Abstract

Objective

To estimate the economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients in Tanzania from 2005 to 2015.

Design

A retrospective review of data.

Setting

Tanzania Food and Drugs Authority and premises dealing with importations and distributions of pharmaceuticals.

Eligibility criteria

Confiscation reports of substandard human medicines, falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Quantities and costs of pharmaceutical products, costs of transportation, storage, court cases and disposal of products.

Results

The economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients was estimated at US$16.2 million, that is, value of substandard medicines US$13.7 million (84.4%), falsified medicines US$0.1 million (1%), cosmetics with banned ingredients US$1.3 million (8%) and other/operational costs US$1.1 million (6.6%). Some of the identified substandard and falsified human medicines include commonly used antibiotics such as phenoxymethylpenicillin, amoxicillin, cloxacillin and co-trimoxazole; antimalarials such quinine, sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, sulfamethoxypyrazine–pyrimethamine and artemether–lumefantrine; antiretroviral drugs; antipyretics and vitamins among others.

Conclusion

The economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients represent a relatively large loss of scarce resources for a poor country like Tanzania. We believe that the observed increase in the quantities and the economic cost of these products over time could partly be due to the improvement in the regulatory capacity in terms of human resources, infrastructure and frequency of inspections.

Keywords: health economics, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study from a low-income country to use national representative data to estimate the economic cost of poor-quality medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients over a 10-year period.

We were able to identify the manufactures of substandard medicines and purported manufacturers for falsified medicines which enabled us to isolate those whose products were more frequently found in the market.

Some data, particularly for cosmetics, were poorly recorded which made it difficult to apply the proper costing approach of identification, quantification and valuation.

We could not determine the reasons for the increase in quantities and cost over time, but we believe this could be due to increased availability of data because of improved regulatory capacity and public awareness, as opposed to an absolute increase in the amount of poor-quality medicines and cosmetics.

We were not able to include patient and health system costs for morbidities and mortalities associated with the use of poor-quality medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients; hence, the study underestimates the actual economic cost.

Introduction

In June 2012, customs officials in Luanda-Angola seized a cargo with about 1.4 million packets of fake Coartem (artemether–lumefantrine) hidden in loudspeakers. The cargo originated from Guangzhou in southern China, and the amount of fake antimalarials was estimated to be enough to treat more than half of all annual malaria cases in Angola.1 This example highlights the problem of substandard and falsified medicines (defined in box 1) and its potential public health impact. Substandard and falsified medicines represent about 10% of all medicines sold in low-income and middle-income countries.2 Expenditure on these products in low-income and middle-income countries is estimated at US$30.5 billion.2 Falsified medicines represent one of the most lucrative criminal business and is estimated to be worth between US$75 and US$200 billion.3

Box 1. Definitions of substandard medicines and falsified medicines.

Substandard medicines

According to WHO, these are genuine medicines that are authorised by the national medicines authorities, but which fails to meet national or international quality standards or specifications.

Falsified medicines

According to WHO, these represent deliberately and fraudulently labelled medicines with respect to identity, composition and source, and may include products with the correct or wrong ingredients, without active ingredients, with insufficient active ingredients or with fake packaging.20

The use of substandard and falsified medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients can have a tremendous negative impact on patient’s health, that can range from serious harm to treatment failure that can lead to severe illness and death. It is estimated that between 90 000 and 200 000 malaria deaths could be prevented if all antimalarials were genuine.4 5 Subtherapeutic plasma levels due to poor-quality medicines are strongly associated with emergence of antimicrobial resistance,6 7 hence increasing costs of treatment by switching from cheap first-line medicines to more expensive second-line medicines. The pharmaceutical industry is also a victim of falsified medicines, with annual losses estimated at €45 million which consequently reduces investments in innovative research and development.8

Low-income countries are the prime targets of substandard and falsified medicines because regulatory agencies and law enforcement systems are relatively weak, accompanied by poorly regulated markets and scarcity and/or erratic supply of basic medicines.9 10 Porous borders and complex supply-chain system of pharmaceuticals also contribute to the problem. There is scarcity of national-level data from low-income countries despite all evidences pointing towards an increasing problem of substandard and falsified medicines. Therefore, the objective of this study was to estimate the economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines including cosmetics with banned ingredients in Tanzania from 2005 to 2015.

Methods

This costing study used an ingredient approach to estimate the economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients between 2005 and 2015. This method involves identification, quantification and valuation of individual items. Costing was done from the perspective of the regulatory authority and the pharmaceutical distributors. We did not include patient and health system costs because of scarcity of data on morbidities and mortalities likely to be caused by the use of these products.

Sources of data

We used data from the regulatory authority and the major importers and distributors of pharmaceuticals from 2005 to 2015. The regulatory authority usually keeps all the confiscation reports for poor-quality medicines and banned cosmetics that are collected during routine inspections of premises and major operations. The report usually contains among other information, the name of the premise, generic and brand names of the product, strength, physical description of the package and products, batch number, manufacturing and expiry dates, and the quantities and sometimes an estimated value. Premises usually remain with the signed copy of the confiscation report. In this study, we retrieved all the confiscation data that were available at the regulatory authority’s headquarter and from its zonal offices. We also used confiscation report forms from the importers and distributors of pharmaceuticals to complement data from the regulatory authority. This means, in case the report forms were not filed at the regulatory authority, copies that were available at the importers and distributors offices were used. We were careful to avoid double counting. We also conducted a series of structured interviews with some officials at the regulatory authority, and the importers and distributors of pharmaceuticals to estimate operational cost incurred in the process of confiscation, withdraw of products from the market, storage, disposal and proceedings of court cases. Unregistered medicines do not undergo evaluation and approval by the regulatory authority; hence, together with the expired human medicines were not included in the cost analysis.

Cost estimations

The study used the median buyer prices from the International Drug Price Indicator Guide (IDPIG) as a primary source of medicines prices and when they were not available the Tanzanian Medical Stores Price Catalogue of 2015–2016 was used. In the absence of median buyer prices, the median supplier prices were used, with an inflation factor of 10% as recommended in the costing studies.11 Prices from the IDPIG were inflated further by 10% to account for local opportunity costs. Cost was calculated by multiplying the tallied quantities with unit prices for each item. In some cases, only the estimated value of the items in the local currency was reported without information about the identity and quantities, and this was common for cosmetics. In this case, the total value in the local currency was first converted to US$ by using relevant exchange rate for that year before adjusting to the present value using relevant consumer price indices.

Once the yearly value of falsified medicines, substandard medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients were estimated, we added other/operational costs which included the storage costs, transportation costs, cost of disposal and cost charges for court cases to arrive to the annual total cost. We measured the storage area (m2) which was multiplied by US$10/m2 which was the rate of rental charge used for warehouses by the Tanzania National Housing Corporation and reported by most distributors of pharmaceuticals. Yearly storage costs were obtained by multiplying monthly rental charges by 12. Storage costs for the importers and distributors were considered only for the year when there was an incident of confiscation of substandard or falsified medicine or cosmetics with banned ingredients.

Ethical considerations

The regulatory authority granted research permission and issued an official letter to all local importers and distributors requesting them to make the relevant data available to the researchers and assuring them that the data requested will be used for research purpose only. A consent form was provided to all the interviewees and signed prior to interviews.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not directly involved in the study. However, the research question and outcome measures were informed with concerns for safety and economic well-being of patients and the public. Poor-quality medicines and banned cosmetics not only contribute to increased morbidity and mortality but also can cause substantial economic loss to patients, families, health systems and everyone involved with the sale and manufacture of pharmaceuticals.

Results

Economic cost

The estimated economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients in Tanzania from 2005 to 2015 was US$16.20 million. Substandard medicines costed US$13.65 million, falsified medicines US$149 369 and cosmetics with banned ingredients US$1.29 million. Other costs that include transportation, storage, court cases and disposal costed US$1.09 million (table 1).

Table 1.

Costs of the products and other associated costs

| Year | Cost (US$) | |||||||

| Falsified | % | Substandard | % | Cosmetics | % | Other cost | Total cost | |

| 2005 | 33.3 | 37.1 | 56.5 | 62.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 89.8 |

| 2006 | 49.9 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 49.9 |

| 2007 | 63.8 | 0.0 | 19 424.4 | 8.3 | 162 478.8 | 69.5 | 51 720.9 | 233 688.0 |

| 2008 | 96.7 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 42 979.2 | 23.6 | 138 929.7 | 182 005.6 |

| 2009 | 1701.60 | 0.5 | 58 032.3 | 17.2 | 180 158.7 | 53.4 | 97 782.9 | 337 675.5 |

| 2010 | 17.6 | 0.0 | 57 299.5 | 25.1 | 52 983.1 | 23.2 | 117 907.7 | 228 207.9 |

| 2011 | 1676.4 | 0.3 | 398 474.0 | 63.5 | 123 347.6 | 19.7 | 103 913.3 | 627 411.3 |

| 2012 | 141 493.3 | 3.6 | 3 530 672.6 | 89.5 | 91 968.4 | 2.3 | 180 557.0 | 3 944 691.2 |

| 2013 | 2129.9 | 0.1 | 1 808 340.3 | 86.5 | 131 273.7 | 6.3 | 149 425.8 | 2 091 169.6 |

| 2014 | 1724.2 | 0.0 | 6 453 613.0 | 94.8 | 240 335.9 | 3.5 | 112 258.6 | 6 807 931.8 |

| 2015 | 382.7 | 0.0 | 1 326 139.4 | 76.8 | 265 326.6 | 15.4 | 134 143.4 | 1 725 992.1 |

| Total | 149 369.3 | 0.9 | 13 652 052.1 | 84.4 | 1 290 852.0 | 8.0 | 1 086 639.3 | 16 178 912.7 |

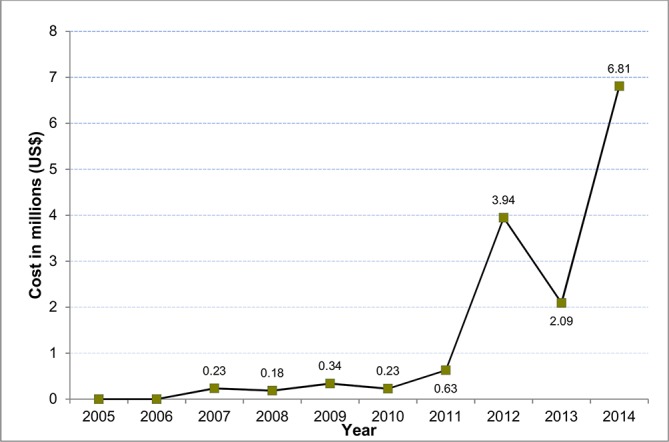

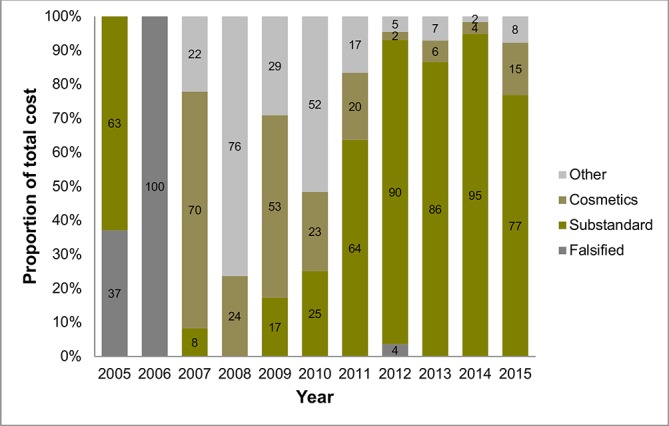

Between 2005 and 2011, the estimated annual economic cost increased from about US$90 to US$0.63 million, with some fluctuation in between. The annual cost increased sharply to US$3.94 million in 2012, then dropped to about US$2.09 million in 2014. The annual total cost rose again to US$6.8 million the following year (figure 1). From 2011, substandard medicines contributed two-thirds or more of the total cost. In 2006, only falsified medicines were recorded, and in 2007 and 2009 cosmetics contributed more than half of the total cost (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Estimated annual economic cost between 2005 and 2015.

Figure 2.

Relative contributions of the products to the total economic cost in Tanzania, 2005–2015.

Quantities

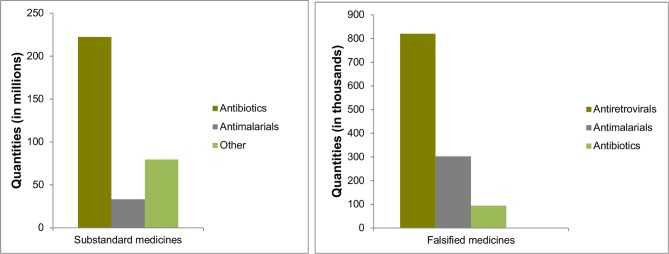

Between 2005 and 2015, there was a total of 519 889 388 and 1 216 630 substandard and falsified human medicines, respectively, that were recorded. Dosage forms were tablets/capsules, suspensions and injections (phials/ampoules). Among the group of substandard medicines, quantities of antibiotics were 222 236 052 (66%) which included 160 087 188 tablets/capsules; 61 957 667 bottles and 191 197 phials/ampoules (figure 3). Among the most commonly used antibiotics that have been identified are penicillin (83%), which included phenoxymethylpenicillin: 80 812 600 tablets and 65 bottles; amoxicillin: 495 677 capsules and 61 582 700 bottles; cloxacillin: 42 137 592 capsules and 2766 bottles; co-trimoxazole (sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim): 28 825 400 tablets and 110 bottles (13%); erythromycin 7 185 954 tablets (3%) and ciprofloxacin: 623 265 tablets and 372 000 bottles (0.4%).

Figure 3.

Quantities of poor-quality medicines in Tanzania, 2005–2015.

Among substandard medicines, quantities of antimalarials were 33 124 501 (10%) which included 33 032 825 tablets/capsules, 90 046 bottles and 1630 phials/ampoules (figure 3). Quantities of quinine were: 29 057 100 tablets, 24 bottles and 1630 ampoules which accounted for 88%; sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine: 3 392 103 tablets and 83 bottles (10%); amodiaquine: 268 543 tablets, 42 400 bottles; sulfamethoxypyrazine–pyrimethamine (SP): 216 450 tablets and 10 764 bottles; SP/artesunate: 87 990 tablets; artemether–lumefantrine: 8640 tablets and 36 775 bottles and chloroquine 2000 tablets. The group named ‘Other’ which accounted for 24% of substandard human medicines consists of many items including aminophylline 37 374 000 tablets and 2930 phials (47%), paracetamol 17 413 300 tablets and 50 905 bottles (22%), diazepam 9 141 500 tablets (11%) and prednisolone 7 101 000 tablets (9%).

For the group of falsified medicines, there were 819 660 tablets (67%) of antiretrovirals, followed by antimalarials and antibiotics, 302 609 (25%) and 94 200 (8%), respectively (figure 3). Other groups accounted for negligible percentage. All falsified antiretrovirals were a combination of stavudine, lamivudine and nevirapine tablets. Among falsified antimalarials, quantities of quinine tablets were 171 900 (57%), praziquantel–amodiaquine tablets 117 000 (39%), SP 11 704 tablets (4%), sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine tablets 1501 (0.5%) and artemether–lumefantrine 504 tablets (0.2%). Falsified antibiotics included doxycycline capsules 68 000 and cloxacillin capsules 26 200.

As for cosmetics, there were 250 000 kg, 833.20 kg, 646 cartons and 1476 items that were just recorded as ‘different types of cosmetics’.

Manufacturers of substandard and purported manufacturers of falsified medicines

Table 2 shows generic names of medicines and the anonymised names of manufactures of substandard medicines and purported manufacturers of falsified medicines which were repeatedly circulating in Tanzania between 2005 and 2015. Note that the letters used to denote manufacturers do not relate directly to their true names. Phenoxymethylpenicillin, ciprofloxacin, prednisolone, diazepam and salbutamol from manufacturer N were identified over several years implying consistent failure to meet Good Manufacturing Practice standards. The same was seen for manufacturer E, M and B for quinine, paracetamol and aminophylline, respectively.

Table 2.

Manufacturers of commonly identified poor-quality medicines

| Substandard medicines (manufacturers) | Year | |||||||

| 2005 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin | N | N | N | |||||

| Ciprofloxacin | N | N | ||||||

| Quinine | E | E | ||||||

| Prednisolone | N | N | N | N | ||||

| Paracetamol | M | M | ||||||

| Diazepam | N | N | N | N | ||||

| Aminophylline | B | B | ||||||

| Salbutamol | N | N | N | |||||

| Falsified medicines (purported manufacturers) |

Year | |||||||

| 2005 | 2008 | 2009 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| Quinine tablets | B | C | B, C, D | C, D, E | B, C | |||

| Sulfamethoxypyrazine–pyrimethamine | H | H, B | H, B | K | ||||

| Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine | E, I, J | E | C, J | |||||

| Halofantrine hydrochloride | A | A | ||||||

| Artemether–lumefantrine | F | F | ||||||

| Dihydroartemisinin–piperaquine | G | G | ||||||

Letter codes represent anonymised names of manufacturer or purported manufacturers.

The same observation was also made for falsified medicines, in that falsified products bearing the name of the same purported manufacturer were consistently found on the market over several years. For example, quinine and SP from manufacturer C and H, respectively, were identified circulating in the market for over 3 years.

Discussion

It is difficult to estimate the actual economic cost of substandard and falsified medicines in any country not least in a low-income setting because data are usually not available.12 However, using data from the regulatory authority, pharmaceutical importers and distributors, we were able to estimate this burden in Tanzania. Our findings show that the estimated economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients in Tanzania between 2005 and 2015 was US$16.20 million. Generally, the economic burden shows an increasing trend and the substandard medicines contribute the largest proportion of the total costs. The estimated economic cost represents 0.24% of the gross domestic product which is relatively large considering that Tanzania is one of the poorest countries in the world.

Based on the existing data, our analysis shows that there were large quantities of substandard and less falsified human medicines in Tanzania over the past 10 years. This include commonly used inexpensive antibiotics such as phenoxymethylpenicillin, amoxicillin, cloxacillin, erythromycin, sulfamethoxazole–trimethoprim; antimalarials such as quinine, sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine, sulfamethoxypyrazine–pyrimethamine and antiretrovirals among others. Use of poor-quality medicines is one of the main causes of antimicrobial resistance which was recently declared by WHO as a major global public health threat as it causes treatment to be difficult and more expensive.2 13 Several studies have reported high levels of antibiotic resistance in Tanzania, especially for commonly used and cheap antibiotics,14–17 which has prompted the government to develop a national action plan to curb antimicrobial resistance.18

Policy implications

The quantities and the economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines including cosmetics with banned ingredients in Tanzania over the past 10 years is alarming. Policy-makers in Tanzania need to continue to improve the existing post-marketing surveillance (PMS) and pharmacovigilance (PV) system for effective prevention, detection and response to poor-quality products, adverse effects and other medicines-related health and economic problems. Effective PMS and PV systems are essential components of any healthcare system. However, in low-income countries including Tanzania such systems are weak or non-existent, hence health problems associated with the use of substandard and falsified medicines such as adverse reactions, ineffective treatment or even death often go undetected.

The government and policy-makers need to provide more resources to the regulatory authorities in Tanzania to enhance supervision and inspection to ensure integrity of the supply chain of pharmaceuticals both in the public and the private sectors. Limited access to affordable essential medicines in the public health system has resulted in the opening of many private retail pharmacies and small accredited drug dispensing outlets in the country which have proven very difficult to control.19 As a consequence, malpractices are common including selling medicines without prescriptions, stocking medicines from unofficial sources, poor documentation and hiring of people without the required qualifications, making them the prime target for the business of substandard and falsified medicines.12

The fact that some substandard and falsified human medicines from certain manufacturers were confiscated over several years raise a more serious concern. This was observed, for example, for falsified quinine tablets purporting to be from manufacturer B and C, and SP tablets mimicking that of manufacturer H. There could be several reasons behind this; first, it could indicate a sign of insufficient inspection or ineffective removal of the product from the market; second, it could be that the products were easy to be falsified and smuggled into the country; third, poor compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices and lastly it could also imply that the culprits were not identified, or if identified the sanctions were not deterrent, hence continued to supply the products.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically combine data retrieved from the regulatory authority, importers and distributors of pharmaceuticals to estimate the economic cost of substandard and falsified medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients in a low-income country. The data also facilitated the identification of the manufactures of substandard medicines and manufacturers whose products were falsified which enabled us to isolate those whose products were repetitively found circulating in the market. However, this study has several limitations. First, we did not have morbidity and mortality data to facilitate the inclusion of patient and health system costs associated with the use of poor-quality medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients. This means our study underestimates the actual economic cost of these products. Second, some data were poorly recorded which made it difficult to follow the proper costing procedure of identification, quantification and valuation. Third, we were not able to determine the reasons behind the increasing quantities and costs. However, we believe this could be due to improvement in regulatory capacity and public awareness rather than an absolute increase in the amount of poor-quality medicines and banned cosmetics.

Conclusion

The economic cost of substandard and falsified human medicines and cosmetics with banned ingredients represent a relatively large loss of scarce resources for a low-income country like Tanzania. The increase in the quantities identified and the economic cost of these products over time could partly be due to improved regulatory capacity in terms of human resources, infrastructure, frequency of inspections, implementation of PMS, establishment of more zone offices and strengthened quality-control laboratory with WHO prequalification. These improvements in addition to efforts by the authority and the government to increase awareness among stakeholders could have positive and sustainable impact in the longer term. However, proliferation of retail drug outlets that are difficult to regulate and ineffective control of many porous borders will continue to be a challenge to the regulatory authority. Policy-makers should make the fight against substandard and falsified medicines a national priority agenda, including development of national strategies and action plans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the University of Bergen for providing open access publication fund to ATM. The authors also thank the Tanzanian Food and Drugs Authority and the involved importers and distributors of pharmaceuticals for their support in conducting the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: ATM and EAK conceived the idea of the study. ATM, EM and EAK designed the study. EM collected the data. ATM and EM analysed the data. ATM and EM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the research and publication committee of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no unpublished data for this study.

References

- 1. Faucon B, Murphy C, Whalen J. Africa’s Malaria Battle: Fake Drug Pipeline Undercuts Progress, in The Wallstreet Journal. 2013: London.. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887324474004578444942841728204 (Cited 13 June 2017).

- 2. WHO. A study on the public health and socioeconomic impact of substandard and falsified medical products. Geneva: World Health Organozation, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO. Counterfeit medicines. Revised Feb 2006. Fact sheet No. 275. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Renschler JP, Walters KM, Newton PN, et al. . Estimated under-five deaths associated with poor-quality antimalarials in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015;92(6 Suppl):119–26. 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clarke E. Counterfeit Medicines: The Pills That Kill in Telegraph. 2008 London. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/3354135/Counterfeit-medicines-the-pills-that-kill.html (Cited 13 June 2017).

- 6. Lipsitch M, Levin BR. The population dynamics of antimicrobial chemotherapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1997;41:363–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pisani E. Antimicrobial resistance: What does medicine quality have to do with it? Review on Antimicrobial Resistance 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8. United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute,. Counterfeit Medicines and Organized Crime. Turin, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caudron JM, Ford N, Henkens M, et al. . Substandard medicines in resource-poor settings: a problem that can no longer be ignored. Trop Med Int Health 2008;13:1062–72. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02106.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newton PN, Green MD, Fernández FM. Impact of poor-quality medicines in the ’developing' world. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2010;31:99–101. 10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Management Science for Health. Frye JE, International Drug Price Indicator Guide. Virginia: Center for Pharmaceutical Management, World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12. IOM (Institute of Medicine). Countering the Problem of Falsified and Substandard Drugs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. WHO. Antimicrobia Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Blomberg B. Antimicrobial resistance in bacterial infections in urban and rural Tanzania, in Institute of medicine Center for International health 2007, Bergen Norway. http://bora.uib.no/bitstream/handle/1956/2265/Main_Thesis_Blomberg.pdf.

- 15. Moremi N, Claus H, Mshana SE. Antimicrobial resistance pattern: a report of microbiological cultures at a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16:756 10.1186/s12879-016-2082-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blomberg B. Fake medicines, a threat to human health (letter). Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: The Guardian, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Blomberg B, Mwakagile DS, Urassa WK, et al. . Surveillance of antimicrobial resistance at a tertiary hospital in Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2004;4:45 10.1186/1471-2458-4-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. The United Republic of Tanzania. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in Tanzania: Time for bold actions. Dar es Salaam: The United Republic of Tanzania, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mori AT, Kaale EA, Risha P. Reforms: a quest for efficiency or an opportunity for vested interests'? A case study of pharmaceutical policy reforms in Tanzania. BMC Public Health 2013;13:651 10.1186/1471-2458-13-651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO. Seventieth World Health Assembly. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.