braking. J Neurosci. 2013;33(50):19611–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3468-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conner CR, Chen G, Pieters TA, Tandon N. Category Specific Spatial Dissociations of Parallel Processes Underlying Visual Naming. Cereb Cortex. 2013;24(10):2741–2750. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadipasaoglu CM, Conner CR, Whaley ML, Baboyan VG, Tandon N. Category-Selectivity in Human Visual Cortex Follows Cortical Topology: A Grouped icEEG Study. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whaley ML, Kadipasaoglu CM, Cox SJ, Tandon N. Modulation of Orthographic Decoding by Frontal Cortex. J Neurosci. 2016;36(4):1173–84. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2985-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen MX. Analyzing neural time series data theory and practice. The MIT Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim K, Ekstrom AD, Tandon N. A network approach for modulating memory processes via direct and indirect brain stimulation: Toward a causal approach for the neural basis of memory. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2016;134 Pt A:162–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shibasaki H, Hallett M. What is the Bereitschaftspotential? Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117(11):2341–56. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colebatch JG. Bereitschaftspotential and movement-related potentials: origin, significance, and application in disorders of human movement. Mov Disord. 2007;22(5):601–10. doi: 10.1002/mds.21323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deiber MP, Honda M, Ibanez V, Sadato N, Hallett M. Mesial motor areas in self-initiated versus externally triggered movements examined with fMRI: effect of movement type and rate. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81(6):3065–77. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.6.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roland PE, Larsen B, Lassen NA, Skinhoj E. Supplementary motor area and other cortical areas in organization of voluntary movements in man. J Neurophysiol. 1980;43(1):118–36. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karnath HO, Borchers S, Himmelbach M. Comment on “Movement intention after parietal cortex stimulation in humans”. Science. 2010;327(5970):1200. doi: 10.1126/science.1183758. author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borchers S, Himmelbach M, Logothetis N, Karnath HO. Direct electrical stimulation of human cortex - the gold standard for mapping brain functions? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(1):63–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn3140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Desmurget M, Song Z, Mottolese C, Sirigu A. Re-establishing the merits of electrical brain stimulation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(9):442–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serrien DJ, Strens LH, Oliviero A, Brown P. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation of the supplementary motor area (SMA) degrades bimanual movement control in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2002;328(2):89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00499-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziemann U, Tergau F, Netz J, Homberg V. Delay in simple reaction time after focal transcranial magnetic stimulation of the human brain occurs at the final motor output stage. Brain Res. 1997;744(1):32–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanji J. The supplementary motor area in the cerebral cortex. Neurosci Res. 1994;19(3):251–68. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macpherson J, Wiesendanger M, Marangoz C, Miles TS. Corticospinal neurones of the supplementary motor area of monkeys. A single unit study. Exp Brain Res. 1982;48(1):81–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00239574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maier MA, Armand J, Kirkwood PA, Yang HW, Davis JN, Lemon RN. Differences in the corticospinal projection from primary motor cortex and supplementary motor area to macaque upper limb motoneurons: an anatomical and electrophysiological study. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12(3):281–96. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donchin O, Gribova A, Steinberg O, Bergman H, Vaadia E. Primary motor cortex is involved in bimanual coordination. Nature. 1998;395(6699):274–8. doi: 10.1038/26220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brinkman C. Lesions in supplementary motor area interfere with a monkey's performance of a bimanual coordination task. Neurosci Lett. 1981;27(3):267–70. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90441-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ranck JB., Jr Which elements are excited in electrical stimulation of mammalian central nervous system: a review. Brain Res. 1975;98(3):417–40. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(75)90364-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanakawa T, Ikeda A, Sadato N, Okada T, Fukuyama H, Nagamine T, et al. Functional mapping of human medial frontal motor areas. The combined use of functional magnetic resonance imaging and cortical stimulation. Exp Brain Res. 2001;138(4):403–9. doi: 10.1007/s002210100727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfurtscheller G, Graimann B, Huggins JE, Levine SP, Schuh LA. Spatiotemporal patterns of beta desynchronization and gamma synchronization in corticographic data during self-paced movement. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114(7):1226–36. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Localizer task data used for electrode selection in the four non-SMA patients. A, Anatomical location of intra-cranial electrodes. For each patient, the electrode showing the greatest pre-movement activity (green) was chosen using data from the Phase I localizer task. Locations of anode and cathode electrodes used in subsequent stimulation phases are indicated (where visible) in red and black, respectively. B, Time-Frequency spectrograms (0.1-240 Hz, linear frequency axis) locked to trial start. Time-frequency points differing significantly from baseline activity are outlined in black (p < 0.01, t-test). C, Raster plots showing single trial spectral perturbations. Each row shows the percent change in gamma power for the frequency band indicated. Trials are sorted according to RT, and a black point indicates RT for each trial. D, Average gamma power changes.

Supplementary Figure 2: Closed-loop detection of pre-movement gamma frequency power changes for the non-SMA patients. A, ERSPs preceding electrical stimulation. Spectrograms show average frequency power changes over time relative to a 500 ms pre-trial baseline. B, Raster plots showing single trial power changes for the frequency band indicated. C, Average gamma frequency power changes prior to stimulation.