Abstract

Objective

This study aims to examine factors associated with postpartum follow-up and glucose tolerance testing (GTT) in women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM).

Materials and Methods

Case-control study of women with GDM at a single institution with available outpatient records (January 2008–February 2016). Women with pregestational diabetes mellitus were excluded. The postpartum follow-up, GTT completion, and the reason for GTT completion failure (provider vs. patient noncompliance) were assessed. Bivariable and multivariable analyses were performed to identify factors associated with postpartum follow-up and GTT completion.

Results

Of 683 women, 82.0% (n ¼ 560) returned postpartum, and 49.8% (n ¼ 279) of those completed GTT. Women with Medicaid and late presentation to care were less likely to return (adjusted odds ratio [aOR]: 0.3, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.2–0.6 and aOR: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.2–0.7), but if they did, both factors were associated with increased odds of GTT completion (aOR: 2.0, 95% CI: 1.3–2.9 and aOR: 3.5, 95% CI: 1.8–6.6). Patient and provider noncompliance contributed equally to GTT completion failure. Trainee involvement was associated with improved test completion (aOR: 4.6, 95% CI: 2.4–8.8).

Conclusion

The majority of women with GDM returned postpartum, but many did not receive recommended GTT. Public insurance and late presentation were associated with failure to return postpartum, but better GTT completion when a postpartum visit occurred. Trainee involvement was associated with improved adherence to screening guidelines.

Keywords: gestational diabetes mellitus, glucose tolerance test, postpartum

The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as the onset or first recognition of carbohydrate intolerance in pregnancy,1 is rapidly rising in the United States, with a 68% increase over the last two decades.2 In addition to the increased risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes during pregnancy, GDM has substantial implications for long-term maternal health including a 13-fold increased risk of GDM in a subsequent pregnancy and 7-fold increased risk of development of diabetes mellitus later in life.3,4 Moreover, there appear to be racial and ethnic disparities in this risk, with non-Hispanic black women at greatest risk of developing diabetes after a pregnancy complicated by GDM.5 Up to one-third of affected women will have diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose metabolism during the postpartum period,6 and thus, the postpartum visit provides a critical opportunity to identify and treat persistent, abnormal glucose homeostasis.

Due to the increased risk of abnormal glucose homeostasis, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Diabetes Association recommend women with GDM undergo a 75-g, 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test (GTT) at 6 to 12 weeks’ postpartum.1 Women who screen positive for type 2 diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance are recommended further interventions for the management of hyperglycemia and prevention of complications. These important preventive strategies cannot be employed, however, if the postpartum test is not completed.

Despite these recommendations for postpartum evaluation, overall adherence with postpartum GTT is poor.7 Rates have been reported at approximately 40%, but can vary significantly with some reported rates as high as 84%.8 Many different types of barriers to postpartum diabetes testing have been identified, including patient and provider characteristics; however, no clear or consistent correlation has been established with any one factor.8,9 Women who do not return for any postpartum care are unable to undergo testing, and thus return for a postpartum visit represents the first step in prevention of disease progression and optimization of maternal health.1

Therefore, this study aims to determine what patient and provider factors are associated with receipt of indicated postpartum care after a pregnancy complicated by GDM, with a focus on identifying areas for intervention in the care of patients with GDM. Specifically, the primary objective was to assess factors associated with follow-up for a postpartum visit and the secondary objective was to assess factors associated with completion of a postpartum GTT.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective case-control study of women diagnosed with GDM who delivered at Northwestern Memorial Hospital (January 2008–February 2016) and received care in one of the four large group practices. This cohort was chosen due to the availability of centralized outpatient electronic medical record and included patients cared for by generalist and subspecialist faculty physicians as well as resident/fellow physicians with faculty supervision. Both prenatal care and management of GDM was performed primarily by the obstetric provider.

All women with a confirmed diagnosis of GDM were included in the analysis if their postpartum follow-up visit was scheduled at an eligible site. Women were excluded if they had a history of pregestational diabetes mellitus or delivered at an outside hospital. If a woman had multiple pregnancies complicated by GDM in the study period, only data for the index pregnancy were included. Women were included regardless of plurality and pregnancy outcome.

Analyses were performed both for (1) postpartum follow-up visit and (2) completion of postpartum GTT among those who followed up. First, for the primary objective, eligible women were assessed for return for a postpartum visit. Controls were defined as women who did not return for a recommended follow-up visit, and cases were defined as women who returned within 4 months of delivery. Four months was chosen to capture the majority of women who were returning for a follow-up visit related to the pregnancy while acknowledging that not all women return in the recommended 6 to 12 weeks’ time period. Next, for the secondary objective, in the subgroup of women who returned for a postpartum visit, we assessed completion of a postpartum GTT. In this nested case-control analysis, controls were defined as women who did not complete a 2-hour GTT, and cases were defined as women who completed the test. Women who did not return for postpartum care were excluded from analysis for the secondary objective.

Finally, in the subgroup of women who returned for a postpartum visit, the reason for failure to complete a GTT was assessed. These reasons were classified as provider noncompliance if a GTT was never ordered (in the electronic medical record system) by the provider and patient noncompliance if an ordered GTT was not completed by the patient.

Medical records were abstracted for sociodemographic characteristics associated with barriers to care, including maternal age, race and ethnicity, primary language, and insurance status. We assessed care characteristics including resident and fellow involvement in care and whether the patient presented to care at one of the four sites after 24 weeks’ gestation. Obstetrical history specific to GDM diagnosis was collected including method and timing of diagnosis and type of GDM management (diet-controlled vs. medication-requiring). Complications during labor and delivery which could also be associated with the likelihood of return for postpartum care including the route of delivery and whether the neonate was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit were abstracted.

Cases and controls were compared in bivariable analyses using Student’s t-test, χ2 test, and Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Factors associated with postpartum follow-up (primary objective) with p < 0.1 were retained for consideration in the multivariable logistic regression model. In the subgroup of women who returned for follow-up, analyses were performed similarly for completion of postpartum GTT (secondary objective) and in the limited subgroup analysis evaluating the reason for GTT noncompliance. Analyses were performed with Stata, Version 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). All tests were two-tailed and p < 0.05 was used to define significance. Approval for this study was obtained from the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board.

Results

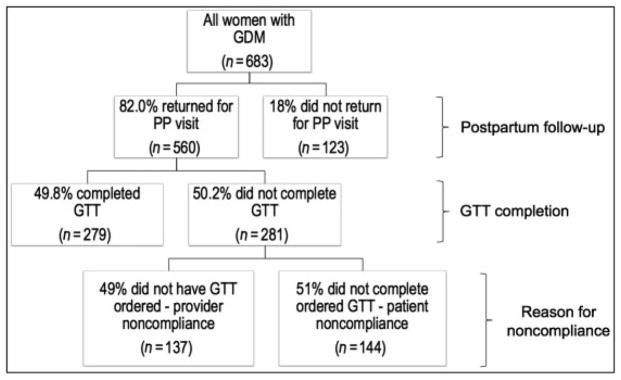

During the study period, 683 women met the eligibility criteria, and 82.0% of these (N ¼ 560) returned for a post-partum visit (Fig. 1). Of the 560 women who returned for a postpartum visit, 49.8% (N ¼ 279) completed a 2-hour GTT. Thus, 59.2% (N ¼ 404) of the total study population did not complete a postpartum screening test.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of postpartum visit attendance and glucose tolerance test completion

Women who returned for a postpartum visit were more likely to be older, married, nulliparous, nonsmokers, and non-Hispanic white or Asian. Women who returned were less likely to have Medicaid insurance, have delivered preterm, have presented late to care, or have received care in the clinic staffed by resident and fellow trainees (Table 1). There was no difference in follow-up for a postpartum visit based on living distance from the clinic. In the multivariable regression model, Medicaid insurance, late presentation to care, and preterm delivery remained independently associated with decreased odds of follow-up while Asian race was protective (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maternal demographic and clinical characteristics associated with postpartum follow-up after pregnancy complicated by GDM

| Bivariable analyses | Multivariable analyses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No postpartum follow-up n ¼ 124 |

Postpartum follow-up n ¼ 559 |

p-Value | Postpartum follow-up OR (95% CI)a | Postpartum follow-up a OR (95% CI)a | |

| Age (y) | 31.5 ± 6.9 | 33.1 ± 5.3 | <0.01 | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 28.4 ± 7.2 | 29.3 ± 7.7 | 0.27 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | – |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.01 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 24 (19.5) | 140 (25.0) | Reference | Reference | |

| Hispanic | 42 (34.2) | 139 (24.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 1.3 (0.7–2.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 37 (30.1) | 112 (20.0) | 3.00 (1.0–9.0) | 1.8 (0.8–3.8) | |

| Asian | 4 (3.3) | 70 (12.5) | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 4.2 (1.1–15.3) | |

| Other or Unknown | 16 (13.0) | 99 (17.7) | 0.6(0.3–1.0) | 1.9 (0.8–4.4) | |

| Medicaid insurance | 80 (74.1) | 187 (39.3) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.1–0.4) | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) |

| Non-English language | 10 (8.1) | 30 (5.4) | 0.24 | 0.6 (0.3–1.4) | – |

| Married | 44 (35.5) | 346 (61.9) | <0.001 | 2.9 (1.9–4.4) | 1.6 (0.9–2.8) |

| Nulliparous | 39 (31.5) | 274 (49.0) | <0.001 | 2.1 (1.4–3.1) | 1.7 (1.0–2.9) |

| Tobacco use | 8 (6.5) | 15 (2.7) | 0.04 | 0.4 (0.2–1.0) | 0.8 (0.3–2.5) |

| Resident or Fellow involvement | 91 (74.0) | 213 (38.0) | <0.001 | 0.2 (0.1–0.3) | –b |

| Late presentation to care (>24 wk) | 46 (37.1) | 86 (15.4) | <0.001 | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

| Preterm delivery (<37 wk) | 27 (21.8) | 74 (13.2) | 0.02 | 0.5 (0.3–0.9) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

| Multiple gestation | 8 (6.5) | 38 (6.8) | 0.89 | 1.1 (0.5–2.3) | – |

| GDM type A2 | 24 (19.4) | 133 (23.8) | 0.29 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | – |

| Gestational age at time of GDM diagnosis | 0.08 | ||||

| Routine 24–28 wk | 79 (64.2) | 396 (70.7) | Reference | Reference | |

| Early < 24 wk | 16 (13.0) | 83 (14.8) | 1.0 (0.6–1.9) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | |

| Late > 28 wk | 28 (22.8) | 81 (14.5) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | |

| Route of delivery | 0.10 | – | |||

| Cesarean | 38 (30.7) | 226 (40.4) | Reference | ||

| Spontaneous vaginal | 76 (61.3) | 302 (54.0) | 0.7 (0.4–1.0) | ||

| Operative vaginal | 10 (8.1) | 31 (5.6) | 0.5 (0.2–1.2) | ||

| NICU admission | 27 (22.0) | 125 (22.4) | 0.91 | 1.0 (0.6–1.6) | – |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; GDM type A2, medication controlled gestational diabetes mellitus; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Note: Bivariable analyses presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. Statistically significant values are identified in bold.

Adjusted for factors with p < 0.1: maternal age, race/ethnicity, Medicaid insurance, marital status, preterm delivery, nulliparity, late presentation to care, tobacco use, gestational age at the time of GDM diagnosis.

Not retained in the model due to collinearity with payer status.

In the subgroup of women who presented for postpartum care (n ¼ 560), women who completed a postpartum GTT were more likely to have Medicaid insurance, be non-English speaking, use tobacco, and have presented late to prenatal care. They were less likely to have been diagnosed with GDM diagnosis after 28 weeks (Table 2). However, there was no difference in GTT completion based on the timing of follow-up for the postpartum visit. On multivariable logistic regression, Medicaid insurance and late presentation to care remained independently associated with improved odds of GTT completion and diagnosis of GDM after 28 weeks with decreased odds of GTT completion (Table 2).

Table 2.

Maternal demographic and clinical characteristics associated with postpartum GTT completion among women returning for postpartum care

| Bivariable analyses | Multivariable analyses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No GTT n ¼ 281 |

GTT n ¼ 279 |

p-Value | GTT OR(95% CI) | GTT aOR (95% CI)a | |

| Age (y) | 33.2 ± 5.1 | 33.1 ± 5.5 | 0.79 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | – |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 33.4 ± 7.3 | 34.0 ± 7.4 | 0.39 | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | – |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.23 | – | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 80 (28.5) | 60 (21.5) | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 69 (24.6) | 70 (25.1) | 1.4 (0.9–2.4) | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 54 (19.2) | 58 (20.8) | 2.1 (1.2–3.8) | ||

| Asian | 27 (9.6) | 43 (15.4) | 1.8 (0.6–2.3) | ||

| Other or unknown | 51 (18.2) | 48 (17.2) | 1.4 (0.8–2.2) | ||

| Medicaid insurance | 67 (28.8) | 121 (49.6) | <0.001 | 2.4 (1.7–3.6) | 2.0 (1.3–2.9) |

| Non-English language | 10 (3.6) | 20 (7.2) | 0.06 | 2.1 (1.0–4.6) | 1.4 (0.5–3.6) |

| Married | 181 (64.4) | 165 (59.1) | 0.20 | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | – |

| Nulliparous | 136 (48.4) | 138 (49.5) | 0.80 | 1.0 (0.8–1.5) | – |

| Tobacco use | 8 (2.9) | 7 (2.5) | 0.06 | 0.9 (0.3–2.5) | 0.7 (0.2–2.1) |

| Resident or Fellow involvement | 75 (26.7) | 138 (49.5) | <0.001 | 2.7 (1.9–3.8) | –b |

| Late presentation to care (> 24 wk) | 25 (8.9) | 61 (21.9) | <0.001 | 2.9 (1.7–4.7) | 3.5 (1.8–6.6) |

| Preterm delivery (<37 wk) | 42 (14.9) | 32 (11.5) | 0.22 | 0.7 (0.5–1.2) | – |

| Multiple gestation | 18 (6.4) | 20 (7.2) | 0.72 | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | – |

| GDM type A2 | 59 (21.0) | 74 (26.5) | 0.12 | 1.4 (0.9–2.0) | – |

| Gestational age at time of GDM diagnosis | 0.005 | ||||

| Routine 24–28 wk | 194 (69.0) | 202 (72.4) | Reference | Reference | |

| Early < 24 wk | 34 (12.1) | 49 (17.6) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | |

| Late > 28 wk | 53 (18.9) | 28 (10.0) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) | |

| Route of delivery | 0.83 | – | |||

| Cesarean | 113 (40.2) | 113 (40.5) | Reference | ||

| Spontaneous vaginal | 154 (54.8) | 149 (53.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | ||

| Operative vaginal | 14 (5.0) | 17 (6.1) | 1.2 (0.6–2.6) | ||

| NICU admission | 67 (23.9) | 58 (20.8) | 0.37 | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) | – |

Abbreviations: aOR, adjusted odds ratio; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; GDM type A2, medication controlled gestational diabetes mellitus; GTT, glucose tolerance test; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit.

Note: Bivariable analyses presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. Statistically significant values are identified in bold.

Adjusted for factors with p < 0.1: Medicaid insurance, non-English language, transfer/late presentation to care, tobacco use, gestational age at the time of GDM diagnosis.

Not retained in the model due to collinearity with payer status.

Nearly half (48.9%) of GTT noncompletion was due to provider noncompliance, and the remainder (51.1%) was due to patient noncompliance. The involvement of residents and fellows in patient care was associated with improved GTT completion as it significantly increased the frequency of a GTT being ordered (90.6% provider compliance among resident/fellows versus 65.4% provider compliance among non-trainees, p < 0.001). This association remained significant (adjusted odds ratio: 4.6, 95% confidence interval: 2.4–8.8) after controlling for confounders found to be significant in the bivariable analysis: maternal age, body mass index, race, marital status, late presentation, GDM type, and timing of GDM diagnosis. Payer status was not retained in the model due to collinearity with resident and fellow involvement. No other factors aside from trainee involvement were associated with odds of GTT being ordered.

Comment

Postpartum care for women with GDM represents a critical window of opportunity to screen for abnormal glucose homeostasis, counsel about lifestyle changes to reduce the risk of overt diabetes, and provide a smooth transition to long-term preventive health care. Despite the established importance of postpartum screening,10 GTT completion rates remain suboptimal.8 In this study, the majority (82.0%) of women with GDM returned postpartum, but over half (59.2%) did not receive the recommended GTT.

Although this low rate of adherence was due in part to lack of presentation for the postpartum visit, it was primarily due to inconsistent completion of a GTT after presenting to care. We identified multiple patients and provider characteristics associated with lack of follow-up and GTT noncompliance and demonstrated that barriers to follow-up for a postpartum visit and barriers to GTT completion were not always the same. For example, public insurance and late presentation to care were associated with decreased odds of return for a postpartum visit, but improved odds of GTT completion if the patient did return.

Prior studies have similarly demonstrated poor compliance with recommended postpartum screening after a pregnancy complicated by GDM. Our finding of a 40.8% GTT completion rate is comparable to published rates of 40 to 50%,8,11–13 suggesting this is an appropriate population to study to determine barriers to optimal care. A commonly cited reason for poor adherence to postpartum screening guidelines is the lack of return for a postpartum visit,8,9,11 which is not unique to women with GDM.14 After implementation of a program targeted at improving postpartum follow-up specifically for women with GDM, one Australian study noted an improvement in screening rate from 43.7 to 84.4%,15 suggesting this could be a potential area for intervention. We identified multiple disparities in our population associated with lack of postpartum follow-up, including public insurance and late presentation to care. These findings have not been demonstrated previously, possibly due to small sample size and inadequate power to detect a significant difference,6,16 but they suggest that these populations are important to target when designing interventions to improve postpartum follow-up.

Even when the patient successfully returns for a postpartum visit, additional factors contribute to the suboptimal completion of the postpartum GTT. In the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study, older age, a higher level of education, earlier GDM diagnosis, and medication requirement during pregnancy were associated with completion of postpartum diabetes testing.11 Ferrara et al hypothesized these factors were associated with improved testing rates due to a heightened awareness of the GDM diagnosis and its potential long-term complications. Similarly, Dietz et al demonstrated that initiation of prenatal care in the first trimester, a sign of patient commitment to her own health care, is predictive of postpartum testing.9 Our results support these studies as we demonstrate women who were diagnosed with

GDM after 28 weeks were less likely to be adherent to the postpartum GTT. It is critical, however, to make the distinction between late diagnosis of GDM, due to noncompliance with prenatal care recommendations, and late presentation to care, due to barriers to accessing care. In contrast to the above findings, we found that women who presented late to care were less likely to return for a postpartum visit, but more likely to complete the postpartum GTT if they returned. Our results likely differ from prior work because our study design distinguished postpartum follow-up from postpartum GTT completion.12 Furthermore, these results demonstrate the need to evaluate barriers to care at different points in the sequence of events preceding the postpartum screening test.

Compliance with postpartum testing was also influenced by provider factors. Among women who did not complete a GTT, over half never had an order placed by their obstetric provider. Provider noncompliance has been demonstrated in multiple other studies and is thought to result from lack of communication between providers, lack of familiarity with testing guidelines, and variation in practice sites.9,17 Providers may assume that screening will be performed by a primary care provider, although our findings did not suggest that women were receiving a GTT ordered by other physicians in our health care system. We found that the involvement of obstetrics and gynecology residents or maternal-fetal medicine fellows, who might be more up to date on current recommendations, was associated with improved provider adherence to GTT screening guidelines. This finding highlights the importance of ongoing education and reminders to providers of all levels regarding the benefits of screening during the postpartum encounter. The optimal method of improving provider compliance, however, remains uncertain. Automated reminders were previously not found to be beneficial,13 but perhaps reflex bundles linking diagnoses to automated test orders or other multilevel interventions may be more successful.7

Strengths of our study include the unique study design, which enabled us to separately evaluate factors associated with postpartum follow-up and factors associated with postpartum GTT completion. Some patient characteristics noted to be associated with failure to follow-up were, in contrast, associated with higher likelihood of postpartum GTT completion when a postpartum visit occurred, highlighting the importance of studying barriers at each level in the cascade of care. Moreover, our study setting allowed us to evaluate a diverse patient and provider population, shedding light on possible areas for intervention, such as the role of trainee providers. However, there are several limitations to note. While the study design allowed us to evaluate factors predictive of postpartum follow-up and screening separately, our power to detect a significant difference was diminished in subgroup analyses. Although we adjusted for all significant differences between groups in multivariable analyses, we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured confounding. Additionally, the study population was drawn from a tertiary medical center where some patients may have transferred in for care and may have followed up with their referring provider for postpartum care. Similarly, we were unable to study women who received antenatal care at this institution but did not deliver at this hospital, as we do not have information about the timing or location of outside deliveries or whether such deliveries were intentionally at another hospital. Furthermore, due to the nature of care at this institution where most outpatients seen by residents and fellows have publicly funded prenatal care, we cannot use statistical methods to distinguish the relationship between trainee involvement and Medicaid insurance fully.

The barriers to postpartum follow-up and GTT completion following a pregnancy complicated by GDM are multi-faceted. We must continue to direct attention at each level of the postpartum cascade of care, from appointment attendance to provider role to patient adherence, to optimize care for this important and growing population. There is potential for improvement in identifying and overcoming patient-specific barriers to increase the rate of return for a postpartum visit. Moreover, there is potential for improvement in provider training and awareness to increase the rate of provider compliance with recommended screening guidelines. Further evaluation of these issues within different patient populations and health care systems are needed to determine what interventions will be most effective in optimizing postpartum identification of abnormal glucose homeostasis.

Condensation

A large proportion of women with gestational diabetes mellitus do not receive recommended postpartum care due to both patient and provider noncompliance.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant Number UL1TR001422, via the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute Enterprise Data Warehouse Pilot program. Additionally, Lynn M. Yee is supported by the NICHD K12 HD050121–11. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Note

This study was presented in the poster format at the 37th annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine; January 23–28, 2017; Las Vegas, NV.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No 137: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 Pt 1):406–416. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000433006.09219.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrara A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl 2):S141–S146. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boghossian NS, Yeung E, Albert PS, et al. Changes in diabetes status between pregnancies and impact on subsequent newborn outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210(05):431.e1–431.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9677):1773–1779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60731-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang AH, Li BH, Black MH, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in diabetes risk after gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2011;54(12):3016–3021. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2330-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell MA, Phipps MG, Olson CL, Welch HG, Carpenter MW. Rates of postpartum glucose testing after gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(06):1456–1462. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000245446.85868.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez NG, Niznik CM, Yee LM. Optimizing postpartum care for the patient with gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(03):314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen KK, Kapur A, Damm P, de Courten M, Bygbjerg IC. From screening to postpartum follow-up - the determinants and barriers for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) services, a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:41–58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dietz PM, Vesco KK, Callaghan WM, et al. Postpartum screening for diabetes after a gestational diabetes mellitus-affected pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(04):868–874. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318184db63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice; Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. Committee Opinion No 666: Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(06):e187–e192. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrara A, Peng T, Kim C. Trends in postpartum diabetes screening and subsequent diabetes and impaired fasting glucose among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus: A report from the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(02):269–274. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho GJ, An J-J, Choi S-J, et al. Postpartum glucose testing rates following gestational diabetes mellitus and factors affecting non-compliance from four tertiary centers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30(12):1841–1846. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.12.1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zera CA, Bates DW, Stuebe AM, Ecker JL, Seely EW. Diabetes screening reminder for women with prior gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(01):109–114. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rankin KM, Haider S, Caskey R, Chakraborty A, Roesch P, Handler A. Healthcare utilization in the postpartum period among Illinois women with Medicaid paid claims for delivery, 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(Suppl 1):144–153. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beischer NA, Wein P, Sheedy MT. A follow-up program for women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Med J Aust. 1997;166(07):353–357. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb123162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smirnakis KV, Chasan-Taber L, Wolf M, Markenson G, Ecker JL, Thadhani R. Postpartum diabetes screening in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(06):1297–1303. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000189081.46925.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuebe A, Ecker J, Bates DW, Zera C, Bentley-Lewis R, Seely E. Barriers to follow-up for women with a history of gestational diabetes. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27(09):705–710. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1253102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]