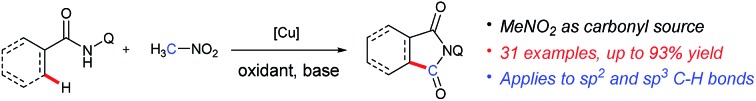

A copper-promoted site-selective carbonylation of sp2 and sp3 C–H bonds with nitromethane as an unprecedented source of carbonyl carbon is described.

A copper-promoted site-selective carbonylation of sp2 and sp3 C–H bonds with nitromethane as an unprecedented source of carbonyl carbon is described.

Abstract

Copper-promoted direct carbonylation of unactivated sp3 C–H and aromatic sp2 C–H bonds of amides was developed using nitromethane as a novel carbonyl source. The sp3 C–H functionalization showed high site-selectivity by favoring the C–H bonds of α-methyl groups. The sp2 C–H carbonylation featured high regioselectivity and good functional group compatibility. Kinetic isotope effect studies indicated that the sp3 C–H bond breaking step is reversible, whereas the sp2 C–H bond cleavage is an irreversible but not the rate-determining step. Control experiments showed that a nitromethyl intermediate should be involved in the present reaction.

Introduction

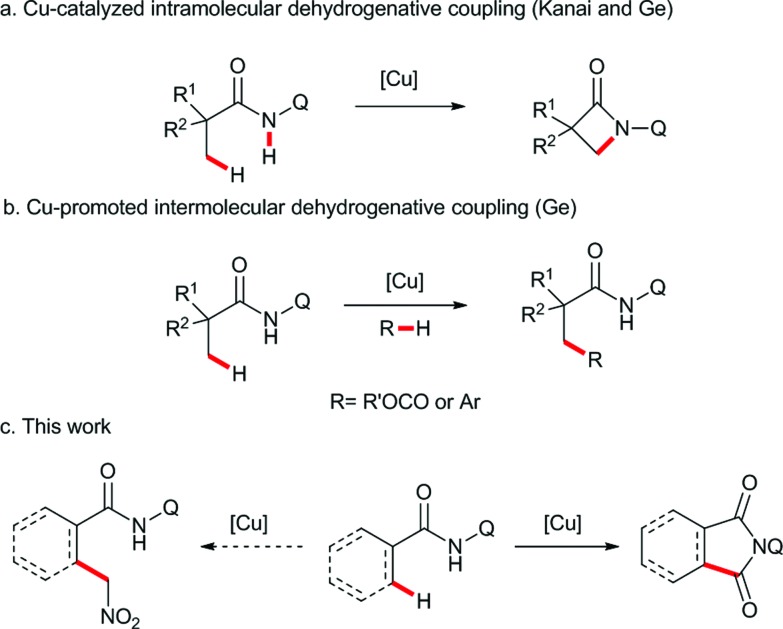

Transition metal-catalyzed direct C–H functionalization is one of the most convenient and efficient tools for selective C–C bond formation, and significant advances have been accomplished in this field during the past few years.1 Among the methods in this category, directing-group-assisted cross dehydrogenative coupling has attracted considerable attention due to its high regioselectivity and efficiency.2 In 2007, Miura and co-workers reported the first example of ligand-assisted regioselective copper-promoted cross dehydrogenative coupling of sp2 C–H bonds of 2-phenyl-pyridines and benzoxazoles.3 Following this pioneering study, a variety of nucleophiles and substrates were proven to be effective in this process.4 In these transformations, employing noble metals, such as palladium, rhodium, ruthenium or iridium, can be avoided, and therefore the reactions are more economical and synthetically useful than their counterparts. Recently, the copper-promoted direct functionalization of unactivated sp3 C–H bonds has also been achieved using bidentate directing groups. The intramolecular sp3 C–H amidation was developed by Kanai,5 You,6 and us7 independently (Scheme 1a). Subsequently, the copper-promoted cross dehydrogenative acyloxylation8 and arylation9 of unactivated sp3 C–H bonds were realized in our laboratory (Scheme 1b). However, the ligand directed copper-promoted dehydrogenative coupling of two sp3 C–H bonds remains a challenge.

Scheme 1. Copper-promoted dehydrogenative coupling of sp3 C–H bonds.

Based on the abovementioned studies, we envisaged that the site-selective dehydrogenative coupling of an unactivated sp3 C–H bond and another reactive sp3 C–H bond species, such as nitromethane,10 alkylnitriles,11 or carbonyl compounds,12 could be performed by copper catalysis with bidentate directing group assistance. Therefore, we carried out the reaction of a series of aliphatic amides bearing the 8-aminoquinoline directing group with nitromethane in the presence of copper catalysts. To our surprise, an unexpected carbonylated compound was obtained instead of the dehydrogenative coupling product (Scheme 1c).13 Herein, we report this unprecedented β-carbonylation of amides with nitromethane as the carbonyl source via the copper-promoted C–H bond activation and a subsequent Nef type reaction.14

Results and discussion

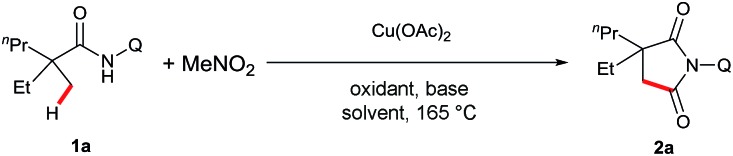

Our investigation commenced with 2-ethyl-2-methylpentanamide bearing a bidentate 8-aminoquinoline directing group (1a) as the model substrate (Table 1). Succinimide 2a was initially obtained in 8% yield in the presence of Cu(OAc)2 and K2HPO4 at 165 °C under air (entry 2). Encouraged by this result, we examined different solvents and found that iPrOH was a superior candidate (entry 6). Further investigation revealed that addition of an external single electron transfer oxidant can improve the yield, and K2S2O8 was proven to be the best pick (entries 9–11). Screening of bases showed that employing PhCO2Na as an additive, which was used in our previous report of intramolecular amidation, further increased the yield to 39% (entry 14). Mixed solvents were next surveyed, and a mixture of iPrOH and dioxane led to a better yield (entry 15). Interestingly, the addition of Al2O3 and DMPU15 finally gave the best results for this dehydrogenative carbonylation reaction (entry 17). The control experiments showed that no desired product was observed in the absence of MeNO2 or the copper catalyst (entries 18 and 19).

Table 1. Optimization of the sp3 C–H carbonylation a .

| ||||

| Entry | Oxidant | Base | Solvent | Yield b (%) |

| 1 | K2HPO4 | MeNO2 | 0 | |

| 2 | K2HPO4 | 1,4-Dioxane | 8 | |

| 3 | K2HPO4 | MeCN | Trace | |

| 4 | K2HPO4 | tBuOH | 11 | |

| 5 | K2HPO4 | tAmOH | 10 | |

| 6 | K2HPO4 | iPrOH | 14 | |

| 7 | O2 | K2HPO4 | iPrOH | Trace |

| 8 | AgOAc | K2HPO4 | iPrOH | Trace |

| 9 | (tBuO)2 | K2HPO4 | iPrOH | 18 |

| 10 | Na2S2O8 | K2HPO4 | iPrOH | 19 |

| 11 | K2S2O8 | K2HPO4 | iPrOH | 24 |

| 12 | K2S2O8 | Na2HPO4 | iPrOH | 26 |

| 13 | K2S2O8 | NaOAc | iPrOH | 31 |

| 14 | K2S2O8 | PhCO2Na | iPrOH | 39 |

| 15 | K2S2O8 | PhCO2Na | iPrOH/1,4-dioxane (0.45 : 0.55) | 54 |

| 16 c | K2S2O8 | PhCO2Na | iPrOH/1,4-dioxane (0.45 : 0.55) | 65 |

| 17 c , d | K2S2O8 | PhCO2Na | iPrOH/1,4-dioxane (0.45 : 0.55) | 71(68) |

| 18 c , d , e | K2S2O8 | PhCO2Na | iPrOH/1,4-dioxane (0.45 : 0.55) | 0 |

| 19 c , d , f | K2S2O8 | PhCO2Na | iPrOH/1,4-dioxane (0.45 : 0.55) | 0 |

aReaction conditions: 1a (0.3 mmol), Cu(OAc)2 (1 eq.), oxidant (2 eq.), base (1 eq.), solvent (2 mL), 165 °C, 24 h.

bYields are based on 1a, determined by 1H NMR using dibromomethane as the internal standard. Isolated yield is in parenthesis.

cAl2O3 (60 mg).

dDMPU (2 eq.).

eNo MeNO2.

fNo Cu(OAc)2.

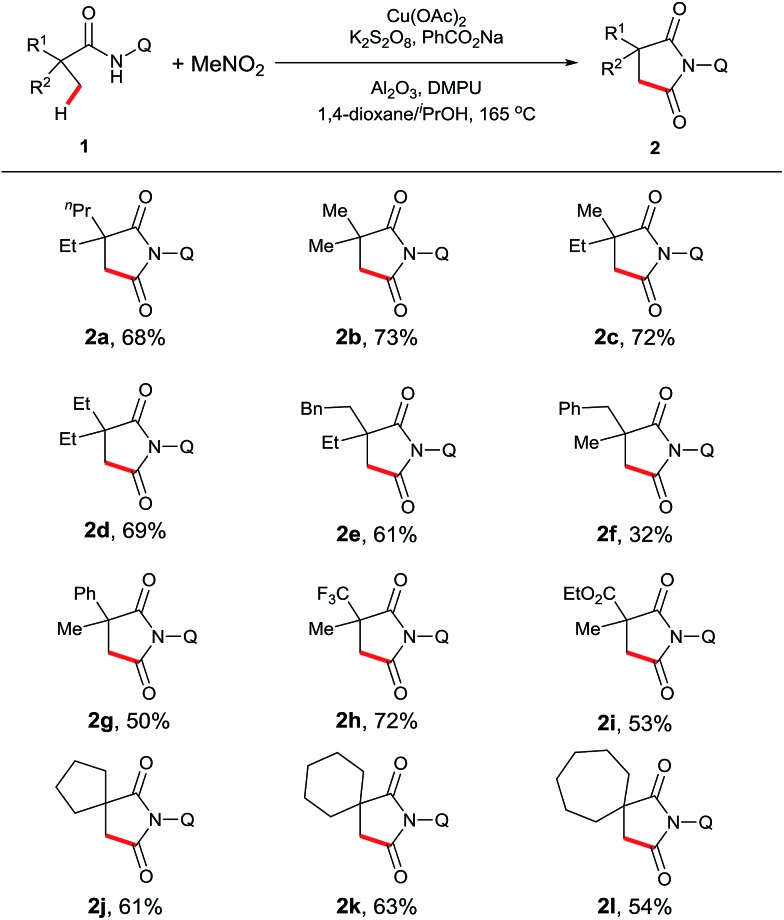

With the optimal conditions established, we examined the scope of aliphatic amide substrates (Scheme 2). Pivalamide proved to be an excellent substrate in this transformation, affording the carbonylation product in 73% yield (2b). Replacing the methyl group on the α-carbon with other alkyl groups, such as ethyl and propyl, gave the corresponding product in good yields (2c and 2d). When the α-carbon was substituted with a benzyl group, the carbonylation occurred exclusively on the carbon center of the methyl group, presumably due to a steric effect (2f). α-Phenyl amide could participate in the reaction to readily provide the desired product (2g). Furthermore, substrates containing trifluoromethyl (2h) or methoxycarbonyl groups (2i) on the α-carbon proved to be viable. It is worth noting that the starting material was recovered with N-(quinolin-8-yl)isobutyramide as the substrate under the standard conditions, indicating that a quaternary α-carbon is required for this reaction. In addition, the removability of the quinolyl moiety was previously demonstrated in our laboratory.13e

Scheme 2. Scope of sp3 C–H carbonylation. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.3 mmol), Cu(OAc)2 (0.3 mmol), K2S2O8 (0.6 mmol), PhCO2Na (0.15 mmol), Al2O3 (60 mg), DMPU (0.6 mmol), MeNO2 (1.0 mL), 1,4-dioxane (0.9 mL), iPrOH (1.1 mL), 165 °C, 24 h.

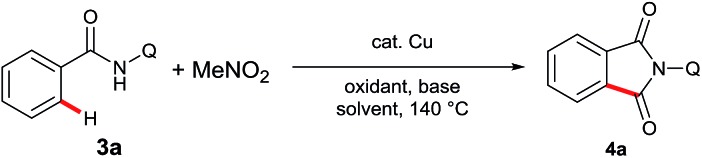

To further expand the scope of the substrates and broaden the synthetic utility of this reaction, we next investigated the carbonylation of sp2 C–H bonds (Table 2). To our delight, the reaction could be realized with a catalytic amount of Cu(OAc)2. The optimal results were acquired with 2 equivalents Ag2CO3 and 1 equivalent PhCO2Na in DMA at 140 °C (entry 8).

Table 2. Optimization of the sp2 C–H carbonylation a .

| |||||

| Entry | Cu source | Oxidant | Base | Solvent | Yield b (%) |

| 1 | Cu(OAc)2 | O2 | 1,4-Dioxane | 17 | |

| 2 | Cu(OAc)2 | MnO2 | 1,4-Dioxane | 28 | |

| 3 | Cu(OAc)2 | NMO | 1,4-Dioxane | 33 | |

| 4 | Cu(OAc)2 | Ag2O | 1,4-Dioxane | 19 | |

| 5 | Cu(OAc)2 | Ag2CO3 | 1,4-Dioxane | 45 | |

| 6 | Cu(OAc)2 | Ag2CO3 | DMA | 74 | |

| 7 | Cu(OAc)2 | Ag2CO3 | PhCO2Na | DMA | 69 |

| 8 | Cu(OAc)2 | Ag2CO3 | Py | DMA | 86 |

| 9 | Cu(OAc)2 | Ag2CO3 | Na2HPO4 | DMA | 90(86) |

| 10 | CuCl | Ag2CO3 | Na2HPO4 | DMA | 76 |

| 11 | — | Ag2CO3 | Na2HPO4 | DMA | 0 |

aReaction conditions: 3a (0.3 mmol), Cu(OAc)2 (10 mol%), oxidant (2 eq.), base (1 eq.), solvent (2 mL), 140 °C, 24 h.

bYields are based on 3a, determined by 1H NMR using dibromomethane as the internal standard. Isolated yield is in parenthesis.

Next, we examined the compatibility of the reaction with aromatic amide derivatives, which are summarized in Scheme 3. As expected, a wide range of functional groups including halogens were well tolerated under the optimized conditions. Substrates with electron-donating groups on the phenyl ring gave the desired products in good to excellent yields (4d, 4e, and 4f). Conversely, substrates containing halogen atoms afforded the phthalimides with slightly reduced yields (4g, 4h, 4i, and 4n). Electron-withdrawing group substituted aromatic amides also provided the corresponding carbonylation products in moderate yields (4j, 4k, and 4l). Furthermore, 1-naphthamide and 2-naphthamide derivatives reacted to produce good yields (4o and 4p).

Scheme 3. Scope of sp2 C–H carbonylation. Reaction conditions: 3 (0.3 mmol), Cu(OAc)2 (10 mol%), Ag2CO3 (2 eq.), Na2HPO4 (1 eq.), MeNO2 (0.5 mL), DMA (2 mL), 140 °C, 24 h. a165 °C, 48 h.

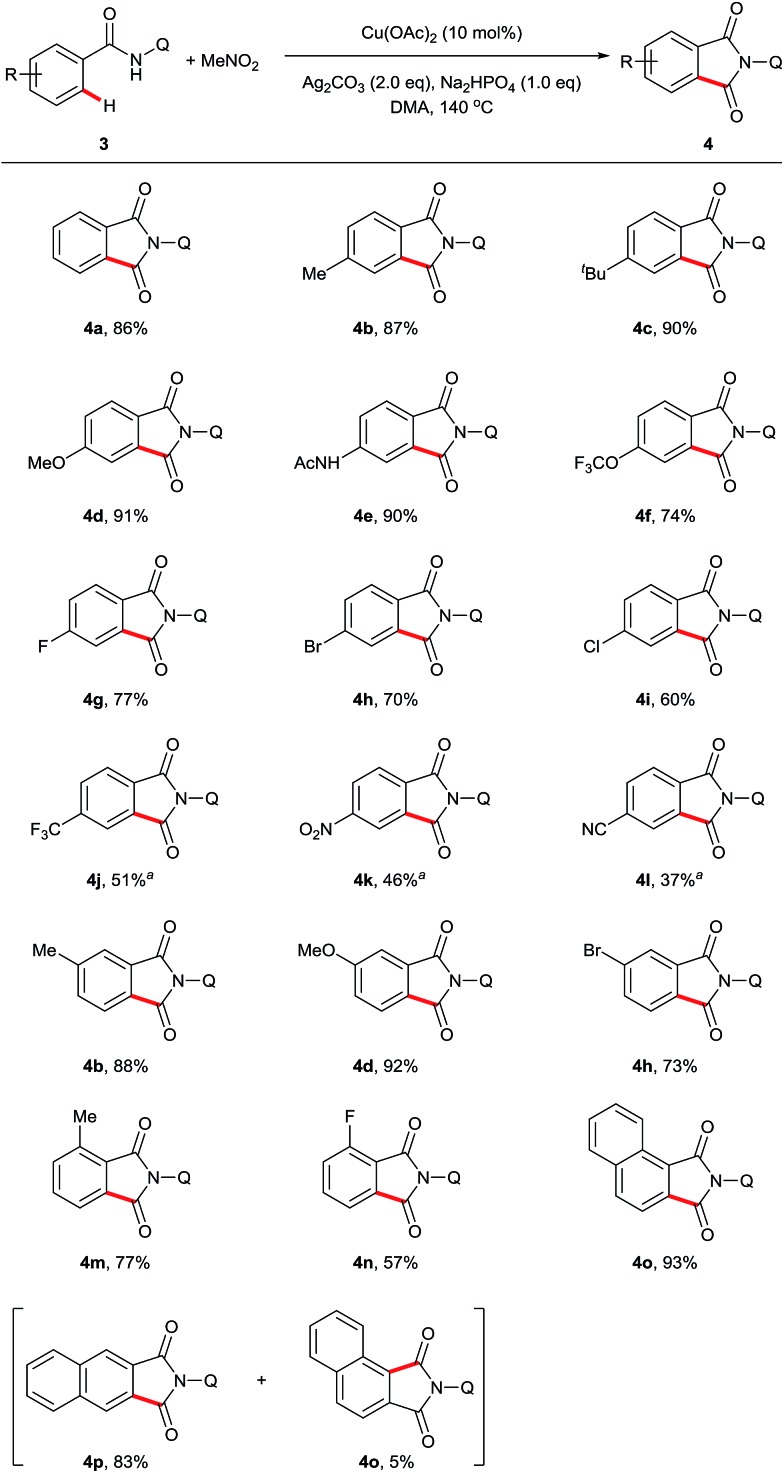

To gain some insights into this novel transformation mechanism, a series of deuterium-labelling experiments were performed. As shown in Scheme 4, evident H/D exchange of the substrate was found when the deuterium-labelled 2,2-diethyl-N-(quinolin-8-yl)pentanamide (D3-1d) was subjected to the standard conditions, indicating that the sp3 C–H bond cleavage is a reversible step. In addition, regular 2d was obtained in 92% yield from the subjection of [D/H]-2d to the current reaction system, suggesting that the keto–enol tautomerism might account for the fast H/D exchange of the product [D/H]-2d. In contrast, no apparent H/D exchange was observed when the deuterium-labelled N-(quinolin-8-yl)benzamide (D5-3a) was subjected to the standard conditions, indicating that the sp2 C–H bond cleavage is an irreversible step. Furthermore, a secondary kinetic isotope effect was observed for 3a based on the early relative rate of parallel reactions, indicating that the sp2 C–H cleavage of 3a should not be the rate-determining step. Finally, the addition of 4 equivalents of H218O to the reaction of 3a resulted in 60% of 18O incorporation into 4a, suggesting that water may be the source of oxygen in the carbonyl group.

Scheme 4. Kinetic isotope effect studies.

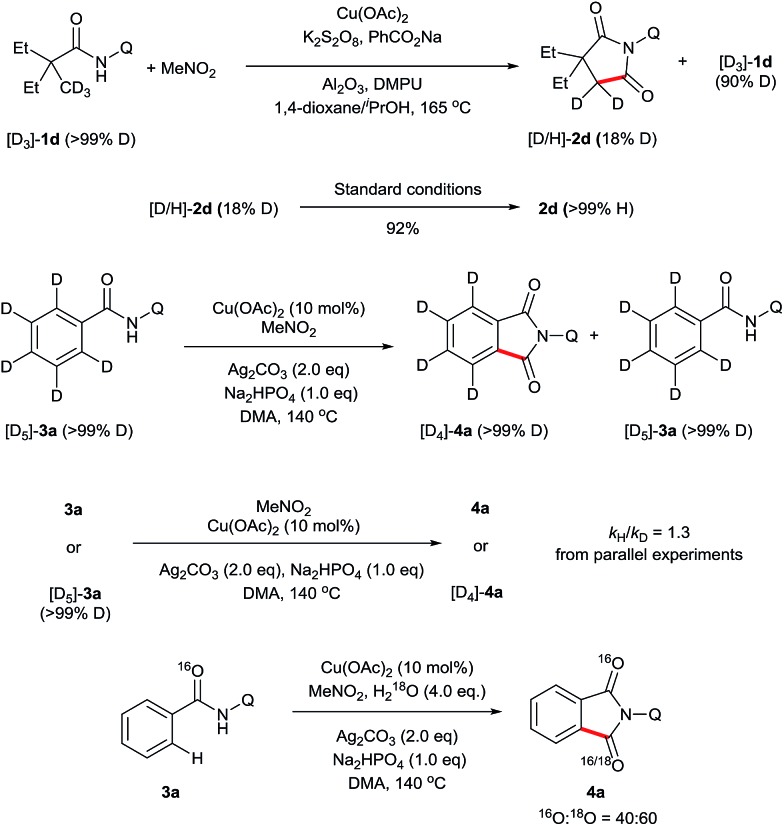

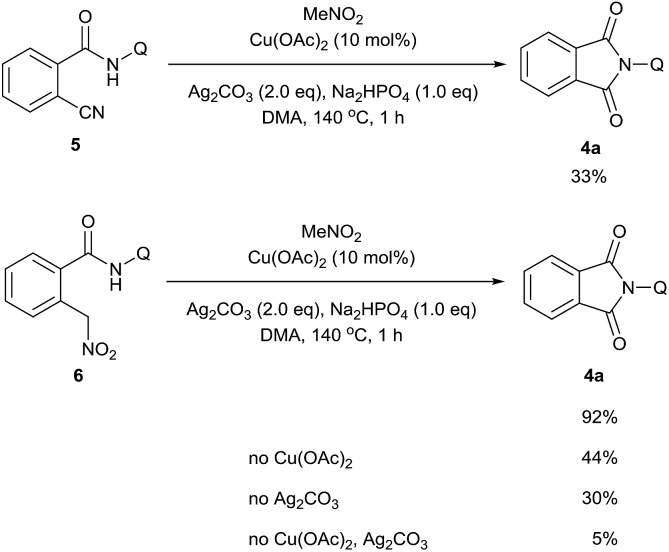

A series of control experiments were carried out to further probe the transformation pathway (Scheme 5). The cyano compound 5, a potential intermediate that was previously reported in the copper-catalyzed cyanation of 2-phenylpyridine with nitromethane10b was subjected to the reaction system and afforded the carbonylation product in 33% yield. On the other hand, the phthalimide product 4a was obtained in 92% yield from the originally proposed nitromethyl product 6, indicating that it is likely the major intermediate in this catalytic process. We then investigated the transformation from 6 to the product 4a with a number of control experiments. It was found that either Cu(OAc)2 or Ag2CO3 could promote the reaction, whereas only a small amount of product was formed without any metal. We thus infer that the metal salts should act as Lewis acid catalysts in this process.

Scheme 5. Control experiments.

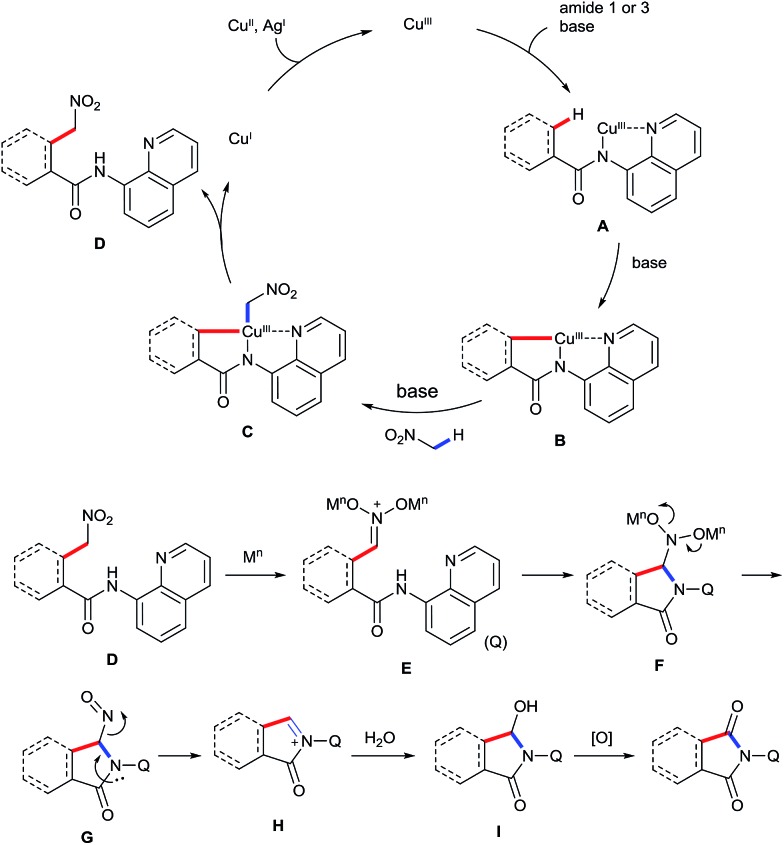

On the basis of the abovementioned results and previous reports,5–9,16 a plausible mechanism for the observed transformation is proposed and is depicted in Scheme 6. The reaction is believed to be initiated by coordinating the CuIII species to the bidentate ligand, followed by ligand exchange under basic conditions to generate intermediated A. Cyclometalation of A through a sp2 or sp3 C–H activation process affords intermediate B. Subsequently, ligand exchange of B with nitromethane in the presence of the base affords intermediate C, which undergoes reductive elimination to give the intermediate D. Formation of iminium ion E in the presence of a Lewis acid, followed by a sequence of the intramolecular addition and the loss of the nitroso group gives rise to the imine intermediate H. Finally, the addition of water and the subsequent oxidation provide the desired product.

Scheme 6. Plausible carbonylation reaction mechanism.

Conclusions

In summary, a novel copper-promoted site-selective carbonylation of sp2 or unactivated sp3 C–H bonds has been established using nitromethane as the carbonyl source with the assistance of an 8-aminoquinolyl auxiliary. Preliminary mechanistic experiments suggested that the substrate undergoes a dehydrogenative coupling with nitromethane, followed by a Nef type reaction to form the carbonylation product. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first example of unactivated C–H bond functionalization integrated with the Nef reaction. Further studies toward understanding the detailed mechanism and potential application of this transformation are in process.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and the NSF CHE-1350541 is greatly appreciated for this study. The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21332005, China) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (D-1361, USA) are also acknowledged.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures and characterization data. See DOI: 10.1039/c6sc01087c

References

- For selected recent reviews, see: ; (a) Daugulis O., Do H.-Q., Shabashov D. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:1074. doi: 10.1021/ar9000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen X., Engle K. M., Wang D.-H., Yu J.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:5094. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Davis H. M., Du Bois J., Yu J.-Q. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1855. doi: 10.1039/c1cs90010b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gutekunst W. R., Baran P. S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:1976. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wencel-Delord J., Droge T., Liu F., Glorius F. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:4740. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15083a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Cho S. H., Kim J. Y., Kwak J., Chang S. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011;40:5068. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15082k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) White M. C. Science. 2012;335:807. doi: 10.1126/science.1207661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Yamaguchi J., Yamaguchi A. D., Itami K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:8960. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Li J., De Sarkar S., Ackermann L. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2016;55:217. [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent reviews, see: ; (a) Colby D. A., Bergman R. G., Ellman J. A. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:624. doi: 10.1021/cr900005n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lyons T. W., Sanford M. S. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yeung C. S., Dong V. M. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1215. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wendlandt A. E., Suess A. M., Stahl S. S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:11062. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Rouquet G., Chatani N. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:11726. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kozhushkov S. I., Ackermann L. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:886. [Google Scholar]

- Kitahara M., Umeda N., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2160. doi: 10.1021/ja111401h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent reviews, see: ; (a) Miura M., Satoh T., Hirano K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2014;87:751. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hirano K., Miura M. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:10704. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34659a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hirano K., Miura M. Top. Catal. 2014;57:878. [Google Scholar]; (d) Dong J., Wu Q., You J., Tetrahedron Lett., 2015, 56 , 1591 , ; For examples, see: . [Google Scholar]; (e) Nishino M., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:6993. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Nishino M., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:4457. doi: 10.1002/anie.201300587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Odani R., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:11045. doi: 10.1021/jo402078q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Odani R., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:10784. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Odani R., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:2384. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Ni J., Kuninobu Y., Kanai M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:3496. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Yang Y., Qin D., He Z., You J.-S. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:8424. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Zhao Y., Zhang G., Ge H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:3706. doi: 10.1002/anie.201311263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Zhao Y., Ge H. Chem.–Asian J. 2014;9:2736. doi: 10.1002/asia.201402510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Zhao Y., Ge H. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:5978. doi: 10.1039/c5sc02143j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Vogl E. M., Buchwald S. L. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:106. doi: 10.1021/jo010953v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen X., Hao X.-S., Goodhue C. E., Yu J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6790. doi: 10.1021/ja061715q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Walvoord R. R., Berritt S., Kozlowski M. C. Org. Lett. 2012;14:4086. doi: 10.1021/ol301713j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Walvoord R. R., Kozlowski M. C. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:8859. doi: 10.1021/jo401249y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) VanGelder K. F., Kozlowski M. C. Org. Lett. 2015;17:5748. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Culkin D. A., Hartwig J. F. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:234. doi: 10.1021/ar0201106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bunescu A., Wang Q., Zhu J.-P. Chem.–Eur. J. 2014;20:14633. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chatalova-Sazepin C., Wang Q., Sammis G. M., Zhu J.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:5443. doi: 10.1002/anie.201412357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Bunescu A., Wang Q., Zhu J.-P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:3132. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Liu Y., Yang K., Ge H. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:2804. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04066c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent reviews, see: ; (a) Bellina F., Rossi R. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1082. doi: 10.1021/cr9000836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johansson C. C. C., Colacot T. J., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed., 2010, 49 , 676 , , For selected recent examples, see: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Zhu W., Zhang D., Yang N., Liu H. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:10634. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03837a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang H.-L., Shang M., Sun S.-Z., Zhou Z.-L., Laforteza B. N., Dai H.-X., Yu J.-Q. Org. Lett. 2015;17:1228. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For recent examples of C–H carbonylation, see: ; (a) Inoue S., Shiota H., Fukumoto Y., Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6898. doi: 10.1021/ja900046z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoo E. J., Wasa M., Yu J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17378. doi: 10.1021/ja108754f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wrigglesworth J. W., Cox B., Lloyd-Jones G. C., Booker-Milburn K. I. Org. Lett. 2011;13:5326. doi: 10.1021/ol202187h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Hasegawa N., Charra V., Inoue S., Fukumoto Y., Chatani N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:8070. doi: 10.1021/ja2001709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wu X., Zhao Y., Ge H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:4924. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noland W. E. Chem. Rev. 1955;55:137. [Google Scholar]

- For examples of using DMPU in C–H functionalization, see: ; (a) Chen Q., Ilies L., Nakamura E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:428. doi: 10.1021/ja1099853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ilies L., Chen Q., Zeng X.-M., Nakamura E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5221. doi: 10.1021/ja200645w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen Q., Ilies L., Yoshikai N., Nakamura E. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3232. doi: 10.1021/ol2011264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Tamelen E. E., Asd Thiede R. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:2615. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.