Abstract

Background:

Multimodal analgesia is currently recommended for effective postoperative analgesia.

Aim:

The aim of this study is to compare the efficacy of transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block with intermittent transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in postoperative patients after infraumbilical surgeries under spinal anesthesia with respect to postoperative analgesia, rescue analgesia, hemodynamic changes, block characteristics, nausea/vomiting score, sedation score, adverse effects, and patient satisfaction.

Settings and Design:

This was a prospective, observational study randomized controlled trial.

Methods:

A total of 60 American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status Classes I and II patients of 20–60 years scheduled for infraumbilical surgeries were randomized by a computer-generated list into two groups of 30 each, to receive either TAP Block (Group TAP: 15 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine on each side of abdomen) or TENS (Group TENS: TENS with frequency of 50 Hz and intensity of electrical stimulation 9–12 mA, continued for 30 min every 2 h till 24 h). The primary outcome was to compare the postoperative analgesia as assessed using visual analog scale score. Secondary objectives were to compare rescue analgesia, nausea/vomiting score, sedation score, the block characteristics, adverse effects, hemodynamic changes, and patient satisfaction.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Student's t-test, Chi-square test as applicable and Statistical Package for Social Sciences (version 23.0, 2017, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used.

Results:

Time to the first analgesic requirement was 12.87 ± 4.72 h in Group TAP and 9.93 ± 3.63 h in Group TENS (P < 0.008), the difference between two groups was significant.

Conclusion:

TAP block is better modality due to ease of application and prolonged analgesia.

Keywords: Infraumbilical surgeries, postoperative analgesia, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, transversus abdominis plane block

INTRODUCTION

Multimodal analgesia is popular in the postoperative period for pain relief. Various types of nerve blocks are given in infraumbilical surgeries such as inguinal nerve block, paravertebral nerve block, caudal block, subarachnoid block, and transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block. TAP block is a regional analgesic technique which blocks T6–L1 nerve branches and has an evolving role in postoperative analgesia for lower abdominal surgeries. It is a simple and safe technique whether guided by traditional anatomic landmarks or by ultrasound. It has been shown to be effective in cesarean section,[1] hysterectomy,[2] open prostatectomy,[3] laparoscopic cholecystectomy,[4] and appendicectomy for postoperative analgesia.[5] Another technique for postoperative analgesia is transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) in which a special device transmits low voltage electrical impulses through electrodes on the skin to painful areas of the body. The use of TENS as nonpharmacological therapeutic modality is increasing.[6] TENS is cheaper, noninvasive, and safe with no side-effects compared to pharmacological analgesic modalities and it does not need expertise like other therapy forms. In addition to pain reduction by the use of this nonnarcotic, noninvasive technique; postoperative complications such as atelectasis and ileus are also reduced because patient can cough and breathe deeply without significant pain, it also decreases patient's stay in hospital, helps to achieve an earlier mobility and activity level and a decrease in the use of narcotics for pain control. Review of literature has revealed limited data comparing the potential of TAP block as an effective analgesic technique with TENS. Hence, we decided to compare the analgesic and postoperative analgesic efficacy of TAP block technique using levobupivacaine with TENS in patients undergoing infraumbilical surgeries.

METHODS

After obtaining the Institutional ethics committee's approval, this prospective observational randomized study was conducted on 60 patients in the age group of 20–65 years, of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classes I and II scheduled for infraumbilical surgeries under spinal anesthesia. After proper preanesthetic checkup and informed consent. Patients were randomly assigned using computer-generated list into two groups of 30 each. Group TAP patients were to receive TAP block (15 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine on each side), and group TENS were to receive TENS with the frequency of 50 HZ and intensity of electrical stimulation of 9–12 mA for 30 min every 2 h. Randomization was based on a computer-generated list (by software Microsoft Excel XP™) and sealed in opaque, sequentially numbered envelopes containing information regarding the assigned technique (TAP or TENS). Exclusion criteria were a patient refusal, coagulation disorders, any signs of sepsis, history of allergy to local anesthetic agents, body weight 20% higher than ideal body weight, significant renal, hepatic, cardiopulmonary or neurological disorders, or any anticipated difficulty in regional anesthesia. All patients were clinically examined in the preoperative period, and both techniques with their potential benefits and side effects were explained to them. Visual analog scale (VAS) of 10 cm line was also explained (0, no pain and 10, worst pain imaginable) during the preoperative visit. Routine blood investigations, a 12 lead electrocardiography (ECG), and chest X-ray was done in all patients. Preoperative fasting of minimum 8 h was ensured in all patients. In the operation theater, patients were connected to a standard multichannel monitor (Philips IntelliVue MP50) and baseline noninvasive systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP), heart rate (HR), peripheral O2 saturation (SpO2), and respiratory rate (RR) were recorded. Patients were cannulated and preloaded. Patients were premedicated with injection glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg intravenous and injection midazolam 2 mg intravenous in the operating room only before the procedure in both groups. Spinal anesthesia (2.5–3 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine) was given as per protocol and surgery was done. After the spinal block had receded below T10 dermatome, the TAP was performed with the patient in the supine position using landmark technique with Tuohy needle. A volume of 15 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine was injected in TAP through petit's triangle. TENS was applied with the patient in the supine position in group TENS.

Technique

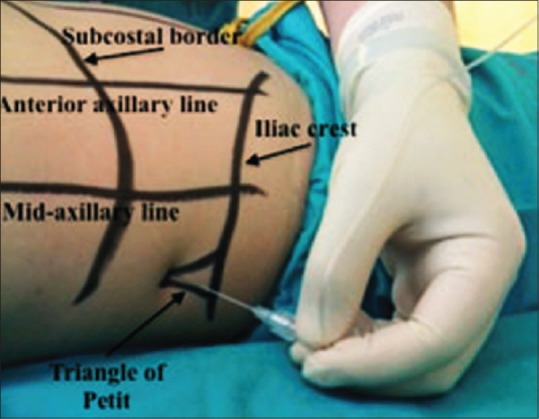

Group transversus abdominis plane

In this group, bilateral TAP block in the lumbar triangle of Petit was given at the end of surgery after sensory effect of spinal anesthesia receded below T10 dermatome. The iliac crest was palpated from anterior to posterior until the latissimus dorsi muscle could be felt. The triangle of Petit was then located only anterior to the latissimus dorsi muscle. The skin was pierced by Tuohy needle only cephalad to the iliac crest over the triangle of Petit [Figure 1], and the needle was advanced at a right angle to the skin in a coronal plane which resulted in a first pop sensation as the external oblique muscle gets traversed. Further advancement resulted in a second “pop” which signals entry to transversus abdominis fascial plane. After careful aspiration to exclude vascular puncture, 15 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine was injected in this plane on each side. The technique described by Rafi.[7]

Figure 1.

Landmark technique of transversus abdominis plane block

Group transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

After completion of the surgical procedure, TENS was started with portable TENS unit after block level had receded below T10 level. The TENS skin electrodes were positioned across the surgical incision site at adjacent dermatome levels. The frequency of TENS was set to 50 Hz and the intensity of electrical stimulation initially at 9–12 mA, which was reduced if not tolerated by the patient. It was continued for 30 min every 2 h until 24 h.

The primary outcome was to compare the postoperative analgesia as assessed by VAS score. The secondary outcome was to compare time to first rescue analgesia, nausea/vomiting score, sedation score, the block characteristics, adverse effects, hemodynamic changes, and patient satisfaction. On assessment when the VAS score was >3, rescue analgesia with injection tramadol hydrochloride, 50 mg i.v. was given. If pain persisted till next, i.v. 30 min, injection fentanyl 50 micrograms was administered. Continuous multiparameter monitoring of noninvasive SBP and DBP, HR, RR, SpO2, and ECG was done for a hemodynamic response. Readings were recorded preoperatively, then intraoperatively every 5 min up to 15 min, at interval of every 10 min until the end of surgery and then, every 25 min till spinal block regression to T10 level. 0 time was the time of giving the spinal anesthesia. Mean arterial pressure and HR were recorded after giving TAP and TENS and recorded at 0, 0.5, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h. Time when TAP block was given or TENS was applied was considered as 0 h. Patient satisfaction score was recorded postoperatively on a numeric rating scale from minimum 1 (very dissatisfied) to maximum 5 (very satisfied) at 24 h.

Sample size calculation

The “P” value was determined to finally evaluate the levels of significance. The P > 0.05 was considered nonsignificant; the value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and P < 0.001 was considered highly significant. Power analysis was performed to calculate the power of the study by taking α error 0.05. The effective size was calculated by taking parameters (postoperative analgesia, mean time to first analgesic requirement, and total duration of analgesia). The power achieved was well above 90%. Thus, a total of 60 patients were required at the least.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences); computer software version 23, 2017 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were analyzed using independent t-test. For comparing proportion between two groups, Chi-square test was applied and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

OBSERVATION AND RESULTS

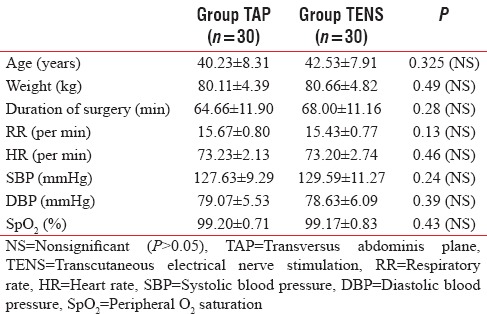

Sixty patients were recruited for this study, of which 30 patients were randomized to undergo TAP block with 15 ml of 0.25% levobupivacaine and 30 patients to received TENS with the frequency of 50 HZ and intensity of 9–12 mA for 30 min every 2 h. The two groups were comparable with respect to demographic data, i.e., age, weight, height, ASA class, baseline hemodynamic parameters, and duration of surgery [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic profile and baseline hemodynamic parameters of transversus abdominis plane block and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation groups

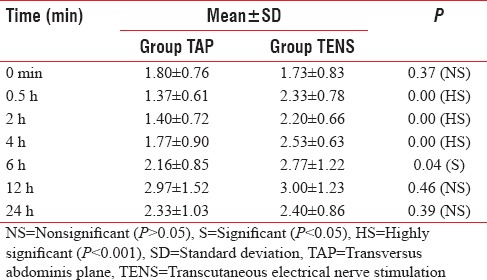

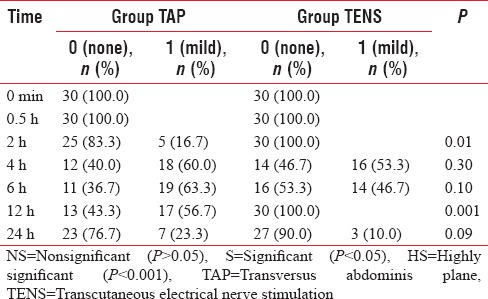

VAS score was evaluated with 0 h taken as the time of injection of 0.25% levobupivacaine in TAP in group TAP and application of portable TENS unit in group TENS, respectively. VAS score was recorded at 0, 0.5,2,4,6,12, and 24 h. Postoperative mean VAS scores at different time intervals were significantly lower in group TAP as compared to group TENS [Table 2].

Table 2.

Visual analogue scale score in the 24 postoperative h in the two different groups

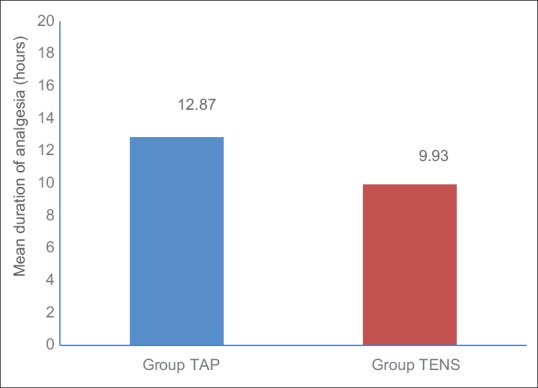

Time to first rescue analgesia

The mean duration of analgesia in Group TAP was significantly prolonged (12.87 ± 4.72) as compared to Group TENS (9.93 ± 3.63) (in hours), difference between two groups was significant (P = 0.008) [Figure 2]. Nausea was assessed at 0, 0.5, 2, 4, 6, 12, and 24 h using a categorical scoring system (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). Nausea was defined as a nausea score of >0 at any point of time postoperatively. Rescue antiemetic ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg was given when nausea score was 2 or more or vomiting occurred.

Figure 2.

Mean duration of analgesia after transversus abdominis plane and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (hours)

The incidence of nausea was found to be significantly lower in TENS group at 2 and 12 h. It was comparable at all other time intervals [Table 3].

Table 3.

Nausea/vomiting scores in the two different groups

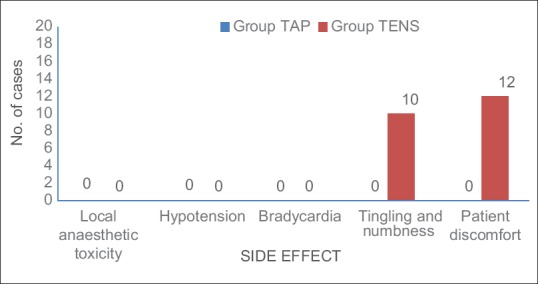

No complication was seen with TAP block. Ten patients in TENS group complained of discomfort and apprehension due to tingling sensation of TENS [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Side effects and complications

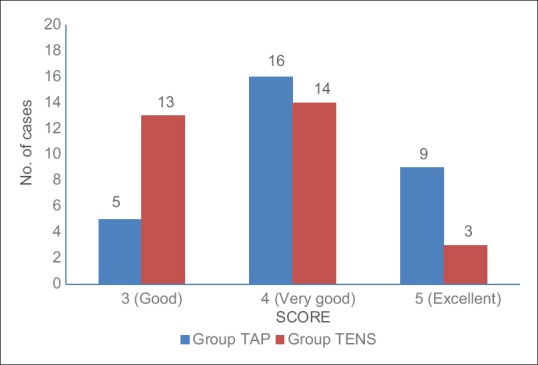

Mean patient satisfaction score was significantly higher in Group TAP as compared to Group TENS at 24 h [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Patient satisfaction score

DISCUSSION

Effective pain control is essential for the optimum care of patients in the postoperative period. Pain is an important factor leading to morbidity in surgical patients.[8] It requires continuous efforts to relieve postoperative pain during the postoperative period. It not only decreases the complications but also facilitates faster recovery.[9]

Multiple methods have been put into use to achieve pain-free recovery such as local anesthetic infiltration,[10] epidural analgesia,[11] peripheral nerve block,[12] and intravenous patient-controlled analgesia.[13] TAP block, which can be easily performed under ultrasound guidance[11] or using a landmark-based approach,[14] is becoming popular in lower abdominal surgeries to decrease postoperative pain. TAP block and TENS are currently described as an effective techniques for reducing postoperative pain and morphine consumption after lower abdominal surgery.[15,16]

TENS stimulates nerves endings by electrical stimulation and works on gate control theory of pain relief[17] which asserts that nonpainful input closes the “gates” to painful input, which prevents pain sensation from traveling to the central nervous system. Therefore, stimulation by the nonnoxious input can suppress pain. The analgesic effect of TENS has been found to be dependent on duration, intensity, the frequency of stimulation, and location of electrodes.[18]

Vas scores and duration of analgesia

Postoperative mean VAS scores at different time intervals were significantly lower in group TAP as compared to group TENS.

In this study, all time intervals, mean VAS score were observed to be <3 in both the groups. At 0 h, no patient required rescue analgesia in either group. Both the groups were comparable; and the difference was statistically nonsignificant (P = 0.37; nonsignificant). This was due to the residual effects of a local anesthetic drug administered in the spinal block before surgery. At 0.5 and 2 h, although no patient required rescue analgesia in either group still there was a significant difference in mean VAS between TAP and TENS groups, VAS in TAP being lesser than TENS group (P = 0.00; significant). This was due to faster onset of action of levobupivacaine which was administered in TAP group. At 4 h, one patient in TENS group had VAS >3, but no patient in TAP group had VAS >3. Thus, first rescue analgesic was given to one patient in group TENS. Although mean VAS was <3 in both the groups, but there was a significant difference in mean VAS with TAP, being lesser than TENS (P = 0.00; significant). At 6 h, two patients in group TAP and six patients in TENS group had pain (VAS >3), and hence, rescue analgesia (injection tramadol intravenous 50 mg) was administered to these patients. Difference in mean VAS in both the groups was significant at this point of time (P = 0.04; significant). Both the modalities were working well but TAP showed better results. Five patients required rescue at 8 h in group TENS whereas no such patient in group TAP required rescue at 8 h. At 12 h, 18 patients required rescue analgesia in group TAP and 12 patients in group TENS. This may be because many patients of TENS group had already been given rescue analgesia at 8 and 10 h. Hence, mean VAS was same in both the groups (VAS = 3) and was comparable (P = 0.46; nonsignificant). Prolonged analgesia due to the long duration of sensory block was the most significant characteristic of the TAP block technique. At 24 h, there was no significant difference in both the groups (with P = 0.39; nonsignificant) and mean VAS was <3 in both groups. The mean VAS score readings were lower in group TAP in comparison to group TENS and were statistically significant at 0.5, 2, 4, and 6 h. A meta-analysis was performed by Zhao et al.,[19] which found mean VAS score readings lower in group TAP and were statistically significant at 2 and 6 h. Similarly, a study by Kerai et al.[1] found that mean VAS score was lower in both the groups with significant difference between the VAS score at 0.5 and 4 h. The results were also in concordance with studies done by Sharma et al.[20]

In our study, mean duration of analgesia (time from 0 h to first rescue analgesia) in group TAP was 12.87 ± 4.72 h, whereas in group TENS, it was 9.93 ± 3.63 h. The difference between the two groups was highly significant (P = 0.008) and it was more prolonged in group TAP as compared to group TENS. This results from the relative avascularity of the plane and hence, the slow uptake of local anesthetics.

The study results were similar to a study done by Routray[21] on “TAP block using L-Bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in infraumbilical surgeries – A comparative study” which concluded that TAP block prolongs mean time for injection of first rescue analgesia in the study group as compared to placebo.

Nausea and vomiting score

The incidence of nausea was found to be significantly lower in TENS group at 2 and 12 h. It was comparable at all other time intervals. The results were in concordance with studies done by Kerai et al.[1]

Theories proposed to reduce nausea/vomiting through TENS are: stimuli via TENS facilitates productions of neurotransmitters that may inhibit other neurotransmitters that are responsible for nausea and vomiting.[22] No sedation was seen in patients of either group at any time interval and both the groups were comparable.

Patient satisfaction score

Patient satisfaction score was recorded postoperatively after 24 h. Score range varied from minimum 1 (very dissatisfied) to maximum 5 (very satisfied). The difference between the mean of patient satisfaction score in two groups was found to be significant (P < 0.05) at all intervals with patients being more satisfied with the TAP block.

At 24 h, the number of patients who were very satisfied (score 5) with the procedure was 30% in group TAP as compared to 10% in group TENS, while a number of satisfied (score 4) patients were 53.34% in group TAP and 46.67% in group TENS.

In this study, patients were more satisfied in group TAP than group TENS. This was because of better analgesia at all-time intervals and fewer complications like patient discomfort, tingling and numbness in group TAP.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study show that both TAP block and TENS are effective and safe modalities of analgesia following infraumbilical surgeries. Both decrease the requirement of opioids and their associated side effects. However, TAP block appears to be the better modality due to ease of application as there are residual effects of spinal anesthesia when the block is given and continuous monitoring is not required while TENS has to be applied at regular intervals. TAP block provides excellent postoperative analgesia as compared to TENS.

Limitations

One of the limitations of our study was small sample size, but it had significantly important results, so future studies should be undertaken with larger population size. Another limitation of the study was that landmark technique was used instead of ultrasound guided technique due to its nonavailability at our center. However, still, landmark technique has a place in a country like ours with limited resources where availability of ultrasound, especially in the rural setup is a long road to travel along with the need for expert hands for performing ultrasound-guided blocks.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerai S, Saxena KN, Anand R, Dali JS, Taneja B. Comparative evaluation of transversus abdominis plane block with transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for postoperative analgesia following lower segment caesarean section. J Obstet Anaesth Crit Care. 2011;1:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carney J, McDonnell JG, Ochana A, Bhinder R, Laffey JG. The transversus abdominis plane block provides effective postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:2056–60. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181871313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Donnell BD, McDonnell JG, McShane AJ. The transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in open retropubic prostatectomy. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006;31:91. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Dawlatly AA, Turkistani A, Kettner SC, Machata AM, Delvi MB, Thallaj A, et al. Ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane block: Description of a new technique and comparison with conventional systemic analgesia during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2009;102:763–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aveline C, Le Hetet H, Le Roux A, Vautier P, Cognet F, Vinet E, et al. Comparison between ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane and conventional ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks for day-case open inguinal hernia repair. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:380–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solak O, Emmiler M, Ela Y, Dündar U, Koçoiullari CU, Eren N, et al. Comparison of continuous and intermittent transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in postoperative pain management after coronary artery bypass grafting: A randomized, placebo-controlled prospective study. Heart Surg Forum. 2009;12:E266–71. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20081139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rafi AN. Abdominal field block: A new approach via the lumbar triangle. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:1024–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02279-40.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tuzuner Oncul AM, Yazicioglu D, Alanoglu Z, Demiralp S, Ozturk A, Ucok C, et al. Postoperative analgesia in impacted third molar surgery: The role of preoperative diclofenac sodium, paracetamol and lornoxicam. Med Princ Pract. 2011;20:470–6. doi: 10.1159/000327658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McHugh GA, Thoms GM. The management of pain following day-case surgery. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:270–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.2366_2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gupta A. Local anaesthesia for pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy – A systematic review. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005;19:275–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ventham NT, Hughes M, O’Neill S, Johns N, Brady RR, Wigmore SJ, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of continuous local anaesthetic wound infiltration versus epidural analgesia for postoperative pain following abdominal surgery. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1280–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler SJ, Christelis N. High volume local infiltration analgesia compared to peripheral nerve block for hip and knee arthroplasty-what is the evidence? Anaesth Intensive Care. 2013;41:458–62. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1304100404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gousheh SM, Nesioonpour S, Javaher Foroosh F, Akhondzadeh R, Sahafi SA, Alizadeh Z, et al. Intravenous paracetamol for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Anesth Pain Med. 2013;3:214–8. doi: 10.5812/aapm.9880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salman AE, Yetişir F, Yürekli B, Aksoy M, Yildirim M, Kiliç M, et al. The efficacy of the semi-blind approach of transversus abdominis plane block on postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair: A prospective randomized double-blind study. Local Reg Anesth. 2013;6:1–7. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S38359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johns N, O'Neill S, Ventham NT, Barron F, Brady RR, Daniel T, et al. Clinical effectiveness of transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block in abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e635–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdallah FW, Halpern SH, Margarido CB. Transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative analgesia after caesarean delivery performed under spinal anaesthesia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:679–87. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–9. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang SM, Kain ZN, White PF. Acupuncture analgesia: II. Clinical considerations. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:611–21. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318160644d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao X, Tong Y, Ren H, Ding XB, Wang X, Zong JY, et al. Transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:2966–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma P, Chand T, Saxena A, Bansal R, Mittal A, Shrivastava U, et al. Evaluation of postoperative analgesic efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block after abdominal surgery: A comparative study. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2013;4:177–80. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.107286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Routray SS. Transversus abdominis plane block using L-bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in infraumbilical surgeries – A comparative study. Sch J Appl Med Sci. 2016;4:3506–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oh H, Kim BH. Comparing effects of two different types of nei-guan acupuncture stimulation devices in reducing postoperative nausea and vomiting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2017;32:177–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2015.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]