Abstract

The purpose of this study was to add to our understanding of Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) in healthcare, and how After Action Reviews (AARs) can be utilized as a learning tool to reduce errors. The study focused on the implementation of a specific form of AAR, a post-fall huddle, to learn from errors and reduce patient falls. Utilizing 17 hospitals that participated in this effort, information was collected on 226 falls over a period of 16 months. The findings suggested that the use of self-guided post-fall huddles increased over the time of the project, indicating adoption of the process. Additionally, the results indicate that the types of errors identified as contributing to the patient fall changed, with a reduction in task and coordination errors over time. Finally, the proportion of falls with less adverse effects (such as non-injurious falls) increased during the project time period. The results of this study fill a void in the NDM and AAR literature, evaluating the role of NDM in healthcare specifically related to learning from errors. Over time, self-guided AARs can be useful for some aspects of learning from errors.

Keywords: Meetings, Learning, After-Action Reviews, High Reliability Organizations, Naturalistic Decision Making, Healthcare

As the complexity of work environments and the problems that employees face increase, so does the importance of understanding of Natural Decision Making (NDM). NDM focuses on how professionals or experts make decisions, particularly in environments that are complex, uncertain, and have ill-defined goals (Klein, 2008; Lipshitz, Klein, Orasanu, & Salas, 2001). Not surprisingly, NDM has been studied extensively in high-reliability organizations. High reliability organizations regularly maintain safe operations in turbulent, high-risk environments without serious errors (Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 2000). They promote mindful attention to detail as a means of preventing minor errors from evolving into large-scale failures (Weick & Roberts, 1993). Many, if not all, of the characteristics of NDM apply to high-reliability organizations, and therefore these organizations are an appropriate setting for studying NDM (Baran & Scott, 2010). One important example of a high reliability organization to which NDM can be applied is that of healthcare (Gore, Banks, Millward, & Kyriakidou, 2006).

NDM research in healthcare has focused on how good decisions are made by nurses and doctors, that is, how medical personnel use heuristics, experience, and prioritize informational cues (Currey & Botti, 2003; Denig, Witteman & Schouten, 2002). However, Gore et al. (2006) note that the application of NDM to healthcare can be challenging because NDM models “have yet to address the issue of decision making accuracy and, in particular, how to avoid error that could potentially have fatal consequences” (p. 932). They further call for NDM research that will evaluate errors, understand how errors occur, and how we can leverage learning in the process of decision making. The purpose of this article is to start to address the issues raised by Gore et al. (2006). Specifically, in this paper we will evaluate the role of a particular form of after action review (AAR) performed after a patient fall, and investigate the use and effectiveness of these AARs as a learning tool over time.

After Action Reviews and Debriefs

High-reliability organizations’ unique combination of complexity, hazards, and need for team cohesion makes it particularly difficult to predict – and subsequently train for – all possible contingencies (Allen, Baran, & Scott, 2010). As the complexity of work environments increases, so does the importance of practical experiential learning (Carroll, 1995). An after-action review (AAR), also called a debrief or huddle, is a professional dialogue after an event that focuses on performance standards and enables team members to identify what happened, why it happened, and how to prevent future incidents (United States Agency for International Development, 2006).

AARs have been used by the military and para-military organizations for decades. More recently, the use of AARs in other contexts has also increased (Zakay, Ellis, & Shevalsky, 2004). AARs are viewed as an important way to improve organizational learning (Ellis & Davidi, 2005). Specifically, AARs provide team members with the opportunity to analyze their own behavior, its contribution to the outcome, and any potential changes that may need to occur (Ellis, Mendel, & Nir, 2006).

Using AARs as a Decision Making and Learning Tool

Past research on AARs and debriefs suggests that teams that conduct AARs are more effective than those that do not (Baird, Holland, & Deacon, 1999; Downs, Johnson, & Fallesen, 1987; Ellis et al., 2006; Tannenbaum & Cerasoli, 2013). In fact, a recent meta-analysis suggests that team effectiveness can be enhanced by 20% when teams conduct AARs (Tannenbaum & Cerasoli, 2013). Tannenbaum and Cerasoli also found that using trained facilitators improved the effectiveness of AARs significantly compared to those conducted without a facilitator. However, Tannenbaum and Cerasoli indicated that not enough studies were conducted without the use of a facilitator. Further, they did not compare the type of facilitation used (in house or trained facilitator). During training or when teams are relatively stable, it is possible to have the leader or trainer function as the facilitator. However, the use of facilitators is not always possible. Further, the use of facilitators can be costly and inefficient due to the need to conduct AARs during normal operations. It is therefore critical to understand how to train teams to conduct their own AARs that result in effective learning. More recent work suggests that self-guided debriefs, that is, an AAR that is guided by the team using a detailed guide, can be effective (Eddy Tannenbaum, & Mathieu, 2013).

Recent research suggests three things are essential in order for an AAR to be an effective learning tool (Eddy et al., 2013). First, AARs should allow for data verification, feedback, and information sharing. Data verification and feedback allow for calibration of information. Eddy et al. specifically note that sharing task related information allows team members to quickly identify the correct approach. For judgment related information, improvement in performance is tied to the degree to which team members share and discuss the rationale for the decision. Finally, it is likely that coordination type tasks benefit from the information sharing inherent in the AAR. Second, the AAR should provide a framework that would allow team members to critically reflect on the event, challenge implicit assumptions, and understand why something is working or not working. Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) suggest that members of effective high reliability organizations engage in retrospective discussion that reflects a reluctance to oversimplify interpretations and fosters an error-friendly learning culture because it allows members to mindfully reflect not only on successes but also on mistakes and near misses. Third, AARs provide a framework for establishing common goals and future action plans to prevent similar occurrences in the future (DeChurch & Haas, 2008; West 1996). Eddy et al. (2013) note that all three components characterize effective AARs and lead to improved learning as a result.

Consistent with Weick and Sutcliffe’s (2007) discussion of retrospective learning and decision making concerning high reliability organizations, one important aspect of an AAR that leads to learning is accurate identification of errors that have occurred (Ellis et al., 2006). In the context of healthcare, this becomes particularly important, as errors can have significant negative consequences. Further, as Gore et al. (2006) suggested, NDM research, in form of understanding how AARs are carried out, should focus on understanding how errors occur and therefore how they can be prevented.

To help organizations identify types of errors and develop strategies to learn from such errors, MacPhail and Edmondson (2011) developed a taxonomy of errors, based upon the certainty of the work process and the independence of the work activity. They specifically identified three types of errors: task, judgment, and coordination errors. A task error occurs when an individual makes a mistake in completing a routine or well-understood segment of work. A judgment error follows an individual’s faulty judgment or decision made during a less routinized or familiar work activity. A coordination error arises when individuals fail to share necessary information with one another despite the familiarity of the work process and knowledge needed to complete the work. These types of errors have also been identified as Eddy et al. (2013) as important aspects for discussion in effective AARs.

Based upon MacPhail and Edmondson’s (2011) framework, the accurate identification of task, judgment, and coordination errors is a critical outcome of the AAR because learning from and correcting an error depends upon the nature of the error. For instance, they propose that individual training and regular performance monitoring may correct a task error, focused reflection and improving decision making skills in uncertain situations may address a judgment error, and a group discussion and the formation of a new standardized policy may correct a coordination error. In addition, as Eddy et al. (2013) suggest, different factors may facilitate the identification of these errors. It is this identification of errors and the decision to learn from the retrospective processes and near miss identification that occurs in AARs.

After Action Reviews in Healthcare

Effective use of AARs is particularly salient in healthcare where too often the response to an adverse event is resolved by seeking consensus and closure (and avoiding blame) as opposed to immediate learning by frontline staff and making decisions focused upon the development of a plan to prevent future similar events (Nicolini, Waring, & Mengis, 2011). Inpatient falls are a common, costly, and serious adverse event in hospitals (Healy & Scobie, 2007) that may benefit from the focused learning that can occur in AARs. Falls may impact patients’ quality of life and result in significant costs to patients and hospitals (Bates, Pruess, Souney, & Platt, 1995). Although falls are traditionally considered a nursing quality indicator, several recent research studies have suggested that interprofessional teams in which all members played an active role in fall risk reduction were successful in sustaining decreased fall rates (Barker, Kamar, Morton, & Berlowitz, 2009; Cameron et al., 2010; Jackson, 2010; Szumlas, Groszek, Kitt, Payson, & Stack, 2004; Von Renteln-Kruse & Krause, 2007).

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (Boushon, Nielsen, Quigley, Rutherford, Taylor, & Shannon, 2008) and the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (Degelau et al., 2012) identify post-fall huddles, a form of AAR, as a best practice and essential component of a hospitals’ fall risk reduction program. Post-fall huddles occur immediately after a patient fall, and may include various professionals (such as nurses, physical therapist and/or pharmacist) as well as the patient or family members. Despite the importance of AARs in general and post-fall huddles as a specific mechanism to improve patient safety, the literature on AARs and post-fall huddles has not answered some important questions. It is to some of these questions we now turn.

Implementing AARs Over Time

An important purpose of this study was to evaluate the use of post-fall huddles or AARs outside the training environment and outside the laboratory, and specifically as applied in a healthcare setting. Post-fall huddles differ from other forms of AARs in the fact that the team that convenes for the AAR is different at different points in time. The staff interacting with a patient may differ based on the time of day (shift) or location of the patient fall, availability of the family, whether the patient is able to participate in the post-fall huddle, and the availability of healthcare disciplines other than nursing; may all influence who participates in the post-fall huddle. This variability may have important implications for the adoption and use of post-fall huddles over time. Self-guided post-fall huddles require the team to initiate and continue to use the post-fall huddle, as there is no facilitator. Further, as the team composition changes, factors that may facilitate the use of post-fall huddles such as team cohesion may not necessarily be present (Ellis et al., 2010). Therefore, an important issue evaluated in this study was the use of post-fall huddles over time. If post-fall huddles are perceived by the hospital personnel to be effective, that is, if hospital personnel find that the post-fall huddle helps them to learn from previous mistakes, we expect the use of post-fall huddles to increase over time.

Hypothesis 1: The use of self-guided post-fall huddles will increase over time.

In addition to the continued use of post-fall huddles as an indicator of perceived learning, we were also interested in the more direct effect post-fall huddles had on errors. Using the classification suggested by MacPhail and Edmondson (2011), we anticipate that the type of errors most prevalent (as a proportion) as contributing to a patient fall will change over time. As teams conduct post-fall huddles, task errors, which are easily identified and corrected (Eddy et al., 2013; MacPhail & Edmondson, 2011) should be reduced over time. In addition, we wanted to determine whether accuracy of error classification improved over time as a result of learning. We would expect that if post-fall huddles are improving learning from the event, the classification of the errors will improve over time.

Hypothesis 2: The implementation of self-guided post-fall huddles will result in changes in the percent of task, judgment, and coordination errors contributing to a fall event over time.

Hypothesis 3: The implementation of guided post-fall huddles will result in improved accuracy in identifying task, judgment, and coordination errors over time.

Finally, an important indication of learning from decision making is improved performance. In the case of post-fall huddles, the outcome that would show the effectiveness of the post-fall huddles is that of a reduction in falls or reduced severity of the outcome of falls. In the study of patient falls, assisted falls are typically less likely to result in harm to the patient than unassisted falls. An assisted fall is defined as a fall where a patient begins to fall and is assisted to the ground by another person (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010). Similarly, the outcome of the fall, when it occurs, whether injury resulted or not, is an indicator of severity. Because of the learning that occurs in AARs and the decisions made that should improve team processes (Tannenbaum & Cerasoli, 2013), we expected that fall outcomes will be less severe over time with the implementation of post-fall huddles, resulting in fewer injurious and fewer unassisted falls over time.

Hypothesis 4: The implementation of guided post-fall huddles will be related to a reduction in the proportion of unassisted falls and a reduction in the proportion of injurious falls over time.

Method

Sample and Procedure

We examined patient fall event reports from 17 small rural Critical Access Hospitals in a Midwestern state. Critical Access Hospitals are located in rural areas, must be at least 35 miles from the next critical access or larger hospital, have no more than 25 inpatient beds, and have an annual average patient length of stay less than 4 days (Department of Health and Human Services, 2013). This category of hospitals was created in 1997 by the U.S. Government to ensure that citizens in rural areas have adequate access to healthcare and hospitals. These hospitals typically treat more routine healthcare conditions that require hospitalizations for residents living in the rural area where the hospital is located. Critical Access Hospitals comprise one fourth of all community hospitals in the U.S. Compared to larger hospitals, Critical Access Hospitals may benefit from activities concentrated on reducing patient fall risk because they: a) tend to assist a greater proportion of older adults and fall risk is highest among this population (Flex Monitoring Team, 2006; Rubenstein, 2006), b) have limited resources to implement quality improvement initiatives (Flex Monitoring Team, 2004), and, c) are less likely to have financial incentives to reduce falls (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services) and therefore fall reduction may be a lower priority. These 17 hospitals participated in a two-year study on reducing inpatient fall risk. One component of the project emphasized collecting patient fall event information on a standardized form. As part of the form, we asked hospital staff to conduct a post-fall huddle in which they reflected upon and learned from the errors that led to a patient fall, and identified interventions to reduce patient fall risk. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

We collected 226 patient fall event reports from the 17 hospitals (M = 13.29 per hospital, range 3-31) between August 2012 and November 2013. A hospital staff member completed a fall event report after a patient fall event occurred. A representative from each hospital forwarded a secure copy of each fall event report to the project research team. Fall event reports and post-fall huddle information were entered manually into an Access database and verified by a research team member. Questions about the fall event report or post-fall huddle were clarified via email or over the phone with a member of the respective hospital’s fall risk reduction team.

Measures

Post-fall huddle

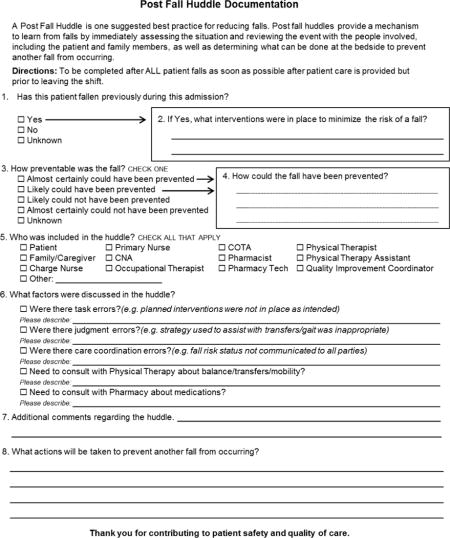

Staff in each of the hospitals were encouraged to conduct a self-guided post-fall huddle after each fall. The goal of the post-fall huddle was to identify and evaluate the situation and factors that led to a patient fall, and to determine what actions should be taken immediately to prevent another fall. A post-fall huddle form was created for this project by project personnel to guide the post-fall huddle (see Appendix A). At the time the project began none of the hospitals in the study had such a form and were not conducting post-fall huddles. The guide for completing a post-fall huddle was integrated as the last page of the fall event reporting form. This guide required personnel to provide descriptive information about the fall and the post-fall huddle such as, a) any previous patient falls during the current admission (yes or no), and if yes, a description of the interventions in place to minimize fall risk, b) the preventability of the fall (almost certainly could have been prevented to almost certainly could not have been prevented), and if likely or almost certainly could have been prevented, a description of how the fall could have been prevented, c) staff included in the huddle (patient, family/caregiver, charge nurse, primary nurse, certified nursing assistant, occupational therapist, certified occupational therapy assistant, pharmacist, pharmacy tech, physical therapist, physical therapy assistant, quality improvement coordinator, and/or other), d), additional comments regarding the huddle, and, e) description of changes to be made to reduce the patient’s fall risk.

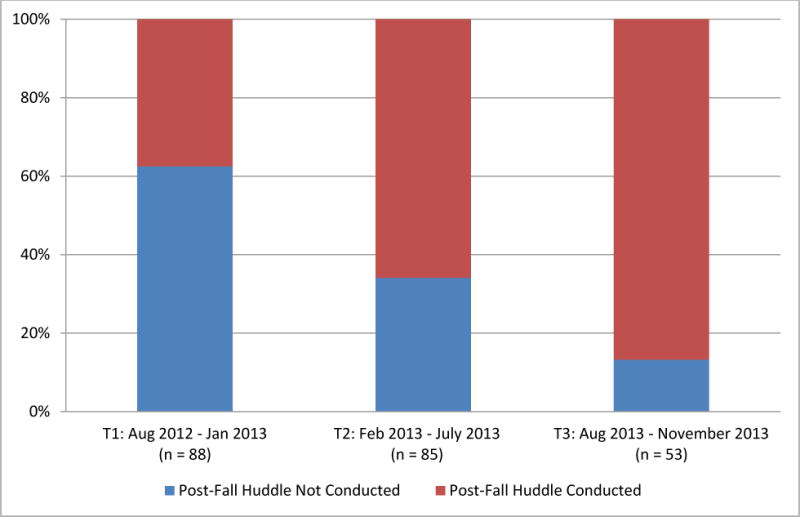

In addition, the type of error that led to the fall was described retrospectively and categorized based on the four learning domains developed by MacPhail and Edmondson (2011). The guide included a place to describe the error that occurred in detail, and a categorization into one of the domains. Recognition of the correct learning domain should structure the conversation and learning strategy during the post-fall huddle. The post-fall huddle form was typically completed by the nurse responsible for the patient that fell on the shift that the fall occurred. No information was gathered about who completed the form; however, the personnel attending the huddle and completing the form vary based on patient and time of fall. Thus, completion of the post-fall huddle form varied from fall to fall within the same hospital. Over the duration of the project, 41% (7) of the hospitals completed post-fall huddles for 80% or more of the reported falls. Another 41% (7) of the hospitals completed post-fall huddles for at least 50% of the falls. The final 18% (3) of the hospitals completed the post-fall huddle less than 50% of the time. While the majority of hospitals had moderate to high rates of completion, it was not uniform across the hospitals. The success rate in implementing the post-fall huddle varied by hospital; however, as the data illustrate (see Figure 1), the proportions of falls that included a post-fall huddle steadily increased over time. We operationalized the use of a post-fall huddle if the huddle form indicated two or more individuals (including the patient/family) participated in the huddle. Of the 226 reported falls, 59.7% (n = 135) had a corresponding post-fall huddle.

Figure 1.

Percent of 226 reported falls in which a post-fall huddle was conducted over three project time periods.

Errors contributing to a fall event

One component of the guided post-fall huddle included a discussion about the different types of errors that may have contributed to a patient’s fall. The error identification discussion was structured around three key learning domains: task, judgment, and coordination errors (MacPhail & Edmondson, 2011). A task error occurs when an individual makes an error in completing a routine or well-understood segment of work; for example, when a nurse fails to turn on a high fall risk patient’s bed alarm even though hospital policy requires the use of bed alarm for all high fall risk patients. A judgment error occurs when an individual performs a less familiar task that requires a degree of judgment or decision making; for example, when a nurse assistant decides to leave a patient with a cognitive impairment alone in a bathroom. A coordination error occurs when individuals fail to share necessary information with one another; for example, when a person responsible for transporting a patient to radiology was uninformed of the patient’s level of assistance needed during transfers.

A member of the project research team provided an independent evaluation of the task, judgment, and/or coordination errors that contributed to the fall, based upon the information provided in the fall event report and post-fall huddle guide. To establish inter-rater agreement, a second member of the project research team independently evaluated a random 10% sample of the errors that contributed to the fall (n = 16 falls), based upon the same information provided in the fall report and post-fall huddle guide. There was 87.5% agreement between the evaluators on the errors that contributed to the fall, suggesting acceptable inter-rater agreement on error evaluations.

We calculated the accuracy of task, judgment, and/or coordination error identification by comparing the response(s) hospital staff provided on the post-fall huddle form to the response(s) provided by the project research team. Accurate error identification was operationalized when the post-fall huddle team and the research team agreed on a type of error that precipitated a fall (note that each fall event could have multiple types of errors).

Type of patient fall

Fall event reports included two standardized items to help hospital staff categorize the type of fall. The first item addressed patient assistance during the fall. An assisted fall occurred if the patient was assisted by another person, such as a staff member, to the ground or a lower surface, and an unassisted fall occurred if the patient fell alone or was unattended to during the fall. The second item addressed whether or not the patient was injured (for example, suffered a skin tear, laceration requiring stitches, bruising, dislocation or fracture, head injury, or other type of injury) as a result of the fall.

Project time period

We examined implementation and outcomes of post-fall huddles over three time periods within the falls project: Time 1 = August 2012 to January 2013, Time 2 = February 2013 to July 2013, and Time 3 = August 2013 to November 2013. The two-year falls project began in August 2012, so these three time periods corresponded with 1-6, 7-12, and 13-16 months, respectively, into the project. Each time period provided hospitals with sufficient time to collect fall event reports, conduct post-fall huddles, and implement changes in their fall risk reduction programs, as well as provided sufficient number of falls in each time period to allow for analyses.

Analyses

We used chi-square analyses to test our hypotheses for potential trends in the use of guided post-fall huddles over time (Hypothesis 1), the percentage of task, judgment, and coordination errors contributing to a fall event over time (Hypothesis 2), huddle team accuracy in identification of task, judgment, and coordination errors over time (Hypothesis 3), and the reduction in unassisted and injurious falls over time (Hypothesis 4). Chi-square tests were used for two reasons. First, although the patient fall report and post-fall huddle data were nested within 17 hospitals, patient falls are a relatively rare event so there were small numbers of fall reports and subsequent post-fall huddles conducted within each hospital (both in total and over the three time periods). Second, the post-fall huddle and fall report data used in this study were categorical in nature (e.g., a post-fall huddle occurred, or not).

Results

Reported trends reflect changes over three time periods in the project, unless otherwise noted. The 17 hospitals presented varying post-fall huddle adoption rates, with some choosing not to conduct (or perhaps report) any post-fall huddles and others conducting a post-fall huddle for every reported fall. Overall, 59.7% (n = 135) of the 226 reported falls had a corresponding post-fall huddle, and approximately one-third of these huddle teams were interdisciplinary in nature (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Composition of Post-Fall Huddle Teams

| N | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing Onlya | 46 | 34.10% |

| Nursinga with Patient and/or Family | 45 | 33.30% |

| Interdisciplinaryb | 44 | 32.60% |

Note.

Nursing includes primary nurse, certified nursing assistant, and/or charge nurse.

Interdisciplinary includes representatives from at least two of the following disciplines: nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, pharmacy, quality improvement, and/or other noted discipline.

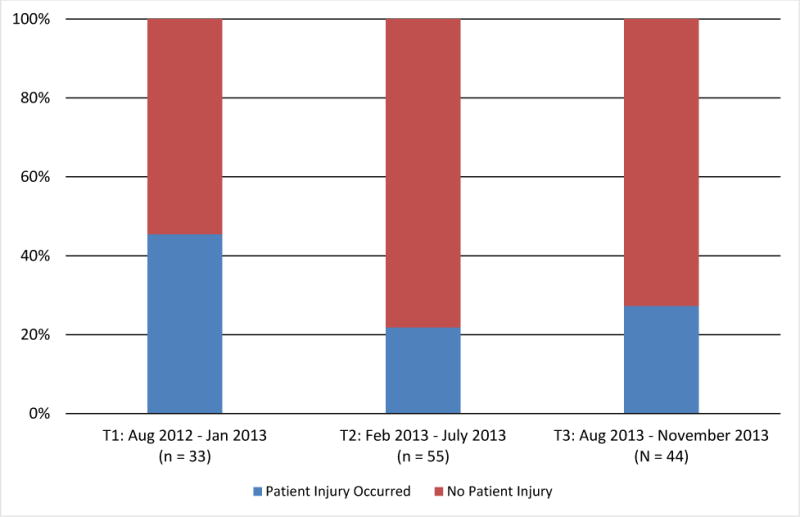

Hypothesis 1 suggested the use of self-guided post-fall huddles would increase over time. Our chi-square analysis indicated a significant relationship between the use of post-fall huddles and project time period, χ2 (2, N = 226) = 35.56, p < .001, (see Figure 1). Specifically, the proportion of fall events that included a post-fall huddle increased from less than 40% in Time 1 to over 80% in Time 3.

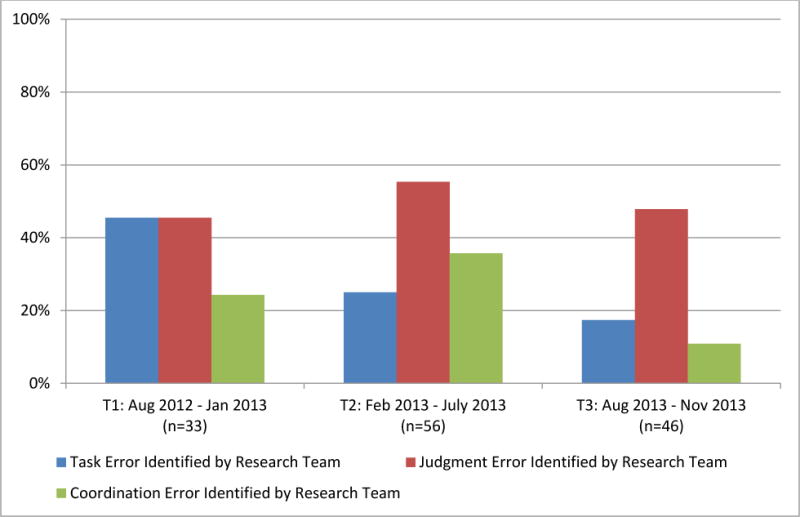

Hypothesis 2 proposed the implementation of self-guided post-fall huddles would result in changes in the percent of task, judgment, and coordination errors contributing to a fall event over time. Our chi-square analysis indicated a significant relationship between project time period and the percentage of task errors, χ2 (2, N = 135) = 7.89, p = .02, and coordination errors, χ2 (2, N = 135) = 8.44, p =.02, but not judgment errors, χ2 (2, N = 135) = 1.00, p = .61, based on the project research team determination of the errors contributing to a fall event (see Figure 2). Specifically, the percent of task errors contributing to a patient fall as identified by the research team decreased over the three project time periods, and coordination errors decreased from Time 2 to Time 3.

Figure 2.

Percent of task, judgment, and coordination errors identified by the project research team as contributing to a fall event over three project time periods.

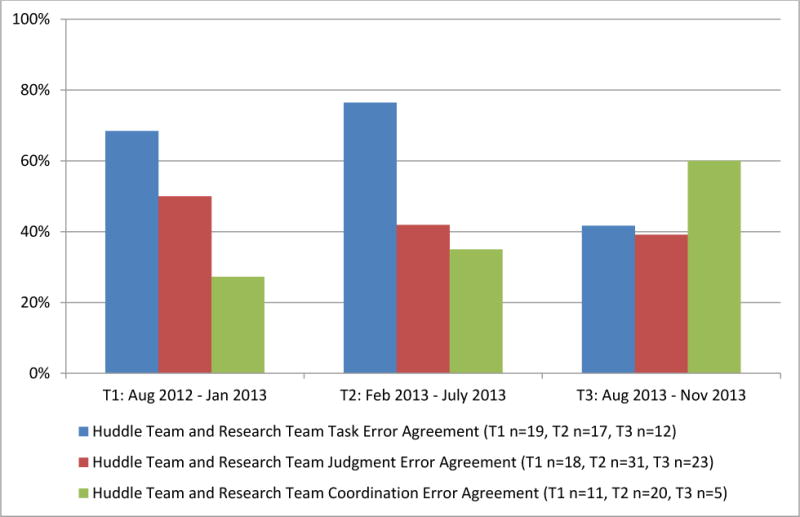

Hypothesis 3 suggested the implementation of guided post-fall huddles would result in improved accuracy in identifying task, judgment, and coordination errors over time. However, our chi-square analysis indicated no significant relationship between project time period and the accuracy of post-fall huddle teams’ identification of task, χ2 (2, N = 135) = 3.93, p = .14, judgment, χ2 (2, N = 135) = .51, p = .77, or coordination, χ2 (2, N = 135) = 1.62, p = .44, errors (see Figure 3). Although post-fall huddle teams’ accuracy in identifying errors did not increase over time, they did accurately identify nearly two-thirds of the task errors. However, less than half of the judgment errors, and just over one-third of the coordination errors that contributed to a fall were accurately identified by the post-fall huddle teams.

Figure 3.

Percent of accurate task, judgment, and coordination errors, in which the post-fall huddle team and project research team agreed contributed to a fall event, over three project time periods.

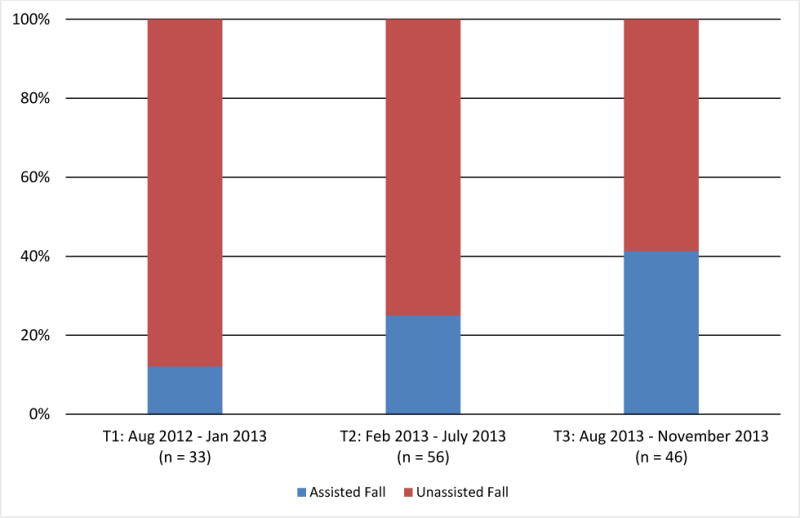

Finally, Hypothesis 4 proposed the implementation of guided post-fall huddles would related to a reduction of unassisted falls and injurious falls over time. Our chi-square analysis indicated a significant relationship between project time period and the percent of assisted falls in which a post-fall huddle was conducted, χ2 (2, N = 135) = 8.50, p = .01, (see Figure 4). Notably, the direction of the trend indicates increased proportion of assisted falls with post-fall huddles over the project duration. Further, there was a marginally significant relationship between project time period and the percent of injurious and non-injurious falls in which a post-fall huddle was conducted, χ2 (2, N = 135) = 5.70, p = .06, (see Figure 5). The results suggest there is a decrease in the number of injurious falls.

Figure 4.

Percent of reported assisted and unassisted falls with a post-fall huddle over three project time periods.

Figure 5.

Percent of reported injurious and non-injurious falls with a post-fall huddle over three project time periods.

Supplemental Analyses

Our hypotheses addressed the extent to which hospital staff implemented post-fall huddles and subsequent huddle learning outcomes over time. In an effort to understand the factors that may have led hospital staff to conclude that conducting a post-fall huddle was necessary to learn from the fall, we conducted additional analyses to explore if the severity of the outcome of the fall event for the patient related to the choice to use a post-fall huddle. We speculated that hospital staff may choose to conduct a post-fall huddle when the fall event was more adverse: unassisted compared to assisted, and resulted in injury compared to no injury. A chi-square analysis indicated no significant differences in the proportion of assisted and unassisted patient falls with a post-fall huddle, χ2 (2, N = 226) = .14, p = .71, and no significant differences in the proportion of injurious and non-injurious patient falls with a post-fall huddle, χ2 (2, N = 226) = 0, p = 1.00, Thus, the severity of patient fall was not related to the decision to conduct a post-fall huddle.

Discussion

As high-reliability organizations, healthcare institutions rely on the decision making expertise of their healthcare professionals to provide quality patient care and maintain a safe environment. The negative consequences of patient care errors can be significant, and potentially fatal. Thus, creating opportunities to help healthcare professionals identify errors, understand how errors occur, and identify strategies to prevent errors are critical to support learning and enhance NDM skills in an effort to sustain patient safety. In this paper, we evaluated the use and effectiveness of post-fall huddles, a specific form of an AAR (Allen, Baran, & Scott, 2010), as a tool to support learning and improve NDM practices over time.

The results of this study indicate that the use of guided post-fall huddles increased over time during the project. Initially over 60% of the falls did not include a post-fall huddle; by the last time period, less than 15% of the falls did not include a post-fall huddle. Given the difficulties associated with implementing a new process (which these post-fall huddles were), we suggest that one potential reason for the increase in use over time was the perceived usefulness. As hospital staff experienced the post-fall huddle, and realized its potential for learning and improving patient safety, the practice of conducting a post-fall huddle took hold.

Additionally, this study suggests that the types of errors identified in post-fall huddles as contributing to a patient fall may change over time. Specifically, the proportion of errors categorized as task and coordination errors decreased over time while the proportion of judgment errors may be increasing over time, suggesting that the benefit of the post-fall huddle in learning and preventing errors may be dependent on error type. However, hospital teams had more difficulty accurately identifying the various error types, suggesting a deficiency in the learning that was occurring from the post-fall huddle.

Finally, the results suggested that over time, the use of post-fall huddles increased for assisted falls and non-injurious falls. Early in the project, the majority of the post-fall huddles occurred for an event with more serious consequences (an unassisted fall, an injurious fall). However, over time, teams increasingly adopted the use of post-fall huddles as a tool to learn from falls with a less adverse outcome. We now turn our attention to the implications of all these findings for theory, research, and practice.

Theoretical Implications

This research begins to address Gore et al.’s (2006) call to extend the boundaries of traditional NDM healthcare research and examine how decision making accuracy may be improved through the evaluation of errors and their causes. Our work examined how guided post-fall huddles supported learning from errors. The integration of MacPhail and Edmondson’s (2011) error and learning domain taxonomy into the guided post-fall huddle encouraged huddle team members to identify and reflect upon the errors that contributed to an adverse patient event. As staff conducted these huddles after the adverse event occurred (i.e., after the fall and error(s) that led to the fall), this evaluation structure helped huddle teams establish a direct link between the error that occurred and the consequence of the error.

Although we found no significant improvements in the accurate identification of task, judgment, or coordination errors over time, the proportion of task errors decreased over time and huddle teams accurately identified nearly two-thirds of the task errors that contributed to a patient fall. This finding is consistent with the hospitals’ focus on conducting prospective audits of the interventions in place to reduce a patient’s risk of falling. The goal of such audits is to increase the reliable use of interventions to reduce fall risk as required by hospital policy, in effect identifying if staff conducted the tasks necessary to minimize fall risk. Such activities are consistent with the strategies MacPhail and Edmonson (2011) recommended to reduce the occurrence of task errors. Thus, as completing tasks became more reliable, staff errors were more likely to be due to poor decision making about processes that remained uncertain.

Further, this study adds to our understanding of how correcting different types of errors may be facilitated by the process of the post-fall huddle (McPhail & Edmonson, 2011). Task errors are more easily identified, and tend to be concrete; therefore, task errors may be more easily corrected once the team is aware of the error. Engagement in the post-fall huddle facilitated this awareness. Coordination errors are a result of limited or poor communication. The post-fall huddle facilitated communication between different professionals thus it is likely that the improved communication resulted in fewer coordination errors. Finally, judgment errors require deeper reflection. Although we expected our post-fall huddle guide to facilitate reflection, it is possible that the level of reflection attained was not deep enough or that the guidance provided by the form was not sufficient to fully uncover and address judgment errors. Future research should consider increasing the depth of reflection that occurs in AARs by potentially incorporating more questions or considering the use of facilitators. Further, when AARs are conducted by a facilitator, it is likely that the facilitator provides the guidance needed to improve communication, reflection, and discussion of errors, which in turn lead to the success of the AARs as a learning tool (Ellis et al., 2006). This suggests that when developing guided AARs, that understanding the nature of errors has important implications for how post-fall huddles, and AARs in general, should be conducted to increase learning and facilitate effective decision making.

This study is one of few that evaluate the use of a decision making debrief methodology and its spread of adoption over time. While studies show that debriefs are effective tools in improving performance (Tennanbaum & Cerasoli, 2013), the use of debriefs usually occurs because they are externally facilitated or required by the organization (Eddy et al., 2013). The post-fall huddle debrief in this study was facilitated internally and under conditions that may be more difficult for consistent implementation (such as changing team members). Our work adds to the research suggesting that self-guided AARs are useful and potentially inherently rewarding (Eddy et al., 2013), and therefore AAR use increased over the time period of the project. Further support for this is suggested by the finding that the type of event (more severe) had no effect on conducting the post-fall huddle, indicating that hospital staff found the post-fall huddle a useful learning tool.

Finally, a key theoretical implication of this study is the possibility that in some high-reliability organizations, the introduction of a guided AAR process may result in both the increase in occurrence of reflective processes as well as the reduction of undesirable outcomes. According to Weick and Sutcliffe (2007), attention to errors and near misses is a hallmark of high reliability organizations and one that suggests integrating an intervention that leads to increased awareness of risks would not only be desirable, but sought after. The current study confirms tenants of high reliability theory such that those organizations that are deliberately reflective about regular operations may see a significant decrease in the severity of the negative outcomes from the work. In this context it was a reduction in the proportion of unassisted falls as opposed to a reduction of falls generally. Thus, some negative events may be harder to avoid, but learning from them can and does still occur when reflective processes are in place (Eddy et al., 2013). Alternatively, it is also possible that organizations began to include more assisted falls in their reporting as the project progressed, potentially as a result of increased reflective processes from the guided AARs.

Practical Implications

The results of the study also have important practical implications for organizations in general, high-reliability organizations, and healthcare institutions. First, the study suggests that providing employees with an approach that facilitates discussion and reflection has a positive effect on organizational effectiveness and risk response. Implementing an organizational change is never easy, and the adoption of change is not a certain outcome (Rogers, 1995). This study indicates that self-guided AARs were adopted by the hospitals, suggesting that participants potentially perceived the AARs as useful and therefore continued to hold these meetings. Not only did employees adopt the process, employees implemented the process even when the outcome was not serious (non-injurious, assisted fall). Managers might consider adopting a self-guided AAR process for the purpose of reflection on recent events and regular operations.

Another important implication is that an AAR guide should be directly tied to the types of errors likely to occur, and that different errors call for different types of efforts. In other words, the AAR guide must match with the action that occurred and the types of reflective processes most needed for the improvement of the activities surrounding the action. Task errors are likely the easiest to identify and correct (McPhail & Edmondson, 2011). In this case, the mere discussion of the error is likely to be effective. When discussing task errors, teams are likely to discuss why the error occurred, and what can be done to prevent it in the future. In addition, awareness of these errors is likely to increase vigilance and attention, and therefore prevent the occurrence of similar errors in the future. However, judgment errors may require more in depth reflection and understanding of the decision processes that led to the judgment. They may also require multiple perspectives to facilitate discussion of potential alternatives.

Limitations and Future Directions

While the results of the study are encouraging and have important implications, this study is not without its limitations. First, patient falls are relatively rare events, and as a result we have a limited number of event reports in total and over the three project time periods. Further, these falls occurred across 17 different hospitals. Given the limited number of event reports received at the time of this study and the small sample of hospitals we could not account for this nesting in our analyses. The collection of additional fall event reports over time (as patient falls occur) will enable us to conduct more rigorous and robust analyses to investigate the effects post-fall huddles on learning and improved decision outcomes.

Second, because each of the 17 hospitals independently implemented the post-fall huddle program, the process and content of staff training to conduct huddles likely varied between hospitals: some hospitals may have stressed the importance of certain aspects of the guided huddle form more than others. Of significance to this study is the extent to which staff likely to participate in a huddle received adequate education regarding the three types of errors—task, judgment, and coordination. The extent of this education may have affected some huddle teams’ ability to accurately identify certain types of errors, and the resulting actions taken to reduce the patient’s risk of a subsequent fall. This issue is further complicated by the fact that staff engage in a post-fall huddle only after a fall event occurred, and patient falls are a relatively uncommon event. As mentioned earlier, conducting effective AARs is a learned skill, and the learning outcomes of such reflective activities are likely to improve with training and practice (Eddy et al., 2013). Future research should examine how the extent and degree of training on how to conduct an effective post-fall huddle, or AAR in general, even when self-guided, improves the quality of the huddle process and subsequent learning outcomes.

Third, due to their very nature, post-fall huddles that analyze unassisted falls may contain inferences because hospital personnel may not have been present for the fall. Therefore, the description of the unassisted fall event may include assumptions about what likely occurred rather than what was actually observed. During assisted falls, hospital personnel were there to assist, so a nurse or other employee was able to observe directly the fall event. However, in many cases, this may not influence the important aspects of the post-fall huddle. Take for example, a fall that occurred while the patient was using the rest room. If the patient is noted as a fall risk patient, it is likely the case that he or she should not be allowed in the rest room alone. The exact details of how the fall occurred are less important than the fact that the patient was alone when he or she should not have been. Additionally, as the proportion of assisted falls increased, the cases for which limited details were known also decreased (i.e. more occasions where personnel were present when falls occurred).

Fourth, the post-fall huddle guide may not have adequately supported the reflection necessary to identify and learn from judgment errors. Post-fall huddle teams may struggle to identify judgment errors for a number of reasons. As suggested by Eddy et al. (2013), AARs should focus on reflection, information sharing, data verification and recalibration. Our post-fall huddle guide, as provided in the huddle form, focused on information sharing and data verification, more so than on reflection. As a result, it may have been easier for post-fall huddle teams to identify task and coordination errors. Task errors are more directly tied to verification that standard practices and protocols were in place, whereas coordination errors are tied to the identification of information sharing issues among staff. MacPhail and Edmondson (2011) suggest that improvement in judgment is tied to the degree to which team members with diverse backgrounds and relevant expertise reflect upon, share, and discuss the rationale for the decision. Structuring a portion of the guided huddle around the identification of the potential novelty and relative uncertainty of the situation may help teams to identify instances of poor judgment. Encouraging staff to seek out those with expertise or experience in similar circumstances may also facilitate learning from the error. Dissemination of these lessons learned may lessen the uncertainty within the context of a certain decision and reduce the likelihood of future similar errors.

Finally, an important issue is whether the use of post-fall huddles is sustainable. The data from this study indicate that the use of post fall huddles increased over time, suggesting sustainment. It is not clear however, whether the use of post-fall huddles will continue without the expectation of completion of the form for the purpose of the project. We plan to follow up with these same hospitals in the future to determine whether they are continuing to use the post-fall huddle.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to evaluate the implementation of post-fall huddles, a special case of AAR, in a sample of small rural hospitals. Of particular interest was the role of post-fall huddles in facilitating learning from errors, as a form of naturalistic decision making. This study suggests that teams adopted post-fall huddles, and that post-fall huddles had some effect on learning, as the proportion of falls that included a post-fall huddle increased, indicating adoption. Further, learning can be inferred from the decrease in proportion of falls with more severe outcomes (unassisted, injurious). However, the post-fall huddles implemented did not increase accuracy of error classification, indicating that learning to accurately categorize the errors did not occur. These results indicate that self-guided AARs can be used as a learning tool, but attention must be paid to the guide and its development, ensuring that the AAR is tailored to the type of errors teams are likely to encounter.

Practitioner Points.

Team effectiveness can increase by as much as 20% with the effective use after-action reviews.

A self-guided after-action review tool can be implemented and increase in use overtime for some organizations.

After-action reviews appear to improve the detection of certain types of errors thus generally improving organizational operations and future decision making.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by grant number R18HS021429 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Appendix A

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Fall Event Description. 2010 Retrieved from https://www.psoppc.org/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=ecb65e93-db36-417f-882e-30fcfe2c0321&groupId=10218.

- Allen JA, Baran BE, Scott CW. After-action reviews: A venue for the promotion of safety climate. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2010;42:750–757. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird L, Holland P, Deacon S. Learning from action: Imbedding more learning into the performance fast enough to make a difference. Organizational Dynamics. 1999;27:19–32. doi: 10.1016/S0090-2616(99)90027-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baran BE, Scott CW. Organizing ambiguity: A grounded theory of leadership and sensemaking within dangerous contexts. Military Psychology. 2010;22:42–69. doi: 10.1080/08995601003644262. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barker A, Kamar J, Morton A, Berlowitz D. Bridging the gap between research and practice: Review of a targeted hospital inpatient fall prevention programme. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2009;18:467–472. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.025676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates DW, Pruess K, Souney P, Platt R. Serious falls in hospitalized patients: Correlates and resource utilization. The American Journal of Medicine. 1995;99:137–143. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)80133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boushon B, Nielsen G, Quigley P, Rutherford P, Taylor J, Shannon D. Transforming care at the bedside how-to guide: Reducing patient injuries from falls. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron ID, Murray GR, Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Hill KD, Cumming RG, Kerse N. Interventions for preventing falls in older people in nursing care facilities and hospitals. Cochrane Database System Review. 2010;1:CD005465. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005465.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JS. Incident reviews in high-hazard industries: sense making and learning under ambiguity and accountability. Organization & Environment. 1995;9:175–197. doi: 10.1177/108602669500900203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital-acquired conditions (present on admission indicator) Retrieved from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/HospitalAcqCond/index.html?redirect=/HospitalAcqCond/

- Currey J, Botti M. Naturalistic decision making: A model to overcome methodological challenges in the study of critical care nurse’s decision making about patients’ hemodynamic status. American Journal of Critical Care. 2003;12:206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Dreu CKW. Team innovation and effectiveness: The importance of minority dissent and reflexivity. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2002;11:285–298. doi: 10.1080/13594320244000175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeChurch LA, Haas CD. Examining team planning through an episodic lens: Effects of deliberate, contingency, and reactive planning on team effectiveness. Small Group Research. 2008;39:542–568. doi: 10.1177/1046496408320048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Degelau J, Belz M, Bungum L, Flavin PL, Harper C, Leys K, Lundquist L, Webb B. Prevention of falls (acute care) Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement; 2012. Retrieved from https://www.icsi.org/_asset/dcn15z/Falls.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Denig P, Witteman CLM, Schouten HW. Scope and nature of prescribing decision made by general practitioners. British Medical Journal Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2002;11:137–143. doi: 10.1136/qhc.11.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services. Critical access hospital rural health fact sheet series. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/CritAccessHospfctsht.pdf.

- Downs CW, Johnson KM, Fallesen JJ. Analysis of feedback in after action reviews. Kansas University Lawrence Communications Research Center; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gore J, Banks A, Millward L, Kyriakidou O. Naturalistic decision making and organizations: Reviewing pragmatic science. Organizational Studies. 2006;27:925–942. doi: 10.1177/0170840606065701.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy ER, Tannenbaum SI, Mathieu JE. Helping teams to help themselves: Comparing two team led debriefing methods. Personnel Psychology. 2013;66:975–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S, Davidi I. After-event reviews: Drawing lessons from successful and failed experience. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005;90:857–871. doi: 10.1037/0021-010.90.5.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S, Ganzach Y, Castle E, Sekely G. The effect of filmed versus personal after-event reviews on task performance: The mediating and moderating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2010;95:122–131. doi: 10.1037/a0017867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis S, Mendel R, Nir M. Learning from successful and failed experience: The moderating role of kind of after-event review. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91:669–680. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flex Monitoring Team. (Flex Monitoring Team Briefing Paper).Critical Access Hospital patient safety priorities and initiatives: Results of the 2004 national CAH survey. 2004;(3) [Google Scholar]

- Flex Monitoring Team. (Flex Monitoring Team Briefing Paper).Analysis of CAH inpatient hospitalizations and transfers: Implications for national quality measurement and reporting. 2006;(13) [Google Scholar]

- Healey F, Scobie S. The third report from the patient safety observatory: Slips, trips, and falls in the hospital. London, England: National Patient Safety Agency; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SS. Fall prevention takes ‘constant attention,’ comprehensive interventions. Hospital Peer Review. 2010;35:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein G. Naturalistic decision making. Human Factors. 2008;50:456–460. doi: 10.1518/001872008X288385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipshitz R, Klein G, Orasanu J, Salas E. Taking stock of naturalistic decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. 2001;14:331–352. doi: 10.1002/bdm.381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacPhail LH, Edmondson AC. Learning domains: The importance of work context in organizational learning from error. In: Hofmann DA, Frese M, editors. Errors in Organizations. New York: Routledge; 2011. pp. 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolini D, Waring J, Megnis J. Policy and practice in the use of root cause analysis to investigate clinical adverse events: Mind the gap. Social Science and Medicine. 2011;73:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orasanu J, Connolly T. The reinvention of decision making. In: Klein GA, Orasanu J, Calderwood R, Zsambok CE, editors. Decision making in action: Models and methods. Westport, CT: Ablex; 1993. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Reason J. Managing the risks of organizational accidents. Aldershot, England: Ashgate; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. Free Press; NewYork: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein LZ. Falls in older people: Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing. 2006;35:37–41. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlas S, Groszek J, Kitt S, Payson C, Stack K. Take a second glance: A novel approach to inpatient fall prevention. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety. 2004;30:295–302. doi: 10.1016/s1549-3741(04)30033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum SI, Cerasoli CP. Do team and individual debriefs enhance performance? A meta-analysis. Human Factors. 2013;55:213–245. doi: 10.1177/0018720812448394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Agency for International Development. After-action review: Technical guidance. 2006 Feb; Retrieved from pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADF360.pdf.

- van Ginkel W, Tindale RS, van Knippenberg D. Team reflexivity, development of shared task representations, and the use of distributed information in group decision making. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2009;13:265–280. doi: 10.1037/a0016045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- von Renteln-Kruse W, Krause T. Incidence of in-hospital falls in geriatric patients before and after the introduction of an interdisciplinary team-based fall-prevention intervention. Journal of The American Geriatric Society. 2007;55:2068–2074. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE, Sutcliff KM. Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. 2nd. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM, Obstfeld D. High reliability: The power of mindfulness. Leader to Leader. 2000;2000:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE, Roberts KH. Collective mind in organizations: Heedful interrelating on flight decks. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1993;38:357–381. doi: 10.2307/2393372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- West MA. Reflexivity and work group effectiveness: A conceptual integration. In: West MA, editor. Handbook of work group psychology. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1996. pp. 555–579. [Google Scholar]

- Zakay D, Shmuel E, Shevalsky M. Outcome valence and early warning indicators as determinants of willingness to learn from experience. Experimental Psychology. 2004;51:150–157. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169.51.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]