Abstract

Objective:

As legalization of nonmedical retail marijuana increases, states are implementing public health campaigns designed to prevent increases in youth marijuana use. This study investigated which types of marijuana-related messages were rated most highly by parents and their teens and whether these preferences differed by age and marijuana use.

Method:

Nine marijuana-focused messages were developed as potential radio, newspaper, or television announcements. The messages fell into four categories: information about the law, general advice/conversation starters, consequences of marijuana use/positive alternatives, and information on potential harmful effects of teen marijuana use. The messages were presented through an online survey to 282 parent (84% female) and 283 teen (54% female) participants in an ongoing study in Washington State.

Results:

Both parents and youth rated messages containing information about the law higher than other types of messages. Messages about potential harms of marijuana use were rated lower than other messages by both generations. Parents who had used marijuana within the past year (n = 80) rated consequence/positive alternative messages lower than parent nonusers (n = 199). Youth marijuana users (n = 77) and nonusers (n = 202) both rated messages containing information about the law higher than other types of messages. Youth users and nonusers were less likely than parents to believe messages on the harmful effects of marijuana.

Conclusions:

The high ratings for messages based on information about the marijuana law highlight the need for informational health campaigns to be established as a first step in the marijuana legalization process.

In 2012, washington became one of the first states to legalize retail marijuana for adults, and, in the summer of 2014, retail outlets began selling marijuana across the state. Although sale to youth under age 21 remains illegal, legalization of retail sale might lead to greater exposure to and availability of marijuana for adolescents. The marijuana market may start to mirror that of other legal substances, where easy availability of alcohol and cigarettes for youth, from both commercial and social sources, is widespread (Everett Jones & Caraballo, 2014). Prevalence of marijuana use among adolescents has changed little during the past 15 years and still lags behind alcohol use. In 2016, 23.9% of 10th-grade and 35.6% of 12th-grade students reported using marijuana in the past year, compared with 38.3% and 55.6%, respectively, for alcohol (Johnston et al., 2017). As the legal marijuana market becomes established and prices begin to drop, it is possible that adolescent marijuana use could increase.

Parents have expressed confusion over how to communicate with their adolescent children about marijuana now that it is legal for adults (Kosterman et al., 2016; Mason et al., 2015; Roffman, 2012). Furthermore, both parents and teens have reported a lack of knowledge about the specifics of the law (Mason et al., 2015). When the sample used in the current study was asked three basic questions about the content of the marijuana law (legal age of use, legal amount of possession, whether homegrown marijuana is legal), about 60%–70% of parents and youth knew answers to individual questions, yet less than 30% answered all three questions correctly (Mason et al., 2015). Because parents’ behavior and attitudes about substance use and their communications with their adolescents on the topic predict use levels among their teens (Jackson & Dickinson, 2003; Kelly et al., 2002), parental knowledge of what is and is not legal may help them better communicate with their children in this changing environment (Jackson, 2002).

Public information campaigns have demonstrated some effectiveness in relation to law changes related to seatbelt use (Vasudevan et al., 2009), texting and driving (Kareklas & Muehling, 2014), and driving under the influence (Elder et al., 2004). Moreover, some research indicates that community-wide health communication campaigns can reduce youth marijuana use. Televised campaigns with high reach and frequency targeting high-risk adolescent populations have been shown to significantly reduce marijuana use (Palmgreen et al., 2001), and national campaigns such as “Above the Influence” have also shown potential (Slater et al., 2011). Yet, creating such campaigns in the age of retail marijuana legalization is uncharted territory. Colorado’s “Don’t Be a Lab Rat” campaign, which depicted human-sized laboratory cages containing information on the effects of marijuana on teen brain development, had mixed results. Some questioned the effectiveness of cages in helping youth understand the potential harms of marijuana; others argued that, regardless of any backlash, the campaign at least started a conversation about youth marijuana use in a legal environment (Frosch, 2014).

The somewhat negative reaction to the Colorado campaign demonstrates the need for further development and testing of marijuana messages that are positively received. Research tells us that messages must be perceived as relevant, trustworthy, credible, and persuasive in order to gain the attention of the target audience and, ultimately, have an impact (Lewis et al., 2016; Voltmer & Römmele, 2001). For this study, we applied those characteristics to the development and testing of messages about marijuana as retail stores began to open in Washington State.

Based on themes extracted from focus groups conducted with youth and parent participants in an experimental trial of a parenting intervention in urban Washington State (Skinner et al., 2017), we developed four styles of messages for parents and teens: informational messages about the law; messages containing general advice/conversation starters for parents; messages with a focus on consequences and offering positive alternatives for youth; and messages about potential harmful effects of youth marijuana use. The purpose of this study was to understand how each of these four types of messages was received by parents and their teens who were participating in the parenting intervention trial. We also investigated whether messages were perceived differently by users and nonusers of marijuana to see if certain message types resonate better within population subgroups.

Method

Message development

We conducted six focus groups in Tacoma, Washington, in 2013, about a year after the law legalizing adult use of marijuana was passed, but before retail outlets were open. The focus groups were semi-structured discussions on issues such as current names for marijuana, concerns about legalization, and what type of messaging might be effective in preventing youth marijuana use (see Skinner et al., 2017). Participants were not specifically asked to draw comparisons with other substances, although alcohol and tobacco communications were brought up by both parents and youth. Key themes were identified and included both parents and teens expressing an interest in more and better information about marijuana and the law, reliable information about the risks of marijuana use during adolescence, and real people’s stories about the consequences of use. Focus group participants also emphasized the need for trustworthy messengers. Discussions with teens focused on whether parents were trustworthy sources; parents felt that messages from doctors, schools, or churches could be effective, but that messages should not come from law enforcement or celebrities (Skinner et al., 2017). These themes formed the foundation of our message development.

In the winter of 2014, 18 people (6 project staff and 12 design students and faculty) attended a 4-hour design meeting to review the focus group findings and translate them into potential messages for parents and teens. This yielded message prototypes that were then provided to a design student who, along with input from researchers, turned the ideas into testable messages. Nine messages, falling into four general categories, were developed through this process. Two of these were radio messages that were developed by the Washington Traffic Safety Commission in collaboration with the study. Five messages were formatted as posters that could potentially be displayed on billboards or buses, and two messages were rough sketches of possible television or other visual media messages, displayed in a slideshow format. To recognize the request for trustworthy messengers, one radio message was recorded by a physician from Seattle Children’s Hospital. Although parents specifically noted that law enforcement may not be an effective source, one poster featured a member of the Washington State Patrol and was included because it provided information about the law and was already developed and in use by the Traffic Safety Commission.

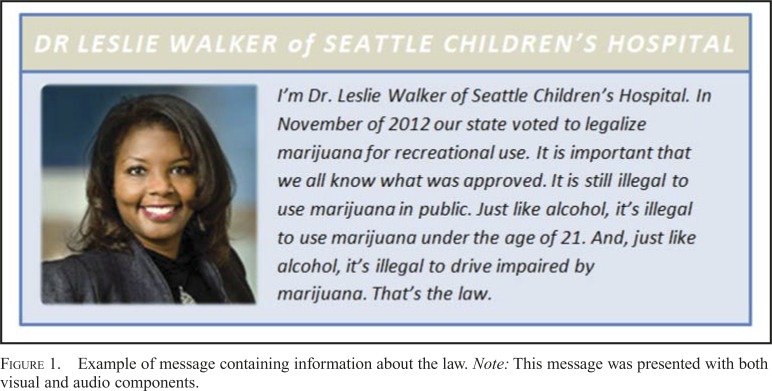

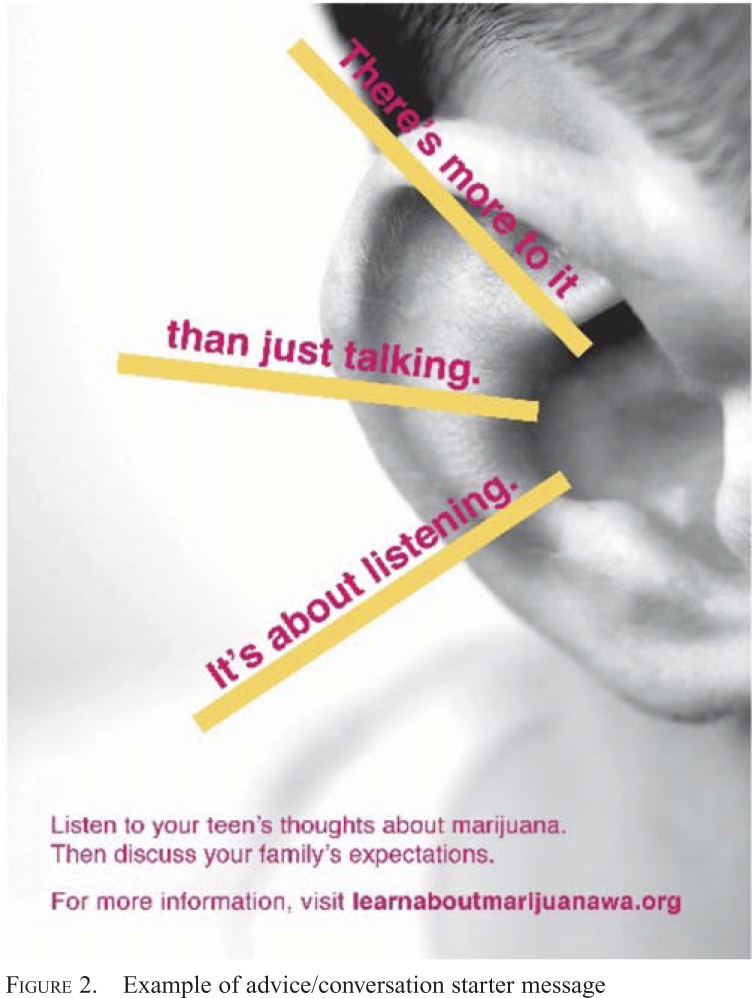

Messages were grouped according to the themes that emerged in the focus groups. Because our messages were presented in a variety of formats, grouping messages allowed us to investigate how well a particular theme versus a particular message resonated with our audience. One radio message and one poster provided information about the law such as legal age for marijuana use, rules regarding use in public, and reminders that it is illegal to drive while under the influence of marijuana. Another two messages, one radio and one poster, offered parents advice on having conversations with their children about marijuana, encouraging parents to initiate conversations and listen to their child’s opinions. One poster and two slideshows touched briefly on potential negative consequences of marijuana use (unemployment, school dropout, missed opportunities) while providing suggestions for positive alternative activities. These messages were designed to increase awareness of potential problems caused by marijuana use while providing nonconfrontational motivation to make positive choices. Two posters highlighted possible harmful physiological and psychological effects of youth marijuana use, such as addiction, lack of judgment, memory loss, and depression stemming from use during adolescence. See Figures 1 and 2 for example messages and Table 1 for a summary of message types and content.

Figure 1.

Example of message containing information about the law. Note: This message was presented with both visual and audio components.

Figure 2.

Example of advice/conversation starter message

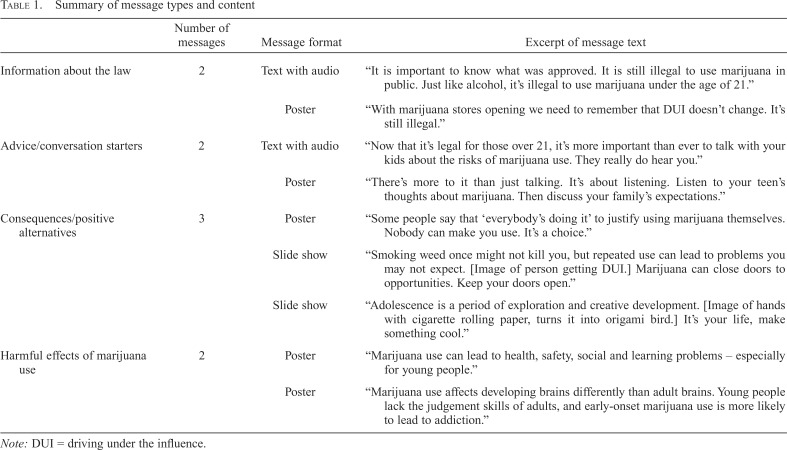

Table 1.

Summary of message types and content

| Number of messages | Message format | Excerpt of message text | |

| Information about the law | 2 | Text with audio | “It is important to know what was approved. It is still illegal to use marijuana in public. Just like alcohol, it’s illegal to use marijuana under the age of 21.” |

| Poster | “With marijuana stores opening we need to remember that DUI doesn’t change. It’s still illegal.” | ||

| Advice/conversation starters | 2 | Text with audio | “Now that it’s legal for those over 21, it’s more important than ever to talk with your kids about the risks of marijuana use. They really do hear you.” |

| Poster | “There’s more to it than just talking. It’s about listening. Listen to your teen’s thoughts about marijuana. Then discuss your family’s expectations.” | ||

| Consequences/positive alternatives | 3 | Poster | “Some people say that ‘everybody’s doing it’ to justify using marijuana themselves. Nobody can make you use. It’s a choice.” |

| Slide show | “Smoking weed once might not kill you, but repeated use can lead to problems you may not expect. [Image of person getting DUI.] Marijuana can close doors to opportunities. Keep your doors open.” | ||

| Slide show | “Adolescence is a period of exploration and creative development. [Image of hands with cigarette rolling paper, turns it into origami bird.] It’s your life, make something cool.” | ||

| Harmful effects of marijuana use | 2 | Poster | “Marijuana use can lead to health, safety, social and learning problems – especially for young people.” |

| Poster | “Marijuana use affects developing brains differently than adult brains. Young people lack the judgement skills of adults, and early-onset marijuana use is more likely to lead to addiction.” |

Note: DUI = driving under the influence.

Some of the messages were focused more toward parents, some more toward youth, and some were applicable to both generations. Messages on conversation starters were designed more for parents, whereas messages emphasizing positive choices spoke to a younger audience; information about the law and messages on potential harmful effects of marijuana use were relevant to all ages. Even though some messages were geared more toward particular age groups, all messages were presented to each respondent, as feedback from both youth and parents offered unique perspectives (e.g., Do youth feel that a particular message will encourage their parents to start a discussion about marijuana use?).

Study sample

The participants in this study were part of an ongoing longitudinal study in Tacoma, Washington, examining the effects of a parenting program, Common Sense Parenting® (Burke et al., 2006; Mason et al., 2016). Each family included a target parent and eighth-grade student who attended one of five middle schools at the time the study started. Two waves of families were enrolled in the initial study, the first during the 2010–2011 school year followed by the second a year later. Most students at the schools were from low-income families and were specifically selected for being at elevated risk for high school dropout. At the recruitment schools, just over 70% of the students received free or reduced-price school lunch in the 2010–2011 school year. All study procedures, including those for obtaining consent/assent, were approved by the human subjects review committees at the University of Washington, Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Home, and the participating school district. Participants were randomly assigned to the Common Sense Parenting condition (CSP, a parent training program currently in widespread use by Boys Town), CSP Plus Stepping up to High School (an adaptation of the standard curricula that includes adolescents in the workshops), or a control group. No intervention effects on either parent or teen attitudes or beliefs about substance use were evident in the larger study (Mason et al., 2016).

Three hundred and twenty-one families were enrolled in the original longitudinal project. The data for this study were collected in 2014 and include 283 youth and 282 parents recruited from both waves. The youth were 54% female, 32% White, 33% African American, 16% Hispanic/Spanish/Latino, and 19% other race/ethnicity. At the time of the survey, 66% of the youth were in 10th grade (the remainder in 11th grade), and the mean age was 17 years (range: 15–18). Parents/caregivers were 84% female, 39% White, 28% Black/African American, 13% Hispanic/Spanish/Latino, and 20% other race/ethnicity. The mean age of parents at the time of the survey was 43 years. Twenty-eight percent of youth and 29% of parents reported having used marijuana in the past year.

Measures

Study participants were invited to complete an online survey. The survey took about 20 minutes, and respondents were visually shown each message (audio recordings were included for two of the messages) followed by a series of questions asking them to rate each message on characteristics identified as salient for public service messages to be impactful (Pfleiderer, 2001; Schönbach, 2001). Respondents were also asked open-ended questions about what they liked and did not like about the message. After reviewing the messages and considering the pros and cons, participants were asked to provide an overall summary rating for each message (“Overall, how would you rate this message?”) on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 9 (very good). Messages were grouped by the four message categories (information about the law, advice/conversation starters, consequences/positive alternatives, and potential harmful effects), and the mean score on the overall rating scale was calculated for each message type. Given the importance of persuasive appeal in health-related messages, this initial study focused on evaluating overall ratings of messages.

Analysis

We assessed differences in overall ratings between message types within groups using matched-pairs t tests. Independent sample t tests were used to compare mean scores reported by different groups (i.e., parents and youth or marijuana users and nonusers). Standardized differences (d) were calculated by dividing differences by the average standard deviation of ratings for message types or for different groups’ ratings.

The open-ended responses were initially coded into general themes by a group of three researchers (a single response could be coded into multiple categories). One individual reviewed the themes and generated a final list of broader themes into which the categories were collapsed. The percentage of respondents whose comments were coded into each theme was calculated for each message type, and these percentages were ranked to determine the most common themes.

Results

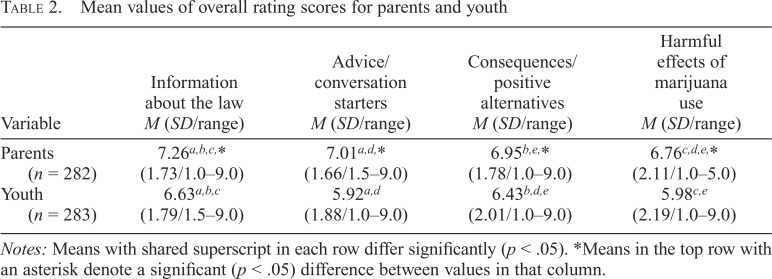

Table 2 provides mean scores of the overall ratings of the messages by type for parents and youth. Although all the messages were rated highly (average scores ranged from 6.76 to 7.26 on a scale of 1–9), parents rated messages more favorably than youth for all four message types (ds = 0.27–0.62). There were no differences by gender in message ratings for either parents or youth. Both parents and youth rated messages containing information about the law higher than messages containing advice/conversation starters, messages focusing on consequences/positive alternatives, and messages about potential harmful effects of teen marijuana use (ds = 0.11–0.39).

Table 2.

Mean values of overall rating scores for parents and youth

| Variable | Information about the law (SD/range) | Advice/conversation starters (SD/range) | Consequences/positive alternatives (SD/range) | Harmful effects of marijuana use (SD/range) |

| Parents (n = 282) | 7.26a,b,c,* (1.73/1.0–9.0) | 7.01a,d,* (1.66/1.5–9.0) | 6.95b,e,* (1.78/1.0–9.0) | 6.76c,d,e,* (2.11/1.0–5.0) |

| Youth (n = 283) | 6.63a,b,c (1.79/1.5–9.0) | 5.92a,d (1.88/1.0–9.0) | 6.43b,d,e (2.01/1.0–9.0) | 5.98c,e (2.19/1.0–9.0) |

Notes: Means with shared superscript in each row differ significantly (p < .05).

Means in the top row with an asterisk denote a significant (p < .05) difference between values in that column.

Not surprisingly, youth rated messages about advice/conversation starters lower than other types (e.g., d = 0.39 compared with ratings for messages containing information about the law), as those messages were geared toward parents. Even though messages about the potential harmful effects of marijuana focused on risks of use during adolescence, both parents and youth rated these messages lower than almost all other types. Parents rated messages about the harms of marijuana use lower than all other message types (ds = 0.10–0.26), whereas youth rated them significantly lower than messages about the law (d = 0.33) and those aimed toward consequences/positive alternatives (d = 0.21).

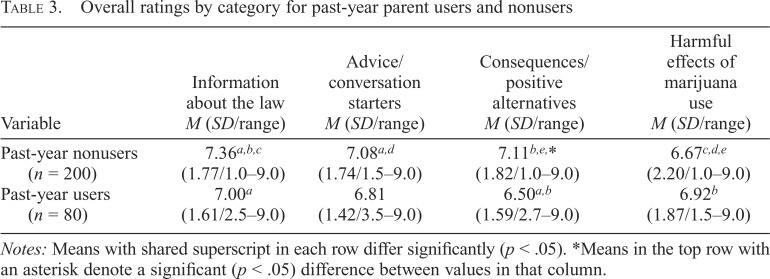

Because people who use marijuana may have different attitudes toward marijuana messaging than those who do not use, we investigated if there were differences in message ratings based on whether respondents reported marijuana use at least once in the past year. Similar to the overall responses, parent nonusers rated messages containing information about the law higher than all other messages; they rated messages on potential harmful effects of marijuana lowest. Among parent users, only the difference between informational messages versus consequences/positive alternatives (d = 0.31) and harmful effects of marijuana versus consequences/positive alternatives (d = 0.24) were statistically significant (Table 3). Comparing parent users and nonusers, parents who reported using marijuana in the past year rated messages about consequences and positive alternatives lower than parents who said they had not used marijuana in the past year (d = 0.36).

Table 3.

Overall ratings by category for past-year parent users and nonusers

| Variable | Information about the law M (SD/range) | Advice/conversation Starters M (SD/range) | Consequences/Positive alternatives M (SD/range) | Harmful effects of marijuana use M (SD/range) |

| Past-year nonusers (n = 200) | 7.36a,b,c (1.77/1.0–9.0) | 7.08a,d (1.74/1.5–9.0) | 7.11b,e,* (1.82/1.0–9.0) | 6.67c,d,e (2.20/1.0–9.0) |

| Past-year users (n = 80) | 7.00a (1.61/2.5–9.0) | 6.81 (1.42/3.5–9.0) | 6.50a,b (1.59/2.7–9.0) | 6.92b (1.87/1.5–9.0) |

Notes: Means with shared superscript in each row differ significantly (p < .05).

Means in the top row with an asterisk denote a significant (p < .05) difference between values in that column.

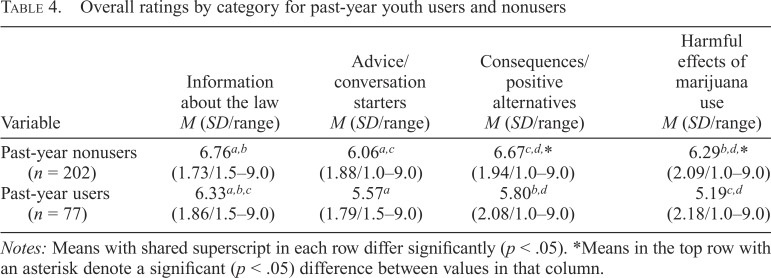

For youth, messages about what is contained in the law were again rated highly by youth who reported using marijuana in the past year and those who did not (Table 4). Both youth groups also rated messages about consequences/positive alternatives higher than those containing information on potential harmful effects of marijuana use (d = 0.19 and d = 0.29, respectively). Comparing youth users and nonusers, nonusers rated messages about consequences/positive alternatives and potential harmful effects of marijuana higher than users (d = 0.43 and d = 0.52, respectively).

Table 4.

Overall ratings by category for past-year youth users and nonusers

| Variable | Information about the law M (SD/range) | Advice/conversation Starters M (SD/range) | Consequences/positive Alternatives M (SD/range) | Harmful effects of marijuana use M (SD/range) |

| Past-year nonusers (n = 202) | 6.76a,b (1.73/1.5–9.0) | 6.06a,c (1.88/1.0–9.0) | 6.67c,d,* (1.94/1.0–9.0) | 6.29b,d,* (2.09/1.0–9.0) |

| Past-year users (n = 77) | 6.33a,b,c (1.86/1.5–9.0) | 5.57a (1.79/1.5–9.0) | 5.80b,d (2.08/1.0–9.0) | 5.19c,d (2.18/1.0–9.0) |

Notes: Means with shared superscript in each row differ significantly (p < .05).

Means in the top row with an asterisk denote a significant (p < .05) difference between values in that column.

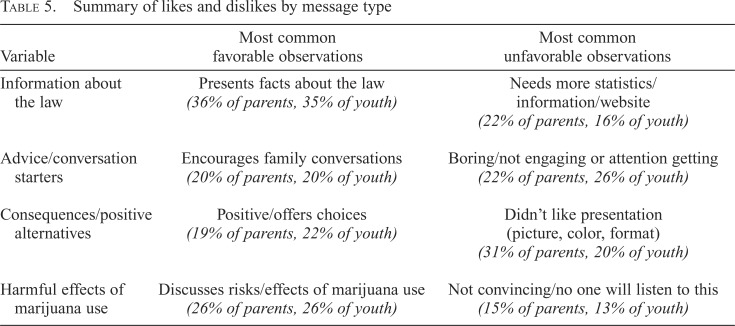

The open-ended responses allowed us to further investigate what respondents liked and did not like about the four message types. For messages containing information about the law, the most common theme, reported by 36% of parents and 35% of youth, was appreciation that the messages provided information about the law (Table 5). For example, they wrote, “I like the fact that it gives more information about the law. I was unsure about the factors of this law (age limit, where it can be used, etc.)”; and “I had no idea it was illegal to drive after smoking. I thought DUI [driving under the influence] was only for drinking and driving.” Although respondents approved of the information provided, a request by 22% of parents and 16% of youth was for these messages to contain even more information or the addition of a website as a further resource. For example: “It doesn’t share how you would know if you were driving impaired under marijuana. What is the test/limits/quantity to prove if you are impaired or not?” and “There is nothing showing where more information can be found.” Messages containing advice were thought to encourage family conversations (“It gives me a reminder to talk to my kids about it, also opens the doors to discussion if we see the ad together.”) but were considered somewhat bland (“Kids these days like to read what catches their eye; I would’ve never read this.”).

Table 5.

Summary of likes and dislikes by message type

| Variable | Most common favorable observations | Most common unfavorable observations |

| Information about the law | Presents facts about the law (36% of parents, 35% of youth) | Needs more statistics/information/website (22% of parents, 16% of youth) |

| Advice/conversation starters | Encourages family conversations (20% of parents, 20% of youth) | Boring/not engaging or attention getting (22% of parents, 26% of youth) |

| Consequences/positive alternatives | Positive/offers choices (19% of parents, 22% of youth) | Didn’t like presentation (picture, color, format) (31% of parents, 20% of youth) |

| Harmful effects of marijuana use | Discusses risks/effects of marijuana use (26% of parents, 26% of youth) | Not convincing/no one will listen to this (15% of parents, 13% of youth) |

Messages about consequences and positive alternatives provided a creative spin and offered choices (“I like that it focused on positive things and teens versus the bad things that can happen.”). Our rudimentary slideshow format, however, was met with criticism: “While the message is right, the cartoons were childish and kind of corny for a teenager to take it seriously.” Both parents and youth liked that our messages discussed potential harmful effects of teen marijuana use, but some respondents felt that these messages were not convincing enough: “People know the risks but continue to do it. Telling them what happens is just another thing they don’t care about.”

Despite the lower ratings of messages about the harmful effects of marijuana, both parents (26%) and youth (26%) commented that they appreciated the messages that discussed possible risks and harms from marijuana use. However, they differed in how much they believed the information about these risks. Twenty percent of youth wrote something to the effect that they did not believe the information presented about the effects of marijuana or that they thought the message was negative toward marijuana use, compared with only 7% of parents. For example, youth wrote, “Other research shows there is no evidence on memory loss and it helps people cope with anxiety and actually opens up imagination in an individual’s brain”; “I know plenty of kids who smoke weed and get into college and get good grades”; “It instantly assumes and tries to convince people that marijuana is a harmful and negative substance”; and “I don’t see any real risk of marijuana. It has more than 150 uses including paper or even medicine.” This distrust was consistent across youth marijuana users and nonusers; 47% of the comments along this theme were made by youth who reported not using marijuana in the past year.

Discussion

Our analyses show a general preference for messages based on information about the marijuana law. Messages containing details of the law such as legal age, public use, and driving under the influence were consistently rated higher than all other message types. Review of the open-ended comments revealed that study participants did not have a strong understanding of the contents of the marijuana law even though the marijuana initiative was approved in Washington State 2 years before our study. These results not only are consistent with research showing that knowledge levels about basic aspects of the law are relatively low (Mason et al., 2015) but also highlight the need for educational media campaigns to be established early in the marijuana legalization process.

Current public health campaigns for alcohol and tobacco focus mainly on behavior and/or attitude change, drawing on a history of research into the perceived effectiveness of tobacco-related media messages (Davis et al., 2013; Niederdeppe et al., 2011; Wong & Cappella, 2009). These campaigns, however, are aided by a general understanding of laws surrounding alcohol and tobacco use, leaving them to focus on other outcomes. Many laws regarding legalized marijuana are still in development, differing across and even within states, and a general understanding of these laws appears to be lacking. Although informational messages may be most effective when combined with other strategies (National Cancer Institute, 2008; Robinson et al., 2014), our study emphasizes the need for states legalizing marijuana to initially develop public health campaigns designed to increase knowledge and awareness of the basic facts of the law.

Our results also showed that ratings of messages differed based on use and nonuse of marijuana. Although parents reporting use in the past year still ranked messages containing information about the law highly, the ratings were not as high as among parent nonusers and both youth users and nonusers. This possibly reflects a greater knowledge of the law among parents who have used marijuana and may have a greater interest in tracking changes in the laws. Both parent and youth users of marijuana rated messages about consequences/positive alternatives lower than their nonuser counterparts, which is consistent with research on tobacco campaigns showing minimal impact of negative consequence advertising on casual users (Goldman & Glantz, 1998). These differences in message ratings indicate that targeting messages toward specific groups may be more effective than a “one-size-fits-all” approach. Research on targeted versus general messages is still evolving, especially with new technologies allowing for greater customization of messages across an array of media. However, using data-driven messages aimed toward particular groups has been shown to be effective in general health communications (Kreuter et al., 2003).

Although parents and youth both rated messages containing information on the potential harm of marijuana use lower than other types of messages, skepticism about marijuana risks was more pronounced by youth in the open-ended responses. These insights are consistent with research using the Washington State Healthy Youth Survey, which shows a significant decrease in Washington State 10th graders’ perceived harm of marijuana from 2000 to 2014, combined with a significant increase in favorable attitudes toward marijuana over the same period (Washington State Healthy Youth Survey, 2015). Although research on the link between early marijuana use and a range of behavioral and physiological problems is well established (Hall, 2015; Volkow et al., 2014), these data are often countered by messages about the benefits of marijuana, particularly in the age of social media and marijuana legalization (Roditis et al., 2016). Youth perceive marijuana as less risky and more socially acceptable than cigarettes, and these changing attitudes toward marijuana among youth may require rethinking how best to reach youth with public health campaigns on the risks of marijuana.

This study has notable limitations. First, our sample was part of an existing study and was not recruited specifically to test marijuana messaging. A larger sample more representative of families across Washington State would have been preferable. Second, the messages, developed by a design student and researchers based on information from focus groups, were unpolished. This may have diminished their overall effectiveness. Likewise, given the exploratory, firststep nature of this study, it was not designed to disentangle the formatting, ordering, or platform of the messages from the content. Further, some messages, such as those emphasizing negative consequences of marijuana use alongside suggestions for positive alternatives, included multiple components, and we were only able to get ratings of the combination of these components. This study takes an important first step in examining parents’ and teens’ overall ratings of messages, rather than attempting to assess efficacy with respect to influencing behavior. Of course, messages that are positively rated may not have the desired impact. Future research is needed to test whether the messages developed here actually prevent adolescent marijuana use.

Conclusions

Providing clear information to parents and teens about changes to the law emerged as an important issue from the testing of messages. With more states legalizing medical and nonmedical marijuana in November 2016, marijuana use and its negative consequences could increase. States with legalization should recognize the need for information campaigns specific to their state to ensure that their residents are provided with clear, basic information about these new laws. Public health campaigns that disseminate details about marijuana laws should be included in state budgets and roll out before the opening of retail stores. In addition, targeting of messages toward users and nonusers of marijuana might be an effective means of reaching subpopulations, and states wanting to disseminate messages on potential harms of marijuana should account for youth skepticism and consider thorough testing of messages to evaluate their effectiveness. Although it remains to be seen what, if any, impact retail marijuana might have on youth substance use, states that have legalized marijuana and those considering legalization should be proactive in developing public information campaigns designed to increase knowledge and understanding of the law as a first step in the marijuana legalization process.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rebecca Cortes and Tiffany Jones for deftly facilitating the focus groups.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant 1R01DA025651. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agency.

References

- Burke R. V., Schuchmann L. F., Barnes B. A. 3rd ed. Boys Town, NE: Boys Town Press; 2006. Common Sense Parenting: Trainer guide. [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. C., Nonnemaker J., Duke J., Farrelly M. C. Perceived effectiveness of cessation advertisements: The importance of audience reactions and practical implications for media campaign planning. Health Communication. 2013;28:461–472. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.696535. doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.696535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder R. W., Shults R. A., Sleet D. A., Nichols J. L., Thompson R. S., Rajab W. the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Effectiveness of mass media campaigns for reducing drinking and driving and alcohol-involved crashes: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.002. doi:10.1016/jamepre.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everett Jones S., Caraballo R. S. Usual source of cigarettes and alcohol among US high school students. Journal of School Health. 2014;84:493–501. doi: 10.1111/josh.12174. doi:10.1111/josh.12174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch D. Colorado ‘Lab Rat’ campaign warns teens of pot use. The Wall Street Journal. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/lab-rat-ads-warn-teens-of-pot-use-1412560470. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman L. K., Glantz S. A. Evaluation of antismoking advertising campaigns. JAMA. 1998;279:772–777. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.10.772. doi:10.1001/jama.279.10.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W. What has research over the past two decades revealed about the adverse health effects of recreational cannabis use? Addiction. 2015;110:19–35. doi: 10.1111/add.12703. doi:10.1111/add.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. Perceived legitimacy of parental authority and tobacco and alcohol use during early adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:425–432. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00398-1. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00398-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C., Dickinson D. Can parents who smoke socialise their children against smoking? Results from the Smoke-free Kids intervention trial. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:52–59. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.1.52. doi:10.1136/tc.12.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Miech R. A., Bachman J. G., Schulenberg J. E. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2017. Monitoring the Future national results on drug use, 1975–2016: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. [Google Scholar]

- Kareklas I., Muehling D. D. Addressing the texting and driving epidemic: Mortality salience priming effects on attitudes and behavioral intentions. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 2014;48:223–250. doi:10.1111/joca.12039. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly K. J., Comello M. L., Hunn L. C. Parent-child communication, perceived sanctions against drug use, and youth drug involvement. Adolescence. 2002;37:775–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R., Bailey J. A., Guttmannova K., Jones T. M., Eisenberg N., Hill K. G., Hawkins J. D. Marijuana legalization and parents’ attitudes, use, and parenting in Washington State. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.004. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter M. W., Lukwago S. N., Bucholtz R. D., Clark E. M., Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: Targeted and tailored approaches. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30:133–146. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251021. doi:10.1177/1090198102251021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis I., Watson B., White K. M. The Step approach to Message Design and Testing (SatMDT): A conceptual framework to guide the development and evaluation of persuasive health messages. Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2016;97:309–314. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2015.07.019. doi:10.1016/j.aap.2015.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W. A., Fleming C. B., Gross T. J., Thompson R. W., Parra G. R., Haggerty K. P., Snyder J. J. Randomized trial of parent training to prevent adolescent problem behaviors during the high school transition. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016;30:944–954. doi: 10.1037/fam0000204. doi:10.1037/fam0000204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason W. A., Hanson K., Fleming C. B., Ringle J. L., Haggerty K. P. Washington State recreational marijuana legalization: Parent and adolescent perceptions, knowledge, and discussions in a sample of low-income families. Substance Use & Misuse. 2015;50:541–545. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.952447. doi:10.31 09/10826084.2014.952447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Tobacco Control Monograph No. 19. 2008 (NIH Pub. No. 07–6242). Bethesda, MD: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Niederdeppe J., Farrelly M. C., Nonnemaker J., Davis K. C., Wagner L. Socioeconomic variation in recall and perceived effectiveness of campaign advertisements to promote smoking cessation. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;72:773–780. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.025. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmgreen P., Donohew L., Lorch E. P., Hoyle R. H., Stephenson M. T. Television campaigns and adolescent marijuana use: Tests of sensation seeking targeting. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:292–296. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.292. doi:10.2105/AJPH.91.2.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfleiderer R. Using market research techniques to determine campaign effects. In: Klingemann H-D, Römmele A., editors. Public information campaigns and opinion research: A handbook for the student and practitioner. London, England: Sage; 2001. pp. 167–184. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson M. N., Tansil K. A., Elder R. W., Soler R. E., Labre M. P., Mercer S. L., Rimer B. K. Mass media health communication campaigns combined with health-related product distribution: A community guide systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47, 360–371. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.034. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roditis M. L., Delucchi K., Chang A., Halpern-Felsher B. Perceptions of social norms and exposure to pro-marijuana messages are associated with adolescent marijuana use. Preventive Medicine. 2016;93:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.013. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffman R.2012Op-ed: What parents should say to teens about I-502 and marijuana legalization [Editorial] The Seattle Times. Retrieved from http://seattletimes.com/html/opinion/2019648432_rogerroffmanopedxml.html [Google Scholar]

- Schönbach K. Using survey research to determine the effects of a campaign. In: Klingemann H-D, Römmele A., editors. Public information campaigns and opinion research: A handbook for the student and practitioner. London, England: Sage; 2001. pp. 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner M. L., Haggerty K. P., Casey-Goldstein M., Thompson R. W., Buddenberg L., Mason W. A. Focus groups of parents and teens help develop messages to prevent early marijuana use in the context of legal retail sales. Substance Use & Misuse. 2017;52:351–358. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1227847. doi:10.1080/10826084.2016.1227847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater M. D., Kelly K. J., Lawrence F. R., Stanley L. R., Comello M. L. G. Assessing media campaigns linking marijuana non-use with autonomy and aspirations: Be Under Your Own Influence and ONDCPs Above the Influence. Prevention Science. 2011;12:12–22. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0194-1. doi:10.1007/s11121-010-0194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan V., Nambisan S. S., Singh A. K., Pearl T. Effectiveness of media and enforcement campaigns in increasing seat belt usage rates in a state with a secondary seat belt law. Traffic Injury Prevention. 2009;10:330–339. doi: 10.1080/15389580902995190. doi:10.1080/15389580902995190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N. D., Baler R. D., Compton W. M., Weiss S. R. Adverse health effects of marijuana use, Adverse health effects of marijuana use. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370:2219–2227. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voltmer K., Römmele A. Information and communication campaigns: Linking theory to practice. In: Klingemann H-D, Römmele A., editors. Public information campaigns and opinion research: A handbook for the student and practitioner. London, England: Sage; 2001. pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Health Youth Survey. Healthy Youth Survey fact sheets. 2015 Retrieved from https://www.askhys.net/FactSheets.

- Wong N. C. H., Cappella J. N. Antismoking threat and efficacy appeals: Effects on smoking cessation intentions for smokers with low and high readiness to quit. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2009;37:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00909880802593928. doi:10.1080/00909880802593928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]