Abstract

The mechanism of cisplatin resistance is complex. Previous studies have indicated that chloride voltage-gated channel 3 (CLCN3) is associated with drug resistance; however, the mechanisms are not fully understood. Therefore, the present study explored the involvement of CLCN3 in cisplatin resistance in human glioma U251 cells. The effects of combined cisplatin treatment and CLCN3 suppression on cultured U251 cells were investigated. The decreased viability of cisplatin-treated U251 cells indicated the cytotoxic effects of CLCN3 silencing. Expression of the apoptosis-related gene TP53 and caspase 3 activation were enhanced in cisplatin-treated U251 cells. Furthermore, the ratio of BCL2/BAX expression was decreased. Notably, CLCN3 suppression promoted cisplatin-induced cell damage in U251 cells. Thus, the combined use of cisplatin and CLCN3 antisense had additive effects in U251 cells. In addition, the present results indicated that CLCN3 suppression decreased lysosome stabilization in U251 cells treated with cisplatin. To conclude, the present results indicated that CLCN3 suppression can sensitize glioma cells to cisplatin through lysosomal dysfunction.

Keywords: cisplatin, drug resistance, lysosome, chloride voltage-gated channel 3, glioma

Introduction

Gliomas arise from astrocytes, oligodendrocytes or their progenitor cells. The malignant transformation of all these cells are collectively called gliomas. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is the most common and invasive primary central nervous system tumor in adults, with a 2-year survival rate of 3–5%. Currently, the standard treatment for GBM is multimodal comprehensive treatment including surgery combined with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Surgically eliminating GBM is impossible, and GBMs are resistant to a variety of chemotherapy drugs including Temozolomide. Thus, tumor relapses are unavoidable, making the medial survival of GBM patients only 12 to 15 months (1).

The chloride transporter family is widely expressed in tissues and organs across the entire body (2). One member of the chloride voltage-gated channel (CLCN) family, CLCN3, is predominantly expressed in acidic intracellular compartments, especially lysosomes (3). CLCN3 participates in vesicular acidification, chloride accumulation, and drug resistance (4–7). Recent studies have shown that CLCN3 is highly expressed in GBM and plays significant roles in cellular survival, proliferation and malignancy (8,9).

Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum) is a DNA damaging agent that is widely used to treat a variety of malignant tumors, including gliomas (10,11). Fluorescence tagging assays indicate that cisplatin is taken up by cells, and then combines with membrane proteins, accumulating in endosomes, lysosomes and the Golgi through endocytic recycling compartments (12,13). Recent studies also indicated that cell internalization, membrane recycling, organelle acidification, and cell externalization are involved in the metabolism of cisplatin (13–15). However, the mechanism of resistance to cisplatin is complex and still not fully understood.

In this study, we utilized the human glioma cell line U251, which is relatively insensitive to cisplatin, to determine whether suppressing CLCN3 enhances the sensitivity of glioma cells to cisplatin. We investigated the effects of combined cisplatin and CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide treatment on U251 cells and compared the results with cells treated with cisplatin alone. Cytotoxicity, apoptosis induction, cell invasion and the expression of relative genes were assayed. We further elucidated the possible mechanisms involved in the different susceptibilities of U251 cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis. The results indicated that inhibiting CLCN3 increased the sensitivity of U251 cells to cisplatin through lysosomal dysfunction. These data provide new evidence that intracellular CLCN proteins could be a target to modulate chemosensitivity.

Materials and methods

Cell line and culture

All experiments were performed in U251 cells, which were maintained at 37°C with 95% air and 5% CO2, and in DMEM (HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences), 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Antisense and nonsense oligonucleotide transfection

Phosphorothioate-modified antisense oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Dalian, China). The CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide primer sequence used was: 5′-TCCATTTGTCATTGT-3′. The CLCN3 antisense was shown to eliminate both the short and long forms of CLCN3 (16). A nonsense primer sequence was constructed from 15 randomized bases (5′-CCGTATGACCGCGCC-3′) and served as an experimental control (17). Oligonucleotide primers were transfected into U251 cells using Lipofectamine® 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) according to manufacturer's instructions. The final concentration of oligonucleotide primers was 0.5–2 µg/ml. For reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) and western blotting, 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with cisplatin (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) for 24 h, and then were harvested.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from U251 cells using TRIzol (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used to reverse transcribe 2 µg RNA into cDNA. The PCR primers for matrix metalloprotease 2 (MMP2) (Genebank NM 004530.2) and MMP9 (Genebank NM 004994.2) were created with Primer 5 software (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, USA); CLCN3, CCND1 and ACTB primers have been published previously (18). The primers were synthesized by Takara. Primers sequences and related parameters are presented in Table I. PCR results were visualized using a Tanon-1600 figure gel image processing system and analyzed with GIS 1D gel image system software (Tanon, Shanghai, China).

Table I.

Primer sequences and related parameters.

| Gene | Sequence | Annealing temperature | Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| CLCN3 | Sense: 5′-CCTCTTTCCAAAGTATAGCAC-3′ | 55°C | 552 bp |

| Antisense: 5′-TTACTGGCATTCATGTCATTTC-3′ | |||

| MMP-2 | Sense: 5′-GTGCTGAAGGACACACTAAAGAAGA-3′ | 55°C | 605 bp |

| Antisense: 5′-GGATGTTGAAACTCTTCCTACCGTT-3′ | |||

| MMP-9 | Sense: 5′-CACTGTCCACCCCTCAGAGC-3′ | 57°C | 243 bp |

| Antisense: 5′-GGAATAGCGGCTGTTCACCG-3′ | |||

| β-actin | Sense: 5′-GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA-3′ | 55°C | 538 bp |

| Antisense: 5′-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3′ |

CLCN3, chloride voltage-gated channel 3; MMP, matrix metalloprotease.

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) that included a protease inhibitor cocktail (19) (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Protein quantification was performed using the Bio-Rad Protein assay dye reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were electrophoresed and separated by SDS-PAGE, and then transferred from gels onto PVDF membranes (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). After incubation with primary (4°C, overnight) and secondary antibodies (room temperature, 2 h), the blots were developed with DAB (3,3′-diaminobenzidine). Western blots results were analyzed with GIS 1D gel image system software. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-CLCN3 (1:100, sc-17572), anti-Bcl-2 (1:200, sc-783), anti-Bax (1:200, sc-7480), anti-pro-caspase 3 (1:200, sc-7148), anti-cleaved-caspase 3 (1:200, sc-22171), anti-cathepsin D (1:200, sc-136282), anti-β-actin (1:400, sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA). Secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Densitometry was used to calculate the ratio of CLCN3 to β-actin, cleaved caspase 3 to pro-caspase 3, and BCL2 to BAX signal in each lane.

MTT Assay

Cell viability was detected by the MTT assay. MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. Cells were grown in 96-well plates (1×104 cells/ml and 100 µl/well) maintained at 37°C with 95% air and 5% CO2 for 22–24 h. After oligonucleotide transfection and cisplatin treatment, 20 µl of MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well for 4 h. After removing the medium, 100 µl of DMSO was added to each well, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured with a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Morphological determination of apoptosis by TUNEL

Apoptotic morphological changes in cells were detected using a TUNEL assay according to the protocol of the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). Cells were fixed in 4% formaldehyde (4°C, 20 min), and incubated by TUNEL reagent (keep in dark, 37°C, 60 min). Glycerol was used as mounting medium. The results were observed using an Olympus fluorescence microscope (BX60; Olympus Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with 450–500 nm excitation wavelength and 515–565 nm (20) emission wavelength. Six fields of view observed under microscope.

Quantification of apoptosis by flow cytometry

Treated cells were collected and incubated with propidium iodide (PI) and Annexin V (both from Keygene, Nanjing, China), and then assayed using a fluorescence activated cell sorting system (FACS). Early apoptotic cells were only labelled with Annexin V (21). Samples were stained using the manufacturer's protocol and analyzed using a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The software used for flow cytometry analysis is BD CellQuest™ Pro (The Premier Acquisition and Analysis Software; Apple Computer, Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA).

Measuring Cathepsin D activity

Treated cells were collected and Cathepsin D activity was detected using the protocol supplied with the Cathepsin D activity assay kit (BioVision, Inc., Milpitas, CA, USA). Briefly, 1×106 cells were harvested, washed with ice cold PBS, resuspended in 100 µl of PBS, and centrifuged for 2–5 min at 4°C at full speed using a cold microcentrifuge to remove insoluble material. The cells were then resuspended in 200 µl of Cell Lysis Buffer, incubated on ice for 10 min and centrifuged for 2–5 min at 4°C at full speed using a cold microcentrifuge to remove insoluble material. The cleared cell lysate was then transferred into a new tube. We then added 52 µl of the Reaction Mix to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1–2 h in the dark. Fluorescence was detected using a Packard Bioscience Fusion™ instrument (Packard BioScience Co., Arvada, CO, USA) with a 328 nm excitation wavelength and a 460 nm emission wavelength.

Measuring intracellular acridine orange (AO) emission spectra

Our previous study found that AO accumulates in acidic compartments such as lysosomes, where it fluoresces red (22,23). After transfection and treatment, cells were incubated with AO (final concentration 5 µM). The granular red (lysosomal) fluorescence was measured using laser confocal micro-spectrofluorometry (FluoView™ FV300; Olympus Inc.).

Transwell invasion and mobility assay

Chambers with 8 µm pore filters (Becton Dickinson) were placed into a 24-well plate. Treated cells were harvested, resuspended, and then added to the upper compartment of the chamber (5×104 cells/200 µl). Matrigel-coated filters were used to detect cell invasion. Cells that invaded through the Matrigel were counted on the underside of the filter according to the manufacturer's instructions. The filter membranes with cells were stained by 0.1% crystal violet at room temperature for 10 min, and observed by optical microscope. Three independent experiments were performed.

Statistical analysis

All results are presented as mean ± standard error. The number of independent experiments are shown as n values. One-way ANOVA was used for all statistical analyses followed by Tukey's test. All data are carried out using the Student's t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

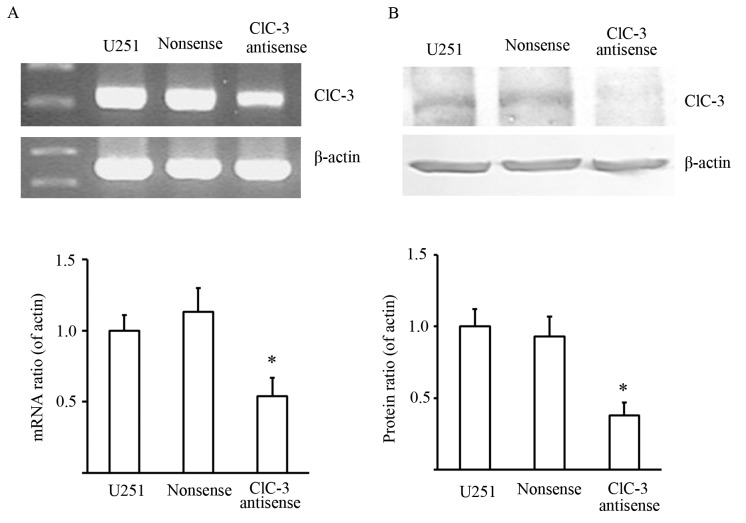

Effects of nonsense oligonucleotide and CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide transfection on CLCN3 mRNA and protein expression in U251 cells

Initially, we tested whether CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotides could effectively suppress CLCN3 mRNA and protein expression. RT-qPCR and western blot assays were performed to detect the effects of transfecting nonsense and CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide on CLCN3 mRNA and protein expression in U251 cells. The results showed that CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotides significantly decreased CLCN3 mRNA and protein expression. This indicated that CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotides could effectively suppress CLCN3 expression (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of nonsense and CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide transfection on CLCN3 mRNA and protein expression in U251 cells. (A) Densitometric analysis showing a significant decrease in CLCN3 mRNA expression induced by CLCN3 antisense transfection, whereas the transfection of a nonsense oligonucleotide did not significantly alter CLCN3 mRNA expression. (B) Representative RT-qPCR results are shown. β-actin was used as a loading control. The top panel shows the RT-qPCR and western blotting data for CLCN3 and β-actin from U251 cell lysates. The bottom panels show the integrated density values of CLCN3 relative to β-actin (n=3; P<0.05 vs. control). CLCN3, chloride voltage-gated channel 3.

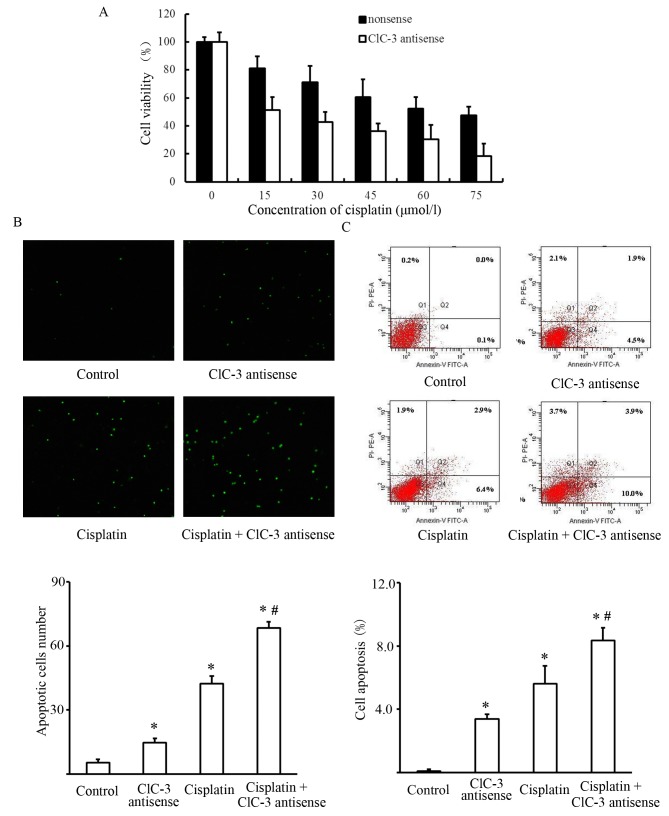

Silencing CLCN3 further reduces the viability of cisplatin-treated U251 cells

Changes in the viability of cisplatin-treated U251 cells were used to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of silencing CLCN3. Cells were transfected with nonsense or CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide for 24 h followed by treatment with cisplatin for 24 h. We observed a significant enhancement of the cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity following CLCN3 antisense transfection in U251 cells. Suppressing CLCN3 expression reduced cell viability at all concentrations of cisplatin tested (Fig. 2A). We also investigated whether CLCN3 antisense transfection enhanced cisplatin-induced apoptosis in U251 cells. Apoptosis quantification by flow cytometry was used to determine the apoptotic rate of cells treated with cisplatin and CLCN3 antisense. Early apoptotic cells were only labelled with Annexin V and shown in Q4 quadrant. The results showed that transfecting CLCN3 antisense before cisplatin treatment (15 µmol/l), increased the population of early apoptotic cells. Morphological determination of apoptosis by TUNEL staining also showed an increased induction of apoptosis following combined treatment (Fig. 2B and C).

Figure 2.

CLCN3 antisense reduces the viability of cisplatin-treated U251 cells. (A) Cell viability was measured by the MTT assay. Data are shown as means with standard deviations (SDs, bars) calculated from five separate experiments. (B) U251 cells treated with nonsense, CLCN3 antisense, Cisplatin or Cisplatin + CLCN3 antisense. Apoptotic nuclei (green) were identified by TUNEL staining (magnification, ×100). Data for the quantitative assessment of apoptosis are expressed as the mean apoptotic index ± SD. (C) Apoptotic cells stained positive for Annexin V-FITC and negative for PI (Q4 quadrant). Advanced apoptotic cells were stained positive for both Annnexin V-FITC and PI (Q2 quadrant). At advanced stages of apoptosis, cells were no longer viable. Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments run in triplicate. (n=3; *P<0.05 vs. control group, #P<0.05 vs. cisplatin group). CLCN3, chloride voltage-gated channel 3; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; PI, propidium iodide.

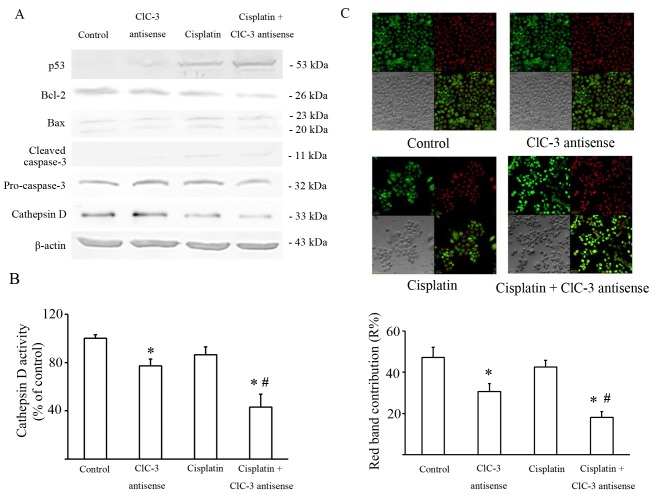

Effect of CLCN3 antisense transfection on cisplatin cytotoxicity and lysosome dysfunction

It is well known that cisplatin damages DNA by forming DNA adducts that induce the tumor suppressor TP53, which may lead to the induction of a number of processes, including apoptosis. The level of TP53 expression was detected by western blot, and the results showed that suppressing CLCN-3 induced a greater accumulation of TP53 in U251 cells treated with cisplatin. The ratio of BCL2 and BAX expression was also significantly decreased in U251 cells exposed to cisplatin with or without CLCN3 antisense transfection compared with the control group and the CLCN3 antisense group. Caspase 3 activity was significantly increased in U251 cells exposed to cisplatin with or without CLCN3 antisense compared with the control group (Fig. 3A; Table II).

Figure 3.

Effect of CLCN3 antisense transfection on cisplatin cytotoxicity and lysosome dysfunction. U251 cells were treated with or without cisplatin (15 µmol/l) for 24 h following transfection of nonsense or CLCN3 antisense. (A) Analysis of apoptotic pathways triggered by cisplatin and CLCN3 antisense. Western blot analysis of TP53, BCL2, BAX, Cathepsin D expression and caspase 3 cleavage. β-actin was used as the loading control. Values represent means of three independent experiments. (B) Cathepsin D activity in cell lysates. Values represent means of three independent experiments. (C) Effects of cisplatin and CLCN3 antisense on AO emission spectra in red-stained organelles. U251 cells were treated with or without cisplatin (15 µmol/l) for 12 h following transfection of nonsense or CLCN3 antisense. Fluorescence emission of AO from red-stained organelles after 30 min of incubation with AO (5 µmol/l). The contribution of the red band within the whole spectrum (R%) is shown. A total of 25 cells were analyzed for each condition. magnification ×400 (*P<0.05 vs. control group, #P<0.05 vs. cisplatin group). CLCN3, chloride voltage-gated channel 3; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; Bax, Bcl-2-associated protein X; AO, acridine orange.

Table II.

Status of different apoptosis relative genes in U251 cells.

| Groups | Control | CLCN3 antisense | Cisplatin | Cisplatin+CLCN3 antisense |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| p53/β-actin | 1.0±2.4 | 18.5±3.7a | 102.3±15.4a | 121.7±10.9a,b |

| Bcl-2/Bax | 1.0±0.12 | 1.02±0.24 | 0.36±0.14a | 0.24±0.08a,b |

| Pro-caspase 3/cleaved-caspase 3 | 1.0±0.47 | 1.10±0.32 | 4.49±0.91a | 6.68±0.84a,b |

Relative levels of different apoptosis relative genes calculated from intensities of bands are shown in Fig. 3A. Data show the means with standard deviations (SDs, bars) calculated from five separate experiments.

P<0.05 vs. control

P<0.05 vs. cisplatin by unpaired t-test. CLCN3, chloride voltage-gated channel 3; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; Bax, Bcl-2-associated protein X.

The intracellular chloride channel CLCN3 is expressed mainly in acidic intracellular compartments, especially lysosomes, and participates in their acidification (8). Lysosomal cathepsins, such as Cathepsin D, play key roles in the degradative function of lysosomes. So, the expression and the activity of lysosomal cathepsins are significant markers of lysosome function. Thus, Cathepsin D expression was also evaluated by western blot. These data showed that Cathepsin D expression decreased in U251 cells transfected by CLCN3 antisense with or without cisplatin (Fig. 3A). Cathepsin D activity was consistent with its expression (Fig. 3B).

AO preferentially accumulates in lysosomes and fluoresces red. When AO relocates from the lysosomes to the cytosol it fluoresces green. Staining with AO revealed that red granular fluorescence was decreased by CLCN3 antisense, but was not significantly altered by cisplatin. Furthermore, the combination of CLCN3 antisense transfection with cisplatin reduced red granular fluorescence more than cisplatin treatment alone (Fig. 3C).

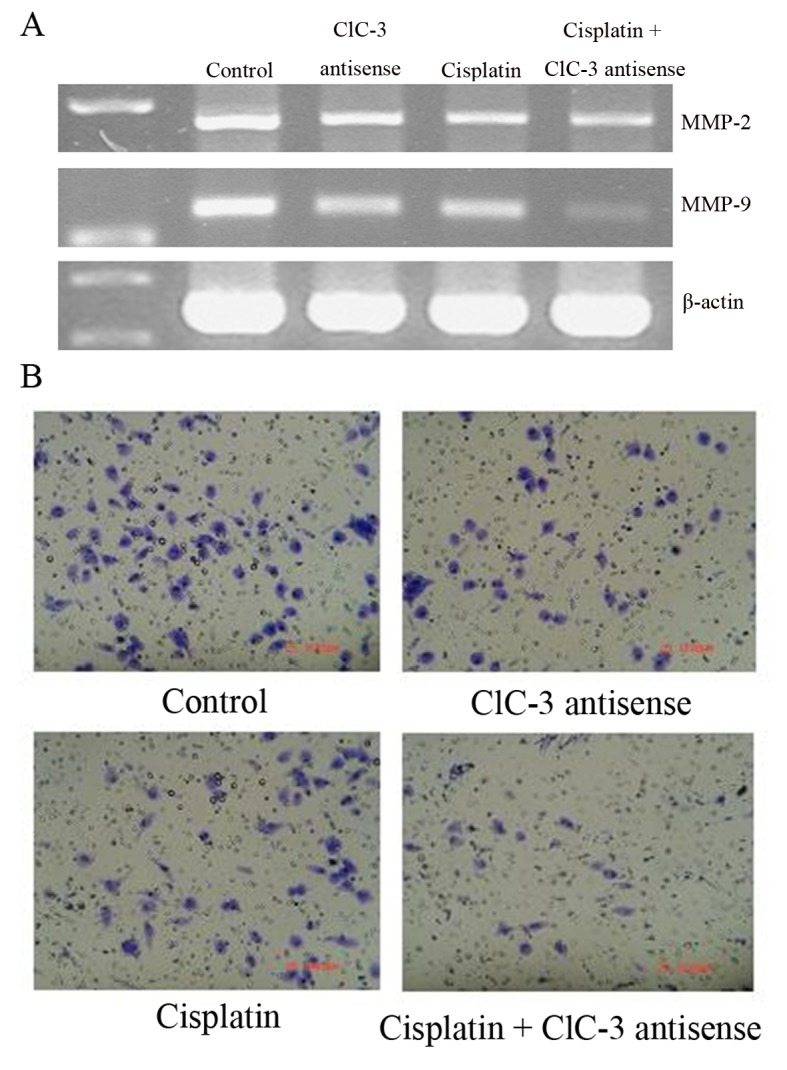

Effects of cisplatin and CLCN3 antisense treatment on MMP expression, invasion and mobility in U251 cells

The cell invasion and mobility-related genes, MMP2 and MMP9, were downregulated by cisplatin treatment with or without CLCN3 antisense transfection (Fig. 4A). Additionally, MMP2 and MMP9 expression were decreased by CLCN3 antisense transfection. Cell invasion and mobility were reduced by cisplatin with or without CLCN3 antisense transfection and by CLCN3 antisense alone (Fig. 4B; Table III).

Figure 4.

Effects of cisplatin treatment and CLCN3 antisense transfection on matrix metalloproteinase expression, invasion and motility in U251 cells. Cells were transfected and treated with or without cisplatin (15 µmol/l) for 24 h. (A) MMP2 and MMP9 mRNA expression were detected by RT-qPCR. (B) Treated cells were detached and added to the upper compartment of an invasion chamber. The cells that invaded through the Matrigel were determined by light microscopy after 24 h (bar=100 µm). CLCN3, chloride voltage-gated channel 3; MMP, matrix metalloprotease.

Table III.

Correlation analysis of MMP-2 and MMP-2 mRNA expression, cell invasion and cell mobility of U251 cells.

| Relative values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | MMP-2/β-actin | MMP-9/β-actin | Invasion cell number | Mobility optical density |

| Control | 1.00±0.14 | 1.00±0.11 | 81.0±4.6 | 0.81±0.02 |

| ClC-3 antisense | 0.61±0.17a | 0.64±0.25a | 42.0±4.4a | 0.58±0.13a |

| Cisplatin | 0.59±0.05a | 0.63±0.14a | 48.3±2.5a | 0.42±0.07a |

| Cisplatin+ClC-3 antisense | 0.59±0.27a | 0.29±0.09a,b | 12.7±5.1a,b | 0.31±0.11a,b |

Relative levels of MMP-2 and MMP-9 mRNA calculated from intensities of bands are shown in Fig. 5A. Relative numbers of invading cells calculated are shown in Fig. 5B. Treated cells were detached and resuspended in IMDM medium (5×105 cells/200 µl), and then added to the upper compartment of the invasion chamber without matrigel. The cells that invaded through the membrane of invasion chamber were measured with the MTT assay. Data show the means with standard deviations (SDs, bars) calculated from five separate experiments.

P<0.05 vs. control

P<0.05 vs. cisplatin by unpaired t-test. CLCN3, chloride voltage-gated channel 3; MMP, matrix metalloprotease.

Discussion

Cisplatin was the first clinically-applied platinum-based drug and has a potent DNA-damaging anticancer effect. It is well known that the primary cytotoxic action of cisplatin is due to its ability to form adducts with DNA and induce apoptosis (24). However, cancer cells with high intrinsic or acquired resistance to cisplatin are a major hurdle to its clinical success (25).

CLCN3 is primarily expressed on acidic intracellular compartments, especially lysosomes (3,8). It has been shown that CLCN3 protein is expressed at high levels in some tumors, including gliomas (26–29). These studies indicate that the function of CLCN3 is to facilitate lysosomal acidification and that it plays roles in proliferation, invasion, migration, and drug-resistance (30). The direct or indirect link between lysosomes and cisplatin resistance has been implied by several studies (31–33). Chloride channel blockers, such as 4-acetamido-4′-isothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (SITS) (34), and 4–4′-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid (DIDS) (35), are known to weaken cisplatin resistance; therefore, we investigated the relationship between cisplatin-induced apoptosis and chloride channel activity in human glioma cells.

In this study, we hypothesized that CLCN3 plays a role in cisplatin resistance in human glioma U251 cells via lysosomal dysfunction. To test our hypothesis, we utilized CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide transfection to suppress CLCN3 mRNA and protein expression in U251 cells. There are two classes of apoptosis induced by DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin: 1) the extrinsic receptor-dependent pathway (36) and 2) the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway (37). Cisplatin damages DNA by forming DNA adducts, which may then induce apoptotic TP53 responses (38). After DNA damage, if the damage is irreversible, apoptosis is triggered. Lysosomal dysfunction and membrane permeabilization cause the release of lysosomal enzymes into the cytosol in response to the action of cathepsins following p53 activation, thereby mediating cell death (39,40).

We investigated the effects of combined CLCN3 antisense oligonucleotide transfection and cisplatin treatment on U251 cells. Our results showed that cisplatin not only decreased cell viability but also induced apoptosis. We detected membrane phosphatidylserine translocation by Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) staining, DNA degradation by TUNEL staining, and p53 upregulation and caspase 3 activation by western blot. Our results illustrated that cisplatin induced cellular DNA fragmentation and triggered p53 accumulation. The altered BCL2/BAX expression ratio indicated activation of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization. Red granular fluorescence was decreased by CLCN3 antisense transfection, and was not significantly altered by cisplatin as shown by AO staining. CLCN3 antisense induced the lysosomal pH increasing in cisplatin-treated U251 cells. Moreover, Cathepsin D activity was decreased by CLCN3 suppression in U251 cells. These data suggested that CLCN3 suppression leaded to lysosomal dysfunction involved in mechanism of cisplatin-resistance in U251 cells. But the link between the lysosomal function and chemotherapeutic sensitivity still need further investigation.

In our previous study, we found that CLCN3 plays dual roles in the mechanisms of cisplatin resistance in U251 cells. On one hand, CLCN3 promotes the Akt/mTOR pathway through generating ROS via Nox, while on the other hand, as CLCN3 has indispensable roles in the acidification of acidic intracellular compartments such as late-endosomes, lysosomes and mature autophagosomes, CLCN3 deficiency probably induces autophagy (23). As a follow-up from the previously published article (23), in this study, we furthered our investigation into the possible roles of CLCN3 and discovered that suppressing CLCN3 induced lysosomal dysfunction, through increasing pH and decreasing Cathepsin D activity. Although our data indicated that CLC3 may provide possible targets for anticancer drugs, but one of limitations of our work must be pay attention to is that we only employed U251 cells in our study, so more research depending on various types cancer cells should be done to define the molecular mechanism of its activation.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81672948 and 81202552), Jilin Provincial Research Foundation for International Science and Technology Cooperation Projects, China, (grant no. 20160414005GH), Jilin University Bethune Plan B Projects (grant no. 2015222).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

JS and LZ conceived the idea and paper, reviewed the literature and examined the data. YHZ performed the vector construction experiments and wrote the manuscript. JJZ and LCZ participated in the qPCR and western blot experiments. XYY participated in the experiments of apoptosis evaluation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Sontheimer H. Malignant gliomas: Perverting glutamate and ion homeostasis for selective advantage. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:543–549. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jentsch TJ. Discovery of CLC transport proteins: Cloning, structure, function and pathophysiology. J Physiol. 2015;593:4091–4109. doi: 10.1113/JP270043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leanza L, Biasutto L, Managò A, Gulbins E, Zoratti M, Szabò I. Intracellular ion channels and cancer. Front Physiol. 2013;4:227. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Wang T, Zhao Z, Weinman SA. The ClC-3 chloride channel promotes acidification of lysosomes in CHO-K1 and Huh-7 cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C1483–C1491. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00504.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hara-Chikuma M, Yang B, Sonawane ND, Sasaki S, Uchida S, Verkman AS. ClC-3 chloride channels facilitate endosomal acidification and chloride accumulation. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1241–1247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weylandt KH, Nebrig M, Jansen-Rosseck N, Amey JS, Carmena D, Wiedenmann B, Higgins CF, Sardini A. ClC-3 expression enhances etoposide resistance by increasing acidification of the late endocytic compartment. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:979–986. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zifarelli G, Pusch M. CLC chloride channels and transporters: A biophysical and physiological perspective. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;158:23–76. doi: 10.1007/112_2006_0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong S, Bi M, Wang L, Kang Z, Ling L, Zhao C. CLC-3 channels in cancer (review) Oncol Rep. 2015;33:507–514. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lui VC, Lung SS, Pu JK, Hung KN, Leung GK. Invasion of human glioma cells is regulated by multiple chloride channels including ClC-3. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4515–4524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenberg B. Fundamental studies with cisplatin. Cancer. 1985;55:2303–23l6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850515)55:10<2303::AID-CNCR2820551002>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Madajewicz S, Chowhan N, Tfayli A, Roque C, Meek A, Davis R, Wolf W, Cabahug C, Roche P, Manzione J, et al. Therapy for patients with high grade astrocytoma using intraarterial chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Cancer. 2000;88:2350–2356. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2350::AID-CNCR20>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safaei R, Katano K, Larson BJ, Samimi G, Holzer AK, Naerdemann W, Tomioka M, Goodman M, Howell SB. Intracellular localization and trafficking of fluorescein-labeled cisplatin in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:756–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang XJ, Mukherjee S, Shen DW, Maxfield FR, Gottesman MM. Endocytic recycling compartments altered in cisplatin-resistant cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2346–2353. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safaei R, Howell SB. Copper transporters regulate the cellular pharmacology and sensitivity to Pt drugs. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao C, Hu B, Arno MJ, Panaretou B. Genomic screening in vivo reveals the role played by vacuolar H+ ATPase and cytosolic acidification in sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:416–425. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimada K, Li X, Xu G, Nowak DE, Showalter LA, Weinman SA. Expression and canalicular localization of two isoforms of the ClC-3 chloride channel from rat hepatocytes. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G268–G276. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.2.G268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen ML, Schade S, Lyons SA, Amaral MD, Sontheimer H. Expression of voltage-gated chloride channels in human glioma cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5572–5582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05572.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu SJ, Quan C, Li F, Vida L, Honig GR. Hematopoietic progenitor cells derived from embryonic stem cells: Analysis of gene expression. Stem Cells. 2002;20:428–437. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.20-5-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mizel SB. Interleukin 1 and T cell activation. Immunol Rev. 1982;63:51–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1982.tb00411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niinuma A, Higuchi M, Takahashi M, Oie M, Tanaka Y, Gejyo F, Tanaka N, Sugamura K, Xie L, Green PL, Fujii M. Aberrant activation of the interleukin-2 autocrine loop through the nuclear factor of activated T cells by nonleukemogenic human T-cell leukemia virus type 2 but not by leukemogenic type 1 virus. J Virol. 2005;79:11925–11934. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11925-11934.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan L, Aoyagi M, Tamaki M, Nakagawa K, Nagashima G, Nagasaka Y, Ohno K, Yamamoto K, Hirakawa K. Sensitization of human malignant glioma cell lines to tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis by cisplatin. J Neurooncol. 2001;52:23–36. doi: 10.1023/A:1010685110862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Millot C, Millot JM, Morjani H, Desplaces A, Manfait M. Characterization of acidic vesicles in multidrug-resistant and sensitive cancer cells by acridine orange staining and confocal microspectrofluorometry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1997;45:1255–1264. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Su J, Xu Y, Zhou L, Yu HM, Kang JS, Liu N, Quan CS, Sun LK. Suppression of chloride channel 3 expression facilitates sensitivity of human glioma U251 cells to cisplatin through concomitant inhibition of Akt and autophagy. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2013;296:595–603. doi: 10.1002/ar.22665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strojan P, Vermorken JB, Beitler JJ, Saba NF, Haigentz M, Jr, Bossi P, Worden FP, Langendijk JA, Eisbruch A, Mendenhall WM, et al. Cumulative cisplatin dose in concurrent chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer: A systematic review. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E2151–E2158. doi: 10.1002/hed.24026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borst P, Rottenberg S, Jonkers J. How do real tumors become resistant to cisplatin? Cell Cycle. 2008;7:1353–1359. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.10.5930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao J, Chen L, Xu B, Wang L, Li H, Guo J, Li W, Nie S, Jacob TJ, Wang L. Suppression of ClC-3 channel expression reduces migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:1706–1716. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sontheimer H. An unexpected role for ion channels in brain tumor metastasis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233:779–791. doi: 10.3181/0711-MR-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Habela CW, Olsen ML, Sontheimer H. ClC3 is a critical regulator of the cell cycle in normal and malignant glial cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9205–9217. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1897-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moreland JG, Davis AP, Bailey G, Nauseef WM, Lamb FS. Anion channels, including ClC-3, are required for normal neutrophil oxidative function, phagocytosis, and transendothelial migration. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12277–12288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu T, Lee EL, Ise T, Okada Y. Volume-sensitive Cl(−) channel as a regulator of acquired cisplatin resistance. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:75–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Safaei R, Larson BJ, Cheng TC, Gibson MA, Otani S, Naerdemann W, Howell SB. Abnormal lysosomal trafficking and enhanced exosomal export of cisplatin in drug-resistant human ovarian carcinoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1595–1604. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chauhan SS, Liang XJ, Su AW, Pai-Panandiker A, Shen DW, Hanover JA, Gottesman MM. Reduced endocytosis and altered lysosome function in cisplatin-resistant cell lines. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1327–1334. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garmann D, Warnecke A, Kalayda GV, Kratz F, Jaehde U. Cellular accumulation and cytotoxicity of macromolecular platinum complexes in cisplatin-resistant tumor cells. J Control Release. 2008;131:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yarbrough JW, Merryman JI, Barnhill MA, Hahn KA. Inhibitors of intracellular chloride regulation induce cisplatin resistance in canine osteosarcoma cells. In Vivo. 1999;13:375–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee EL, Shimizu T, Ise T, Numata T, Kohno K, Okada Y. Impaired activity of volume-sensitive Cl-channel is involved in cisplatin resistance of cancer cells. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:513–521. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashkenazi A. Targeting death and decoy receptors of the tumour-necrosis factor superfamily. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:420–430. doi: 10.1038/nrc821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang X, Wang X. Cytochrome C-mediated apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:87–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burger H, Nooter K, Boersma AW, Kortland CJ, Stoter G. Expression of p53, Bcl-2 and Bax in cisplatin-induced apoptosis in testicular germ cell tumour cell lines. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1562–1567. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jäättelä M, Candé C, Kroemer G. Lysosomes and mitochondria in the commitment to apoptosis: A potential role for cathepsin D and AIF. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:135–136. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boya P, Kroemer G. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization in cell death. Oncogene. 2008;27:6434–6451. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.