Abstract

Background:

In this prospective, randomized study, we evaluated the intranasal administration of Midazolam ketamine combination, midazolam, and ketamine in premedication for children.

Material and Methods:

We studied 60 American Society of Anesthesiology physical status Classes I and II children aged between 1 and 10 years undergoing ear nose throat operations. All cases were premedicated 15 min before operation with intranasal administration of 0.2 mg/kg midazolam in Group M, 5 mg/kg Ketamine in Group K, and 0.1 mg/kg Midazolam + 3 mg/kg ketamine in Group MK. Patients were evaluated for sedation, anxiety scores, respiratory, and hemodynamic effects before premedication, 5 min interval between induction and postoperative period.

Results:

There was no difference with respect to age, sex, weight, the duration of the operation, and for mask tolerance. Sedation scores were significantly higher in Group MK. There was no statistically difference between the groups for heart rate, oxygen saturation, and respiratory rate.

Conclusion:

We concluded that intranasal MK combination provides sufficient sedation, comfortable anesthesia induction with postoperative recovery for pediatric premedication.

Keywords: Hemodynamic, nasal, pediatric premedication, sedation

INTRODUCTION

Thoughts of anesthesia and surgery exert emotional stress on both parents and children. Preoperative anxiety causes neuroendocrine responses in the pre- and post-operative period.[1,2] With a proper premedication anxiety can be prevented, psychological trauma can be reduced, induction of anesthesia can be easier. Premedication in pediatric group is a challenging situation. Children cannot totally understand the surgeries necessity. Before anesthesia, separation from parents leads to traumatic experiences in their young minds. In the past, so many different drugs with different routes have been used before surgery for psychological premedication.[3]

Premedication in children must act rapidly, must be acceptable and provide adequate analgesia with sedation. It should be atraumatic without hypersensitivity reaction and having rapid elimination. There has been no still ideal premedication.[4]

Intranasal premedication was first described by Wilton and García-Velasco et al. Intranasal premedication serves better conditions in children. Midazolam is an amnestic and sedative agent with minimal effects on ventilation and oxygen saturation (SpO2). Ketamine is sedative and anxiolytic, dissociative anesthetic agent. It does not have respiratory depression effects or delirium in children.[5,6]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After approval by Ethical Committee and obtaining parents' written consents we studied 60 American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA) physical status Classes I and II children aged from 1 to 10 years undergoing ear nose throat surgical procedures. Parents were informed about the premedication protocol. Moreover, apart from the initial explanation, no particular effort was made to encourage the parents' agreement. No parent insisted on exclusion. Children were randomly divided into three groups. Group M received intranasal 0.2 mg/kg midazolam, Group K received intranasal 5 mg/kg ketamine, whereas Group MK received 0.1 mg/kg midazolam-3 mg/kg ketamine. The calculated dose for each patient was administered in each nostril divided equally 15 min before general anesthesia drop by drop slowly over 5 min and children were asked to put their tongue out and instructed not to swallow. Induction of anesthesia was obtained with pentothal 5–7 mg/kg, rocuronium 0.5 mg/kg, and fentanyl 1 μg/kg after venous cannulation. In cases venous cannulation could not be performed, induction was obtained with inhalation anesthetics. Anesthesia was maintained with 50%O2–50%N02 and 2% Sevoflurane after tracheal intubation. The lungs were ventilated mechanically. All anesthetic drugs were discontinued at the end of the surgery and patients were extubated after the return of the reflexes and spontaneous ventilation. Paracetamol was administered as analgesic of choice.

Parents' refusal, ASA III and IV, congenital heart disease, previous history of convulsion, upper respiratory tract infection, children with central nervous system disorder, and children requiring emergency surgeries were excluded from the study.

Patients were evaluated for sedation scores, anxiety and respiratory scores, hemodynamic effects before premedication, at an interval of 5 min at the time of induction period to the postoperative period.

Patients were evaluated between the pre- and post-operative period:

Six-point sedation-anxiety scale

Peripheral SpO2

Mean arterial pressure

Pulse rate

Respiratory rate.

Heart rate and SpO2 were monitored throughout the procedure. Immediate reactions toward premedication were recorded. Adverse effects, if any, especially odd behavior or unexplained distress or excessive salivation were recorded.

Postprocedure, all the children were continuously monitored for nausea and vomiting, agitation, pulse rate, respiratory status in the recovery room until discharge to the ward. The children were discharged from the ward after they regained full consciousness, were able to sit or stand by themselves. Emergence reactions were noted.

Six-point sedation-anxiety scores

Restless

Cooperative-anxious

Drowsy

Drowsy-Response to commands

Drowsy-eyes closed-sluggish response to commands

No response to commands.

Separation reaction

Crying

Apprehension

Good.

Acceptance of mask

Refuses

Accepts with persuasion

Accepts readily.

Statistically analysis

Data were reported as arithmetic mean + standard deviation. Qualitative parameters degree of sedation on 6 points sedation scale, acceptance of mask, parental separation scores were analyzed using Chi-square and Fisher's exact test. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Significance tests were performed using unpaired t test and chi square test.

RESULTS

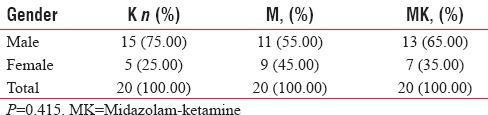

Ketamine group consisted of 15 boys and 5 girls. The average age in the K Group was 5.8 + 2.46 and in the M Group 5.5 + 2.59. The average weight in the K Group was 21.7 + 6.36 whereas in Group M with 11 boys and 9 girls 21.55 + 6.61. In the MK group, consisting of 13 boys and 7 girls, average age was 5.95 + 3.19 and the average weight 22.7 + 7.68 [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Demographic Data

Table 2.

Demographic Data

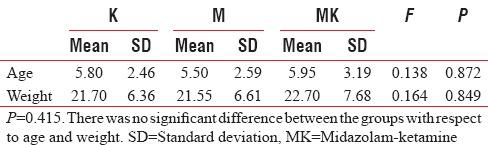

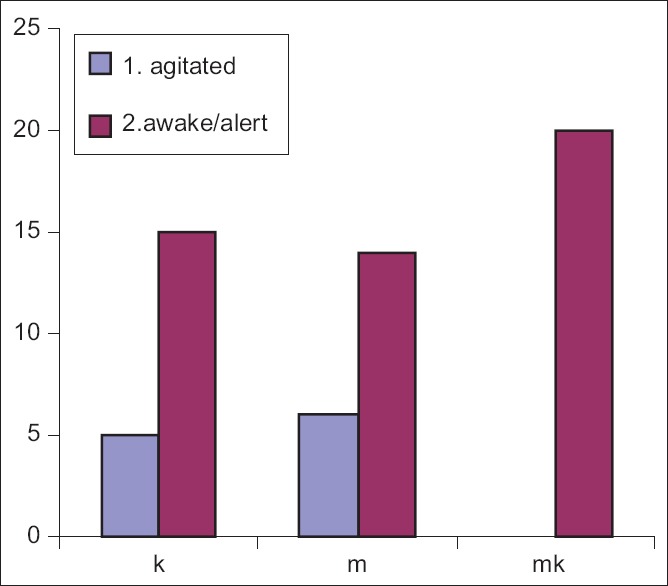

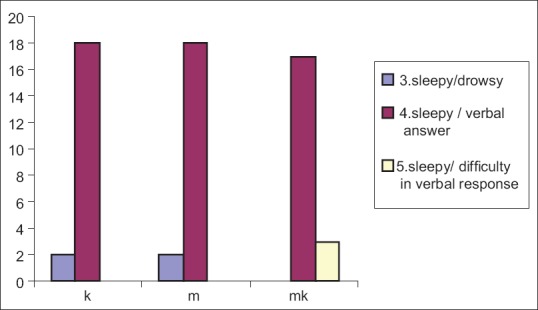

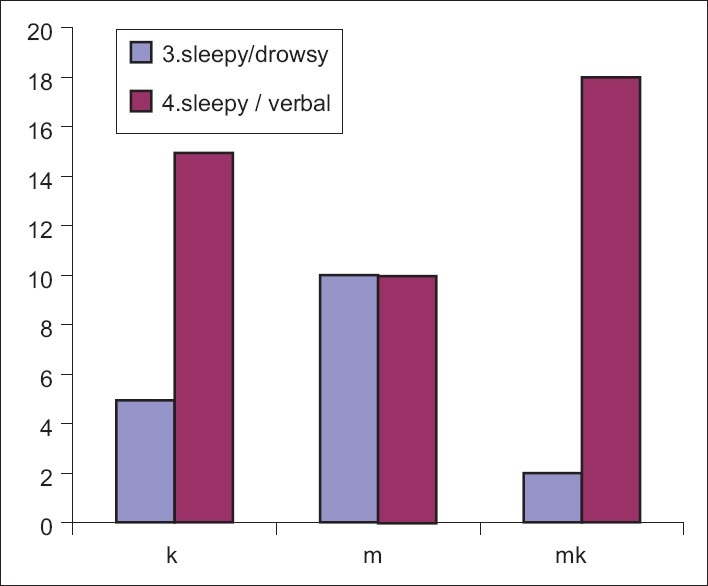

Nasally administered premedication was well tolerated. In Group M only two, in Group K one patient experienced burning sensation. All the children were anxious before premedication. Both groups were homogeneous population. Emerge reactions did not occur in any of the children. There was significant difference between the groups with respect to sedation scores at 5th min. Sedation score was high in MK group at 10th. min. There was no significant difference between the groups at the 15th minute [Figures 1–3].

Figure 1.

Sedation score at 5th min. There was significant difference between the groups with respect to sedation scores at 5th min. Sedation scores were higher significantly in MK Group. (P = 0.032), χ2 = 6.902 P = 0.032

Figure 3.

There was no significant difference between the groups at the 15th min (P = 0.090)

Figure 2.

Sedation score at 10th min. Sedation score was high in midazolam-ketamine Group at 10th min (P = 0.018)

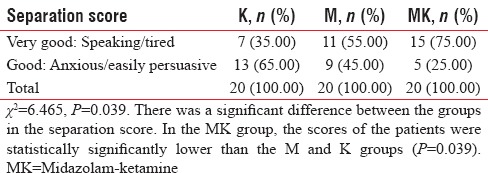

There was a significant difference between the groups in the separation score.

In the MK group, the scores of the patients were statistically significantly lower than the M and K groups [Table 3 and Figure 4].

Table 3.

Separation Score

Figure 4.

Separation score

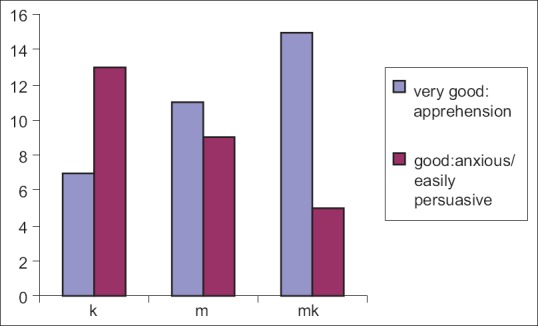

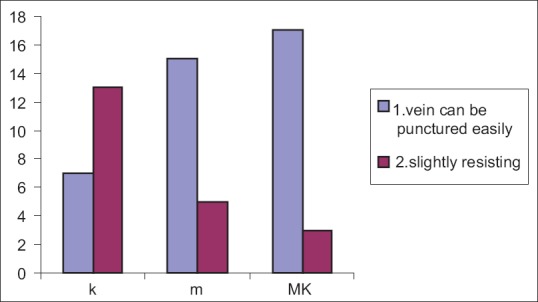

There was a significant difference between the groups in the venipuncture score.

The scores of the patients in the K group were statistically higher than those in the M and MK groups [Table 4 and Figure 5].

Table 4.

Venipuncture Score

Figure 5.

Venipuncture score

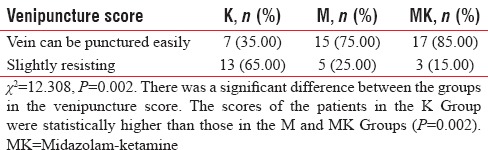

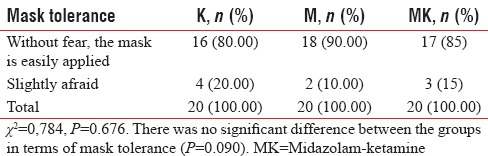

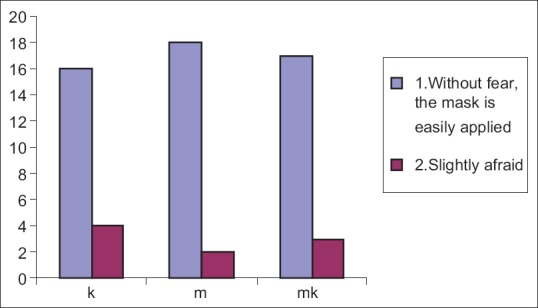

There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of mask tolerance [Table 5 and Figure 6].

Table 5.

Mask Tolerance

Figure 6.

Mask tolerance

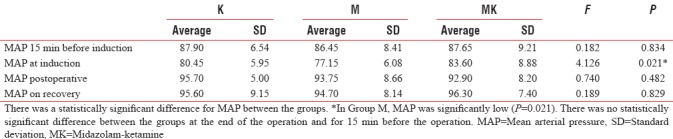

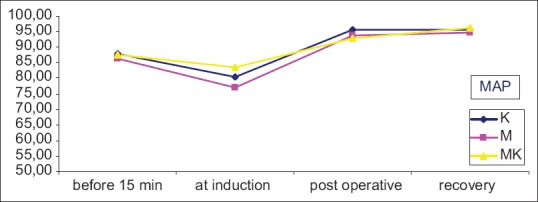

There was a statistically significant difference for MAP between the groups.

In group M; MAP was significantly low. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups at the end of operation and for 15 minutes before the operation [Table 6 and Figure 7].

Table 6.

Mean Arterial Pressure

Figure 7.

Mean arterial pressure

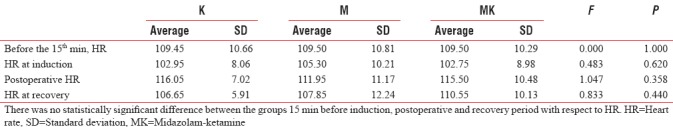

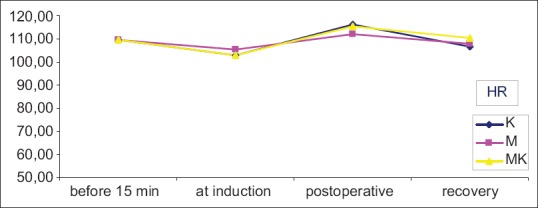

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups 15 minutes before induction, postoperative and recovery period with respect to Heart rate [Table 7 and Figure 8].

Table 7.

Heart Rate at Different Intervals

Figure 8.

Heart Rate

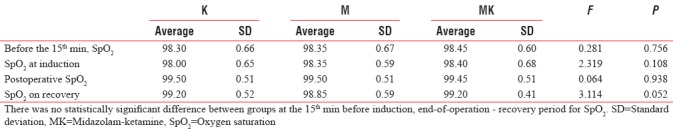

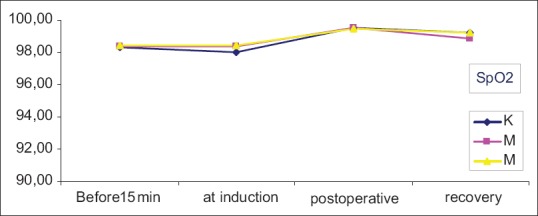

There was no statistically significant difference between groups at the 15th minute before induction, end-of-operation- recovery period for SPO2 [Table 8 and Figure 9].

Table 8.

Respiratory Rate

Figure 9.

* SpO2 evaluation was statistically significant at P < 0.05 level

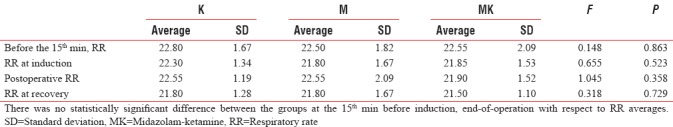

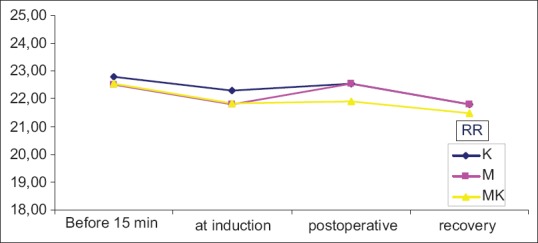

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups at the 15th minute before induction, end-of-operation with respect to RR averages [Table 9 and Figure 10].

Table 9.

Respiratory Rate

Figure 10.

*RR evaluation was statistically significant at the level of P < 0.05

DISCUSSION

The aim of the premedication in children is to facilitate the separation anxiety, eliminate the preoperative fears, to achieve smooth induction of anesthesia. In addition, premedication has analgesic, amnesic, antisialagogue, antiemetic, and vagolytic effects. Before surgery outcasting, the psychological preparation of the children many drugs have been used, but no ideal route of premedication has been found up to date.[7,8]

Ketamine and midazolam both have been used by various routes for pediatric premedication. Intranasal midazolam for premedication in preschool children was first described and introduced by Wilton et al. Racemic ketamine as a premedicant has been successfully administered through the nasal route.[5,9]

Intranasal application is absolutely noninvasive, convenient, and easy route of administration It results in a faster onset of action as well as reduces the first pass metabolism.[10]

Narendra studied 100 ASA I-II children aged between 1 and 10 years undergoing various surgical procedures. Totally, 50 children were received nasal ketamine at the dose of 5 mg/kg, and other 50 received nasal midazolam 0.2 mg/kg before induction. They found both midazolam and ketamine were effective pediatric premedication with midazolam's early onset of sedation and fewer side effects.[11]

Wilton et al., studied in 45 preschool children between 18 months and 5 years. They reported this route safe.[10]

Khatavkar and Bakhshi studied effects of intranasal midazolam and intranasal midazolam with ketamine for premedication of children aged 1–12 years undergoing intermediate and major surgeries. As found in our study quality of sedation, analgesia, and comfort is significantly better in midazolam with ketamine group. No side effects were seen in the groups.[11]

In Diaz's study 40 paediatric outpatients were assigned randomly in two separate study groups of equal size. The placebo group received 2 ml of saline intranasally 1 ml per naris. Study group received intranasal ketamine, 3 mg/kg-1, diluted to 2 ml with saline, 1 ml per naris. Intranasal ketamine achieved rapid separation of children from their parents, better acceptance of mask inhalation induction, and did not cause prolonged postanesthetic recovery. In our study, 11 children in Group Mi, 7 children in Group K were calm while separating from their parents. In Group MK, 15 children were calm and statistically significant.[12]

Weksler et al. administered ketamine in a dose of 6 mg.kg-1 nasally in 86 children (ASA I and II), undergoing elective general, urological or plastic surgery aged from two to five years and compared them with 62 others in whom promethazine and meperidine administered. They concluded nasal ketamine was an alternative to intra muscular preanaesthetic sedation.[13]

García-Velasco compared the efficacy and side effects of midazolam 0.25 mg/kg and ketamine 5 mg/kg nasally for the pediatric premedication. They stated that both drugs provided significant sedation in 10 min. In our study, we observed sedation in 10 min. In Group Mi significant sedation was observed in the 15th min.[6]

Malinovsky et al. compared different routes of premedication and concluded that intranasal way was the rapid sedation route. The other premedication routes can be painful, slow onset of sedation. Oral premedicants can be rejected also by children.[14]

In another study, Rose et al. stated the onset of sedation in 6 min with 0.2 mg/kg midazolam nasally. In our study, we observed the onset of sedation in 10 min, and in Group Mi, we reached significant sedation in 15 min. We concluded nasal route had the advantage of rapid absorption. In nasal routes drugs directly pass into the systemic circulation without passing through portal circulation.[15]

The absence of emergence delirium and other complications in this study highlight the safety of nasal ketamine with midazolam when used as a premedicants in pediatric patients. Excessive salivation which is one of the complications of parenteral administration of ketamine did not occur in our study.

Hence, continuous monitoring is necessary when midazolam and ketamine are administered. Minor respiratory depression can be seen with nasal midazolam and changes can be seen in pulse rate and SpO2.

In this study, we demonstrated the use of oral ketamine with midazolam for premedication provided better sedation, anxiolysis, good behavior at separation from the parents and satisfactory acceptance of face mask.

CONCLUSION

Unpremedicated children usually object to inhalational induction, and they feel the use of needles is one of the most worrisome aspects of the hospital stay. Both nasally midazolam added ketamine provide better and effective pediatric premedication. These drugs together reached adequate sedation, anxiolysis, easy separation from parents and acceptance of facemask, with no side effects at our studied doses. Further studies are necessary to determine the superiority of one route over the other.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kogan A, Katz J, Efrat R, Eidelman LA. Premedication with midazolam in young children: A comparison of four routes of administration. Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12:685–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber F, Wulf H, el Saeidi G. Premedication with nasal s-ketamine and midazolam provides good conditions for induction of anesthesia in preschool children. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:470–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03021058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edward G, Morgan MD, Maged S, Michael J, Murray MD. Clinic Anesthesiology. 4th. McGraw-Hill Company; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revcs JG, Glass PS. Miller RD, editor. Nonbarbiturate intravenous anesthetics. Anesthesia. 2005:243–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilton NC, Leigh J, Rosen DR, Pandit UA. Preanesthetic sedation of preschool children using intranasal midazolam. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:972–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García-Velasco P, Román J, Beltrán de Heredia B, Metje T, Villalonga A, Vilaplana J, et al. Nasal ketamine compared with nasal midazolam in premedication in pediatrics. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 1998;45:122–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filatov SM, Baer GA, Rorarius MG, Oikkonen M. Efficacy and safety of premedication with oral ketamine for day-case adenoidectomy compared with rectal diazepam/diclofenac and EMLA. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:118–24. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moscona RA, Ramon I, Ben-David B, Isserles S. A comparison of sedation techniques for outpatient rhinoplasty: Midazolam versus midazolam plus ketamine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1066–74. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199510000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dallimore D, Herd DW, Short T, Anderson BJ. Dosing ketamine for pediatric procedural sedation in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:529–33. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e318180fdb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain AA. Mechanism of nasal absorption of drugs. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;292:261–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khatavkar SS, Bakhshi RG. Comparison of nasal midazolam with ketamine versus nasal midazolam as a premedication in children. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:17–21. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.125904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diaz JH. Intranasal ketamine preinduction of paediatric outpatients. Paediatr Anaesth. 1997;7:273–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.1997.d01-93.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weksler N, Ovadia L, Muati G, Stav A. Nasal ketamine for paediatric premedication. Can J Anaesth. 1993;40:119–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03011307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malinovsky JM, Populaire C, Cozian A, Lepage JY, Lejus C, Pinaud M, et al. Premedication with midazolam in children. Effect of intranasal, rectal and oral routes on plasma midazolam concentrations. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:351–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb04616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose E, Simon D, Haberer JP. Premedication with intranasal midazolam in pediatric anesthesia. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1990;9:326–30. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(05)80243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]