Abstract

Rationale: The neuromuscular blocking agent cisatracurium may improve mortality for patients with moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Other neuromuscular blocking agents, such as vecuronium, are commonly used and have different mechanisms of action, side effects, cost, and availability in the setting of drug shortages.

Objectives: To determine whether cisatracurium is associated with improved outcomes when compared with vecuronium in patients at risk for and with ARDS.

Methods: Using a nationally representative database, patients who were admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of ARDS or an ARDS risk factor, received mechanical ventilation, and were treated with a continuous infusion of neuromuscular blocking agent for at least 2 days within 2 days of hospital admission were included. Patients were stratified into two groups: those who received cisatracurium or vecuronium. Propensity matching was used to balance both patient- and hospital-specific factors. Outcomes included hospital mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital duration, and discharge location.

Measurements and Main Results: Propensity matching successfully balanced all covariates for 3,802 patients (1,901 per group). There was no significant difference in mortality (odds ratio, 0.932; P = 0.40) or hospital days (–0.66 d; P = 0.411) between groups. However, patients treated with cisatracurium had fewer ventilator days (–1.01 d; P = 0.005) and ICU days (–0.98 d; P = 0.028) but were equally likely to be discharged home (odds ratio, 1.19; P = 0.056).

Conclusions: When compared with vecuronium, cisatracurium was not associated with a difference in mortality but was associated with improvements in other clinically important outcomes. These data suggest that cisatracurium may be the preferred neuromuscular blocking agent for patients at risk for and with ARDS.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, mechanical ventilators, neuromuscular blockade, patient outcome assessment

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

In patients at risk for and with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), mechanical ventilation can cause injury to the lung. Neuromuscular blocking agents may be used to improve oxygenation, decrease ventilatory dyssynchrony, and reduce ventilator-induced lung injury. The neuromuscular blocking agent cisatracurium may improve mortality for patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS. However, it is unknown whether the potential benefits of cisatracurium would be observed with other neuromuscular blocking agents.

What This Study Adds to the Field

When compared with vecuronium, cisatracurium was not associated with a difference in mortality but was associated with a significant reduction in ventilator days and ICU days. These data suggest that cisatracurium may be the preferred neuromuscular blockade agent for patients at risk for and with ARDS.

Despite more than 50 years of research, the mortality from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) remains unacceptably high (1). Importantly, mechanical ventilation can cause injury to the lung—termed ventilator-induced lung injury—in patients with and at risk for ARDS. In patients at risk for ARDS, ventilator-induced lung injury can increase the likelihood of developing ARDS and ultimately increase mortality. Ventilator-induced lung injury can be caused by both large tidal volume and high-pressure ventilation (2). One treatment to minimize ventilator-induced lung injury is low-tidal volume mechanical ventilation of 6 ml/kg ideal body weight. Low tidal volume ventilation reduced mortality in patients with ARDS and reduced pulmonary complications in those at risk for ARDS (3–7). However, low tidal volume ventilation alone does not eliminate the development of ventilator-induced lung injury, and patients may continue to generate both high pressure and large tidal volume through spontaneous efforts. Consequently, methods to prevent such patient–ventilator interactions—termed patient self-inflicted lung injury—and thus reduce the propagation of ventilator-induced lung injury are under active investigation to both prevent and treat ARDS (8).

In patients at risk for and with ARDS, neuromuscular blockade may be used to improve oxygenation, eliminate patient–ventilator interactions, decrease ventilatory dyssynchrony, and reduce ventilator-induced lung injury. A clinical trial of a 48-hour infusion of cisatracurium (initiated within the first 48 h of mechanical ventilation) in patients with moderate to severe ARDS suggested that neuromuscular blockade may improve outcomes in patients with ARDS (9). Neuromuscular blockade is generally thought to improve outcomes by reducing ventilator-induced lung injury. In addition, cisatracurium metabolism does not depend on renal or hepatic function—which may increase its use in patients with multiorgan dysfunction and an increased risk of death. In addition, the chemical structure of cisatracurium may reduce the risk of ICU-associated weakness when compared with other neuromuscular blockade agents (10). Consequently, other neuromuscular blockade agents may not have the same potential beneficial effects on patient outcomes.

We conducted a multicenter, observational study in patients with and at risk for ARDS to determine whether patients treated with cisatracurium or vecuronium, another commonly used neuromuscular blockade agent, had similar outcomes. Determining whether the beneficial effects of neuromuscular blockade are specific to cisatracurium is important for several reasons. First, differences in patient outcomes could be explained by mechanistic differences in neuromuscular blockade function or by the side-effect profiles of different agents. Second, these results will determine whether the potentially beneficial effects of cisatracurium balance its nearly threefold increase in cost over vecuronium (11). Finally, if the beneficial effects of cisatracurium are similar to those of vecuronium, then the use of vecuronium can be supported in the setting of drug shortages that have occurred with cisatracurium.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a multicenter, observational cohort study of the Premier Incorporated Perspective Database, a cohort of more than 5.4 million unique ICU admissions nationally from January 2010 through December 2014. The database has been described in detail previously (12–15). The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board approved this study (#16-0505).

Patient Population

Mechanically ventilated, ICU patients with a diagnosis of ARDS or a known ARDS risk factor and who received at least 2 days of a continuous infusion of neuromuscular blockade within the first 2 days of hospital admission were included. ARDS risk factors included acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, pneumonia, sepsis, trauma, burns, and other diagnoses or treatments (i.e., multiple transfusions) (16). Patients with ARDS risk factors were included because of the underdiagnosis of ARDS and the potential benefit of decreasing ventilator-induced lung injury, reducing the development of ARDS, and minimizing other pulmonary complications in these patients (17). Patient diagnosis was determined on the basis of the International Classification of Disease Codes, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) (additional details may be found in Table E1 in the online supplement) (18). To minimize unmeasured confounding by worsening severity of illness after admission, and based on previous clinical trials, patients were included if they received at least two consecutive days of either cisatracurium or vecuronium by continuous intravenous infusions, exclusively, within 48 hours of hospital admission (9). Vecuronium was selected as it was the second most commonly used neuromuscular blockade agent in the Premier database. Other agents, including atracurium (1,533 patients) and pancuronium (1,271 patients), were less frequently utilized as continuous infusions.

Outcomes

The following outcome measures were determined: hospital mortality, ventilator days, ICU days, hospital days, and discharge home versus elsewhere.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using previously published methodology with modifications to include variables pertinent to this study (19). Patient characteristics included age; sex; the diagnosis of ARDS, pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute liver failure, sepsis, septic shock; the Elixhauser comorbidity index; and the year and quarter of admission. The Elixhauser index is a comprehensive set of 30 comorbidities that correlate with patient outcomes when hospitalized (20). We ensured that the diagnosis of pneumonia, ARDS, DIC, liver failure, sepsis, septic shock, cancer, or COPD was present at the time of admission. Finally, the numbers of vasopressor days, renal failure days, and mechanical ventilation days before the initiation of neuromuscular blockade were included. Hospital characteristics included the following: hospital region, hospital size, rural versus urban status, and teaching versus nonteaching status. Urban status and teaching status of each hospital was defined according to the Premier database. These data were compared between groups, using the χ2 test for categorical data and the unpaired t test or Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables.

A nonparsimonious regression model was used to produce a propensity score for treatment with vecuronium, using the hospital and patient characteristics described above. For the propensity-matched analysis (primary analysis), each patient in the vecuronium group was matched 1:1 with a patient in the cisatracurium group to the nearest third decimal point, using a nearest neighbor algorithm (21). We chose to match to the third decimal point (caliper 0.001) because it was less than the commonly suggested 0.2 SD of the propensity score logit, resulting in both reasonable matches and good overall sample size. Final models included each hospital as a random effect and all patient and hospital characteristics used to calculate the propensity score. In addition, multivariable regression modeling, including all patient and hospital characteristics used to calculate the propensity score, was used to confirm these findings (secondary analysis). Finally, to assess whether hospitals that use only cisatracurium or vecuronium alone may disproportionally influence outcomes, a sensitivity analysis stratified by hospitals that use cisatracurium alone, vecuronium alone, or both agents was performed. All analysis was performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of an abstract at the 2017 American Thoracic Society Meeting (22).

Results

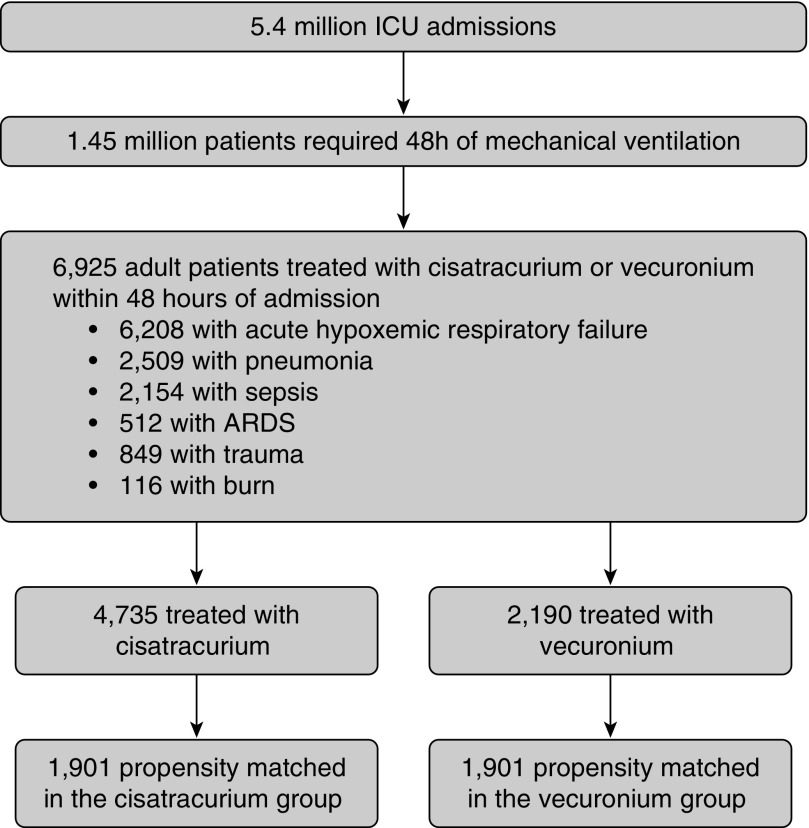

Of more than 5.4 million ICU admissions, 1.45 million required 48 hours of mechanical ventilation. Of these, a total of 13,436 patients were identified who received either cisatracurium or vecuronium for at least 48 hours, of which 6,925 patients received neuromuscular blockade within 48 hours of admission. All patients had at least one ARDS risk factor; 6,208 patients had acute hypoxemic respiratory failure, 2,509 patients had pneumonia, 2,154 patients had sepsis, 849 patients had trauma, and 116 patients had burns. A total of 512 patients received an ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for ARDS (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inclusion flow diagram. ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome.

A total of 4,735 patients received cisatracurium and 2,190 patients received vecuronium. Overall, patients in the cisatracurium group were older (mean ± SD, 54.3 ± 16.2 vs. 50.8 ± 17.1 yr; P < 0.001) and more likely female (34.7 vs. 28.7%; P < 0.001) compared with the vecuronium group. At hospital admission, patients in the cisatracurium group had increased rates of pneumonia (37.6 vs. 33.4%; P = 0.001) but were less likely to have ARDS (5.7 vs. 11.0%; P < 0.001) when compared with the vecuronium group (Table 1). However, patients in the cisatracurium group were more likely to have severe sepsis (20.1 vs. 12.4%; P < 0.001), septic shock (15.7 vs. 8.5%; P < 0.001), liver disease (14.2 vs. 10.4%; P < 0.001), and a greater number of Elixhauser comorbidities (median [interquartile range], 11.0 [5–18] vs. 9.0 [2–16]; P < 0.001) when compared with the vecuronium group at hospital admission. Patients in the cisatracurium group received more days of neuromuscular blockade (3.3 vs. 3.1 d; P = 0.003) than those receiving vecuronium.

Table 1.

Baseline Covariates of Entire Study Population before Propensity Matching

| All Subjects (N = 6,925) | Cisatracurium (n = 4,735) | Vecuronium (n = 2,190) | P Value | Standardized Mean Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 53.2 (16.60) | 54.3 (16.24) | 50.8 (17.10) | <0.001 | −0.2112 |

| Sex | 2,270 (32.8%) | 1,642 (34.7%) | 628 (28.7%) | <0.001 | −0.1293 |

| | |||||

| Race | |||||

| White | 4,624 (66.8%) | 3,103 (65.5%) | 1,521 (69.5%) | <0.001 | 0.1351 |

| Black | 986 (14.2%) | 675 (14.3%) | 311 (14.2%) | ||

| Hispanic | 84 (1.2%) | 47 (1.0%) | 37 (1.7%) | ||

| Other | 1,231 (17.8%) | 910 (19.2%) | 321 (14.7%) | ||

| | |||||

| Admission year* | |||||

| 2010 | 1,024 (14.8%) | 556 (11.7%) | 468 (21.3%) | <0.001 | 0.4363 |

| 2011 | 1,373 (19.8%) | 879 (18.5%) | 494 (22.7%) | ||

| 2012 | 1,535 (22.2%) | 1,025 (21.6%) | 510 (23.3%) | ||

| 2013 | 1,630 (23.5%) | 1,154 (24.5%) | 476 (21.7%) | ||

| 2014 | 1,363 (19.7%) | 1,121 (23.7%) | 242 (11.0%) | ||

| | |||||

| Patient characteristics before initiation of neuromuscular blockade | |||||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 512 (7.4%) | 271 (5.7%) | 241 (11.0%) | <0.001 | 0.1916 |

| Pneumonia | 2,509 (36.2%) | 1,778 (37.6%) | 731 (33.4%) | 0.001 | −0.0873 |

| Severe sepsis | 1,224 (17.7%) | 953 (20.1%) | 271 (12.4%) | <0.001 | −0.2113 |

| Septic shock | 930 (13.4%) | 743 (15.7%) | 187 (8.5%) | <0.001 | −0.2205 |

| Liver disease | 898 (13.0%) | 671 (14.2%) | 227 (10.4%) | <0.001 | −0.1162 |

| DIC syndrome | 110 (1.6%) | 85 (1.8%) | 25 (1.1%) | 0.045 | −0.0544 |

| COPD | 1,329 (19.2%) | 945 (20.0%) | 384 (17.5%) | 0.017 | −0.0621 |

| Metastatic cancer | 107 (1.5%) | 77 (1.6%) | 30 (1.4%) | 0.422 | −0.0211 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities (count) | 11.0 (4–18) | 11.0 (5–18) | 9.0 (2–16) | <0.001 | −0.2249 |

| Days needing mechanical ventilation before neuromuscular blockade | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.977 | −0.0007 |

| Days needing vasopressors before neuromuscular blockade | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) | 0.019 | −0.0598 |

| Days with renal failure before neuromuscular blockade | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | <0.001 | −0.1102 |

| | |||||

| Patient characteristics at discharge | |||||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 921 (13.3%) | 558 (11.8%) | 363 (16.6%) | <0.001 | 0.1377 |

| Pneumonia | 3,882 (56.1%) | 2,642 (55.8%) | 1,240 (56.6%) | 0.521 | 0.0166 |

| Severe sepsis | 1,656 (23.9%) | 1,263 (26.7%) | 393 (17.9%) | <0.001 | −0.2108 |

| Septic shock | 1,274 (18.4%) | 1,004 (21.2%) | 270 (12.3%) | <0.001 | −0.2393 |

| Liver disease | 1,281 (18.5%) | 959 (20.3%) | 322 (14.7%) | <0.001 | −0.1465 |

| DIC syndrome | 235 (3.4%) | 181 (3.8%) | 54 (2.5%) | 0.004 | −0.0778 |

| COPD | 1,369 (19.8%) | 971 (20.5%) | 398 (18.2%) | 0.024 | −0.0591 |

| Metastatic cancer | 107 (1.5%) | 77 (1.6%) | 30 (1.4%) | 0.422 | −0.0211 |

| Delirium/encephalopathy | 920 (13.3%) | 687 (14.5%) | 233 (10.6%) | <0.001 | −0.1169 |

| Critical illness myopathy/neuropathy | 141 (2.0%) | 111 (2.3%) | 30 (1.4%) | 0.008 | −0.0722 |

| Days needing vasopressors | 2.0 (1–4) | 2.0 (1–4) | 2.0 (0–4) | <0.001 | −0.1196 |

| Days with renal failure | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | <0.001 | −0.1608 |

| | |||||

| Hospital characteristics | |||||

| Number of beds | |||||

| <200 | 590 (8.5%) | 441 (9.3%) | 149 (6.8%) | <0.001 | 0.2055 |

| 200–300 | 815 (11.8%) | 523 (11.0%) | 292 (13.3%) | ||

| 301–400 | 1,671 (24.1%) | 1,223 (25.8%) | 448 (20.5%) | ||

| 401–500 | 1,299 (18.8%) | 918 (19.4%) | 381 (17.4%) | ||

| >500 | 2,550 (36.8%) | 1,630 (34.4%) | 920 (42.0%) | ||

| Teaching | |||||

| No | 3,075 (44.4%) | 2,207 (46.6%) | 868 (39.6%) | <0.001 | 0.1412 |

| Yes | 3,850 (55.6%) | 2,528 (53.4%) | 1,322 (60.4%) | ||

| Urban/rural | |||||

| Rural | 471 (6.8%) | 322 (6.8%) | 149 (6.8%) | 0.996 | −0.0001 |

| Urban | 6,454 (93.2%) | 4,413 (93.2%) | 2,041 (93.2%) | ||

| Provider region | |||||

| Midwest | 1,424 (20.6%) | 951 (20.1%) | 473 (21.6%) | <0.001 | 0.3296 |

| Northeast | 1,001 (14.5%) | 689 (14.6%) | 312 (14.2%) | ||

| South | 3,445 (49.7%) | 2,541 (53.7%) | 904 (41.3%) | ||

| West | 1,055 (15.2%) | 554 (11.7%) | 501 (22.9%) | ||

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

Data are presented as mean (SD), n (%), or median (interquartile range).

Although the actual match was performed by year and quarter, only yearly data are shown here for ease of presentation.

Propensity-Matched Analysis (Primary Analysis)

After propensity matching 86% of patients in the vecuronium group were successfully matched 1:1 with an equal number of patients in the cisatracurium group, yielding a total of 1,901 patients in each group. Diagnostic evaluation of the propensity matching is included in the online supplement (Table E2 and Figures E1–E3). Propensity matching eliminated differences between admission patient and hospital characteristics and reduced differences in patient characteristics at discharge (Table 2). After propensity matching, patients in the cisatracurium group received more days of neuromuscular blockade when compared with those in the vecuronium group (3.2 vs. 3.0 d; P = 0.002).

Table 2.

Values of Covariates after Propensity Matching in Matched Patients

| All Subjects (N = 3,802) | Cisatracurium (n = 1,901) | Vecuronium (n = 1,901) | P Value | Standardized Mean Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 51.9 (16.80) | 52.0 (16.76) | 51.9 (16.84) | 0.837 | −0.0067 |

| Female | 1,160 (30.5%) | 579 (30.5%) | 581 (30.6%) | 0.944 | 0.0023 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 2,540 (66.8%) | 1,207 (63.5%) | 1,333 (70.1%) | <0.001 | 0.2445 |

| Black | 515 (13.5%) | 236 (2.4%) | 279 (14.7%) | ||

| Hispanic | 48 (1.3%) | 20 (1.1%) | 28 (1.5%) | ||

| Other | 699 (18.4%) | 438 (23.0%) | 261 (13.7%) | ||

| Admission year* | |||||

| 2010 | 689 (18.1%) | 357 (18.8%) | 332 (17.4%) | 0.999 | 0.0764 |

| 2011 | 848 (22.3%) | 424 (22.3%) | 424 (22.3%) | ||

| 2012 | 890 (23.4%) | 433 (22.8%) | 457 (24.1%) | ||

| 2013 | 883 (23.3%) | 434 (22.8%) | 449 (23.6%) | ||

| 2014 | 492 (12.9%) | 253 (13.3%) | 239 (12.6%) | ||

| Patient characteristics before initiation of neuromuscular blockade | |||||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 336 (8.8%) | 171 (9.0%) | 165 (8.7%) | 0.732 | −0.0111 |

| Pneumonia | 1,321 (34.7%) | 654 (34.4%) | 667 (35.1%) | 0.658 | 0.0144 |

| Severe sepsis | 534 (14.0%) | 269 (14.2%) | 265 (13.9%) | 0.852 | −0.0061 |

| Septic shock | 378 (9.9%) | 192 (10.1%) | 186 (9.8%) | 0.745 | −0.0105 |

| Liver disease | 443 (11.7%) | 227 (11.9%) | 216 (11.4%) | 0.578 | −0.0180 |

| DIC syndrome | 45 (1.2%) | 22 (1.2%) | 23 (1.2%) | 0.881 | 0.0049 |

| COPD | 704 (18.5%) | 347 (18.3%) | 357 (18.8%) | 0.676 | 0.0135 |

| Metastatic cancer | 62 (1.6%) | 32 (1.7%) | 30 (1.6%) | 0.798 | −0.0083 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities (count) | 10.0 (3–16) | 10.0 (3–16) | 10.0 (3–17) | 0.586 | 0.0177 |

| Days needing mechanical ventilation before neuromuscular blockade | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.545 | 0.0196 |

| Days needing vasopressors before neuromuscular blockade | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) | 1.0 (0–3) | 0.657 | 0.0143 |

| Days with renal failure before neuromuscular blockade | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.679 | 0.0134 |

| | |||||

| Patient characteristics at discharge | |||||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 564 (14.8%) | 294 (15.5%) | 270 (14.2%) | 0.274 | −0.0355 |

| Pneumonia | 2,108 (55.4%) | 1,017 (53.5%) | 1,091 (57.4%) | 0.016 | 0.0784 |

| Severe sepsis | 774 (20.4%) | 411 (21.6%) | 363 (19.1%) | 0.053 | −0.0627 |

| Septic shock | 545 (14.3%) | 292 (15.4%) | 253 (13.3%) | 0.071 | −0.0586 |

| Liver disease | 643 (16.9%) | 340 (17.9%) | 303 (15.9%) | 0.110 | −0.0519 |

| DIC syndrome | 111 (2.9%) | 59 (3.1%) | 52 (2.7%) | 0.500 | −0.0219 |

| COPD | 729 (19.2%) | 358 (18.8%) | 371 (19.5%) | 0.592 | 0.0174 |

| Metastatic cancer | 62 (1.6%) | 32 (1.7%) | 30 (1.6%) | 0.798 | −0.0083 |

| Delirium/encephalopathy | 485 (12.8%) | 268 (14.1%) | 217 (11.4%) | 0.013 | −0.0805 |

| Critical illness myopathy/neuropathy | 68 (1.8%) | 42 (2.2%) | 26 (1.4%) | 0.052 | −0.0635 |

| Days needing vasopressors | 2.0 (1–4) | 2.0 (1–4) | 2.0 (1–4) | 0.057 | −0.0617 |

| Days with renal failure | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.0 (0–0) | 0.040 | −0.0665 |

| Hospital characteristics | |||||

| Number of beds | |||||

| <200 | 257 (6.8%) | 123 (6.5%) | 134 (7.0%) | 0.898 | 0.0337 |

| 200–300 | 485 (12.8%) | 240 (12.6%) | 245 (12.9%) | ||

| 301–400 | 809 (21.3%) | 415 (21.8%) | 394 (20.7%) | ||

| 401–500 | 696 (18.3%) | 347 (18.3%) | 349 (18.4%) | ||

| >500 | 1,555 (40.9%) | 776 (40.8%) | 779 (41.0%) | ||

| Teaching | |||||

| No | 1,512 (39.8%) | 753 (39.6%) | 759 (39.9%) | 0.842 | −0.0064 |

| Yes | 2,290 (60.2%) | 1,148 (60.4%) | 1,142 (60.1%) | ||

| Urban/rural | |||||

| Rural | 274 (7.2%) | 137 (7.2%) | 137 (7.2%) | 1.000 | 0.0000 |

| Urban | 3,528 (92.8%) | 1,764 (92.8%) | 1,764 (92.8%) | ||

| Provider region | |||||

| Midwest | 765 (20.1%) | 370 (19.5%) | 395 (20.8%) | 0.780 | 0.0338 |

| Northeast | 551 (14.5%) | 277 (14.6%) | 274 (14.4%) | ||

| South | 1,743 (45.8%) | 882 (46.4%) | 861 (45.3%) | ||

| West | 743 (19.5%) | 372 (19.6%) | 371 (9.5%) | ||

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulopathy.

Data are presented as mean (SD), n (%), or median (interquartile range).

While the actual match was performed by year and quarter, only yearly data are shown here for ease of presentation.

In a fully adjusted, propensity-matched model, patients treated with cisatracurium experienced no difference in mortality (odds ratio [OR], 0.93; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.79–1.10; P = 0.40) or hospital length of stay (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, –0.75 to 1.83; P = 0.41) compared with patients treated with vecuronium. However, patients treated with cisatracurium experienced fewer ventilator days (OR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.30–1.72; P = 0.005) and fewer ICU days (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.11–1.86; P = 0.028) compared with patients treated with vecuronium. Moreover, patients who were treated with cisatracurium were equally likely to be discharged home as patients treated with vecuronium (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.00–1.43; P = 0.056) (Table 3). There were no significant differences in outcomes between hospitals that used only cisatracurium, only vecuronium, or both agents (see the online supplement).

Table 3.

Results of Propensity-Matched and Multivariate Analysis in Patients with or at Risk for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

| Propensity-Matched Analysis (N = 3,802) |

Multivariable Analysis (N = 6,925) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | P Value | Estimate | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Odds of mortality, OR | 0.93 | 0.79 to 1.10 | 0.40 | 0.91 | 0.80 to 1.02 | 0.11 |

| Difference in ventilator days | 1.01 | 0.30 to 1.72 | 0.005 | 0.78 | 0.31 to 1.25 | 0.001 |

| Difference in ICU days | 0.98 | 0.11 to 1.86 | 0.028 | 0.73 | 0.17 to 1.30 | 0.011 |

| Difference in hospital days | 0.66 | −0.75 to 1.83 | 0.41 | 0.57 | −0.29 to 1.44 | 0.05 |

| Odds of discharge to home, OR | 1.19 | 1.00 to 1.43 | 0.056 | 1.19 | 1.05 to 1.37 | 0.008 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Multivariable Analysis of the Entire Cohort

The entire cohort (6,925 patients) was then analyzed using multivariable regression after adjusting for differences in the same patient and hospital characteristic used to calculate the propensity score. This multivariable analysis demonstrated that patients treated with cisatracurium experienced no difference in mortality rate when compared with patients treated with vecuronium (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.80–1.02; P = 0.11). However, patients treated with cisatracurium experienced fewer ventilator days (0.78; 95% CI, 0.31–1.25; P = 0.001), fewer ICU days (0.73; 95% CI, 0.17–1.30; P = 0.011), but similar hospital days (0.57; 95% CI, –0.29 to 1.44; P = 0.05) than patients treated with vecuronium. Finally, patients who were treated with cisatracurium experienced an increased likelihood to be discharged home than patients treated with vecuronium (OR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.05–1.37; P = 0.008) (Table 3).

Discussion

We performed a multicenter, observational cohort study to assess outcomes in patients at risk for or with ARDS who were treated with cisatracurium or vecuronium infusions. We demonstrated that there was no significant association between mortality or length of hospitalization and treatment with cisatracurium or vecuronium. However, there was an association of fewer ventilator days and ICU days between patients treated with cisatracurium and patients treated with vecuronium. Patients who survived to hospital discharge and were treated with cisatracurium were not significantly more likely to be discharged home than patients treated with vecuronium in the propensity-matched model, but were more likely to be discharged home in the linear regression model.

A prior randomized control trial demonstrated that a 48-hour infusion of cisatracurium within the first 48 hours of mechanical ventilation improved 90-day adjusted mortality, and decreased ventilator days and ICU days, in patients with moderate-to-severe ARDS when compared with placebo (9). In a separate study, the use of cisatracurium was associated with decreased markers of inflammation in both bronchial alveolar lavage and serum in patients with ARDS compared with placebo (23). Similarly, Steingrub and colleagues demonstrated that treatment with any neuromuscular blockade agent was associated with reduced mortality in patient with pulmonary sepsis when compared with usual care (24). However, it remained unclear whether these results were specific to cisatracurium alone, or could be generalizable to other neuromuscular blockade agents. Our findings suggest that cisatracurium is at least equal to and may be superior to vecuronium, another commonly used neuromuscular blockade agent.

There are multiple mechanisms by which neuromuscular blockade agents may decrease ventilator-induced lung injury and thus improve mortality. At least three mechanisms generalizable to all neuromuscular blockade agents have been proposed to explain this trend toward improvement in mortality with neuromuscular blockade (25). First, neuromuscular blockade may eliminate ventilator dyssynchrony and therefore reduce ventilator-induced lung injury. Second, by decreasing oxygen consumption by muscular activity and improving systemic oxygenation, neuromuscular blockade could reduce respiratory demand and cardiac output. Decreasing respiratory demand may decrease ventilator-induced lung injury from high minute ventilation. Decreasing cardiac output may decrease ventilator-induced lung injury from pulmonary vascular strain. Third, neuromuscular blockade may reduce atelectrauma by reducing pulmonary derecruitment with spontaneous breathing.

Cisatracurium may improve outcomes over vecuronium through additional mechanisms not directly related to reducing ventilator-induced lung injury. First, cisatracurium is cleared by Hofmann elimination; a mechanism that is independent of renal or hepatic function (10). Other neuromuscular blockade agents relay on primarily renal or hepatic clearance and thus are more slowly eliminated in critically ill patients, even without other organ failure (26). Thus, these other neuromuscular blockade agents may have continued effect after the infusion has been stopped, potentially increasing the need for sedation and mechanical ventilation. Second, the chemical structure of cisatracurium (a benzylisoquinolinium) may decrease the risk of ICU-associated weakness when compared with other neuromuscular blockade agents (aminosteroids) (10). ICU-associated weakness results in prolonged physical rehabilitation, and decreased quality of life in survivors (27).

In this context, our findings add information to the clinical management of ARDS. Despite the cohort of patients who received cisatracurium having a greater baseline severity of disease, after statistical adjustment, we could find no difference in mortality between patients treated with cisatracurium compared with vecuronium in our primary analysis. If the mortality benefit of neuromuscular blockade observed in clinical trials derived from a class effect, these findings suggest that both drugs are equally efficacious at reducing mortality. However, cisatracurium demonstrated a consistent decrease in ventilator days and ICU days compared with vecuronium across multiple methods of analysis. These findings suggest that the nonpulmonary effects of cisatracurium—specifically its decreased association with ICU-associated weakness and faster metabolic clearance—may lead to decreased lengths of stay (10). This is additionally supported by the finding that hospital survivors treated with cisatracurium were more likely to be discharged to home in the linear regression model. Although the likelihood of discharge to home was not significantly different in the propensity-matched model, the magnitude of the difference between groups was consistent between the primary propensity analysis and the linear regression analysis, suggesting that the study may be underpowered to detect a difference after propensity matching.

Our study has several strengths. First, the Premier Incorporated Database included pharmacy data for a large number of critically ill patients. Although use of a large administrative database is associated with several limitations detailed below, the Premier Incorporated Database provides one of the few available options to answer these study questions. Recruiting patients into a large randomized control trial to answer these questions is likely impractical. Second, we implemented a variety of statistical methods—propensity matching, propensity modeling, and multivariate regression—all of which yielded consistent results. We controlled for differences between hospitals by including each hospital as a random effect in our final mixed-effects models. Third, cisatracurium was inherently used in patients with an increased severity of disease. Patients treated with cisatracurium were older and had more severe disease as measured by evidence of multiorgan dysfunction (more septic shock, liver failure, renal failure, and encephalopathy). Despite this bias, we still demonstrated improved outcomes with cisatracurium.

Our study also has several limitations. First, multiple unmeasured confounding variables may exist. However, there are several reasons why indication bias does not explain these results. First, we limited our analysis to patients who received neuromuscular blockade within 48 hours of hospital admission to decrease the chance of significant changes in patient status from initial admission diagnosis. Second, patients treated with cisatracurium were older and had more evidence of multiorgan failure than did patients treated with vecuronium at baseline. These data should bias our findings in favor of vecuronium. Despite this, our analysis showed improved outcomes with cisatracurium. Third, clinically there is little reason to preferentially use vecuronium over cisatracurium in patients with multiorgan failure given its dependence on hepatic and renal function for clearance. Finally, we utilized propensity matching, regression modeling, and sensitivity analysis to control for a variety of patient and hospital confounders. However, indication bias remains a clear limitation and may still exist despite these precautions. Second, the Premier Database does not include laboratory results, imaging findings, or details of clinical decision making. Thus, we are unable to adjust for severity of illness scores such as APACHE (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) or SAPS (Simplified Acute Physiology Score) or severity of ARDS (as determined by the P/F ratio [the ratio of PaO2 to the fraction of inspired oxygen]). This prevented an analysis of patients who were eligible for neuromuscular blockade but did not receive neuromuscular blockade. Third, diagnoses are determined using ICD-9-CM codes. Misclassification and underclassification are possible. Although misclassification is often assumed to be nondifferential and thus bias results toward the null, this may not be a true assumption and we are unable to evaluate for systemic bias introduced by nondifferential or differential misclassification (28–30). Fourth, the patients’ primary indication for mechanical ventilation is unknown. Ideally, we would study patients with severe hypoxemic respiratory failure. Like Papazian and colleagues (9), we included patients who received neuromuscular blockade within 48 hours of initiation of mechanical ventilation to avoid unmeasured confounding introduced by change in clinical status after hospital admission. Fifth, drug administration is based on hospital charges. Although we can determine whether a specific infusion was charged to the patient, we cannot determine how much of the infusion was administered to the patient. Sixth, because there was not a significance difference in mortality, total ventilator days—and not ventilator-free days—were used as an outcome variable to overcome the inherent difficulty of modeling a severely nonnormal outcome such as free days. Thus, it is possible that part of the reduction in ventilator days is associated with nonstatistically significant differences in mortality between groups. Seventh, propensity matching results in studying only a subset of the population, which may limit generalizability. Finally, this is an observational study and thus causal associations cannot be determined.

Conclusions

When compared with vecuronium, cisatracurium was associated with improved outcomes for patients at risk for and with ARDS. Therefore, cisatracurium may be the neuromuscular blockade agent of choice for these patients. Further research is needed to evaluate the mechanism underlying these differences, and to validate these findings in other cohorts of critically ill patients.

Footnotes

Supported by the NIH (K24 HL069223) and by an NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) Colorado Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) (UL1 TR001082) (P.D.S. and M.M.). R.W.V. received funding from the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (CIA092054 and 150001F).

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to data acquisition and analysis, and revision of intellectual content; approved the definitive version; and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1132OC on December 14, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Colorado Pulmonary Outcomes Research Group (CPOR)

References

- 1.Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE, Ashbaugh DG, Bigelow DB, Petty TL, Levine BE. Acute respiratory distress in adults. The Lancet, Saturday 12 August 1967 [review of the classics] Crit Care Resusc. 2005;7:60–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webb HH, Tierney DF. Experimental pulmonary edema due to intermittent positive pressure ventilation with high inflation pressures: protection by positive end-expiratory pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974;110:556–565. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.5.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Futier E, Constantin J-M, Paugam-Burtz C, Pascal J, Eurin M, Neuschwander A, et al. IMPROVE Study Group. A trial of intraoperative low-tidal-volume ventilation in abdominal surgery. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:428–437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serpa Neto A, Cardoso SO, Manetta JA, Pereira VGM, Espósito DC, Pasqualucci MDOP, et al. Association between use of lung-protective ventilation with lower tidal volumes and clinical outcomes among patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012;308:1651–1659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guay J, Ochroch EA. Intraoperative use of low volume ventilation to decrease postoperative mortality, mechanical ventilation, lengths of stay and lung injury in patients without acute lung injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD011151. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011151.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neto AS, Simonis FD, Barbas CSV, Biehl M, Determann RM, Elmer J, et al. PROtective Ventilation Network Investigators. Lung-protective ventilation with low tidal volumes and the occurrence of pulmonary complications in patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome: a systematic review and individual patient data analysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:2155–2163. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:438–442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1081CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papazian L, Forel J-M, Gacouin A, Penot-Ragon C, Perrin G, Loundou A, et al. ACURASYS Study Investigators. Neuromuscular blockers in early acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1107–1116. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price D, Kenyon NJ, Stollenwerk N. A fresh look at paralytics in the critically ill: real promise and real concern. Ann Intensive Care. 2012;2:43. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-2-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Red Book Online. Greenwood Village, CO: Truven Health Analytics [accessed 2016 Apr 4]. Available from: http://micromedex.com/products/product-suites/clinical-knowledge/redbook.

- 12.Lindenauer PK, Pekow PS, Lahti MC, Lee Y, Benjamin EM, Rothberg MB. Association of corticosteroid dose and route of administration with risk of treatment failure in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JAMA. 2010;303:2359–2367. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercaldi CJ, Reynolds MW, Turpin RS. Methods to identify and compare parenteral nutrition administered from hospital-compounded and premixed multichamber bags in a retrospective hospital claims database. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2012;36:330–336. doi: 10.1177/0148607111412974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnett NP, Apodaca TR, Magill M, Colby SM, Gwaltney C, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Moderators and mediators of two brief interventions for alcohol in the emergency department. Addiction. 2010;105:452–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02814.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Landon J, Walker AM. Aprotinin during coronary-artery bypass grafting and risk of death. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:771–783. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a clinical review. Lancet. 2007;369:1553–1564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, Fan E, Brochard L, Esteban A, et al. LUNG SAFE Investigators; ESICM Trials Group. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA. 2016;315:788–800. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munshi L, Gershengorn HB, Fan E, Wunsch H, Ferguson ND, Stukel TA, et al. Adjuvants to mechanical ventilation for acute respiratory failure: adoption, de-adoption, and factors associated with selection. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:94–102. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-438OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kiser TH, Allen RR, Valuck RJ, Moss M, Vandivier RW. Outcomes associated with corticosteroid dosage in critically ill patients with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;189:1052–1064. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0058OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rassen JA, Doherty M, Huang W, Schneeweiss S. Pharmacoepidemiology toolbox. 2013 [accessed 2017 May 1]. Available from: http://www.hdpharmacoepi.org.

- 22.Sottile P, Kiser TH, Burnham EL, Ho M, Allen RR, Vandivier RW, et al. Mortality in intubated patients treated with vecuronium or cisatracurium [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:A2779. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forel J-M, Roch A, Marin V, Michelet P, Demory D, Blache J-L, et al. Neuromuscular blocking agents decrease inflammatory response in patients presenting with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2749–2757. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239435.87433.0D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steingrub JS, Lagu T, Rothberg MB, Nathanson BH, Raghunathan K, Lindenauer PK. Treatment with neuromuscular blocking agents and the risk of in-hospital mortality among mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:90–96. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829eb7c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slutsky AS. Neuromuscular blocking agents in ARDS. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1176–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1007136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prielipp RC, Coursin DB, Scuderi PE, Bowton DL, Ford SR, Cardenas VJ, Jr, et al. Comparison of the infusion requirements and recovery profiles of vecuronium and cisatracurium 51W89 in intensive care unit patients. Anesth Analg. 1995;81:3–12. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, Tomlinson G, Diaz-Granados N, Cooper A, et al. Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–1304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogburn EL, VanderWeele TJ. On the nondifferential misclassification of a binary confounder. Epidemiology. 2012;23:433–439. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824d1f63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Martino M, Fusco D, Colais P, Pinnarelli L, Davoli M, Perucci CA. Differential misclassification of confounders in comparative evaluation of hospital care quality: caesarean sections in Italy. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1049. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funk MJ, Landi SN. Misclassification in administrative claims data: quantifying the impact on treatment effect estimates. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2014;1:175–185. doi: 10.1007/s40471-014-0027-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]