Abstract

Background

UK Biobank is a well-characterised cohort of over 500 000 participants that offers unique opportunities to investigate multiple diseases and risk factors.

Aims

An online mental health questionnaire completed by UK Biobank participants was expected to expand the potential for research into mental disorders.

Method

An expert working group designed the questionnaire, using established measures where possible, and consulting with a patient group regarding acceptability. Case definitions were defined using operational criteria for lifetime depression, mania, anxiety disorder, psychotic-like experiences and self-harm, as well as current post-traumatic stress and alcohol use disorders.

Results

157 366 completed online questionnaires were available by August 2017. Comparison of self-reported diagnosed mental disorder with a contemporary study shows a similar prevalence, despite respondents being of higher average socioeconomic status than the general population across a range of indicators. Thirty-five per cent (55 750) of participants had at least one defined syndrome, of which lifetime depression was the most common at 24% (37 434). There was extensive comorbidity among the syndromes. Mental disorders were associated with high neuroticism score, adverse life events and long-term illness; addiction and bipolar affective disorder in particular were associated with measures of deprivation.

Conclusions

The questionnaire represents a very large mental health survey in itself, and the results presented here show high face validity, although caution is needed owing to selection bias. Built into UK Biobank, these data intersect with other health data to offer unparalleled potential for crosscutting biomedical research involving mental health.

Declaration of interest

G.B. received grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the study; and support from Illumina Ltd. and the European Commission outside the submitted work. B.C. received grants from the Scottish Executive Chief Scientist Office and from The Dr Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation during the study. C.S. received grants from the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust during the study, and is the Chief Scientist for UK Biobank. M.H. received grants from the Innovative Medicines Initiative via the RADAR-CNS programme and personal fees as an expert witness outside the submitted work.

UK Biobank is a very large, population-based cohort study established to identify the determinants of common life-threatening and disabling conditions. 1 Most of these conditions, such as heart disease, stroke and mental disorders, are multifactorial, involving multiple genes of small effect and complex relationships with environmental exposures. This means that large samples are required to study associations between these exposures and disease, and to identify targets for treatment and prevention. 2 The utility of traditional epidemiological study designs is often limited by their focus on single disorders or exposures and their relatively modest sample sizes. 3 UK Biobank is an open-access resource providing detailed characterisation of over half a million people aged 40–69 years at recruitment, with proposed long-term follow-up. Recruitment was completed in 2010, and consent was obtained for future contact and linkage to routinely collected health-related data, such as those produced by the National Health Service (NHS). Baseline measures were extensive, from family history to sensory acuity (a searchable breakdown can be found at www.ukbiobank.ac.uk), and the resource continues to grow. Genotyping of the whole cohort was completed earlier this year, blood biomarkers are due next year, and multimodal imaging is underway for 100 000 participants. Information on local environmental factors, such as air pollution, is also available. The design of UK Biobank offers the opportunity to examine a wide range of risk factors and outcomes in a sample large enough to provide the power to detect small effects, making UK Biobank a highly efficient resource for observational epidemiology.

The effect of mental disorders on disability and quality of life is considerable, 4 accounting for the equivalent of over 1.2 million person years lost to disability from mental and substance use disorders in England alone in 2013. 5 Recent work has also highlighted the potential detrimental effect of mental disorders on both onset and outcome of physical disease. 6 – 8 Having mental health phenotypes available, in conjunction with the wealth of other data in the UK Biobank, would offer considerable opportunities to study aetiological and prognostic factors. The UK Biobank baseline data collection involved limited assessment of mental health, consisting of several questions about mood and a neuroticism scale, expanded for the past 172 729 recruited participants with questions to allow provisional categorisation of mood disorder; 9 however, there was considerable scope for further characterisation of mental disorders among participants.

Outcome ascertainment

Characterising mental disorders in a cohort such as UK Biobank poses several challenges. First, most mental disorders manifest before 30 years of age and have fluctuating courses, 10 so a ‘snapshot’ of disorder status at one point in time, as identified by most screening tools, is likely to be less useful than a lifetime history. Second, traditional diagnostic approaches to mental disorders, relying upon clinician assessment at interview, would be prohibitively expensive in a cohort of this size. Third, using self-report of diagnosis or data from record linkages relies upon recognition of illness and reflects healthcare usage patterns, whereas many people with mental disorders never seek or receive treatment. 10 , 11 In response to these challenges, we developed a dual approach: secondary care record linkage for identification of more severe illnesses such as schizophrenia, 12 and self-report of symptoms of common mental disorders, which might not have come to clinical attention. As part of our mental health phenotyping programme, we therefore developed an online mental health questionnaire (MHQ) for participants to complete regarding lifetime symptoms of mental disorders. The MHQ aimed to exploit the efficiency of ‘e-surveys’ 13 and provide enough detail to identify mental health disorders without the need for a clinical assessment.

The present paper aims to describe the development, implementation and results of this questionnaire. We provide descriptive data on the numbers of UK Biobank participants meeting diagnostic criteria for specific disorders, and on the frequency of exposure to risk factors. We also evaluate the likely representativeness of respondents by comparing respondent sociodemographic characteristics to those of the UK population using census data, and by comparing self-reported mental disorder diagnosis with the Health Survey for England (HSE) data. 14 This will assist researchers considering or undertaking epidemiological research to evaluate the potential and power of using UK Biobank to look at mental health.

Method

Questionnaire development

A mental health research reference group formed of approximately 50 individuals (see Supplementary Appendix 1, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.12) participated in discussions about a strategy for mental health phenotyping in UK Biobank, including a workshop in January 2015. From this, a smaller steering group was established and led the development of the MHQ. The group recommended that the MHQ should concentrate on depression, as it was likely to represent the greatest burden in the cohort, with some questions about other common disorders, including anxiety, alcohol misuse and addiction, plus risk factors for mental disorder not captured at participants' baseline assessment.

The intention was to create a composite questionnaire from previously existing and validated measures, taking into account participant acceptability (time, ease of use and ensuring questions were unlikely to offend), scope for collaborations with international studies (e.g. the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium) through making results comparable, and the need to balance depth and breadth of phenotyping. The basis of the questionnaire was the measurement of lifetime depressive disorder using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF), 15 modified to provide lifetime history, as used to identify cases and controls for some existing studies in the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. The CIDI-SF uses a branching structure with screening questions and skip-rules to limit detailed questions to the relevant areas for each participant. Other measures were then added to this, as summarised in Supplementary Table SM1. Where the group were unable to find existing measures that fulfilled these criteria, questions were written or adapted, as indicated in SM1. These sections have not been externally validated, but the questions can be seen, along with the full questionnaire, on the UK Biobank website (http://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/refer.cgi?id=22) for researchers to evaluate how they wish to use them.

Testing and ethical approval

The use of branching questions in the MHQ means that those with established and multiple mental disorders have a longer, more detailed, questionnaire. To improve acceptability in this group, we worked with a patient advisory group at the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at the South London and Maudsley (SLaM) NHS Foundation Trust in designing the questionnaire and invitation. 16 We then piloted the questionnaire among an online cohort of 14 836 volunteers aged over 50 and living in the UK, who completed the questionnaire as part of signing up to take part in the Platform for Research Online to investigate Genetics and Cognition in Ageing (PROTECT). 17 Of those who started the questionnaire, 98.8% completed it, taking a median time of 15 min. Some PROTECT participants commented that they wanted the opportunity to explain why they felt they had experienced symptoms of depression. In response to this, we added a question to the depression section on loss or bereavement, and a free-text box – neither were designed to change diagnostic algorithms, but may add to future analyses.

The questionnaire was approved as a substantial amendment to UK Biobank by the North West – Haydock Research Ethics Committee, 11/NW/0382.

Administration to UK Biobank participants

We incorporated the final MHQ into the UK Biobank web questionnaire platform and presented it to participants as an online questionnaire entitled ‘thoughts and feelings’. We sent participants who had agreed to email contact a hyperlink to their personalised questionnaire. The invitation explained the importance of collecting further information about mental health and emphasised that UK Biobank was unable to respond to concerns raised by the participant in the questionnaire, instead directing them to several sources of potential support. Participants could skip questions they preferred not to answer, and they could save answers to return to the questionnaire later. We sent reminder emails at 2 weeks and 4 months to those who had not started or had partially completed the questionnaire. The MHQ will continue to be available on the participant area of the UK Biobank website, and the annual postal newsletter contains an invitation to log on to the participant area and complete the MHQ, to reach those for whom no email contact was possible. Data from this questionnaire will therefore continue to accrue. The current numbers and aggregate data can be accessed from the public data showcase (http://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/label.cgi?id=136). More detail on the roll out and associated communications can be found on the UK Biobank website (http://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/refer.cgi?id=22).

Defining cases from the MHQ

Case definitions for the evaluation of the responses to the MHQ are detailed in Supplementary Appendix 2. They arose either from the instruments used in the MHQ or by consensus criteria agreed by the working committee who wrote the MHQ. Diagnostic criteria were evaluated for depression (major depressive disorder), hypomania or mania, generalised anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Addiction to substances and/or behaviour was defined based on self-report alone. Unusual experiences (describing potential symptoms of psychosis) and self-harm were also defined as phenomena that are important for phenotyping, but not disorder specific. We combined outcomes to divide the cohort into five mood disorder groups, as shown in Supplementary Figure MD1.

Fulfilling the diagnostic criteria based on a self-report questionnaire did not allow us to rule out other psychiatric disorders, or psychological or situational factors that might better explain the symptoms and may have been elicited in a clinical evaluation. Therefore, we regarded any case classification arising from the MHQ as ‘likely’ rather than confirmed psychiatric disorder. The issue becomes particularly problematic for disorders that are less common in the population, such as bipolar affective disorder, where the literature shows that using questionnaires to screen the population may over-estimate prevalence. 18 Therefore, although we reported the presence of hypomania/mania symptoms for the whole population, we only made the likely diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder in people with a history of depression, a sub-population where the prevalence of bipolar affective disorder is higher, and therefore screening questionnaires have better positive predictive values. 19

Analysis and data sharing

Data were supplied by UK Biobank on 8th August 2017 under application number 16577. We used R version 3.4.0 and MS Excel for analyses. We reported numbers and proportions within the sample and did not attempt to give population prevalence estimates. The large sample size meant that all 95% confidence intervals were less than 0.3 away from percentage proportions and are therefore not shown.

The data for tables can be found in online Supplementary materials. The code is available from Mendeley Data (http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/kv677c2th4.1). Raw data are available from UK Biobank subject to the usual access procedures (www.ukbiobank.ac.uk).

Role of the funding source

The questionnaire was developed and administered with UK Biobank funding. Individual authors were funded by their institutions and research grants as detailed below. No funding body influenced the study design or the writing of this article. M.H. had access to all data through a standard data sharing agreement (Material Transfer Agreement) with UK Biobank and had final responsibility for the decision to submit the article for publication.

Results

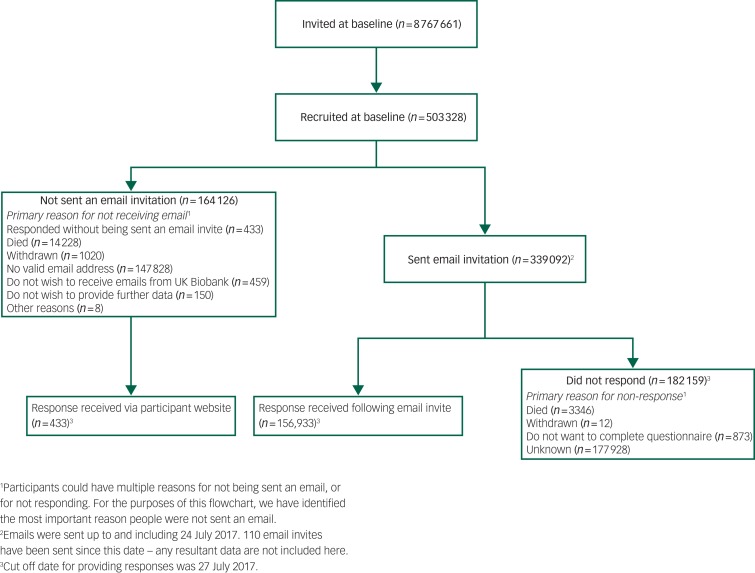

The setting, recruitment and methods of selection of participants in UK Biobank have been published elsewhere. 1 , 9 For the MHQ study, 339 092 participants were sent an email invitation, and 157 366 (46% of those emailed) fully completed the questionnaire by August 2017 – which means that the MHQ currently has 31% coverage of the UK Biobank cohort. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the UK Biobank participants who completed the MHQ. The median time for completion was 14 min, and 82% of respondents completed the questionnaire in under 25 min.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of UK Biobank participants from invitation to completion of mental health questionnaire. Invitations were based on NHS registration, age and location. Numbers correct for July 2017.

Supplementary Table SM2 shows participant characteristics for all UK Biobank participants and those who completed the MHQ, compared with population-level data for UK residents in the same age range. Participants were different from the whole UK Biobank cohort and the general population in that they were better educated (e.g. 45% held a degree v. 32% of UK Biobank participants v. 23% in the census), of higher socioeconomic status according to job type, and healthier (longstanding illness or disability 28% v. 32% v. 37%), with lower rates of current smoking.

As shown in Table 1, 34% of respondents reported they had received at least one psychiatric diagnosis from a professional at some time, and 12% had received two or more. The most commonly reported diagnosis was depression, followed by ‘anxiety or nerves’. Data were compared with the HSE, because this annual survey aims to report data that is a representative estimate for the population in England through its sample and weighting. 20 The comparison shows that the pattern and prevalence of diagnosis is similar; for example, a depression diagnosis was self-reported by 21% of individuals in both samples, eating disorders by around 1%, and bipolar-related disorders by around 0.5%. The definition in the MHQ differed from that in the HSE for anxiety (MHQ definition was broader) and addiction (MHQ did not require professional diagnosis), and the higher overall prevalence in the UK Biobank MHQ compared with the HSE (35% v. 28%) may be due to those wider definitions.

Table 1.

Self-reported previous physician diagnosis a (self-reported without physician diagnosis for addiction b )

| UK Biobank MHQ responses (age 45–82 years) | Health Survey for England (HSE) (age 45–84 years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 157 366 | % in sample | N = 3272 | Prevalence (95% CI) | |

| All psychotic disorders | 723 | 0.5 | 11 | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) |

| Schizophrenia | 157 | 0.1 | NA | |

| Any other type of psychosis or psychotic illness | 604 | 0.4 | NA | |

| Depression | 33424 | 21.2 | 679 | 20.8 (19.4–22.2) |

| Mania, hypomania, bipolar or manic-depression | 837 | 0.5 | 13 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

| Anxiety, nerves or generalised anxiety disorder c | 22036 | 14.0 | 170 | 5.2 (4.5–6) |

| Panic attacks | 8704 | 5.5 | 262 | 8.0 (7.1–9.0) |

| Agoraphobia | 599 | 0.4 | NA | |

| Social anxiety or social phobia | 1962 | 1.2 | NA | |

| Any other phobia (e.g. disabling fear of heights or spiders) | 2153 | 1.4 | 27 | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 982 | 0.6 | 11 | 0.3 (0.2–0.6) |

| Any personality disorder | 385 | 0.2 | 13 | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) |

| All eating disorders | 1851 | 1.2 | 26 | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) |

| Anorexia nervosa | 891 | 0.6 | NA | |

| Bulimia nervosa | 503 | 0.3 | NA | |

| Psychological over-eating or binge-eating | 707 | 0.4 | NA | |

| Autism, Asperger's or autistic spectrum disorder | 223 | 0.1 | NA | |

| Attention-deficit or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder | 133 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.1 (0–0.3) |

| Any addiction or dependence | 9386 | 6.0 | NA | |

| Alcohol or drug addiction b | 5002 | 3.2 | 30 | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) |

| Physical alcohol dependence | 946 | 0.6 | NA | |

| Summary | ||||

| None of above | 103346 | 65.7 | 2356 | 72.0 (70.4–73.5) |

| One or more of the above | 54020 | 34.3 | 916 | 28.0 (26.5–29.6) |

| Two or more of the above | 19400 | 12.3 | NA | |

NA, not reported.

UK Biobank participants were asked: ‘Have you been diagnosed with one or more of the following mental health problems by a professional, even if you don't have it currently? (tick all that apply): By professional we mean: any doctor, nurse or person with specialist training (such as a psychologist or therapist). Please include disorders even if you did not need treatment for them or if you did not agree with the diagnosis’. HSE participants were asked to identify all the mental health conditions they had experienced, then asked whether they had been told by a doctor, psychiatrist or professional that they had it.

UK Biobank participants were asked: ‘Have you been addicted to or dependent on one or more things, including substances (not cigarettes/coffee) or behaviours (such as gambling)?’ HSE definition of addiction includes physician diagnosis.

HSE participants were asked about generalised anxiety disorder, and not about anxiety and nerves more generically.

As shown in Table 2, 35% of participants met criteria for one or more operationally defined syndromes. The most common was lifetime depression at 24%, followed by anxiety disorder and alcohol use disorder (both 7%), PTSD (6%), unusual experiences (5%) and self-harm (4%). Hypomania/mania was the least common, for 2% of respondents. As shown in Supplementary Table SM3, women were more likely than men to have a history of one or more of the defined syndromes (39% v. 30%), particularly depression, anxiety or PTSD. Men were more likely than women to have an alcohol use disorder (10% v. 5%), and there was little difference in the rate of report of unusual experiences (both 5%). Table 2 also shows the substantial comorbidity of defined syndromes. Notably, around three-quarters of participants who met criteria for lifetime anxiety disorder also met criteria for lifetime depression, while individuals with PTSD had at least a two-fold increase in lifetime prevalence of all other syndromes. Alcohol use disorder appeared less related to the others.

Table 2.

Comorbidity between operationally defined syndromes

| Overall Prevalence | Comorbidity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | Hypomania/mania | Anxiety disorder | Unusual experiences | Self-harm | Alcohol use disorder | PTSD | |||

| Total= | 55570 (35%) | 37434 (24%) | 2396 (2%) | 11111 (7%) | 7803 (5%) | 6872 (4%) | 10911 (7%) | 10064 (6%) | |

| Lifetime history | Depression a | 37434 (24%) | 1550 (4%) | 8444 (23%) | 3649 (10%) | 4240 (11%) | 3405 (9%) | 6373 (17%) | |

| Hypomania/mania b | 2396 (2%) | 1550 (65%) | 778 (32%) | 598 (25%) | 453 (19%) | 327 (14%) | 657 (27%) | ||

| Anxiety disorder (GAD) c | 11111 (7%) | 8444 (76%) | 778 (7%) | 1551 (14%) | 1704 (15%) | 1286 (12%) | 3274 (29%) | ||

| Unusual experiences d | 7803 (5%) | 3649 (47%) | 598 (8%) | 1551 (20%) | 1225 (16%) | 768 (10%) | 1594 (20%) | ||

| Self-harm e | 6872 (4%) | 4240 (62%) | 453 (7%) | 1704 (25%) | 1225 (18%) | 959 (14%) | 1719 (25%) | ||

| Current | Alcohol use disorder f | 10911 (7%) | 3405 (31%) | 327 (3%) | 1286 (12%) | 768 (7%) | 959 (9%) | 1360 (12%) | |

| PTSD g | 10064 (6%) | 6373 (63%) | 657 (7%) | 3274 (33%) | 1594 (16%) | 1719 (17%) | 1360 (14%) | ||

Percentages refer to the proportion of participants with the row syndrome who also have column syndrome. See lettered table notes, and Supplementary Appendix 2 for case definitions. GAD, generalised anxiety disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Criteria met for major depressive disorder on CIDI-SF lifetime.

Criteria met for hypomania/mania lasting for at least one week.

Criteria met for generalised anxiety disorder on CIDI-SF lifetime.

Reported potential hallucination or delusion at any point in their life.

Reported deliberate self-harm at some point in their life, asked to report self-harm ‘whether or not you meant to end your life’.

Criteria met for moderate alcohol use disorder on AUDIT during the past year.

Criteria met for post-traumatic stress disorder on PCL-6 in the past month.

The proportion of respondents meeting criteria for the lifetime occurrence of at least one of depression, anxiety, unusual experiences and addiction varied according to age and gender (Fig. 2), from 16% in men over 75 years old to 42% in women aged 45–54 years. Respondents with any of these lifetime syndromes were more likely than those without to live in areas of higher deprivation, especially if they had bipolar disorder or reported addiction (Table 3). They were also more likely to have had adverse life events and to have met criteria for loneliness and, to a lesser extent, social isolation. They were more likely to have smoked cigarettes and/or used cannabis, and to have had a ‘longstanding illness’ at baseline (although the presence of a mental disorder may have been the illness to which the participants referred in some cases). Achieving recommended levels of physical activity did not appear to be associated with any of the syndromes.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of respondents positive for one or more of depression (and bipolar disorder), generalised anxiety disorder, unusual experiences and addiction according to lifetime diagnostic criteria. By age and gender.

Table 3.

Socioeconomic factors by status for lifetime occurrence (people may be included in more than one category)

| No ‘lifetime’ criteria met a N = 102 901 | Depression b N = 37 434 | Bipolar type 1 c N = 931 | Anxiety disorder (GAD) b N = 11 111 | Unusual experiences d N = 7803 | Addiction e N = 9386 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristics | |||||||

| Age f | 45–54 | 14364 (13%) | 7145 (19%) | 228 (24%) | 2348 (21%) | 1485 (19%) | 2013 (21%) |

| 55–64 | 33307 (31%) | 14809 (40%) | 417 (45%) | 4470 (40%) | 2904 (37%) | 3428 (37%) | |

| 65–74 | 51705 (48%) | 13739 (37%) | 261 (28%) | 3892 (35%) | 2960 (38%) | 3466 (37%) | |

| 75+ (oldest is 82) | 9376 (9%) | 1741 (5%) | 25 (3%) | 401 (4%) | 454 (6%) | 479 (5%) | |

| Gender | Female | 57556 (53%) | 25815 (69%) | 532 (57%) | 7404 (67%) | 4718 (60%) | 4556 (49%) |

| Ethnicity | White | 105072 (97%) | 36297 (97%) | 892 (96%) | 10749 (97%)c | 7503 (96%) | 9037 (96%) |

| Townsend Deprivation Score g | Most deprived (TDS ≥ +2) | 11783 (11%) | 5656 (15%) | 201 (22%) | 1856 (17%) | 1426 (18%) | 1941 (21%) |

| Highest qualification | Degree | 48700 (45%) | 16939 (45%) | 425 (46%) | 5071 (46%) | 3646 (47%) | 4531 (48%) |

| Housing tenure | Rent h | 4162 (4%) | 2906 (8%) | 155 (17%) | 1026 (9%) | 854 (11%) | 1109 (12%) |

| Known risk factors | |||||||

| Neuroticism score i | Mean (s.d.) | 3.2 (2.8) | 5.6 (3.3) | 3.8 (3.1) | 7.1 (3.3) | 5.2 (3.5) | 5.4 (3.5) |

| Adverse life experiences | Childhood screen j | 43913 (40%) | 21144 (56%) | 638 (69%) | 6931 (62%) | 4783 (61%) | 5800 (62%) |

| Adult screen k | 50226 (46%) | 23893 (64%) | 685 (74%) | 7581 (68%) | 4783 (61%) | 6303 (67%) | |

| Trauma exposure l | 50771 (47%) | 22166 (59%) | 665 (71%) | 6877 (62%) | 5439 (70%) | 6278 (67%) | |

| Social connection | Loneliness i , m | 2976 (3%) | 2367 (6%) | 94 (10%) | 971 (9%) | 570 (7%) | 669 (7%) |

| Social isolation i | 7793 (7%) | 3623 (10%) | 126 (14%) | 1173 (11%) | 931 (12%) | 1200 (13%) | |

| Illness | Longstanding illness, disability or infirmity i | 26341 (24%) | 13363 (36%) | 503 (54%) | 4581 (41%) | 3242 (42%) | 3588 (38%) |

| Health-related behaviours | |||||||

| Smoking status i | Current | 6235 (6%) | 3638 (10%) | 158 (17%) | 1194 (11%) | 837 (11%) | 1916 (20%) |

| Former | 36425 (33%) | 13927 (37%) | 323 (35%) | 4009 (36%) | 2943 (38%) | 4893 (52%) | |

| Never | 65827 (61%) | 19786 (53%) | 448 (48%) | 5883 (53%) | 4003 (51%) | 2547 (27%) | |

| Cannabis use (lifetime) | Daily | 868 (1%) | 914 (2%) | 63 (7%) | 346 (3%) | 258 (3%) | 867 (9%) |

| Ever, but not daily | 19675 (18%) | 9607 (26%) | 299 (32%) | 2818 (25%) | 2312 (30%) | 3487 (37%) | |

| Never | 88209 (81%) | 26913 (72%) | 569 (61%) | 7947 (72%) | 5233 (67%) | 5032 (54%) | |

| Physical activity i | Moderate activity ≥ three times a week | 93331 (86%) | 31389 (84%) | 751 (81%) | 9253 (83%) | 6522 (84%) | 7796 (83%) |

See lettered table notes, and Supplementary Appendix 2 for full case definitions.

Criteria not met for depression, GAD, unusual experiences or addiction.

Criteria met for disorder on CIDI-SF lifetime.

Criteria met for both lifetime depression and lifetime mania.

Reported potential hallucination or delusion at any point in their life.

Positively endorsed: ‘Have you been addicted to or dependent on one or more things, including substances (not cigarettes/coffee) or behaviours (such as gambling)?’

Age when mental health questionnaire released, derived from date of birth.

Townsend Material Deprivation Score is based on postcode areas.

Renting in the private sector and renting social housing combined.

From baseline assessment 2007–10.

Criteria met for possible abuse or neglect on Childhood Trauma Screener.

Criteria met for adverse situations as an adult: lack of confiding relationship, abusive relationships and money problems.

Reports one or more of six situations that are known to be triggers for trauma-related disorders.

There is some overlap between the adult screen and loneliness screen, which both ask about confiding relationships: adult screen includes lack of confiding relationship over the adult lifetime; loneliness includes lack of confiding relationship at the time of baseline assessment.

The Supplementary materials have a section on mood disorder, showing the results of analyses of MHQ participants by likely disorder categories (Supplementary Figure MD1). Supplementary Table MD1 shows the features of these groups. The characteristics of people who meet diagnostic criteria for depression appear to be shared by those with subthreshold depressive symptoms. Supplementary Table MD2 shows comorbidity, and demonstrates a gradient effect in the presence of a non-depression syndrome rising from 7% in no depression to 43% in recurrent depression. Supplementary Table MD3 shows an association between the presence of lifetime unipolar depression or bipolar affective disorder and worse scores for current mental health.

Discussion

This paper has described the development, implementation and principal descriptive findings from the UK Biobank MHQ. The implementation of this questionnaire demonstrates that a web-based questionnaire is an acceptable means of collecting mental health information at low cost and large scale. Although the data collection methods might result in more limited data acquisition than conventional interview methods, with associated uncertainties in true diagnostic categorisation, we suggest that the survey achieved an acceptable trade-off between depth of phenotypic information and scale of sample size.

The MHQ achieved a participation rate of 31% of the original UK Biobank participants and 46% of those emailed. This response rate is substantially higher than previous UK Biobank questionnaires, largely owing to the attention paid to ensuring the acceptability of the invitation and questionnaire and the efficient use of reminders. Those who completed the MHQ appeared to be better educated and to have higher socioeconomic employment status than those recruited into UK Biobank overall, and the UK population. Despite this, we found that rates of self-reported diagnoses were similar to population estimates from the HSE. The patterns of association between disorders and demographics were also broadly as predicted by previous research, which adds to the face validity of the questionnaire. For example, depression and anxiety were more common in women, while addiction and alcohol misuse were more common in men, and all disorders were less common in respondents older than 65 years. The decrease in prevalence of lifetime disorder with increasing age has been previously noted in cross-sectional studies, although the causes and implications are not clearly understood. 21 , 22

The ‘healthy volunteer’ selection bias within the UK Biobank has previously been explored. 23 The influence of selection biases on disease prevalence are likely to be particularly strong for mental disorders, where disorder status or symptoms may influence participation in research, 24 , 25 and non-participation has also been associated with many risk factors for these disorders, including polygenic risk. 26 Therefore, the results of the MHQ should not be used to provide prevalence estimates. However, the pattern of the measured risk factors among the participants with mental disorders in the MHQ, including neuroticism, trauma, loneliness and housing tenure, was in accordance with established literature, supporting the use of the data to study the relationships between exposures and outcomes. Previous work on health surveys with selection bias due to non-participation, including UK Biobank, have indicated that although they can be used to give estimates of association, 11 , 24 , 27 bias may occur in some cases. 28 , 29 For example, the relative under-participation of unskilled workers in the MHQ (around 21% of that expected) could mask an association with a variable that was related to unskilled work.

Strengths and limitations

We developed a questionnaire through a consensus approach with clear aims of capturing enough data to characterise participants as having a lifetime history of depression and other phenotypes. Validated instruments were used where possible. The consortium working on the questionnaire included mental health researchers and members of the UK Biobank team working in collaboration to develop the optimum approach. The derived variables of likely categorical diagnoses will be added to the UK Biobank resource, facilitating those less familiar with mental health to use the results efficiently.

The ‘healthy volunteer’ effect may limit applications of the data. Owing to restrictions of time and space, the questionnaire was limited in the topics it could cover. The focus of the questionnaire was on categorical diagnoses rather than dimensional traits, which will tend to confirm conventional ICD/DSM nosology of psychiatric disorder and may not suit some research. 30 In particular, tools were chosen that are based on DSM-IV disorders, which reflects current practice (for example, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines on depression and anxiety use DSM-IV definitions). 31 , 32 Of the disorders with operational classification, all would generalise to DSM-5, except PTSD, 33 and the concepts are valid for ICD-10 disorders, although the threshold of disorder may be different, e.g. depression is diagnosed with fewer symptoms in DSM than in ICD. 31 The questionnaire was heavily reliant on participant report, which may be affected by the stigma of reporting psychiatric symptoms, and tends to underestimate lifetime prevalence through forgetting or re-evaluating distant events. 11 , 21 , 34 We hope that some of these shortcomings can be addressed in the future by a more fine-grained analysis of the MHQ data, supplemented with other data from UK Biobank to create a richer picture of mental health in the cohort.

Conclusions

UK Biobank offers a unique opportunity to research common disorders in a well-characterised longitudinal cohort of UK adults. A detailed MHQ has now been completed by 157 366 participants, including self-report, operationally defined lifetime disorder status, and detailed phenotype information on mood disorder. The proportion of cases and the patterns of participants experiencing symptoms and disorders was as expected, despite a ‘healthy volunteer’ selection bias. Future work on mental health phenotyping for UK Biobank will include validation of Hospital Episode Statistics for mental health diagnoses, validation of general practice records, and triangulation of health record and questionnaire data. Examples of existing projects utilising the UK Biobank MHQ can be seen in Supplementary Appendix 3, with a searchable database of approved research (http://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/approved-research/).

This study also demonstrates the substantial burden of mental disorders. Given the known effects of mental health on physical health, mental health data should interest researchers from every biomedical specialty looking at associations with health and disease. This study suggests that UK Biobank could be a powerful tool for such studies, and, since it is open to all bona fide health researchers for work in the public good, we hope this study will inspire both existing and new users of UK Biobank.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff and participants of UK Biobank, the PROTECT study and the SLaM Service Users Group for their participation.

Funding

This paper represents independent research funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. B.C. is funded by the Scottish Executive Chief Scientist Office (DTF/14/03). E.F. is supported by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC grant agreement no: [324176]. L.M.H. is supported by an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-R3-12-011) in Women's Mental Health. W.L. is supported by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula. D.J.S. is supported by the Lister Institute Prize Fellowship. S.Z. is supported by the NIHR Bristol Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, Department of Health, ERC, Scottish Government, UK Biobank or other funders or institutions.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.12.

References

- 1.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, Beral V, Burton P, Danesh J, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med 2015; 12(3): e1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weissman MM, Brown AS, Talati A. Translational epidemiology in psychiatry: linking population to clinical and basic sciences. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2011; 68(6): 600–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell V. Open science in mental health research. Lancet Psychiatry 2017: doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30244-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet 2007; 370(9590): 859–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newton JN, Briggs ADM, Murray CJL, Dicker D, Foreman KJ, Wang H, et al. Changes in health in England, with analysis by English regions and areas of deprivation, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386(10010): 2257–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt G, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet 2012; 380(9836): 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen BE, Edmondson D, Kronish IM. State of the art review: depression, stress, anxiety, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Hypertens 2015; 28(11): 1295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang C-K, Hayes RD, Broadbent MTM, Hotopf M, Davies E, Møller H, et al. A cohort study on mental disorders, stage of cancer at diagnosis and subsequent survival. BMJ Open 2014; 4(1): e004295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith DJ, Nicholl BI, Cullen B, Martin D, Ul-Haq Z, Evans J, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of probable major depression and bipolar disorder within UK Biobank: cross-sectional study of 172,751 participants. PLoS One 2013; 8(11): e75362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: a review of recent literature. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007; 20(4): 359–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newson RS, Karlsson H, Tiemeier H. Epidemiological fallacies of modern psychiatric research. Nord J Psychiatry 2011; 65(4): 226–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis KA, Sudlow CL, Hotopf M. Can mental health diagnoses in administrative data be used for research? A systematic review of the accuracy of routinely collected diagnoses. BMC Psychiatry 2016; 16(1): 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitman A, Osborn DPJ, King MB. The use of internet-mediated cross-sectional studies in mental health research. BJPsych Adv 2015; 21(3): 175–84. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bridges S. Health Survey for England 2014: Mental Health Problems In HSE 2014 (ed Health and Social Care Information Centre). Office of National Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun B, Wittchen HU. The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short-form (CIDI-SF). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 1998; 7(4): 171–85. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robotham D, Wykes T, Rose D, Doughty L, Strange S, Neale J, et al. Service user and carer priorities in a Biomedical Research Centre for mental health. J Ment Health 2016; 25(3): 185–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wesnes KA, Brooker H, Ballard C, McCambridge L, Stenton R, Corbett A. Utility, reliability, sensitivity and validity of an online test system designed to monitor changes in cognitive function in clinical trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017: doi: 10.1002/gps.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, Katon WJ. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in general primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2014; 36(1): 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carvalho AF, Takwoingi Y, Sales PMG, Soczynska JK, Köhler CA, Freitas TH, et al. Screening for bipolar spectrum disorders: a comprehensive meta-analysis of accuracy studies. J Affect Disord 2015; 172: 337–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joint Health Surveys Unit. Health Survey for England 2014: Volume 2 Methods and Documentation (http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB19295). In HSE 2014 (eds Craig R, Fuller E, Mindell J). Office of National Statistics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Streiner DL, Patten SB, Anthony JC, Cairney J. Has ‘lifetime prevalence’ reached the end of its life? An examination of the concept. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2009; 18(4): 221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Shahly V, Bromet E, Hwang I, McLaughlin KA, et al. Age differences in the prevalence and co-morbidity of DSM-IV major depressive episodes: results from the WHO World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Depress Anxiety 2010; 27(4): 351–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fry A, Littlejohns TJ, Sudlow C, Doherty N, Adamska L, Sprosen T, et al. Comparison of sociodemographic and health-related characteristics of UK Biobank participants with the general population. Am J Epidemiol 2017: doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knudsen AK, Hotopf M, Skogen JC, Øverland S, Mykletun A. The health status of nonparticipants in a population-based health study: The Hordaland Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2010; 172(11): 1306–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atherton K, Fuller E, Shepherd P, Strachan DP, Power C. Loss and representativeness in a biomedical survey at age 45 years: 1958 British birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2008; 62(3): 216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin J, Tilling K, Hubbard L, Stergiakouli E, Thapar A, Davey Smith G, et al. Association of genetic risk for schizophrenia with nonparticipation over time in a population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 2016; 183(12): 1149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Macfarlane GJ, Beasley M, Smith BH, Jones GT, Macfarlane TV. Can large surveys conducted on highly selected populations provide valid information on the epidemiology of common health conditions? An analysis of UK Biobank data on musculoskeletal pain. Br J Pain 2015; 9(4): 203–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Robins JM. A structural approach to selection bias. Epidemiology 2004; 15(5): 615–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sperrin M, Candlish J, Badrick E, Renehan A, Buchan I. Collider bias is only a partial explanation for the obesity paradox. Epidemiology 2016; 27(4): 525–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lilienfeld SO, Treadway MT. Clashing diagnostic approaches: DSM-ICD Versus RDoC. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2016; 12(1): 435–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression in Adults: Recognition and Management NICE Clinical Guideline CG90. NICE, 2009. (updated 2016).

- 32.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Generalised Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder in Adults: Management NICE Clinical Guideline CG113. NICE, 2011. [PubMed]

- 33.American Psychiatric Association. Highlights of Changes from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5: psychiatry.org, 2013.

- 34.Nevin RL. Low validity of self-report in identifying recent mental health diagnosis among US service members completing Pre-Deployment Health Assessment (PreDHA) and deployed to Afghanistan, 2007: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2009; 9(1): 376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]