Abstract

Background:

Intrathecal morphine is commonly used for postcesarean analgesia. Its use is frequently associated with opioid-induced nausea, vomiting, and pruritus. Palonosetron (0.075 mg) combined with dexamethasone (8 mg) is postulated to have an additive effect over each drug alone. The study, therefore, compared the effect of intravenous (i.v.) palonosetron, dexamethasone, and palonosetron with dexamethasone combination in preventing intrathecal morphine-induced postoperative vomiting and pruritus in lower segment cesarean section (LSCS) patients.

Settings and Design:

Randomized, prospective, double-blinded, observational clinical study.

Methods:

Ninety pregnant women, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status class I undergoing LSCS were included in the study. They were randomly assigned to three groups – Group P received 0.075 mg palonosetron i.v., Group D received dexamethasone 8 mg i.v., and Group PD received palonosetron 0.075 mg along with dexamethasone 4 mg i.v., just after spinal anesthesia with bupivacaine 2.2 ml (12 mg) and 150 μg morphine. The incidence of pruritus, nausea, vomiting, and need for rescue drug were recorded for 24 h.

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test for categorical variables and Chi-square test for noncategorical variables.

Results:

The incidence of nausea, vomiting was significantly more in Group D (40%) than Group P (27%) and Group PD (20%) in 24 h. The incidence of pruritus was significantly more in Group D (6%) than Group P and PD (3%). The need of rescue antiemetic was more in Group D (30%) than Group P (6%) and Group PD (3%). No difference in three groups requiring rescue antipruritic drug.

Conclusion:

Prevention of intrathecal morphine-induced vomiting and pruritus was more effective with palonosetron alone or with dexamethasone combination than dexamethasone alone. Combination of palonosetron and dexamethasone proved no better than palonosetron alone.

Keywords: Dexamethasone, intrathecal morphine, palonosetron, postoperative nausea, vomiting and pruritus

INTRODUCTION

Neuraxial injection of opioids provides effective analgesia in many types of surgery. To make patient pain-free, early ambulatory and for better neonatal care usually, intrathecal morphine is used for the lower segment cesarean section (LSCS). However, spinal opioids are associated with a wide variety of side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and pruritus.[1] The incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients with an intrathecal opiate is 60%–80%.[2] The reported incidence of intrathecal opioid-induced pruritus is 20%–100%, more in postpartum cases.[3] Although the prophylactic and therapeutic effects of several antiemetic and antipruritic drugs have been studied extensively, preventing PONV and pruritis after intrathecal opioids remains still a major challenge.

Risk factors of PONV are many including patient factors (age, female gender, and obesity); surgery-related factors (middle ear, abdominal, and laparoscopic surgery); anesthesia-related factors (use of volatiles, opioids, and N2O) and other factors such as prior history of motion sickness, nonsmoking state, anxiety, postoperative pain, and early oral intake. Above study included female patients of the almost equal age group who received neuraxial morphine for cesarean section. Hence, all patients' characteristics and risk factors are similar in three groups.

5 hydroxytryptamine 3 (5HT3) receptor antagonist is widely used as the first line therapeutic agent for prevention of PONV and pruritus with good efficacy and minimal side effect.[4] Palonosetron, a newer 5HT3 antagonist, has a unique mechanism different from older agents with more potency and persistent effects. In contrast to the older 5HT3 antagonist, palonosetron's allosteric binding and positive cooperation triggers receptor internalization, which results in persistent inhibition of 5HT3 receptor function and long duration of action.[5] Studies have proved palonosetron to be a better antiemetic than ondansetron.

Dexamethasone is also one of the commonly used drugs for prevention of PONV. In 120 patients who received epidural morphine 3 mg for postcesarean delivery analgesia, dexamethasone 8 mg significantly decreased the incidence of PONV compared to placebo.[6] The efficacy of dexamethasone as an antipruritic drug after intrathecal opioid has not been studied.

It is recommended that patients at high risk of developing PONV should receive a combination of two or more different classes of antiemetic agents rather than a single drug because none of the available antiemetic is entirely effective in preventing PONV.[7]

It has been demonstrated that 5HT3 receptor antagonist (ondansetron, ramosetron) with dexamethasone is more effective in preventing PONV than ondansetron, ramosetron or dexamethasone alone.[8,9,10,11] All these studies included patients groups receiving intravenous (i.v.) patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with opioids, but Szarvas et al. studied this drug combination in patients receiving intrathecal morphine and did not find any benefit of ondansetron and dexamethasone combination over ondansetron alone.[12]

Recently, it was reported that combination of palonosetron and dexamethasone is more effective than palonosetron alone for prevention of PONV.[13,14] Studies by Bala et al. also prove the same, but all these studies were carried out on patients who underwent general anesthesia (GA).[15] None of the studies included patient groups who have intrathecal morphine as a risk factor of PONV. Data related to the efficacy of above drug combination in LSCS patients receiving intrathecal morphine is lacking.

Hence, the purpose of the study was to assess whether combination therapy using palonosetron and dexamethasone is more effective in preventing PONV and pruritus than monotherapy with palonosetron or dexamethasone in women receiving intrathecal morphine for LSCS.

METHODS

After obtaining the Institutional Ethical Committee approval and written informed consent from each patient, we studied 90 adult female American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status class I who were to undergo LSCS during the period of 1 year (October 2016–August 2017). Patients with systemic diseases, mothers having compromised fetus, contraindication to regional anesthesia, pregnancy-related complication such as eclampsia and acute obstetric hemorrhage, smokers, need of GA due to the failure of regional anesthesia, history of motion sickness and pruritic skin disease, on steroid medication, hypersensitivity to study drugs were excluded from the study.

Patients were allocated using computer-generated random numbers to receive one of the 3 treatments regimes. Group P received palonosetron 0.075 mg, Group D received dexamethasone 8 mg and Group PD received palonosetron 0.075 mg and dexamethasone 4 mg single dose. Patients, anesthesiologists involved and investigators, who collected postoperative data, were unaware of group allocation. In operation theater, all patients were given a 18G i.v. cannula and Ringer's lactate 500 ml was given as preloading. All standard monitors such as pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure, electrocardiography leads were attached. Under all aseptic measure, lumbar puncture was done in left lateral position with 25G spinal needle through a midline approach in L2–L3/L3–L4 interspace. Anesthesia was established with a single bolus dose of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine 2.2 ml and 150 μg morphine. The study drug was given slowly i.v. immediately after SA. All study drugs were diluted to 5 ml with NS by O. T technician and anesthesiologist delivering anesthesia was unaware of the drug composition. Midazolam 1–2 mg i.v. given for intraoperative sedation after baby delivery. Supplemental oxygen at 4–6 L/min through a venturi mask was given.

Postoperatively, all patients were shifted to the recovery room. Injection diclofenac aq. 75 mg i.v. given as rescue analgesic. Nausea was defined as an unpleasant sensation associated with awareness of the urge to vomit. Vomiting was defined as the forceful expulsion of gastric contents from the mouth and pruritus was defined as the sensation that provokes the desire to scratch. Failure of PONV prophylaxis was defined as any episode of nausea or vomiting requiring rescue antiemetic. Failure of pruritic prophylaxis was defined as any episode of itching that provokes the desire to scratch or use of rescue antipruritic. Injection metoclopramide was given for rescue treatment of PONV and injection naloxone for pruritus, respectively. PONV and pruritus were assessed at 30 min, 2, 4, 8, 16, and 24 h after surgery by an investigator. The PONV scoring was 0 = no nausea or vomiting; 1 = nausea; 2 = retching; 3 = vomiting. Pruritus score was 0 = no pruritus; 1 = mild pruritus; and 2 = severe pruritus requiring treatment.

Statistical analysis

Demographic variables were compared using Student's t-test. Chi-square test was done for noncategorical variables. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, numbers or percentages. SPSS for windows version 20 (IBM) was used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

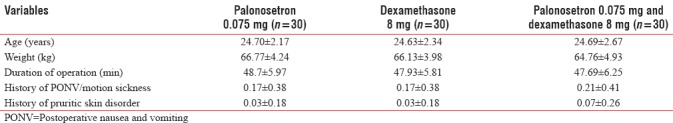

A total of 120 patients screened and 90 among them were randomized into three groups. The three groups were similar in terms of age, weight, the intrathecal opioid dose used, history of PONV, motion sickness and pruritic skin disease, and duration of operation [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

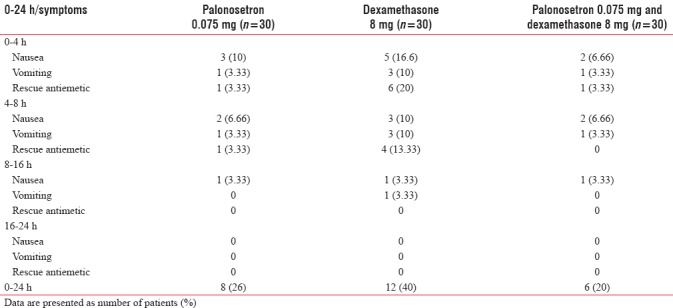

The proportion of PONV in the first 24 h postoperative period was 8 (26.6%) in the Group P, 12 (40%) in Group D and 6 (20%) in Group PD. On comparing the P value between Group P and palonosetron-dexamethasone, the difference was insignificant. Use of rescue antiemetic was more in Group D than Group P palonosetron-dexamethasone. The incidence of failure of PONV prophylaxis was more in three groups during the first 4 h. For first 16 h, nausea and vomiting was more in dexamethasone group than Group P and Group PD [Table 2]. However, after 16 h, there was no significant difference between three groups. The need of rescue antiemetic was more in Group D (30%) than Group P (6%) and Group PD (3%).

Table 2.

Proportion of patients who had nausea, vomiting, and need for rescue drug

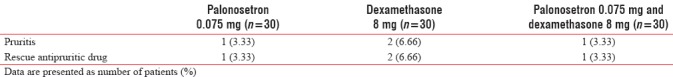

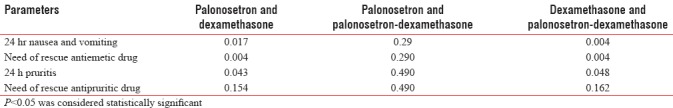

The incidence of pruritus for 24 h of surgery was 1 (3%), 2 (6%), and 1 (3%) in Group P, dexamethasone and palonosetron-dexamethasone, respectively [Table 3]. There was no statistically significant difference in need of rescue antipruritic drug between three groups [Table 4]. There is no statistically significant difference in the incidence of vomiting and rescue antiemetic drug requirement between group P and group PD(P>0.05) [Table 4].

Table 3.

Proportion of patients having pruritus and use of antipruritic drug

Table 4.

P value between different groups

DISCUSSION

The pathophysiology of PONV is complicated, and several kind of receptors and their mediators have been implicated in PONV. (1) Serotonin type 3 (5HT 3 receptor), (2) dopamine type 2 receptor, (3) histamine type 1 receptor, (4) muscarinic cholinergic type 1 receptor, (5) steroid receptor and (6) neurokinin type 1 (NK1) receptor. Based on these findings, modern PONV prophylaxis adopts the principle of a multimodal approach to treat high-risk patients with at least 2 or 3 different kind of receptor antagonists, rather than increasing dosage of one single receptor antagonist.[16]

Historical data indicate 60%–80% of patients who receives no antiemetic prophylaxis after undergoing cesarean section proceeding with neuraxial opioids have PONV. Even though new antiemetic drugs have been introduced, there are no agents that can completely prevent or treat PONV due to multifactorial etiology and various receptor sites involved in PONV. Therefore, in patients at high risk for PONV, it is recommended that combination therapy using several antiemetics targeting different receptor sites be employed rather than using a single antiemetic agent.[7]

Above study included female patients who received neuraxial morphine for cesarean section. All patients' characteristics and risk factors were similar in three groups as concluded from Table 1. In this study, combination of palonosetron 0.075 mg and dexamethasone 8 mg was compared with either drug alone during the first 24 h after surgery. Several drug combinations have been studied. Selective 5HT3 antagonists have been extensively studied so far and are currently primary therapy for PONV prevention because they have fewer side effects, such as sedation or extrapyramidal symptoms as compared with other antiemetics. First generation 5HT3 antagonists such as ondansetron, dolasetron, tropisetron, granisetron, and ramosetron exert an effect through competitive binding at 5HT3 receptor site which antagonises the effect of serotonin centrally and peripherally.[7]

Palonosetron is a second generation 5HT3 antagonist that has a high affinity for the 5HT3 receptor and longer plasma half-life (exceeding 40 h) than older antagonists (5–12 h) which results in prolonged inhibition of receptor function.[17,18] Following characteristics distinguishes palonosetron from first generation antagonists. The first palonosetron differs in chemical structure. It is a fused tricyclic ring system attached to a quinuclidine moiety unlike older drugs who are three substituted indole structure resembling serotonin. Second, palonosetron exhibits allosteric binding and positive cooperativity when binding to the 5HT3 receptor, triggering receptor internalization resulting in prolonged inhibition of receptor function.[19] Third, palonosetron also inhibits responses induced by substance P, the dominant mediator of delayed emesis after chemotherapy through differential inhibition of 5HT3/NK1 receptor crosstalk.[20]

These pharmacologic characteristics of palonosetron could decrease the need for combination therapy generally required for PONV prophylaxis in high-risk patients. Kovac et al. showed that palonosetron 0.075 mg effectively reduced PONV up to 72 h after an operation compared to placebo.[21] It was a dose – ranging study, and they found 0.075 mg dose of palonosetron was an effective dose. In addition, palonosetron 0.075 mg was more effective than ondansetron 4 mg and ramosetron 0.3 mg in the prevention of PONV during first 48 h after lap surgery in high-risk women receiving fentanyl-based i.v. PCA.[22]

Dexamethasone has been postulated to be an effective antiemetic after pediatric and general surgery.[23,24] It has also been suggested that dexamethasone decreases the incidence of PONV after neuraxial opioid.[25] In a study with 120 parturients who received epidural morphine (3 mg), dexamethasone 8 mg iv significantly decreased the incidence of PONV compared with placebo (18% and 51%, respectively).[6] Although the exact mechanism for dexamethasone antiemetic effect is not well-known, it may exert central antiemetic action mainly through activation of glucocorticoid receptors in the nucleus of solitary tract, the nucleus of raphe and the area postrema. A meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of dexamethasone in reducing PONV showed that a single i.v. dose of dexamethasone 5–10 mg was effective in reducing PONV in women receiving neuraxial morphine for cesarean delivery or abdominal hysterectomy.[26]

However, in the present study group receiving dexamethasone monotherapy had 40% incidence of PONV as compared to other two groups where the incidence was 26% in Group P and 20% in Group PD. This would suggest a lack of efficacy of dexamethasone in preventing PONV in postcesarean patients who had received neuraxial morphine. This difference between our study and above study concludes that PONV produced by higher doses of morphine as used epidurally can be more readily reversed by dexamethasone than can PONV after an intrathecal dose. Moreover, PONV usually occurs during first 6 h after intrathecal morphine but 6–24 h after epidural morphine; whereas dexamethasone has a biological half-life of 36–72 h proving its better control of chemorelated delayed emesis (beyond 24 h) as compared to classic antiemetics.[27,28,29,30] A study by Jadon et al. noted a lag period of 4 h before dexamethasone effect could be observed.[31] Hence, it is unable to provide prophylaxis against PONV in the immediate postoperative period. Hence, delayed antiemetic efficacy might be the result of its pharmacokinetics, which may partially explain the lack of antiemetic effect during the 24 h observation period adopted for this study.

A number of studies have reported that combination therapy using 5HT3 receptor antagonists, such as ondansetron, tropisetron, or ramosetron with dexamethasone were more effective in reducing PONV than monotherapy.[32,33] Palonosetron being a newer 5HT3 receptor antagonist, with better efficacy than ondansetron; its combination with dexamethasone was also used. However, Blitz et al. claimed that palonosetron with dexamethasone did not reduce the incidence of PONV compared to palonosetron alone.[12] His study included elective outpatient laparoscopic abdominal or gynecological surgery with subjects having at least 3 Apfel'srisk factors for PONV, who were followed up for 72 h postoperatively (postoperative 0–2 h, 19 vs. 16%, 0–6 h 44 vs. 42%, 6–72 h; and 42 vs. 28%, palonosetron vs palonosetron + dexamethasone, respectively).[34] Bala et al. studied patients with high risk of PONV with added volatile and N2O. Their study was contrary to Blitz where N2O and volatiles were not used.[15] Bala concluded that Nausea occurred in 42.9% and vomiting in 33.3% in palonosetron group, whereas Nausea 14.3% and vomiting in 11.9% in P and D group during first 24 h postoperatively. Rajeeva et al. said that although the combination of dexamethasone and the older 5HT3 antagonist is more effective than 5HT3 antagonist alone, same is not true for the combination of dexamethasone and palonosetron.[35]

There has been no study evaluating palonosetron (0.075 mg) and dexamethasone (4 mg) combination to palonosetron or dexamethasone alone for intrathecal opioid-induced PONV. In our study P and D (0.075 mg palonosetron and 4 mg dexamethasone) combination was found to be equally effective as palonosetron (0.075 mg) alone but better than dexamethasone (8 mg) alone for PONV in cesarean section patient receiving intrathecal morphine. All patients had high-risk factors as all were female, nonsmoker status, receiving intraoperatively morphine. Rescue antiemetic requirement was more in Group D during early hours than the other two groups. There was no statistically significant difference between Group P and Group PD regarding rescue antiemetic consumption showing that combining dexamethasone and palonosetron does not give any additional benefit to patients.

Szarvas et al. conclude that ondansetron and dexamethasone combination was no better than ondansetron alone in patients undergoing a major orthopedic operation with spinal morphine as an adjuvant. The difference in studies between Rajeeva and Szilvia might be due to different patient groups in both studies. In Szilvias study, intrathecal morphine was used, whereas Rajeeva's patients were given GA. Hence, different patient groups, undergoing different surgeries with different anesthetic techniques need unique anti-emetic combination therapies for better PONV prophylaxis. The study tried to establish the efficacy of the combination of the newer 5HT3 antagonist, i.e., palonosetron with dexamethasone in pregnant patients receiving intrathecal morphine for LSCS.

Pruritus is an unpleasant and irritating sensation leading to scratching of the skin. It is the very common adverse effect of neuraxial opioids with the highest prevalence, i.e., up to 100% associated with intrathecal morphine administration which being water soluble. Parturients are more susceptible to pruritus with an incidence between 60% and 100%, and it appears to be estrogen related and dose-dependent.[36]

In the present study, low dose morphine (<200 μg) was used which resulted in a lesser incidence of pruritus complaints, but since there was no control group in our study, this could not be absolutely concluded.

Bonnet et al. reviewed the effect of prophylactic 5HT3 receptor antagonist on pruritus induced by neuraxial opioids concluding that they are helpful in decreasing the severity as well as incidence of pruritus.[37] Later, George et al. also concluded that 5HT3 receptor antagonist when used as prophylaxis decreased the severity of pruritus in women undergoing C-section with intrathecal morphine.[38] Jadon et al. did their study on such of patients with dexamethasone prophylaxis. They, however, concluded that dexamethasone alone did not reduce the incidence of pruritus.

The study results were much similar to above studies as there was a significant difference between the group receiving dexamethasone alone and the other two groups, regarding incidence of pruritus as indicated in Table 4. This clearly indicates that only dexamethasone as prophylaxis does not control intrathecal morphine-induced pruritus. However, palonosetron whether alone or in combination with dexamethasone was able to control pruritus.

CONCLUSION

Palonosetron and palonosetron–dexamethasone combination is superior to dexamethasone group alone in preventing intrathecal morphine-induced postoperative vomiting and pruritus. A combination of palonosetron and dexamethasone does not decrease the incidence of PONV and pruritus more compared to the only palonosetron. Hence, we recommend not to add dexamethasone to palonosetron as it will further increase the cost, risk of added side effects without any extra benefit.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gozal Y, Shapira SC, Gozal D, Magora F. Bupivacaine wound infiltration in thyroid surgery reduces postoperative pain and opioid demand. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1994;38:813–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1994.tb04010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahl JB, Jeppesen IS, Jørgensen H, Wetterslev J, Møiniche S. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of intrathecal opioids in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1919–27. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199912000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeh HM, Chen LK, Lin CJ, Chan WH, Chen YP, Lin CS, et al. Prophylactic intravenous ondansetron reduces the incidence of intrathecal morphine-induced pruritus in patients undergoing cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:172–5. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200007000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan TJ, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, Kovac A, Kranke P, Meyer TA, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2014;118:85–113. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rojas C, Thomas AG, Alt J, Stathis M, Zhang J, Rubenstein EB, et al. Palonosetron triggers 5-HT(3) receptor internalization and causes prolonged inhibition of receptor function. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;626:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tzeng JI, Wang JJ, Ho ST, Tang CS, Liu YC, Lee SC, et al. Dexamethasone for prophylaxis of nausea and vomiting after epidural morphine for post-caesarean section analgesia: Comparison of droperidol and saline. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:865–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/85.6.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Habib AS, Gan TJ. Evidence-based management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: A review. Can J Anaesth. 2004;51:326–41. doi: 10.1007/BF03018236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang PK, Tsay PJ, Huang CC, Lai HY, Lin PC, Huang SJ, et al. Comparison of dexamethasone with ondansetron or haloperidol for prevention of patient-controlled analgesia-related postoperative nausea and vomiting: A randomized clinical trial. World J Surg. 2012;36:775–81. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1446-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song JW, Park EY, Lee JG, Park YS, Kang BC, Shim YH, et al. The effect of combining dexamethasone with ondansetron for nausea and vomiting associated with fentanyl-based intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:263–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang SY, Jun NH, Choi YS, Kim JC, Shim JK, Ha SH, et al. Efficacy of dexamethasone added to ramosetron for preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting in highly susceptible patients following spine surgery. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;62:260–5. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2012.62.3.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bano F, Zafar S, Aftab S, Haider S. Dexamethasone plus ondansetron for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A comparison with dexamethasone alone. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:265–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szarvas S, Chellapuri RS, Harmon DC, Owens J, Murphy D, Shorten GD, et al. A comparison of dexamethasone, ondansetron, and dexamethasone plus ondansetron as prophylactic antiemetic and antipruritic therapy in patients receiving intrathecal morphine for major orthopedic surgery. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:259–63. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000066310.49139.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blitz JD, Haile M, Kline R, Franco L, Didehvar S, Pachter HL, et al. Arandomized double blind study to evaluate efficacy of palonosetron with dexamethasone versus palonosetron alone for prevention of postoperative and postdischarge nausea and vomiting in subjects undergoing laparoscopic surgeries with high emetogenic risk. Am J Ther. 2012;19:324–9. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e318209dff1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park JW, Jun JW, Lim YH, Lee SS, Yoo BH, Kim KM, et al. The comparative study to evaluate the effect of palonosetron monotherapy versus palonosetron with dexamethasone combination therapy for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;63:334–9. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2012.63.4.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bala I, Bharti N, Murugesan S, Gupta R. Comparison of palonosetron with palonosetron-dexamethasone combination for prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:779–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandrakantan A, Glass PS. Multimodal therapies for postoperative nausea and vomiting, and pain. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(Suppl 1):i27–40. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqui MA, Scott LJ. Palonosetron. Drugs. 2004;64:1125–32. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464100-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang LP, Scott LJ. Palonosetron: In the prevention of nausea and vomiting. Drugs. 2009;69:2257–78. doi: 10.2165/11200980-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rojas C, Stathis M, Thomas AG, Massuda EB, Alt J, Zhang J, et al. Palonosetron exhibits unique molecular interactions with the 5-HT3 receptor. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:469–78. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318172fa74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rojas C, Li Y, Zhang J, Stathis M, Alt J, Thomas AG, et al. The antiemetic 5-HT3 receptor antagonist palonosetron inhibits substance P-mediated responses in vitro and in vivo . J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:362–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovac AL, Eberhart L, Kotarski J, Clerici G, Apfel C Palonosetron 04-07 Study Group. A randomized, double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of three different doses of palonosetron versus placebo in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting over a 72-hour period. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:439–44. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31817abcd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SH, Hong JY, Kim WO, Kil HK, Karm MH, Hwang JH, et al. Palonosetron has superior prophylactic antiemetic efficacy compared with ondansetron or ramosetron in high-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2013;64:517–23. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2013.64.6.517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aouad MT, Siddik SS, Rizk LB, Zaytoun GM, Baraka AS. The effect of dexamethasone on postoperative vomiting after tonsillectomy. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:636–40. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200103000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee Y, Lin PC, Lai HY, Huang SJ, Lin YS, Cheng CR, et al. Prevention of PONV with dexamethasone in female patients undergoing desflurane anesthesia for thyroidectomy. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 2001;39:151–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JJ, Ho SJ, Wong CS, Tzeng JI, Liu HS, Ger LP. Dexamethasone prophylaxis for nausea and vomitimg after epidural morphine for post caesarean analgesia. Can J Anaesth. 2001;48:185–90. doi: 10.1007/BF03019733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen TK, Jones CA, Habib AS. Dexamethasone for the prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting associated with neuraxial morphine administration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:813–22. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318247f628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nortcliffe SA, Shah J, Buggy DJ. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after spinal morphine for caesarean section: Comparison of cyclizine, dexamethasone and placebo. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:665–70. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tzeng JI, Hsing CH, Chu CC, Chen YH, Wang JJ. Low-dose dexamethasone reduces nausea and vomiting after epidural morphine: A comparison of metoclopramide with saline. J Clin Anesth. 2002;14:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(01)00345-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan PH, Liu K, Peng CH, Yang LC, Lin CR, Lu CY. The effect of dexamethasone on postoperative pain and emesis after intrathecal neostigmine. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:228–32. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200101000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavorath R, Hesketh PJ. Drug treatment of chemotherapy-induced delayed emesis. Drugs. 1996;52:639–48. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199652050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jadon A, Sinha N, Agrawal A, Jain P. Effect of intravenous dexamethasone on postoperative nausea and vomiting after intrathecal morphine during caesarean section. S O J Anesthesiol Pain Manage. 2016;3:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holt R, Rask P, Coulthard KP, Sinclair M, Roberts G, Van Der Walt J, et al. Tropisetron plus dexamethasone is more effective than tropisetron alone for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in children undergoing tonsillectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2000;10:181–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2000.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.López-Olaondo L, Carrascosa F, Pueyo FJ, Monedero P, Busto N, Sáez A. Combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone in the prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76:835–40. doi: 10.1093/bja/76.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Apfel CC, Korttila K, Abdalla M, Kerger H, Turan A, Vedder I, et al. Afactorial trial of six interventions for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2441–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajeeva V, Bhardwaj N, Batra YK, Dhaliwal LK. Comparison of ondansetron with ondansetron and dexamethasone in prevention of PONV in diagnostic laparoscopy. Can J Anaesth. 1999;46:40–4. doi: 10.1007/BF03012512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szarvas S, Harmon D, Murphy D. Neuraxial opioid-induced pruritus: A review. J Clin Anesth. 2003;15:234–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(02)00501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonnet MP, Marret E, Josserand J, Mercier FJ. Effect of prophylactic 5-HT3 receptor antagonists on pruritus induced by neuraxial opioids: A quantitative systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:311–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.George RB, Allen TK, Habib AS. Serotonin receptor antagonists for the prevention and treatment of pruritus, nausea, and vomiting in women undergoing cesarean delivery with intrathecal morphine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:174–82. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181a45a6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]