Key Points

FLCr ≥100 and BMPC ≥60% identify high-risk SMM, although with more modest median TTP and 2-year PD than previously published.

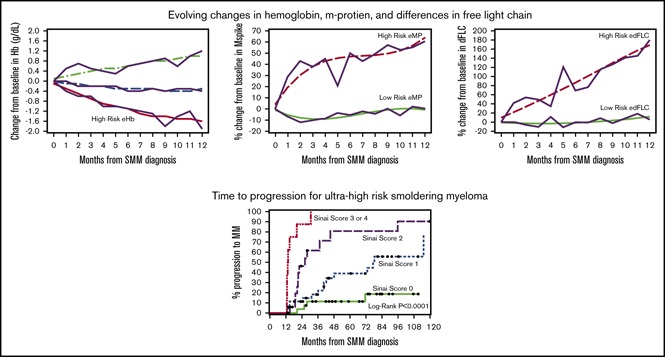

Baseline immunoparesis, eMP, eHb, and edFLC can help identify an ultra-high-risk SMM cohort.

Abstract

We investigated the predictive role for serum free light chain ratio (FLCr) ≥100, bone marrow plasma cell (BMPC) ≥60%, and evolving biomarkers through group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) as high-risk defining events in 273 smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) patients with a median follow-up of 74 months. FLCr ≥100 was confirmed as a marker for high-risk progression with a median time to progression (TTP) of 40 months with a 44% risk of progression of disease (PD) at 2 years; however, 44% of FLCr ≥100 also did not progress during follow-up. For patients with BMPC ≥60% by core biopsy, the median TTP was 31 months with a 2-year PD of 41%. GBTM established high-risk trajectories for evolving hemoglobin (eHb; characterized as a 1.57 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin), evolving m-protein (eMP; 64% increase in m-protein), and evolving differences in FLC (edFLC; 169% increase in dFLC) within 1 year of diagnosis associated with a decreased median TTP and an increased 2 year rate of PD. Of all the variables examined, we identify a model where immunoparesis, eHb, eMP, and edFLC were significant predictors for ultra-high-risk progression with a median TTP of only 13 months with 3 or more variables present. Our results not only confirm a more modest 2 year PD associated with FLCr ≥100 and BMPC ≥60 but also suggest that eHb, eMP, and edFLC may help identify an ultra-high-risk SMM group.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Smoldering multiple myeloma (SMM) is associated with 10% rate of progression to active MM annually for the first 5 years and 3% annually for the next 3 years compared with 1% annually for monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.1 In 2014, the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) updated its criteria for diagnosing MM from end-organ damage to include bone marrow plasma cell (BMPC) ≥60%, serum involved: uninvolved serum free light chain ratio (FLCr) ≥100, and magnetic resonance imaging/positron emission tomography-computed tomography/computed tomography (MRI/PET-CT/CT) with >1 focal lesion of 5 mm or greater. The goal of these updates was to identify a group of SMM patients at high risk of developing end-organ damage and to consider early therapy for these patients.2,3 The consensus was that biomarkers associated with 80% probability of progression to end-organ damage within 2 years or a median time to progression (TTP) of 12 months should be regarded as myeloma defining events and thus patients should be offered therapy.

Although 2 retrospective studies supported these updates, with median time to progression ranging from 13 to 15 months and 2-year progression rates as high as 98% for SMM patients with FLCr ≥100,4,5 another study found a rate of only 53%.6 Most important, the only prospective registry published found a rate of progression of only 30%.7 Also, although several studies have found BMPC ≥60% to be predictive of progression, each had very few such patients, with a cumulative sample size of only 45 patients across all published studies.5,8-10 Interestingly, 1 study compared BMPC determined by core biopsy (BMB) vs aspirate (BMA) and found that BMB ≥60% was not a predictor of rapid progression and only BMA ≥60% by aspirate was high risk.10

The importance of the kinetics of SMM evolution have been previously described for evolving changes in m-protein and hemoglobin within the first 12 months of SMM diagnoses with identification of an ultra-high-risk group of patients at >80% risk of progression at 2 years.11 More recently, another study also examined evolving changes in m-spike and found increases in 10% of m-protein by 12 months (if baseline m-protein ≥3 g/dL) or by 3 years (if baseline m-protein <3 g/dL) was associated with 71% risk of progression by 3 years independent of other standard risk factors of progression (m-protein ≥3 g/dL, BMPC ≥20%, or presence of immunoparesis).12 Early intervention in SMM patients requires not only evidence that early treatment can improve these patients’ long-term outcomes, but at minimum, reproducible criteria for the definition of high-risk SMM. The discrepancies in the predictive value of FLCr as well as the identification of evolving risk factors warrant further investigation. In this study, we survey characteristics and outcomes of SMM patients seen at our institution; we used a group-based trajectory modeling (GBTM) to compare evolving biomarkers, including the never previously investigated evolving FLC and evolving dFLC, as risk factors to identify a group of ultra-high-risk SMM.

Methods

Approval of this retrospective study was obtained from the institutional review board of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and the study was done in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Patients were identified by query of the electronic medical record for consecutive patients with the diagnosis of myeloma seen at Mount Sinai Hospital between 2010 and 2015. Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of SMM as defined by the 2003 IMWG definition: ≥10% BMPC or serum m-protein ≥3 and the absence of hypercalcemia (Ca ≥11.5 mg/dL), renal insufficiency (Cr ≥2 mg/dL or creatinine clearance <40 mL/minute), anemia (hemoglobin [Hb] ≤10 g/dL), and bone lesions (lytic lesions or diffuse osteopenia). Exclusion criteria were the absence of BMPC within 3 months of the time of SMM diagnosis and <1 year of follow-up. For analysis of evolving biomarkers, patients were required to have 2 or more laboratory tests within 12 months of SMM diagnosis in addition to their baseline value. Patients who participated in clinical trials involving agents known to have no single-agent activity were included in the analysis but also analyzed separately.

FLCs were measured using Freelite assay. FLCr was computed as a ratio of involved:uninvolved light chain. dFLC was computed as the difference between the involved and uninvolved light chain. BMPC is reported as the highest BMPC as determined by BMB or BMA unless otherwise stated. Immunoparesis is defined as reduction below the lower limit of normal in 2 uninvolved immunoglobulins (ie, IgG <700 mg/dL, IgA <70 mg/dL, Ig M <40 mg/dL). Progression to active disease was determined clinically by calcium elevation, renal dysfunction, anemia, and bone disease–related organ impairment, infection, or amyloidosis. Patients were censored if they were started on MM therapy in the absence of these events. Risk stratification for progression was performed according to the previously published Mayo baseline or evolving model.11,13

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). A “3-step approach” was adopted to estimate the relationship between latent class trajectories (described here) and TTP. All hypothesis testing was 2-sided with the type 1 error rate fixed at 5% for determination of factors associated with TTP.

GBTM was performed using an SAS macro named PROC TRAJ. This method identified distinct clusters of patients with similar patterns of evolving biomarkers within the first 12 months of SMM diagnosis: evolving Hb (eHb), evolving m-protein (eMP), evolving FLCr (eFLCr), and evolving differences in FLC (edFLC). Trajectory parameters were derived by latent class analysis using maximum likelihood estimation. In particular, the distinctive trajectories of biomarkers were derived by modeling the change (for Hb) and percent change (for m-protein and FLC), in each biomarker, from baseline, as a function of time since SMM diagnosis. Quadratic curves were used to model trends in Hb and FLC over time and cubic curves were used to model trends in m-protein over time. The optimal number of trajectories was determined using previously suggested guidelines14 and clinical relevance determined by research team. The output of PROC TRAJ included the equations for the different trajectories along with the assignment of each patient to 1 of the trajectory groups.

Once trajectory groups were estimated for each biomarker, the method of Kaplan-Meier was used to estimate median TTP for each group with high-risk patients defined as those with the shortest TTP. Time-dependent receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves for right censored survival data were estimated using the inverse probability of censoring weighting method previously described.15 Sensitivities, specificities, and accuracies from the 2-year ROC curves for progression of disease (PD) were calculated for high-/low-risk baseline (at SMM diagnosis) and evolving biomarker groups. Accuracy was defined as the proportion of true positives and true negatives in all evaluated patients. Areas under the 2-year ROC curves (AUCs) as well as integrated time-dependent AUCs (IAUC − average of all time-dependent AUC), were provided as metrics of model discrimination. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to identify prognostic risk factors for TTP. A complete case analysis was performed, with patients missing at least 1 variable excluded from the analysis. A covariate selection algorithm was used to identify the “best” subset of predictors in multivariable Cox modeling.16

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 273 patients with SMM met eligibility criteria; of these, 183 patients had FLCr within 3 months of diagnosis. Only 21 patients had to be censored at the time they began treatment of non-calcium elevation, renal dysfunction, anemia, and bone disease indications including infection (1), amyloid (2), rapid increase in paraprotein (4), BMPC ≥60 or FLCr ≥100 (7), other (4), and unknown (3). Of note, median (range) time to treatment from SMM diagnosis in these patients was 24.1 (6.3-74.6) months; median (range) time to treatment in the patients who were treated for BMPC and FLCr was 26.1 (7.4-72.3) months.

Patient characteristics are shown stratified by FLCr and BMPC (Table 1). The median age of the 273 patients at time of diagnosis was 60 years, with 52% males. The median BMPC at time of diagnosis was 20% with 92% of patients with BMPC <60%. The predominant isotype was IgG (72%) and IgA (21%) with κ (70%) and λ (29%) light chain distribution. The median m-protein was 1.9 g/dL (range, 0-5.3). Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was available for 149 patients, with 17% patients at high risk defined as t(4;14), del 17p, or +1q21.17,18 Initial imaging performed to rule out MM included bone surveys (52%), PET-CT (24%), and MRI (24%) scans. Bisphosphonate use was noted in 22% of patients for osteoporosis.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at SMM diagnosis stratified by FLCr ≥100 or <100 and BMPC ≥60 or <60

| Variables | All patients | FLCr <100 | FLCr >100 | P | BMPC <60 | BMPC >60 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 273 | 156 | 27 | — | 251 | 22 | — |

| Median age (range), y | 60 (20-90) | 60 (25-82) | 62 (33-75) | .93 | 60 (20-90) | 60 (36-77) | .82 |

| Male sex | 143/273 (52) | 80/156 (51) | 16/27 (59) | .77 | 130/251 (52) | 13/22 (59) | .51 |

| BMPC | |||||||

| Median (range), % | 20 (10-95) | 20 (10-80) | 30 (12-90) | .004 | 20 (10-50) | 70 (60-95) | <.0001 |

| Median %, if <60% | 20 | 20 | 22 | .02 | — | — | — |

| 10%-60% | 251/273 (92) | 147/156 (94) | 22/27 (81) | .02 | — | — | |

| Isotype | |||||||

| IgG | 196/273 (72) | 103/156 (66) | 21/27 (78) | .10 | 181/251 (72) | 15/22 (68) | .79 |

| IgA | 57/273 (21) | 41/156 (26) | 3/27 (11) | 51/251 (20) | 6/22 (27) | ||

| LC only | 13/273 (5) | 6/156 (4) | 3/27 (11) | 12/251 (5) | 1/22 (5) | ||

| Other (IgM, IgD, biclonal) | 7/273 (3) | 6/156 (4) | 0/27 (0) | 7/251 (3) | 0/22 (0) | ||

| Involved light chain | |||||||

| κ | 192/273 (70) | 108/156 (69) | 21/27 (78) | .64 | 178/251 (71) | 14/22 (64) | .68 |

| Λ | 79/273 (29) | 47/156 (30) | 6/27 (22) | 71/251 (28) | 8/22 (36) | ||

| Biclonal | 2/273 (1) | 1/156 (1) | 0/27 (0) | 2/251 (1) | 0/22 (0) | ||

| Serum monoclonal protein | |||||||

| Median m-protein (range), g/dL | 1.9 (0-5.3) | 1.7 (0.5-3) | 2.2 (0-4.2) | .23 | 1.8 (0-5.3) | 2.8 (0.4-43) | .003 |

| <3 g/dL | 189/220 (86) | 124/156 (79) | 20/24 (83) | .84 | 180/204 (8) | 9/16 (56) | .004 |

| ≥3 g/dL | 31/220 (14) | 22/156 (21) | 4/24 (17) | 24/204 (12) | 7/16 (44) | ||

| Free light chain | |||||||

| FLCr <100 | 156/183 (85) | — | — | — | 147/169 (87) | 9/14 (64) | .02 |

| FLCr >100 | 27/183 (15) | — | — | 22/169 (13) | 5/14 (36) | ||

| Median light chain concentration, mg/L | |||||||

| Median difference in involved and uninvolved FLC (range) | 61 (0-2838) | 45 (0-2418) | 532 (28-2838) | <.0001 | 57 (0-2838) | 129 (22-765) | .10 |

| Median κ of involved (range) | 59 (3-2862) | 46 (3-1288) | 633 (28-2862) | <.0001 | 56 (3-2862) | 107 (25-528) | .38 |

| Median Λ of involved (range) | 105 (2-2500) | 80 (2-2499) | 462 (117-1500) | .011 | 85 (2-2500) | 154 (36-769) | .23 |

| FISH risk | |||||||

| Available FISH, n | 149 | 96 | 18 | 138 | 11 | ||

| Normal | 61/149 (41) | 42/96 (43) | 4/18 (22) | .33 | 60/138 (43) | 1/11 (9) | .10 |

| Other risk | 30/149 (20) | 15/96 (16) | 4/18 (22) | 27/138 (20) | 3/11 (27) | ||

| Hyperdiploidy | 33/149 (22) | 20/96 (21) | 4/18 (22) | 28/138 (20) | 5/11 (46) | ||

| t(4;14), del17p, +1q21† | 25/149 (17) | 19/96 (20) | 6/18 (34) | 23/138 (17) | 2/11 (18) | ||

| t(4;14) | 14 (47) | 11 (5) | 3 (30) | 13 (50) | 1 (25) | ||

| del17p | 2 (6) | 1 (5) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 2 (50) | ||

| +1q21 | 14 (47) | 8 (40) | 6 (60) | 13 (50) | 1 (25) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Free light chain values at baseline were only available for 183 patients for free light chain ratio subgroup analysis.

The sum of all high-risk events is greater than the number of patients with high risk as patients may have met multiple high-risk criteria.

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics noted between all patients and the 183 patients with FLCr data available, with the exception of the year of diagnosis. When comparing patients diagnosed before and after 2001, the year of free light chain approval, as expected, more patients (100%) were missing FLC before this date vs 32% after this date.

FLCr was ≥100 in 27 (15%) patients. When compared with patients with FLCr <100, no significant differences were noted in median m-protein, isotype, or FISH risk. As expected, the FLCr ≥100 group had higher median differences between involved and uninvolved FLC (532 vs 45 mg/L, P < .0001), involved κ concentration (633 vs 46 mg/L, P < .0001), and involved λ concentration (462 vs 80 mg/L, P = .011) when compared with the FLCr <100 group. There was also a significant difference in risk stratification by the Mayo baseline risk model with only intermediate- and high-risk patients in FLCr ≥100 compared with the FLCr <100 group (P < .001). However, there were no differences in risk stratification by the Mayo evolving risk model between the FLCr subgroups (P = .42).

When comparing those with BMPC ≥60 to <60 the median m-protein was 2.8 vs 1.8, respectively (P = .003). More high-risk patients were noted with BMPC ≥60 when stratified by the Mayo baseline (P = .001) but not the evolving (P = .13) risk models.

Progression outcomes

With a median follow-up of 67 months, the median TTP for all patients was 74 months, predominantly from bone disease (52%) and anemia (50%) and to a lesser extent renal insufficiency (9%) and hypercalcemia (3%) (Table 2). No significant differences were noted in progression by bone disease vs other causes when comparing patients who had initial bone survey, PET-CT, or MRI scans to rule out active myeloma. However, of the patients who progressed by bone disease, the median TTP was 35 months (initial assessment by skeletal survey), 20 months (initial PET-CT scan), and 22 months (initial MRI scan), although it is important to note that the selection of imaging modality was based on the judgment of the treating physician.

Table 2.

Progression-free survival of SMM and symptoms at time of progression stratified by FLCr ≥100 or <100 and BMPC percentage ≥60 or <60

| All patients | FLCR <100 | FLCR ≥100 | P | BMPC <60 | BMPC ≥60 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 273 | 156 | 27 | 251 | 22 | ||

| Progressed, n (%) | 123 (45) | 56 (36) | 15 (56) | 107 (43) | 16 (73) | ||

| Progression event, n (%)* | |||||||

| Hypercalcemia | 4 (3) | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.0000 | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 1.0000 |

| Renal insufficiency | 11 (9) | 2 (4) | 3 (20) | .0599 | 11 (10) | 0 (0) | .3560 |

| Anemia | 62 (50) | 33 (59) | 10 (67) | .7677 | 52 (49) | 10 (63) | .2996 |

| Bone disease | 64 (52) | 25 (45) | 8 (53) | .5742 | 55 (51) | 9 (56) | .7173 |

Total number of progression events exceeds the number of patients who progressed as patients may have progressed by multiple events.

Progression was analyzed along FLCr and BMPC stratifications. Similar to the overall population, the symptoms of progression in the FLCr and BMPC groups were predominately anemia and bone disease (Table 2). There was a trend toward increased renal insufficiency in FLCr ≥100 (P = .06), although there were very few patients (n = 5) with adequate data for analysis. Patients with baseline Bence Jones proteinuria (BJP) were twice as likely to have FLCr ≥100 at baseline as patients without BJP (P = .01); however, there was no significantly increased risk of renal progression if baseline BJP was present (P = .57).

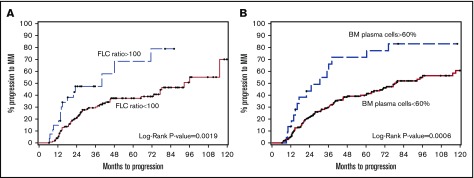

FLCr ≥100 had a specificity of 90% and sensitivity of 28% for predicting progression at 24 months (Table 3). BMPC ≥60 had a specificity of 94% and sensitivity of 15% for predicting progression at 24 months. Therefore, similar to previously published studies, FLCr ≥100 and BMPC ≥60 did predict for higher rates of MM progression than those without these features. However, the median TTP and 2-year PD rates were lower than reported initially: 40 months/44%, respectively, for FLCr ≥100 (Figure 1A) and 31 months/41%, respectively, for BMPC ≥60% (Figure 1B). Also, interestingly, 44% of the patients with FLCr ≥100 and 27% with BMPC ≥60% did not progress during the follow-up period. We also investigated baseline dFLC ≥100 mg/L as a subgroup because FLCr is very sensitive to small changes to the uninvolved free light chain when FLCr ≥100. dFLC ≥100 identified a high-risk cohort with a median TTP of 71-month and 2-year PD 36% (Table 3).

Table 3.

SMM outcomes risk stratified by baseline variables and evolving variables over 1 y

| n (%) | Median TTP, mo | Log-rank P | 2-y PD, % | Overall PD, % | Specificity, % | Sensitivity, % | Accuracy, % | 2-y AUC | Integrated time-dependent AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Factors | ||||||||||

| dFLC | ||||||||||

| dFLC <100 mg/L | 111 (41) | 92.6 | .0454 | 14 | 3 | |||||

| dFLC ≥100 mg/L | 72 (26) | 71.3 | 36 | 44 | 68 | 61 | 66 | 0.64 | 0.55 | |

| NE | 90 (33) | |||||||||

| FLCr | ||||||||||

| FLCr <8 | 81 (30) | 96.1 | .0325 | 12 | 31 | |||||

| FLCr ≥8 | 102 (37) | 71.3 | 31 | 45 | 51 | 76 | 56 | 0.63 | 0.55 | |

| NE | 90 (33) | |||||||||

| FLCr <100 | 156 (57) | 92.6 | .0019 | 19 | 36 | |||||

| FLCr ≥100 | 27 (10) | 40.2 | 44 | 56 | 90 | 28 | 75 | 0.59 | 0.59 | |

| NE | 90 (33) | |||||||||

| m-protein | ||||||||||

| <3 g/dL | 189 (69) | 115.2 | <.0001 | 20 | 38 | |||||

| ≥3 g/dL | 31 (11) | 21.8 | 45 | 74 | 91 | 29 | 75 | 0.60 | 0.47 | |

| NE | 53 (19) | |||||||||

| FISH* | ||||||||||

| Normal | 91 (33) | 73.0 | .1199 | 21 | 40 | |||||

| Hyperploidy | 33 (12) | 74.2 | 27 | 45 | ||||||

| High risk | 25 (9) | 36.1 | 32 | 52 | 85 | 21 | 58 | 0.53 | 0.58 | |

| NE | 124 (45) | |||||||||

| BMPC | ||||||||||

| <60 | 251 (92) | 79.2 | .0006 | 20 | 43 | |||||

| ≥60 | 22 (8) | 30.6 | 41 | 73 | 94 | 15 | 77 | 0.55 | 0.42 | |

| NE | 0 (0) | |||||||||

| Mayo evolving factors | ||||||||||

| eHB | ||||||||||

| No eHb | 94 (34) | 115.2 | .0002 | 12 | 30 | |||||

| eHb | 119 (44) | 42.2 | 29 | 51 | 51 | 77 | 55 | 0.64 | 0.61 | |

| NE | 60 (22) | |||||||||

| eMP | ||||||||||

| No eMP | 95 (35) | 96.1 | .0042 | 17 | 41 | |||||

| eMP | 106 (39) | 35.1 | 33 | 53 | 68 | 56 | 57 | 0.62 | 0.46 | |

| NE | 72 (26) | |||||||||

| GBTM factors | ||||||||||

| eHB | ||||||||||

| No eHb | 180 (66) | 115.2 | <.0001 | 14 | 35 | |||||

| eHb | 35 (13) | 26.3 | 43 | 66 | 89 | 36 | 79 | 0.62 | 0.43 | |

| NE | 58 (21) | |||||||||

| eMP | ||||||||||

| No eMP | 112 (41) | 115.2 | .0230 | 14 | 38 | |||||

| eMP | 33 (12) | 39.8 | 36 | 58 | 82 | 42 | 74 | 0.62 | 0.58 | |

| NE | 128 (47) | |||||||||

| eFLCr | ||||||||||

| No eFLCr | 108 (40) | NR | .0028 | 14 | 31 | |||||

| eFLCr | 19 (7) | 37.2 | 32 | 63 | 88 | 28 | 78 | 0.58 | 0.62 | |

| NE | 146 (53) | |||||||||

| edFLC | ||||||||||

| No edFLC | 104 (38) | 115.2 | .0586 | 13 | 33 | |||||

| edFLC | 23 (9) | 45.3 | 30 | 48 | 85 | 34 | 76 | 0.60 | 0.58 | |

| NE | 146 (53) |

Baseline factors are dFLC, FLCr, or BMPC at the time of SMM diagnosis. Mayo evolving factors are defined as evolving m-protein/Ig or evolving Hb over the first 12 mo of diagnosis as defined by Ravi et al. GBTM factors are determined using statistical software from evolving Hb, evolving m-protein, evolving FLCr, or evolving dFLC over the first 12 mo of diagnosis.

NE, not evaluable; NR, not reached.

For calculation of 2-y diagnostic statistics (specificity, sensitivity, accuracy, AUC), normal/hyperdiploidy/other FISH cytogenetic groups were combined.

Figure 1.

TTP to symptomatic myeloma stratified by free light chain ratio and BMPC percentage. (A) Median time to progression was 40 months in FLCr ≥100 compared with 93 months in FLCr <100 (P = .0019). (B) Median time to progression was 31 months in BMPC ≥60 compared with 79 months in BMPC <60 (P = .0006).

Given the previously inconsistent predictive value of BMPC, the predictive values of BMB (n = 254) and BMA (n = 146) were also analyzed. A cutoff of BMB ≥60 (n = 21) had a median TTP and 2-year PD of 25 months and 43%, respectively. A BMA ≥60 cutoff appeared to correlate more with PD, with a median TTP and 2-year PD of 22 months and 67%, respectively, although there were only 3 such patients. Both BMB and BMA ≥60 identified high-risk groups with shorter median TTP and higher 2-year PD than their respective counterparts.

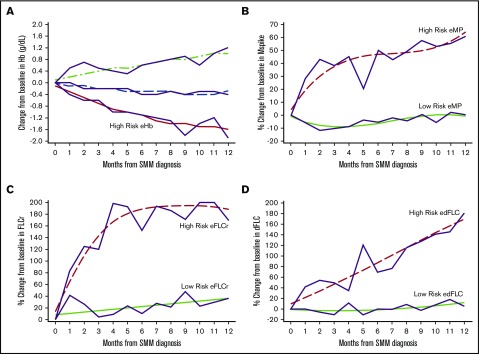

GBTM identified high-risk groups of patients based on 1 year post-SMM diagnosis trajectories of their Hb, m-protein, FLCr, and dFLC (Figure 2). The high-risk eHb group experienced on average a decrease of 1.57 g/dL (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.29-1.84) in Hb at 1 year. High-risk eMP patients experienced an average increase of 64% (95% CI, 44-84) in m-protein at 1 year. High-risk eFLCr patients experienced an average increase of 188% (95% CI, 183-193) in FLCr at 1 year. High-risk edFLC patients experienced on average an increase of 169% (95% CI, 143-195) in dFLC at 1 year. The GBTM-identified high-risk groups had significantly shorter median TTP and higher 2-year PD rates of 26 months/43% (eHb), 40 months/36% (eMP), 37 months/32% (eFLCr), and 45 months/30% (edFLC) relative to their low-risk counterparts (Table 3). Of note, eHb and eMP, as defined by the Mayo evolving model, individually had a median TTP/2-year PD of 42 months/29% and 35 months/33%, respectively, in our SMM population.

Figure 2.

Evolving changes in hemoglobin, m-protein, free light chain ratio, and differences in free light chain identified through GBTM 1 year after diagnosis of SMM. (A) Changes in Hb are in g/dL. Changes in m-protein (B), free light chain ratio (C), and differences in free light chain ratio (D) are % from baseline. The trajectories of high risk evolving GBTM groups are indicated.

Baseline and GBTM evolving characteristics were available for 90 patients and were analyzed for their contribution to predicting PD using previously identified high-risk factors.11,13 The median (range) of the number of repeated tests are as follows: Hb 3 (2-12), M-protein 4 (2-12) and FLC 3 (2-10). BMPC ≥20%, m-protein ≥3 g/dL, immunoparesis, eHb, eMP, eFLCr, and edFLC were identified as significant contributors in univariable analyses models (Table 4). However, when analyzed in a multivariable model, immunoparesis, eMP, eHb, and edFLC were identified as the 4 most significant predictors of 2-year PD.

Table 4.

Multivariable model predicting SMM risk for PD

| n = 90* | Univariable | Multivariable | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Age | 1.002 (0.97-1.03) | .9007 | ||

| Male | 0.88 (0.47-1.65) | .6824 | ||

| BMPC ≥20% | 3.29 (1.45-7.49) | .0046 | ||

| BMPC ≥60% | 0.98 (0.30-3.25) | .9790 | ||

| m-protein ≥3 g/dL | 3.59 (1.80-7.17) | .0003 | ||

| IgA SMM | 0.72 (0.30-1.73) | .4645 | ||

| Immunoparesis | 2.90 (1.46-5.77) | .0025 | 3.90 (1.80-8.44) | .0006 |

| FLCr ≥100 and dFLC ≥100 | 1.53 (0.59-3.99) | .3827 | ||

| dFLC ≥100 mg/L | 1.36 (0.70-2.64) | .3658 | ||

| eMP | 3.64 (1.89-6.99) | .0001 | 3.98 (1.80-8.44) | <.0001 |

| eHb | 4.54 (2.22-9.29) | <.0001 | 8.05 (3.53-18.35) | <.0001 |

| eFLCr | 2.09 (1.04-4.21) | .0395 | ||

| edFLC | 3.02 (1.45-6.27) | .0031 | 2.84 (1.28-6.29) | .0100 |

Only 6 patients had BMPC ≥60%, thereby limiting detection of statistical differences in progression curves at this cutoff.

HR, hazard ratio.

Patients were required to have all listed variables to be eligible for complete case analysis.

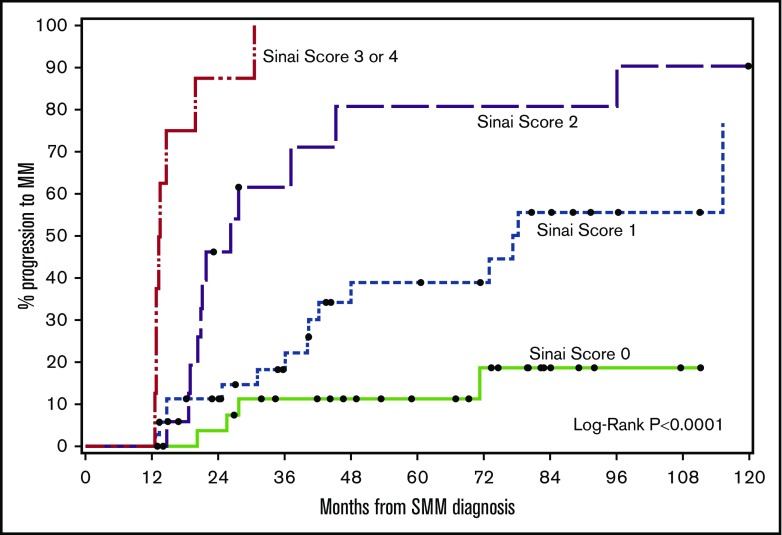

Ultra-high-risk patients by our multivariable model (≥3 risk factors) had a median TTP of 13 months and 2-year PD of 88% (Figure 3). The results of our 4-factor GBTM multivariable model were compared against previous risk stratification models applied to our patients (Table 5). The specificity of our model was 99% compared with 93% (Mayo baseline) and 85% (Mayo evolving).11,13

Figure 3.

TTP to symptomatic myeloma stratified based on risk factors (immunoparesis, eHb GBTM, eMP GBTM, and edFLC GBTM). The median times to progression for 0, 1, 2, or ≥3 risk factors were not reached: 77, 26, and 13 months, respectively (P <.0001).

Table 5.

Comparison of high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma

| n = 90* | n (%) | Median TTP, mo | Log-rank P | 2-y PD, % | Overall PD, % | Specificity, % | Sensitivity, % | Diagnostic accuracy | 2-y AUC | Integrated time-dependent AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mayo Clinic baseline score† | ||||||||||

| 1 | 37 (41) | 96.1 | .0218 | 8 | 32 | |||||

| 2 | 43 (48) | 48.1 | 26 | 44 | ||||||

| 3 | 10 (11) | 24.7 | 50 | 80 | 93 | 25 | 79 | 0.70 | 0.59 | |

| Mayo Clinic evolving score‡ | ||||||||||

| 0 | 10 (11) | 115.2 | <.0001 | 0 | 20 | |||||

| 1 | 34 (38) | 96.1 | 9 | 35 | ||||||

| 2 | 24 (27) | NR | 21 | 33 | ||||||

| 3 | 22 (24) | 21.8 | 50 | 77 | 85 | 58 | 79 | 0.78 | 0.68 | |

| Mount Sinai multivariable score§ | ||||||||||

| 0 | 29 (32) | NR | <.0001 | 3 | 14 | |||||

| 1 | 36 (40) | 77.3 | 11 | 42 | ||||||

| 2 | 17 (19) | 26.3 | 41 | 71 | 86 | 74 | ||||

| 3 or 4 | 8 (9) | 13.4 | 88 | 100 | 99 | 35 | 86 | 0.85 | 0.74 |

Patients were required to have all listed variables described for the complete case analysis.

BMPC ≥10%, m-protein ≥3 g/dL, FLCr ≥8.

BMPC ≥20%, eMP (≥10% increase in m-protein and/or immunoglobulin within the first 6 mo and/or ≥25% increase in m-protein and/or immunoglobulin within the first 12 mo), eHb (≥0.5 g/dL decrease within the first 12 mo).

Immunoparesis, eHb GBTM, eMP GBTM, edFLC GBTM.

Of the 35 SMM patients enrolled in clinical trials involving agents with no single-agent activity, there were 4 and 19 in the FLCr ≥100 and <100 groups, respectively, and 5 and 24 in the BMPC ≥60 and <60 groups, respectively. Compared with the nonclinical trial population, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics or distribution according to Mayo baseline or evolving risk models. Their removal slightly increased the median TTP but did not affect the GBTM modeling.

Discussion

Although there is great interest in treating high-risk SMM population to avoid end-organ damage, this must be counterbalanced by early and potentially indefinite therapy of some patients who may not necessarily progress. In this study, we examined the outcomes of 273 SMM patients followed at our institution.

Similar to other studies, progression events in our study predominantly resulting from anemia and bone lesions.4,5 Of the patients who progressed by bone disease, ∼50% in our study were detected either by PET-CT or MRI scans, illustrating the importance of sensitive bone imaging. The progression by renal failure was also comparable with 9% in our patients vs 11% to 18% in other studies.4,5 Among those with FLCr ≥100, the rate of renal PD was 20% vs 27%, as previously reported.4 Although those with baseline BJP were twice as likely to have FLCr ≥100 at baseline, there was no associated increased risk of renal PD. There were insufficient patients to analyze evolving BJP in our GBTM or multivariable model; this warrants further study.

Although FLCr ≥100 and BMPC ≥60 were confirmed as high-risk groups in our study, the groups’ prognosis was better than initial studies reported. The median TTP in FLCr ≥100 was 40 months, with 2-year progression at 44% and ultimate progression at 56%. When compared with previously published studies (Table 6), all previous studies have shown shorter median TTP for FLCr ≥100 with the exception of the Danish study, in which median TTP was not even reached. Furthermore, our 2-year progression rate falls between previously reported values that range from 30% to 98%. The 56% overall rate of progression is substantially lower in our study than previously reported in 2 other studies.

Table 6.

Comparison of high-risk SMM at various institutions

| Mayo Clinic4 | University of Athens5 | University of Pennsylvania6,8 | Denmark7 | MM GIMEMA-Latium Working Group10 | Mount Sinai | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of centers | Single | — | Single | Multi | Multi | Single |

| Inclusion criteria* | Yes | — | — | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| FLCR | ||||||

| Years of SMM diagnosis | 1970-2010 | — | 2008-2012† | 2005-2013 | — | 2003-2015 |

| n | 586 | 96 | 118 | 209 | — | 185 |

| Median TTP, mo | 40 | 66 | 82 | ‡ | — | 78 |

| FLCR ≥100, n (%) | 90 (15) | — | 11 (9) | 23 (11) | — | 27 (15) |

| Median TTP, mo | 15 | 13 | 20 | ‡ | — | 40 |

| 2-y progression, % | 72 | 98§ | 64 | 30 | — | 44 |

| Overall progression, % | 98 | 100 | — | — | — | 56 |

| BMPC | ||||||

| Years of SMM diagnosis | 1996-2010 | — | 2008-2012† | — | 1980-2010 | 1992-2015 |

| n | 655 | 96 | 121 | — | 397 | 273 |

| Median TTP, mo | 40 | 66 | 82 | — | — | 74 |

| BMPC ≥60, n (%) | 21 (3.2) | 8 (8) | 6 (5) | — | 10 (2.5)|| | 22 (8) |

| Median TTP, mo | 7 | 15 | 1.2 | — | — | 31 |

| 2-y progression, % | 95 | 95.5¶ | 100 | — | 100 | 41 |

| Overall progression, % | — | 100 | 100 | — | 100 | 73 |

Stipulation that laboratory data be obtained within 3 mo of diagnosis.

Years of investigation, not diagnosis, was provided in methodology.

Not enough patients progressed to calculate median TTP.

Data at 14 mo.

n = 7 by bone marrow biopsy core; n = 10 by bone marrow aspirate.

Data at 18 mo.

The marked heterogeneity in median TTP and progression rates for FLCr ≥100 may be due to several reasons. First of all, FLC measurements can vary depending on reagents, Freelite (the Binding Site Group Ltd.) a monoclonal-based antisera vs N Latex FLC assay (Siemens Healthcare) a polyclonal-based antisera, immunonephelometric vs immunoturbidimetric technique, and the choice of the analyzer used. In fact, most patients with FLCr of 100 by Freelite would be <100 by N Latex FLC.19,20 Single-institution studies may also suffer from either increased referral from local oncologists or self-referral of patients with perceived higher of risk of progression. Indeed, the Danish study, the only prospective registry published to date, has the lowest rate of PD. Another possibility is the period of investigation, with some studies dating back to the 1970s; improvements in diagnosis (in particular, greater use of whole-body low-dose CT, PET-CT, and/or MRI scans to rule out active myeloma) may have appropriately excluded active myeloma patients in recent studies. Finally, the requirement for an FLCr within 3 months from SMM diagnosis is not clearly stated in all studies and the absence of this inclusion criterion might skew results as well. It is worth noting that the lack of standardized baseline and following up testing time points for both serologies as well as appropriate radiologic studies is an important limitation of all SMM retrospective studies, including ours, and should give pause when prospective/registry studies are yielding discrepant results.

In patients with BMPC ≥60, the median TTP was 31 months with 41%/73% 2-year/overall PD rates, which are lower than previously reported median TTP ranging from 7 to 15 months, and nearly all patients progressed to active myeloma. BMB tend to have larger numbers of plasma cells than BMA and, in the United States, BMB are routine, whereas in Europe (eg, the GIMEMA study), all patients had a BMA but only ∼50% also had a BMB.21,22 Of the 127 patients who had both procedures, 7 had a BMB ≥60%, but the only early PD occurred in the patient with concordant BMA ≥60%. Given the limited number of patients studied to date (a combined global sample size of 45) and sampling issues (not only BMB vs BMA, but also heterogeneous MM involvement of the marrow), the optimal threshold for BMPC % in predicting a high-risk SMM cohort by BMB warrants further study.

FLCr and BMPC at the time of SMM diagnosis share the same limitation in predicting MM progression: baseline disease burden and characteristics do not take into account disease biology and evolution of the disease. It is now known that the majority of cytogenetic changes in MM can also be detected in monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and that the progression to MM likely involves the expansion of preexisting clones regulated by growth-permissive and restrictive signals from immune cells, bone cells, and other cells in the bone marrow niche.23 The lack of progression by more than one-third of our FLCr ≥100 patients led us to an investigation of evolving biomarkers to identify an ultra-high-risk group for progression. Through GBTM, we identified groups at high risk for progression based on the evolving trajectories of eHb, eMP, eFLCr, and edFLC rather than through arbitrary percent changes. Although no single biomarker, neither baseline nor evolving, predicted 80% 2-year PD, multivariable analysis identified a model in which immunoparesis, eHb, eMP, and edFLC were significant predictors for MM progression, with a median TTP and 2-year PD of 13 months and 88% when ≥3 were present. Of note, only edFLC (and not eFLCr) maintained significance in multivariable analysis, perhaps because of immunoparesis capturing the suppression of the uninvolved FLC that affects FLCr. Although requiring validation, these results suggest that, similar to the use of FLCr and dFLC in symptomatic MM and although baseline FLCr may be more significant in predicting SMM progression, evolving changes in dFLC may be more suitable for SMM monitoring.

The findings in this study support previous findings that FLCr ≥100 and BMPC ≥60 identify high-risk SMM patients, but with a more modest progression to MM than previously published. Further investigation into whether the predictive value of these biomarkers alone warrant treatment of otherwise asymptomatic patients is needed. This is particularly relevant for BMPC ≥60 given the few patients with this finding in all published studies combined. Furthermore, the GBTM identified high-risk variables need to be further validated in other large data sets. Taken together, these suggest that a meta-analysis with pooled multi-institutional data from previously published studies, as is being proposed by the IMWG, would be of great benefit. This would allow a global, standardized risk stratification, avoid the inadvertent initiation of treatment of patients who may remain asymptomatic for long periods, and ensure appropriately powered prospective therapeutic studies because of a better understanding of the expected rates of progression without intervention. Most important, reproducible identification of a clinically defined ultra-high-risk group is essential to guide translational research efforts in identifying the best targets for early intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Biostatistics Shared Resource Facility, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA196521-01.

Authorship

Contribution: V.W., E.M., S.L., and A.C. contributed to data acquisition, interpretation, and analysis; and all authors drafted and reviewed the manuscript, approved the final version, decided to publish this report, and have vouched for data accuracy and completeness.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ajai Chari, Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1470 Madison Ave, New York NY 10029; e-mail: ajai.chari@mountsinai.org.

References

- 1.Kyle RA, Remstein ED, Therneau TM, et al. . Clinical course and prognosis of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(25):2582-2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, et al. . International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(12):e538-e548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajkumar SV, Kyle RA. Haematological cancer: treatment of smoldering multiple myeloma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10(10):554-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsen JT, Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, Rajkumar SV. Serum free light chain ratio as a biomarker for high-risk smoldering multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2013;27(4):941-946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kastritis E, Terpos E, Moulopoulos L, et al. . Extensive bone marrow infiltration and abnormal free light chain ratio identifies patients with asymptomatic myeloma at high risk for progression to symptomatic disease. Leukemia. 2013;27(4):947-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waxman AJ, Mick R, Garfall AL, et al. . Classifying ultra-high-risk smoldering myeloma. Leukemia. 2015;29(3):751-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sørrig R, Klausen TW, Salomo M, et al. ; Danish Myeloma Study Group. Smoldering multiple myeloma risk factors for progression: a Danish population-based cohort study. Eur J Haematol. 2016;97(3):303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waxman AJ, Mick R, Garfall AL, et al. . Modeling the risk of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2015;29(3):751-753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajkumar SV, Larson D, Kyle RA. Diagnosis of smoldering multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):474-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rago A, Grammatico S, Za T, et al. ; Multiple Myeloma GIMEMA-Latium Region Working Group. Prognostic factors associated with progression of smoldering multiple myeloma to symptomatic form. Cancer. 2012;118(22):5544-5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravi P, Kumar S, Larsen JT, et al. . Evolving changes in disease biomarkers and risk of early progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(7):e454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernández de Larrea C, Isola I, Pereira A, et al. . Evolving M-protein pattern in patients with smoldering multiple myeloma: impact on early progression. Leukemia. 2018;32(6):1427-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dispenzieri A, Kyle RA, Katzmann JA, et al. . Immunoglobulin free light chain ratio is an independent risk factor for progression of smoldering (asymptomatic) multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(2):785-789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29(3):374-393. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uno H, Cai T, Tian L, Wei LJ. Evaluating prediction rules for t-year survivors with censored regression models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2007;102:527-537. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shtatland E, Kleinman K, Cain EM Model Building in PROC PHREG with automatic variable selection and information. Paper presented at Thirtieth Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. 10-13 April, 2005. Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rajkumar SV, Gupta V, Fonseca R, et al. . Impact of primary molecular cytogenetic abnormalities and risk of progression in smoldering multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2013;27(8):1738-1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neben K, Jauch A, Hielscher T, et al. . Progression in smoldering myeloma is independently determined by the chromosomal abnormalities del(17p), t(4;14), gain 1q, hyperdiploidy, and tumor load. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(34):4325-4332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobs JF, Tate JR, Merlini G. Is accuracy of serum free light chain measurement achievable? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54(6):1021-1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tate JR, Graziani MS, Mollee P, Merlini G. Protein electrophoresis and serum free light chains in the diagnosis and monitoring of plasma cell disorders: laboratory testing and current controversies. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2016;54(6):899-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terpstra WE, Lokhorst HM, Blomjous F, Meuwissen OJ, Dekker AW. Comparison of plasma cell infiltration in bone marrow biopsies and aspirates in patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1992;82(1):46-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chilosi M, Adami F, Lestani M, et al. . CD138/syndecan-1: a useful immunohistochemical marker of normal and neoplastic plasma cells on routine trephine bone marrow biopsies. Mod Pathology. 1999;12(12):1101-1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhodapkar MV. MGUS to myeloma: a mysterious gammopathy of underexplored significance. Blood. 2016;128(23):2599-2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]