Abstract

Objectives

Limited studies have identified predictors of early and late hospital readmissions in Australian healthcare settings. Some of these predictors may be modifiable through targeted interventions. A recent study has identified malnutrition as a predictor of readmissions in older patients but this has not been verified in a larger population. This study investigated what predictors are associated with early and late readmissions and determined whether nutrition status during index hospitalisation can be used as a modifiable predictor of unplanned hospital readmissions.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Two tertiary-level hospitals in Australia.

Participants

All medical admissions ≥18 years over a period of 1 year.

Outcomes

Primary objective was to determine predictors of early (0–7 days) and late (8–180 days) readmissions. Secondary objective was to determine whether nutrition status as determined by malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST) can be used to predict readmissions.

Results

There were 11 750 (44.8%) readmissions within 6 months, with 2897 (11%) early and 8853 (33.8%) late readmissions. MUST was completed in 16.2% patients and prevalence of malnutrition during index admission was 31%. Malnourished patients had a higher risk of both early (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.73) and late readmissions (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.06 to 128). Weekend discharges were less likely to be associated with both early (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.91) and late readmissions (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.97). Indigenous Australians had a higher risk of early readmissions while those living alone had a higher risk of late readmissions. Patients ≥80 years had a lower risk of early readmissions while admission to intensive care unit was associated with a lower risk of late readmissions.

Conclusions

Malnutrition is a strong predictor of unplanned readmissions while weekend discharges are less likely to be associated with readmissions. Targeted nutrition intervention may prevent unplanned hospital readmissions.

Trial registration

ANZCTRN 12617001362381; Results.

Keywords: quality in health care, internal medicine, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A large multicentre study involving 19 924 patients with 26 253 admissions.

Readmissions to all other hospitals were captured.

Used cumulative incidence function for unbiased estimation of readmissions over time.

This study did not take into account psychiatric factors and discharge medications.

Functional status of the patients at discharge was not determined.

Introduction

Recent advances in medicine have led to a vast improvement in life expectancy but with increasing numbers of patients with multiple clinical problems. Although the length of hospital stay has improved and there has been a decline in the number of beds for acute patients, unplanned hospital readmissions have increased.1 Hospital readmissions strain the already busy healthcare settings and not only increase the healthcare costs but also expose patients to hospitalisation-associated complications.2 Medicare data in the USA suggests that 20% of patients return to hospital within 30 days of discharge, of which 90% are unplanned admissions with the estimated cost to the extent of US$30 billion.3 Given a considerable financial burden for hospitals and adverse outcomes for patients, hospital readmissions are increasingly used as quality indicators for institution’s performance benchmark with a risk of reduced reimbursements for poorly performing hospitals.4

Although numerous readmission prediction tools are available, still preventing readmissions has been problematic, as the discriminative power of the available prediction tools has been modest.5 Zhou et al has highlighted the need for rigorous validation of the existing risk-predictive models for potentially avoidable hospital readmissions, as the performance of the existing models is inconsistent.6 They have suggested that most of the models were developed based on healthcare data from the USA, which might not be applicable to patients from other settings. Furthermore, different factors may influence readmissions over different periods following hospital discharge.7 Studies have identified that some of the factors responsible for readmissions, for example, medication errors, may be potentially modifiable and there may be similar other factors which are yet to be identified and could be the target for future interventions.8

Very few studies have determined predictors of unplanned readmissions at different periods following hospital discharge in the Australian healthcare settings. Moreover, the available studies have not captured readmissions to all other hospitals following discharge.9 10 Malnutrition is associated with adverse health outcomes for patients and leads to increased healthcare costs.11 12 A recent study has suggested that malnutrition is a strong predictor of hospital readmissions and mortality but this study included only a small sample of older general medical patients in a single hospital setting.13 Whether nutrition risk can be used as a predictor of readmissions in a broad range of medical patients needs further confirmation. This study was designed to determine predictors of hospital readmissions in early and late periods following hospital discharge across all medical specialties, in two major teaching hospitals in Australia and captured readmissions to all other hospitals. The other aim was to determine whether admission nutrition status, as determined by the malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST), can be used to predict hospital readmissions.

Methods

Setting and study population

This is a retrospective study and data were collected from two large urban teaching hospitals in South Australia. Ethical approval was granted on 4 August 2017 and this study was registered with Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTRN 12617001362381). This study included all live medical admissions in Flinders Medical Centre (FMC) and Royal Adelaide Hospital (RAH) from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2016. For this study, a readmission was only counted once as a readmission, relative to the prior index admission. All subsequent admissions then re-entered the cohort as a new index admission. All elective readmissions were excluded from the data set.

Data sources

In this study, we derived our cohort and variables of interest using the hospital’s central computer database. All the data in the two involved health facilities are prospectively collected as part of regular hospital operations.

Objectives

The primary objective for this study was to determine predictors for early readmissions, defined as readmissions within 7 days post discharge from index hospitalisation while late readmissions were defined as readmissions within 8–180 days post discharge. The secondary objective was to determine whether nutrition status as determined by MUST can predict readmissions and can be used as a modifiable risk factor. Only non-elective admissions were included in this study.

Analysis

Variables of interest

Patients were categorised into three groups based on the pattern of readmission: not readmitted within 180 days (base category), readmitted within 7 days of index admissions (early readmissions) and readmitted within 8 to 180 days after index admission (late readmissions). Patients not readmitted within 180 days were defined as the reference group for subsequent comparisons.

Previous studies have suggested that different variables may be responsible for various stages of readmissions.14 15 Variables relating to the index admission that may be associated with early readmissions include clinical instability as determined by intensive unit care (ICU) admissions, number of medical emergency response team (MET) calls, complications during admission and length of hospital stay (LOS).14 16 Late readmissions may be associated with markers of chronic illness burden as reflected by the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), social determinants of health including marital status, whether patient was living alone or with family and the socioeconomic status as determined by the composite Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (IRSD).17 18 IRSD relates to the degree of area-based social disadvantage based on low levels of income and education and high levels of unemployment and is provided nationally by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.19 Nutrition status of the participants during index admission was determined by the use of MUST.20 It is a requirement that all patients admitted in the RAH and FMC are screened for malnutrition at admission using MUST. MUST includes a body mass index score, a weight loss score and an acute disease score and a total MUST score of 0 indicates low risk, 1 medium risk and ≥2 high risk of malnutrition.21 For this study, patients with a MUST score of 0 were classified as nourished and those with a score ≥1 were classified as malnourished.

Statistical analysis

Data were assessed for normality using skewness and kurtosis test. Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) while categorical variables as median (IQR). We used multinomial polytomous logistic regression to model the association between variables of interest and early and late readmissions (with no readmissions within 180 days as the reference). LOS was adjusted for in-hospital mortality. The model was adjusted for following covariates—age, gender and CCI and LOS.

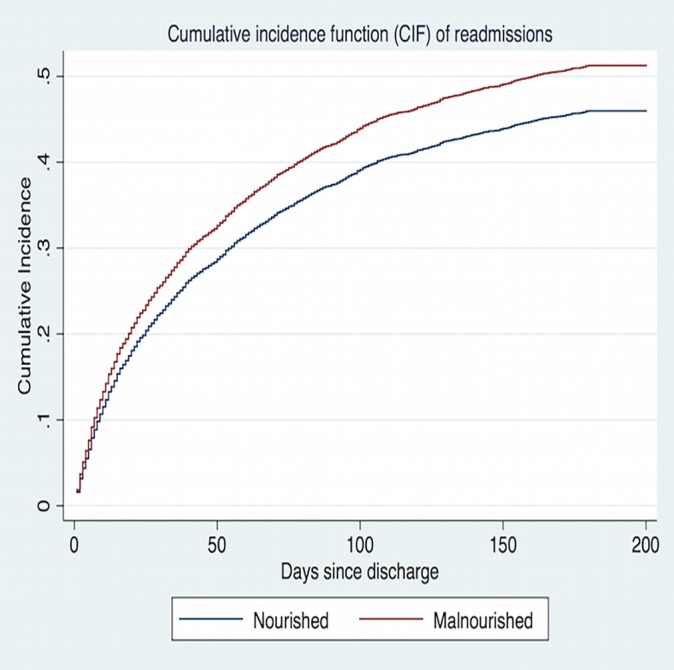

As death is a competing risk for readmissions, the interpretation of the Kaplan-Meier survival curve may not be realistic in clinical practice and may overestimate the incidence of readmissions over time.22 Therefore, we used cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) for unbiased estimation of the probability of readmissions over time according to the nutrition status of the patients determined during the index hospitalisation.23 24 The cumulative risk regression model as suggested by Fine and Grey25 determined the subdistribution HR (SHR) and a CIF curve for readmissions was plotted. The model was adjusted for the following covariates: age, gender, CCI and LOS.

All data analyses were performed using STATA V.15 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) and a p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement as this study involved only retrospective data collection.

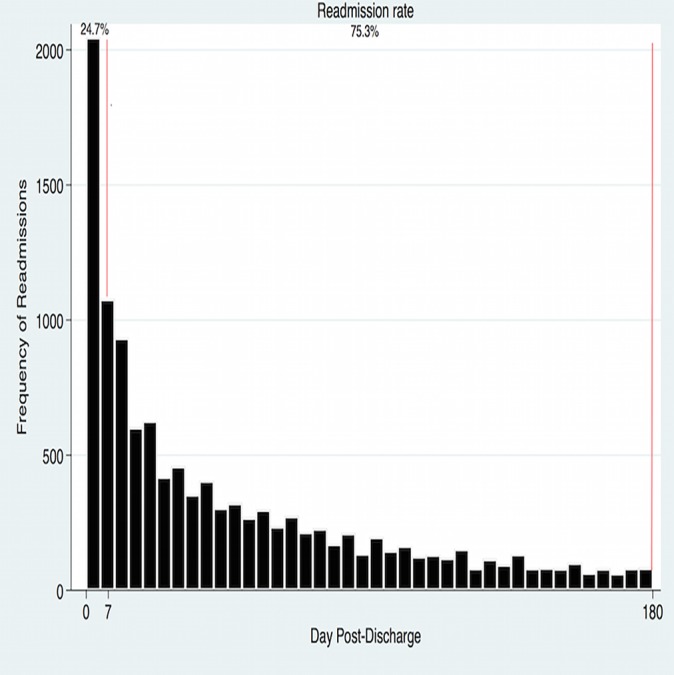

Results

There were a total of 26 253 admissions, representing 19 924 patients, between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2016, with 52.3% men. The overall readmission rate at 6 months was 44.8%. A total of 2897 (11.0% of index admissions) patients were readmitted within 7 days of discharge (early readmissions) whereas 8853 (33.8% of index admissions) were readmitted within 8–180 days of discharge (late readmissions) (table 1). The distribution of readmissions by post discharge day is shown in figure 1, with 24.7% of readmissions occurring in the early period, and 75.3% occurring late after hospital discharge. MUST was completed in 4251 (16.2%) of patients during index admission and prevalence of malnutrition according to the MUST was 31%. Patients who underwent MUST screening were significantly older (67.8 years (SD 18.4) vs 66.0 years (SD 18.7), p<0.001), had a higher CCI (1.8 (SD 2.3) vs 1.7 (SD 2.2), p<0.005) and a longer LOS (5.7 days (IQR 8.7) vs 3.1 days (IQR 4.5), p<0.001) but were less likely to be of indigenous status (84 (1.8%) vs. 670 (2.8%), p<0.001) than those who missed MUST screening. Majority of patients (80.5%) were discharged over the weekdays and only 19.5% discharges occurred over the weekends.

Table 1.

Initial hospitalisation and patient characteristics by readmission status

| Variable | Early readmissions (0–7 days) (n=2897, 11.0%) |

Late readmissions (8–180 days) (n=8853, 33.8%) |

No readmission (within 180 days) (n=14 503, 55.2%) |

| Age n (%) | |||

| <40 | 305 (10.5) | 863 (9.8) | 1616 (11.1) |

| 41–59 | 664 (22.9) | 1869 (21.1) | 3156 (21.8) |

| 60–79 | 1189 (41.0) | 3525 (39.8) | 5343 (36.8) |

| >80 | 739 (25.5) | 2596 (29.3) | 4388 (30.3) |

| Sex Male n (%) | 1588 (54.8) | 4688 (53.0) | 7528 (52.0) |

| Confirmed indigenous status n (%) |

169 (5.8) | 249 (2.8) | 329 (2.3) |

| Marital status n (%) | |||

| Single | 96 (7.9) | 398 (9.2) | 496 (7.3) |

| Married/partnered | 532 (43.7) | 1957 (45.2) | 2962 (43.4) |

| Divorced/separated | 138 (11.4) | 513 (11.8) | 496 (7.3) |

| Home alone n (%) | 387 (31.9) | 1369 (31.6) | 1957 (28.6) |

| LOS median (IQR) | 4.0 (6.1) | 3.7 (5.0) | 2.8 (4.0) |

| ICU hours mean (SD) | 5.9 (37.2) | 3.3 (22.1) | 3.5 (33.4) |

| MET call during admission n (%) | 91 (7.5) | 274 (6.3) | 475 (6.9) |

| Complications during admission n (%) | 707 (24.4) | 1745 (19.7) | 2725 (18.8) |

| Previous healthcare use median (IQR) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 0 (1.0) |

| Malnourished n (%) | 172 (37.6) | 514 (33.2) | 632 (28.1) |

| MUST score* mean (SD) | 0.38 (0.48) | 0.33 (0.47) | 0.27 (0.44) |

| MUST group† n (%) | |||

| Low risk | 286 (62.4) | 1033 (66.8) | 1614 (71.9) |

| Medium risk | 65 (14.2) | 205 (13.2) | 252 (11.2) |

| High risk | 107 (23.4) | 309 (20.0) | 380 (16.9) |

| BMI mean (SD) | 26.5 (7.3) | 26.6 (7.6) | 27.0 (7.4) |

| Weekend discharge | 487 (16.8) | 1645 (18.6) | 2578 (19.5) |

| Discharge time n (%) | |||

| 0600–1200 | 817 (28.2) | 2453 (27.7) | 4031 (27.8) |

| 1201–1800 | 1854 (64.0) | 5811 (65.6) | 8843 (61.0) |

| 1801–0559 | 226 (7.8) | 589 (6.7) | 1629 (11.2) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index mean (SD) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.3) | 1.4 (2.0) |

| IRSD‡ score mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.8) | 5.3 (2.7) | 5.4 (2.9) |

*Higher MUST score indicates worse nutrition status.

†MUST group, low risk=MUST score 0, medium risk=MUST score 1, high risk=MUST score ≥2.

‡Higher IRSD score indicates better socioeconomic status.

BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; IRSD, Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage; LOS, length of hospital stay; MET, medical emergency response team; MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool.

Figure 1.

Distribution of readmissions.

Predictors of early and late readmissions

After adjusted analyses, this study found that higher Charlson Comorbidity Index, the number of admissions in the prior 6 months, LOS of index admission and MET calls were associated with higher risk of both early and later readmissions. Similarly, patients who were single, divorced or separated and socially disadvantaged had higher odds of a readmission in both periods (table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable model for early and late readmissions

| Variable | Early readmissions (0–7 days) OR (95% CI)* |

Late readmissions (8–180 days) OR (95% CI) |

| Age | ||

| ≤40 (reference) | – | – |

| 41–59 | 0.90 (0.77 to 1.05) | 0.98 (0.89 to 1.09) |

| 60–79 | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.07) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) |

| ≥80 | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.94) | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.70) |

| Male gender | 1.07 (0.99 to 1.16) | 1.02 (0.96 to 1.08) |

| Indigenous status | ||

| Non-indigenous (reference) | – | – |

| Indigenous | 2.00 (1.64 to 2.45) | 1.06 (0.89 to 1.26) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married (reference) | – | – |

| Single | 1.34 (1.04 to 1.73) | 1.40 (1.19 to 1.63) |

| Divorced/separated | 1.50 (1.20 to 1.86) | 1.54 (1.33 to 1.78) |

| Home status | ||

| Lives with family (reference) | – | – |

| Lives alone | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.33) | 1.20 (1.08 to 1.33) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 1.27 (1.24 to 1.29) | 1.18 (1.16 to 1.20) |

| Length of stay (index admission, in days) | 1.02 (1.02 to 1.03) | 1.01 (1.01 to 1.02) |

| Admissions in the last 6 months (per admission) | 3.20 (2.95 to 3.50) | 2.93 (2.77 to 3.10) |

| Socioeconomic status† | ||

| Least disadvantaged (reference) | – | – |

| Most disadvantaged | 1.40 (1.22 to 1.60) | 1.20 (1.10 to 1.31) |

| Day of discharge | ||

| Weekday (reference) | – | – |

| Weekend | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.91) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.97) |

| Time of discharge | ||

| AM (0600–1159) | 0.99 (0.90 to 1.09) | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.02) |

| Reference (1200–1759) | – | – |

| PM (1801–0559) | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.25) | 0.87 (0.76 to 1.00) |

| ICU stay during admission | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.07) | 0.70 (0.59 to 0.84) |

| MET calls during admission | 1.30 (1.01 to 1.70) | 1.27 (1.01 to 1.17) |

| Complications during admission | 1.29 (1.16 to 1.43) | 1.09 (1.11 to 1.34) |

| BMI during index admission | 0.99 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0.98 (0.97 to 1.01) |

| MUST class | ||

| Nourished (reference) | – | – |

| Malnourished | 1.39 (1.12 to 1.73) | 1.23 (1.06 to 1.42) |

*OR were derived using a multinomial logistic regression, using readmission category none (within 180 days), early (within 7 days) and late (8–180 days) readmissions as the outcome variable.

†Socioeconomic status was determined by Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage (IRSD).

BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; MET, medical emergency response team; MUST, malnutrition universal screening tool.

Patients who were malnourished had a 39% higher risk of early readmission (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.73) and this risk remained elevated at 23% in later period following discharge (OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.42). The adjusted SHR for readmissions with mortality as a competing risk was 1.17 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.28) and the CIF curve is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence estimate model for readmissions with death as a competing risk. Competing risk regression was used to estimate subdistribution HR (SHR), 1.17 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.28). Model adjusted for covariates—age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index and length of hospital stay.

Patients who were discharged over the weekends had a lower odds of being admitted in both early (0.81, 95% 0.74–0.91) and late periods (0.91, 95% 0.84–0.97) following discharge compared with those discharged over the weekdays (table 2). Patients who were discharged over the weekend were found to have a shorter LOS (median 2.3 (IQR 1.2–4.1) vs 3.6 (IQR 1.8–6.8, p<0.001), fewer nosocomial complications (12.9% vs 19.3%, p<0.001), were less likely to be admitted in the ICU (3.3% vs 4.9%, p<0.001) during index hospitalisation and were more likely to be discharged home rather than a residential facility (96.1% vs 91.2%, p<0.001) as compared with those discharged over the weekdays.

Predictors of early readmissions

Indigenous patients were more likely to be readmitted early after hospital discharge (OR 2.00, 95% CI 1.64 to 2.45) but early readmissions were less likely among patients who were ≥80 years of age (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.94) (table 2).

Predictors of late readmissions

Late readmissions occurred more likely among patients who were living alone at home (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.33) but were less often if patient had been admitted to the ICU during index admission (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.84) (table 2).

Discussion

The results of the present study highlight predictors of readmissions in early and late periods following hospital discharge in the Australian healthcare settings. In line with the previous studies,3 5 16 we found that higher number of comorbidities, LOS and higher complications during hospital admission were associated with a higher readmission risk. A significant finding of this study is that nutrition status during index admission predicts both early and late readmissions. Patients who were malnourished during index hospitalisation had a 39% higher risk of being readmitted early after hospital discharge and this risk remains significantly increased even in the later periods following hospital discharge. Our study validates the findings of a previous study13 that impaired nutrition status during index hospitalisation increases the risk of readmissions among medical patients across all specialties. The prevalence of malnutrition in our study was 31%, which is comparable to other studies among hospitalised patients.26 The concerning finding is that only 16% of the patients underwent nutrition screening during hospital admission, which highlights that a significant proportion of malnourished patients are missed. Studies indicate that early nutrition intervention may have a beneficial effect in improving nutritional and clinical outcomes among malnourished patients.27 28 Stratton et al in their meta-analysis involving 1190 patients found that readmissions rate was significantly reduced in patients who received oral nutrition supplements (33.8% vs 23.9%, p<0.001).28 However, the studies involved in this meta-analysis included only older patients, and whether nutrition supplementation can reduce readmissions in younger patients is still unknown. There is a window of opportunity to target malnutrition among hospitalised patients and future intervention studies should target patients of all age groups to see if it helps reduce readmissions.

We also found that patients who were discharged on weekends had lower readmission rates (both in early and late periods following discharge) as compared with those discharged over the weekdays. One explanation could be that patients who were considered at a high risk for readmission may already have been selected for weekday discharge. In addition, this study found that patients discharged on a weekend had a shorter length of hospital stay, suffered fewer complications during admission and were more likely to be discharged home, suggesting that these patients may have been less medically complicated. These findings suggest that hospitals need not worry that weekend discharges will adversely affect their readmission statistics; however, the results need to be interpreted with caution as patients discharged on weekends were healthier and less likely to be malnourished. It is also possible that these patients had fewer post-hospital needs than those discharged over the weekdays. Our study results are in line with a similar study conducted by Cloyd et al who found lower 30-day readmission rates in patients discharged over the weekends but this study included only surgical patients.29

We found that indigenous status is a strong predictor of early readmissions but not late readmissions among Australian hospitalised patients. Indigenous Australians are socially isolated and are among the most disadvantaged groups in Australia.30 There is a very high incidence of self-discharge or discharge against medical advice among indigenous Australians and it is possible that non-resolution of acute illness may be a contributing factor for early readmissions in this group.31 We also found that readmissions were less frequent among very old people. LOS among patients older than 80 years was significantly longer in our patients (which could indicate delayed discharge) and they were more likely to be discharged to a nursing home (NH) rather home, which could be the reason for their less frequent presentation early after hospital discharge.

With regards to late readmissions, we found that patients living alone are more likely to be readmitted than those living with family. This finding is in line with previous studies,32 33 but unlike other studies,14 34 we found that patients who had an ICU admission are less likely to have late readmissions. As ICU admission is a marker of clinical instability,35 it is more likely to be associated with an early rather than late readmission. It is also possible that these patients had a higher mortality after hospital discharge, which could have been a competing risk for readmissions, and thus had fewer late readmissions.

In conclusion, multiple factors including admission nutrition status predict rehospitalisation. Moreover, this study adds significant evidence that weekend discharges are not associated with an increased risk of readmissions in medical patients.

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of the data analysed. Our preference to compare readmissions within the first week to admissions within 8–180 days following discharge were based on clinical judgement and analysis using an alternate time period (ie, 14 days vs 30 days vs 90 days) might reveal different results. This study did not consider other important factors such as functional status and psychiatric illnesses, which can have a significant impact on unplanned readmissions. We did not have information about the discharge medications, which have been shown to be of critical importance and may lead to adverse events after discharge.8 Lastly, although this was a large sample, data from only two hospitals were included, which could limit generalisability. Strengths include large sample size and inclusion of all readmissions to all hospitals in the state.

Conclusion

Among patients discharged from hospital, malnutrition as determined by MUST is a risk factor for both early and late readmissions. There is some indication that early readmissions may have different causal pathways than late readmissions with weekend discharges associated with a significantly lower risk of readmissions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YS and CT designed and led the study. YS, CT, PH and CH carried out the analysis and interpretation. CH was responsible for data acquisition. YS, PH and CH provided statistical input. YS wrote the manuscript, which was critically reviewed by CT. CT, BK, RS and MM edited the manuscript. All authors approved final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Flinders Centre for Clinical Change and Health Care Research (FCCCHCR) collaboration grant from Flinders University, South Australia (grant number: 36373)

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee (SAC HREC) no. 216.17

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and only after permission by the Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee (SAC HREC).

References

- 1. Royal College of Physicians. Hospitals on the Edge? The Time for Action. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2012. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/guidelines-policy/hospitals-edge-time-action. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med 2009;360:1418–28. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Donzé J, Lipsitz S, Bates DW, et al. Causes and patterns of readmissions in patients with common comorbidities: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2013;347:f7171 10.1136/bmj.f7171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bhalla R, Kalkut G. Could Medicare readmission policy exacerbate health care system inequity? Ann Intern Med 2010;152:114–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, et al. Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA 2011;306:1688–98. 10.1001/jama.2011.1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhou H, Della PR, Roberts P, et al. Utility of models to predict 28-day or 30-day unplanned hospital readmissions: an updated systematic review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011060 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Graham KL, Wilker EH, Howell MD, et al. Differences between early and late readmissions among patients: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:741–9. 10.7326/M14-2159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:161–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Scott IA, Shohag H, Ahmed M. Quality of care factors associated with unplanned readmissions of older medical patients: a case-control study. Intern Med J 2014;44:161–70. 10.1111/imj.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li JY, Yong TY, Hakendorf P, et al. Identifying risk factors and patterns for unplanned readmission to a general medical service. Aust Health Rev 2015;39:56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lim SL, Ong KC, Chan YH, et al. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin Nutr 2012;31:345–50. 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC, et al. identification and impact on patients and the heathcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:514–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sharma Y, Miller M, Kaambwa B, et al. Malnutrition and its association with readmission and death within 7 days and 8-180 days postdischarge in older patients: a prospective observational study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018443 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Graham KL, Marcantonio ER. Differences Between Early and Late Readmissions Among Patients. Ann Intern Med 2015;163:650 10.7326/L15-5149-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fudim M, O’Connor CM, Dunning A, et al. Aetiology, timing and clinical predictors of early vs. late readmission following index hospitalization for acute heart failure: insights from ASCEND-HF. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20 10.1002/ejhf.1020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Considine J, Fox K, Plunkett D, et al. Factors associated with unplanned readmissions in a major Australian health service. Aust Health Rev 2017. 10.1071/AH16287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim Y, Gani F, Lucas DJ, et al. Early versus late readmission after surgery among patients with employer-provided health insurance. Ann Surg 2015;262:502–11. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA 2013;309:355–63. 10.1001/jama.2012.216476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lyle G, Hendrie GA, Hendrie D. Understanding the effects of socioeconomic status along the breast cancer continuum in Australian women: a systematic review of evidence. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:182 10.1186/s12939-017-0676-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Frank M, Sivagnanaratnam A, Bernstein J. Nutritional assessment in elderly care: a MUST!. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2015;4:u204810.w2031 u204810. w2031 10.1136/bmjquality.u204810.w2031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sharma Y, Thompson C, Kaambwa B, et al. Validity of the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) in Australian hospitalized acutely unwell elderly patients. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2017;26:994–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Noordzij M, Leffondré K, van Stralen KJ, et al. When do we need competing risks methods for survival analysis in nephrology? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:2670–7. 10.1093/ndt/gft355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verduijn M, Grootendorst DC, Dekker FW, et al. The analysis of competing events like cause-specific mortality--beware of the Kaplan-Meier method. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26:56–61. 10.1093/ndt/gfq661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Austin PC, Fine JP. Accounting for competing risks in randomized controlled trials: a review and recommendations for improvement. Stat Med 2017;36:1203–9. 10.1002/sim.7215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Austin PC, Fine JP. Practical recommendations for reporting Fine-Gray model analyses for competing risk data. Stat Med 2017;36:4391–400. 10.1002/sim.7501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Feinberg J, Nielsen EE, Korang SK, et al. Nutrition support in hospitalised adults at nutritional risk. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;5:Cd011598 10.1002/14651858.CD011598.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sharma Y, Thompson CH, Kaambwa B, et al. Investigation of the benefits of early malnutrition screening with telehealth follow up in elderly acute medical admissions. QJM 2017;110:639–47. 10.1093/qjmed/hcx095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stratton RJ, Hébuterne X, Elia M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of oral nutritional supplements on hospital readmissions. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12:884–97. 10.1016/j.arr.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cloyd JM, Chen J, Ma Y, et al. Association between weekend discharge and hospital readmission rates following major surgery. JAMA Surg 2015;150:849–56. 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hunter E. Disadvantage and discontent: a review of issues relevant to the mental health of rural and remote Indigenous Australians. Aust J Rural Health 2007;15:88–93. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yong TY, Fok JS, Hakendorf P, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of discharges against medical advice among hospitalised patients. Intern Med J 2013;43:798–802. 10.1111/imj.12109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Conroy SP, Dowsing T, Reid J, et al. Understanding readmissions: an in-depth review of 50 patients readmitted back to an acute hospital within 30days. Eur Geriatr Med 2013;4:25–7. 10.1016/j.eurger.2012.02.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meddings J, Reichert H, Smith SN, et al. The impact of disability and social determinants of health on condition-specific readmissions beyond medicare risk adjustments: a cohort study. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:71–80. 10.1007/s11606-016-3869-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hua M, Gong MN, Brady J, et al. Early and late unplanned rehospitalizations for survivors of critical illness*. Crit Care Med 2015;43:430–8. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zajic P, Bauer P, Rhodes A, et al. Weekends affect mortality risk and chance of discharge in critically ill patients: a retrospective study in the Austrian registry for intensive care. Crit Care 2017;21:223 10.1186/s13054-017-1812-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.