Abstract

Background:

Intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetics in laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has been used to reduce postoperative pain and to decrease the need for postoperative analgesics.

Aims:

This study aimed to compare intraperitoneal instillation of bupivacaine and ropivacaine for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing LC.

Settings and Design:

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blind study.

Materials and Methods:

After obtaining ethical committee's clearance and informed consent, sixty patients, aged 18–65 years, of either gender, and American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status I to III scheduled for LC were included and categorized into two groups (n = 30). Group A patients received 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine intraperitoneally after cholecystectomy and Group B patients received 20 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine intraperitoneally after cholecystectomy.

Statistical Analysis:

The data were analyzed using paired t-test. The results were analyzed and compared to previous studies. SPSS software version 22 was used, released 2013 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results:

Pulse rate, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure were comparatively lower in Group B than in Group A. The visual analog scale (VAS) score was significantly lower in Group B. Rescue analgesia was given when VAS was >6. Verbal rating scale score was significantly lower in Group B, showing longer duration of analgesia in this group. Rescue analgesic requirement was also less in Group B.

Conclusion:

The instillation of bupivacaine and ropivacaine intraperitoneally was an effective method of postoperative pain relief in LC. It provided good analgesia in immediate postoperative period with ropivacaine, providing longer duration of analgesia.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, intraperitoneal, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, postoperative analgesia, ropivacaine

INTRODUCTION

The word pain has been derived from “Poena” which means penalty or punishment. Surgical pain is due to inflammation from tissue trauma (i.e. surgical incision, dissection, burns) or direct nerve injury (i.e. nerve transection, stretching, or compression). The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.”[1] Cholecystectomy is the most common operation of the biliary tract and the second most common operative procedure performed today.[2] Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has now replaced open cholecystectomy as the first choice of treatment for gallstones and inflammation of the gallbladder unless there are contraindications to the laparoscopic approach. This is because open surgery leaves the patient more prone to infection.[3] Although it is the belief of patients that laparoscopy has ushered a pain-free era, the fact remains that patients complain more of visceral pain after LC in contrast to parietal pain experienced in open cholecystectomy.[4]

Visceral pain has its maximal intensity during the 1st h and is exacerbated by coughing, respiratory movements, and mobilization. It is a distinctly separate form of pain compared to somatic pain.[5] Visceral signaling occurs through the enteric nervous system, which is complex and partly independent of the central nervous system, with a vast network of distinct and functionally diverse, neuronal subtypes.[6] Viscera such as the gallbladder and covering peritoneum convey unpleasant sensations and autonomic reactions to injury through afferents in the vagus nerve. These so-called “silent nociceptors” are activated by intraperitoneal inflammation and injury,[5] giving rise to both painful and nonpainful sensations that influence feeding and illness behaviors.[7]

Various multimodal approaches have, therefore, been tried to ameliorate postoperative pain. These include parenteral analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),[8] local infiltration with local anesthetics,[9] epidural and intrathecal opioids and local anesthetics, interpleural and intercostal nerve blocks as well as intraperitoneal routes that in turn have been explored with local anesthetics and opioids. It is also possible, however, to instill local anesthetic solutions into the peritoneal cavity, thereby blocking visceral afferent signaling and potentially modifying visceral nociception and downstream illness responses.

The present study aimed at comparing bupivacaine and ropivacaine as agents for pain relief by intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetics in patients after LC.

The aim of the study was to determine:

Duration of postoperative analgesic effect of 0.5% bupivacaine and 0.5% ropivacaine following intraperitoneal instillation in LC

Hemodynamic changes following intraperitoneal instillation of the above-mentioned drugs and need of rescue analgesia

Any side effects or complications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A prospective, randomized, double-blind study was conducted on sixty patients of American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I, II, and III of age group 18–65 years of either sex, admitted in the surgery department of our institute, and scheduled to undergo LC under general anesthesia after obtaining approval from Institutional Ethical Committee and informed consent from patients.

Allocation of groups

All patients were randomly divided into two groups of thirty each using sealed envelopes. A sealed envelope was randomly selected and opened by an assistant, with instruction to draw the relevant drug. The syringe was labeled with the patient's name and was given to the investigator to perform the block. An independent observer then observed the onset of sensory and motor blockades and analgesia till 24 h after blockades.

Group A: Patients who were given 20 mL of 0.5% bupivacaine intraperitoneally after gall bladder removal

Group B: Patients who were given 20 mL of 0.5% ropivacaine intraperitoneally after gall bladder removal.

Drug solution was prepared in prelabeled 20 mL syringes and injected intraperitoneally before the removal of main port at the end of surgery in Trendelenburg's position to facilitate the dispersion of the drug solution in the subhepatic region. In Group A, 0.5% of 20 mL bupivacaine was instilled, and in Group B, 0.5% of 20 mL ropivacaine was instilled by the surgeon as 10 mL (50%) of solution into the hepato-diaphragmatic surface, 5 mL (25%) in the area of gall bladder, and 5 mL (25%) into the space between the liver and kidney.

Postoperatively, the patients were assessed hemodynamically for heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and oxygen saturation (SpO2). Pain was assessed utilizing visual analog scale (VAS) and verbal rating scale (VRS). The patients were inquired about nausea, vomiting, frequency and dose of rescue analgesia using a predesigned pro forma, which was assessed at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h.

No supplemental analgesia was given till the patient complains of pain that is VAS score <6 in the postoperative period. Rescue analgesia was given in the form of NSAIDs, injection diclofenac sodium dose (75 mg intramuscularly). Injection ondansetron intravenous 4 mg was given for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Adverse effects if any were noted.

The data were systematically collected, compiled, and statistically analyzed to draw relevant conclusions. The above-mentioned parameters and patients' characteristics were compared using appropriate statistical tests. The data were analyzed using paired t-test. The P value was determined finally to evaluate the levels of significance. P > 0.05 was considered nonsignificant and P = 0.01–0.05 was considered significant. The results were analyzed and compared to previous studies. SPSS software version 22 was used, released 2013 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS

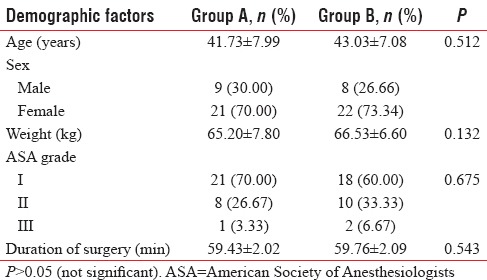

The following results were observed and statistically analyzed. In the present study, both the groups were comparable with respect to mean age, sex, duration of surgery, weight of the patients, and ASA distribution as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic profile

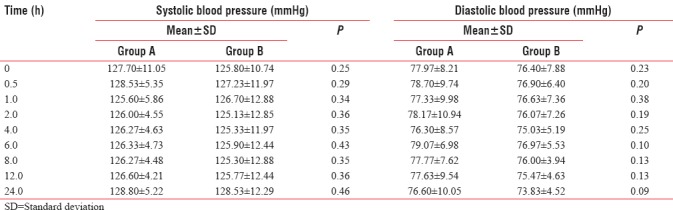

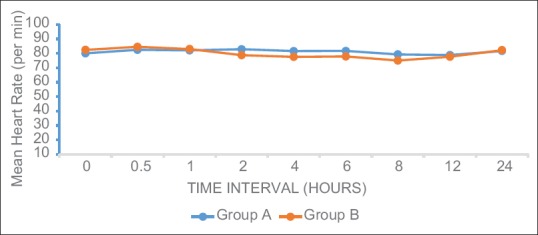

The mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings were recorded postoperatively in both the groups at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h. 0 time was the time of intraperitoneal instillation of the drug. The mean postoperative systolic blood pressure readings were found to be lower in Group B in comparison to Group A and the readings were stable and comparable in the two groups, with the difference being statistically insignificant (P > 0.05) as shown in Table 2. The mean postoperative heart rate per minute at 0 h in Group A and Group B was 80.03 ± 4.97 and 82.43 ± 9.35, respectively. The mean heart rate readings were lower in Group B in comparison to Group A. The results were comparable and the difference was found to be significant in the two groups at 2, 4, 6, and 8 h with P = 0.04, 0.03, 0.04, and 0.04, respectively, as shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Mean postoperative blood pressure (mmHg)

Figure 1.

Mean postoperative heart rate (per min)

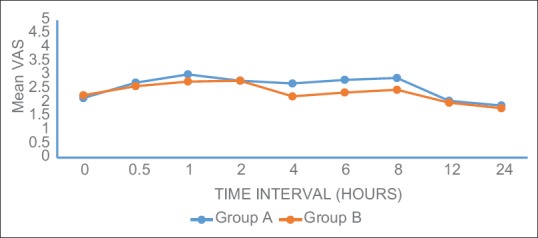

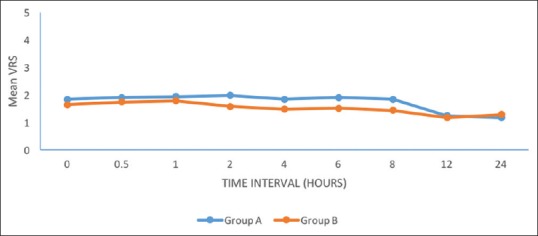

The mean VAS score readings were lower in Group B in comparison to Group A. The mean VAS score readings at 4, 6, and 8 h were statistically significant with P = 0.03, 0.02, and 0.04, respectively, as shown in Figure 2. The mean VRS score readings were lower in Group B in comparison to Group A. Mean VRS score readings at 2, 4, 6, and 8 h in both the groups were statistically significant with P = 0.02, 0.04, 0.03, and 0.02, respectively, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Mean visual analog scale score

Figure 3.

Mean verbal rating scale score

The number of patients requiring rescue analgesia was lower in Group B in comparison to Group A. All the readings were comparable and the difference was found to be nonsignificant in the two groups (P > 0.05). Time to first analgesic requirement was compared in both the groups. Time to first analgesic requirement in Group A was 150.00 ± 86.40 min and in Group B it was 162.22 ± 124.16 min. Complications were noted in <15% of the patients in both the groups. Nausea and vomiting were seen in four patients in Group A and three patients in Group B. Arrhythmias were noted in one patient in Group A and hypotension was seen in one patient in Group A. There was no arrhythmia and hypotension in Group B. There was no respiratory depression in any of the groups.

DISCUSSION

Local anesthetics have been administered into the peritoneal cavity during minimally invasive procedures, such as LC.[10] In comparison to open cholecystectomy, LC is associated with less pain. In the present study, the mean postoperative systolic and diastolic blood pressure readings were found to be lower in Group B and were stable and comparable in both the groups. The results were in concordance with a study done by Babu et al.,[10] where the vital parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and saturation were comparable between the groups. Similarly, Devalkar and Salgaonkar[11] found that in postoperative period, hemodynamic parameters such as heart rate and mean arterial pressure in both groups showed statistically significant difference (P < 0.01). No significant difference was found in respiratory rate and SpO2.

In our study, mean heart rate readings were lower in Group B in comparison to Group A. The results were comparable and the difference was found to be significant in the two groups at 2, 4, 6, and 8 h. In a study conducted by Devalkar and Salgaonkar,[11] heart rate was lower in the group which received 0.25% bupivacaine, with statistically significant difference at 0, 2, 4, and 8 h. In another study done by Meena et al.,[12] comparing bupivacaine and ropivacaine, heart rate readings were lower and statistically significant in ropivacaine group from the 1st to 9th h.

The mean VAS score readings were lower in Group B in comparison to Group A and were statistically significant at 4, 6, and 8 h. Devalkar and Salgaonkar[11] found mean VAS score readings to be lower in Bupivacaine group as compared to Normal saline group and were statistically significant at 2, 4, 8, and 12 h. Similarly, Meena et al.[12] in their study found that mean VAS score was lower in both the groups with significant difference between the VAS score from the 5th postoperative h to 12th h except in the 6th h. The results were also in concordance with studies done by Rapolu et al.[13] and Shivhare et al.[14]

In the present study, the mean VRS score readings were lower in Group B in comparison to Group A and were statistically significant at 2, 4, 6, and 8 h in both the groups. Similarly, Meena et al.[12] found that mean VRS score was lower in both the groups with significant difference between the VRS score in immediate postoperative period, 1st h, 3rd h, and then from 7th h to 12th h. The results were also supported by Khurana et al.[15]

In our study, the number of patients requiring rescue analgesia was lower in Group B in comparison to Group A. The readings were comparable and the difference, however, was found to be nonsignificant in the two groups. Kim et al. compared ropivacaine with normal saline and showed better analgesia with ropivacaine.[16]

Time to first analgesic requirement was compared in both the groups and was found to be lower in Group A. A study was conducted by Kucuk et al.[17] which showed that the intraperitoneal instillation of 100 mg bupivacaine, 100 mg ropivacaine, or 150 mg ropivacaine at the end of a LC significantly reduced the morphine consumption during the first 24 h. The results were also supported by Trikoupi et al.[18]

Complications were noted in <15% of the patients in both the groups. Nausea and vomiting were seen in four patients in Group A and three patients in Group B. Arrhythmias were noted in one patient in Group A and hypotension was observed in one patient in Group A. There was no arrhythmia and hypotension in Group B. There was no respiratory depression in any of the groups. All the readings were comparable and the difference was found to be nonsignificant in the two groups.

CONCLUSION

This study concludes that intraperitoneal instillation of local anesthetic solution in LC provides effective postoperative analgesia. Ropivacaine provided analgesia for longer duration as compared to bupivacaine and was associated with lesser side effects as compared to bupivacaine.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Merskey H, Fessard DG, Bonica JJ. Pain terms: A list with definition and terms of usage. Pain. 1979;6:249–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karam J, Roslyn JR. 12th ed. Vol. 2. New york: Prentice Hall International Inc; 1997. Cholelithiasis and cholecystectomy. Maingot's Abdominal Operations; pp. 1717–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soper NJ, Stockmann PT, Dunnegan DL, Ashley SW. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The new ‘gold standard’? Arch Surg. 1992;127:917–21. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420080051008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Møiniche S, Jørgensen H, Wetterslev J, Dahl JB. Local anesthetic infiltration for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopy: A qualitative and quantitative systematic review of intraperitoneal, port-site infiltration and mesosalpinx block. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:899–912. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200004000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervero F, Laird JM. Visceral pain. Lancet. 1999;353:2145–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns AJ, Pachnis V. Development of the enteric nervous system: Bringing together cells, signals and genes. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:100–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grundy D, Al-Chaer ED, Aziz Q, Collins SM, Ke M, Taché Y, et al. Fundamentals of neurogastroenterology: Basic science. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1391–411. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McColl L. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74:231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rees BI, Williams HR. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: The first 155 patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1992;74:233–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Babu R, Jain P, Sherif L. Intraperitoneal instillation: Ropivacaine vs. bupivacaine for post operative pain relief in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Health Sci Res. 2013;3:42–7. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devalkar PS, Salgaonkar SV. Intraperitoneal instillation of 0.25% bupivacaine for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Effect on postoperative pain. IJCMAAS. 2016;12:91–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meena RK, Meena K, Loha S, Prakash S. A comparative study of intraperitoneal ropivacaine and bupivacaine for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2016;20:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rapolu S, Kumar KA, Aasim SA. A comparative study on intraperitoneal bupivacaine alone or with dexmedetomidine for post-operative analgesia following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. IAIM. 2016;3:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shivhare P, Dugg P, Singh H, Mittal S, Kumar A, Munghate A. A prospective randomized trial to study the effect of intraperitoneal instillation of ropivacaine in postoperative pain reduction in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Minim Invasive Surg Sci. 2014;3:e18009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khurana S, Garg K, Grewal A, Kaul TK, Bose A. A comparative study on postoperative pain relief in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Intraperitoneal bupivacaine versus combination of bupivacaine and buprenorphine. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:23–8. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.164731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim TH, Kang H, Park JS, Chang IT, Park SG. Intraperitoneal ropivacaine instillation for postoperative pain relief after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Korean Surg Soc. 2010;79:130–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kucuk C, Kadiogullari N, Canoler O, Savli S. A placebo-controlled comparison of bupivacaine and ropivacaine instillation for preventing postoperative pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Today. 2007;37:396–400. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3408-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trikoupi A, Papavramidis T, Kyurdzhieva E, Kesisoglou I, Vasilakos D. Intraperitoneal administration of ropivacaine during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Anaesth. 2010;27:222. [Google Scholar]