Abstract

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury can result in joint instability, decreased functional performance, reduced physical activity and quality of life and an increased risk for post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Despite the development of new treatment techniques and extensive research, the complex and multifaceted nature of ACL injury and its consequences are yet to be fully understood. The overall aim of the NACOX study is to evaluate the natural corollaries and recovery after an ACL injury.

Methods and analysis

The NACOX study is a multicentre prospective prognostic cohort study of patients with acute ACL injury. At seven sites in Sweden, we will include patients aged 15–40 years, within 6 weeks after primary ACL injury. Patients will complete questionnaires at multiple occasions over the 3 years following injury or the 3 years following ACL reconstruction (for participants who have surgical treatment). In addition, a subgroup of 130 patients will be followed with clinical examinations, several imaging modalities and biological samples. Data analyses will be specific to each aim.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the regional Ethical committee in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 2016/44-31 and 2017/221–32). We plan to present the results at national and international conferences and in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Participants will receive a short summary of the results following completion of the study.

Trial registration number

Keywords: knee, musculoskeletal disorders, magnetic resonance imaging, sports medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The prospective observational design with frequently monitored biological, psychological and social variables allows analysis of outcomes at key, clinically relevant time points after injury.

Quantitative methods are used to assess the perspectives of important stakeholders in acute anterior cruciate ligament injury management (patients and clinicians (orthopaedic surgeons and physiotherapists)).

The utilisation of advanced imaging techniques and collection of biological samples for identification of proxies of early osteoarthritis that can be related to prospectively collected patient-reported outcome measures and clinical data.

Loss to follow-up and missing data may be a risk due to the extensive collection of patient-reported outcomes. However, we have a dedicated study monitoring team and a rigorous data analysis plan to appropriately deal with the missing data.

Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are common in young athletes. In Sweden, there are approximately 7000 new injuries per year representing approximately 0.81/1000 inhabitants aged 10–64 years.1 Despite the extensive research to identify the best treatment algorithms, there are still many patients who report unsatisfactory outcomes regarding knee stability, activity level and QoL following ACL injury.2 3 This may be because research has tended to focus on single factors, rather than accounting for the multifactorial nature of injury and recovery. There is also a clinical dogma that ACL reconstruction is necessary for a successful outcome after ACL injury and to resume sporting activities.4 5 Although there is evidence that some patients have functional disability fulfilling the clinical indications for ACL reconstruction,6 with high quality rehabilitation, many patients achieve satisfactory knee function and participation in sports without surgery.7 8

An ACL injury has biological, psychological and social corollaries9 that directly affect the patient (eg, impaired QoL and lower physical activity participation) and may affect the community (eg, increased health utilisation costs, impaired productivity, potential for increased chronic disease burden through flow-on development of non-communicable diseases associated with physical inactivity such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes). Taking a biopsychosocial approach, factors including the extent of the initial injury (eg, whether there were other knee structures involved), factors directly related to the treatment (eg, which intervention and when) and patient preferences, expectations and past experiences may all be relevant when assessing outcomes.

The most serious long-term corollary after ACL injury is the increased risk for post-traumatic osteoarthritis, estimated to be up to 50% by 15 years after injury.3 This risk of developing osteoarthritis is higher if the ACL injury is associated with a meniscus tear, and there are conflicting results regarding whether having ACL reconstruction reduces or increases the risk of osteoarthritis.4 5 10–12 The underlying mechanisms behind the development of osteoarthritis are not well understood. Altered biological processes due to injury and joint bleeding, concomitant structural injuries to the cartilage and the subchondral bone and joint instability and subsequent altered biomechanics may be relevant for the development of osteoarthritis. Secondary joint trauma (eg, with additional meniscal tears or ACL reconstruction13) may also influence the risk for osteoarthritis.

Outcomes need to be evaluated from both the patient’s and the clinician’s perspective. Patient-reported outcomes provide important insights into aspects of injury and recovery that cannot otherwise be observed or measured with clinical tests or imaging.14 Clinical outcomes provide the clinician (and by extension—in a well applied shared decision-making approach—the patient) with feedback regarding the effects of different clinical decisions on injury (ie, which treatment and when) and any physical changes that occur following a clinical decision (eg, change in effusion and muscle strength, incidence of new injuries, development of osteoarthritis).

The short-term aim of ACL injury management is to achieve satisfactory knee function and physical activity participation. In the long term, treatment should aim to reduce the risk of developing osteoarthritis. Satisfaction is complex and short-term success (eg, returning to pivoting sports) may facilitate longer term failure (eg, developing osteoarthritis after sustaining a second or third meniscal injury). From the patient’s perspective, satisfaction can relate to both the outcome of management of the injury (including knee function, confidence to participate in physical activity, fulfilment of expectations for recovery) and to the process of healthcare delivery (including being an active participant in the decision-making process, communication with clinicians, information about the injury and treatment).15–18 The clinician needs to monitor the resolution of impairments (knee stability, symmetrical lower limb muscle strength, absence of knee effusion) to ensure that treatment is tailored so that the patient has the physical capacity to reach his or her expectations (eg, return to sport, return to occupation).19 However, it is evident that these criteria cover only some of the spectrum of possible corollaries of ACL injury.

There is evidence that treatment after ACL injury needs to be individualised.20 The clinician needs to be able to account for and (ideally) address the important biological, psychological and social factors for each patient. However, we still lack evidence regarding which factors, for which patient, at which time and this poses challenges for clinical practice. Therefore, to enhance understanding of the consequences of ACL injury and improve treatment, the overall aim of the NACOX study is to investigate the natural corollaries and recovery after ACL injury. Understanding the complexity of the consequences of ACL injury may improve clinical decision-making to ensure best healthcare for patients.

To achieve the overall aim, there are five main study objectives.

To assess biological, psychological and social factors and their relationships to the natural corollaries and recovery after acute ACL injury.

To evaluate the choice of treatment after acute ACL injury (ie, ACL reconstruction (ACLR) or non-ACL reconstruction (non-ACLR)).

To evaluate the return to sport after acute ACL injury.

To study knee problems in the short and long term after acute ACL injury.

To identify proxies (biomarkers and structural risk factors) for early detection of symptomatic and radiographic osteoarthritis.

Methods and analysis

This study is a prospective multicenter prognostic cohort study. Patients will be consecutively recruited over approximately 20 months, from up to seven sites (mix of public and private healthcare clinics) in Sweden.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All patients with acute knee trauma presenting to the identified clinics are potentially eligible for participation.

Inclusion criteria: patients with an ACL injury, sustained no more than 6 weeks prior to presentation, and aged between 15 and 40 years at time of ACL injury.

Exclusion criteria: previous ACL injury/ACL reconstruction on the same knee, serious concomitant knee injury (eg, posterior cruciate ligament rupture, fracture that requires separate treatment), inability to understand written and spoken Swedish language, cognitive impairments, other illness or injury that impairs function (eg, fibromyalgia, rheumatic diseases and other diagnoses associated with chronic pain).

Procedure

Recruitment of participants started in October 2016, and this study does not alter the usual course of treatment for patients with ACL injury at recruiting centres. This process is as follows.

Patient receives a clinical diagnosis from an orthopaedic surgeon, verified by MRI, within 2–6 weeks after their knee injury.

Initial treatment according to a supervised rehabilitation programme of approximately 3 months duration.21

Scheduled follow-up after approximately 3 months, where further treatment is decided on between patient and orthopaedic surgeon.

Consequently, patients of this cohort will follow one of the two following pathways: (1) ACLR plus postoperative supervised rehabilitation and (2) supervised rehabilitation alone (non-ACLR).

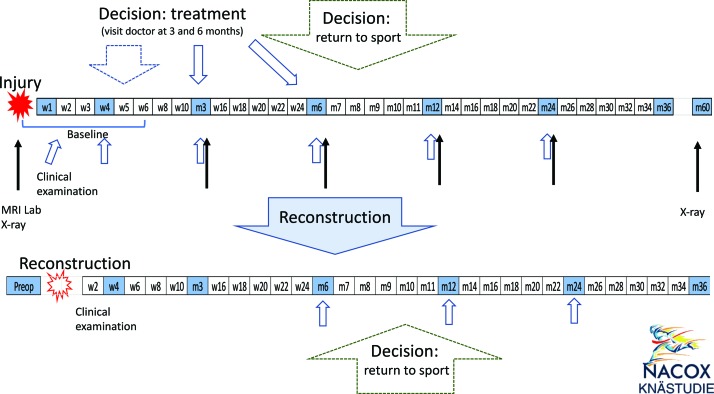

Patients will receive information about the study at their initial contact with the healthcare provider. Subsequently, a member of the research team will contact the patient by phone to provide additional verbal information and obtain verbal consent. Patients who accept participation will be asked to sign a written informed consent form before questionnaires are sent via smartphone or e-mail. Questionnaires will be sent weekly for the first 6 weeks, fortnightly from week 7 to week 24, monthly from month 7 to month 12 and bi-monthly from year 1 to year 3 after initial injury. Questionnaire length varies from very short (10 questions, approximately 2 min completion time) to longer at specific critical time points (figure 1 and table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the NACOX study follow-up plan. w1, w2 and m3, m6, etc, denote weeks or months after injury or reconstruction. Each box denotes when a questionnaire will be sent; shaded boxes indicate extended questionnaires. Time points for clinical examination (blue arrows), MRI, lab and X-rays (black arrows) are indicated. Baseline questionnaire, clinical examination, MRI, lab and X-rays are within 6 weeks after the injury.

Table 1.

MRI, radiographic assessment and collection of biological samples over the study period for patients recruited at the Linköping site

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months | 60 months | |

| Weight-bearing radiographs | X | – | – | – | – | X |

| Full clinical protocol | X* | – | – | – | – | |

| Compositional protocol | X | X | X | X | – | – |

| Explorative protocol | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Blood | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Urine | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Joint fluid† | X |

*Bilateral assessment.

†Collection will be performed under anaesthesia at the time of any surgery during follow-up.

A questionnaire about treatment choice (ACLR or non-ACLR) is completed by the patient, orthopaedic surgeon and physiotherapist at the time the decision for ACLR or non-ACLR is made. A questionnaire about the decision to return to sport is completed by the patient and the physiotherapist when the patient reports that he/she is back to full participation in the goal sports/physical activity. For patients with ACLR, a new baseline questionnaire will be completed at the time of reconstruction. Subsequent data collection will continue according to the new baseline time point (figure 1).

One subgroup (approximately 130 patients recruited from Linköping) will have extended follow-up data collection at baseline and 3, 6, 12 and 24 months after injury. At these time points, a clinical examination will be completed by a physiotherapist, physical activity will be registered over five consecutive days using a triaxial accelerometer (activPAL, PAL Technologies, UK), knee MRI will be performed and blood and urine samples will be collected. A joint fluid sample is acquired at baseline if indicated due to joint effusion and at the time of any additional surgery including ACLR (if the patient has surgical treatment). Weight bearing radiographs are done at baseline and 5 years follow-up. Patients who have ACLR are followed up with questionnaires and clinical examination with new baseline at the time of reconstruction. MRIs and blood and urine samples are followed up with the injury according to the index baseline (figure 1). Additional verbal and written consent for collection of biological samples and imaging is obtained prior to any data collection.

Outcomes

Reflecting a biopsychosocial approach, outcome measurement for this study will evaluate four main aspects: patient-reported outcomes, physical function, physical activity and physiological markers of joint injury (figure 1).

Patient-reported outcomes: all study participants

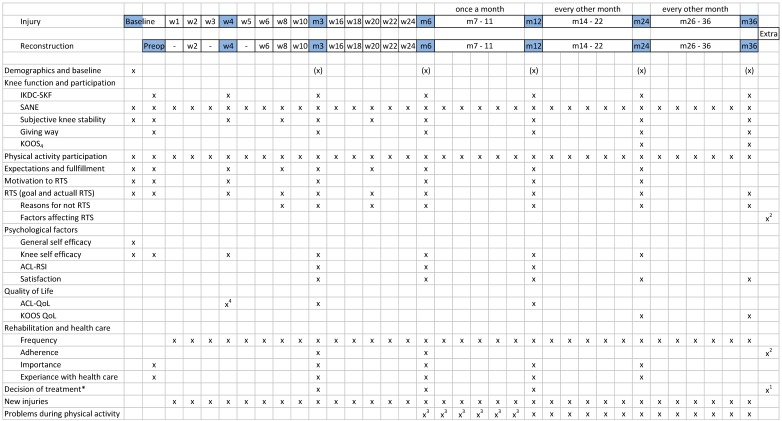

Demographic and baseline characteristics including age, sex, BMI, smoking habits, occupation, preinjury activity level, medical and injury history, sick leave, preferences regarding treatment will be collected with the baseline questionnaire (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Reported outcomes at different time points after injury or reconstruction. KOOS4, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, subscales for pain, symptoms, function in sport and recreation and knee-related quality of life; RTS, return to sport; *, answered by the patient, orthopaedic surgeon and physiotherapist; (X), only some questions are asked during these time points; 1, question answered when the decision for ACLR is made; 2, question answered by the patient and physiotherapist when the patient has returned to full sports participation; 3, assessed only for non-ACLR; 4, only the subscales ‘life style’ and ‘social and emotional’ of the ACL-QoL; QoL, quality of life.

Patient-reported knee function and participation will be assessed with the International Knee Documentation Committee Subjective Knee Form (IKDC-SKF),22 a Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) of global knee function23 and the four subscales of Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS4) (pain, other symptoms, function in sport and recreation (sport/rec) and knee-related QoL).24 Subjective knee stability during ACL and sports will each be assessed with a single numeric rating scale (1–10 scale) (figure 2).

The frequency of self-reported participation in physical activity will be collected according to the recommendations from Swedish National Board of Welfare. Participants will report the type of physical activity they participated in (eg, football, strength training) and the level of participation (eg, recreational, elite) during the previous week. Participation in up to three activities can be recorded (figure 2).25

Expectations for recovery (two questions) and fulfilment of expectations (one question) will be assessed using six-item Likert scales. Participants will be asked to indicate if their goal was to return to sport and reasons for not returning. Motivation to return to the preinjury physical activity will be evaluated using a questionnaire we developed based on the transtheoretical model of behaviour change (figure 2).18

The General Self Efficacy Scale will be used at baseline to assess the individual’s beliefs that his/her actions determine successful outcome.26 Knee-specific self-efficacy will be assessed with the subscale of the Knee Self Efficacy Scale that evaluates patients’ perception of future knee function (four questions).27 Psychological readiness for return to sport will be assessed with the ACL-Return to Sport after Injury questionnaire that includes questions on confidence in performance, emotions and risk appraisal.28 Satisfaction with present knee function will be evaluated with a seven-item Likert scale ranging from ‘delighted’ to ‘terrible’.29 Knee-related QoL will be assessed with the ACL-QoL questionnaire and KOOS QOL (figure 2).30

Participants will be asked to indicate the number of rehabilitation sessions they have completed. Adherence to rehabilitation will be assessed by the patient and physiotherapist with the Sports Injury Rehabilitation Adherence Scale.31 The importance of rehabilitation for the current knee function will be assessed on a five-response scale ranging from ‘necessary for my current knee function’ to ‘not necessary at all’.32 Experience with healthcare will be assessed with a five-item Likert scale ranging from ‘very good’ to ‘very bad’ (figure 2).

Information about new knee injuries will be collected using a direct question, which is followed up with phone call if the injury is severe, that is, results in functional limitation during the following days or inability to participate in physical activity. Knee problems during physical activity participation will be assessed with the knee-specific part of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) questionnaire (figure 2).33

Clinical examination: subgroup of study participants

The subgroup of participants recruited from one of the study sites (Linköping) will have clinical examinations of knee function, performed by an orthopaedic surgeon together with a physiotherapist (always for the baseline assessment), or physiotherapist alone or physiotherapy student in the final year of education. All assessors will have standardised training in the clinical examination procedure.

Knee status will be assessed using knee joint effusion (circumference of the joint using a measurement tape and the ‘stroke test’),34 knee joint laxity tests (Lachman test, Lever sign, anterior drawer and medial/lateral laxity), knee flexion and extension and ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, varus or valgus knee alignment. Instrumented knee laxity measurements will be assessed using the KT-1000 arthrometer at 133N and manual maximum (mean value of three repetitions).

Functional performance will be evaluated through qualitative assessment of gait (10 m walking test), single leg squat and four single-limb hop tests (single hop for distance, triple hop, crossover hop and 6-metre timed-hop).35 Postural control will be assessed using a single-limb static balance task with eyes closed (SOLEC). Concentric quadriceps and hamstrings strength will be assessed using a Biodex isokinetic dynamometer, at 60°/s (five repetitions) and 180°/s (15 repetitions) angular velocities.

Activity registration: subgroup of study participants

At the conclusion of the clinical examination, participants will be asked to wear a triaxial accelerometer (activPAL micro, PAL Technologies) for a minimum of 5 days (maximum 7 days) immediately following the examination. The accelerometer will be attached mid-way between the hip and the injured knee according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Imaging: subgroup of study participants

Patients recruited in Linköping (approximately 130 patients) will undergo extensive imaging assessment and collection of biosamples.

Plain weight-bearing radiographs is the current gold standard for assessment of radiographic osteoarthritis and will be obtained using a slightly modified method of the Lyon-Schuss view (participants stand, bearing equal weight through each limb36) and a standardised axial patellofemoral joint view (table 1).37

MRI will be obtained from both knees at baseline for diagnostic purposes, to confirm an acute ACL tear in the index knee and to examine the status of the contralateral knee. At follow-up, only the index knee will undergo MR image acquisition. MR images will be acquired using a Philips Ingenia 3T scanner with a 16-channel knee coil and will be obtained at baseline, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months (table 1).

For clinical evaluation and diagnostics, the normal clinical protocol at the Linköping site will be followed (scan time 15 min, table 2).

Table 2.

Detailed description of MRI sequences.

| Clinical package | Sagittal Proton Density (PD), 3 mm slice thickness with 0.3 mm gap. TE=20 ms; TR=1800 ms, ETL 10; FOV 160×145, ACQ matrix 516×384=0.31×0.38 mm, recon matrix 528. Scan time 2:58 min. |

| Axial PD FatSat, 3 mm slice thickness with 0.3 mm gap. TE=35 ms; TR=3981 ms, ETL 15; FOV 140×140, ACQ matrix 332×330=0.42×0.42 mm, recon matrix 512. Scan time 4:15 min | |

| Sagittal PD FatSat, 3 mm slice thickness with 0.3 mm gap. TE=30 ms; TR=3400 ms, ETL 15; FOV 160×145, ACQ matrix 468×399=0.31×0.40 mm, recon matrix 528. Scan time 3:56 min. | |

| Coronal PD FatSat, 3 mm slice thickness with 0.3 mm gap. TE=30 ms; TR=3572 ms, ETL 16; FOV 160×140, ACQ matrix 516×332=0.31×0.42 mm, recon matrix 528. Scan time 3:56 min | |

| PD FS 3D | Sagittal PD FatSat 3D, 0.63 mm slice thickness, TE=185, TR=1300, ETL=63, FOV=144×162, AQC matrix 228×226=0.63×0.63, recon matrix 448. Scan time 6:31 min |

| T2map | Sagittal T2-map (T2 relaxation), 3 mm slice thickness with 0.3 mm gap. TE=n*10 ms; TR=2371 ms, ETL 8; FOV 160×140, ACQ matrix 456×280=0.35×0.50 mm, recon 560. Scan time 5:53 min |

| T1Rho | 3D sagittal spin lock (T1Rho relaxation), 4 mm slice thickness. Spin lock time (1, 10, 20 and 40 ms), (TE=3.3 ms; TR=6.4 ms, ETL 64; FOV 140×140, ACQ matrix 280×268=0.50×0.52 mm, recon 352. Scan time 2:36 min |

| Qmap | Sagittal Qmap (T1 relaxation, T2 relaxation, PD), 3 mm slice thickness with 0.3 mm gap. TE=8.8/110 ms; TR=4217 ms, ETL 16; FOV 160×145, ACQ matrix 364×270=0.40×0.59 mm, recon 576. Scan time 6:19 min |

ACQ, Acquisition; ETL, Echo Train Length; FOV, Field of View; TE, Echo Time; TR, Repetition Time.

For bone shape analyses, a 3D PD sequence (scan time 6.5 min, table 2) will be obtained.

For compositional analysis of cartilage and menisci, sagittal T2maps and T1Rho will be obtained (scan time approximately 16 min, table 2).

For exploratory purposes, a new in-house developed sequence (Qmap) with the potential of reducing clinical and compositional scan time and adding explorative measures of T1 maps T2 maps and PD maps will be obtained (scan time approximately 6 min, table 2).38

Collection and storage of biological samples: subgroup of study participants

All samples will be stored in a dedicated biobank at −70°C.

Joint fluid (haemarthrosis) will be aspirated from the index knee at baseline to ascertain joint bleeding (highly indicative of severe knee injury) according to clinical routine. Due to the pain and discomfort associated with knee joint arthrocentesis (especially in knees without effusion), additional longitudinal collection of joint fluid will only be performed in case of surgical procedure (collection will be during surgery). Collected samples will be centrifuged at 2500g for 10 min and aliquoted into 0.7 mL tubes for storage.

Venous blood samples will be collected at the same visit as image acquisition. Collected samples will be centrifuged and aliquoted according to a specific protocol for storage.

Urine samples will be collected at first morning void (preferred). Collected samples will be centrifuged at 1800g for 10 min and aliquoted into 1.0 mL tubes for storage at −70°C.

Analyses will include, but are not limited to, those presented in table 3. In addition, several markers of inflammation, such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, tumour necrosis factor-α, interferon-γ, will be analysed.

Table 3.

Planned analyses of biomarkers.

| Biomarker | Fluid | Process | Tissue |

| ARGS-aggrecan | Serum Synovial fluid |

Cartilage turnover | Cartilage |

| CTX-II | Urine | Type II collagen degradation | Cartilage Bone |

| CTX-I | Serum Urine |

Bone turnover | Bone |

| COMP | Serum Synovial fluid |

Cartilage degradation | Cartilage |

| C2C | Serum Urine |

Type II collagen degradation | Cartilage |

| NTX-I | Serum Urine |

Bone resorption | Bone |

ARGS-aggrecan, the aggrecanase generated aggrecan neoepitope with amino acids alanine, arginine, glycine, serine; C2C, type II collagen epitope C2C; COMP, Cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, also known as thrombospondin-5; CTX-II, C-terminal crosslinking telopeptide type II collagen; NTX-I, N-terminal crosslinking telopeptide type I collagen.

Decision-making for choice of treatment and return to sport

Factors affecting the decision of choice of treatment (ACLR or not) will be evaluated by the patient, orthopaedic surgeon and physiotherapist with questionnaires. Respondents will answer questions about why the particular treatment was chosen, if they perceive it was the right treatment choice, the agreement for choice of treatment between the clinicians and patient, about the patient’s involvement and understanding of information and about the communication between clinicians. The physiotherapist and patient also answer questions about patient rehabilitation.

Factors affecting the decision for return to sports is evaluated at the time the patient replies that she/he is back to full sports participation of the goal sport/physical activity (with or without knee problems) based on the response to a question from the OSTRC questionnaire33 (‘have you had any difficulties participating in your sport activity due to your knee problems’ with the response ‘full participation without or with knee problems’). Other questions capture the areas on how the decision for return to sport was taken, possible criteria used to approve return to sport, activity and participation modification.

Primary outcomes and statistical analyses

A suite of analyses is planned for each of the five main study objectives.

Study objective A: assessment of the biological, psychological and social factors and their relationships to the natural corollaries and recovery after acute ACL injury

Specific aims

Assess whether there is a relationship between knee status and self-reported function early (up to 8 weeks) following ACL injury and the IKDC-SKF at 3 and 12 months follow-up.

Assess whether there is a relationship between knee status in the first 8 weeks following injury and functional performance at 12 months follow-up.

Evaluate how physical activity, self-reported activity participation or as measured by activPAL, in the first 8 weeks after ACL injury is related to self-reported function and functional performance at 3 and 12 months after injury.

Investigate the prognostic relationship between returning to physical activity after ACL injury and key biological, psychological and social factors.

Primary outcome

Self-reported physical activity participation and IKDC subjective knee score at 12 months follow-up.

Secondary outcomes

Functional performance at 3, 6, 12 and 24 months follow-up, time to return to the goal physical activity.

Statistical analysis

We will use generalised estimating equations (GEE) to assess longitudinal relationships between knee status and subjective knee function. The outcome variable will be IKDC subjective knee form score. Predictor variables may include knee joint effusion, laxity and range of motion and SANE.

We will use GEE to assess longitudinal relationships between knee status and functional performance. The outcome variables will be measures of hopping performance, strength and postural control. Predictor variables may include knee joint effusion, laxity and range of motion and SANE.

We will use multilevel modelling to assess relationships between physical activity and knee status. The outcome variable will be IKDC subjective knee form score. Predictor variables may include physical activity (self-reported and objectively measured), knee status (extent of index injury (ie, concomitant injuries), knee joint effusion, laxity and range of motion), age and sex.

We will use multilevel modelling to assess the prognostic relationship between returning to the goal physical activity and biopsychosocial factors. The outcome variable will be time to return to the goal physical activity. The predictor variables will be different biopsychosocial factors (collected with questionnaires and clinical examination). We will use factor analysis to guide which independent variables are entered into the model.

Study objective B: evaluation of the choice of treatment after ACL injury

Specific aims

Describe factors that are important for the choice of treatment after an ACL injury, that is, ACLR or non-ACLR, from patients, orthopaedic surgeons’ and physical therapists’ perspective.

To confirm the factors identified as important for treatment choice, using demographic and patient-reported data.

Assess the relationship between factors (biological, psychological, social factors and factors that affected the choice of treatment) and satisfactory knee function (IKDC subjective knee form) at 12 months.

Describe the decision-making process for treatment and evaluate patient satisfaction with the decision that was made.

Primary outcomes

Satisfaction with the treatment choice and the relationship to patient-reported outcome (IKDC) at 12 months after injury or ACLR.

Secondary outcomes

Factors affecting treatment decision.

Statistical analysis

We will summarise the treatment decision factors reported by patients and clinicians descriptively using frequency tables. We will confirm whether specific treatment factors exist for individual patients, by matching the patient’s own demographic and/or patient-reported data to the relevant factor.

We will use factor analysis to determine the common constructs underlying the factors that are important for the choice of treatment. The smaller number of related groups of factors will be used in a subsequent multivariable model. We will run separate analyses for the factors cited as important for the decision for ACLR and the factors cited as important for the decision for non-ACLR.

Finally, we will use a multilevel model to estimate the relationship between biopsychosocial factors and self-reported knee function at 12 months. The outcome variable will be IKDC subjective knee form score at 12 months. The predictor variables may include clusters of biopsychosocial factors (identified in A—assessment of the biological, psychological and social factors and their relationships to the natural corollaries and recovery after acute ACL injury) and treatment choice clusters (independent variables). The model will be adjusted for treatment received (ie, ACLR or non-ACLR).

Study objective C: evaluation of return to sport after ACL injury

Specific aims

Describe the decision-making process for return to sport following ACL injury.

Describe the criteria physiotherapists use in clinical practice to clear patients to return to sport after ACL injury.

Validate the criteria used to clear patients to return to sport after ACL injury.

Primary outcome

Return to sport rate at 24 months follow-up.

Secondary outcomes

Time to return to sport, sports participation rates over time, incidence of new knee injuries.

Statistical analysis

We will summarise the return to sport decision factors reported by patients and clinicians descriptively using frequency tables. We will also summarise the criteria used by clinicians to decide when the patient was ready to return to sport descriptively using frequency tables. To assess the discriminant validity of the criteria used to clear patients to return to sport after ACL injury, we will use logistic regression analyses to compare relevant outcomes (eg, strength, effusion, range of motion) between participants who do and do not return to sport.

Study objective D: knee problems in the short term and long term after acute ACL injury

Specific aim

Describe the rate and nature of knee problems (new acute knee injury, gradual onset knee injury and osteoarthritis) after index ACL injury.

Assess whether there is a relationship between biological, psychological and social factors and new knee problems after acute ACL injury.

Primary outcome

New acute knee injury.

Secondary outcomes

Gradual onset knee injury, osteoarthritis.

Statistical analysis

We will use a time-to-event analysis to estimate the rate of new acute knee injuries (may include new ACL tears, new meniscus tears), the rate of radiographic osteoarthritis and the rate of symptomatic osteoarthritis. The predictor variables may include concomitant injury to other knee structures at index ACL injury, treatment (ACLR or non-ACLR), sex, age and clusters of biopsychosocial factors (identified in A—assessment of the biological, psychological and social factors and their relationships to the natural corollaries and recovery after acute ACL injury).

We will use a multilevel modelling approach to assess whether there is a relationship between biopsychosocial factors and gradual onset knee injuries. The independent variables may include clusters of biopsychosocial factors (identified in ‘assessment of the biological, psychological and social factors and their relationships to the natural corollaries and recovery after acute ACL injury’), treatment, sex and age.

Study objective E: identification of proxies for early detection of osteoarthritis

Specific aims

Identify imaging-based proxies of early radiographic and symptomatic osteoarthritis.

Identify change in specific local and/or systemic molecular biomarkers (biological proxies) and investigate their relation to imaging-based structural change and patient-relevant outcomes.

Investigate the temporal relation between symptoms, structure and biology after knee injury.

Primary outcome

Radiographic osteoarthritis at 5 years follow-up.

Secondary outcomes

MR-defined at 2 years follow-up; symptoms as defined by IKDC subjective knee form and SANE at 2 and 5 years follow-up.

Statistical analysis

We will use a multilevel modelling approach to relate predictor variables that may include imaging-based and biologically based proxies, and possible risk factors (eg, concomitant injury to other knee structures at index ACL injury, treatment (ACLR or non-ACLR), new meniscus injury, activity participation) to the primary and secondary outcomes. We will adjust for potential confounders that may include sex, age and body mass index.

Sample size calculation

For regression analysis in the different parts, using approximately 10 independent variables for each outcome, at least 130 participants will be included.39 For parts B and C, evaluating decision for treatment and RTS, we need geographically spread collected data in order to be generalisable. Since there might be different routines and common praxis among different clinics even in the same geographical area, it is important to include different clinics when collecting data. We are collecting data from seven different counties, and several clinics within these counties, spreading from south to north of Sweden. We expect to collect data regarding decision-making from at least about 25 orthopaedic surgeons (about 10% of all surgeons performing ACL reconstructions over Sweden) and at least 45 physiotherapists (there is no registry for the number of physiotherapists treating ACL-injured patients in Sweden).

Patient and public involvement

Participants will receive a short summary of the results following completion of the study.

Timeline

Patient recruitment started in October 2016 and will continue until October 2018.

Ethics and dissemination

Being included in this study will not influence which treatment the patient will receive. The study is approved by the regional Ethical committee in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 2016/44-31 and 2017/221–32).

Results will be presented at national and international conferences and submitted for publication to peer-reviewed journals. Participants will receive short summary of the study.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JK wrote the first draft and coordinated the preparation of the protocol together with CA. HG, HTG, MH, AS and RF were responsible for different parts of the protocol writing. All authors revised and accepted the final manuscript of the protocol.

Funding: This work is supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (VR 2015-03687), the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science (CIF P2016-0063 and P2017-0151), the Medical Research Council of Southeast Sweden FORSS (FORSS -662081) and the Medical Faculty at Linkoping University, Sweden.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethical Committee in Linköping, Sweden.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: Michael A Bowes (Sr Director Clinical Applications, Imorphics Ltd, Manchester, UK), Victor Casula (PhD, Research Unit of Medical Imaging, Physics and Technology, University of Oulu, Finland), Anna Fahlgren (Associate Professor, Experimetell Ortopedi, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University, Sweden), Anne Fältström (Physiotherapist, PhD, Region Jönköping County, Rehabilitation Centre, Ryhov County Hospital, Jönköping), Johan Kihlberg (Radiograph, Center for Medical Image Science and Visualization (CMIV), Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Sweden), Barbro Krevers (Associate Professor, Division of Health Care Analysis, Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Sweden), Maria Lindblom (MD Center for Medical Image Science and Visualization (CMIV), Department of Radiology, Linköping University, Sweden), Per Magnusson (Adjunct Professor, Clinical Chemistry, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Linköping University, Sweden), Miika Nieminen (Professor, Research Unit of Medical Imaging, Physics and Technology, University of Oulu, Finland, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Oulu University Hospital, Finland), Anders Persson (Professor, Center for Medical Image Science and Visualization (CMIV), Department of Medical and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Sweden).

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Michael A Bowes, Victor Casula, Anna Fahlgren, Anne Fältström, Johan Kihlberg, Barbro Krevers, Maria Lindblom, Per Magnusson, Miika Nieminen, and Anders Persson

References

- 1. Frobell RB, Lohmander LS, Roos HP. Acute rotational trauma to the knee: poor agreement between clinical assessment and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2007;17:109–14. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2006.00559.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Grindem H, Eitzen I, Engebretsen L, et al. . Nonsurgical or surgical treatment of acl injuries: knee function, sports participation, and knee reinjury: the delaware-oslo acl cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:1233–41. 10.2106/JBJS.M.01054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lohmander LS, Englund PM, Dahl LL, et al. . The long-term consequence of anterior cruciate ligament and meniscus injuries: osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1756–69. 10.1177/0363546507307396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ajuied A, Wong F, Smith C, et al. . Anterior cruciate ligament injury and radiologic progression of knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:2242–52. 10.1177/0363546513508376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanders TL, Kremers HM, Bryan AJ, et al. . Is anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction effective in preventing secondary meniscal tears and osteoarthritis? Am J Sports Med 2016;44:1699–707. 10.1177/0363546516634325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frobell RB, Roos HP, Roos EM, et al. . Treatment for acute anterior cruciate ligament tear: five year outcome of randomised trial. BMJ 2013;346:f232 10.1136/bmj.f232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grindem H, Eitzen I, Moksnes H, et al. . A pair-matched comparison of return to pivoting sports at 1 year in anterior cruciate ligament-injured patients after a nonoperative versus an operative treatment course. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:2509–16. 10.1177/0363546512458424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Österberg A, Kvist J, Dahlgren MA. Ways of experiencing participation and factors affecting the activity level after nonreconstructed anterior cruciate ligament injury: a qualitative study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2013;43:172–83. 10.2519/jospt.2013.4278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ardern CL, Kvist J, Webster KE. Psychological aspects of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Oper Tech Sports Med 2016;24:77–83. 10.1053/j.otsm.2015.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chalmers PN, Mall NA, Moric M, et al. . Does ACL reconstruction alter natural history?: A systematic literature review of long-term outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:292–300. 10.2106/JBJS.L.01713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nordenvall R, Bahmanyar S, Adami J, et al. . Cruciate ligament reconstruction and risk of knee osteoarthritis: the association between cruciate ligament injury and post-traumatic osteoarthritis. a population based nationwide study in Sweden, 1987-2009. PLoS One 2014;9:e104681 10.1371/journal.pone.0104681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Øiestad BE, Engebretsen L, Storheim K, et al. . Knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1434–43. 10.1177/0363546509338827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Larsson S, Struglics A, Lohmander LS, et al. . Surgical reconstruction of ruptured anterior cruciate ligament prolongs trauma-induced increase of inflammatory cytokines in synovial fluid: an exploratory analysis in the KANON trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017;25:1443–51. 10.1016/j.joca.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis JC, Bryan S. Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) have arrived in sports and exercise medicine: Why do they matter? Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1545–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2014-093707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Graham B, Green A, James M, et al. . Measuring patient satisfaction in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:80–4. 10.2106/JBJS.N.00811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ardern CL, Österberg A, Sonesson S, et al. . Satisfaction with knee function after primary anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is associated with self-efficacy, quality of life, and returning to the preinjury physical activity. Arthroscopy 2016;32:1631–8. 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Engstrand C, Kvist J, Krevers B. Patients' perspective on surgical intervention for Dupuytren’s disease - experiences, expectations and appraisal of results. Disabil Rehabil 2016;38:2538–49. 10.3109/09638288.2015.1137981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sonesson S, Kvist J, Ardern C, et al. . Psychological factors are important to return to pre-injury sport activity after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: expect and motivate to satisfy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017;25:1375–84. 10.1007/s00167-016-4294-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lynch AD, Logerstedt DS, Grindem H, et al. . Consensus criteria for defining ’successful outcome' after ACL injury and reconstruction: a Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort investigation. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:335–42. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Filbay SR, Roos EM, Frobell RB, et al. . Delaying ACL reconstruction and treating with exercise therapy alone may alter prognostic factors for 5-year outcome: an exploratory analysis of the KANON trial. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1622–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahldén M, Kvist J, Samuelsson K, et al. . [Individualized therapy is important in anterior cruciate ligament injuries]. Lakartidningen 2014;111:1440–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tigerstrand Grevnerts H, Grävare Silbernagel K, Sonesson S, et al. . Translation and testing of measurement properties of the Swedish version of the IKDC subjective knee form. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2017;27:554–62. 10.1111/sms.12861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shelbourne KD, Barnes AF, Gray T. Correlation of a single assessment numeric evaluation (SANE) rating with modified Cincinnati knee rating system and IKDC subjective total scores for patients after ACL reconstruction or knee arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:2487–91. 10.1177/0363546512458576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roos EM, Roos HP, Ekdahl C, et al. . Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)-validation of a Swedish version. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1998;8:439–48. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1998.tb00465.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Grindem H, Eitzen I, Snyder-Mackler L, et al. . Online registration of monthly sports participation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: a reliability and validity study. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:748–53. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-092075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Löve J, Moore CD, Hensing G. Validation of the Swedish translation of the General Self-Efficacy scale. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1249–53. 10.1007/s11136-011-0030-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomeé P, Währborg P, Börjesson M, et al. . A new instrument for measuring self-efficacy in patients with an anterior cruciate ligament injury. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2006;16:181–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2005.00472.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kvist J, Österberg A, Gauffin H, et al. . Translation and measurement properties of the Swedish version of ACL-Return to Sports after Injury questionnaire. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2013;23:568–75. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01438.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Street JH, et al. . Predicting poor outcomes for back pain seen in primary care using patients' own criteria. Spine 1996;21:2900–7. 10.1097/00007632-199612150-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mohtadi N. Development and validation of the quality of life outcome measure (questionnaire) for chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:350–9. 10.1177/03635465980260030201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kolt GS, Brewer BW, Pizzari T, et al. . The Sport Injury Rehabilitation Adherence Scale: a reliable scale for use in clinical physiotherapy. Physiotherapy 2007;93:17–22. 10.1016/j.physio.2006.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fältström A, Hägglund M, Kvist J. Factors associated with playing football after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in female football players. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2016;26:1343–52. 10.1111/sms.12588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clarsen B, Myklebust G, Bahr R. Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology: the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) overuse injury questionnaire. Br J Sports Med 2013;47:495–502. 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sturgill LP, Snyder-Mackler L, Manal TJ, et al. . Interrater reliability of a clinical scale to assess knee joint effusion. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2009;39:845–9. 10.2519/jospt.2009.3143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reid A, Birmingham TB, Stratford PW, et al. . Hop testing provides a reliable and valid outcome measure during rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther 2007;87:337–49. 10.2522/ptj.20060143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Brandt KD, Mazzuca SA, Conrozier T, et al. . Which is the best radiographic protocol for a clinical trial of a structure modifying drug in patients with knee osteoarthritis? J Rheumatol 2002;29:1308–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Boegård TL, Rudling O, Petersson IF, et al. . Joint space width of the tibiofemoral and of the patellofemoral joint in chronic knee pain with or without radiographic osteoarthritis: a 2-year follow-up. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:370–6. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00030-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Warntjes JB, Leinhard OD, West J, et al. . Rapid magnetic resonance quantification on the brain: Optimization for clinical usage. Magn Reson Med 2008;60:320–9. 10.1002/mrm.21635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tabatchnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th edn MA: Allyn & Bacon: Needham Heights, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.