Abstract

Context:

Postoperative sore throat (POST) is a very common complaint following tracheal intubation. Although it resolves spontaneously, efforts must be taken to reduce it.

Aims:

This study aims to compare the effect of cuff inflation using manometer versus conventional technique on the incidence of POST. Secondary objectives were to assess the incidence postoperative hoarseness and cough.

Settings and Design:

A total of 120 patients were included in this prospective observational comparative study.

Subjects and Methods:

After approval from the hospital ethics committee, consenting American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status Class I and II patients, scheduled for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia, were included. They were randomly allocated by closed envelope technique to either Group A where the cuff pressure was adjusted to 25 cmH2O using a manometer or Group B where cuff inflation was guided clinically. Patients were monitored for sore throat, hoarseness of voice, and cough postoperatively.

Statistical Analysis Used:

To calculate the incidence of sore throat, hoarseness, and cough, descriptive statistics were applied. For checking association of sore throat and cuff pressure, Chi-square test and for comparing numerical values independent sample t-test were applied.

Results:

The incidence of POST was significantly less in Group A than in B (P < 0.001) up to 24 h. Incidence of hoarseness was less in Group A and incidence of cough was higher in Group B, but these differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusion:

Cuff inflation guided by manometer significantly reduces the incidence of POST.

Keywords: Cough, cuff, hoarseness, intubation, laparoscopic, manometer, sore throat

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of postoperative sore throat (POST) varies from 30% to 70%.[1] It varies with size of endotracheal tube, anesthetic skill, duration of procedure, cuff design, high suction pressures, lack of humidification, and high airflow.[2] High cuff pressure is associated complications such as sore throat, tracheal rupture, laryngeal nerve palsy, and tracheoesophageal fistula.[3,4,5,6,7,8] Hence, it is recommended to maintain the cuff pressure between 20 and 30 cmH2O.[9] Conventionally, cuff inflation is guided by palpation of the pilot balloon and absence of audible leak during ventilation.[10] The aim of our study was to compare the incidence and severity of sore throat, with cuff inflation guided by manometer with conventional method.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This prospective, double-blinded, observational comparative study was conducted after obtaining hospital ethical committee approval and informed written consent from patients. The study was conducted from January 2014 to December 2016.

Sample size

Based on the incidence of sore throat in cuff inflated by manometer compared to control group (16.7% vs. 40%) from existing literature,[10] with 80% power and 95% confidence, minimum sample size was computed to be 60 in each group. One hundred and twenty American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status Class I–II patients, 18 years or older scheduled for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery under general anesthesia, were recruited and categorized into two equal groups by closed envelope technique. Patients with difficult airway, Mallampatti grading >II, who required >1 attempt at intubation, had preexisting cough or sore throat, or any other respiratory complaints and prolonged surgery were excluded from the study.

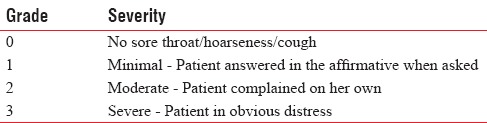

Standardized general anesthesia protocol was followed. All patients received oral ranitidine 150 mg, metoclopramide 10 mg, and alprazolam 0.25 mg on the night before surgery and ranitidine 150 mg and metoclopramide 10 mg on the morning of surgery. In the operation theater, intravenous (IV) cannula was inserted and monitoring with electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure monitor, and pulse-oximeter was done. Patients were preoxygenated with 100% O2; glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg, midazolam 2 mg, and fentanyl 2–3 μg/kg were given intravenously. They were then induced with IV propofol 1.5–2.5 mg/kg till there was a loss of response to verbal commands. Mask ventilation was performed with 100% O2 and isoflurane 0.5%–1.5%. Vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg IV was used after induction as skeletal muscle relaxant and a gentle quick laryngoscopy was done to intubate the patient with disposable 7.5-mm internal diameter cuffed (low pressure and high volume) polyvinyl chloride endotracheal tube. Endotracheal tube cuffs were filled with minimal volume of room air required to prevent an audible leak. If >2 attempts were required for intubation, the patients were excluded from the study. Both intubation and cuff inflation were performed by anesthetist posted in the theater. The cuff pressure was measured and it was set to 25 cmH2O using Portex cuff inflator (manufacturer: Smiths Medical International Ltd., UK) in Group A. In Group B, cuff inflation was guided by the absence of audible leak and by palpation of the pilot balloon as assessed by the anesthetist posted in the theater. An Ryles tube was then gently inserted through the nose. If >2 attempts were required for its insertion, the patient was excluded from the study. Anesthesia was maintained using O2 in air (1:2) and intermittent positive-pressure ventilation with isoflurane 0.5%–1.5%. Nitrous oxide use was avoided in all patients. IV vecuronium at 1/5th the induction dose was repeated at half and hour intervals or earlier if the patient showed signs of recovery from muscle relaxant. All patients were positioned in Trendelenburg position as required for gynecologic laparoscopic surgery. Toward the end of surgery, IV ondansetron 4 mg and IV paracetamol 1 g was given to all patients. On completion of surgery, residual muscle relaxation was reversed with IV neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 10 μg/kg and extubation was performed after gentle oropharyngeal suctioning under vision. Postoperative analgesia was provided with IV paracetamol 1 g 8th hourly. Postoperative cough, sore throat, and hoarseness monitoring and grading were done in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) by the nursing staff who were blinded to the technique and the responses were noted at 0, 2, 4, 12, and 24 h. The patients were asked to grade POST, cough, and hoarseness using a predefined category scale with scores 0–3 [Table 1].

Table 1.

Category scale score for assessment of sore throat/hoarseness/cough

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS 20.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To calculate the incidence of sore throat, hoarseness of voice, and cough in the postoperative patients, descriptive statistics were applied. For checking the association of sore throat and cuff pressure between the study and control groups, Chi-square test was applied. For comparing the numerical values between the study and control groups, independent sample t-test was applied. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

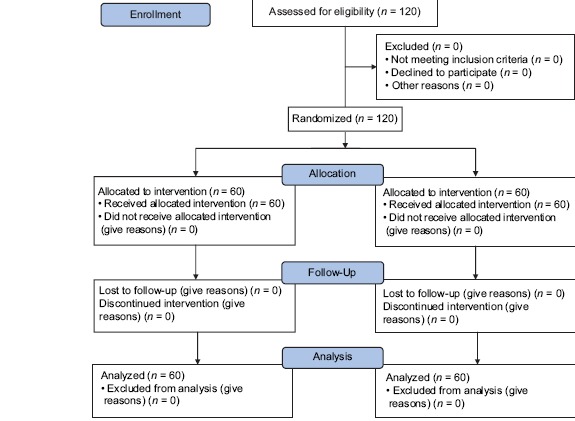

A total of 120 patients were recruited in this study [Flow diagram 1]. Distribution of patients in both groups was similar with respect to demographics, ASA distribution, Mallampatti scoring, and duration of surgery. The shortest duration of surgery was 120 min and the longest duration was 360 min. The incidence of sore throat was measured at 0, 2, 4, 12, and 24 h.

Flow Diagram 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

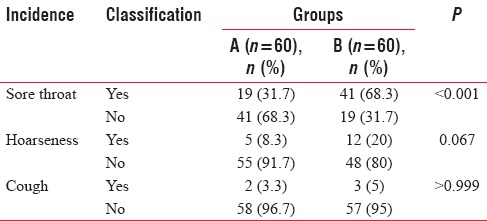

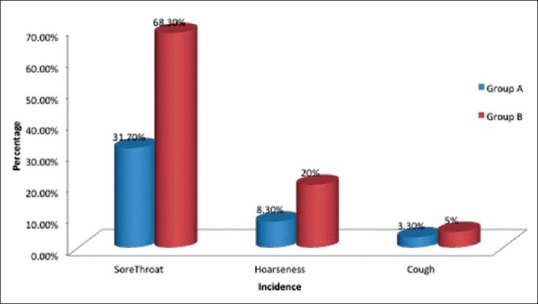

In Group A, 19 patients (31.7%) had sore throat as compared to 41 patients (68.3%) in Group B. This is statistically significant with P < 0.001. Five patients (8.3%) in Group A and 12 patients (20%) in the Group B had hoarseness of voice, which is not statistically significant with a P = 0.067. On comparing the incidence of cough between the groups, only two patients (3.3%) in the Group A had cough in the postoperative period whereas three patients (5%) in the Group B had cough. This was also not statistically significant [Table 2 and Figure 1].

Table 2.

Comparison of incidence of sore throat, hoarseness, and cough

Figure 1.

Incidence of sore throat, hoarseness, and cough

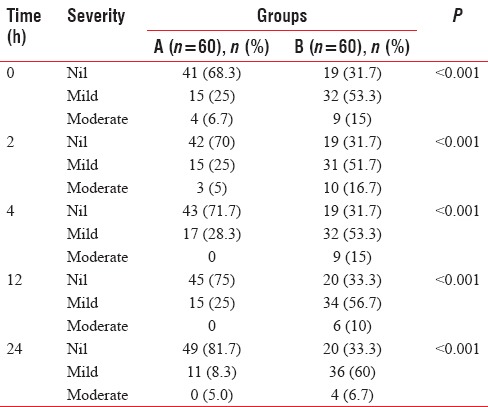

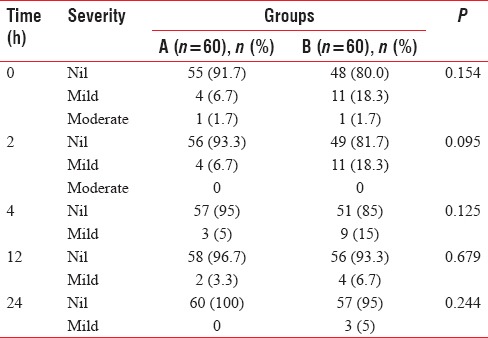

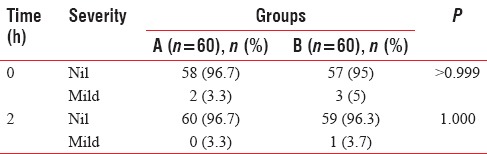

At all time periods, the incidence of sore throat was more in Group B as compared to the Group A and this was statistically significant [Table 3]. None of the patients in both the groups had severe sore throat. The incidence of hoarseness of voice was also compared at 0, 2, 4, 12, and 24 h in the postoperative period. The incidence of hoarseness was also clinically less in the Group A as compared to Group B. However, this was not found to be statistically significant at any time period [Table 4]. Three patients in Group B and two patients in Group A complained of cough. No statistically significant difference in the incidence of cough was found between the two groups with respect to cough in the postoperative period. As none of the patients had any complaints of cough after 2 h, statistical analysis was done only up to this time [Table 5].

Table 3.

Comparison of sore throat with groups in different time period

Table 4.

Comparison of hoarseness with groups in different time period

Table 5.

Comparison of cough with groups in different time period

DISCUSSION

Sore throat is a well-recognized minor complication after general anesthesia in the postoperative period.[2] Prophylactic management for decreasing its frequency and severity is recommended to improve the quality of postanesthesia care, though the symptoms resolve spontaneously without any treatment.[10] The purpose of inflating endotracheal cuff is to prevent leakage of gases during positive-pressure ventilation and aspiration of food or gastric fluid. However, overinflation of the cuff for prolonged periods can lead to mucosal injury. Excessive inflation for prolonged periods can affect the perfusion of tracheal mucosa resulting in ischemic necrosis, tracheal rupture, tracheoesophageal fistula, or laryngeal nerve palsy.[11] Hence, it is recommended to maintain the cuff pressure between 20 and 30 cmH2O.[12] The conventional method used to inflate the cuff is to fill the cuff till a seal is achieved by palpating for leak in the suprasternal notch during positive-pressure ventilation or by palpation of the pilot balloon.[10] However, blind inflation often leads to overinflation of the cuff resulting in increased postoperative respiratory morbidity.[12,13] In most hospitals, paramedics who are not trained to assess cuff inflation by conventional method would be inflating the cuff.[14] This lead to increased incidences of POST and other respiratory morbidities.

In our study, we compared the incidence of sore throat when cuff pressure (25 mmHg) was achieved with cuff manometer, with the conventional method of filling the cuff without measuring the cuff pressure. It was found that the incidence of sore throat was significantly higher in the latter group. Thus, it is important to use a cuff pressure manometer for better patient comfort and to avoid complications associated with cuff over inflation.

In a similar study by Nankar Archana et al.[10] on neurosurgery patients, it was found that cuff pressure monitoring by manometer reduced the incidence and severity of POST (16.7% vs. 40%). In our study, the incidence of POST in Group A with respect to Group B was also lower (31.7% vs. 68.3%). The relative higher incidences compared to this study could be attributed to the Trendelenburg position and pneumoperitoneum which itself increases the mucosal edema. The incidence of postoperative hoarseness was also less.

Ozer et al.[15] in their study on the influence of experience of the person on the cuff inflation pressure concluded that experience alone is not sufficient and a manometer should be used in routine inflation of the cuff to reduce the postoperative complaints. They also found a correlation between cuff pressure and anesthesia duration with postoperative complaints. Gilliland et al.[16] and Harm et al.[17] in their study found that cuff is likely to be overinflated if cuff pressure is not monitored with a manometer.

In a study conducted by Trivedi et al.,[18] routine cuff pressure measurements reduced endotracheal intubation-related complications. They recommended the use of simple manometer to guide cuff inflation than rely on subjective assessment. He found that anesthesiologist even with teaching experience of >5 years was not able to inflate the endotracheal cuff to the recommended range. Cuff is more likely to be overinflated when conventional methods are followed. Sultan et al.[19] in their review of the literature on endotracheal cuff pressure suggested that complications related to endotracheal intubation may be multifactorial, but elevated cuff pressure might be the major contributing factor and should be avoided. Studies have shown that cuff inflation by manometer is the best means of achieving ideal cuff inflation pressures.

Limitations of our study

Cuff pressure was measured only at the time of intubation and no measurements were taken during or at the end of surgery to determine if it remained the same until the end of surgery. Personnel with diverse experience performed intubation and their varying skill may have affected the results. Ryles tube insertion could have been a cause for increased sore throat. Head down position and pneumoperitoneum required for gynecological laparoscopic surgery could also have contributed to the increased sore throat. The degree of Trendelenburg position was not standardized in our study. This could have affected the results.

Future perspective

The study can be extended to a larger population with intermittent or continuous monitoring of cuff pressure during surgery; intubation by an experienced single anesthetist can be done to ensure there is no variation. Surgeries which do not require Ryles tube insertion could be selected for the study.

CONCLUSION

Cuff inflation guided by manometer significantly reduces the incidence of POST. Hence, cuff pressure manometer should be made available in all surgical theaters and ICU where endotracheal intubations are performed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tanaka Y, Nakayama T, Nishimori M, Tsujimura Y, Kawaguchi M, Sato Y, et al. Lidocaine for preventing postoperative sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD004081. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004081.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHardy FE, Chung F. Postoperative sore throat: Cause, prevention and treatment. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:444–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim H, Kim JH, Kim D, Lee J, Son JS, Kim DC, et al. Tracheal rupture after endotracheal intubation – A report of three cases. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;62:277–80. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2012.62.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang CY, Cheng SL, Chang SC. Conservative treatment of severe tracheal laceration after endotracheal intubation. Respir Care. 2011;56:861–2. doi: 10.4187/respcare.00891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yopp AC, Eckstein JG, Savel RH, Abrol S. Tracheal stenting of iatrogenic tracheal injury: A novel management approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1897–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jo YY, Park WY, Choi E, Koo BN, Kil HK. Delayed detection of subcutaneous emphysema following routine endotracheal intubation – A case report. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010;59:220–3. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2010.59.3.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miñambres E, Burón J, Ballesteros MA, Llorca J, Muñoz P, González-Castro A, et al. Tracheal rupture after endotracheal intubation: A literature systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:1056–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh S, Gurney S. Management of post-intubation tracheal membrane ruptures: A practical approach. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2013;17:99–103. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.114826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darkwa EO, Boni F, Lamptey E, Adu-Gyamfi Y, Owoo C, Djagbletey R, et al. Estimation of endotracheal tube cuff pressure in a large teaching hospital in Ghana. Open J Anesthesiol. 2015;5:233–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nankar Archana V, Aphale Shubhada S, Ladisushama D. Cuff pressure manometer: An essential tool to reduce the incidence of post operative sore throat. Innov J Med Health Sci. 2015;5:61–3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman RJ, Dahlen JR, Lipovic D, Stürmann KM. Linear correlation of endotracheal tube cuff pressure and volume. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10:137–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Metwalli RR, Sadek S. Safety and reliability of the sealing cuff pressure of the microcuff pediatric tracheal tube for prevention of post-extubation morbidity in children: A comparative study. Saudi J Anaesth. 2014;8:484–8. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.140856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stewart SL, Secrest JA, Norwood BR, Zachary R. A comparison of endotracheal tube cuff pressures using estimation techniques and direct intracuff measurement. AANA J. 2003;71:443–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braz JR, Navarro LH, Takata IH, Nascimento Júnior P. Endotracheal tube cuff pressure: Need for precise measurement. Sao Paulo Med J. 1999;117:243–7. doi: 10.1590/s1516-31801999000600004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozer AB, Demirel I, Gunduz G, Erhan OL. Effects of user experience and method in the inflation of endotracheal tube pilot balloon on cuff pressure. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16:253–7. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.110139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilliland L, Perrie H, Scribante J. Endotracheal tube cuff pressures in adult patients undergoing general anaesthesia in two Johannesburg academic hospitals. South Afr J Anaesth Analg. 2015;21:81–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harm F, Zuercher M, Bassi M, Ummenhofer W. Prospective observational study on tracheal tube cuff pressures in emergency patients – Is neglecting the problem the problem? Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2013;21:83. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-21-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Trivedi L, Jha P, Bajiya NR, Tripathi D. We should care more about intracuff pressure: The actual situation in government sector teaching hospital. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:314–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.68374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sultan P, Carvalho B, Rose BO, Cregg R. Endotracheal tube cuff pressure monitoring: A review of the evidence. J Perioper Pract. 2011;21:379–86. doi: 10.1177/175045891102101103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]