Abstract

Objective:

Exposure to sexual assault results in ongoing harms for women. After an assault, some women engage in higher levels of externalizing behaviors, such as problem drinking, and others experience higher levels of internalizing dysfunction, such as symptoms of anxiety and depression. We sought to understand the role of premorbid factors on the different post-assault experiences of women.

Method:

We studied 1,929 women prospectively during a period of high risk for sexual assault (the first year of college): women were assessed in July before arriving at college and in April near the end of the school year.

Results:

A premorbid personality disposition to act impulsively when distressed (negative urgency) interacted positively with sexual assault experience to predict subsequent increases in drinking behavior; a premorbid personality disposition toward internalizing dysfunction positively interacted with sexual assault experience to predict increased symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Conclusions:

Women with different personalities tend to experience different forms of post-assault consequences.

Sexual assault, sexual acts that are perpetrated against a person’s will or when a person is incapable of giving consent (U.S. Department of Education, 2011), is known to have a significant impact on the mental health of assaulted women. One important and, as of yet, unexplained phenomenon is that some women respond to the trauma of sexual assault with symptoms of externalizing disorders, most notably heavy alcohol consumption, whereas others respond to trauma with increases in internalizing dysfunction, such as major depression and generalized anxiety disorder (Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Ullman et al., 2013). It is crucial to be able to identify which women are likely to respond to sexual trauma in which way, given that (a) heavy alcohol consumption is associated with many problems and (b) there are different empirically supported treatments for different kinds of dysfunction (Hayes et al., 1999; Linehan, 1993).

The intent of this study was to test whether pre-assault personality characteristics interact with sexual trauma to predict differential outcomes. Findings in support of this model suggest the value of applying different interventions to different assault victims, based on their personality characteristics.

The highest estimates of sexual assault are found in women ages 16–24 years, who are four times as likely to be sexually assaulted as any other age group (Danielson & Holmes, 2004). Major maladaptive outcomes of sexual assault are drinking problems, clinical anxiety, and clinical depression. These outcomes can be understood to reflect externalizing dysfunction (drinking problems) and internalizing dysfunction (clinical anxiety, clinical depression; Krueger & Markon, 2006).

Outcomes following sexual assault

Externalizing dysfunction.

Sexual assault is consistently associated with maladaptive drinking behavior. Reports of alcohol dependence in women post-assault range from 13% to 49% (Petrak et al., 1997). College student and other adult sexual abuse survivors report more overall drinking after assault as well as more drinking problems than other women (Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2011; Blayney et al., 2016; Griffin et al., 2013; Ullman & Najdowski, 2009). Of course the responsibility of engaging in sexual assault rests with the perpetrator, but increased use of substances is of particular note because such use increases risk for re-victimization (Littleton & Ullman, 2013; Ullman & Najdowski, 2009). The identification of factors that lead to such high-risk behaviors after an assault experience may facilitate more effective care for assault survivors.

Internalizing dysfunction.

Sexual assault is also highly associated with subsequent anxiety and depressive disorders (Breslau, 2002, Frazier et al., 2009). Reportedly, 13%–51% of women develop depression after an assault, whereas 73%–82% develop fear and/or anxiety symptoms (Acierno et al., 2002; Clum et al., 2000). If a post-assault expression of anxiety is to go out less, stay home, and perhaps have less social interaction, one result is reduced access to positive reinforcement and social support (e.g., Hopko et al., 2003). Such reduced access can serve to suppress positive affect. Individuals who are experiencing distress and negative affect, but reduced positive affect, are likely to experience higher levels of depressive symptomatology.

Personality correlates of substance use and anxiety and depression.

The fact that only a portion of women who have experienced a sexual trauma go on to develop substance abuse problems, and only a portion experience heightened anxiety and depression symptoms, suggests that there are important individual differences contributing to risk for those negative sequelae to sexual trauma. One source of such individual differences may be personality. The trait of negative urgency, the tendency to act rashly when distressed (Cyders & Smith, 2008; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001), predicts substance abuse and other externalizing behavioral dysfunction (Fischer et al., 2013; Settles et al., 2010; Smith & Cyders, 2016). In contrast, personality dispositions to respond to events in anxious or depressive ways (trait anxiety and trait depression) predict the development of symptoms of clinical anxiety and clinical depression (Hettema et al., 2006; Settles et al., 2012). Perhaps elevations in one or the other of these traits increase the likelihood of externalizing or internalizing behavioral responses to trauma.

Current study

To assess personality before sexual assault exposure, we followed women across their first year of college, a period in which approximately 17% of women experience some form of sexual assault (Wilcox et al., 2007). We assessed 1,929 women before they began their first year of college and again near the end of that first year. This sample included both women who were first assaulted during the first year of college and women who were assaulted before college and experienced re-victimization over the course of the year.

We tested two hypotheses with regard to interactions between personality and the experience of sexual assault: (a) Negative urgency would interact with sexual assault to predict increased alcohol consumption across the first year, above and beyond the effect of initial alcohol use. In contrast, (b) trait depression and anxiety would interact with assault victimization to predict increases in symptoms of clinical depression and anxiety across the first year of college. The interaction between negative urgency and sexual assault would not predict increased internalizing dysfunction.

A prior cross-sectional study (Combs et al., 2014) found the hypothesized associations to be present at one point in time. There are advantages to testing these associations using a longitudinal design. First, we can measure personality before the experience of sexual assault for those not previously victimized. Second, we can test for the modifying effects of prior sexual assault. Third, we can control for prior drinking or internalizing symptoms and thus test whether personality interacts with sexual assault to predict changes in symptom levels.

We tested whether each of these effects varied as a function of whether women were experiencing their first assault or re-victimization. There is evidence for negative sequelae to both first assaults and repeated assault among adolescent and adult women (Walsh et al., 2014). In general, multiple traumas exacerbate negative outcomes (Ullman & Najdowski, 2009). However, those in our sample with a sexual assault history may not be fully representative of women with such a history because we studied only college students. For example, it may be the case that a higher percentage of women who enter college were fortunate enough to receive support or intervention following the trauma. Therefore, we had no a priori hypotheses as to whether effects would vary based on the number of assaults experienced.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited the summer before their freshman year of college to participate in a longitudinal study. We limited the participant sample to women entering college within 3 years of graduating high school. The sample participated at two different time points: the month before the school year began (July) and near the end of the freshman year (April). The mean age of participants at the initiation of the study was 18.04 years. Most participants were European American (88.1%) and identified as heterosexual/straight (96.7%).

Procedure

Time 1.

The Time 1 assessment took place in July before the participants’ first day of move-in. We sent an e-mail to all incoming female freshmen with instructions on accessing the online survey system. Eligibility was determined by questions regarding gender, nature of enrollment, and Englishspeaking ability. On completion, participants were entered in a raffle to win one of eight $250 gift cards to Target.

Time 2.

The Time 2 assessment took place in late April of the participants’ freshman year; participants were paid $10 for their participation. Participants completed the same group of measures with modifications to assess exposure to sexual assault, problem drinking, and symptoms of anxiety/depression for the period of the academic year. All participants received information about various ways to receive help from community or university clinics; those who disclosed a history of sexual assault received additional reminders about community resources.

Measures

Demographic information.

The participants filled out a demographic questionnaire providing information on estimated household income, age, ethnicity, parents’ education, and sexual orientation.

Sexual Experiences Survey.

The Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss & Oros, 1982) is a 14-item measure of different dimensions of sexual assault and rape. The experiences asked about a range of sexual assault experiences, from unwanted touching to rape with a foreign object, and the questions asked about the participant’s age at which the experience occurred and the number of times the experience occurred. For Time 1, the SES asked about any incidents that occurred between age 14 years and the current age of the participant. Time 2 asked if any assaults had occurred between Time 1 (July) and the present (April); it assessed in which specific month the assault occurred. The SES is consistent with verbal reports of victimization at r = .73 (Koss & Gidycz, 1985). A revised version of the SES was published in 2007 (Koss et al., 2007), but we used the original version because, to date, it rests on a more extensive body of validity evidence. We did modify the SES by adjusting the wording of some items to reduce the level of responsibility placed on the potential victims; for example, the phrase “sex play” was removed in favor of strict behavioral descriptions (“fondling, touching, petting”), and questions referring to intoxication were edited to reflect the possibility that the respondent was intoxicated before initially encountering an assailant (rather than mandating that the assailant provided alcohol/other drugs to the respondent in order to qualify as assault). These changes are consistent with revisions made to the SES.

There is good evidence for the convergent validity of different scoring methods of the SES (Davis et al., 2014). Because the current sample was a nonselected sample with a low base rate of assault experiences, we scored the total number of sexual assaults experienced by the participant across the first year of college. As we describe below, these data were highly positively skewed. We describe analytic decisions made based on the skewness of these results later in this section.

Drinking Styles Questionnaire.

We constructed a standard quantity/frequency (QF) index by summing the responses to two items in the Drinking Styles Questionnaire (Smith et al., 1995) that were responded to in relation to drinking frequency and quantity during the current month. There is considerable evidence for the internal consistency, stability over time, and validity of this measure (cf. Settles et al., 2010). Coefficient alpha in this sample was .87 at Time 1 and .90 at Time 2. We measured QF for the current month in July, before the start of freshman year, and in April, at the end of freshman year.

Beck Depression Inventory-II.

The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) is a self-report measure that consists of 21 items used to assess depressive symptoms. In this sample, the reliability of the scale was .93 at Time 1 and .98 at Time 2.

Beck Anxiety Inventory.

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990) is a 21-item measure of different symptoms of anxiety. In this sample, the reliability of the scale was .94 at Time 1 and .97 at Time 2.

UPPS-P Impulsivity Scale: Negative Urgency Subscale.

The UPPS-P Impulsivity Scale: Negative Urgency Subscale (Lynam et al., 2006) (12 Likert-type items) was administered at Time 1 (α = .89). Negative urgency can be understood as the tendency to perform rash acts while in a negative mood.

Revised NEO Personality Inventory, Trait Depression and Trait Anxiety Scales.

Trait depression and trait anxiety were measured at Time 1 with eight items each from the Revised NEO Personality Inventory, Trait Depression and Trait Anxiety Scales (NEO-PI-R; Costa & McCrae, 1992) and are part of the Neuroticism domain of personality (α = .83 and .75, respectively, and when combined, α = .86.). Because the two scales were so highly correlated (r = .62), and because when treated individually the two scales produced the same results in all of the analyses described below, we combined them.

Data analysis

Model tests.

We tested the central hypotheses using regression models in IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The predictor variables were as follows: Step 1: personality (negative urgency and trait anxiety/depression measured at Time 1; both variables centered); sexual assault occurring between August and March of freshman year (SA); sexual assault history before college (SAHx); and report of each outcome variable in the month before college began (QF in July and symptoms of clinical anxiety/depression in July). Step 2: interaction terms for SA × negative urgency, SA × trait anxiety/depression, SA × SAHx, SAHx × negative urgency, and SAHx × trait anxiety/depression. Step 3: three-way interaction terms for negative urgency × SA × SAHx and trait anxiety/depression × SA × SAHx. We probed interactions using computational tools provided by Preacher et al. (2006). We present interactions by plotting one standard deviation above and below the mean for centered interval scale and using 0 or 1 for dichotomous variables.

Treatment of missing data.

There was no significant effect for missingness: retained and nonretained participants did not differ on any study variables. Because listwise and pairwise deletion of missing data produces biased population parameter estimates (Allison, 2003; Enders & Peugh, 2004), we used expectation maximization (EM), a maximum likelihood process, to impute values for missing cases using SPSS. This method is a single imputation procedure. Although single imputation has historically produced underestimates of standard errors, the SPSS procedure includes a correction to the standard error to avoid/reduce this problem. Use of EM procedures has been shown to produce parameter estimates accurate to within two decimal points and of equal accuracy to full-information maximum likelihood methods (Enders & Peugh, 2004).

Results

Retention, descriptive statistics, and measurement of sexual assault

The retention rate was 63% from Time 1 to Time 2, which is comparable to most longitudinal studies of sexual assault (average rate = 70%; Campbell et al., 2011). Descriptive statistics for sexual assault broken down by those who had been previously assaulted and those who had not are displayed in Table 1. Of those women who reported that they had not experienced an assault before college, 14.0% reported experiencing an unwanted sexual event during the school year (August through March). A total of 553 women (28.67% of the sample) reported having been sexually assaulted before college. Of those, 31.8% reported experiencing an unwanted sexual event during the school year, which is a higher frequency than for those with no assault history, χ2(1) = 80.79, p < .001. Descriptive statistics of outcome variables and bivariate correlations between key study variables can be found in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of reported sexual assault data across freshman year (August through April)

| Sexual assault across freshman year | Reported no history of assault before college (n = 1,376) | Reported history of assault before college (n = 553) |

| Reported no sexual assault | 86.0% (n = 1,183) | 68.2% (n = 377) |

| Unwanted touching | 12.2% (n = 168) | 29.1% (n = 161) |

| Attempted sex | 3.5% (n = 48) | 7.8% (n = 43) |

| Pressured/coerced sex | 2.5% (n = 34) | 9.8% (n = 54) |

| Forced rape | 2.5% (n = 35) | 6.7% (n = 38) |

Notes: These numbers and percentages represent the number of people who experienced this type of sexual assault at all during their first year, as a dichotomous variable. Individuals who experienced more than one type of sexual assault are represented in multiple categories; thus, the percentages add up to more than 100%.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of outcome variables (drinking quantity/frequency and clinical anxiety/depression symptom count)

| Variable | T1 drink QF | T2 drink QF | T1 BDI/BAI | T2 BDI/BAI | T1 NU | T1 NEO |

| Reported no history of assault before college (n = 1,376) | ||||||

| Mean | 2.71 | 3.91 | 9.22 | 6.44 | 2.01 | 2.74 |

| Variance | 3.86 | 4.75 | 137.23 | 122.27 | 0.24 | 0.33 |

| Range | 0–8 | 0–9 | 0–92 | 0–94 | 1–3.84 | 1–4.81 |

| Reported history of assault before college (n = 553) | ||||||

| Mean | 3.89 | 4.31 | 19.19 | 10.39 | 2.33 | 2.98 |

| Variance | 4.82 | 4.06 | 387.29 | 285.85 | 0.37 | 0.40 |

| Range | 0–8 | 0–9 | 0–101 | 0–116 | 1–4 | 1–4.75 |

Notes: N = 1,929. T1 drink QF = drinking quantity frequency, Time 1, July; T2 drink QF = drinking quantity frequency, T2, April; T1 BDI/BAI = composite score of results on Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), T1, July; T2 BDI/BAI = composite score of results on BAI and BDI, T2, April; NU = negative urgency levels; NEO = scores on the trait anxiety/depression measure. The range for drinking frequency and quantity represents a sum total of participant responses to questions about their drinking habits. A 9 represents the highest level of drinking seen in this population; this person would report drinking a lot of alcohol almost daily. The range for clinical anxiety/depression represents the sum total of responses on measure of anxiety and depression. A person who received a 116 likely rated all anxiety and depression symptoms as being severe. Negative urgency and trait anxiety/depression are both moderators, and are thus reported at Time 1 only.

Table 3.

Correlations between key study variables

| T1 NU | T1 NEO | T1 drink QF | T2 drink QF | T1 BDI/BAI | T2 BDI/BAI | SA history | |

| T1 NU | |||||||

| T1 NEO | .52** | ||||||

| T1 drink QF | .23** | .00 | |||||

| T2 drink QF | .13** | -.04 | .46** | ||||

| T1 BDI/BAI | .43** | .58** | .06** | -.04 | |||

| T2 BDI/BAI | .20** | .33** | .01 | -.04 | .42** | ||

| SA history | .27** | .18** | .25** | .09** | .30** | .17** | |

| SA college | .09** | .09** | .14** | .14** | .12** | .17** | .21** |

Notes: T1 drink QF = drinking quantity frequency, Time 1, July; T2 drink QF = drinking quantity frequency, T2, April; T1 BDI/BAI = composite score of results on Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), T1, July; T2 BDI/BAI = composite score of results on BAI and BDI, T2, April; NU = negative urgency levels; NEO = scores on the trait anxiety/depression measure; SA history = reported sexual assault before college; SA college = reported sexual assault in college. Negative urgency and trait anxiety/depression are both moderators, and are thus reported at Time 1 only.

p < .01.

Given the high levels of skew and kurtosis in the measurement of sexual assault, we present our main hypothesis test results using sexual assault experiences as a dichotomous variable: a 1 was assigned to any instance of unwanted touching, coerced/forced attempted intercourse, and coerced/forced intercourse and a 0 was assigned when no such instances were reported. We analyzed the sexual assault data in two additional ways. First, we coded scores into three categories reflecting the number of sexual assault experiences: 0 = no reported assaults (n = 1,560, 80.9%), 1 = one reported sexual assault experience (n = 133, 6.9%), and 2 = more than one reported sexual assault in the first year of college (n = 236, 12.2% of the sample). We found no statistically significant differences between having experienced one assault or multiple assaults with regard to our main hypothesis tests. Second, we ran the same models treating the number of sexual assaults as an interval scale. Whether we then transformed the data to reduce skew (we ran square root and fourth root transformations) or analyzed the skewed data without transformation, we found virtually the same effects as we found when treating assault experience dichotomously.

Hypothesis 1

The first hypothesis was that the effect of negative urgency on drinking QF will be stronger among those having experienced sexual assault. This hypothesis was supported: The significant, positive main effects for negative urgency and assault experience in predicting increased drinking QF were modified by an interaction between the two (Table 4). As shown in Figure 1, for those women who were assaulted during the first year of college, the association between negative urgency and drinking QF was significantly greater than zero, slope = .86, t(358) = 3.37, p < .001. The slope relating negative urgency to drinking QF for women not assaulted was nonsignificant, slope = .23, t(1549) = 1.81, p = .07. The women who reported the highest levels of drinking were those who had been assaulted and had high levels of negative urgency. The number of women in each quadrant of the interaction is provided in the Figure 1 caption.

Table 4.

Linear regression results for prediction of drinking QF scores at Time 2

| Variable | B | SE B | t | Significance | [95% CI] | R2 |

| Final step | .23 | |||||

| T1 NU | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.79 | .074 | [-0.02, 0.48] | |

| T1 NEO | -0.09 | 0.11 | -0.87 | .387 | [-0.31, 0.12] | |

| SA history | -0.13 | 0.12 | -1.10 | .271 | [-0.37, 0.10] | |

| SA college | 0.56 | 0.15 | 3.79 | .000 | [0.27, 0.85] | |

| T1 drink QF | 0.45 | 0.02 | 20.57 | .000 | [0.41, 0.49] | |

| SA college × T1 NU | 0.63 | 0.25 | 2.54 | .011 | [0.14, 1.12] | |

| SA college × T1 NEO | -0.46 | 0.22 | -2.10 | .035 | [-0.89, -0.03] | |

| SA college × SA history | -0.17 | 0.23 | -0.72 | .474 | [-0.63, 0.29] | |

| SA history × T1 NU | -0.20 | 0.20 | -0.97 | .333 | [-0.60, 0.20] | |

| SA history × T1 NEO | -0.30 | 0.18 | -1.64 | .101 | [-0.66, 0.06] |

Notes: Bold indicates predictors significant at the .05 level. CI = confidence interval; T1 = Time 1 (July); NU = negative urgency levels; NEO = scores on the trait anxiety/depression measure; SA history = reported sexual assault before college; SA college = reported sexual assault in college; drink QF = composite score of drinking quantity and drinking frequency. Step 2, the final step of the regression model, is presented.

Figure 1.

Prediction of changes in drinking quantity and frequency (QF) by the interaction of negative urgency and freshman year sexual assault experience. Negative urgency scores are plotted 1 SD above and below the mean, and sexual assault experience is coded dichotomously. For women who were sexually assaulted, the mean drinking QF increase from low to high levels of negative urgency was 1 point on the 9-point scale. Examples of a 1-point increase would be increasing drinking frequency from monthly to once or twice a week, or increasing drinking quantity from 1 beer or 1 drink or less to between 2 and 3 beers or drinks. For women who were not sexually assaulted, the change was very small. Participant frequency by quadrant is as follows: above the mean on negative urgency/positive for sexual assault n = 179; above the mean on negative urgency/negative for sexual assault n = 599; below the mean on negative urgency/positive for sexual assault n = 190; below the mean on negative urgency/negative for sexual assault n = 961.

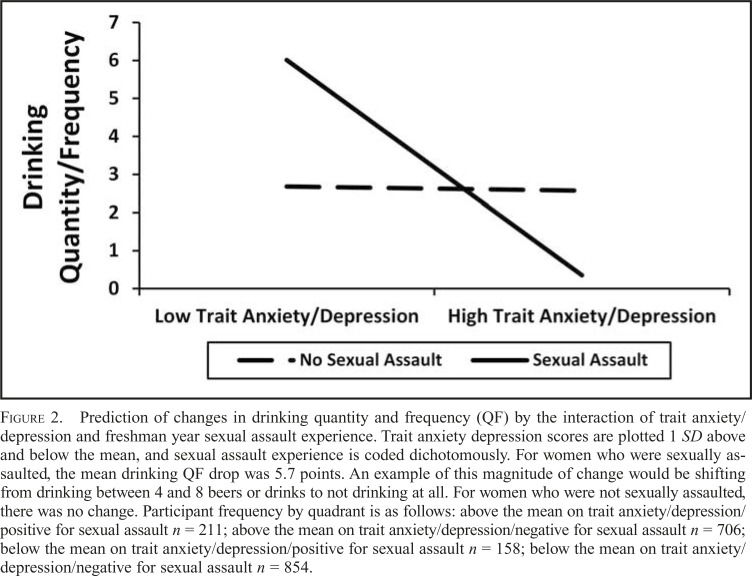

Unexpectedly, when we controlled for the direct effects and the Negative Urgency × Sexual Assault interaction, there was a crossover interaction between trait anxiety/depression and assault experience in predicting drinking QF (Table 4). As shown in Figure 2, among those women who were assaulted freshman year, elevations in the trait predicted lower levels of drinking behavior than for women low on the trait, simple effects slope = -4.71, t(358) = -21.74, p < .001. For women who were not assaulted, there was no evidence of a relationship between trait levels and drinking QF, simple effects slope = -.09, t(1549) = 0.90, p = .37. The number of women in each quadrant of the interaction is provided in the Figure 2 caption.

Figure 2.

Prediction of changes in drinking quantity and frequency (QF) by the interaction of trait anxiety/depression and freshman year sexual assault experience. Trait anxiety depression scores are plotted 1 SD above and below the mean, and sexual assault experience is coded dichotomously. For women who were sexually assaulted, the mean drinking QF drop was 5.7 points. An example of this magnitude of change would be shifting from drinking between 4 and 8 beers or drinks to not drinking at all. For women who were not sexually assaulted, there was no change. Participant frequency by quadrant is as follows: above the mean on trait anxiety/depression/positive for sexual assault n = 211; above the mean on trait anxiety/depression/negative for sexual assault n = 706; below the mean on trait anxiety/depression/positive for sexual assault n = 158; below the mean on trait anxiety/depression/negative for sexual assault n = 854.

None of the effects were modified by whether women had experienced an assault before college. We therefore have no basis for concluding that the joint effects of sexual assault and the traits studied operate differently for first assault sufferers and those experiencing re-victimization.

Hypothesis 2

The second hypothesis was that trait depression and anxiety would interact with assault victimization to predict increases in symptoms of clinical depression and anxiety across the first year of college. As shown in Table 5 and Figure 3, this hypothesis was supported. For women who were assaulted sexually during freshman year, trait anxiety/depression significantly predicted increases in symptoms of clinical anxiety/depression, slope = 5.74, t(358) = 3.25, p < .001, and more strongly than for women who were not assaulted, for whom the relationship was still positive, slope = 1.85, t(1549) = 2.60, p < .01. The women who reported the most anxiety/depression symptoms were those who had been assaulted and had high levels of trait anxiety/depression. See the Figure 3 caption for the number of women in each quadrant of the interaction.

Table 5.

Linear regression results for BDI/BAI scores (anxiety/depression) at Time 2

| Variable | B | SE B | t | Significance | [95% CI] | R2 |

| Final step | .22 | |||||

| T1 NU | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.88 | .382 | [-0.88, 2.30] | |

| T1 NEO | 1.85 | 0.72 | 2.57 | .010 | [0.44, 3.27] | |

| SA history | 0.45 | 0.74 | 0.61 | .545 | [-1.00, 1.90] | |

| SA college | 3.36 | 0.91 | 3.70 | .000 | [1.58, 5.14] | |

| T1 BDI/BAI | 0.28 | 0.02 | 12.16 | .000 | [0.23, 0.33] | |

| SA college × T1 NU | -2.96 | 2.21 | -1.34 | .180 | [-7.30, 1.37] | |

| SA college × T1 NEO | 3.89 | 1.91 | 2.04 | .042 | [0.15, 7.64] | |

| SA college × SA history | -1.85 | 1.47 | -1.25 | .210 | [-4.74, 1.04] | |

| SA history × T1 NEO | -4.84 | 1.42 | -3.42 | .001 | [-7.61, -2.06] | |

| SA history × T1 NEO | 0.99 | 1.29 | 0.77 | .445 | [-1.54, 3.52] | |

| SA college × T1 NU × SA history | 10.67 | 3.07 | 3.48 | .001 | [4.66, 16.68] | |

| SA college × T1 NEO × SA history | 1.21 | 2.71 | 0.45 | .656 | [-4.11, 6.53] |

Notes: Bold indicates predictors significant at the .05 level. CI = confidence interval; T1 = Time 1 (July); NU = negative urgency levels; NEO = scores on the trait anxiety/depression measure; SA history = reported sexual assault before college, SA college = reported sexual assault in college; BDI/BAI = composite score of results on Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Step 3, the final step of the regression model, is presented.

Figure 3.

Prediction of changes in anxiety/depression symptoms by the interaction of trait anxiety/depression and freshman year sexual assault experience. Trait anxiety depression scores are plotted 1 SD above and below the mean, and sexual assault experience is coded dichotomously. For women who were sexually assaulted, the mean increase in symptoms endorsed is 6.4. An example of a change of this magnitude would be increasing the frequency of between 6 and 7 symptoms from 1–2 days in the preceding week to 3–4 days in the preceding week. For women who were not assaulted, there was a mean increase in symptoms of 2.4. Participant frequency by quadrant is as follows: above the mean on trait anxiety/depression/positive for sexual assault n = 211; above the mean on trait anxiety/depression/negative for sexual assault n = 706; below the mean on trait anxiety/depression/positive for sexual assault n = 158; below the mean on trait anxiety/depression/negative for sexual assault n = 854.

We had anticipated no association between negative urgency and assault experience in predicting increases in anxiety/depression symptoms. We did, however, observe a three-way interaction among negative urgency, sexual assault experience during freshman year, and pre-college assault history (Table 5). As shown in Figure 4, for women with a pre-college history of sexual assault, after we controlled for main effects and the interaction of trait anxiety/depression, elevations in negative urgency predicted increased anxiety/depression symptoms for women who were assaulted again freshman year, slope = 3.58, t(162) = 2.03, p < .05, and no significant change for those who were not, slope = -2.25, t(162) = 1.11, p = .27. For women with no pre-college assault history, there was no interaction between negative urgency and college assault in predicting anxiety/depression symptoms. This unanticipated finding should be replicated before theoretical and clinical inferences are drawn. Last, we found no evidence of a three-way interaction among pre-college assault, college assault, and trait anxiety/depression in analyses for either hypothesis.

Figure 4.

Depiction of three-way interaction between negative urgency, freshman year sexual assault experience, and pre-college sexual assault history. The top panel depicts results for women positive for pre-college sexual assault history who were or were not assaulted freshman year. The bottom panel depicts results for women negative for pre-college sexual assault history who were or were not assaulted freshman year.

Discussion

The findings of this study provide clear support for the hypothesis that variations in premorbid personality interact with the experience of sexual assault to predict variations in the nature of post-assault experience. Specifically, the trait of negative urgency interacted with sexual assault to predict increases in one marker of externalizing behavior, which was drinking QF. Sexual assault has been shown to predict subsequent increases in substance use (Ullman et al., 2013). This effect was significantly stronger for women with elevated levels of negative urgency. Among women who are sexually assaulted, those high in negative urgency are most likely to increase their drinking behavior. This effect operated whether women were experiencing their first sexual assault or were re-victimized.

In contrast, trait anxiety/depression (the disposition to respond to events in anxious or depressive ways) interacted with sexual assault to predict increases in symptoms of clinical anxiety and depression, which is a marker of internalizing behavior. Sexual assault has been shown to predict subsequent increases in anxiety or depressive symptoms (Acierno et al., 2002; Clum et al., 2000). This effect was significantly stronger for women with elevations in trait anxiety/depression. As was true for the Negative Urgency × Sexual Assault interaction, this effect operated whether women were experiencing their first sexual assault or were re-victimized.

Together, these findings may help explain why some women experience increases in externalizing behaviors and others in internalizing behaviors following sexual assault. Pre-assault personality characteristics that are predictors of externalizing (negative urgency) or internalizing (trait anxiety/depression) dysfunction may help shape the form of women’s specific reactions to the trauma. We qualify this conclusion in two ways. First, given the many intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual factors that influence drinking behavior and anxiety/depressive symptoms, the impact of personality in shaping responses to sexual assault is modest. Second, an important future direction is to investigate whether and how internalizing and externalizing experiences transact to influence the risk process.

An unanticipated finding of potential interest was that high levels of trait anxiety/depression in women who reported previous assault interacted with sexual assault experience to predict lower levels of drinking. We highlight two related possible explanations for this finding. First, the predictive influence of trait anxiety/depression was above and beyond that of negative urgency; perhaps elevations in that part of trait anxiety/depression that is unrelated to negative urgency capture only that part of distress that is unassociated with risk taking or acting out. Related to this, perhaps women with such elevations were more likely to withdraw from social occasions and were thus less likely to be in situations where drinking is occurring.

We also observed an unanticipated three-way interaction, which suggested that the interaction between negative urgency and freshman year sexual assault actually predicts increases in symptoms of anxiety/depression for those women who were re-victimized. We consider it best to withhold speculation as to the meaning of this finding, pending its replication.

There are empirically supported interventions that reduce an individual’s risk for engaging in distress-driven rash action (Linehan, 1993) and their risk for engaging in substance abuse (Marlatt et al., 1998). There are other interventions most effective for internalizing expressions of distress (Chambless & Ollendick, 2001, Hayes et al., 1999). A clearer understanding of the differences between the two types of responses to trauma can facilitate the choice of effective treatment, and developing an empirically supported combination of personality-driven treatments with validated treatments aimed to reduce the risk of sexual assault re-victimization and alcohol use could improve treatment success (Angelo et al., 2008; Gilmore et al., 2015; Orchowski et al., 2008).

It is important to note the limitations of this study. One is the rate of retention, although missing participants did not vary from retained participants on study variables, and retention rates for longitudinal sexual assault studies tend to be lower than others (Campbell et al., 2011). Second, the longitudinal period of 1 academic year may not have been long enough to see more maladaptive outcomes develop. Third, we were unable to examine the effects of the characteristic of the assault experience. Fourth, all data were collected by self-report questionnaire using a web-based format; there was thus no opportunity to clarify questions or responses. However, confidential self-report is likely the most effective method for obtaining data of this sensitive nature because women may be more likely to under-report sexual assaults in person (Ongena & Dijkstra, 2007), and questionnaire data are often more reliable than interview data (Testa et al., 2005). Fifth, we were unable to examine the role of childhood sexual abuse history, which is surely important to this process (Classen et al., 2005). Finally, the sample is made up of predominantly White college women, which limits generalizability.

The finding that different pre-assault personality characteristics predict different patterns of post-assault distress is novel and important. It can contribute to etiological models of post-assault distress and lead to more effective, personspecific interventions for assaulted women.

Footnotes

This research is supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Grant RO1AA016166 (to Gregory T. Smith), NIAAA Grant 1F31AA020767-01A1 (to Jessica L. Combs), and National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant DA035200 (to Craig Rush).

References

- Acierno R., Brady K., Gray M., Kilpatrick D. G., Resnick H., Best C. L. Psychopathology following interpersonal violence: A comparison of risk factors in older and younger adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 2002;8:13–23. doi:10.1023/A:1013041907018. [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. D. Missing data techniques for structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:545–557. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo F. N., Miller H. E., Zoellner L. A., Feeny N. C. “I need to talk about it”: A qualitative analysis of trauma-exposed women’s reasons for treatment choice. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.02.002. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace & Company; 1990. Beck Anxiety Inventory manual. [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. T., Steer R. A., Brown G. K. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace & Company; 1996. BDI-II manual. [Google Scholar]

- Bedard-Gilligan M., Kaysen D., Desai S., Lee C. M. Alcohol-involved assault: Associations with posttrauma alcohol use, consequences, and expectancies. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:1076–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.001. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blayney J. A., Read J. P., Colder C. Role of alcohol in college sexual victimization and postassault adaptation. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2016;8:421–430. doi: 10.1037/tra0000100. doi:10.1037/tra0000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N. Epidemiologic studies of trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder, and other psychiatric disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;47:923–929. doi: 10.1177/070674370204701003. doi:10.1177/070674370204701003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R., Sprague H. B., Cottrill S., Sullivan C. M. Longitudinal research with sexual assault survivors: A methodological review. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:433–461. doi: 10.1177/0886260510363424. doi:10.1177/0886260510363424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless D. L., Ollendick T. H. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen C. C., Palesh O. G., Aggarwal R. Sexual revictimization: A review of the empirical literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2005;6:103–129. doi: 10.1177/1524838005275087. doi:10.1177/1524838005275087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum G. A., Calhoun K. S., Kimerling R. Associations among symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder and self-reported health in sexually assaulted women. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2000;188:671–678. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200010000-00005. doi:10.1097/00005053-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs J. L., Jordan C. E., Smith G. T. Individual differences in personality predict externalizing versus internalizing outcomes following sexual assault. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6:375–383. doi: 10.1037/a0032978. doi:10.1037/a0032978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa P. T., McCrae R. R. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. NEO PI-R. Professional manual. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders M. A., Smith G. T. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: Positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. doi:10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson C. K., Holmes M. M. Adolescent sexual assault: An update of the literature. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2004;16:383–388. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200410000-00005. doi:10.1097/00001703-200410000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. C., Gilmore A. K., Stappenbeck C. A., Balsan M. J., George W. H., Norris J. How to score the Sexual Experiences Survey? A comparison of nine methods. Psychology of Violence. 2014;4:445–461. doi: 10.1037/a0037494. doi:10.1037/a0037494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C. K., Peugh J. L. Using an EM covariance matrix to estimate structural equation models with missing data: Choosing an adjusted sample size to improve the accuracy of inferences. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:1–19. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM1101_1. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S., Peterson C. M., McCarthy D. A prospective test of the influence of negative urgency and expectancies on binge eating and purging. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:294–300. doi: 10.1037/a0029323. doi:10.1037/a0029323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier P., Anders S., Perera S., Tomich P., Tennen H., Park C., Tashiro T. Traumatic events among undergraduate students: Prevalence and associated symptoms. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:450–460. doi:10.1037/a0016412. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore A. K., Lewis M. A., George W. H. A randomized controlled trial targeting alcohol use and sexual assault risk among college women at high risk for victimization. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;74:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.007. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin M. J., Wardell J. D., Read J. P. Recent sexual victimization and drinking behavior in newly matriculated college students: A latent growth analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:966–973. doi: 10.1037/a0031831. doi:10.1037/a0031831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes S. C., Strosahl K. D., Wilson K. G. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J. M., Neale M. C., Myers J. M., Prescott C. A., Kendler K. S. A population-based twin study of the relationship between neuroticism and internalizing disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:857–864. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.857. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopko D. R., Lejuez C. W., Ruggiero K. J., Eifert G. H. Contemporary behavioral activation treatments for depression: Procedures, principles, and progress. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23:699–717. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00070-9. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick D. G., Ruggiero K. J., Acierno R., Saunders B. E., Resnick H. S., Best C. L. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss M. P., Abbey A., Campbell R., Cook S., Norris J., Testa M., White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Quarterly, Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x. [Google Scholar]

- Koss M. P., Gidycz C. A. Sexual Experiences Survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.422. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss M. P., Oros C. J. Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.3.455. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R. F., Markon K. E. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and classifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. M. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. Cognitive behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H., Ullman S. E. PTSD symptomatology and hazardous drinking as risk factors for sexual assault revictimization: Examination in European American and African American women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:345–353. doi: 10.1002/jts.21807. doi:10.1002/jts.21807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynam D. R., Smith G. T., Whiteside S. P., Cyders M. A. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University; 2006. The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior (Technical Report) [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G. A., Baer J. S., Kivlahan D. R., Dimeff L. A., Larimer M. E., Quigley L. A., Williams E. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year followup assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ongena Y. P., Dijkstra W. A model of cognitive processes and conversational principles in survey interview interaction. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 2007;21:145–163. doi:10.1002/acp.1334. [Google Scholar]

- Orchowski L. M., Gidycz C. A., Raffle H. Evaluation of a sexual assault risk reduction and self-defense program: A prospective analysis of a revised protocol. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32:204–218. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00425.x. [Google Scholar]

- Petrak J., Doyle A., Williams L., Buchan L., Forster G. The psychological impact of sexual assault: A study of female attenders of a sexual health psychology service. Sexual and Marital Therapy. 1997;12:339–345. doi:10.1080/02674659708408177. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher K. J., Curran P. J., Bauer D. J. Computational tools for probing interaction effects in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 2006;31:437–448. doi:10.3102/10769986031004437. [Google Scholar]

- Settles R. F., Cyders M., Smith G. T. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:198–208. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. doi:10.1037/a0017631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles R. E., Fischer S., Cyders M. A., Combs J. L., Gunn R. L., Smith G. T. Negative urgency: A personality predictor of externalizing behavior characterized by neuroticism, low conscientiousness, and disagreeableness. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:160–172. doi: 10.1037/a0024948. doi:10.1037/a0024948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., Cyders M. A. Integrating affect and impulsivity: The role of positive and negative urgency in substance use risk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;163(Supplement 1):S3–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. T., McCarthy D. M., Goldman M. S. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:383–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. doi:10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Livingston J. A., VanZile-Tamsen C. The impact of questionnaire administration mode on response rate and reporting of consensual and nonconsensual sexual behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2005;29:345–352. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00234.x. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman S. E., Najdowski C. J. Revictimization as a moderator of psychosocial risk factors for problem drinking in female sexual assault survivors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:41–49. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.41. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: Office of Civil Rights; 2011. Dear colleague letter: Sexual violence.https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-201104.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Walsh K., Resnick H. S., Danielson C. K., McCauley J. L., Saunders B. E., Kilpatrick D. G. Patterns of drug and alcohol use associated with lifetime sexual revictimization and current posttraumatic stress disorder among three national samples of adolescent, college, and household-residing women. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.006. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside S. P., Lynam D. R. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox P., Jordan C. E., Pritchard A. J. A multidimensional examination of campus safety: Victimization, perceptions of danger, worry about crime, and precautionary behavior among college women in the post-Clery era. Crime and Delinquency. 2007;53:219–254. doi:10.1177/0097700405283664. [Google Scholar]