Abstract

Rationale

The majority of current cardiovascular cell-therapy trials use bone marrow progenitor cells (BM PCs) and achieve only modest efficacy; the limited potential of these cells to differentiate into endothelial-lineage cells is one of the major barriers to the success of this promising therapy. We have previously reported that the E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1) is a repressor of neovascularization following ischemic injury.

Objective

We sought to define the role of E2F1 in the regulation of BM PC function.

Methods and Results

Ablation of E2F1 (E2F1−/−) in mouse BM PCs increases oxidative metabolism and reduces lactate production, resulting in enhanced endothelial differentiation. The metabolic switch in E2F1−/− BM PCs is mediated by a reduction in the expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) and PDK2; overexpression of PDK4 reverses the enhancement of oxidative metabolism and endothelial differentiation. Deletion of E2F1 in the BM increases the amount of PC-derived endothelial cells in the ischemic myocardium, enhances vascular growth, reduces infarct size, and improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction.

Conclusion

Our results suggest a novel mechanism by which E2F1 mediates the metabolic control of BM PC differentiation, and strategies that inhibit E2F1 and/or enhance oxidative metabolism in BM PCs may improve the effectiveness of cell therapy.

Keywords: E2F, PDK, bone marrow progenitor cell, oxidative metabolism, myocardial infarction, endothelial progenitor cells, differentiation, stem cell, oxygen consumption

Subject Terms: Cell Therapy, Coronary Artery Disease, Metabolism, Myocardial Regeneration, Stem Cells

INTRODUCTION

The majority of current clinical trials for cardiovascular cell therapy use BM PCs 1, because they are well characterized and include a subpopulation of endothelial PCs (EPCs), which play a crucial role in cardiovascular homeostasis 2. However, despite ample evidence from the literature indicating that the transplanted cells are incorporated into the vasculature and secrete angiogenic growth factors that support the developing microvasculature 3, 4, the clinical efficacy observed in these trials remains modest 1; very few of the transplanted (or mobilized endogenous) PCs differentiate into vascular cells to achieve functional integration and long-term engraftment, and this limited potential for differentiation into endothelial-lineage cells is one of the major barriers to the success of PC therapy 5.

Ischemic injury induces a variety of mechanisms that promote angiogenesis in the injured tissue. This angiogenic environment should, at least in theory, induce the differentiation of PCs into vascular ECs, but very few recruited PCs actually become incorporated into the vasculature and display a true EC phenotype 6. It is known that undifferentiated PCs are relatively quiescent, relying primarily on anaerobic glycolysis for energy production 7; activation (and subsequent differentiation) of the quiescent cells is often accompanied by a metabolic change or “switch” from anaerobic glycolysis to mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (mtOP) 8. Interestingly, recent reports suggest that this metabolic switch is largely controlled by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases 4 and 2 (PKD4/2) 9. PDK4/2 phosphorylate pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which inactivates the PDH complex, and this decline in PDH complex activity limits mtOP 10–12. Intriguingly, when the PDK4/2 genes are deleted in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), the HSCs are forced to switch from anaerobic glycolysis to mtOP, and this change is associated with a marked increase in the number of mature blood cells and decline in the number of HSCs 9; conversely, when mtOP is disrupted by deleting the mitochondrial phosphatase PTPMT1, HSC differentiation is blocked, the number of mature blood cells declines, and HSC numbers increase by ~40-fold 13. These provocative findings encourage us to hypothesize that the failure of BM PCs to assume an EC identity occurs because these cells are not metabolically primed for differentiation; i.e., the cells continue to produce energy primarily through anaerobic glycolysis, which supports quiescence, rather than mtOP, which is required for differentiation, and that priming the metabolic switch in BM PCs at the site of vascular injury may enhance the differentiation of PCs into endothelial-lineage cells and promote cardiovascular repair.

E2F1 is a member of the E2F family transcription factors known for regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis 14. However, evidence from our lab and others suggests that E2F1 is dispensable for vascular growth; rather, loss of E2F1 in mice is protective during ischemic and ischemic reperfusion injuries 15–17. Interestingly, E2F1 has recently been recognized as a major regulator of energy metabolism. In skeletal muscle and adipose tissues, E2F1 suppresses the expression of components in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, and E2F1-deficient (E2F1−/−) mice display elevated exercise endurance and resistance to cold-induced hypothermia 18. Intriguingly, E2F1 has also been shown to bind to PDK4 promoter and activate PDK4 expression in myoblasts 19. However, it is unknown whether E2F1 regulates the metabolism and differentiation of BM PCs and whether this regulation is attributable to the beneficial effect of E2F1 deficiency under ischemic injury.

Here we report that in BM PCs, E2F1 is a potent activator of PDK4/2 gene expression; genetic deletion of E2F1 leads to decreased PDK4/2 expression, increased oxidative metabolism and endothelial differentiation, and enhanced vascular repair after MI. Thus reset of BM PC metabolism via inhibition of E2F1 and/or enhancement of mtOP may provide a novel strategy for enhancing the effectiveness of cell therapy.

METHODS

All materials, methods, and supporting data are available within the article and the online supplementary file.

Mice

The E2F1−/− and Tie2/LacZ mice were obtained and genotyped as we reported previously 16, 17. Age-matched male mice were used. Sample sizes were determined by power calculation with 80% power. The investigators responsible for histological analyses were blinded to surgical groups. Mice were randomly assigned to the experimental groups. All animals were bred, maintained, and operated in the Center for Comparative Medicine of Northwestern University and the Animal Resources Program of the University of Alabama at Birmingham following protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Isolation and culture of BM PCs

BM mononuclear cells (MNCs) were isolated by density gradient centrifugation 20. Lineage-negative (Lin−) PCs were enriched through a lineage cell depletion kit, followed by an additional step to deplete CD31+ cells (Miltenyi Biotec, Cambridge, MA); the final purity (>95%) and amount of CD31+ cells (<0.2%) were confirmed by flow cytometry. The Lin− PCs were either used freshly or maintained in suspension culture with IMDM plus 10% FBS, thrombopoietin (20 ng/mL), stem cell factor (10 ng/mL), and IL-3 (6 ng/mL) (R & D Systems) as we previously described 20.

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) measurements

OCR and ECAR of BM PCs were measured with Seahorse XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). Briefly, Lin− BM PCs were seeded in 100 μL culture medium at a density of 5 × 105/well in XF24 24-well cell culture plate coated with BD Cell-Tak (BD Biosciences) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Following cell attachment, an additional 400 μL medium was added to each well, and incubated at 37°C overnight. Prior to analysis, the medium was gently removed and replaced with 500 μL pre-warmed specially formulated Seahorse DMEM (Seahorse Bioscience) supplemented with 10 mM glucose (assay medium) and incubated at 37°C without CO2 for 1 h. Following calibration of the XF24 sensor cartridge, the cell culture plate was placed in the analyzer and the ECAR and OCR were simultaneously measured. ECAR and OCR rates were normalized to cell numbers.

In vitro differentiation assay

BM MNCs were cultured on vitronectin-coated flasks in EGM-2 medium supplemented with endothelial growth factor cocktail SingleQuots (Clonetics, San Diego, CA) 21. After 4d culture, non-adherent cells were removed, and new medium was applied. The adherent cells were maintained for a total of 7d before phenotypic and functional assessments.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR was performed as we described previously 20. Primer sequences for genes encoding for Atp5g1, Cox5a, Ndufv1, Sdha, Uqcr, Idh3a, Ucp2, PGK, PDK1-4, E2F1-8, and β-actin were reported in Online Table I. The results were normalized to the mRNA levels of β-actin or 18S.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted in cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) and analyzed with Western blotting by using rabbit anti-PDK4 antibody (1:500; Abcam), rabbit anti-PDK2 and anti-phospho-PDH antibodies (1:250; Santa Cruz), and rabbit anti-β-actin and anti-α-tubulin antibodies (1:3000; Cell Signaling Technology). The intensities of protein bands were quantified densitometrically by using the NIH IMAGE software.

Flow cytometry

BM PC-derived ECs were blocked with mouse Fc blocker, stained with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse CD31 and PE-conjugated anti-mouse Flk-1 antibodies (BD Biosciences), and analyzed on a FACSCantoII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences), as we described elsewhere 21.

Lentiviral vectors and BM PC transduction

The vector backbone plasmid LeGo-iC2 (control-mCherry) was purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). The mouse PDK4 cDNA on pCMV6-PDK4 was purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD) and cloned into LeGo-iC2 to generate LeGo-PDK4 (PDK4-mCherry) by using the EcoR I and Not I restriction sites. To produce lentiviral vectors, the backbone plasmids were co-transfected, separately, with envelope (pMD2.G) and packaging (psPAX2) plasmids 22 into 293FT cells; 2d later, virus-containing supernatants were collected and concentrated by ultracentrifugation 22. To infect BM PCs, the lentivirus were applied to the cells (MOI: 50) with polybrene (8 ug/mL final concentration). The medium was replaced on the following day, and the cells were cultured for an additional 3 days before FACS sorting for the transduced cells based on mCherry expression.

BM transplantation (BMT)

To evaluate the role of BM E2F1 in the ischemic cardiac repair, BMT was performed to reconstitute the BM of lethally-irradiated WT mice with E2F1-knockout/eGFP-transgenic (E2F−/−eGFP) or eGPF (control) donor BM-MNCs 21. Eight weeks after BMT, the engraftment was assessed by FACS for the proportion of eGFP-expressing peripheral blood MNCs cells isolated from ~100 uL tail-bleed. The recipients with an engraftment >90% were chosen for surgical induction of MI.

Surgical induction of MI and echocardiography

MI was induced in mice by permanent ligation in the middle of the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery 23. Trans-thoracic 2-dimensional echocardiographic measurements were performed before MI (baseline) and at 7, 14 and 28 days post-MI by using a Vevo 770TM high-resolution ultrasound biomicroscope (VisualSonics Inc, Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and Vevo analysis software (Vevo 2.2.3; VisualSonics Inc) 23. Mice were lightly anesthetized with inhaled 2% Isofluorane, and heart rates were maintained at 400 to 500 beats per minute. M-Mode and B-Mode images were recorded, and left ventricular fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) were calculated 23.

Histological assessments

Cardiac tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 4 h, then snap-frozen. Serial cryosectioning was performed starting at 1 mm below the suture (used to ligate the LAD) moving toward the apex, with three consecutive sections per 1 mm to allow for quantitative pathohistological analysis at each level 23. The Masson Trichrome elastic tissue staining was performed, and infarct size was reported as the ratio of the length of fibrotic area to the length of the LV inner circumference. To evaluate PC endothelial differentiation and capillary density, immunohistochemical staining was performed using fluorescent anti-BS Lectin 1 (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) and anti-CD31 (Santa Cruz) antibodies 16, 21, 23; 3 sections per ischemic heart and 6 fields per section were examined. All surgical procedures and pathohistological analyses were performed by investigators blinded to treatment assignments.

Statistical analyses

All values are reported as mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare two means. One-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni correction was used to compare multiple (>2) means with one or two independent variables respectively. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

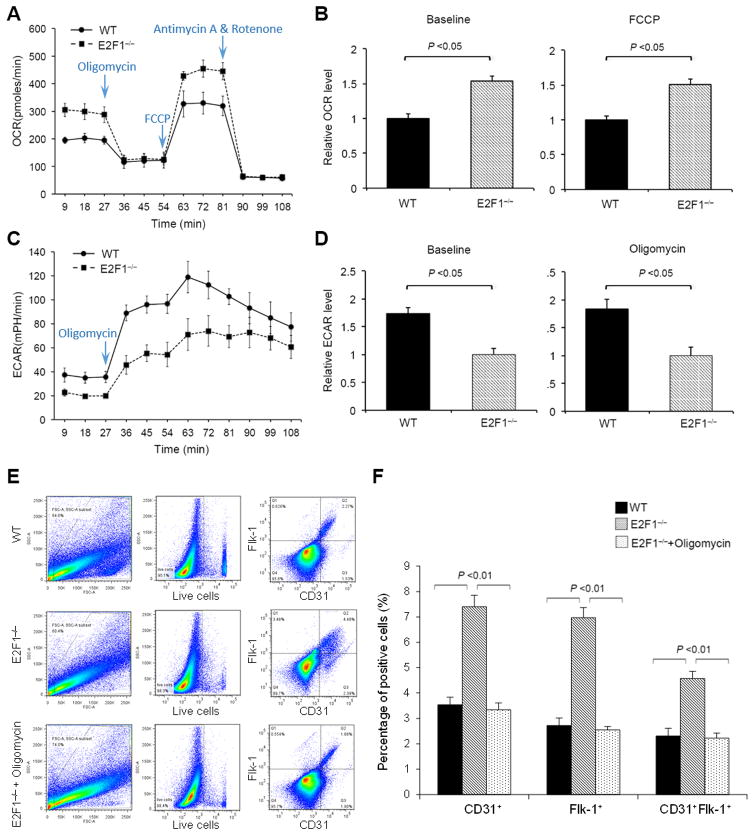

E2F1 deficiency increases OCR and decrease ECAR in BM PCs

We firstly isolated Lin− BM PCs from E2F1−/− and WT mice and measured OCR at baseline and after sequential treatments with F1F0 ATP synthase inhibitor Oligomycin, uncoupler FCCP, and electron-transport-chain blocker Antimycin A plus Rotenone. Compared to WT PCs, E2F1−/− PCs displayed a significantly greater OCR; the basal and maximum (FCCP-induced) OCR in E2F1−/− PCs were elevated by 53.8% and 50.4%, respectively (Figure 1A & 1B). Treatment with Oligomycin or with Antimycin A plus Rotenone abrogated the differences in OCR between the two groups of cells. In contrast, the ECAR level was lowered in E2F1−/− PCs by 73.5% at baseline and by 83.6% with Oligomycin treatment (Figure 1C & 1D). We then measured the level of lactate, the end product of anaerobic glycolysis, and the activity of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), a rate-limiting enzyme of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP), in these cells. Consistent with the reduced ECAR level, the lactate level was significantly lower in E2F1−/− BM PC than in WT cells (Online Figure IA). The G6PDH activities, however, were similar between the two groups of cells (Online Figure IB). Thus, endogenous E2F1 expression appears to suppress mtOP and promote anaerobic metabolism of pyruvate without altering PPP in BM PCs.

Figure 1. E2F1−/− BM PCs display an increased OCR, decreased ECAR, and enhanced differentiation into endothelial-lineage cells.

(A) OCR of freshly-isolated WT and E2F1−− BM PCs at basal condition and in response to treatments with Oligomycin (2.5 uM), FCCP (10 uM), and Rotenone (2 uM) plus Antimycin (2 uM). n = 5 per group. (B) Quantification of OCR at basal condition (left panel) and after FCCP treatment (right panel). n = 5 per group. (C–D) ECAR measurements (C) and quantification (D) in WT and E2F1−/− BM PCs at basal condition and after Oligomycin treatment. n = 5 per group. (E–F) Flow cytometry analyses (E) and quantification (F) of CD31 and Flk-1 expression in WT and E2F1−/− BM PCs after differentiation culture with or without Oligomycin for 7d. n = 5 per group.

E2F1 deficiency and mtOP elevation promotes the differentiation of BM PCs into endothelial-lineage cells

Since increased oxidative metabolism has been linked to PC differentiation, we performed an endothelial differentiation assay by culturing same number of E2F1−/− and WT BM PCs (CD31+ cell depleted Lin− BM-MNCs) in the differentiation media for 7d. A markedly greater proportion (Figure 1E & 1F) and absolute number (Online Figure II) of CD31+, Flk-1+, and CD31+Flk-1+ endothelial (lineage) cells were generated from E2F1−/− PCs than from WT PCs, though the initial Lin−CD31+ and Lin−Flk-1+ populations were all at low level and similar between E2F1−/− and WT BM (Online Figure III and Table II). We then isolated CD31+ ECs by FACS and analyzed their function with a tube-formation assay on matrigel; there was no difference in the tube-formation activities between E2F1−/− and WT ECs (Online Figure IV). In addition, the proliferative capacity, the degree of H2O2-induced apoptosis, and chemokine-induced migration were all similar between E2F1−/− and WT PCs (Online Figures V & VI).

To determine whether loss of E2F1 in BM PCs increase their differentiation in vivo, we performed experiments in which Lin− BM PCs were isolated from Tie2/LacZ;E2F1−/− or Tie2/LacZ (control) mice, depleted of Tie2+ cells, mixed in Matrigel and s.c. implanted into WT mice for 5d. This model provided us with the opportunity to quantify endothelial differentiation in vivo, defined by the advent of Tie2 driven LacZ expression. Notably, the ratio of X-gal+ to total cells was 2 times greater in the Matrigel-plugs containing Tie2-LacZ;E2F1−/− BM PCs than in the Matrigel-plugs containing Tie2-LacZ BM PCs (Online Figure VII), these data further support that loss of E2F1 enhances de novo PC endothelial differentiation.

To determine whether the enhanced differentiation capacity of E2F1−/− PCs is mediated by the altered metabolic activity, we suppressed mtOP in E2F1−/− and WT BM PCs by adding Oligomycin to the differentiation medium. Oligomycin treatment significantly reduced the numbers of CD31+ and Flk-1+ E2F1−/− cells to levels that did not differ significantly from the numbers of CD31+ and Flk-1+ cells observed in the WT population (Figure 1F). These results suggest that the elevation in oxidative metabolism is responsible for the increased endothelial differentiation in E2F1−/− PCs. Notably, siRNA-mediated acute knockdown of E2F1 in BM PCs also led to a significant increase in mtOP and endothelial differentiation (Online Figure VIII), confirming that the observations made in E2F1−/− PCs were not the result of developmental adaptation from the knockout mice. Furthermore, the expression levels of E2F2–8 were similar between E2F1−/− and WT BM PCs; thus, it is unlikely that other E2F members have contributed to the enhanced mtOP and endothelial differentiation in E2F1−/− BM PCs (Online Figure IX).

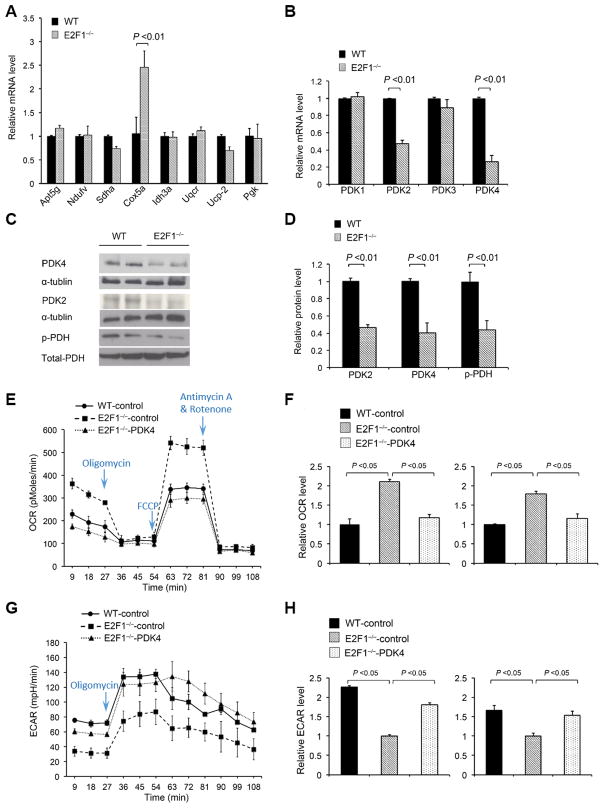

PDK4 and PDK2 are downregulated in E2F1−/− PCs

To identify molecular mechanism by which E2F1 deficiency promotes oxidative metabolism and endothelial differentiation, we analyzed WT and E2F1−/− BM PCs for the mRNA expression of genes involved in the regulation of glycolysis (Pgk), mitochondria respiration (Atp5g1, Cox5a, Ndufv1, Sdha, Uqcr), tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Idh3a), and uncoupling respiration (Ucp2), but found no significant difference between the two groups of cells, except Cox5a expression which was about 2-fold greater in E2F1−/− PCs than in WT PCs (Figure 2A). Because E2F1 has been shown to bind to PDK promoter and PDKs act to limit mtOP by inactivating the PDH complex, we sought to determine whether E2F1 regulates PDK isoenzymes. While PDK1 and PDK3 expression was similar between the two groups of cells, PDK2 and PDK4 mRNA levels were markedly lower in E2F1−/− PCs than in WT PCs (Figure 2B). Our chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays confirm that E2F1 occupies the promoter regions of PDK4 and PDK2 that contain the canonical E2F binding site, suggesting that E2F1 likely directly regulates PDK4 and PDK2 transcription (Online Figure X). Western-blotting analyses confirmed that the protein levels of PDK4 and PDK2 were markedly reduced in E2F1−/− PCs (Figure 2C & 2D), and so was the level of the PDK4/2’s catalytic product, phospho-PDH-E1α (Figure 2C & 2D).

Figure 2. E2F1 suppresses BM PC oxidative metabolism via PDK4/2 expression.

(A–B) qRT-PCR analyses for mRNA expression of representative glycolysis and mitochondrial genes (A) and PDK genes (B) in WT and E2F1−/− BM PCs. The expression levels of individual genes were normalized to the β-actin mRNA and expressed relative to their levels in WT cells. n = 5 per group. (C–D) Western-blotting analyses (C) and quantification (D) of PDK2, PDK4 and phospho-PDH protein levels in BM PCs. n = 4 per group. (E–F) OCR measurements (E) and quantification (F, left panel, at basal condition; right panel, after FCCP injection) in WT and E2F1−/− PCs transduced with control-mCherry lentivirus and in E2F1−/− PCs transduced with PDK4-mCherry lentivirus. n = 5 per group. (G–H) ECAR measurements (G) and quantification (H, left panel, at basal condition; right panel, after Oligomycin treatment) in WT and E2F1−/− PCs transduced with control-mCherry lentivirus and in E2F1−/− PCs transduced with PDK4-mCherry lentivirus. n = 5 per group.

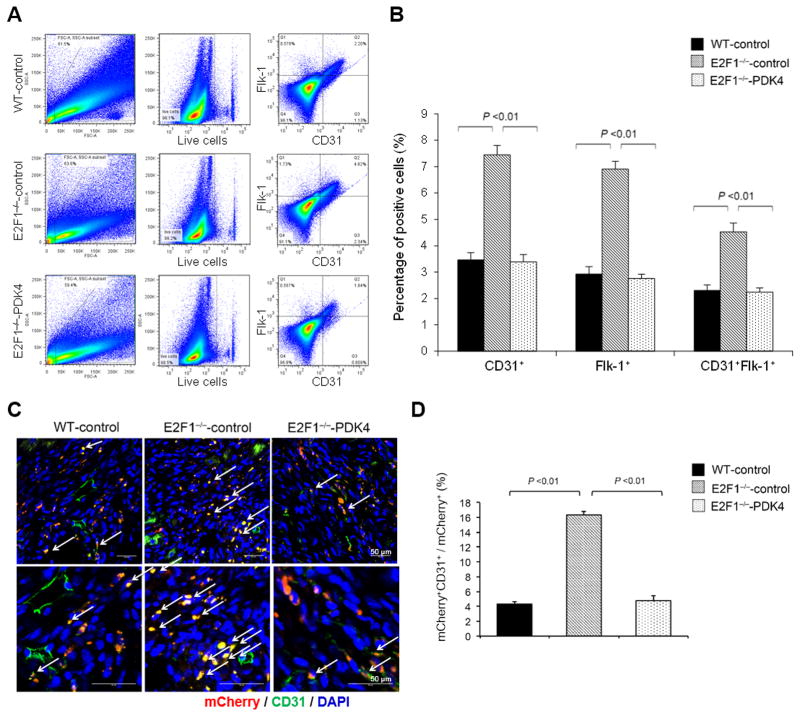

The enhancement in mtOP and endothelial differentiation in E2F1−/− PCs is mediated by the reduced PDK4/2 expression

To determine whether the increased oxidative metabolism of E2F1−/− PCs is mediated by reduced PDK4/2 expression, we transduced control-mCherry lentivirus in WT and E2F1−/− BM PCs and PDK4-mCherry lentivirus into E2F1−/− BM PCs, and 72 h later, FACS-sorted the transduced cells by mCherry expression (Online Figure XI). PDK4 overexpression reversed the increase in OCR (at baseline and with FCCP treatment) (Figure 2E & 2F) and the decrease in ECAR (at baseline and with Oligomycin treatment) (Figure 2G & 2H) observed in the E2F1−/− BM PCs. These results suggest that the increased mtOP in E2F1−/− BM PCs is likely the result of PDK4/2 reduction. Notably, in the endothelial differentiation assay PDK4 overexpression also significantly reduced the number of CD31+ and Flk-1+ E2F1−/− cells and abrogated the difference between E2F1−/− and WT cells (Figure 3A & 3B).

Figure 3. Ablation of E2F1 enhances endothelial differentiation of BM PCs via downregulation of PDK4/2.

WT and E2F1−/− PCs were infected with control-mCherry lentivirus or PDK4-mCherry lentivirus and 3d later, sorted for the transduced cells based on mCherry expression by FACS. (A–B) The sorted PCs were cultured in EPC differentiation medium for 7d, then analyzed by flow cytometry for CD31 and Flk-1 expression (A, representative; B, quantification). n = 4 per group. (C–D) The sorted PCs were i.v. injected to WT mice immediately after surgical induction of MI; 7d later, the mice were euthanized and the cardiac tissues were stained for CD31 (green) to identify the ECs derived from the injected PCs (red) (C, representative; D, quantification). n = 8 per group.

E2F1 deficiency increases the proportion of PC-derived ECs incorporated in the ischemic myocardium

Because the differentiation of recruited BM PCs into endothelial-lineage cells is crucial for de novo vasculogenesis, we evaluated whether E2F1 influences the contribution of BM PCs to vascular growth. The control-mCherry or PDK4-mCherry transduced WT or E2F1−/− PCs were i.v. injected into WT mice immediately after surgical-induction of MI, and 7d later, the cells that differentiated into endothelial lineage were assessed by double positive for mCherry expression and CD31 staining. In the infarct border zone (i.e., ischemic and ischemic reperfusion area), while the total numbers of recruited mCherry+ cells were similar (Online Figure XII), the proportion of ECs derived from control-mCherry–transduced E2F1−/− PCs was 3 times greater than ECs derived from control-mCherry–transduced WT PCs (Figure 3C & 3D). Notably, the proportion of ECs derived from PDK4-mCherry–transduced E2F1−/− PCs were markedly lower than ECs from control-mCherry–transduced E2F1−/− PCs (Figure 3C & 3D). Collectively, the results from our in vivo and in vitro experiments suggest that endogenous E2F1 expression impedes the differentiation of BM PCs into endothelial-lineage cells in a PDK-dependent manner.

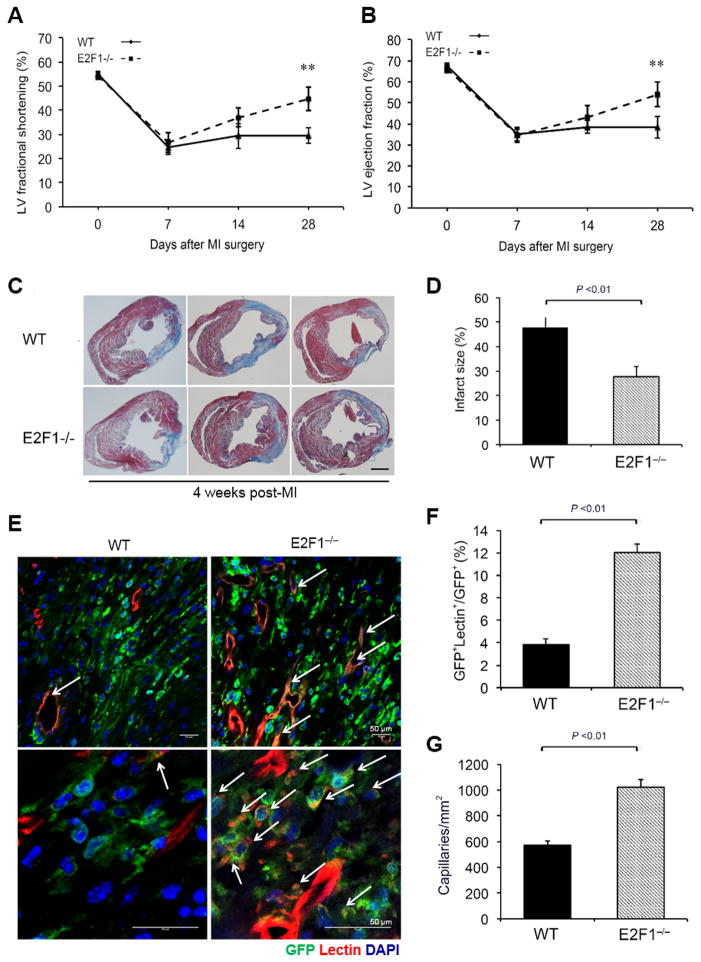

Ablation of E2F1 in BM PCs enhances vascular growth, reduces infarct size, and improves cardiac function after MI

To determine the role of E2F1 in BM PC-mediated cardiac repair, we isolated BM mononuclear cells (MNCs) from E2F1−/−eGFP and WTeGFP mice and transplanted (separately) into lethally irradiated WT mice; 8 weeks later, we surgically induced myocardial infarction (MI) in the recipients with a BM engraftment over 90% (Online Figure XIII). On day 28 post-MI, left-ventricular (LV) fraction shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF) were significantly greater (Figure 4A & 4B) and infarct size was significantly smaller (Figure 4C & 4D) in mice with E2F1−/−eGFP BM than in mice with WTeGFP BM. To assess endothelial differentiation and angiogenesis of BM PCs in the ischemic myocardium, MI mice were perfused with lectin-Rhodamine to identify function vessels. At the ischemic region, the proportion of GFP+ cells that also incorporated the lectin stain was significantly greater in mice with E2F1−/−eGFP BM than in mice with WTeGFP BM, which suggests that E2F1 deficiency promotes the differentiation of BM cells into ECs (Figure 4E & 4F). In addition, mice with E2F1−/−eGFP BM demonstrated a significantly higher capillary density than mice with WTeGFP BM. Collectively, these results suggest that ablation of E2F1 enhances BM PC-mediated ischemic cardiac repair.

Figure 4. Ablation of E2F1 in BM PCs improves PC-mediated cardiac repair.

BMT was performed using E2F1−/−eGFP or eGFP mouse BM to reconstitute WT mouse BM, and 8 weeks later, MI was induced surgically in the recipient mice with an engraftment over 90%, followed by serial assessments. (A–B) Echocardiography was performed at various time points post-MI to evaluate cardiac function, left ventricular (LV) fraction shortening (A) and ejection fraction (B). n = 10 per group, **P <0.01 vs. WT. (C–D) Representative Masson’s Trichrome staining (c) and quantification of infarct size (D) at 4 weeks post-MI. The infarct size is expressed as the percentage of the length of fibrotic area to the length of the LV inner circumference. n = 10 per group. Scale bar, 1mm. (E–G) After last non-invasive physiological measurements at 4 weeks post-MI, the mice were perfused with Lectin-Rhodamine and euthanized. (E) Representative immunofluorescent images of the ischemic myocardium at the infarct border zone. Arrow: BM-derived ECs double positive for eGFP and Rhodamine showing yellow. (F) The percentage of GFP and lectin double positive cells in periinfarct myocardium 4 weeks after MI. n = 10 per group. (G) Capillary density in periinfarct myocardium 4 weeks post-MI. n = 10 per group.

DISCUSSION

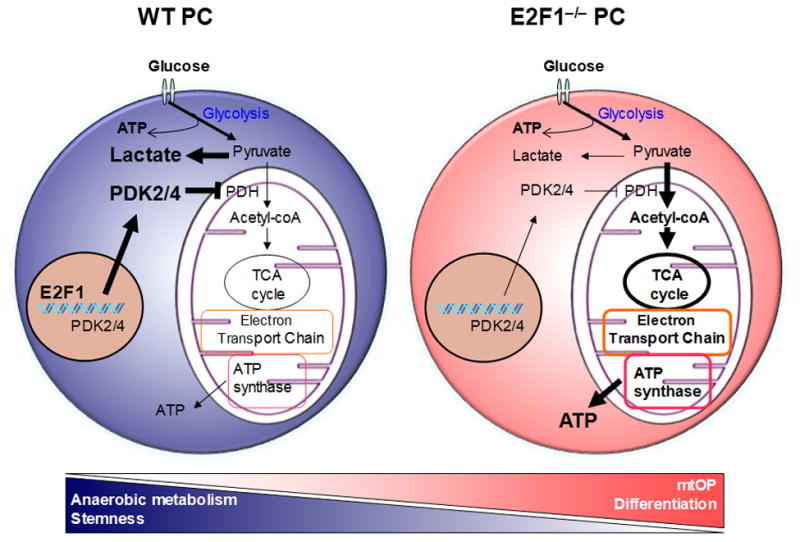

In this study, we have identified a novel mechanism by which E2F1, a transcription factor and classic cell-cycle regulator, suppresses BM PC oxidative metabolism and endothelial differentiation through expression of the glycolysis enzymes PDK4/2 (Figure 5). Compared to WT BM PCs, E2F1−/− BM PCs express less PDK4/2, consume more oxygen, and differentiate more readily into endothelial-lineage cells; and all these effects can be reversed by PDK4 overexpression. Remarkably, replacement of WT BM with E2F1−/− BM in mice significantly increases the contribution of BM PCs to new vessel formation, reduces infarct size, and improves cardiac function after MI. Thus, E2F1-mediated metabolic control impedes adult BM PCs from responding to angiogenic cues in the ischemic myocardial tissue. The experiments described in this report comprise the first investigation of the relationship between the metabolic state and endothelial differentiation in BM PCs. Our results are consistent with recent reports, suggesting that metabolism can critically determine the stem cell fate 9, 24, and that modulation of BM PC metabolism may hold promise for enhancing the effectiveness of cardiovascular cell therapy.

Figure 5. E2F1 suppresses BM PC mtOP and endothelial differentiation.

(Left panel) In BM PCs, E2F1 promotes PDK4 and PDK2 expression, which in turn repress PDH activity and mtOP to favor anaerobic metabolism, permitting BM PC maintenance and stemness. (Right panel) Deletion or inhibition of E2F1 reduces PDK4 and PDK2 expression, which de-repress PDH activity and result in a metabolic switch to mtOP, promoting BM PC differentiation into vascular endothelial cells that contribute to the ischemic tissue repair.

The significance of E2F1 and PDK4/2 in ischemic heart disease has been increasingly recognized in last several years 25. E2F1 is upregulated in ischemic human hearts 26, and infarct sizes are remarkably reduced when E2F1 is genetically deleted in murine models of MI 17 and myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury 15. PDK4/2 are also crucially involved in the pathogenesis of ischemic cardiac injury, and strategies that target PDK4/2 have recently been proposed for the treatment of diabetes and diabetic cardiomyopathy 27–29. Thus, both E2F1 and PDK4/2 are deregulated in patients with ischemic heart disease and diabetes, and our findings suggest that E2F1–PDK4/2 may be an important metabolic pathway in BM PCs that underlies the functional impairment of EPCs in these patients 30. This new understanding have implications not just for cell therapy, but also for enhancing the reparative potential of patients’ endogenous PC population.

Recently Blanchet et al have shown that E2F1 deficiency results in an elevated mtOP in skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissues via upregulating genes in the mitochondrial respiratory chain 18. In this current study, we confirmed that mtOP is also elevated in the E2F1−/− BM PCs; but intriguingly, this is mediated by reduced PDK4/2 expression, which highlights the tissue-specificity of E2F1 targets. Given the largely overlapping phosphorylation sites on PDH between PDK4 and PDK2 11, it is not surprising that overexpressing PDK4 alone can reverse the effect of both PDK4 and PDK2 downregulation.

Intriguingly, a downregulation of PDK4/PDK2 in E2F1−/− PCs did not alter the baseline hematopoietic lineage differentiation in the BM, as evidenced by our hematopoietic lineage analyses and BM transplantation assays. However, it should be noted that a complete deletion of both PDK4 and PDK2 indeed enhances hematopoietic lineage differentiation9. Thus, the degrees of PDK4/PDK2 downregulation needed for endothelial differentiation under angiogenic stress and for hematopoietic lineage differentiation in the BM are different. These observations highlight the difference in the cellular programs of these two developmentally-related but functionally-distinct cell types. In addition, the site of ischemic injury and the BM stem-cell niche are distinct microenvironments 31, and it is possible that the cellular effect of E2F1-deficiency is differentially counteracted by their environmental signals; this hypothesis however is beyond the scope of this current study and remains a subject of our future investigations.

In addition, we and others have previously shown that loss of E2F1 in mice protects limb and cardiac tissues from ischemic and ischemic reperfusion injuries via increased expression of angiogenic factors (including VEGF) and reduced apoptosis, respectively 15–17. Thus it is likely that both VEGF upregulation (paracrine effect) and PDK2/4 downregulation (autonomous effect) contribute to the enhanced neovascularization in E2F1−/− animals. However, it should be noted that the exaggerated VEGF upregulation in E2F1−/− mice occurs primarily during ischemic insults, neither a high vascularity nor perturbation of bone marrow niche was observed in these animals 16 (Online Figure XIV). More importantly, E2F1−/− BM PCs display a significantly greater differentiation capacity in a “super-physiological” concentration of VEGF (i.e., much higher than the level of VEGF secreted from cells) in our differentiation assays, which suggests that the E2F1/PDK4-mediated control of PC differentiation is likely independent of VEGF effect.

Relative to many other cell types, vascular ECs display a higher rate of glycolysis and lower rate of mitochondrial respiration, and increased glycolysis driven by PFKFB3 overexpression in ECs enhances vessel sprouting and tip cell function 32. These observations, although fascinating, should not detract the regulatory role of mitochondrial respiration, which has been associated with the differentiation of various stem/progenitor cells 33. Importantly, it is still unclear how glycolysis flux affects tip cell function and what intermediate metabolites are involved in the regulation. Conceivably, tip cells and EPCs have different cellular environment; and sprouting and differentiation have different energy demands and require different metabolites-induced signaling pathways.

E2F1 is a classic regulator of cell-cycle progression and apoptosis 34. However, unlike in cancer cells, deletion of E2F1 in BM PCs does not affect proliferation or apoptosis. These results are consistent with our previous observations in ECs that E2F1 is dispensable for EC proliferation and apoptosis while E2F3 is essential for EC growth and angiogenesis 16, 17, 35. These observations highlight the cell-type dependent actions of E2F family of transcription factors in the cardiovascular system.

Although our data have clearly established the role of E2F1 and the E2F1–PDK4/2 pathway in PC oxidative metabolism and endothelial differentiation, specific metabolites are yet to be identified. Multiple metabolic changes downstream of PDK/PDH, including the metabolic intermediates of mtOP, may potentially contribute to the regulation of PC differentiation and modification of cell phenotype. Emerging evidence now suggests that metabolites can regulate cell function by acting as cofactors or substrates for key enzymes of epigenetic modifications. For example, Acetyl-CoA, the fuel of TCA cycle, is a substrate used by histone acetyltransferase enzymes to modify histone tails of chromatins in eukaryotic cells 36, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), a key electron carrier of mtOP, is consumed by the class III histone deacetylases as a cofactor 37. In addition, the metabolic changes can alter epigenetic modifications by changing the concentration of those substrates, which eventually lead to phenotype modifications of cells 38. Furthermore, other products and enzymes associated with mtOP, like ROS 39 (Online Figure XV) and ATP synthase 40, may also contribute to the PC differentiation. Importantly, the enhancement of differentiation of E2F1−/− BM PCs might not be limited to endothelial-lineage; thus a thorough analysis of potential PC differentiation to other lineage cells are warranted.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the E2F1–PDK4/2 pathway critically controls oxidative metabolism and endothelial differentiation in BM PCs and may be a novel therapeutic target for enhancing the effectiveness of cell therapy for ischemic heart disease.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Adult bone marrow progenitor cells (BM PCs) have differentiation potential into endothelial cell lineage; however, little evidence suggests their de novo vasculogenesis in the ischemic tissue.

The efficacy of cell therapy is modest and attributed to paracrine mechanisms.

Deletion or inhibition of E2F1 is protective of ischemic injury.

The differentiation of stem/progenitor cells is associated with an increase in oxidative metabolism.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Deletion of E2F1 in BM PCs augments oxidative metabolism, which promotes endothelial differentiation.

E2F1 suppresses oxidative metabolism by increasing pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) and PDK2 expression.

Deletion of E2F1 in BM enhances PC-mediated vasculogenesis and cardiac repair after myocardial infarction.

Modulation of E2F1–PDK4/2 pathway or oxidative metabolism in BM PCs may enhance the effectiveness of cell therapy.

Clinical outcomes of cell therapy for ischemic heart disease have been unsatisfactory thus far. One of the major barriers to success is that the capacity of de novo vasculogenesis of PCs has not been realized, as limited number of BM PCs actually become vascular endothelial cells and incorporated into the vessels. In this study, we found that deletion of the E2F1 transcription factor in BM PCs enhances endothelial differentiation by increased oxidative metabolism, and that E2F1 suppresses oxidative metabolism by increasing PDK4 and PDK2 expression. Deletion of E2F1 in the BM enhances PC-mediated vasculogenesis in the infarcted myocardium and improves the cardiac repair and functional recovery. Our findings suggest that the E2F1–PDK4/2 pathway, or oxidative metabolism in general, may serve as a novel target for improving the effectiveness of cardiovascular cell therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul T Schumacker (Northwestern University) for insightful suggestions.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (R01 Grants# HL093439, HL113541, HL131110, and HL138990 to G.Q.); American Diabetes Association (Grant# 1-15-BS-148 to G.Q.); American Heart Association (Grant# 13PRE14710033 to S.X.); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant# 31530023 to J.T.); the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant# 81100084 to M.C.); and the National Key R & D Program (Grant# 2016YFA0101100 to N.G.D).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BM

bone marrow

- ECAR

extracellular acidification rate

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cells

- IF

immunofluorescence

- IL

interleukin

- LAD

left anterior descending

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVFS

left ventricular fractional shortening

- LVEDV

left ventricular end-diastolic volume

- LVESV

left ventricular end-systolic volume

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MNC

mononuclear cell

- mtOP

mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- PC

progenitor cell

- PPP

pentose phosphate pathway

- qPCR

quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.Afzal MR, Samanta A, Shah ZI, Jeevanantham V, Abdel-Latif A, Zuba-Surma EK, Dawn B. Adult bone marrow cell therapy for ischemic heart disease: Evidence and insights from randomized controlled trials. Circulation research. 2015 doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304792. pii: CIRCRESAHA.114.304792 Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill JM, Zalos G, Halcox JP, Schenke WH, Waclawiw MA, Quyyumi AA, Finkel T. Circulating endothelial progenitor cells, vascular function, and cardiovascular risk. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348:593–600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawamoto A, Tkebuchava T, Yamaguchi J, Nishimura H, Yoon YS, Milliken C, Uchida S, Masuo O, Iwaguro H, Ma H, Hanley A, Silver M, Kearney M, Losordo DW, Isner JM, Asahara T. Intramyocardial transplantation of autologous endothelial progenitor cells for therapeutic neovascularization of myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2003;107:461–468. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000046450.89986.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahoo S, Klychko E, Thorne T, Misener S, Schultz KM, Millay M, Ito A, Liu T, Kamide C, Agrawal H, Perlman H, Qin G, Kishore R, Losordo DW. Exosomes from human cd34(+) stem cells mediate their proangiogenic paracrine activity. Circulation research. 2011;109:724–728. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimmeler S, Ding S, Rando TA, Trounson A. Translational strategies and challenges in regenerative medicine. Nature medicine. 2014;20:814–821. doi: 10.1038/nm.3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gu E, Chen WY, Gu J, Burridge P, Wu JC. Molecular imaging of stem cells: Tracking survival, biodistribution, tumorigenicity, and immunogenicity. Theranostics. 2012;2:335–345. doi: 10.7150/thno.3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simsek T, Kocabas F, Zheng J, Deberardinis RJ, Mahmoud AI, Olson EN, Schneider JW, Zhang CC, Sadek HA. The distinct metabolic profile of hematopoietic stem cells reflects their location in a hypoxic niche. Cell stem cell. 2010;7:380–390. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung S, Dzeja PP, Faustino RS, Perez-Terzic C, Behfar A, Terzic A. Mitochondrial oxidative metabolism is required for the cardiac differentiation of stem cells. Nature clinical practice. Cardiovascular medicine. 2007;4(Suppl 1):S60–67. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takubo K, Nagamatsu G, Kobayashi CI, Nakamura-Ishizu A, Kobayashi H, Ikeda E, Goda N, Rahimi Y, Johnson RS, Soga T, Hirao A, Suematsu M, Suda T. Regulation of glycolysis by pdk functions as a metabolic checkpoint for cell cycle quiescence in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell stem cell. 2013;12:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplon J, Zheng L, Meissl K, Chaneton B, Selivanov VA, Mackay G, van der Burg SH, Verdegaal EM, Cascante M, Shlomi T, Gottlieb E, Peeper DS. A key role for mitochondrial gatekeeper pyruvate dehydrogenase in oncogene-induced senescence. Nature. 2013;498:109–112. doi: 10.1038/nature12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korotchkina LG, Patel MS. Site specificity of four pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzymes toward the three phosphorylation sites of human pyruvate dehydrogenase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:37223–37229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contractor T, Harris CR. P53 negatively regulates transcription of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase pdk2. Cancer research. 2012;72:560–567. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu WM, Liu X, Shen J, Jovanovic O, Pohl EE, Gerson SL, Finkel T, Broxmeyer HE, Qu CK. Metabolic regulation by the mitochondrial phosphatase ptpmt1 is required for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Cell stem cell. 2013;12:62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H-Z, Tsai S-Y, Leone G. Emerging roles of e2fs in cancer: An exit from cell cycle control. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:785–797. doi: 10.1038/nrc2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angelis E, Zhao P, Zhang R, Goldhaber JI, Maclellan WR. The role of e2f-1 and downstream target genes in mediating ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;51:919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin G, Kishore R, Dolan CM, Silver M, Wecker A, Luedemann CN, Thorne T, Hanley A, Curry C, Heyd L, Dinesh D, Kearney M, Martelli F, Murayama T, Goukassian DA, Zhu Y, Losordo DW. Cell cycle regulator e2f1 modulates angiogenesis via p53-dependent transcriptional control of vegf. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:11015–11020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509533103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu M, Zhou J, Cheng M, Boriboun C, Biyashev D, Wang H, Mackie A, Thorne T, Chou J, Wu Y, Chen Z, Liu Q, Yan H, Yang Y, Jie C, Tang YL, Zhao TC, Taylor RN, Kishore R, Losordo DW, Qin G. E2f1 suppresses cardiac neovascularization by down-regulating vegf and plgf expression. Cardiovascular research. 2014;104:412–422. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanchet E, Annicotte JS, Lagarrigue S, Aguilar V, Clape C, Chavey C, Fritz V, Casas F, Apparailly F, Auwerx J, Fajas L. E2f transcription factor-1 regulates oxidative metabolism. Nature cell biology. 2011;13:1146–1152. doi: 10.1038/ncb2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hsieh MC, Das D, Sambandam N, Zhang MQ, Nahle Z. Regulation of the pdk4 isozyme by the rb-e2f1 complex. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:27410–27417. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802418200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng M, Zhou J, Wu M, Boriboun C, Thorne T, Liu T, Xiang Z, Zeng Q, Tanaka T, Tang YL, Kishore R, Tomasson MH, Miller RJ, Losordo DW, Qin G. Cxcr4-mediated bone marrow progenitor cell maintenance and mobilization are modulated by c-kit activity. Circulation research. 2010;107:1083–1093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.220970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin G, Ii M, Silver M, Wecker A, Bord E, Ma H, Gavin M, Goukassian DA, Yoon YS, Papayannopoulou T, Asahara T, Kearney M, Thorne T, Curry C, Eaton L, Heyd L, Dinesh D, Kishore R, Zhu Y, Losordo DW. Functional disruption of alpha4 integrin mobilizes bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitors and augments ischemic neovascularization. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:153–163. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szulc J, Wiznerowicz M, Sauvain MO, Trono D, Aebischer P. A versatile tool for conditional gene expression and knockdown. Nat Methods. 2006;3:109–116. doi: 10.1038/nmeth846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang YL, Zhu W, Cheng M, Chen L, Zhang J, Sun T, Kishore R, Phillips MI, Losordo DW, Qin G. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances the benefit of cardiac progenitor cell therapy for treatment of myocardial infarction by inducing cxcr4 expression. Circulation research. 2009;104:1209–1216. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gan B, Hu J, Jiang S, Liu Y, Sahin E, Zhuang L, Fletcher-Sananikone E, Colla S, Wang YA, Chin L, Depinho RA. Lkb1 regulates quiescence and metabolic homeostasis of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2010;468:701–704. doi: 10.1038/nature09595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yurkova N, Shaw J, Blackie K, Weidman D, Jayas R, Flynn B, Kirshenbaum LA. The cell cycle factor e2f-1 activates bnip3 and the intrinsic death pathway in ventricular myocytes. Circulation research. 2008;102:472–479. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.164731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wohlschlaeger J, Schmitz KJ, Takeda A, Takeda N, Vahlhaus C, Stypmann J, Schmid C, Baba HA. Reversible regulation of the retinoblastoma protein/e2f-1 pathway during “reverse cardiac remodelling” after ventricular unloading. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation: the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2010;29:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ussher JR, Wang W, Gandhi M, Keung W, Samokhvalov V, Oka T, Wagg CS, Jaswal JS, Harris RA, Clanachan AS, Dyck JR, Lopaschuk GD. Stimulation of glucose oxidation protects against acute myocardial infarction and reperfusion injury. Cardiovascular research. 2012;94:359–369. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chambers KT, Leone TC, Sambandam N, Kovacs A, Wagg CS, Lopaschuk GD, Finck BN, Kelly DP. Chronic inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase in heart triggers an adaptive metabolic response. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:11155–11162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.217349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeoung NH, Harris RA. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 deficiency lowers blood glucose and improves glucose tolerance in diet-induced obese mice. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2008;295:E46–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00536.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menegazzo L, Albiero M, Avogaro A, Fadini GP. Endothelial progenitor cells in diabetes mellitus. BioFactors. 2012;38:194–202. doi: 10.1002/biof.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morrison SJ, Scadden DT. The bone marrow niche for haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2014;505:327–334. doi: 10.1038/nature12984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Schoors S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Cantelmo AR, Quaegebeur A, Ghesquiere B, Cauwenberghs S, Eelen G, Phng LK, Betz I, Tembuyser B, Brepoels K, Welti J, Geudens I, Segura I, Cruys B, Bifari F, Decimo I, Blanco R, Wyns S, Vangindertael J, Rocha S, Collins RT, Munck S, Daelemans D, Imamura H, Devlieger R, Rider M, Van Veldhoven PP, Schuit F, Bartrons R, Hofkens J, Fraisl P, Telang S, Deberardinis RJ, Schoonjans L, Vinckier S, Chesney J, Gerhardt H, Dewerchin M, Carmeliet P. Role of pfkfb3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell. 2013;154:651–663. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teslaa T, Teitell MA. Pluripotent stem cell energy metabolism: An update. The EMBO journal. 2015;34:138–153. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Field SJ, Tsai FY, Kuo F, Zubiaga AM, Kaelin WG, Jr, Livingston DM, Orkin SH, Greenberg ME. E2f-1 functions in mice to promote apoptosis and suppress proliferation. Cell. 1996;85:549–561. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou J, Cheng M, Wu M, Boriboun C, Jujo K, Xu S, Zhao TC, Tang YL, Kishore R, Qin G. Contrasting roles of e2f2 and e2f3 in endothelial cell growth and ischemic angiogenesis. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2013;60:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee KK, Workman JL. Histone acetyltransferase complexes: One size doesn’t fit all. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2007;8:284–295. doi: 10.1038/nrm2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu C, Thompson CB. Metabolic regulation of epigenetics. Cell metabolism. 2012;16:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wellen KE, Hatzivassiliou G, Sachdeva UM, Bui TV, Cross JR, Thompson CB. Atp-citrate lyase links cellular metabolism to histone acetylation. Science. 2009;324:1076–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1164097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tormos KV, Anso E, Hamanaka RB, Eisenbart J, Joseph J, Kalyanaraman B, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial complex iii ros regulate adipocyte differentiation. Cell metabolism. 2011;14:537–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teixeira FK, Sanchez CG, Hurd TR, Seifert JR, Czech B, Preall JB, Hannon GJ, Lehmann R. Atp synthase promotes germ cell differentiation independent of oxidative phosphorylation. Nature cell biology. 2015;17:689–696. doi: 10.1038/ncb3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.