Abstract

The use of bronchoscopy is central to the diagnosis of lung cancer. However, the sensitivity of bronchoscopy is low. In addition, bronchial washing cytology, which is a routine adjunctive test, does not significantly improve the performance of bronchoscopy owing to its low sensitivity. To enhance the diagnostic performance of bronchoscopy, the protocadherin GA12 (PCDHGA12) methylation biomarker in bronchial washings was introduced as a novel adjunctive diagnostic test. A total of 98 patients who underwent bronchoscopy owing to suspicion of lung cancer were analyzed. Cytological examination and PCDHGA12 methylation biomarker testing of the bronchial washing fluid were performed. The performance of the tests was analyzed. The final diagnosis in 60 patients was lung cancer and in 38 patients was benign disease. The PCDHGA12 methylation biomarker had a sensitivity of 75.0%, a specificity of 78.9% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of 84.9%, whereas cytological assessment had a sensitivity of 45.0%, a specificity of 92.1% and a PPV of 90%. Patients with positive PCDHGA12 methylation test had an odds ratio for lung cancer of 11.25 (confidence interval, 4.25–29.8) compared with negative subjects. The combination of the two tests exhibited an increased sensitivity (83.3%), a specificity of 71.1% and a PPV of 82.0%. Furthermore, considering the non-diagnostic bronchoscopy group alone, the test demonstrated a sensitivity of 61.9% and a specificity of 78.9%. The results of the present study demonstrated that PCDHGA12 methylation, as a lung cancer biomarker in bronchial washings, may be a used as an adjunctive test to bronchoscopy.

Keywords: lung cancer, bronchoscopy, protocadherin GA12, biomarker

Introduction

Bronchoscopy is one of the most important diagnostic procedures in patients with a suspicion of lung cancer; however, the diagnostic performance of bronchoscopy is unsatisfactory, with detection sensitivity for peripherally located lesions being as low as 34% (1). Furthermore, bronchial washing cytology, a routine adjunctive test, does not significantly improve the performance of bronchoscopy owing to its low sensitivity for peripheral lesions (28–32%) (2,3). In patients who have not been diagnosed by bronchoscopy, further diagnostic procedures or regular radiological studies are frequently required (1). Diagnostic procedures, including transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy or surgical lung biopsy, carry a significant risk of complications, such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, or mortality (4,5). Using imaging surveillance, the diagnosis of lung cancer may be delayed, which is undesirable.

Although numerous clinical and radiographic markers associated with malignancy have been identified, distinguishing between benign and malignant nodules remains challenging (6). For clinicians, it is difficult to select between imaging surveillance and invasive procedures when bronchoscopy results are negative. For these reasons, a novel diagnostic test with higher sensitivity than bronchial washing cytology that may enhance the diagnostic performance of bronchoscopy is required.

The regulation of homophilic cell-adhesion proteins, termed protocadherins, is associated with tissue development and growth (7). The epigenetic inactivation of genes that code for protocadherins is associated with the development and growth of several malignant tumor types (8,9). The protocadherin GA12 (PCDHGA12) gene, one of the genes coding for protocadherin, is located on chromosome 5 (10). Hypermethylation of PCDHGA12 is associated with several types of cancer, including Wilms tumor, leukemia and lung cancer (11–13). Previously, the hypermethylation of PCDHGA12 was observed in lung cancer (14). Although the underlying molecular mechanism is unknown, we postulated that PCDHGA12 may be used as a lung cancer biomarker.

In the present study, the use of PCDHGA12 methylation biomarker in bronchial washing specimens was evaluated as an adjunctive diagnostic tool to bronchoscopy in lung cancer, compared with washing cytology.

Materials and methods

Study population

This prospective study was conducted at Konyang University Hospital, Daejeon, Republic of Korea. Between January 2016 to July 2016, patients with suspected lung cancer were recruited, regardless of their smoking status. A total of 107 patients suspected to have lung cancer that underwent bronchoscopy with bronchial washing were enrolled in the present study. The mean age was 66.9 years (age range, 26–90 years), 68.2% of the patients were male (n=73) and 31.8% of the patients were female (n=34). Exclusion criteria included a concurrent cancer or history of lung cancer, an age <18 years old. All participants provided written informed consent and the study was approved by the Konyang University Hospital Institutional Review Board (Daejeon, Republic of Korea; 2015-08-020). The clinical data of the patients were obtained prospectively. In order to avoid incorrect diagnosis for the ambiguous lesion at initial work up, final diagnoses were made following a 6-month follow-up. Staging was performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system (15).

Sample collection and cytology

Flexible bronchoscopy was performed by pulmonologists, and all bronchial washing samples were obtained in a routine manner during bronchoscopy. Briefly, 5–10 ml of normal saline was injected two or three times, and at least 10 ml of fluid was retrieved. The majority of the fluid sample was sent for cytological examination and other routine laboratory tests, and 3–5 ml of the fluid sample was sent to test for the PCDHGA12 methylation biomarker. Cytology results were considered as positive not only for definite malignant cells but also atypical cells.

Methylation measurement in DNA by linear target enrichment-quantitative methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Genomic DNA was isolated from bronchial aspirate samples using the QiaAmp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Bisulfite treatment of genomic DNA was performed using the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research Corp., Irvine, CA, USA). For the measurement of PCDHGA12 methylation, linear target enrichment was introduced in order to specifically enrich methylated PCDHGA12 target DNA from bisulfite modified DNA. Collagen type II α1 chain (COL2A1) was used as a control gene to assess the adequacy of bisulfite conversion and PCR in each sample. A reaction mixture of 20 µl contained 15 ng bisulfite-converted DNA, each 0.07 µM PCDHGA12 methylation-specific antisense and internal control COL2A1 gene-specific antisense primers attached to the 5′ universal sequence and 3 µl of 5X AptaTaq PCR master mix (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min followed by 5 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec. Following linear target enrichment, the reaction mixture volume was scaled up to 20 µl, containing 4 µl 5X AptaTaq PCR master mix, 0.5 µM PCDHGA12 methylation-specific sense primer, 0.25 µM PCDHGA12 probe (FAM; fluorescein amidite), 0.4 µM COL2A1 sense primer, 0.2 µM o COL2A1 probe (Cy5) and 0.5 µM universal sequence primer. Quantitative PCR was performed using an AB7500 FAST cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 5 min and then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec. For each run, bisulfite-converted methylated and unmethylated genomic DNA (Qiagen GmbH) were used as methylation controls. A non-template control was also included. Cycle quantification (Cq) value was calculated using 7500 software v. 2.3 (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) (16). The sequences of primers and probes are listed in Table I. The percentage of methylated reference (PMR) was defined as the percentage of fully methylated molecules at a specific locus of the PCDHGA12 gene, as described previous (17).

Table I.

Primer and probe sequences.

| Gene | Primers and probes | Sequences, 5′-3′ |

|---|---|---|

| PCDHGA12 | Sense | ATTCGGTICGTATAGGTATCGC |

| Anti-sense | CAAATTCTCCGAAACGITCGCG | |

| Probe | FAM-CGTATTCGCGTGATGGTTTTGGATGC-Iowa Black | |

| COL2A1 | Sense | GTAATGTTAGGAGTATTTTGTGGITA |

| Anti-sense | CTAICCCAAAAAAACCCAATCCTA | |

| Probe | Cy5-AGAAGAAGGGAGGGGTGTTAGGAGAGG-Iowa Black | |

| Universal | ACTGATAAGGCGACCACCGA |

PCDHGA12, protocadherin GA12; FAM, fluorescein amidite; I, inosine nucleotide; COL2A1, collagen type II α1 chain.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc version 9.3.2.0 (MedCalc Software BVBA, Ostend, Belgium). A threshold PMR value was determined to discriminate between non-cancerous and lung cancer samples by receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Area under curve (AUC), 95% confidence interval (CI) and P-values were calculated. Kruskal-Wallis test were performed to compare methylation levels. Summary statistics are reported as medians and standard variations for continuous variables and as proportions for categorical variables. χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used for categorical variables and Student's t-test was used for the analysis of continuous variables. Three experimental repeats were performed. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Clinical and demographic characteristics

Of the 107 patients, 6 patients had no final diagnosis and the specimens of 3 patients were not suitable for analysis. Thus, 9 patients were excluded from the present study and a total of 98 patients were analyzed. Of these patients, 60 were confirmed to have lung cancer and 38 were diagnosed with benign disease. Patients with lung cancer were significantly older than those with benign disease (P=0.004), and a larger proportion of them were current or former smokers. Squamous cell carcinoma was the most frequent type of cancer observed, and all patients with small cell lung cancer exhibited extensive stage disease (Table II).

Table II.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients.

| Characteristic | Lung cancer, n | Benign, n | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 60 | 38 | |

| Sex | 0.377 | ||

| Female | 17 | 14 | |

| Male | 43 | 24 | |

| Age, years | 70.4±9.8 | 62.1±14.8 | 0.004 |

| Smoking status | 0.026 | ||

| Never | 14 | 17 | |

| Current or former | 46 | 21 | |

| Median tobacco use, pack-yearsa | 38.5±18.6 | 36.4±12.9 | 0.647 |

| PCDHGA12 methylation | <0.001 | ||

| Positive | 45 | 8 | |

| Negative | 15 | 30 | |

| Lung-cancer histologic type | |||

| Squamous | 23 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 20 | ||

| Large-cell | 2 | ||

| NSCLC not otherwise specified | 4 | ||

| Small-cell | 11 | ||

| Lung-cancer location type | |||

| Central | 36 | ||

| Peripheral | 24 | ||

| Lung-cancer stage (NSCLC) | |||

| Stage I | 7 | ||

| Stage II | 11 | ||

| Stage III | 10 | ||

| Stage IV | 21 | ||

| Lung cancer stage (SCLC) | |||

| Limited | 0 | ||

| Extensive | 11 |

Mean ± standard deviation. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer; PCDHGA12, protocadherin GA12.

Diagnostic performance of PCDHGA12 gene

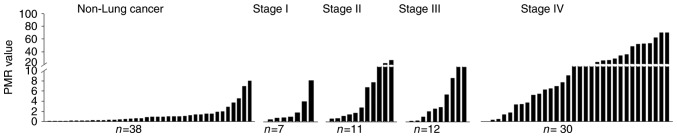

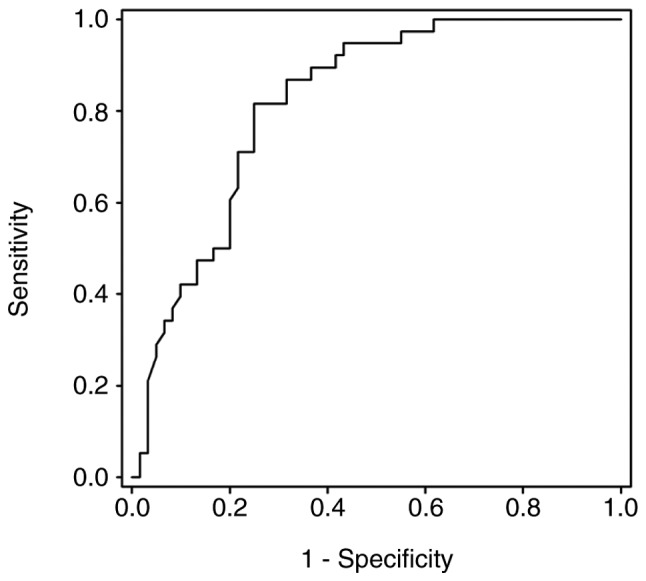

Methylation status of the PCDHGA12 gene in bronchial aspirates (Fig. 1) and a ROC curve were depicted (Fig. 2). This curve had an AUC of 0.819 (P<0.001). The threshold value of PMR for a methylation-positive result was determined as 1.52.

Figure 1.

Methylation investigation results of the PCDHGA12 gene for detecting lung cancer in bronchial aspirates. Methylation status of the PCDHGA12 gene is plotted as PMR values. All small cell lung cancer cases having extensive stage disease were plotted as stage IV. PMR, percentage of methylated reference; PCDHGA12, protocadherin GA12.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for the protocadherin GA12 gene for detecting lung cancer in bronchial aspirate samples. Area under the curve=0.819, significant at P<0.0001.

The diagnostic performance of the PCDHGA12 methylation test is presented in Table III. The methylation biomarker demonstrated an improved sensitivity and negative predictive value compared with cytology. In addition, a combination of the two tests exhibited an improved diagnostic performance.

Table III.

Performance of the methylation test, cytology and the two in combination.

| Type | Sensitivity, % (CI) | Specificity, % (CI) | PPV, % (CI) | NPV, % (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation | 75.0 (61.8–84.8) | 78.9 (62.2–89.8) | 84.9 (71.6–92.8) | 66.7 (50.9–79.5) |

| Cytology | 45.0 (32.3–58.3) | 92.1 (32.3–58.3) | 90.0 (72.3–97.3) | 51.4 (39.1–60.9) |

| Combined | 83.3 (71.0–91.2) | 71.1 (53.8–84.0) | 82.0 (69.6–90.2) | 72.9 (55.6–85.6) |

CI, 95% confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Table IV depicts the results of subgroup analysis in patients with lung cancer. The sensitivity of washing cytology for peripheral lung lesions was decreased compared with that for central lesions. However, there was no significant difference observed between the sensitivity of the methylation test for peripheral lesions and central lesions. A combination of cytology analysis and the methylation test demonstrated improved sensitivity for peripheral and central lesions. The type of tumor cell was not associated with differences in sensitivity of the methylation test or cytology. The sensitivity of the methylation biomarker was increased in the advanced stage group compared with the early stage group.

Table IV.

Sensitivity of cytology, methylation test, and the two in combination in patients with lung cancer.

| Category | Sub-category | Patients, n | Methylation sensitivity, % (CI) | Cytology sensitivity, % (CI) | Combined sensitivity, % (CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer location | Central | 36 | 83.3 (66.5–93.0) | 63.9 (46.2–78.7) | 94.4 (80.0–99.0) |

| Peripheral | 24 | 62.5 (40.8–80.4) | 16.7 (5.48–38.2) | 66.7 (44.7–83.6) | |

| P-value | 0.065 | <0.001 | 0.007 | ||

| Histology | SCLC | 11 | 90.9 (57.1–99.5) | 36.3 (12.3–68.4) | 90.9 (57.1–99.5) |

| NSCLC | 49 | 71.4 (56.5–83.0) | 46.9 (32.8–67.2) | 81.6 (67.5–90.8) | |

| P-value | 0.169 | 0.385 | 0.409 | ||

| Stage | I–IIIa | 20 | 50.0 (27.8–72.1) | 40.0 (19.9–63.5) | 70.0 (45.6–87.1) |

| IIIb-IV | 40 | 87.5 (72.3–95.3) | 47.5 (31.8–63.6) | 90.0 (75.4–96.7) | |

| P-value | 0.028 | 0.183 | 0.033 |

CI, 95% confidence interval; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

A total of 59 patients were not diagnosed by bronchoscopy with cytology. These patients were designated as the non-diagnostic bronchoscopy group. Of these patients, 21 were ultimately diagnosed with lung cancer and 38 patients were diagnosed with benign disease. The diagnostic performance of the PCDHGA12 methylation test for the non-diagnostic bronchoscopy group had a sensitivity of 61.9% (CI, 38.7–81.0%), a specificity of 78.9% (CI, 62.2–89.9%), and a positive predictive value of 61.9% (CI, 38.7–81.0%).

Discussion

Epigenetic alterations have been demonstrated to serve a function in lung cancer development. These features can be used in the clinical field of diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutics (18). Hundreds of genes, including DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 3A, δ-like non-canonical notch ligand 1, tumor suppressor candidate 3 and fragile histidine triad, have been recognized to harbor dense methylation in the promoter region in lung cancer (19–22). The PCDHGA12 gene is one of these genes, and it has been demonstrated to be associated with several types of cancer, including lung cancer (11–13). As such, the PCDHGA12 gene possesses a potential benefit as a biomarker in several types of cancer (23,24). However, to the best of our knowledge, the methylation status of PCDHGA12 has yet to been studied as a single biomarker in lung cancer. It was previously observed that several clusters of the PCDH gene family experience a significant level of aberrant hypermethylation in human lung cancer cells, and the methylation status of PCDHGA12 might be a novel biomarker for the detection of lung cancer (14). On the basis of this observation the present study aimed to evaluate the usefulness of the PCDHGA12 methylation biomarker as an adjunctive diagnostic tool using bronchial washing specimens. The results of the present study reaffirmed the association between PCDHGA12 methylation and lung cancer, and demonstrated its usefulness as an adjunctive test to bronchoscopy.

Although bronchial washing cytology is able to provide a pathological diagnosis, its sensitivity is unsatisfactory (25). Low sensitivity is most commonly caused by a sampling error when obtaining the specimen (1). As bronchial washing is an abrasive type of cytology, the washing fluid should contain tumor cells and an adequate number of cells for an accurate diagnosis. If the tumor is located peripherally, it is not possible to visualize the lesion directly and it is necessary to select the bronchus that communicates with the tumor (26); however, it is difficult to determine the correct bronchus, meaning that the likelihood of retrieving tumor cells decreases. Another reason for the low sensitivity is in interpretation (27–29). Compared with the resection specimens, in the washing cytology samples, interpretation based on histology is not possible (27). This often results in incorrect recognition of malignant cells, resulting in false-negative interpretations (25,28). Furthermore, only positive results provide usable information, with negative reports being inconclusive (29). A previous study estimated that a cytopathological association is absent in ~40% of cases (30).

DNA methylation assays do not experience the aforementioned limitations for several reasons. First, PCR-based methylation tests are sensitive enough to detect even a limited number of methylated DNA molecules in a background of excess normal DNA molecules (31). Second, as field cancerization is observed in lung cancer (32), tumor cells and the surrounding normal bronchial epithelial cells may be useful specimens. Thus, the necessity of selecting the appropriate bronchus is eliminated. Third, DNA methylation is a laboratory test, and the percentage of methylated reference is calculated by a computer, meaning the results are not affected by the ability of the pathologist.

Recently, a novel bronchial genomic classifier using RNA microarray was developed (33). It used bronchial epithelial cell samples obtained by bronchoscopic cytology brushes. The genomic classifier demonstrated a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 47% (34). The diagnostic performance of PCDHGA12 methylation test observed in the present study was similar to this previously studied RNA microarray-based method. DNA methylation possesses a number of advantages over the RNA microarray method. First, DNA is more chemically stable than RNA, meaning it is easier to handle. Second, DNA methylation test is cheaper than microarray, with microarray not being routinely used owing to the high cost. Third, since the bronchoalveolar-washing specimen is a useful sample for lung cancer biomarker identification (35), the DNA methylation assay does not require brushing.

In the present study, the PCDHGA12 methylation biomarker demonstrated improved sensitivity compared with cytology. The combination of the two tests improved the diagnostic performance. The sensitivity of the methylation biomarker was increased in advanced stage compared with early stage. It may be assumed that the patients with advanced staging experienced an increased tumor burden that may enhance the sensitivity. However, the sensitivity of the methylation test was also improved in early-stage patients compared with cytology.

As smoking is a potent risk factor of lung cancer and has demonstrated a marked association with DNA epigenetics (36), certain previous studies only included patients with smoking history (33,34). In order to apply the PCDHGA12 methylation test to all patients who are suspected of possessing lung cancer, non-smokers were also included in the present study. The methylation biomarker exhibited a favorable performance, even though non-smokers were included. Furthermore, the sensitivity of the techniques between the smoking and non-smoking patients was not different.

The sample size of the present study was small, with limited statistical power. As this was the first study to investigate PCDHGA12 methylation status in bronchial washings, to the best of our knowledge, further studies are required to validate the results presented. A final diagnosis was made 6 months after bronchoscopy, which is a relatively short period of time to diagnose ambiguous pulmonary lesions. Despite having excluded all inconclusive cases, the 6-month observation or follow-up may have resulted in misdiagnosis or unnecessary exclusion at the time of enrollment.

In conclusion, PCDHGA12 methylation in bronchial washing specimens may be an adjunctive diagnostic tool to bronchoscopy in lung cancer. The test demonstrates an improved diagnostic performance compared with cytology. Further studies are required to validate and assess the usefulness of the test.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Korean Government (grant no. NRF-2015R1D1A1A01061040) and by Konyang University Myunggok Research Fund (grant no. 2015-07).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

IJ and YY were the primary investigators and had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. IJ, YY, SP, EC, MN, SK, JK, TO, SA, CP, YK, DP and JS were involved in data generation analysis and interpretation of the data and in the preparation or critical revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing and revising of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent and the present study was approved by the Konyang University Hospital Institutional Review Board (Daejeon, Republic of Korea; approval no. 2015-08-020).

Consent for publication

All patients in the present study provided written informed consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Rivera MP, Mehta AC, Wahidi MM. Establishing the diagnosis of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd Ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(Suppl 5):e142S–e165S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reichenberger F, Weber J, Tamm M, Bolliger CT, Dalquen P, Perruchoud AP, Solèr M. The value of transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of peripheral pulmonary lesions. Chest. 1999;116:704–708. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buccheri G, Barberis P, Delfino MS. Diagnostic, morphologic, and histopathologic correlates in bronchogenic carcinoma. A review of 1,045 bronchoscopic examinations. Chest. 1991;99:809–814. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.4.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith MA, Battafarano RJ, Meyers BF, Zoole JB, Cooper JD, Patterson GA. Prevalence of benign disease in patients undergoing resection for suspected lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1824–1828. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiener RS, Wiener DC, Gould MK. Risks of transthoracic needle biopsy: How high? Clin Pulm Med. 2013;20:29–35. doi: 10.1097/CPM.0b013e31827a30c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gould MK, Donington J, Lynch WR, Mazzone PJ, Midthun DE, Naidich DP, Wiener RS. Evaluation of individuals with pulmonary nodules: When is it lung cancer? Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd Ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(Suppl 5):e93S–e120S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hulpiau P, van Roy F. Molecular evolution of the cadherin superfamily. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:349–369. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dang Z, Shangguan J, Zhang C, Hu P, Ren Y, Lv Z, Xiang H, Wang X. Loss of protocadherin-17(PCDH-17) promotes metastasis and invasion through hyperactivation of EGFR/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:2527–2535. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3970-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen T, Long B, Ren G, Xiang T, Li L, Wang Z, He Y, Zeng Q, Hong S, Hu G. Protocadherin20 acts as a tumor suppressor gene: Epigenetic inactivation in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116:1766–1775. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Q, Maniatis T. A striking organization of a large family of human neural cadherin-like cell adhesion genes. Cell. 1999;97:779–790. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dallosso AR, Hancock AL, Szemes M, Moorwood K, Chilukamarri L, Tsai HH, Sarkar A, Barasch J, Vuononvirta R, Jones C, et al. Frequent long-range epigenetic silencing of protocadherin gene clusters on chromosome 5q31 in Wilms' tumor. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000745. doi: 10.1371/annotation/012d5a44-8239-4057-8c3b-3dc159ea3a02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor KH, Pena-Hernandez KE, Davis JW, Arthur GL, Duff DJ, Shi H, Rahmatpanah FB, Sjahputera O, Caldwell CW. Large-scale CpG methylation analysis identifies novel candidate genes and reveals methylation hotspots in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2617–2625. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu Y, Lemon W, Liu PY, Yi Y, Morrison C, Yang P, Sun Z, Szoke J, Gerald WL, Watson M, et al. A gene expression signature predicts survival of patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An SW, Moon YH, Oh TJ, Lee MK, Lee CH, Lee SY, Lee SH. Identification of hypermethylation of PCDHGA12 gene by genome-wide analysis as a novel diagnostic marker of lung cancer. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res (AACR Annual Meeting) 2009;69:3357. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th edition. Springer; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eads CA, Lord RV, Wickramasinghe K, Long TI, Kurumboor SK, Bernstein L, Peters JH, DeMeester SR, DeMeester TR, Skinner KA, Laird PW. Epigenetic patterns in the progression of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3410–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langevin SM, Kratzke RA, Kelsey KT. Epigenetics of lung cancer. Transl Res. 2015;165:74–90. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Yao J, Sun H, He K, Tong D, Song T, Huang C. MicroRNA-101 suppresses progression of lung cancer through the PTEN/AKT signaling pathway by targeting DNA methyltransferase 3A. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:329–338. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.5423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhong Z, Ye Y, Guo W, He Y, Hu W. Relationship between DLK1 gene promoter region DNA methylation and non-small cell lung cancer biological behavior. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4123–4126. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Duppel U, Woenckhaus M, Schulz C, Merk J, Dietmaier W. Quantitative detection of TUSC3 promoter methylation-a potential biomarker for prognosis in lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:3004–3012. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czarnecka KH, Migdalska-Sęk M, Domańska D, Pastuszak-Lewandoska D, Dutkowska A, Kordiak J, Nawrot E, Kiszałkiewicz J, Antczak A, Brzeziańska-Lasota E. FHIT promoter methylation status, low protein and high mRNA levels in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Oncol. 2016;49:1175–1184. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2016.3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang MX, Wang HY, Zhao X, Srilatha N, Zheng D, Shi H, Ning J, Duff DJ, Taylor KH, Gruner BA, Caldwell CW. Molecular detection of B-cell neoplasms by specific DNA methylation biomarkers. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:265–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinert T, Modin C, Castano FM, Lamy P, Wojdacz TK, Hansen LL, Wiuf C, Borre M, Dyrskjøt L, Orntoft TF. Comprehensive genome methylation analysis in bladder cancer: Identification and validation of novel methylated genes and application of these as urinary tumor markers. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5582–5592. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Girard P, Caliandro R, Seguin-Givelet A, Lenoir S, Gossot D, Validire P, Stern JB. Sensitivity of cytology specimens from bronchial aspirate or washing during bronchoscopy in the diagnosis of lung malignancies: An update. Clin Lung Cancer. 2017;18:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Funahashi A, Browne TK, Houser WC, Hranicka LJ. Diagnostic value of bronchial aspirate and postbronchoscopic sputum in fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Chest. 1979;76:514–517. doi: 10.1378/chest.76.5.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones AM, Hanson IM, Armstrong GR, O'Driscoll BR. Value and accuracy of cytology in addition to histology in the diagnosis of lung cancer at flexible bronchoscopy. Respir Med. 2001;95:374–378. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Idowu MO, Powers CN. Lung cancer cytology: Potential pitfalls and mimics-a review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:367–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajdu SI, Melamed MR. Limitations of aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of primary neoplasms. Acta Cytol. 1984;28:337–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rao S, Lal A, Barathi G, Dhanasekar T, Duvuru P. Bronchial wash cytology: A study on morphology and morphometry. J Cytol. 2014;31:63–67. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.138664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki M, Yoshino I. Aberrant methylation in non-small cell lung cancer. Surg Today. 2010;40:602–607. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadara H, Wistuba II. Field cancerization in non-small cell lung cancer: Implications in disease pathogenesis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2012;9:38–42. doi: 10.1513/pats.201201-004MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitney DH, Elashoff MR, Porta-Smith K, Gower AC, Vachani A, Ferguson JS, Silvestri GA, Brody JS, Lenburg ME, Spira A. Derivation of a bronchial genomic classifier for lung cancer in a prospective study of patients undergoing diagnostic bronchoscopy. BMC Med Genomics. 2015;8:18. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silvestri GA, Vachani A, Whitney D, Elashoff M, Smith Porta K, Ferguson JS, Parsons E, Mitra N, Brody J, Lenburg ME, et al. A bronchial genomic classifier for the diagnostic evaluation of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:243–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uribarri M, Hormaeche I, Zalacain R, Lopez-Vivanco G, Martinez A, Nagore D, Ruiz-Argüello MB. A new biomarker panel in bronchoalveolar lavage for an improved lung cancer diagnosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:1504–1512. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allione A, Marcon F, Fiorito G, Guarrera S, Siniscalchi E, Zijno A, Crebelli R, Matullo G. Novel epigenetic changes unveiled by monozygotic twins discordant for smoking habits. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128265. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.