Abstract

Background:

Nalbuphine when used as adjuvant to hyperbaric bupivacaine has improved the quality of perioperative analgesia with fewer side effects. Fentanyl is a lipophilic opioid with a rapid onset following intrathecal injection. It does not cause respiratory depression and improves duration of sensory anesthesia without producing significant side effects.

Aim:

This study aims to compare the postoperative analgesia of intrathecal nalbuphine and fentanyl as adjuvants to bupivacaine in cesarean section.

Methodology:

A prospective, randomized, double-blind, and comparative study was conducted on 150 parturients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II of age group 20–45 years with normal coagulation profile undergoing cesarean section under spinal anesthesia. These patients were randomized into three groups with fifty patients in each group. Group I received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (10 mg) plus 0.4 ml nalbuphine (0.8 mg), Group II received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (10 mg) plus 0.4 ml fentanyl (20 μg), and Group III received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine (10 mg) plus 0.4 ml of normal saline.

Results:

The mean duration of effective analgesia was 259.20 ± 23.23 min in Group I, 232.70 ± 13.15 min in Group II, and 168.28 ± 7.55 min in Group III. The mean number of rescue analgesics required was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in Group I as compared to Group II and III.

Conclusion:

Both intrathecal nalbuphine 0.8 mg and fentanyl 20 μg are effective adjuvants to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine in subarachnoid block. However, intrathecal nalbuphine prolongs postoperative analgesia maximally and may be used as an alternative to intrathecal fentanyl in cesarean section.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, cesarean section, fentanyl, nalbuphine, subarachnoid block

INTRODUCTION

Subarachnoid block is the preferred anesthesia for cesarean section, being simple to perform and economical with rapid onset.[1]

Adding adjuvant drugs to intrathecal local anesthetics improves quality and duration of sensory blockade and prolongs postoperative analgesia. Intrathecal opioids are synergistic with local anesthetics, thereby intensifying the sensory block without increasing sympathetic block.[1]

Fentanyl is a lipophilic opioid with a rapid onset following intrathecal injection and does not migrate to the 4th ventricle to cause respiratory depression. Various studies have shown that it improves duration of sensory anesthesia and postoperative analgesia without producing significant side effects.[1,2]

Nalbuphine when used as adjuvant to hyperbaric bupivacaine has also improved the quality of perioperative analgesia with fewer side effects. It is a mixed synthetic agonist antagonist which attenuates the μ-opioid effects and enhances the κ-opioid effects.[3] There is no documented report of neurotoxicity with nalbuphine. Morphine, fentanyl, and other μ-opioids come under Narcotic Act, thus their availability is a major concern while nalbuphine is easily available and with fewer side effects.[4]

Culebras et al. compared intrathecal morphine (0.2 mg) with different doses of intrathecal nalbuphine (0.2, 0.8, 1.6 mg) in cesarean section and found that intrathecal nalbuphine 0.8 mg provides good intraoperative and early postoperative analgesia without side effects (no postoperative nausea and vomiting or pruritus). Nalbuphine 1.6 mg did not increase efficacy but increased the incidence of complications. Furthermore, the postoperative analgesia lasted significantly longer in the morphine group but was associated with side effects.[5]

Mukherjee et al. compared 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 mg of intrathecal nalbuphine in lower limb orthopedic surgery and recommended 0.4 mg of nalbuphine as the optimal dose without any side effects.[6]

Gomaa et al. compared intrathecal nalbuphine (0.8 mg) and intrathecal fentanyl (25 μg) as adjuvants to bupivacaine in sixty patients in cesarean section and concluded that both improved intraoperative analgesia and prolonged early postoperative analgesia in cesarean section.[7]

There are very few large studies that have compared intrathecal nalbuphine with intrathecal fentanyl added to hyperbaric bupivacaine in cesarean section. Therefore, we designed a randomized double-blind study to compare the effects of intrathecal nalbuphine and fentanyl as adjuvants to bupivacaine in comparison to plain bupivacaine in 150 patients undergoing cesarean section. The aim of this study was to compare fentanyl with nalbuphine as intrathecal adjuvant to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine in terms of sensory and motor blockade characteristics and duration of postoperative analgesia as the primary end points and intraoperative hemodynamic changes, sedation, pruritus, and respiratory depression as the secondary end points in patients undergoing cesarean section.

METHODOLOGY

After obtaining the hospital ethical committee approval and written informed consent, one hundred and fifty patients with ASA physical status Class I or II, aged 20–45 years, posted for cesarean section in our institution were included in this study. This was a prospective randomized double-blind comparative study. Patients with contraindication for spinal anesthesia were excluded from this study. The patients were randomized by computer-generated random numbers into three groups of fifty each.

Preanesthetic evaluation and basic laboratory investigations were done in all the patients, and they were explained in detail about the procedure of the spinal anesthesia during the preanesthetic visit. Patients were familiarized with the visual analog scale (VAS)[8] (0 – No pain, 10 – Worst pain) a day before surgery.

In the operating room, baseline blood pressure (BP) (systolic, diastolic, and mean), heart rate, respiratory rate, and peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) were recorded after attaching routine monitors (electrocardiogram, noninvasive BP, and pulse oximeter). Intravenous access was secured with 18G cannula, and all patients were preloaded with 10 ml/kg of Ringer's lactate solution. The study medication (2.4 ml of the drug solution) was prepared by the anesthesiologist who did not take part in the study. Group I patients received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine plus 0.4 ml nalbuphine (0.8 mg), Group II patients received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine plus 0.4 ml fentanyl (20 μg), and Group III patients received 2 ml of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine plus 0.4 ml of normal saline. The subarachnoid block was performed by the anesthesiologist who was not involved further in the study to ensure blinding. Both patients and observers were blinded to the drugs given. Patients were then immediately placed in the supine position, with a wedge under the right hip to maintain left uterine displacement. Oxygen was provided through Venturi mask at the rate of 4 l/min.

BP (systolic, diastolic, and mean), heart rate, respiratory rate, and SpO2 were continuously monitored and recorded at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min after the injection, and subsequently every 15 min. Hypotension (defined as systolic BP of <90 mmHg or <20% of baseline BP) was treated with intravenous fluid initially (250 ml boluses repeated twice) and intravenous ephedrine 5 mg, if required. Bradycardia (defined as heart rate of <60) was treated with 0.6 mg of intravenous atropine sulfate.

Sensory block was assessed by pinprick method and motor block by Modified Bromage Scale.[9] The onset of sensory blockade (defined as the time from the injection of intrathecal drug to the absence of pain at the T6 dermatome) and onset of complete motor blockade (time taken from the injection to development of Bromage's Grade 3 motor block) were recorded. The duration of sensory blockade (two segment regression from highest level of sensory blockade) was also recorded in each patient. Duration of motor blockade (time required for motor blockade to return to Bromage's Grade 1 from the time of onset of motor blockade) was also noted. Grades of sedation during surgery were assessed by the Modified Ramsay's sedation scale.[10]

Postoperatively, pain score (VAS) was assessed 1 h for first 4 h and at 12 and 24 h. The duration of effective analgesia (time from the intrathecal injection to the first rescue analgesic requirement, VAS score >3) was noted. Intramuscular diclofenac (75 mg) was administered as rescue analgesic, and total number of rescue analgesics required postoperatively in 24 h period was recorded. Patients were also assessed for side effects such as nausea, vomiting, hypotension, pruritis, and bradycardia.

Statistical analysis was done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Taking alpha error of probability as 0.05 and power of study as 80%, minimum required sample size was estimated to be 42 in each group. Level of significance was ascertained by chi square, Kruskal-Wallis test and Mann Whitney U test. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant and P < 0.001 was considered highly significant

RESULTS

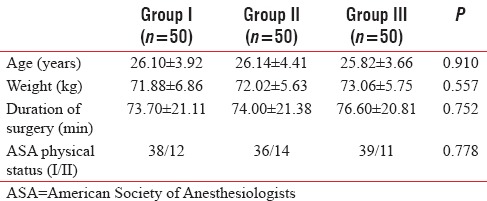

As shown in Table 1, all the three groups were comparable with respect to age, weight, ASA physical status, and duration of surgery.

Table 1.

Demographic profile

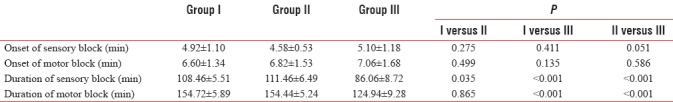

As shown in Table 2, the difference in the time of onset of sensory and motor block was statistically nonsignificant (NS) among the groups (P > 0.05). The mean duration of sensory block was 108.46 ± 5.51 min in Group I, 111.46 ± 6.49 min in Group II, and 86.06 ± 8.72 min in Group III. The mean duration of sensory block was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in patients receiving nalbuphine and fentanyl as compared to Group III [Table 2]. The mean duration of motor block (time required for motor block to return to Bromage's Grade 1 from the time of onset of motor block) was 154.72 ± 5.89 min in Group I, 154.44 ± 5.24 min in Group II, and 124.94 ± 9.28 min in Group III. The mean duration of motor block was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in Group I and II patients than in Group III [Table 2].

Table 2.

Characteristics of sensory and motor block

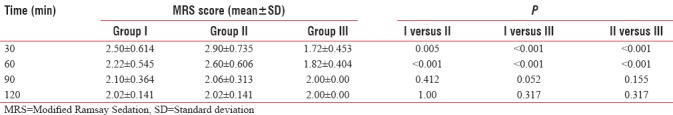

The Modified Ramsay sedation score was recorded at 30 min interval from subarachnoid injection till 120 min [Table 3]. Modified Ramsay sedation score was significantly higher in Group II as compared to Group I and III at 30 and 60 min.

Table 3.

Modified Ramsay sedation score

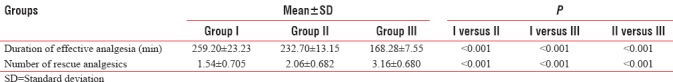

As shown in Table 4, the mean duration of effective analgesia was 259.20 ± 23.23 min in Group I, 232.70 ± 13.15 min in Group II, and 168.28 ± 7.55 min in Group III. The difference was statistically highly significant (P < 0.001) in the three groups with mean duration highest in Group I and lowest in Group III.

Table 4.

Postoperative analgesia

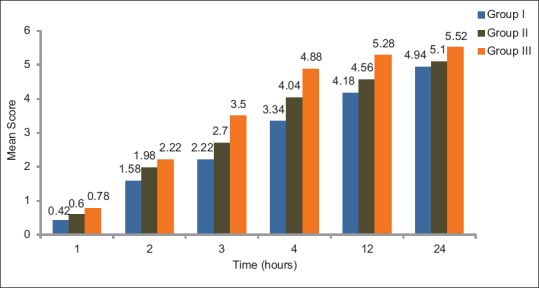

Postoperatively, VAS score was seen at 1 h interval up to 4 h, at 12 and 24 h [Figure 1]. The mean VAS score was signifi cantly lower in Group I and II as compared to Group III (P < 0.05). The mean number of rescue analgesics required was 1.54 ± 0.705 in Group I, 2.06 ± 0.682 in Group II, and 3.16 ± 0.680 in Group III. The mean number of rescue analgesics required was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in Group I as compared to Group II and III [Table 4].

Figure 1.

Postoperative visual analogue scale score

DISCUSSION

We conducted a randomized double-blind study to compare intrathecal nalbuphine and fentanyl as adjuvants to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with bupivacaine alone in patients undergoing cesarean section.

Nalbuphine exhibits a ceiling effect to analgesia, i.e. increase in dose increases analgesic effect only up to a certain point beyond which there is no further enhancement of analgesia with the increase in dose.[11] We chose 0.8 mg of nalbuphine to compare with 20 μg of fentanyl as Culebras et al.[5] and Jyothi et al.[12] had previously observed that increasing nalbuphine dose from 0.8 to 1.6 mg and 2.4 mg did not increase analgesic efficacy.

We found that onset of sensory block was comparable in the three groups. Gomaa et al. compared intrathecal nalbuphine 0.8 mg and fentanyl 25 μg and found that there was no statistically significant difference in onset of sensory block between fentanyl (1.64 min) and nalbuphine (1.60 min) group.[7] Similar results were observed by Gupta et al.,[13] Ahmed et al.,[14] and Naaz et al.[11] However, Venkata et al. observed significantly faster onset of sensory block with fentanyl as adjuvant.[15]

The increase in the duration of sensory block in Group I and II was statistically significant in our study. Choi et al.,[16] Ahmed et al.,[14] Naaz et al.,[11] and Kumaresan et al.[17] showed similar results. Prolonged duration of sensory block with fentanyl had been observed in many studies.[18,19,20]

There was no statistically significant difference in the onset of motor block in the three groups. Similar results were obtained by Hunt et al.[21] and Tiwari et al.[22] However, Gomaa et al. found significantly rapid onset of motor block in patients given fentanyl (5.57 min) than in patients given nalbuphine (5.72 min) in cesarean section.[7]

The duration of motor block was comparable in patients who received nalbuphine and fentanyl, which was significantly longer than in patients who received bupivacaine alone. Our results were comparable with results of Gomaa et al.[7] and Bisht and Rashmi[23] However, Tilkar et al. observed no significant difference in duration of motor block between fentanyl and control group in orthopedic procedure.[24]

There was statistical difference in the Modified Ramsay sedation score in the three groups at 30 and 60 min with significantly higher sedation score in the fentanyl group. At 90 and 120 min, the three groups were comparable with regard to sedation. However, all the patients were arousable, and there was no incidence of respiratory depression. Results of Cowan et al. were comparable to our study.[25] Cowan et al. observed increased sedation with intrathecal fentanyl (20 μg) when compared with diamorphine (300 μg) and control. Gupta et al. showed comparable sedation scores with intrathecal fentanyl (25 μg) and nalbuphine (2 mg).[13]

The difference in mean duration of effective analgesia was statistically significant in the three groups when compared with each other, maximal in Group I followed by Group II and III. Our results were comparable to Jyothi et al.[12] Jyothi et al. conducted a study in 100 patients allocated to four groups: A, B, C, and D given 0.5 ml NS and 0.8, 1.6, and 2.5 mg nalbuphine, respectively, and found that nalbuphine significantly prolonged duration for first request of analgesia (322.4, 319.4, 317.8 min in Group B, C, and D) as compared to control group (190.4 min in Group A). Pain management in early postoperative period is one of the major concerns in perioperative care improving the overall outcome. Uncontrolled postoperative pain may produce a range of detrimental acute and chronic effects. The attenuation of perioperative pathophysiology that occurs during surgery through reduction of nociceptive input to central nervous system and optimization of perioperative analgesia may decrease complications and facilitate recovery during the immediate postoperative period.[26]

The mean VAS score for postoperative pain was lower in Group I as compared to Group II and III at all times. Patients who received intrathecal nalbuphine required significantly lesser number of rescue analgesics than Group II and III. Furthermore, the patients in fentanyl group required significantly lesser analgesia than the patients in Group III. Similar results were obtained by Naaz et al. and Mostafa et al.[11,27]

The three groups were comparable with regard to BP (mean, systolic, and diastolic), heart rate, respiratory rate, and SpO2. Intrathecal opioids are synergistic with local anesthetics and intensify the sensory block without increasing the sympathetic block. Our results are in accordance with Gomaa et al.[7] who observed no significant difference in hemodynamic variables in the study groups. The various side effects following administration of spinal anesthesia such as pruritus, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention, bradycardia, and hypotension were comparable in all the groups. Various studies have shown that incidence of adverse effects was not increased with nalbuphine or fentanyl.[13,14]

The effective relief of pain during the intra- and postoperative period is of principal importance for anesthesiologist as it has significant physiological benefit by means of smoother postoperative course and earlier discharge from hospital, and it may also reduce the onset of chronic pain syndromes. Nalbuphine, apart from its potent analgesic property, shows antagonizing morphine-induced side effects. Hence, it might be particularly considered, especially if the patient has history of μ side effects.

CONCLUSION

We conclude that both intrathecal nalbuphine 0.8 mg and intrathecal fentanyl 20 μg are effective adjuvants to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine in patients undergoing cesarean section under subarachnoid block. They increase the duration of sensory block as well as postoperative analgesia without any increase in side effects. However, intrathecal nalbuphine prolongs postoperative analgesia maximally and may be used as an alternative to intrathecal fentanyl in cesarean section.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bogra J, Arora N, Srivastava P. Synergistic effect of intrathecal fentanyl and bupivacaine in spinal anesthesia for cesarean section. BMC Anesthesiol. 2005;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu CC, Shu SS, Lin SM, Chu NW, Leu YK, Tsai SK, et al. The effect of intrathecal bupivacaine with combined fentanyl in cesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 1995;33:149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmauss C, Doherty C, Yaksh TL. The analgetic effects of an intrathecally administered partial opiate agonist, nalbuphine hydrochloride. Eur J Pharmacol. 1982;86:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(82)90389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin ML. The analgesic effect of subarachnoid administration of tetracaine combined with low dose morphine or nalbuphine for spinal anesthesia. Ma Zui Xue Za Zhi. 1992;30:101–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Culebras X, Gaggero G, Zatloukal J, Kern C, Marti RA. Advantages of intrathecal nalbuphine, compared with intrathecal morphine, after cesarean delivery: An evaluation of postoperative analgesia and adverse effects. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:601–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200009000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukherjee A, Pal A, Agrawal J, Mehrotra A, Dawar N. Intrathecal nalbuphine as an adjunct to subarachnoid block: What is the most effective dose? Anesth Essays Res. 2011;5:171–5. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.94759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomaa HM, Mohamed NN, Zoheir HA, Ali MS. A comparison between post-operative analgesia after intrathecal nalbuphine with bupivacaine and intrathecal fentanyl with bupivacaine after caesarean section. Egypt J Anaesth. 2014;30:405–10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeLoach LJ, Higgins MS, Caplan AB, Stiff JL. The visual analog scale in the immediate postoperative period: Intrasubject variability and correlation with a numeric scale. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:102–6. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199801000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bromage PR. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1978. Epidural Analgesia; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J. 1974;2:656–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5920.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naaz S, Shukla U, Srivastava S, Ozair E, Asghar A. A comparative study of analgesic effect of intrathecal nalbuphine and fentanyl as adjuvant in lower limb orthopaedic surgery. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:UC25–8. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/24385.10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jyothi B, Gowda S, Shaikh SI. A comparison of analgesic effect of different doses of intrathecal nalbuphine hydrochloride with bupivacaine and bupivacaine alone for lower abdominal and orthopedic surgeries. Indian J Pain. 2014;28:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta K, Rastogi B, Gupta PK, Singh I, Bansal M, Tyagi V. Intrathecal nalbuphine versus intrathecal fentanyl as adjuvant to 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine for orthopedic surgery of lower limbs under subarachnoid block: A comparative evaluation. Indian J Pain. 2016;30:90–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed F, Narula H, Khandelwal M, Dutta D. A comparative study of three different doses of nalbuphine as an adjuvant to intrathecal bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in abdominal hysterectomy. Indian J Pain. 2016;30:23–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkata HG, Pasupuleti S, Pabba UG, Porika S, Talari G. A randomized controlled prospective study comparing a low dose bupivacaine and fentanyl mixture to a conventional dose of hyperbaric bupivacaine for cesarean section. Saudi J Anaesth. 2015;9:122–7. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.152827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi DH, Ahn HJ, Kim MH. Bupivacaine-sparing effect of fentanyl in spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2000;25:240–5. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(00)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumaresan S, Raj AA. Intrathecal nalbuphine as an adjuvant to spinal anaesthesia: What is most optimum dose? Int J Sci Stud. 2017;5:57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biswas BN, Rudra A, Bose BK, Nath S, Chakrabarty S, Bhattacharjee S. Intrathecal fentanyl with hyperbaric bupivacaine improves analgesia during caesarean delivery and in early post-operative period. Indian J Anaesth. 2002;46:469–72. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh H, Yang J, Thornton K, Giesecke AH. Intrathecal fentanyl prolongs sensory bupivacaine spinal block. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:987–91. doi: 10.1007/BF03011070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bidikar M, Mudakanagoudar MS, Santhosh MC. Comparison of intrathecal levobupivacaine and levobupivacaine plus fentanyl for cesarean section. Anesth Essays Res. 2017;11:495–8. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_16_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunt CO, Naulty JS, Bader AM, et al. Analgesia with subarachnoid fentanyl-bupivacaine for caesarean delivery. Anaesthesiology. 1989;71:535–40. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198910000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tiwari AK, Tomar GS, Agrawal J. Intrathecal bupivacaine in comparison with a combination of nalbuphine and bupivacaine for subarachnoid block: A randomized prospective double-blind clinical study. Am J Ther. 2013;20:592–5. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31822048db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bisht S, Rashmi D. Comparison of intrathecal fentanyl and nalbuphine: A prospective randomized controlled study in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2017;21:194–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilkar Y, Bansal SA, Agnihotri GS. A comparative study of intrathecal clonidine and fentanyl as adjuvants to bupivacaine in lower limb orthopedic surgery. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2015;4:458–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cowan CM, Kendall JB, Barclay PM, Wilkes RG. Comparison of intrathecal fentanyl and diamorphine in addition to bupivacaine for caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:452–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kehlet H, Holte K. Effect of post operative analgesia on surgical outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:62–72. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mostafa MG, Mohamad MF, Farrag WS. Which has greater analgesic effect: Intrathecal nalbuphine or intrathecal tramadol? J Am Sci. 2011;7:480–4. [Google Scholar]