Abstract

The Sox gene family consists of several genes related by encoding a 79 amino acid DNA-binding domain known as the HMG box. This box shares strong sequence similarity to that of the testis determining protein SRY. SOX proteins are transcription factors having critical roles in the regulation of diverse developmental processes in the animal kingdom. We have characterised the human SOX7 gene and compared it to its mouse orthologue. Chromosomal mapping analyses localised mouse Sox7 on band D of mouse chromosome 14, and assigned human SOX7 in a region of shared synteny on human chromosome 8 (8p22). A detailed expression analysis was performed in both species. Sox7 mRNA was detected during embryonic development in many tissues, most abundantly in brain, heart, lung, kidney, prostate, colon and spleen, suggesting a role in their respective differentiation and development. In addition, mouse Sox7 expression was shown to parallel mouse Sox18 mRNA localisation in diverse situations. Our studies also demonstrate the presence of a functional transactivation domain in SOX7 protein C-terminus, as well as the ability of SOX7 protein to significantly reduce Wnt/β-catenin-stimulated transcription. In view of these and other findings, we suggest different modes of action for SOX7 inside the cell including repression of Wnt signalling.

INTRODUCTION

In mammals, a single gene on the Y chromosome determines the sex of the organism by inducing testicular development from the gonadal primordium (reviewed in 1). This gene termed Sry (sex determining region of the Y chromosome) encodes a high-mobility-group (HMG) DNA-binding domain containing protein that exhibits sequence-specific binding activity (2). The name SOX (SRY box containing) has been given for HMG containing proteins sharing >60% homology to SRY in the HMG box region. At least 30 members of the SOX family have been so far identified and are expressed in many different cell types and tissues at multiple stages during development throughout the animal kingdom (3,4). They are now widely recognized as key players in the regulation of embryonic development and in the determination of different cell fates.

The precise function(s) of many SOX proteins is still unknown, although they have been proposed to be transcription factors that bend DNA upon binding to the minor groove of the DNA helix at the consensus sequence 5′-(A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G-3′ (5,6). Most assigned roles for SOX proteins in development are the result of gene targeting experiments in mouse or positional cloning for described human syndromes. Mutations of human SOX9 leads to campomelic dysplasia, a bone dysmorphogenesis often associated with male to female sex reversal (7,8). Sox10 mutation leads to a combination of neural crest defects as observed in the Hirchsprung Dom mouse model (9) or to combined Waardenburg–Hirchsprung syndrome in humans (10). Sox1 deletion causes microphtalia and cataracts in homozygous mice (11), Sox4–/– mutated mice die prematurely because of defects in endocardial ridges and B-lymphocyte development (12), and mice homozygous for a null mutation of Sox6 die just after birth from cardiac conduction defects (13).

Sox genes were further divided into nine subgroups (A–I) based on the degree of homology inside the HMG domain and the presence of conserved motifs outside the HMG box (14). Subgroup F is thus formed from three closely related SOX proteins, namely SOX7, SOX17 and SOX18. In Xenopus, SOX17 protein functions as an early endoderm inducer (15) and is expressed during spermatogenesis in mouse (16). Point mutations in Sox18 underlie cardiovascular and hair follicle defects in ragged mice (17), whereas Sox18–/– mice are viable and display a mild coat defect (18). Although few examples of possible functional redundancy between SOX proteins were previously described (19), many cell types or tissues express more than one Sox gene at any given time.

Sox7 was first identified in Xenopus and in mouse (20,21). To gain further insights into the modes of action and function of SOX7, several findings are described in the present study. First, the human SOX7 open reading frame (ORF) sequence was cloned. Sox7 expression analyses and chromosomal localisation were carried out in both mouse and human. Moreover, expression studies revealed some overlap with mouse Sox18 expression. Transactivation studies have revealed the capacity of SOX7 protein to act as a transcriptional activator. Importantly, we also demonstrate, by using transfection experiments in the human kidney 293 cell line, that SOX7 inhibits, in a dose-dependent manner, the ability of TCF/LEF-β-catenin to transactivate a TCF/LEF-dependent reporter construct, suggesting a role for SOX7 in the modulation of the Wnt signalling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human SOX7 ORF sequence and analysis

PCR was performed on 5 ng of Human Fetal Thymus Marathon-Ready cDNA (Clontech) in a 50 µl reaction using Pfu polymerase according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega). P1 and P2 primers were designed from the mouse sequence (GenBank accession no. AB023419) and used to amplify the coding region of human SOX7 (EcoRI and XhoI enzymatic sites are underlined): P1, 5′-ATGAATTCATGGCCTCGCTGCTGGGCG-3′; and P2, 5′-ATCTCGAGCTATGACACACTGTTGTAATACGTGGC-3′. The resulting PCR fragments were cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen), and different subclones were finally sequenced. Homology searches of the dbEST section of GenBank using the human SOX7 coding sequence as the query uncovered five human expressed sequence tags (ESTs) with sequence identities to SOX7. These ESTs derived from cDNA clones of pancreas and ovary (GenBank accession nos BE531107, BF732608, AA909543, BE615038 and BE614975). Only the first three were accessible at the ATCC and sequenced to both confirm and complete the SOX7 coding sequence. The nucleotide sequence of the SOX7 ORF is deposited in EMBL databases under the accession number AJ409320.

Genomic clones and hybridisation probes

To isolate both murine and human SOX7 genomic clones, DNA pools from the RPCI-21 mouse PAC library and the RPCI-11 human male BAC library (provided by the German Human Genome Project Resource Center, Berlin, Germany) were screened using the mouse Sox7 probe (A) and the human SOX7 probe (B), respectively. Probe A (859 bp fragment) was amplified from mouse genomic DNA with the forward primer 5′-GCACAGCTGCTACCGCGAAGG-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-AATCCTACTGCAAACAGCTCCCAAGG-3′ based on the published mouse Sox7 cDNA sequence.

Human probe B (550 bp fragment) was amplified by PCR, using a SOX7 containing EST (accession no. AA90954) as template and the primer pair 5′-GCGGCTGTGCAAGCGCGTGG-3′ and 5′-CGGGAGTAATAGGCAGGAGATGGGGG-3′. Both probes were designed to exclude the HMG domain and were checked by sequencing.

For obtaining the mouse Sox18 probe, a PCR amplification was performed using mouse genomic DNA as template and primers derived from mouse Sox18 released sequence (accession no. L35032): forward, 5′-CGCAGGTCTCTACTATGGCACCC-3′; and reverse, 5′-CCGGCAAAGTAAACAGAACAGCC-3′.

Fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) mapping

Mouse Sox7 mapping. Metaphase spreads were prepared from a WMP strain female mouse, in which all the autosomes except chromosome 19 are in the form of metacentric Robertsonian translocations (22). Concanavalin A-stimulated lymphocytes were cultured at 37°C for 72 h with 5-bromodeoxyuridine added for the final 6 h of culture (60 µg/ml of medium) to ensure a chromosomal R-banding of good quality. The Sox7 PAC clone was biotinylated by random priming with biotin 14-dUTP following the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). Labelled probe was annealed with a 150-fold excess of murine Cot-1 DNA (Gibco BRL) (45 min at 37°C) in order to absorb labelled repetitive sequences. Hybridisation to chromosome spreads was performed with a standard protocol. The biotin-labelled DNA was added to the hybridisation solution at a final concentration of 10 µg/ml and 10 µl were used per slide. The hybridised probe was detected by means of fluorescence isothiocyanate-conjugated avidin (Vector laboratories). Chromosomes were counterstained and R-banded with propidium iodide diluted in antifade solution pH 11, as described previously (23).

Human SOX7 mapping. Metaphase spreads were prepared from phytohemagglutinin-stimulated human lymphocytes, cultured at 37°C for 72 h. 5-Bromodeoxyuridine was added for the final 7 h of culture (60 µg/ml of medium). The SOX7 BAC was labelled by random priming with biotin 14-dCTP (Bioprime DNA labelling system, Life Technologies). Before hybridisation, the labelled probes were annealed with a 150-fold excess of Cot-1 human DNA (Life Technologies) (45 min at 37°C) in order to compete the non-specific repetitive sequences. Hybridisation to chromosome spreads was performed with standard protocol (24). For each slide, 100 ng of each labelled DNA was used. The hybridised probe was detected by means of fluorescence isothiocyanate-conjugated avidin (Vector laboratories). Chromosomes were counterstained and R-banded with propidium iodide diluted in antifade solution pH 11, as described previously (25).

Northern blot hybridisation

Mouse total RNAs from different embryonic and adult tissues were prepared using the Tri reagent extraction protocol (Molecular Research Center Inc.). Northern blots were prepared using Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), with 20 µg of total RNA sample loaded per lane. The membranes were hybridised with the 32P related labelled probe (mouse Sox7 or Sox18), washed at high stringency (0.1× SSC, 0.1% SDS, 65°C) and subjected to phosphorimager analysis. Human multiple adult tissue northern membranes (Clontech) were hybridised with the human probe and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In situ hybridisation

Antisense and sense digoxigenin-labelled (or biotin-labelled) transcripts were made by in vitro transcription of linearised pBluescript (KS) containing either probe A, probe B or mouse Sox18 probe according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche). Preparation of embryos including subsequent steps for in situ hybridisation in both mouse and human, were performed as described previously (26), with minor modifications. Mouse embryos of different developmental stages were collected from Swiss strain mice (Janvier, France). Human embryos were obtained from surgical abortions in accordance with the guidelines of the CNRS Ethics Committee and the French National Ethics Committee, and were staged according to the recognised Carnegie stages (C.S.) (27). Whole-mount hybridisation was performed on 8, 9.5 and 11.5 days post-coïtum (d.p.c.) mouse embryos, and section in situ hybridisation was carried out on cryostat sections of 17.5 d.p.c. mice and C.S.19 human embryos. Both antisense probes and negative control sense probes were used on a minimum of three embryos from each stage analysed in three separate experiments.

Constructs

SOXLUC/SACLUC, TOPFLASH/FOPFLASH luciferase reporter plasmids, β-cateninS33 plasmid and the modified vector pGlomyc construct were a generous gift from Prof. H. Clevers (Utrecht, Netherlands). The five mouse Sox7 complete and deleted constructs, shown in Figure 5, were inserted into the Myc-tagged modified pcDNA vector pGlomyc. The full-length mouse Sox7 plasmid (nucleotides 1–1143) was amplified by PCR using primers P1 and P2 and an embryonic murine intestinal cDNA as template, and the resulting EcoRI–XhoI FLSox7 fragment was cloned into pGlomyc. Three clones truncated at the C-terminal end (nucleotides 1–482, 1–661, 1–762) were separately generated from the FLSox7 clone after digestion with EcoRI–ScaI, EcoRI–BstEII and EcoRI–MscI, respectively. Cloning a PCR amplification product containing only the Sox7 HMG box encoding sequence (nucleotides 105–387) generated the fifth construct. All constructs were checked by sequencing.

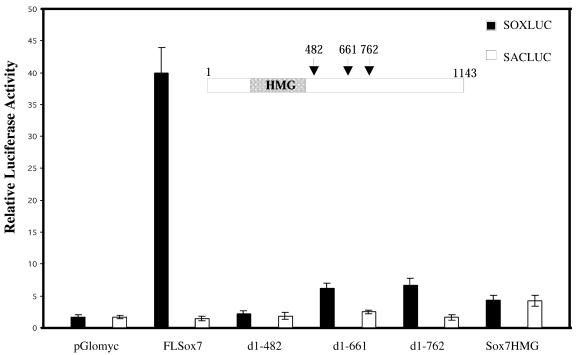

Figure 5.

SOX7 acts as a transcriptional activator through its C-terminus. COS7 cells were transiently co-transfected with either FLSox7 (0.5 µg) or one of the Sox7 deletion mutants (0.5 µg) in presence of SOXLUC [a reporter-LUC plasmid containing seven copies of the AACAAAG motif inserted upstream of a minimal herpes simplex thymidine kinase (TK) promoter]. As a control, SACLUC construct was used (a TK–LUC vector in which the seven copies had been replaced by seven CCGCGGT copies). Transfection experiments were repeated three times, and a representative experiment is shown.

Luciferase assays

Cells (5 × 104) from either COS7 or 293 cell lines were transfected using Fugene 6 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). Transfection experiments were done in triplicate and cells were harvested after 48 h. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) and normalised using the Renilla luciferase activity.

Immunofluorescence

At 48 h after transfection, transfected COS7 cells were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 5 min, extracted in acetone at –20°C for 1 min, and then incubated for 30 min with anti-Myc 9E10 (diluted 1/100 in PBS–BSA) at 37°C. After several washes with PBS, staining revelation was carried out by incubation for 30 min with fluorescein conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Cappel) at a dilution of 1/40. DNA was stained by Hoechst 33286. Cells were washed, mounted in Fluorsave reagent (Calbiochem) and immediately photographed.

RESULTS

Sequence of human SOX7 coding region

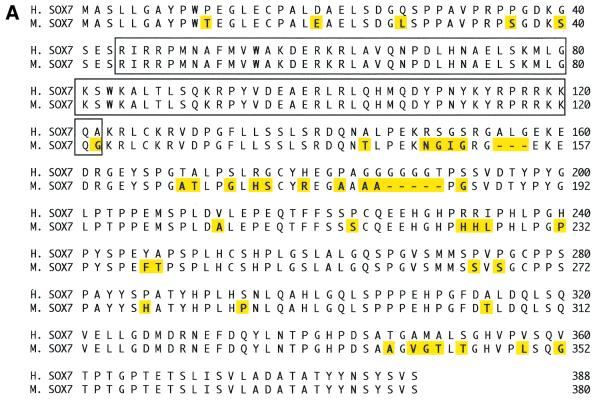

To identify human SOX7 ORF sequence, PCR on Human Fetal Thymus Marathon-Ready cDNA was performed as described in Materials and Methods. We then searched for human ESTs in the GenBank database using the human SOX7 ORF as the query sequence. Three of the obtained ESTs (Genbank accession nos BE531107, BF732608, AA909543) have been sequenced to obtain a full-length ORF sequence. This sequence encodes a 388 amino acid protein (Fig. 1A), with an HMG box DNA-binding domain spanning residues 44–122, including two putative nuclear localisation signals at both ends of the domain. Exon–intron boundaries inside the ORF were confirmed by a draft genomic sequence (GA × 4HGKP3TFSM) deposited in the Celera databank (28). The human SOX7 gene contains at least two exons separated by one intron located in the HMG box at the same position as found in other Sox gene sequences within the same subgroup F (SOX17 and SOX18) and within subgroup D (Sox5, Sox6 and Sox13) (14,28). Alignment between human (GenBank accession no. AJ409320) and mouse SOX7 proteins (21) revealed 87.4% identity (Fig. 1A) with 100% identity in the HMG box.

Figure 1.

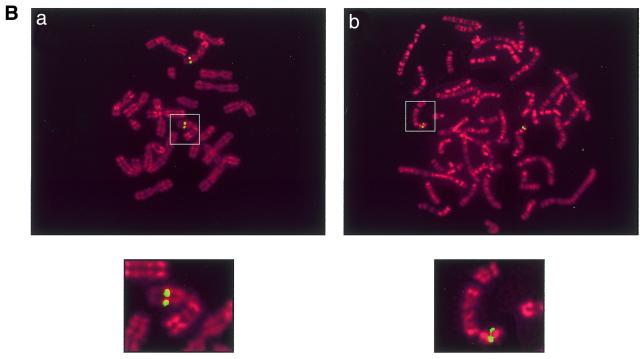

(A) Comparison between human and mouse SOX7 protein sequences. The sequence comparison was made using the MEGALIGN program of DNASTAR package. The boxed region indicates the HMG box. Amino acids for both proteins are numbered on the right. Non-identical amino acids are indicated by shadowed boxes. H, human; M, mouse. (B) Chromosomal localisation of SOX7 genes. Probes appear in green and chromosomes are counterstained in red with propidium iodide. (a) Localisation of the Sox7 PAC probe on WMP murine metaphase chromosomes. The green fluorescent signal is located in chromosome 14 band D [Robertsonian translocation Rb (5,14)]. (b) FISH mapping of the SOX7 BAC probe to human metaphase chromosomes. The green fluorescent signal is located at the 8p22 band. Magnified views of relevant chromosomes are shown below each related figure as insets.

Chromosomal localisation of mouse and human Sox7 genes

A mouse PAC library and a human BAC library were screened. Two clones (RPCI-21 614A20 and RPCI-11 49I23) were isolated and used to determine the chromosomal localisation of mouse and human SOX7 genes, respectively. Using PAC RPCI-21 614A20 as a probe, FISH with 30 metaphase chromosome spreads assigned mouse Sox7 to chromosome 14 band D (Fig. 1B, a). For human, a total of 30 metaphase spreads were probed using RPCI-11 49I23, and 90% of the cells showed specific fluorescent spots on chromosome 8 at position p22 (Fig. 1B, b), a region of shared synteny with mouse chromosome 14 (29). In addition, we detected by PCR amplification the presence of the genetic marker STSG29953 in the 3′UTR region of human SOX7 (data not shown), and this agrees with the human FISH analysis. In fact, STSG29953 has been previously mapped between the two microsatellite markers D8S518 and D8S277 located at 6.5 and 8.4 cM distal to the human 8p telomere, respectively.

Expression of mouse Sox7 and human SOX7 genes

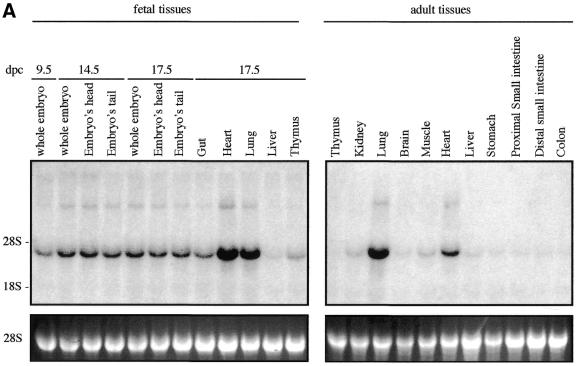

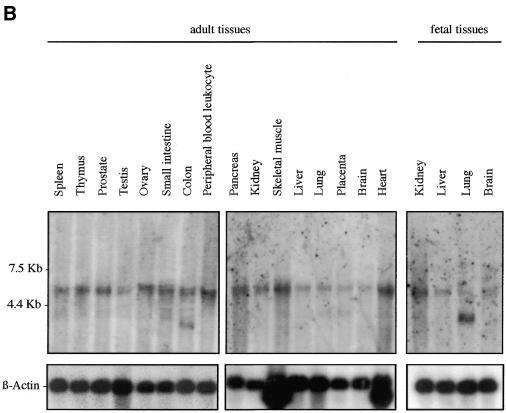

We examined Sox7 expression in mouse and human by northern blotting and in situ hybridisation. Previous analyses in the adult mouse have revealed that Sox7 expression is restricted mainly to oocytes and heart (21). However, the spatial and temporal expression pattern of Sox7 during mouse development has not been so far reported. To gain information on the expression profile of the mouse Sox7 mRNA, a large panel of total RNAs from fetal and adult mouse tissues were hybridised with the mouse probe A (see Materials and Methods). A major band of ∼4 kb is detected in all tissues examined (Fig. 2A). Significant embryonic Sox7 expression is observed in the lanes from 9.5 until 17.5 d.p.c., with stronger expression in heart and lung. In the adult stage, heart and lung display again the strongest signals while other tissues are weakly positive. For human expression analysis, fetal and adult human tissue northern blots were hybridised with the human probe B. A major transcript of ∼5 kb is seen in all lanes (Fig. 2B), but at markedly variable levels. An additional band at ∼2.5 kb is detected in the adult colon and, along with a slightly larger transcript, in the fetal lung. These bands could reflect putative splice variants or unspliced messengers.

Figure 2.

Expression profile of mouse and human Sox7 transcripts. (A) Northern blots of total RNAs from various fetal and adult mouse tissues hybridised with the Sox7 probe A. A major Sox7 mRNA band was detected at ∼4 kb. Positions of the ribosomal RNAs are indicated on the left (28S and 18S). Relative equal amounts of RNA were present in each lane as judged by examination of the ethidium bromide staining (lower panel showing 28S). (B) Detection of the human SOX7 transcript in poly(A)+ RNA samples from adult human tissues (hybridised with probe B). A major transcript ∼5 kb is detected in all lanes. Two additional transcripts of ∼2.5 kb are visible in adult colon and fetal lung. Lower panel shows rehybridisation with a β-actin probe.

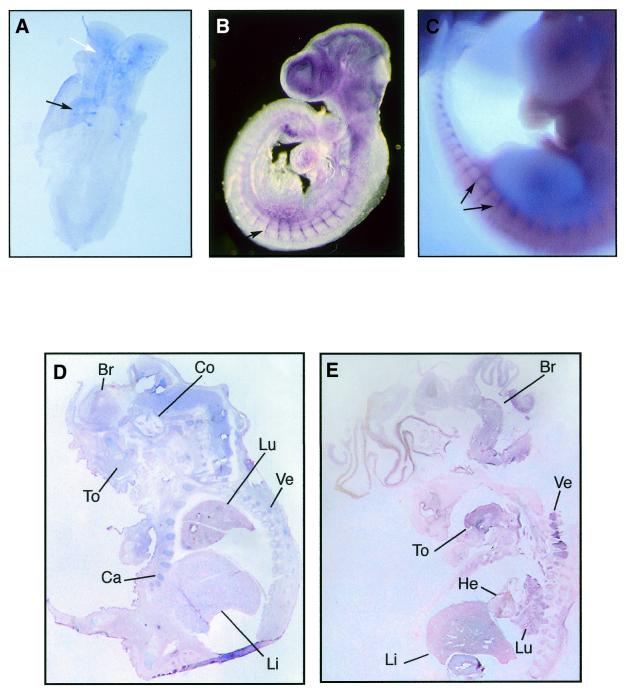

A series of in situ hybridisations to whole-mount mouse embryos from 8 to 11.5 d.p.c. and sections of 17.5 d.p.c. were performed. The 4-somite stage 8 d.p.c. mouse embryo shows expression of Sox7 in the somites and head regions (Fig. 3A). A remarkable expression of Sox7 was observed throughout the embryo vasculature at 9.5 d.p.c., and clearly marked in the intersomitic vessels (Fig. 3B). At 11.5 d.p.c., Sox7 expression appears primarily in the intersomitic vessels (Fig. 3C). Expressing Sox7 tissues are not stained with the sense probe (not shown). In the subsequent stages of development, Sox7 was expressed in restricted sites of the embryo. At 17.5 d.p.c., expression continues throughout the brain, cochlea, tongue, cartilage, lung, liver and vertebrae (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Mouse and human Sox7 expressions as revealed by in situ hybridisations. Whole-mount in situ hybridisations showing expression of Sox7 in the mouse developing embryo. (A) Ventral view of an 8 d.p.c. embryo (4-somite stage) revealing Sox7 expression in the somites (black arrow) and the brain (white arrow). (B) At 9.5 d.p.c., Sox7 expression is observed in the intersomitic vessels, along with the smaller vessels in the trunk and the head region. (C) At 11.5 d.p.c., expression persists in the intersomitic vessels (black arrows). Section in situ hybridisations comparing expressions of Sox7 in mouse and human embryos. (D) Sagittal section of 17.5 d.p.c. mouse embryo showing generalised Sox7 expression in brain (Br), cochlea (Co), tongue (To), lung (Lu), liver (Li), cartilage (Ca) and vertebrae (Ve). (E) Sagittal section of an 8 week-old (C.S.19) human embryo showing expression in brain, tongue, heart, lung, liver and vertebrae. Embryo sections in (D) and (E) are counterstained with nuclear fast red.

To observe the distribution of human embryonic SOX7 transcripts, we performed in situ hybridisation on 8 week-old human embryos. Sox7 mRNA is present in brain, tongue, heart, liver, lung and vertebrae (Fig. 3E). The control sense probe shows no staining on the same tissues (not shown).

Further in situ hybridisation analyses have revealed that Sox7 is present in both mesenchyme and epithelial layers of some adult tissues, such as mouse adult ear or human colon (data not shown).

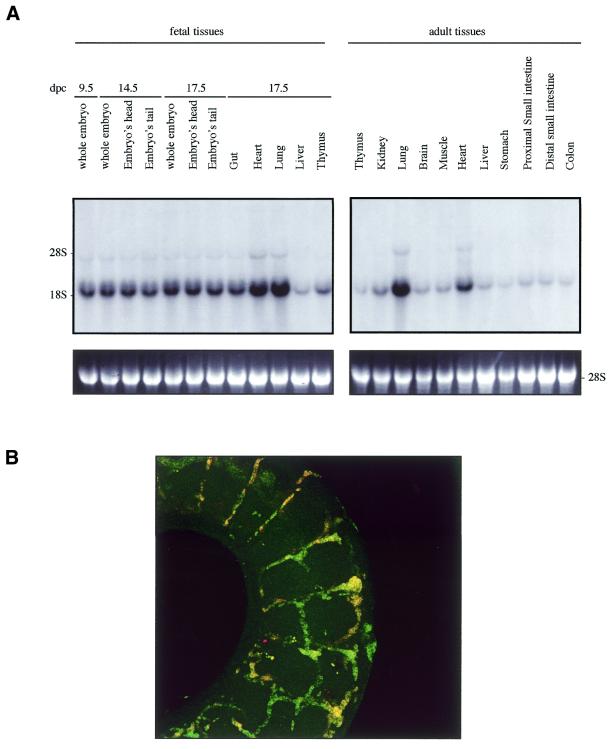

Comparison of mouse Sox7 and Sox18 expressions

The high degree of similarity between mouse Sox7 (this study) and Sox18 (17) expressions at 9.5 and 11.5 d.p.c. prompted us to compare their expressions in more detail. As shown in Figure 4A, probing of the embryonic and adult northern blots with a mouse Sox18-derived probe revealed a major band at ∼1.6 kb along with a very similar pattern to the one with a Sox7 probe seen in Figure 2A. Furthermore, in situ hybridisation experiments performed on whole embryos at the same stages (data not shown) (17) than those for the Sox7 probe confirmed this relative similarity. Furthermore, co-localisation of both mRNA expressions was tested and confirmed in the intersomitic vessels of 11.5 d.p.c. mouse embryos (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Mouse Sox18 expression. (A) Northern blots of total RNAs from various fetal and adult mouse tissues hybridised with the mouse Sox18. A major Sox18 mRNA band was detected at ∼1.6 kb. Positions of the ribosomal RNAs are indicated on the left (28S and 18S). Relative equal amounts of RNA were present in each lane as judged by examination of the ethidium bromide staining (lower panel showing 28S). (B) Colocalisation of Sox7 and Sox18 in the intersomitic vessels of the 11.5 d.p.c. mouse embryo. A dual colour FISH was performed using two combined labelled RNA probes: biotin-labelled Sox7 antisense probe (probe A) and digoxigenin-labelled Sox18 antisense probe.

Mouse SOX7 protein harbours a C-terminal transactivation domain

SOX proteins are characterised by their ability to bind to the DNA sequence motif 5′-(A/T)(A/T)CAA(A/T)G-3′ via their HMG domain. Previous electrophoretic shift assays indicated that the recombinant HMG box of mouse SOX7 binds to the AACAAT sequence (21). We therefore tested if SOX7 would be a transcriptional activator or repressor. Transcriptional regulation was examined with mouse SOX7 truncated constructs containing the HMG domain, but lacking different parts of the C-terminal region. The full-length SOX7 plasmid, as well as the various mutants were cloned into the Myc-tagged modified vector pGlomyc (30). Transfection experiments done in COS7 cells revealed that the full-length SOX7 (FLSox7) activates transcription by binding to a consensus DNA binding site present in the reporter plasmid SOXLUC, while mutants with deletions of the C-terminal domain of Sox7 failed to function as transcriptional activators (Fig. 5). Transcription activation domain was thus mapped within the C-terminus of the SOX7 protein. To show that deletions did not exclude SOX7 protein from the cell nucleus, SOX7 subcellular localisation was determined. COS7 cells transfected with the full-length or deleted Sox7 were processed for immunofluorescence using the anti-Myc antibody. Full-length or deleted SOX7 proteins were localised in the cell nucleus (data not shown), confirming as reported for other SOX proteins the presence of nuclear localisation signals within the HMG domain (31,32).

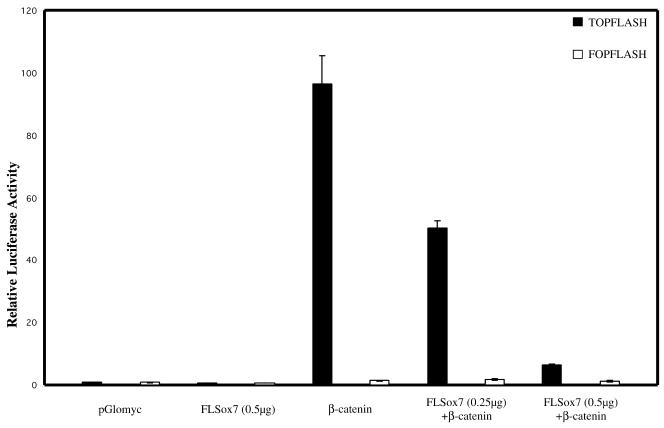

SOX7 protein represses Wnt/β-catenin-stimulated transcription

Recent data have suggested that different Xenopus SOX proteins could block β-catenin/TCF-mediated gene activation by competing with TCF factors for binding to β-catenin (33). We therefore tested if a mammalian SOX protein like SOX7 could also interfere with the Wnt signalling pathway. β-Catenin regulation of TCF activity is commonly measured using the TOPFLASH artificial reporter plasmid (34) in the human kidney 293 cell line that expresses endogenous TCF factors. It is noteworthy that transfection with SOX7 encoding plasmid alone does not stimulate transcription of the TOPFLASH reporter plasmid (data not shown). 293 cells were therefore cotransfected with the reporter construct TOPFLASH, along with the expression plasmid encoding a mutant form of β-catenin (β-cateninS33) leading to constitutive activation of β-catenin-TCF target genes, and with increasing plasmid concentrations encoding the full-length SOX7 protein. Transactivation of the luciferase reporter appears clearly to be repressed in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of FLSox7 construct (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

SOX7 inhibits β-catenin activation of the luciferase reporter. 293 Cells were cotransfected in the presence or absence of the mouse FLSox7 (0.25 µg and 0.5 µg), β-cateninS33 (0.1 µg) and TOPFLASH or FOPFLASH reporter plasmids (0.5 µg). TOPFLASH plasmid consists of three TCF binding sites upstream of the c-fos minimal promoter and the firefly luciferase coding region and FOPFLASH plasmid has mutated TCF binding motifs. The two negative controls used are the empty pGlomyc and the FOPFLASH. A representative experiment of three separate experiments is shown.

DISCUSSION

Members of the SOX gene family are important for many developmental processes (3). However, their functional importance has not been fully determined. In the present work, we have isolated the complete coding sequence of human SOX7 and compared the encoded protein to the previously described mouse orthologue. The high sequence similarity observed between mouse and human SOX7 proteins suggests conservation of their respective functions. SOX7, SOX18 and SOX17, which belong to the same F subgroup, have conserved intron positions suggesting that those genes had a common ancestor (14).

Northern experiments in both species revealed the presence of a major transcript in various fetal and adult tissues analysed, although with different intensities. Transcripts were observed in brain, heart, lung, kidney, prostate, colon and spleen. In situ hybridisation analysis shows expression of Sox7 mRNA, at the 4-somite stage 8 d.p.c., in the somites and head regions. Then, in stages of 9.5 and 11.5 d.p.c., Sox7 expression was observed in small branching vessels and mainly associated with intersomitic vessels, and later during development at 17.5 d.p.c., expression was clearly detected in brain, cochlea, tongue, lung, liver, cartilage and vertebrae. Human expression tested at only one embryonic stage (8 week-old) gives comparable results with the latest mouse prenatal stage analysed. Intriguingly, expression of Sox7 in embryonic organs such as liver, lung and heart where epithelio-mesenchymal transitions take place might suggest its possible involvement in this particular process. Sox7 mRNA was detected in many tissues where Sox18 gene expression has been previously described (17). Indeed, in mouse, northern blots confirm almost the same expression profiles for Sox7 and Sox18 in most tested fetal and adult tissues, and in situ hybridisation shows embryonic expression co-localisation of both genes mainly throughout the embryonic vasculature, but not in the hair follicles (data not shown) where Sox18 is strongly expressed. Their high sequence homology within the HMG box, and the relative similarity of their embryonic expression profiles suggest that Sox7 and Sox18 genes might have some overlapping functions in the corresponding tissues. This observation could support the mild defect recently reported after analysis of Sox18 knockout mice (18). The putative redundancy of different SOX proteins has been previously suggested in other developmental situations (3).

To date, human SOX7 sequence has not been released by the human genome project, and its chromosomal localisation was still unknown. Using FISH analysis, we could assign the gene location on the short arm of chromosome 8 (8p22) in human and on band D of chromosome 14 in mouse. For its more precise human chromosomal localisation, using the genetic marker STSG29953, we located the gene between D8S518 and D8S277 microsatellite markers within a genomic region containing some candidate genes of diverse syndromes, such as the maternally inherited deafness (OMIM no. 561000) and the microcephaly primary autosomal recessive 1 (OMIM no. 251200). SOX7 gene is thus added to the short list of genes located in this genomic interval.

SOX proteins so far analysed can act as either activators or repressors of transcription (19). We demonstrated that SOX7 protein is a potent activator. This domain falls at the C-terminal end as the transactivation domain of SOX17, another member of the F subgroup implicated in endoderm development in Xenopus (33), its exact location remains to be further investigated. Transfection experiments performed in 293 cells also showed the ability of SOX7 factor to repress TCF/β-catenin-stimulated transcription. The effect of SOX7 on the Wnt signalling pathway is in agreement with previous observations reported with SOX17.

Altogether, our data suggest that SOX7 transcription factor could act by using at least two different mechanisms, one involving target gene activation, and another involving regulation of the Wnt pathway by competing with TCF/LEF activity. In fact, different regulatory genes of the Wnt pathway are mutated in primary human cancers and several others promote cancer in experimental rodents. In all these cases, the common denominator is the activation of gene transcription by TCF/β-catenin (35). The capacity of SOX7 to inhibit TCF activity, and its chromosomal localisation on the short arm of chromosome 8, a chromosomal region that includes many described tumour suppressor genes inactivated in carcinogenesis (36), might suggest the possible role of SOX7 as a tumour suppressor gene. Since the possible link of SOX proteins to oncogenesis has been previously suggested (37,38), experiments are under way to test such a hypothesis.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Prof. Jacques Demaille for continuous support, to Dr Stephan Gasca for invaluable technical advice and helpful comments on the manuscript, to Dr Marie Vendromme for help and advice, and to Drs Arnaud Monteil and Francois Rassendren for sharing their northern blots. We thank Ms Brigitte Moniot for technical assistance, Mr Patrick Atger for photographic processing, Mrs N. Lautrédou for confocal microscopy. Special thanks to Prof. Peter Koopman for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the European Economic Community through the fifth framework Program no. GLG2-CT-1999-00741; ARC grant no. 5210 (to P.B.) and ARC grant no. 5310 (to P.J.). W.T. was funded by a région Languedoc-Roussillon graduate award.

DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AJ409320

References

- 1.Capel B. (2000) The battle of the sexes. Mech. Dev., 92, 89–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinclair A.H., Berta,P., Palmer,M.S., Hawkins,J.R., Griffiths,B.L., Smith,M.J., Foster,J.W., Frischauf,A.M., Lovell-Badge,R. and Goodfellow,P.N. (1990) A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature, 346, 240–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wegner M. (1999) From head to toes: the multiple facets of Sox proteins. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 1409–1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soullier S., Jay,P., Poulat,F., Vanacker,J.M., Berta,P. and Laudet,V. (1999) Diversification pattern of the HMG and SOX family members during evolution. J. Mol. Evol., 48, 517–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harley V.R., Lovell-Badge,R. and Goodfellow,P.N. (1994) Definition of a consensus DNA binding site for SRY. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 1500–1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grosschedl R., Giese,K. and Pagel,J. (1994) HMG domain proteins: architectural elements in the assembly of nucleoprotein structures. Trends Genet., 10, 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster J.W., Dominguez-Steglich,M.A., Guioli,S., Kwok,G., Weller,P.A., Stevanovic,M., Weissenbach,J., Mansour,S., Young,I.D. and Goodfellow,P.N. (1994) Campomelic dysplasia and autosomal sex reversal caused by mutations in an SRY-related gene. Nature, 372, 525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schafer A.J., Dominguez-Steglich,M.A., Guioli,S., Kwok,C., Weller,P.A., Stevanovic,M., Weissenbach,J., Mansour,S., Young,I.D., Goodfellow,P.N. et al. (1995) The role of SOX9 in autosomal sex reversal and campomelic dysplasia. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci., 350, 271–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Southard-Smith E.M., Kos,L. and Pavan,W.J. (1998) Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nature Genet., 18, 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pingault V., Bondurand,N., Kuhlbrodt,K., Goerich,D.E., Prehu,M.O., Puliti,A., Herbarth,B., Hermans-Borgmeyer,I., Legius,E., Matthijs,G. et al. (1998) SOX10 mutations in patients with Waardenburg–Hirschsprung disease. Nature Genet., 18, 171–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishiguchi S., Wood,H., Kondoh,H., Lovell-Badge,R. and Episkopou,V. (1998) Sox1 directly regulates the γ-crystallin genes and is essential for lens development in mice. Genes Dev., 12, 776–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schilham M.W., Oosterwegel,M.A., Moerer,P., Ya,J., de Boer,P.A., van de Wetering,M., Verbeek,S., Lamers,W.H., Kruisbeek,A.M., Cumano,A. and Clevers,H. (1996) Defects in cardiac outflow tract formation and pro-B-lymphocyte expansion in mice lacking Sox-4. Nature, 380, 711–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagiwara N., Klewer,S.E., Samson,R.A., Erickson,D.T., Lyon,M.F. and Brilliant,M.H. (2000) Sox6 is a candidate gene for p100H myopathy, heart block, and sudden neonatal death. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 4180–4185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowles J., Schepers,G. and Koopman,P. (2000) Phylogeny of the SOX family of developmental transcription factors based on sequence and structural indicators. Dev. Biol., 227, 339–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson C., Clements,D., Friday,R.V., Stott,D. and Woodland,H.R. (1997) Xsox17α and -β mediate endoderm formation in Xenopus. Cell, 91, 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanai Y., Kanai-Azuma,M., Noce,T., Saido,T.C., Shiroishi,T., Hayashi,Y. and Yazaki,K. (1996) Identification of two Sox17 messenger RNA isoforms, with and without the high mobility group box region, and their differential expression in mouse spermatogenesis. J. Cell Biol., 133, 667–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pennisi D., Gardner,J., Chambers,D., Hosking,B., Peters,J., Muscat,G., Abbott,C. and Koopman,P. (2000) Mutations in Sox18 underlie cardiovascular and hair follicle defects in ragged mice. Nature Genet., 24, 434–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennisi D., Bowles,J., Nagy,A., Muscat,G. and Koopman,P. (2000) Mice null for sox18 are viable and display a mild coat defect. Mol. Cell Biol., 20, 9331–9336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchikawa M., Kamachi,Y. and Kondoh,H. (1999) Two distinct subgroups of group B Sox genes for transcriptional activators and repressors: their expression during embryonic organogenesis of the chicken. Mech. Dev., 84, 103–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiozawa M., Hiraoka,Y., Komatsu,N., Ogawa,M., Sakai,Y. and Aiso,S. (1996) Cloning and characterization of Xenopus laevis xSox7 cDNA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1309, 73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taniguchi K., Hiraoka,Y., Ogawa,M., Sakai,Y., Kido,S. and Aiso,S. (1999) Isolation and characterization of a mouse SRY-related cDNA, mSox7. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1445, 225–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonhomme F. and Guénet,J.L. (1989) The wild house mouse and its relative. In Lyon,M.F. and Searle,A.G. (eds), Genetic Variants and Strains of the Laboratory Mouse, 2nd Edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 649–662.

- 23.Matsuda Y., Harada,Y.N., Natsuume-Sakai,S., Lee,K., Shiomi,T. and Chapman,V.M. (1992) Location of the mouse complement factor H gene (cfh) by FISH analysis and replication R-banding. Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 61, 282–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinkel D., Straume,T. and Gray,J.W. (1986) Cytogenetic analysis using quantitative, high-sensitivity, fluorescence hybridization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 83, 2934–2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lemieux N., Dutrillaux,B. and Viegas-Pequignot,E. (1992) A simple method for simultaneous R- or G-banding and fluorescence in situ hybridization of small single-copy genes. Cytogenet. Cell Genet., 59, 311–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilkinson D.G. and Nieto,M.A. (1993) Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods Enzymol., 225, 361–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Rahilly R. (1983) The timing and sequence of events in the development of the human endocrine system during the embryonic period proper. Anat. Embryol., 166, 439–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venter J.C., Adams,M.D., Myers,E.W., Li,P.W., Mural,R.J., Sutton,G.G., Smith,H.O., Yandell,M., Evans,C.A., Holt,R.A. et al. (2001) The sequence of the human genome. Science, 291, 1304–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blake J.A., Eppig,J.T., Richardson,J.E. and Davidson,M.T. (2000) The Mouse Genome Database Group (MGD): expanding genetic resources for the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res., 28, 108–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roose J., Korver,W., Oving,E., Wilson,A., Wagenaar,G., Markman,M., Lamers,W. and Clevers,H. (1998) High expression of the HMG box factor sox-13 in arterial walls during embryonic development. Nucleic Acids Res., 26, 469–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poulat F., Girard,F., Chevron,M.P., Gozé,C., Rebillard,X., Calas,B., Lamb,N. and Berta,P. (1995) Nuclear localization of the testis determining gene product SRY. J. Cell Biol., 5, 737–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Südbeck P. and Scherer,G. (1997) Two independent nuclear localization signals are present in the DNA-binding high mobility group domains of SRY and SOX9. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 27848–27852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zorn A.M., Barish,G.D., Williams,B.O., Lavender,P., Klymkowsky,M.W. and Varmus,H.E. (1999) Regulation of Wnt signaling by Sox proteins: Xsox17α/β and Xsox3 physically interact with β-catenin. Mol. Cell, 4, 487–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korinek V., Barker,N., Morin,P.J., van Wichen,D., de Weger,R., Kinzler,K.W., Vogelstein,B. and Clevers,H. (1997) Constitutive transcriptional activation by a beta-catenin-Tcf complex in APC–/– colon carcinoma. Science, 275, 1784–1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polakis P. (2000) Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev., 14, 1837–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy A., Dang,U.C. and Bookstein,R. (1999) High-density screen of human tumor cell lines for homozygous deletions of loci on chromosome arm 8p. Genes Chromosom. Cancer, 24, 42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia Y., Papalopulu,N., Vogt,P.K. and Li,J. (2000) The oncogenic potential of the high mobility group box protein Sox3. Cancer Res., 60, 6303–6306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tani M., Shindo-Okada,N., Hashimoto,Y., Shiroishi,T., Takenoshita,S., Nagamachi,Y. and Yokota,J. (1997) Isolation of a novel Sry-related gene that is expressed in high-metastatic K-1735 murine melanoma cells. Genomics, 39, 30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]