Abstract

We describe a case report of a 53-year-old man with a 5-months history of progressive jaundice and upper abdominal pain. The patient was further evaluated and finally diagnosed with a high-grade ampullary neuroendocrine tumour (based on endoscopic-guided biopsy). Thereafter, he underwent pancreatoduodenectomy and adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. This extremely rare case presents his long-lasting disease-free survival compared with similar cases; this case report exemplifies a new, potentially efficient method for treating high-grade papillary neuroendocrine tumour and may pave the way for further clinical trials utilising this blueprint in the treatment of related conditions.

Keywords: small intestine cancer, chemotherapy

Background

Neuroendocrine tumour (NET) of the ampulla of Vater is an uncommon form of NET whose rarity has left physicians with a small body of case reports and limited single-institution case series to rely on.

Indeed, ampullary NET constitutes a mere 1% of all gastrointestinal NET cases.1 Regarding the natural history of NET with the ampullary origin, what is evident is that its behaviour is more aggressive than its duodenal counterpart and it tends to metastasize readily.2

As mentioned, there is lack of confident data to guide the proper management of ampullary NET. Currently, the bulk of available data is based on small retrospective studies that recommend approaching a similar treatment to its lung counterpart (ie, small cell lung cancer).3

One of the modalities that is employed for localised ampullary management is surgery. But the extent of resection (ie, pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) or local resection) remains an open question.4 Nevertheless, surgery alone is rarely curative for localised diseases, so a multimodality approach is needed for most patients.3

Generally, the prognosis of high-grade ampullary NET is poor, with a median survival of 38 months for localised disease.5

Herein, we report a case of localised ampullary NET with disease-free survival of 89 months following surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy.

Case presentation

A 53-year-old man complaining of anorexia, moderate jaundice and right upper abdominal pain for 5 months was admitted to Shohada-e-Tajrish General Hospital in June 2010. Results of laboratory tests were consistent with direct hyperbilirubinaemia and slightly increased pancreatic enzymes. Thereafter, his condition was evaluated with contrast-enhanced abdominal CT that detected a slightly dilated common biliary duct (17 mm) and pancreatic duct. These findings made the patient candidate for endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) that an ill-defined hypoechoic mass (2.5×2.3 cm) was detected at the ampulla of Vater. The patient also underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), while endoscopic snare papillectomy and endobilliary stenting were also performed. Biopsy of the lesion depicted a high-grade NET. The absence of visceral metastasis and peripancreatic lymphadenopathy was confirmed by whole-body CT scan and EUS. PD (the Whipple procedure) was performed and pathological examination of the specimen delineated a 3.0×2.5×1.5 cm tumorous mass that was consistent with ‘poorly differentiated carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation’ (figure 1), with negative surgical margins and mitotic index of 14 mitoses in 10 high-power fields (HPF) (figure 2). The related immunohistochemistry study was positive for chromogranin and synaptophysin, while negative for neuron-specific enolase. Ki67 is positive in more than 20% of tumorous cells (figure 3).

Figure 1.

Microscopy shows duodenal wall is involved by a relatively well defined neoplasm. No tumorous invasion to the pancreas is seen (H&E stain) ×200.

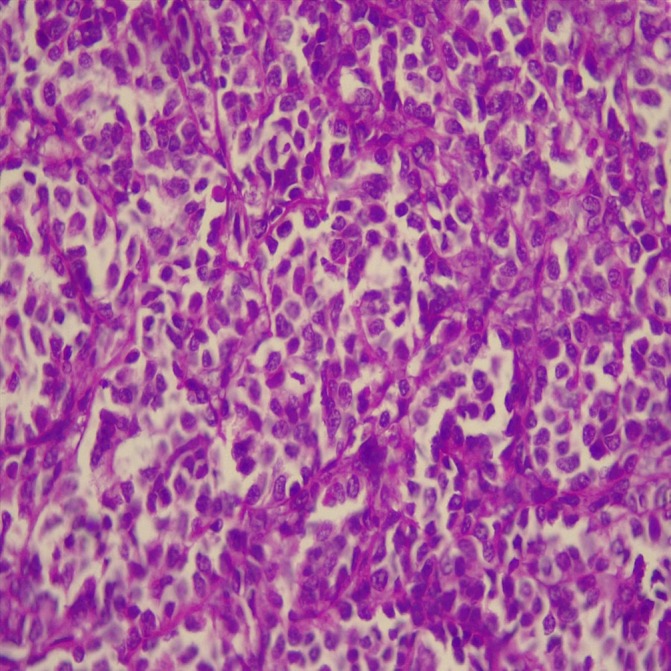

Figure 2.

The tumour is composed of sheets of mildly pleomorphic cells with high mitotic count. The mitotic count is 14/10 high power field (H&E stain) ×400.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemistry for Ki67 is positive in more than 20% of tumorous cells (A). Staining for chromogranin (B) and synaptophysin (C) is positive in the tumour cells ×400.

The pathological examination also revealed five reactive lymph nodes. Postoperative octreotide scan revealed no increased uptake. Accordingly, the clinical stage assigned as T2N0M0, based on American Joint Committee on Cancer 2010. Thereafter, the patient received a combination chemotherapy using cisplatin 25 mg/m² and etoposide 100 mg/m² every 3 weeks for six cycles.

Outcome and follow-up

He continued to be evaluated at the radiotherapy-oncology clinic over the next 89 months to the present time. He is currently asymptomatic and he displays no signs to suggest tumour relapse in routine abdominal/pelvic multiphasic CT scans.

Discussion

Notwithstanding that NET was initially described by Siegfried Oberndorfer more than a century ago, there are some ambiguities regarding the best way to manage some of its subgroups (including ampullary subtype).6 This issue may be attributed to its extreme rarity. Less than 140 patients diagnosed with ampullary NET have been reported by 2012, mostly in the form of case reports. Likewise, it accounts for less than 0.05% of all NETs. The incidence increases with age and peaks between the ages of 50 and 60. There is female to male predominance with a ratio of 3:1.7

The most common related symptoms include jaundice (60%) and upper abdominal pain (40%), although weight loss and upper gastrointestinal bleeding can also occur.8

In addition to history taking and physical examination, there are some modalities that can help physicians detect the causes of the aforementioned symptoms, which include abdominal CT scan, ERCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) and EUS. Since abdominal CT scan usually cannot identify the small primary tumour that is located at the ampulla of Vater, additional modalities (ie, ERCP, MRCP or EUS) are needed.

The list of related differential diagnosis is so diverse. The most frequent ones are duodenal adenoma/adenocarcinoma gastrointestinal stromal tumour. Histopathological examination is essential for further management.

Because ampullary NETs and their metastases often express somatostatin receptors, octreotide scan (a somatostatin analogue) can be used to detect them with a sensitivity of 86%.2 When the diagnosis was confirmed (ie, through histopathology assessment), the physician can order an octreotide scan to discover possible regional or distant involvement.

The classification and titles of NETs have been changed during the last years. According to European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society and WHO (ENETS/WHO) classification, there are two main subgroups of NET: well-differentiated (that further subdivided into low and intermediate grade) and poorly differentiated (also named high grade). This recent classification is based on proliferative rate which can be assessed using either mitotic count in 10 HPF or Ki-67 index. The mitotic cut-off to define high-grade (G3) NET is 20 in 10 HPF. In addition, the Ki-67 index cut-off value for G3 NET is >20%.9

Currently, there is lack of data regarding the best way to manage ampullary NET. Consequently, the available approach to ampullary NET treatment is based on case reports and retrospective unicenteric studies. As a result, surgical excision is seen as an important part of ampullary NET management despite the fact that its extent remains an open question (ie, ranging from local resection to PD with lymphadenectomy). PD has the potential of better locoregional control, however, at the expense of more adverse effects. Local resection is a reasonable alternative to the radical procedure to decrease the surgical morbidity and preserve organ function, while carrying the risk of incomplete removal of the tumour. High-grade ampullary NET have a poor prognosis with a propensity to rapid dissemination, even in the case of the local disease. Therefore, surgical excision of the tumour is not sufficient and treatment should be followed by adjuvant systemic therapy. Generally, high-grade ampullary NETs are treated with platinum-based chemotherapy, according to small cell carcinoma guideline.10

The prognostic significance of either tumour, node and metastases (TNM) staging or tumour grade is shown in several studies.11 12 The prognosis of high-grade NET is generally poor for all TNM stages, with a median survival of 38 months for localised disease, 16 months for regional disease and 5 months for metastatic disease.5 13 14 However, our patient with high-grade ampullary NET has been disease free for approximately 89 months after receiving PD and adjuvant chemotherapy for six cycles of cisplatin plus etoposide.

This case report with its totally robust results has the potential to be a worthwhile clue in the management of patients suffering from high-grade papillary NET. Further studies are needed to confirm these results.

Learning points.

Neuroendocrine tumour involving ampulla of Vater is extremely rare disease, so its ideal management remains a major dilemma.

Currently, the available data are based on limited retrospective studies that propose surgical excision and postoperative chemotherapy.

The extent of resection and the ideal chemotherapy regimen remain ambiguous.

Treatment protocol in the form of pancreatoduodenectomy and adjuvant cisplatin plus etoposide has the potential to introduce an efficient treatment protocol for clinical trials in the related conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alistair Faghani, Managol Safavi, MD, Masoumeh Hosseini and Masoumeh Shaeban Bolookat for their kind contribution to this paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: FT-H provided the data and writing the letter. AM provided the pathology data. MM edited the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer 2003;97:934–59. 10.1002/cncr.11105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter JT, Grenert JP, Rubenstein L, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the ampulla of Vater: biological behavior and surgical management. Arch Surg 2009;144:527–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sorbye H, Strosberg J, Baudin E, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma. Cancer 2014;120:2814–23. 10.1002/cncr.28721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartel M, Wente MN, Sido B, et al. Carcinoid of the ampulla of Vater. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;20:676–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bethesda MD. Previous version: SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oberg K. Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs): historical overview and epidemiology. Tumori 2010;96:797–801. 10.1177/030089161009600530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albores-Saavedra J, Hart A, Chablé-Montero F, et al. Carcinoids and high-grade neuroendocrine carcinomas of the ampulla of vater : a comparative analysis of 139 cases from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program– a population based study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2010;134:1692–6. 10.1043/2009-0697-OAR.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayant M, Punia R, Kaushik R, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the ampulla of vater: presentation, pathology and prognosis. JOP 2012;13:263–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rindi G, Arnold R, Bosman FT, et al. Nomenclature and classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms of the digestive system. WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ku GY, Minsky BD, Rusch VW, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal junction: review of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering experience. Ann Oncol 2008;19:533–7. 10.1093/annonc/mdm476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jann H, Roll S, Couvelard A, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of midgut and hindgut origin: tumor-node-metastasis classification determines clinical outcome. Cancer 2011;117:3332–41. 10.1002/cncr.25855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Rosa S, Inzani F, Vanoli A, et al. Histologic characterization and improved prognostic evaluation of 209 gastric neuroendocrine neoplasms. Hum Pathol 2011;42:1373–84. 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3063–72. 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2010. 2013: National Cancer Institute:9. [Google Scholar]