1. Introduction

Iatrogenic venous graft occlusion is a rare but very serious and potentially fatal procedure-related complication of a diagnostic coronary and graft angiography. Management of this event may vary from conservative to percutaneous and even to redo coronary bypass surgery depending on the type of the occlusion or dissection and patient's hemodynamic status.

We present a case of the non-ST elevation myocardial infarction patient who suffered an acute iatrogenic graft occlusion by the diagnostic catheter during angiography with subsequent successful retrograde graft recanalization through the previously stented anastomosis. To our knowledge, this is the first described successful retrograde recanalization of acute iatrogenic venous graft occlusion through the stented anastomosis in a patient with acute coronary syndrome and previous coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

2. Case report

A 69-year-old male was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit with an acute onset of chest pain, nausea, and dyspnea. His history is significant for diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CABG surgery in 2004 and obtuse marginal (OM) venous graft anastomosis stenting in 2014. Symptoms quickly resolved after antianginal and antithrombotic therapy initiation, electrocardiogram was unremarkable, bedside echo showed mild lateral hypokinesia with normal ejection fraction, and after the initial positive troponin test (0.67 ng/ml) patient was admitted to cathlab for diagnostic angiography. In the coronary syndrome setting, we routinely use femoral access in the majority of graft angiographies and femoral artery access was obtained under local anesthesia in this case also. Left and right coronary artery angiographies were quick and unremarkable and shortly thereafter venous grafts to right coronary artery and OM as well as left internal mammary artery (LIMA) angiographies had been performed—LIMA was not used during CABG and patient had two venous grafts overall. The syndrome-related problem was in the distal OM venous graft anastomosis with significant OM graft ostium lesion, which was fully engaged by the catheter (Fig. 1). Just before the LIMA and after the OM cine, the patient complained about chest pain recurrence, but the operator proceeded to LIMA cine. After the LIMA cine, patient's chest pain worsened, he became anxious, rapid ST-segment elevation was noticed on cardiac monitor and immediate OM graft angiography demonstrated acute total ostial occlusion (Fig. 2). Shortly thereafter patient's hemodynamic condition quickly deteriorated with subsequent ventricular fibrillation. Immediate defibrillation and resuscitation had been performed and the patient was intubated after proper sedation. The patient had already received 180 mg of ticagrelor at the moment of angiography and 10,000 IU of heparin were administered immediately after the occlusion occurred. Diagnostic catheter was changed to guide catheter JR 3.5 SH 6F (Cordis, Piscataway, NJ) and multiple attempts failed to cross the occlusion. After 20 min of unsuccessful intervention, we switched to native OM anterograde recanalization. With XB 3.5 SH 6F (Cordis, Piscataway, NJ) guide catheter and coronary wire Miracle 3 (Asahi Intecc, Nagoya, Japan), we attempted to cross the chronic total occlusion (CTO) with Miracle 6 (Asahi Intecc, Nagoya, Japan) wire escalation, but also failed after another 30 min. Patient's condition remained stable with persistent ST elevation on cardiac monitor. After all unsuccessful attempts to recanalize graft and native artery, we decided to use retrograde approach to open the venous graft. Through the right radial access, we engaged the left main coronary artery with XB 3.5 SH 6F, graft ostium with JR 3.5 and with some technical difficulties managed to cross a small portion of the OM CTO and retrogradely find the true lumen of venous anastomosis through the stent struts. Wire passed directly to the venous graft ostium, successfully crossed the occlusion, was snared, externalized through the JR guide and switched to soft coronary wire using Finecross (Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) microcatheter (Fig. 3). We then finished the procedure with 3.5 × 24 BioMime DES (Meril Medical, India) implantation and distal stent angioplasty with 2.75 × 30 mm In.Pact Falcon paclitaxel-eluting balloon (Medtronic, USA) without any complications, including distal embolism (Fig. 4). Overall time of the intervention, including angiography, was 95 min and total contrast volume was 670 ml. Patient had been intubated for four more hours and there was no need for intraaortic balloon pump or inotropes neither intraoperatively nor after the intervention. Patient's fifth day echo showed no significant differences from the initial cardiac ultrasound (mild hypokinesia and normal ejection fraction with moderate diastolic dysfunction) and patient was discharged on the 12th day. After 60 days of observation he is alive and well on dual antiplatelet therapy.

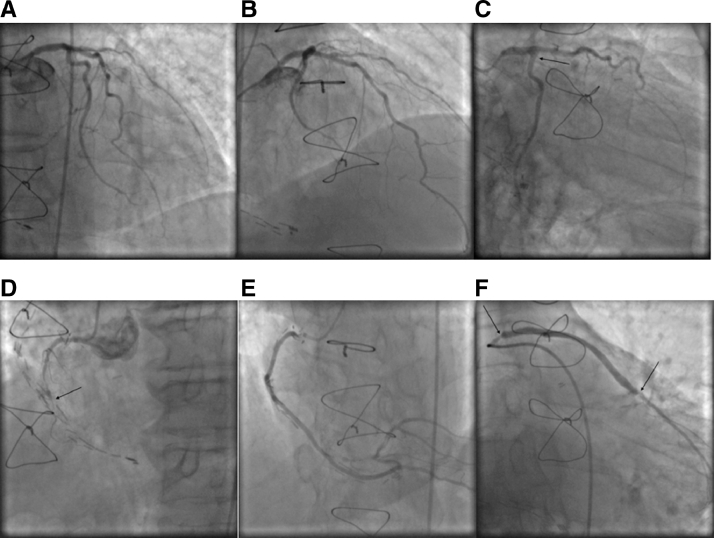

Fig. 1.

Left anterior descending artery without significant stenoses (A and B). Occluded obtuse marginal artery (arrow) (C). Occluded right coronary artery (arrow) (D). Right coronary artery venous graft (E). Obtuse marginal venous graft: note significant ostial stenosis and in stent restenosis in the previously implanted stent (arrows).

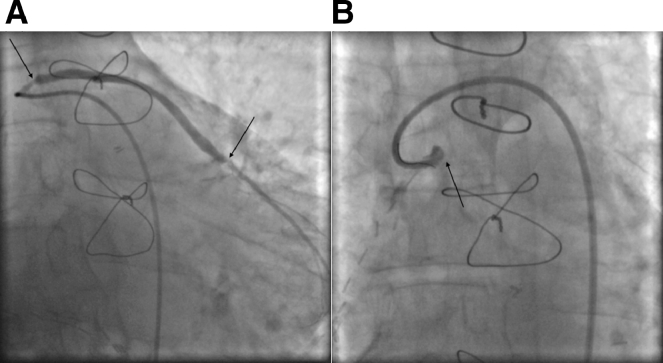

Fig. 2.

Obtuse marginal venous graft angiography pre (A) and post (B) dissection with subsequent occlusion (arrows).

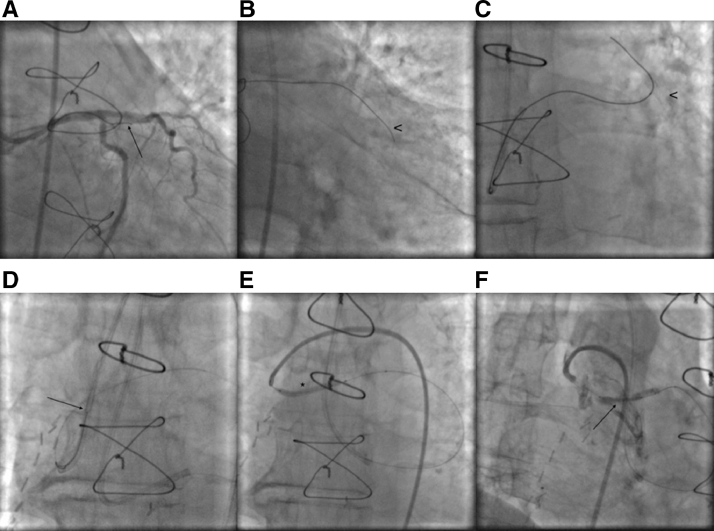

Fig. 3.

Obtuse marginal artery anterograde recanalization attempt (arrow shows the tip of the wire) (A). Obtuse marginal artery wire in the false lumen (arrowhead) (B). Retrograde true lumen passage through the stented anastomosis (arrowhead shows the stent (C). Snaring the retrograde wire (arrow shows snared wire) (D). Anterograde graft balloon angioplasty (asterisk) (E). Ostium stent positioning (arrow) (F).

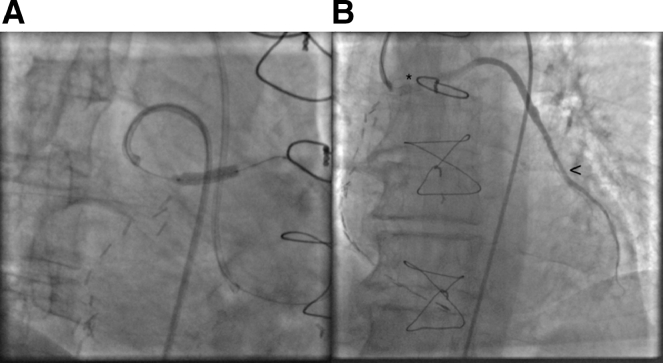

Fig. 4.

Venous graft stenting (A) and final result after in stent angioplasty (asterisk shows the stented segment and arrowhead shows anastomosis after the angioplasty) (B).

3. Discussion

Percutaneous retrograde approach has been developed for decades and it is as effective as conventional anterograde in recanalizing CTOs when it is impossible to cross anterogradely [1]. However, retrograde recanalization of the venous graft through the stented segment has never been reported to date. Garcia-Tejada et al. in an observational study showed that percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of both graft and native coronary artery were similar for immediate and midterm outcomes [2], but patients undergoing redo-CABG have a two to fourfold higher mortality than the first operation [3], [4]. Earlier in trials, it has been shown that progression from stenosis to occlusion proximally to graft anastomosis is not rare and is more common for saphenous vein grafts, so recanalizing native artery may be more difficult and even impossible in some cases [5], that is why we should keep in mind the possibility of retrograde approach for recanalizing an acute graft occlusion. In our case, the native OM artery was chronically occluded, and we were unable to gain the true lumen after multiple attempts. Due to the patient's progressively deteriorating condition and high risk of the anterograde crossing, we switched to potentially complex retrograde approach and attempted to do the maximum for percutaneous graft recanalization. If we were unable to open the occluded graft, medical management likely would have failed leading this patient to poor outcome. The only option left after failed PCI is an open surgery, but the absence of feasible venous or arterial conduits in patients with previous CABG, overall worse outcomes of open surgery in the setting of ST elevation myocardial infarction and the time needed to prepare an emergency cardiothoracic operating room makes an open surgery less preferred before attempted PCI.

This case underscores the potential complexity of diagnostic percutaneous interventions in patients with NSTEMI and history of CABG. The necessity of high skilled operators, familiar with a variety of instruments, including CTO wire and catheters is crucial in beneficial role of retrograde endovascular intervention in acute iatrogenic graft occlusions. Future work must be done to identify optimal methods of avoiding and treating this formidable complication.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript has not been previously published and not under consideration in the same of similar form in any other peer-reviewed media. All authors listed have contributed sufficiently to the project to be included as authors.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2018.04.008.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Lee C-K, Chen Y-H, Lin M-S, Yeh C-F, Hung C-S, Kao H-L, Huang C-C. Retrograde approach is as effective and safe as antegrade approach in contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusion: a Taiwan single-center registry study. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2017;33(January (1))):20–27. doi: 10.6515/ACS20160131A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia-Tejada J, Velazquez M, Hernandez F, Albarran A, Rodriguez S, Gomez I, Andreu J, Tascon J. Percutaneous revascularization of grafts versus native coronary arteries in postcoronary artery bypass graft patients. Angiology. 2009;60(February–March (1):60–66. doi: 10.1177/0003319708317335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yau TM, Borger MA, Weisel RD, Ivanov J. The changing pattern of reoperative coronary surgery: trends in 1230 consecutive reoperations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;120:156–163. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2000.106983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peduzzi P, Kamina A, Detre K. Twenty-two-year follow-up in the VA cooperative study of coronary artery bypass surgery for stable angina. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:1393–1399. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tanaka A, Ishii H, Oshima H, Shibata Y, Tatami Y, Osugi N, Ota T, Kawamura Y, Suzuki S, Usui A, Murohara T. Progression from stenosis to occlusion in the proximal native coronary artery after coronary artery bypass grafting. Heart Vessels. 2016;31(July (7):1056–1060. doi: 10.1007/s00380-015-0715-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.