SUMMARY

Objective

To compare the effectiveness of physical therapy (PT, evidence-based approach) and internet-based exercise training (IBET), each vs a wait list (WL) control, among individuals with knee osteoarthritis (OA).

Design

Randomized controlled trial of 350 participants with symptomatic knee OA, allocated to standard PT, IBET and WL control in a 2:2:1 ratio, respectively. The PT group received up to eight individual visits within 4 months. The IBET program provided tailored exercises, video demonstrations, and guidance on progression. The primary outcome was the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC, range 0 [no problems]–96 [extreme problems]), assessed at baseline, 4 months (primary time point) and 12 months. General linear mixed effects modeling compared changes in WOMAC among study groups, with superiority hypotheses testing differences between each intervention group and WL and non-inferiority hypotheses comparing IBET with PT.

Results

At 4-months, improvements in WOMAC score did not differ significantly for either the IBET or PT group compared with WL (IBET: −2.70, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = −6.24, 0.85, P = 0.14; PT: −3.36, 95% (CI) = −6.84, 0.12, P = 0.06). Similarly, at 12-months mean differences compared to WL were not statistically significant for either group (IBET: −2.63, 95% CI = −6.37, 1.11, P = 0.17; PT: −1.59, 95% CI = −5.26, 2.08, P = 0.39). IBET was non-inferior to PT at both time points.

Conclusions

Improvements in WOMAC score following IBET and PT did not differ significantly from the WL group. Additional research is needed to examine strategies for maximizing benefits of exercise-based interventions for patients with knee OA.

Trial registration

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Knee, Physical therapy, Internet, Physical activity

Introduction

Exercise is a recommended component of treatment for knee osteoarthritis (OA), based on studies showing improvements in pain, function and other outcomes1–3. However, the majority of adults with OA are inactive, highlighting the continued need for increasing regular engagement in exercise4,5. Physical therapists can play a key role in instructing patients with OA in an appropriate exercise program (as well as deliver other treatments such as orthotics, braces, gait aids and manual therapy), and physical therapy (PT) care is a recommended, evidence-based component of knee OA treatment2,6. However, PT is underutilized for knee OA7–9, partly due to health care access-related issues, particularly for uninsured and under-insured patients and those in medically underserved areas. Individuals with lower socioeconomic status likely have the least access to a physical therapist or a supervised exercise program, yet these individuals also bear a greater burden of OA10,11.

Internet-based programs are an alternative, low-cost method for providing instruction and support in appropriate exercise. However, there has been little research on internet-based exercise programs for patients with OA12–15 or older adults16,17. Further, there have been no direct comparisons of internet-based exercise programs with supervised exercise-based therapies for knee OA. This study compared the effectiveness of an internet-based exercise training (IBET) program to in-person PT among individuals with symptomatic knee OA. Specifically, this study tested whether PT or IBET were superior to a wait list (WL) control group at 4-month (primary time point) and 12-month follow-up. Additionally, analyses examined whether IBET was non-inferior to PT.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) and Duke University Medical Center. Detailed methods have been published18. Recruitment occurred from November 2014 to February 2016, and follow-up assessments were completed in February 2017.

Study design

The PT vs IBET for Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis (PATH-IN) study was a pragmatic randomized controlled trial with participants assigned to standard PT, IBET and WL control, with allocation of 2:2:1, respectively. Randomization schedules were computer generated by a statistician with stratification by recruitment source (UNC Healthcare system, Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project19 and self-referral). Participants continued with usual medical care for OA. Participants in the WL group did not receive PT or IBET during the study but were offered two PT visits and access to IBET following 12-month assessments.

Participants and recruitment

Study inclusion criteria were: (1) Radiographic evidence of knee OA, physician diagnosis of knee OA in the medical record, or self-report of physician diagnosis along with items based on the American College of Rheumatology clinical criteria20. (2) Self-report of pain, aching or stiffness in one or both knees on most days of the week. Exclusion criteria are shown in Box 1. Participants were recruited using two methods: (1) Active recruitment of patients with evidence of knee OA in the UNC medical record, as well as participants with knee OA in the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project19; these individuals were mailed an introductory letter, with telephone follow-up. (2) Advertisement within UNC and the surrounding communities. All individuals who met eligibility criteria based on telephone-based screening completed consent and baseline assessments in person. Participants were then given their randomization assignment via telephone by the study coordinator.

Box 1. Exclusion Criteria.

No regular internet access

Currently meeting Department of Health and Human Services Guidelines for physical activity

Currently completing series of PT visits for knee OA

Diagnosis of gout in the knee, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, or other systemic rheumatic disease

Severe dementia or other memory loss condition

Active diagnosis of psychosis or current uncontrolled substance abuse disorder

On waiting list for arthroplasty

Hospitalization for a stroke, heart attack, heart failure, or had surgery for blocked arteries in the past 3 months

Total joint replacement knee surgery, other knee surgery, meniscus tear, or ACL tear in the past 6 months

Severely impaired hearing or speech

Unable to speak English

Serious or terminal illness as indicated by referral to hospice or palliative care

Other health problem that would prohibit participation in the study

Nursing home residence

Current participation in another OA intervention

Fall history deemed by a study physical therapist co-investigator to impose risk for potential injury with participation in a home-based exercise program study

IBET program

The IBET program was developed by Visual Health Information and a multidisciplinary team, including physical therapists, physicians and patients; details have been described14. Features of the IBET program include: (1) Tailored Exercises based on measures regarding pain, function and current activity, along with an algorithm that assigns participants to one of seven different exercise levels. Exercise routines include strengthening, stretching and aerobic activity recommendations. (2) Exercise Progression recommendations, based on serial measures of pain and function. (3) Video Display of Exercises (and photographs) to demonstrate proper exercise performance. (4) Automated Reminders to engage with the website and remain active if participants have not logged in for 7 days. (5) Progress Tracking, including graphs of pain, function, and exercise over time. Participants were asked to access the IBET site as soon as they were randomized and to continue through the 12-month follow-up assessment. In accordance with current Department of Health and Human Services and other guidelines for physical activity21, participants were encouraged to complete strengthening and stretching exercises at least 3 times per week and to engage in aerobic exercises daily, or as often as possible.

Physical therapists (with experience in treating OA) at multiple clinics administered the intervention following training by PT co-investigators (YMG, APG), who also performed periodic fidelity checks. The PT intervention, described in detail elsewhere18, was modeled after recommended elements of care provided to patients with knee OA22, including: (1) evaluation of strength, flexibility, mobility, balance, function, knee alignment, and possible limb length inequality; (2) evaluation of the need for assistive devices, knee braces, patellar taping, heel lifts, shoe wedges and other footwear modifications; (3) instruction in an appropriate home exercise program (including strengthening, stretching/range of motion, and aerobic exercises); (4) instruction in activity pacing and joint protection; (5) manual therapy, if appropriate; (6) modalities for pain management, if appropriate. Emphasis was placed on the home exercise program, which was initiated at the first visit. To mirror standard clinical practice, physical therapists were permitted to tailor visits to patients' needs and functional limitations. Based on a typical range of outpatient PT visits for knee OA, study participants could receive up to eight one-hour sessions. At the first visit, physical therapists completed a standardized evaluation form and documented treatment provided. At subsequent visits, physical therapists completed progress notes including documentation of treatment provided. The Appendix lists the guidance given to physical therapists.

Measures

Baseline, 4-month and 12-month assessments were conducted by trained research assistants blinded (via database restrictions) to participants' randomization assignment. Assessments were typically conducted in person, though telephone-based follow-up assessments were permitted in cases where participants are unable to return to the study site. Participants were paid $30 for completion of assessments at each time point.

Primary outcome: Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) total score

The WOMAC is a measure of lower extremity pain (five items), stiffness (two items), and function (17 items)23,24. All items were rated on a Likert scale of 0 (no symptoms)–4 (extreme symptoms), with a total range of 0–96 and higher scores indicating worse symptoms.

Secondary outcomes

We examined the WOMAC pain (range 0 [no pain]–20 [extreme pain]) and function (range 0 [no difficulty]−68 [extreme difficulty]) subscales separately. We also conducted four tests of physical function: the 30-second chair stand25, the Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)26,27, a two-minute step test28, and unilateral stand time29,30. The latter was part of the Four-Stage Balance Test30, and participants scored a “0” if they were unable to stand for 10 s in side-by-side, semi-tandem or tandem positions. Self-reported physical activity was assessed with the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE), which measures occupational, household, and leisure activities during a 1-week period; the typical range for the total PASE score is 0–400, with higher scores indicating greater activity31. In addition, participants self-reported their current minutes per week of stretching, strengthening and aerobic exercise. Participants' Global Assessment of Change in right and left knee (separately) pain, aching and stiffness was reported at follow-up assessments. This scale ranged from −6 (a very great deal worse) to +6 (a very great deal better); data were coded as missing if participants never had symptoms in that knee or responded “don't know.”

Intervention delivery

We report the number of days on which participants in the IBET group logged into the website and the number of PT visits attended. For each participant in the PT group we calculated the proportion of visits at which the therapist reported delivering specific interventions.

Non-study PT visits

At 4-month and 12-month follow-up, we asked participants whether they received PT care for knee OA outside the study since their last visit. This informed per-protocol analyses described below.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Self-reported participant characteristics included age, race/ ethnicity, gender, household financial state (with low income defined as self-report of “just meeting basic expenses” or “don't even have enough to meet basic expenses”), education level (bachelor's degree vs less education), work status (employed vs not working), marital status, joints affected by OA, duration of OA symptoms, self-rated health (excellent, very good or good vs fair or poor), and depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-8)32. Height and weight were measured at baseline to calculate body mass index (BMI). Participants also self-reported use of other OA treatments at both follow-up time points, including pain medication use, knee injections, knee brace use, and topical creams.

Adverse event assessment

Adverse events were identified through regular reports of participants' visits to the UNC healthcare system, as well as through participants' reports to study team members.

Sample size

As detailed elsewhere1, the sample size estimate of N = 350 was based on the hypothesis of non-inferiority, which is the most conservative33–35, and on the 2:2:1 randomization ratio36. A one-sided, two-sample t test sample size calculation was used at the 0.025 significance level for the difference in mean WOMAC between IBET and PT to be less than five points at 4-month follow-up, with an adjustment to the variance to account for repeated measures37 and potential 10% attrition.

Data analyses

We tested four hypotheses: H1: Participants who receive either IBET or standard PT will have clinically relevant improvements in WOMAC at 4-month follow-up, compared with WL control group. H2: IBET will be non-inferior to PT (an intervention with established evidence6) at 4-month follow-up, indicated by a mean WOMAC score less than five points higher (worse) than PT. For total WOMAC scores, a five point non-inferiority margin was selected because it is on the border of what would be considered a clinically important effect in this context38,39. H3 and H4 mirrored H1 and H2 but at the 12-month follow-up time point. For the superiority hypotheses (H1, H3), primary conclusions were based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses, with participants assigned to the arm to which they were randomized, regardless of adherence, using all available follow-up data40. For non-inferiority hypotheses (H2, H4), the ITT analysis would not necessarily be the conservative approach41. We therefore performed analyses on both an ITT and per-protocol basis35,42. For the latter we excluded individuals who did not adhere to their assigned study group, including those in the PT group (N = 9) who attended no visits, those in the IBET group who did not log on to the website (N = 28), and those in the IBET (N = 5) and WL (N = 4) groups who received PT outside the study.

A general linear mixed effects model was fitted with changes from baseline in WOMAC scores as the dependent variables with an unstructured covariance matrix to account for the two follow-up repeated measures. Fixed effects included follow-up time, intervention group, their interaction, baseline WOMAC score, and enrollment source. The SAS MIXED procedure (Cary, NC) was used to fit these models and to test linear contrasts corresponding to each hypothesis. Participants missing either follow-up measurement were still included in the model under a ‘missing at random' paradigm. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted through multiple imputation of missing values (see below).

To test the null hypothesis of non-inferiority of IBET vs standard PT at 4 months in management of OA symptoms, the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the appropriate linear contrast was constructed; non-inferiority was concluded if the upper limit of the interval was less than the non-inferiority margin of five points42. Superiority hypotheses involved two comparisons vs WL control, so each was conducted at the two-sided 0.025 significance level. The non-inferiority hypotheses involve only one comparison and were tested at the full one-sided 0.025 significance level.

We had several strategies for handling missing data. When individual items were missing from self-report scales, we followed guidelines regarding when to impute scores43. When guidelines were unavailable, we treated the scale as missing if > 1 item was missing; when one item was missing we substituted with the mean of available items. When participants declined or could not complete function tests they were assigned the lowest value for that test; when participants ran out of time to complete function tests or assessments were completed via telephone, data were treated as missing. In some cases (four at 4-months, five at 12-months), our data coding scheme did not allow us to differentiate between these two situations; these were treated as missing. For sensitivity analysis for the ITT approach, we performed multiple imputation to deal with missing data at follow-up assessments via the SAS MI and MIANALYZE procedures, specifying 30 imputations. First, three missing race values were imputed based on other participant characteristics. Then we identified baseline characteristics that differed between completers and non-completers at follow-up at the P ≤ 0.25 level. These characteristics were used to impute missing baseline WOMAC values. Next, missing 4-month WOMAC scores were imputed as a function of these baseline characteristics, baseline WOMAC score, and treatment group; imputation of 12-month WOMAC score also included 4-month WOMAC scores. The same imputation process was followed for secondary outcomes.

Corresponding analytic strategies were used for secondary outcomes, though there was insufficient information in the literature to define a non-inferiority margin for these measures. Additionally, as the Global Assessment of Change variables do not have baseline values, the actual values (rather than change from baseline) were managed as the response variable, with no baseline score as a covariate. A square root transformation was used for the weekly minutes of exercise variables to improve the residuals with respect to the normality assumption. To provide comparison with prior studies, we calculated standardized mean differences (SMDs) for WOMAC total and subscale scores for both intervention groups compared to WL (ratio of model-predicted mean group differences to their pooled standard deviation (SD)).

Results

Participants and retention

We identified 11,274 potential participants from all recruitment sources (Fig. 1). Of 683 who completed telephone screening, 350 (51%) were eligible, enrolled and randomized. Because randomization was stratified by enrollment source, allocation across groups was slightly different than the 2:2:1 ratio, with 142 participants assigned to the IBET group, 140 to the PT group and 68 to the WL group. At both 4-month and 12-month follow-up, 86% of participants completed primary outcomes (Fig. 1). Compared with participants who completed follow-up assessments for the primary outcome at 12-months, non-completers had a higher baseline mean WOMAC total score (31.2, SD = 17.6 vs 37.6, SD = 19.1, respectively). Participant characteristics are shown in Table I. Participants' use of other OA treatments at follow-up was similar across groups (Appendix Table I).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram.

Table I.

Participant characteristics at baseline*

| Characteristic | All participants (N = 350) | IBET group (N = 142) | PT group (N = 140) | WL control (N = 68) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.3 (11.1) | 65.3 (11.5) | 65.7 (10.3) | 64.3 (12.2) |

| Women N (%) | 251 (71.7%) | 98 (69%) | 100 (71.4%) | 53 (77.9%) |

| Non-white race N (%) | 95 (27.4%) | 48 (33.8%) | 29 (21%) | 18 (26.9%) |

| Married or living with partner N (%) | 215 (61.4%) | 93 (65.5%) | 80 (57.1%) | 42 (61.8%) |

| Bachelors degree N (%) | 208 (59.4%) | 80 (56.3%) | 86 (61.4%) | 42 (61.8%) |

| Employed N (%) | 141 (40.3%) | 51 (35.9%) | 59 (42.1%) | 31 (45.6%) |

| Household financial status: low income N (%) | 62 (17.8%) | 29 (20.6%) | 20 (14.3%) | 13 (19.1%) |

| Fair or poor health N (%) | 48 (13.7%) | 22 (15.5%) | 14 (10%) | 12 (17.6%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 31.4 (8) | 31.5 (7.8) | 31.9 (8.6) | 30.1 (7.3) |

| Joints with OA symptoms | 5.4 (3.2) | 5.2 (3.1) | 5.5 (3) | 5.5 (3.9) |

| Duration of OA symptoms, years | 13.1 (11.7) | 11.6 (11) | 14.1 (11.6) | 14.2 (13) |

| PHQ-8 score | 3.8 (4.1) | 3.7 (4.1) | 4 (4.5) | 3.6 (3.5) |

| WOMAC total | 32.0 (17.9) | 31.3 (17.5) | 32 (17.7) | 33.6 (19.2) |

| WOMAC pain subscale | 6.1 (3.8) | 6.0 (3.9) | 6.1 (3.5) | 6.2 (4.0) |

| WOMAC function subscale | 22.5 (13.0) | 21.8 (12.7) | 22.6 (12.9) | 23.9 (13.8) |

| PASE total score | 126.9 (72.7) | 132.3 (71.2) | 121.4 (72) | 126.9 (77.2) |

| PASE household score | 75.2 (40.7) | 81.6 (41.3) | 70.4 (40.4) | 71.8 (38.8) |

| PASE leisure score | 21.6 (21.9) | 22.4 (21.9) | 20.9 (23.2) | 21.5 (19.7) |

| PASE work score | 30.7 (51.1) | 30.5 (51.5) | 29.1 (48.4) | 34.2 (55.9) |

| Timed Up and Go, seconds | 11.9 (4.3) | 12 (4.6) | 11.9 (4.2) | 11.6 (3.7) |

| Unilateral stand test, seconds | 7.2 (3.6) | 7.3 (3.5) | 7.3 (3.6) | 6.7 (3.7) |

| 30 s chair stand | 9.5 (3.9) | 9.5 (3.8) | 9.5 (4.2) | 9.6 (3.5) |

Missing Data: non-white race = 3, household financial status = 1, WOMAC = 2, Timed Up and Go = 4, PASE total = 10, PASE Household = 5, PASE work = 1, PASE Leisure = 6. PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; PASE = Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

Values are Mean (SD) unless otherwise specified.

Adverse events

There were four non-serious study-related events in the PT group (one fall, three increased knee pain) and four in the IBET group (two increased knee pain, one shoulder pain, one ankle pain).

Intervention delivery

Between baseline and 4-month follow-up, 114 (80%) of participants in the IBET group logged onto the website; the mean (SD) number of days logged on was 20.7 (24.6), median = 9.5. Between baseline and 12-month follow-up, 115 (81%) of participants in the IBET group logged onto the website with a mean (SD) number of days logged on of 40.5 (59.8) median = 10.5. The mean number of days logged onto the website between 4-month and 12-month follow-up was 19.8 (37.7), median = 0. Seven physical therapists contributed to intervention delivery, with numbers of participants treated by each PT ranging from 2 to 40; this wide range was primarily due to participants' geographic proximity to the different study PT clinics. Among participants in the PT group, 131 (94%) attended at least one visit; 51% attended 6–8 visits. The mean (SD) number of visits was 5.7 (2.5), with a median of 7.0 visits. The mean proportions of visits per patient at which therapists reported delivering specific intervention components were: Therapeutic Exercise – 94%; Balance/Neuromuscular Education – 38%; Manual Therapy – 43%; Gait/Strength Training – 44%; Modalities – 29%; and Shoes/Wedges – 20%.

Primary outcome: WOMAC total score

ITT analyses

Superiority hypotheses

Neither IBET nor PT were superior to WL at 4 months or 12 months at the specified P < 0.025 (Table II, Fig. 2). Multiple imputation analyses showed similar results for both interventions (Appendix Table II). At 4-months, the SMDs for PT and IBET group, respectively were −0.26 (−0.53, 0.00) and −0.20 (−0.48, 0.07), compared to the WL group (Table III). At 12-months, the SMDs for PT and IBET group, respectively were −0.12 (−0.40, 0.16) and −0.19 (−0.46, 0.09), compared to the WL group.

Table II.

Within- and between-group mean changes in outcomes and 95% CIs: Results of ITT analyses

| Outcome | Baseline to 4-month difference (95% CI) | Difference in baseline to 4-month vs WL (95% CI), P-value | Baseline to 12-month difference (95% CI) | Difference in baseline to 12-month vs WL (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMAC total (N = 348)* | ||||

| WL | −3.37 (−6.33, −0.41) | – | −2.83 (−5.93, 0.27) | – |

| PT | −6.73 (−8.86, −4.6) | −3.36 (−6.84, 0.12), 0.06 | −4.42 (−6.66, −2.17) | −1.59 (−5.26, 2.08), 0.39 |

| IBET | −6.06 (−8.29, −3.84) | −2.70 (−6.24, 0.85), 0.14 | −5.46 (−7.82, −3.09) | −2.63 (−6.37, 1.11), 0.17 |

| WOMAC function (N = 348) | ||||

| WL | −2.3 (−4.46, −0.14) | – | −1.51 (−3.76, 0.74) | – |

| PT | −4.77 (−6.32, −3.23) | −2.48 (−5.02, 0.07), 0.06 | −3.3 (−4.91, −1.68) | −1.79 (−4.45, 0.87), 0.19 |

| IBET | −3.74 (−5.36, −2.12) | −1.44 (−4.03, 1.15), 0.27 | −3.4 (−5.11, −1.7) | −1.90 (−4.61, 0.82), 0.17 |

| WOMAC pain (N = 350) | ||||

| WL | −0.66 (−1.41, 0.09) | – | −0.64 (−1.38, 0.09) | – |

| PT | −1.11 (−1.65, −0.58) | −0.45 (−1.33, 0.42), 0.31 | −0.7 (−1.23, −0.16) | −0.05 (−0.92, 0.81), 0.90 |

| IBET | −1.59 (−2.15, −1.02) | −0.93 (−1.82, −0.03), 0.04 | −1.15 (−1.71, −0.59) | −0.51 (−1.39, 0.38), 0.26 |

| PASE total (N = 340) | ||||

| WL | −4.7 (−21.04, 11.64) | – | 1.17 (−13.11, 15.45) | – |

| PT | 2.25 (−9.18, 13.68) | 6.95 (−12.31, 26.22) , 0.48 | 8.28 (−2.01, 18.56) | 7.11 (−9.69, 23.91), 0.41 |

| IBET | −11.52 (−23.79, 0.74) | −6.82 (−26.55, 12.91), 0.50 | 8.19 (−2.99, 19.37) | 7.02 (−10.31, 24.35), 0.43 |

| PASE leisure (N = 344) | ||||

| WL | −2.41 (−7.49, 2.66) | – | −0.11 (−6.25, 6.04) | – |

| PT | 3.27 (−0.28, 6.82) | 5.68 (−0.25, 11.62), 0.06 | 8.68 (4.3, 13.05) | 8.78 (1.46, 16.1), 0.02 |

| IBET | −1.34 (−5.14, 2.46) | 1.07 (−5.70, 0.14), 0.73 | 7.66 (2.94, 12.39) | 7.77 (0.25, 15.29), 0.04 |

| PASE household (N = 345) | ||||

| WL | −5.32 (−14.49, 3.84) | – | −3.42 (−11.59, 4.75) | – |

| PT | −1.07 (−7.50, 5.36) | 4.25 (−6.59, 15.09), 0.44 | 2.3 (−3.61, 8.21) | 5.72 (−3.94, 15.38), 0.25 |

| IBET | −9.16 (−16.11, −2.21) | −3.84 (−14.99, 7.31), 0.50 | −3.72 (−10.13, 2.69) | −0.3 (−10.26, 9.67), 0.95 |

| PASE Work (N = 349) | ||||

| WL | 2.35 (−8.45, 13.15) | – | 5.24 (−4.49, 14.98) | – |

| PT | 0.98 (−6.53, 8.48) | −1.37 (−14.12, 11.37), 0.83 | −2.62 (−9.58, 4.34) | −7.86 (−19.36, 3.63), 0.18 |

| IBET | −2.00 (−10.01, 6) | −4.35 (−17.39, 8.69), 0.51 | 5.25 (−2.2, 12.69) | 0.00 (−11.78, 11.79), 1.00 |

| Unilateral stand time (N = 350) | ||||

| WL | 0.04 (−0.75, 0.82) | – | −0.09 (−0.88, 0.69) | – |

| PT | −0.59 (−1.15, −0.03) | −0.63 (−1.56, 0.30), 0.19 | −0.05 (−0.6, 0.50) | 0.04 (−0.89, 0.98), 0.93 |

| IBET | 0.02 (−0.57, 0.61) | −0.02 (−0.97, 0.93), 0.97 | −0.05 (−0.64, 0.53) | 0.04 (−0.91, 1.00), 0.93 |

| 30 s chair stand (N = 350) | ||||

| WL | 0.18 (−0.87, 1.23) | – | 0.66 (−0.27, 1.58) | – |

| PT | −0.13 (−0.87, 0.61) | −0.31 (−1.55, 0.94), 0.63 | 0.16 (−0.49, 0.82) | −0.49 (−1.58, 0.60), 0.37 |

| IBET | 0.50 (−0.29, 1.28) | 0.32 (−0.95, 1.59), 0.62 | 0.90 (0.20, 1.60) | 0.24 (−0.87, 1.35), 0.67 |

| 2 m march test (N = 350) | ||||

| WL | −8.43 (−14.61, −2.24) | – | 0.00 (−6.49, 6.48) | – |

| PT | −0.68 (−5.07, 3.71) | 7.75 (0.43, 15.07), 0.04 | 1.11 (−3.45, 5.67) | 1.12 (−6.59, 8.82), 0.78 |

| IBET | −3.54 (−8.20, 1.11) | 4.88 (−2.56, 12.33), 0.20 | 1.12 (−3.76, 6) | 1.13 (−6.74, 8.99), 0.78 |

| Timed Up and Go (N = 346) | ||||

| WL | −0.23 (−1.24, 0.78) | – | −0.26 (−1.4, 0.87) | – |

| PT | −0.62 (−1.34, 0.09) | −0.39 (−1.58, 0.8), 0.52 | −0.77 (−1.57, 0.04) | −0.5 (−1.86, 0.85), 0.46 |

| IBET | −0.87 (−1.63, −0.11) | − −0.64 (−1.85, 0.58), 0.30 | −1.49 (−2.35, −0.63) | −1.22 (−2.61, 0.16), 0.08 |

| Weekly minutes of aerobic activity** | ||||

| WL | −0.09 (−1.53, 1.35) | – | −1.59 (−3.21, 0.04) | – |

| PT | 1 (−0.02, 2.02) | 1.09 (−0.61, 2.8), 0.21 | 0.48 (−0.67, 1.63) | 2.07 (0.13, 4), 0.04 |

| IBET | 1.79 (0.71, 2.88) | 1.89 (0.15, 3.62), 0.03 | 0.41 (−0.82, 1.63) | 1.99 (0.01, 3.97), 0.05 |

| Weekly minutes of stretching** | ||||

| WL | −0.4 (−1.39, 0.6) | – | −1.34 (−2.24, −0.44) | – |

| PT | 1.45 (0.76, 2.15) | 1.85 (0.67, 3.03), 0.00 | 0.27 (−0.37, 0.92) | 1.62 (0.55, 2.68), 0.00 |

| IBET | 0.97 (0.23, 1.72) | 1.37 (0.16, 2.57), 0.03 | 0.72 (0.04, 1.41) | 2.07 (0.98, 3.16), 0.00 |

| Weekly minutes of strengthening** | ||||

| WL | 0.43 (−0.69, 1.54) | – | −0.14 (−1.32, 1.04) | – |

| PT | 1.78 (0.99, 2.57) | 1.36 (0.05, 2.66), 0.04 | 1.07 (0.23, 1.91) | 1.21 (−0.18, 2.6), 0.09 |

| IBET | 1.27 (0.44, 2.11) | 0.85 (−0.49, 2.19), 0.22 | 1.21 (0.32, 2.1) | 1.35 (−0.08, 2.78), 0.06 |

| Patient global assessment of change – right Knee | ||||

| WL | 0.15 (−0.36, 0.66) | – | −0.18 (−0.69, 0.33) | – |

| PT | 1.36 (0.99, 1.73) | 1.21 (0.6, 1.81), 0.00 | 0.58 (0.2, 0.96) | 0.76 (0.15, 1.37), 0.01 |

| IBET | 0.42 (0.03, 0.82) | 0.27 (−0.35, 0.89), 0.39 | 0.53 (0.12, 0.94) | 0.71 (0.08, 1.33), 0.03 |

| Patient global assessment of change – left Knee | ||||

| WL | −0.09 (−0.64, 0.45) | – | −0.38 (−0.95, 0.19) | – |

| PT | 0.93 (0.56, 1.31) | 1.03 (0.39, 1.66), 0.00 | 0.17 (−0.24, 0.59) | 0.56 (−0.12, 1.23), 0.11 |

| IBET | 0.46 (0.06, 0.86) | 0.56 (−0.1, 1.21), 0.09 | 0.57 (0.13, 1.01) | 0.95 (0.26, 1.64), 0.01 |

Notes: Between-group comparisons refer to changes from baseline for each intervention group relative to the WL group. Results are least-squares means and mean differences (and corresponding 95% CIs) from separate general linear mixed effects models, as described in the Methods.

WOMAC = Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; PASE = Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly.

Indicates number included in the statistical model for that outcome.

A square root transformation was applied due to superior diagnostics in statistical models.

Fig. 2.

Estimated mean WOMAC Total Scores and 95% CIs by Group and Time Point.

Table III.

SMDs and 95% CIs for IBET and PT vs WL control group

| Outcome | 4 Months | 12 Months |

|---|---|---|

| WOMAC total | ||

| lPT | −0.26 (−0.53, 0.00) | −0.12 (−0.40, 0.16) |

| IBET | −0.20 (−0.48, 0.07) | −0.19 (−0.46, 0.09) |

| WOMAC function | ||

| PT | −0.27 (−0.52, −0.01) | −0.19 (−0.45, 0.08) |

| IBET | −0.15 (−0.43, 0.13) | −0.19 (−0.45, 0.08) |

| WOMAC pain | ||

| PT | −0.14 (−0.39, 0.11) | −0.02 (−0.31, 0.27) |

| IBET | −0.28 (−0.41, −0.15) | −0.15 (−0.39, 0.09) |

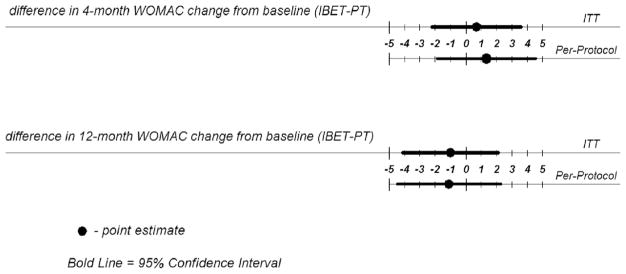

Non-inferiority hypotheses

Compared to PT, IBET effects were within the pre-specified non-inferiority limit of five points on the WOMAC total score at both 4-months (estimate = 0.67, 95% CI = −2.23, 3.56; P = 0.65) and 12-months (estimate = −1.04, 95% CI = −5.26, 2.08; P = 0.39), Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of change in WOMAC total scores between IBET and PT group (non-inferiority hypotheses): Results of intent-to-treat analyses.

Per-protocol analyses

Per-protocol analyses yielded similar results (Appendix Table III): The greatest difference was between PT and WL at 4 months (−3.65, 95% CI = −7.34, −0.03, P = 0.05). Differences between IBET and PT were within the pre-specified non-inferiority limit at both time points.

Secondary outcomes

WOMAC subscales

In ITT analyses, changes in WOMAC pain and function did not differ significantly between either intervention group and WL at 4 or 12 months (Table II). There were also no statistically significant differences between PT and IBET (Appendix Table IV). Results were similar in multiple imputation and per-protocol analyses for both WOMAC subscales (Appendix Tables II and III). Table III shows SMDs for both interventions compared to WL.

PASE and weekly minutes of exercise

At 4 months there were no significant differences in PASE sub-scale scores across groups (Table II). At 12 months the PT group had significantly greater improvement in PASE Leisure subscale score compared to WL (P = 0.02). There were no notable differences in multiple imputation or per-protocol analyses of PASE scores (Appendix Tables II and III). There were no significant differences in weekly minutes of strengthening or aerobic exercise across groups at either time point (Table II). The PT group reported greater weekly minutes of stretching than WL at both 4 and 12 months, and the IBET reported greater minutes than WL at 12 months. Results were similar in multiple imputation analyses. In per protocol analyses, the PT group reported greater minutes of strengthening at 4 months and aerobic activity at 12 months compared to WL; the IBET group reported greater minutes of aerobic activity at 4 and 12 months.

Functional tests

For both unilateral stand time and the 30 s chair stand test, there were minimal within-group changes over time and no between-group differences when using ITT (Table II), multiple imputation or per-protocol analyses (Appendix Tables II and III). For the 2-minute march test, the largest difference was between the PT and WL groups at 4 months (ITT estimate = 7.75, 95% CI = 0.43, 15.07, P = 0.04), favoring the PT group; using multiple imputation, this difference was 8.97 (95% CI = 1.68, 16.26, P = 0.02). There were no statistically significant differences in the TUG test for the PT or IBET groups compared to the WL group (Appendix Table II).

Global assessment of knee symptom change

In ITT analyses for the right knee, the PT group reported greater improvement than WL at 4 and 12 months, and the IBET group reported greater improvement than WL at 12 months (Table II). At 4 months, IBET reported less improvement than the PT group. For the left knee, the PT group reported more improvement than WL at 4 months, and the IBET group reported more improvement than WL at 12 months. Results were similar for multiple imputed and per protocol analyses.

Discussion

In this study there were no statistically significant nor clinically meaningful differences in most study outcomes, including total WOMAC score, between intervention groups and the WL group. IBET was non-inferior to PT at both 4 and 12 months for the primary outcome.

Given prior studies on the effectiveness of exercise and PT care for knee OA3,6,44, it is unclear why the PT intervention was not superior to WL for most outcomes. It is challenging to compare effects across PT-based interventions due to heterogeneity in dose (e.g., number and duration of sessions), type and duration. However, a meta-analysis of PT-related interventions for knee OA found that with respect to pain, SMDs were −0.21 (−0.35, −0.08) and −0.69 (−1.24, −0.14) for programs focusing on aerobic and strengthening exercise, respectively6. The SMD for pain immediately following our PT intervention was smaller than these (−0.14) and declined at 12 months. The meta-analysis found that with respect to disability/ function, SMDs were −0.21 (−0.37, −0.04) and −0.16 (−0.48, −0.16), for programs focusing on aerobic and strengthening exercise, respectively. The SMD for function immediately after our PT intervention was somewhat larger than these −(0.27), but declined to 0.19 at 12 months. Therefore, our PT intervention was comparable to pooled estimates of prior PT-related studies regarding function but less effective with respect to pain; overall these effect sizes were small. We aimed for the PT intervention to mirror standard practice, but effects may have been more robust with a greater exercise dose. Recent meta-analyses of OA studies indicate that exercise-based interventions adhering to American College of Sports Medicine dose recommendations resulted in larger improvements44,45. Additional work is needed to develop strategies for standardizing and implementing these recommendations within the structure and limited number of visits typically allowed for routine PT care for knee OA.

Although IBET was non-inferior to PT for most outcomes, these results should be interpreted in light of the small, non-significant effects of the PT intervention. Effect sizes for the IBET intervention were also small. There has been little research on internet-based exercise programs for knee OA, but in two prior studies, effects were somewhat greater than in our study14,15. Both of those prior studies recruited participants via self-referral or opt-in after clinician referral, which may have resulted in more highly motivated samples with greater “readiness to change” compared to our participants, who recruited participants proactively by the study team18. Engagement with the IBET program was relatively low, highlighting the need for strategies to facilitate use of these types of programs and identify patients who may be most likely to benefit.

There are several limitations to our study. First, we did not confirm OA diagnosis with standardized de novo radiographs or independent physician assessments. However, all participants had either a prior radiographic or physician diagnosis of OA (in the medical record or self-reported), so it is very unlikely there were participants without either radiographic or symptomatic OA. Second, self-reported physical activity is often over-reported. However, it is unlikely that this differed among study groups. Third, we did not assess adherence to home exercise. Fourth, because this was a pragmatic study, physical therapists were permitted to vary the intervention in terms of specific exercises assigned and intensity, based on participant needs; this approach has advantages regarding the study of real-world PT practice but presents challenges in evaluating effects of a specific exercise dose. Fifth, this study was conducted in one geographic region and only included participants with regular internet access, which may limit generalizability of findings. Sixth, this sample was relatively well educated, and results may not generalize to patient groups with lower education levels.

In conclusion, in this pragmatic study neither the PT nor IBET intervention resulted in statistically significant or clinically relevant improvement in most outcomes, compared to a WL control group. Effects of both interventions may have been robust if the dose had been greater44,45. In agreement with a recent systematic review46, results of this study suggest additional research is needed to develop strategies for maximizing the effectiveness of PT interventions, including understanding which PT treatments work best for which patients and optimizing intervention dose in the context of real-world clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

Role of the funding

This study was funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute Award (CER-1306-02043). The statements, opinions presented in this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. KDA, LA, LFC, YMG, APG, and TAS receive support from National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Center P60 AR062760. KDA receives support from the Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care, Durham VA Health Care System (CIN 13-410).

The study team thanks all of the study participants, without whom this work would not be possible. We also thank the following team members for their contributions to the research: Caroline Nagle, Kimberlea Grimm, Ashley Gwyn, Bernadette Benas, Alex Gunn, Leah Schrubbe, and Quinn Williams. The study team also expresses gratitude to the Stakeholder Panel for this project: Ms Sandy Walker LPN (Chapel Hill Children's Clinic), Ms Susan Pedersen RN BSN, Ms Sally Langdon Thomas, Mr Ralph B. Brown, Ms Frances Talton CDA RHS Retired, Dr Katrina Donahue, MD, MPH (Department of Family Medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Dr Alison Brooks, MD, MPH (Department of Orthopedics & Rehabilitation at the University of Wisconsin-Madison), Dr Anita Bemis-Dougherty, PT, DPT, MAS (American Physical Therapy Association), Dr Teresa J. Brady, PhD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), Ms Laura Marrow (Arthritis Foundation National Office), Ms Megan Simmons Skidmore (American Institute of Healthcare and Fitness), and Dr Maura Daly Iversen, PT, DPT, SD, MPH, FNAP, FAPTA (Department of Physical Therapy, Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences Northeastern University). The study team thanks study physical therapists and physical therapy assistants: Jennifer Cooke, PT, DPT, Jyotsna Gupta, PT, PhD and Carla Hill, PT, DPT, OCS, Cert MDT (Division of Physical Therapy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Bruce Buley, Andrew Genova, and Ami Pathak (Comprehensive Physical Therapy, Chapel Hill, NC), Chris Gridley and Aaron Kline (Pivot Physical Therapy, Smithfield, NC).

Appendix. Guidance for structure and content of PT visits

Programs, both in the clinic and at home, should be comprehensive and functional, focusing on core and lower body function, but can be tailored to meet the functional abilities, needs and deficits of each participant.

Each visit should emphasize therapeutic exercise and include muscle strengthening, stretching/flexibility/range of motion, and aerobic exercise.

Education on activity pacing, joint protection and pain management.

A home program should be recommended during the first visit and should be progressed over the course of treatment.

-

Home programs should emphasize the following:

-

Strengthening Exercises

Recommend performing strengthening exercises 2–3 times per week

Include functional exercises, such as gait or stair training and neuromuscular education

-

Stretching/flexibility/range of motion Exercises

Recommend performing range of motion exercises daily

-

Aerobic Exercises

Promote “lifestyle” physical activity

Encourage moderate intensity exercise

Episodes of activity should last at least 10 min, if the participant is able

Episodes should be spread out throughout the week with a long-term goal of working up to a total of 150 min of activity per week

Aerobic exercise can be weight-bearing, reduced weight-bearing or non-weight-bearing.

-

Modalities for pain management can be included during the clinic visit and as part of the home program. Modalities should be used conservatively, taking no more than 25% of the time of each clinic visit.

If appropriate, manual therapy and/or patellar taping can be provided during the clinic visit.

Shoes should be assessed during the first visit, and shoe recommendations should be provided, if appropriate.

If limb length inequality or frontal plane knee malalignment is suspected, treatment with shoe lifts or shoe wedges, respectively, should be attempted.

Appendix Table 1.

Proportions of participants reporting use of specific OA treatments by group and follow-up time point

| % of Participants self-reporting use of treatment | IBET | PT | WL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain medications for osteoarthritis | |||

| 4-Month follow-up | 65% | 55% | 60% |

| 12-Month follow-up | 59% | 57% | 52% |

| Knee injection since baseline | |||

| 4-Month follow-up | 7% | 7% | 12% |

| 12-Month Follow-Up | 14% | 12% | 21% |

| PT (non-study) for knee OA since last study visit | |||

| 4-Month follow-up | 5% | 1% | 7% |

| 12-Month follow-up | 12% | 7% | 11% |

| Knee brace (current) | |||

| 4-Month follow-up | 19% | 19% | 20% |

| 12-Month follow-up | 19% | 20% | 17% |

| Topical creams (current) | |||

| 4-Month follow-up | 24% | 23% | 22% |

| 12-Month follow-up | 29% | 28% | 24% |

Appendix Table 2.

Within- and between-group mean changes in outcomes and 95% CIs: Results of ITT analyses with multiple imputation

| Outcome | Baseline to 4-month difference (95% CI) | Difference in baseline to 4-month vs WL (95% CI), P-value | Baseline to 12-month difference (95% CI) | Difference in baseline to 12-month vs WL (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMAC total | ||||

| WL | −3.29 (−6.29, −0.29) | – | −2.95 (−6.04, 0.15) | – |

| PT | −6.85 (−9.01, −4.69) | −3.56 (−7.16, 0.04), 0.05 | −4.72 (−6.96, −2.48) | −1.77 (−5.38, 1.84), 0.34 |

| IBET | −6.00 (−8.19, −3.82) | −2.71 (−6.28, 0.86), 0.14 | −5.68 (−8.03, −3.32) | −2.73 (−6.50, 1.04), 0.16 |

| WOMAC function | ||||

| WL | −2.31 (−4.45, −0.17) | – | −1.63 (−3.95, 0.68) | – |

| PT | −4.97 (−6.50, −3.43) | −2.66 (−5.20, −0.11), 0.04 | −3.39 (−5.04, −1.75) | −1.76 (−4.48, 0.96), 0.21 |

| IBET | −3.97 (−5.57, −2.37) | −1.66 (−4.29, 0.97), 0.22 | −3.75 (−5.41, −2.10) | −2.12 (−4.85, 0.62), 0.13 |

| WOMAC pain | ||||

| WL | −0.65 (−1.4, 0.10) | – | −0.65 (−1.39, 0.09) | – |

| PT | −1.12 (−1.66, −0.58) | −0.47 (−1.36, 0.41), 0.29 | −0.71 (−1.26, −0.17) | −0.06 (−0.94, 0.81), 0.89 |

| IBET | −1.53 (−2.12, −0.95) | −0.89 (−1.8, 0.03), 0.06 | −1.12 (−1.65, −0.58) | −0.47 (−1.33, 0.40), 0.29 |

| PASE total | ||||

| WL | −2.72 (−19.05, 13.61) | – | 1.96 (−12.93, 16.85) | – |

| PT | 2.49 (−9.08, 14.07) | 5.21 (−13.91, 24.33), 0.59 | 7.91 (−2.86, 18.69) | 5.95 (−11.31, 23.22), 0.50 |

| IBET | −11.25 (−24.37, 1.88) | 8.53 (−27.33, 10.26), 0.37 | 9.43 (−2.12, 20.99) | 7.47 (−10.23, 25.18), 0.41 |

| PASE leisure | ||||

| WL | −2.73 (−8.15, 2.69) | – | −0.23 (−6.49, 6.03) | – |

| PT | 4.01 (0.44, 7.58) | 6.74 (0.56, 12.92), 0.03 | 8.81 (4.45, 13.16) | 9.04 (1.67, 16.40), 0.02 |

| IBET | −1.00 (−4.91, 2.91) | 1.74 (−4.59, 8.06), 0.59 | 7.69 (3.09, 12.28) | 7.92 (0.55, 15.29), 0.04 |

| PASE household | ||||

| WL | −5.65 (−14.68, 3.37) | – | −4.05 (−12.07, 3.97) | – |

| PT | −2.05 (−8.34, 4.24) | 3.60 (−7.05, 14.25), 0.51 | 2.02 (−3.85, 7.88) | 6.07 (−3.55, 15.68), 0.22 |

| IBET | −8.83 (−15.61, −2.05) | −3.18 (−14.04, 7.69), 0.57 | −4.12 (−10.69, 2.44) | −0.07 (−10.06, 9.92), 0.99 |

| PASE work | ||||

| WL | 4.38 (−6.81, 15.56) | – | 5.67 (−4.10, 15.44) | – |

| PT | 1.45 (−6.01, 8.91) | −2.93 (−15.79, 9.93), 0.66 | −2.76 (−9.64, 4.11) | −8.43 (−19.85, 2.98), 0.15 |

| IBET | −1.32 (−9.51, 6.87) | −5.70 (−19.48, 8.08), 0.42 | 5.87 (−1.30, 13.04) | 0.20 (−11.46, 11.86), 0.97 |

| Unilateral stand time | ||||

| WL | −0.12 (−0.90, 0.66) | – | −0.14 (−0.94, 0.65) | – |

| PT | −0.53 (−1.08, 0.02) | −0.41 (−1.32, 0.50), 0.38 | −0.02 (−0.55, 0.52) | 0.13 (−0.81, 1.06), 0.79 |

| IBET | 0.08 (−0.53, 0.70) | 0.20 (−0.77, 1.18), 0.68 | 0.02 (−0.54, 0.58) | 0.16 (−0.78, 1.11), 0.73 |

| 30 s chair stand | ||||

| WL | 0.10 (−0.95, 1.16) | – | 0.55 (−0.38, 1.49) | – |

| PT | −0.06 (−0.80, 0.68) | −0.16 (−1.41, 1.09), 0.80 | 0.13 (−0.54, 0.80) | −0.43 (−1.54, 0.69), 0.45 |

| IBET | 0.67 (−0.10, 1.43) | 0.56 (−0.72, 1.85), 0.39 | 0.86 (0.18, 1.55) | 0.31 (−0.84, 1.45), 0.60 |

| 2 m march test | ||||

| WL | −8.83 (−14.99, −2.67) | – | −0.09 (−6.67, 6.50) | – |

| PT | 0.14 (−4.20, 4.48) | 8.97 (1.68, 16.26), 0.02 | 1.06 (−3.68, 5.79) | 1.14 (−6.69, 8.98), 0.77 |

| IBET | −2.38 (−6.88, 2.11) | 6.45 (−0.99, 13.88), 0.09 | 1.35 (−3.51, 6.20) | 1.43 (−6.80, 9.67), 0.73 |

| Timed Up and Go | ||||

| WL | −0.11 (−1.14, 0.91) | – | −0.31 (−1.43, 0.80) | – |

| PT | −0.56 (−1.30, 0.17) | −0.45 (−1.63, 0.73), 0.45 | −0.94 (−1.75, −0.13) | −0.62 (−1.98, 0.73), 0.37 |

| IBET | −0.90 (−1.74, −0.06) | −0.79 (−2.08, 0.50), 0.23 | −1.47 (−2.36, −0.58) | −1.16 (−2.58, 0.27), 0.11 |

| Weekly minutes of aerobic activity* | ||||

| WL | −0.05 (−1.48, 1.38) | – | −1.68 (−3.32, −0.05) | – |

| PT | 0.98 (−0.03, 1.99) | 1.03 (−0.67, 2.73), 0.23 | 0.51 (−0.65, 1.66) | 2.19 (0.24, 4.13), 0.03 |

| IBET | 1.88 (0.76, 3) | 1.93 (0.25, 3.62), 0.02 | 0.49 (−0.77, 1.74) | 2.17 (0.15, 4.18), 0.03 |

| Weekly minutes of stretching* | ||||

| WL | −0.36 (−1.38, 0.65) | – | −1.29 (−2.19, −0.38) | – |

| PT | 1.45 (0.76, 2.15) | 1.81 (0.62, 3), 0.00 | 0.36 (−0.28, 1) | 1.65 (0.58, 2.72), 0.00 |

| IBET | 1.08 (0.31, 1.85) | 1.44 (0.22, 2.67), 0.02 | 0.8 (0.09, 1.51) | 2.09 (1, 3.17), 0.00 |

| Weekly minutes of strengthening* | ||||

| WL | 0.43 (−0.69, 1.55) | – | −0.1 (−1.28, 1.08) | – |

| PT | 1.85 (1.04, 2.65) | 1.42 (0.11, 2.72), 0.03 | 1.17 (0.33, 2.02) | 1.27 (−0.12, 2.67), 0.07 |

| IBET | 1.47 (0.63, 2.32) | 1.04 (−0.31, 2.39), 0.13 | 1.32 (0.38, 2.26) | 1.42 (−0.03, 2.87), 0.05 |

| Patient global assessment of change – right Knee | ||||

| WL | 0.14 (−0.39, 0.67) | – | −0.17 (−0.69, 0.36) | – |

| PT | 1.36 (0.97, 1.74) | 1.22 (0.58, 1.86), 0.00 | 0.60 (0.2, 1.01) | 0.77 (0.14, 1.4), 0.02 |

| IBET | 0.43 (0.04, 0.83) | 0.30 (−0.33, 0.92), 0.35 | 0.53 (0.13, 0.94) | 0.70 (0.04, 1.36), 0.04 |

| Patient global assessment of change – left Knee | ||||

| WL | −0.1 (−0.66, 0.45) | – | −0.39 (−0.96, 0.17) | – |

| PT | 0.94 (0.56, 1.33) | 1.05 (0.4, 1.7), 0.00 | 0.16 (−0.27, 0.59) | 0.55 (−0.14, 1.24), 0.11 |

| IBET | 0.50 (0.1, 0.9) | 0.60 (−0.07, 1.27), 0.08 | 0.58 (0.15, 1.02) | 0.98 (0.28, 1.68), 0.00 |

A square root transformation was applied due to superior diagnostics in statistical models.

Appendix Table 3.

Within- and between-group mean changes in outcomes and 95% CIs: Results of per protocol analyses

| Outcome | Baseline to 4-month difference (95% CI) | Difference in baseline to 4-month vs WL (95% CI), P-value | Baseline to 12-month difference (95% CI) | Difference in baseline to 12-month vs WL (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOMAC total | ||||

| WL | −3.64 (−6.8, −0.48) | – | −2.74 (−6, 0.53) | – |

| PT | −7.29 (−9.56, −5.03) | −3.65 (−7.34, 0.03), 0.05 | −4.71 (−7.07, −2.35) | −1.97 (−5.81, 1.86), 0.31 |

| IBET | −6 (−8.53, −3.46) | −2.36 (−6.23, 1.51), 0.23 | −5.84 (−8.48, −3.19) | −3.1 (−7.13, 0.93), 0.13 |

| WOMAC function | ||||

| WL | −2.48 (−4.79, −0.18) | – | −1.37 (−3.72, 0.97) | – |

| PT | −5.2 (−6.83, −3.56) | −2.71 (−5.4, −0.02), 0.05 | −3.58 (−5.26, −1.9) | −2.21 (−4.96, 0.55), 0.11 |

| IBET | −3.79 (−5.63, −1.95) | −1.31 (−4.13, 1.52), 0.36 | −3.75 (−5.65, −1.86) | −2.38 (−5.27, 0.51), 0.11 |

| WOMAC pain | ||||

| WL | −0.7 (−1.49, 0.09) | – | −0.68 (−1.46, 0.1) | – |

| PT | −1.19 (−1.75, −0.62) | −0.49 (−1.41, 0.43), 0.29 | −0.69 (−1.25, −0.13) | −0.01 (−0.92, 0.9), 0.98 |

| IBET | −1.59 (−2.22, −0.95) | −0.89 (−1.86, 0.08), 0.07 | −1.16 (−1.79, −0.53) | −0.49 (−1.44, 0.47), 0.32 |

| PASE total | ||||

| WL | −2.95 (−20.41, 14.51) | – | 2.36 (−12.43, 17.15) | – |

| PT | 2.39 (−9.73, 14.51) | 5.34 (−15.13, 25.81), 0.61 | 8.33 (−2.3, 18.96) | 5.97 (−11.29, 23.23), 0.50 |

| IBET | −8.85 (−22.92, 5.22) | −5.9 (−27.55, 15.75), 0.59 | 7.94 (−4.41, 20.29) | 5.58 (−12.77, 23.93), 0.55 |

| PASE leisure | ||||

| WL | −2.7 (−8.17, 2.77) | – | −0.79 (−7.26, 5.68) | – |

| PT | 3.39 (−0.42, 7.19) | 6.08 (−0.26, 12.42), 0.06 | 7.93 (3.34, 12.52) | 8.72 (1.07, 16.37), 0.02 |

| IBET | −1.19 (−5.56, 3.18) | 1.51 (−5.18, 8.2), 0.66 | 7.54 (2.24, 12.84) | 8.33 (0.24, 16.42), 0.04 |

| PASE household | ||||

| WL | −3.48 (−13.05, 6.1) | – | −1.79 (−10.37, 6.78) | – |

| PT | −0.57 (−7.24, 6.1) | 2.9 (−8.35, 14.16), 0.61 | 3.4 (−2.78, 9.58) | 5.19 (−4.9, 15.28), 0.31 |

| IBET | −8.55 (−16.33, −0.76) | −5.07 (−17.02, 6.88), 0.40 | −3.1 (−10.25, 4.05) | −1.3 (−12.02, 9.41), 0.81 |

| PASE work | ||||

| WL | 2.27 (−9.4, 13.93) | – | 5.25 (−4.77, 15.26) | – |

| PT | 0.42 (−7.61, 8.46) | −1.84 (−15.53, 11.84), 0.79 | −2.93 (−10.07, 4.21) | −8.18 (−19.91, 3.55), 0.17 |

| IBET | −0.95 (−10.18, 8.28) | −3.22 (−17.64, 11.2), 0.66 | 4.18 (−3.94, 12.3) | −1.07 (−13.41, 11.28), 0.86 |

| Unilateral stand time | ||||

| WL | −0.03 (−0.81, 0.76) | – | −0.21 (−1.04, 0.62) | – |

| PT | −0.6 (−1.15, −0.04) | −0.57 (−1.49, 0.35), 0.22 | −0.09 (−0.66, 0.48) | 0.12 (−0.86, 1.1), 0.80 |

| IBET | 0.19 (−0.43, 0.81) | 0.22 (−0.75, 1.18), 0.66 | 0.01 (−0.65, 0.66) | 0.21 (−0.81, 1.24), 0.68 |

| 30 s chair stand | ||||

| WL | 0.06 (−1.05, 1.17) | – | 0.56 (−0.43, 1.55) | – |

| PT | −0.2 (−0.98, 0.58) | −0.26 (−1.57, 1.05), 0.70 | 0.12 (−0.57, 0.81) | −0.44 (−1.6, 0.71), 0.45 |

| IBET | 0.62 (−0.26, 1.5) | 0.57 (−0.81, 1.94), 0.42 | 0.95 (0.16, 1.73) | 0.38 (−0.83, 1.6), 0.53 |

| 2 m march test | ||||

| WL | −8.51 (−14.94, −2.08) | – | −0.5 (−7.28, 6.28) | – |

| PT | −0.33 (−4.88, 4.22) | 8.18 (0.62, 15.74), 0.03 | 1.73 (−2.94, 6.4) | 2.23 (−5.72, 10.18), 0.58 |

| IBET | −2.32 (−7.42, 2.78) | 6.19 (−1.73, 14.12), 0.12 | 3.01 (−2.33, 8.35) | 3.51 (−4.86, 11.89), 0.41 |

| Timed Up and Go | ||||

| WL | −0.15 (−1.23, 0.93) | – | 0.04 (−1.19, 1.27) | – |

| PT | −0.56 (−1.32, 0.21) | −0.41 (−1.68, 0.86), 0.53 | −0.68 (−1.53, 0.18) | −0.71 (−2.16, 0.73), 0.33 |

| IBET | −0.82 (−1.68, 0.03) | −0.68 (−2, 0.65), 0.32 | −1.56 (−2.53, −0.59) | −1.6 (−3.12, −0.08), 0.04 |

| Weekly minutes of aerobic activity | ||||

| WL | −0.22 (−1.73, 1.29) | – | −1.68 (−3.37, 0) | – |

| PT | 1.11 (0.04, 2.17) | 1.33 (−0.45, 3.1), 0.14 | 0.76 (−0.43, 1.9) | 2.45 (0.45, 4.44), 0.02 |

| IBET | 2.25 (1.04, 3.46) | 2.47 (0.61, 4.33), 0.01 | 0.83 (−0.52, 2.18) | 2.52 (0.42, 4.61), 0.02 |

| Weekly minutes of stretching | ||||

| WL | −0.47 (−1.5, 0.57) | – | −1.37 (−2.32, −0.43) | – |

| PT | 1.61 (0.89, 2.33) | 2.08 (0.87, 3.3), 0.00 | 0.29 (−0.38, 0.97) | 1.67 (0.55, 2.78), 0.00 |

| IBET | 0.84 (0.02, 1.67) | 1.31 (0.03, 2.59), 0.04 | 0.59 (−0.18, 1.36) | 1.96 (0.79, 3.13), 0.00 |

| Weekly minutes of strengthening | ||||

| WL | 0.47 (−0.67, 1.61) | – | −0.17 (−1.4, 1.05) | – |

| PT | 2.02 (1.21, 2.82) | 1.55 (0.22, 2.88), 0.02 | 1.12 (0.25, 2) | 1.3 (−0.15, 2.74), 0.08 |

| IBET | 1.08 (0.17, 1.99) | 0.61 (−0.79, 2.01), 0.39 | 1.19 (0.2, 2.17) | 1.36 (−0.16, 2.88), 0.08 |

| Patient global assessment of change – right knee | ||||

| WL | 0.15 (−0.38, 0.69) | – | −0.2 (−0.74, 0.33) | – |

| PT | 1.43 (1.04, 1.81) | 1.27 (0.64, 1.91), 0.00 | 0.63 (0.24, 1.03) | 0.83 (0.2, 1.47), 0.01 |

| IBET | 0.60 (0.17, 1.03) | 0.45 (−0.21, 1.11), 0.18 | 0.75 (0.29, 1.20) | 0.95 (0.28, 1.62), 0.00 |

| Patient global assessment of change – left knee | ||||

| WL | 0.07 (−0.52, 0.65) | – | −0.33 (−0.92, 0.26) | – |

| PT | 1.03 (0.63, 1.42) | 0.96 (0.28, 1.64), 0.00 | 0.34 (−0.08, 0.77) | 0.67 (−0.03, 1.37), 0.06 |

| IBET | 0.56 (0.11, 1.01) | 0.49 (−0.22, 1.20), 0.17 | 0.82 (0.35, 1.29) | 1.15 (0.43, 1.88), 0.00 |

Appendix Table 4.

Differences in mean changes between IBET and PT and 95% CIs

| Outcome | Difference in baseline to 4-month vs PT (95% CI), P-value | Difference in baseline to 12-month vs PT (95% CI), P-value |

|---|---|---|

| WOMAC total | ||

| ITT | 0.67 (−2.23, 3.56), 0.65 | −1.04 (−4.13, 2.05), 0.51 |

| Multiple Imputation* | 0.85 (−2.06, 3.75), 0.57 | −0.96 (−4.06, 2.14), 0.54 |

| Per Protocol | 1.3 (−1.9, 4.5), 0.43 | −1.13 (−4.49, 2.23), 0.51 |

| WOMAC function | ||

| ITT | 1.04 (−1.07, 3.15), 0.33 | −0.11 (−2.34, 2.13), 0.93 |

| Multiple Imputation | 1.00 (−1.09, 3.08), 0.35 | −0.36 (−2.55, 1.84), 0.75 |

| Per Protocol | 1.41 (−0.92, 3.73), 0.23 | −0.17 (−2.58, 2.23), 0.89 |

| WOMAC pain | ||

| ITT | −0.47 (−1.20, 0.26), 0.20 | −0.45 (−1.18, 0.27), 0.22 |

| Multiple Imputation | −0.41 (−1.16, 0.33), 0.28 | −0.40 (−1.13, 0.32), 0.27 |

| Per Protocol | −0.4 (−1.2, 0.4), 0.33 | −0.47 (−1.27, 0.32), 0.24 |

| PASE total | ||

| ITT | −13.77 (−29.73, 2.19), 0.09 | −0.09 (−14.41, 14.23), 0.99 |

| Multiple Imputation | −13.74 (−29.76, 2.27), 0.09 | 1.52 (−13.12, 16.16), 0.84 |

| Per Protocol | −11.24 (−28.97, 6.49), 0.21 | −0.39 (−15.74, 14.96), 0.96 |

| PASE leisure | ||

| ITT | −4.61 (−9.49, 0.28), 0.06 | −1.01 (−7.20, 5.18), 0.75 |

| Multiple Imputation | −5.00 (−9.98, −0.03), 0.05 | −1.12 (−7.06, 4.82), 0.71 |

| Per Protocol | −4.57 (−10.02, 0.87), 0.09 | −0.39 (−7.12, 6.34), 0.91 |

| PASE household | ||

| ITT | −8.09 (−17.13, 0.94), 0.08 | −6.02 (−14.27, 2.24), 0.15 |

| Multiple Imputation | −6.77 (−15.76, 2.21), 0.14 | −6.14 (−14.69, 2.42), 0.16 |

| Per Protocol | −7.97 (−17.77, 1.82), 0.11 | −6.5 (−15.46, 2.46), 0.15 |

| PASE work | ||

| ITT | −2.98 (−13.45, 7.49), 0.58 | 7.87 (−1.79, 17.53), 0.11 |

| Multiple Imputation | −2.77 (−13.58, 8.04), 0.62 | 8.63 (−0.73, 17.99), 0.07 |

| Per Protocol | −1.38 (−13.1, 10.34), 0.82 | 7.11 (−3.12, 17.34), 0.17 |

| Unilateral stand time | ||

| ITT | 0.61 (−0.16, 1.38), 0.12 | 0.00 (−0.78, 0.77), 1.00 |

| Multiple Imputation | 0.61 (−0.20, 1.43), 0.14 | 0.04 (−0.72, 0.80), 0.92 |

| Per Protocol | 0.79 (−0.01, 1.58), 0.05 | 0.09 (−0.74, 0.92), 0.83 |

| 30 s chair stand | ||

| ITT | 0.63 (−0.40, 1.66), 0.23 | 0.74 (−0.17, 1.64), 0.11 |

| Multiple Imputation | 0.73 (−0.30, 1.75), 0.16 | 0.73 (−0.17, 1.64), 0.11 |

| Per Protocol | 0.82 (−0.3, 1.95), 0.15 | 0.83 (−0.16, 1.82), 0.10 |

| 2 m march test | ||

| ITT | −2.86 (−8.94, 3.21), 0.35 | 0.01 (−6.40, 6.42), 1.00 |

| Multiple Imputation | −2.52 (−8.47, 3.43), 0.41 | 0.29 (−6.34, 6.92), 0.93 |

| Per Protocol | −1.99 (−8.5, 4.52), 0.55 | 1.28 (−5.53, 8.1), 0.71 |

| Timed Up and Go | ||

| ITT | −0.24 (−1.23, 0.74), 0.63 | −0.72 (−1.85, 0.41), 0.21 |

| Multiple Imputation | −0.34 (−1.40, 0.73), 0.53 | −0.53 (−1.69, 0.62), 0.36 |

| Per Protocol | −0.27 (−1.35, 0.82), 0.63 | −0.89 (−2.13, 0.36), 0.16 |

| Weekly minutes of aerobic activity** | ||

| ITT | 0.79 (−0.62, 2.2), 0.27 | −0.07 (−1.69, 1.54), 0.93 |

| Multiple Imputation | 0.9 (−0.57, 2.37), 0.23 | −0.02 (−1.67, 1.63), 0.98 |

| Per Protocol | 1.15 (−0.38, 2.67), 0.14 | 0.07 (−1.66, 1.8), 0.93 |

| Weekly minutes of stretching** | ||

| ITT | −0.48 (−1.46, 0.5), 0.33 | 0.45 (−0.44, 1.34), 0.32 |

| Multiple Imputation | −0.37 (−1.37, 0.63), 0.46 | 0.44 (−0.49, 1.37), 0.35 |

| Per Protocol | −0.77 (−1.82, 0.28), 0.15 | 0.3 (−0.67, 1.27), 0.55 |

| Weekly minutes of strengthening** | ||

| ITT | −0.51 (−1.6, 0.58), 0.36 | 0.14 (−1.03, 1.31), 0.81 |

| Multiple Imputation | −0.38 (−1.47, 0.72), 0.50 | 0.15 (−1.05, 1.34), 0.81 |

| Per Protocol | −0.94 (−2.09, 0.21), 0.11 | 0.07 (−1.19, 1.32), 0.92 |

| Patient global assessment of change – right knee | ||

| ITT | −0.93 (−1.44, −0.42), 0.00 | −0.05 (−0.58, 0.48), 0.85 |

| Multiple Imputation | −0.92 (−1.45, −0.4), 0.00 | −0.07 (−0.6, 0.46), 0.80 |

| Per Protocol | −0.83 (−1.38, −0.28), 0.00 | 0.12 (−0.46, 0.69), 0.69 |

| Patient global assessment of change – left knee | ||

| ITT | −0.47 (−0.99, 0.05), 0.07 | 0.39 (−0.18, 0.97), 0.17 |

| Multiple Imputation | −0.45 (−0.99, 0.09), 0.10 | 0.43 (−0.13, 0.98), 0.13 |

| Per Protocol | −0.47 (−1.04, 0.1), 0.10 | 0.48 (−0.13, 1.08), 0.12 |

Multiple Imputation was performed on missing values under the ITT paradigm.

A square root transformation was applied due to superior diagnostics in statistical models.

Footnotes

Competing interests

Visual Health Information, Inc (VHI) owns the website used in the current manuscript. Heiderscheit and Seversen have received consulting fees from VHI. A patent related to the website described in this manuscript is currently under review.

Authors contributions

KDA, LA, LFC, YMG, APG, BCH, KMH, HS and TAS contributed to the study design and protocol and helped draft the manuscript. HS and BCH contributed to the original design and evaluation of the exercise website. TS and LA contributed to plans for and conduct of statistical analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. YMG and APG oversaw design and fidelity checks for the PT intervention.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2017.12.008.

References

- 1.Meneses SR, Goode AP, Nelson AE, Lin J, Jordan JM, Allen KD, et al. Clinical algorithms to aid osteoarthritis guideline dissemination. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016 Sep;24(9):1487–99. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: the Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;434:701–12. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:1554–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontaine KR, Heo M. Changes in the prevalence of U.S. adults with arthritis who meet physical activity recommendations, 2001–2003. J Clin Rheumatol. 2005;11:13–6. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000152143.25357.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shih VC, Song J, Chang RW, Dunlop DD. Racial differences in activities of daily living limitation onset in older adults with arthritis: a national cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:1521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang SY, Olson-Kellogg B, Shamliyan TA, Choi JY, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Physical therapy interventions for knee pain secondary to osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:632–44. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-9-201211060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhawan A, Mather RC, 3rd, Karas V, Ellman MB, Young BB, Bach BR, Jr, et al. An epidemiologic analysis of clinical practice guidelines for non-arthroplasty treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthroscopy. 2014;30:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cisternas MG, Yelin E, Katz JN, Solomon DH, Wright EA, Losina E. Ambulatory visit utilization in a national, population-based sample of adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1694–703. doi: 10.1002/art.24897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen KD, Bosworth HB, Chatterjee R, Coffman CJ, Corsino L, Jeffreys AS, et al. Clinic variation in recruitment metrics, patient characteristics and treatment use in a randomized clinical trial of osteoarthritis management. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:413. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vavken P, Dorotka R. The burden of musculoskeletal disease and its determination by urbanicity, socioeconomic status, age, and gender - results from 14507 subjects. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1558–64. doi: 10.1002/acr.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackerman IN, Busija L. Access to self-management education, conservative treatment and surgery for arthritis according to socioeconomic status. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2012;26:561–83. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li LC, Lineker S, Cibere J, Crooks VA, Jones CA, Kopec JA, et al. Capitalizing on the teachable moment: osteoarthritis physical activity and exercise net for improving physical activity in early knee osteoarthritis. JMIR Res Protoc. 2013;2:e17. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennell KL, Nelligan R, Dobson F, Rini C, Keefe F, Kasza J, et al. Effectiveness of an internet-delivered exercise and pain-coping skills training intervention for persons with chronic knee pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:453–62. doi: 10.7326/M16-1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks MA, Beaulieu JE, Severson HH, Wille CM, Cooper D, Gau JM, et al. Web-based therapeutic exercise resource center as a treatment for knee osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:158. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bossen D, Veenhof C, Van Beek KE, Spreeuwenberg PM, Dekker J, De Bakker DH. Effectiveness of a web-based physical activity intervention in patients with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e257. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irvine AB, Gelatt VA, Seeley JR, Macfarlane P, Gau JM. Web-based intervention to promote physical activity by sedentary older adults: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:e19. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carr LJ, Dunsiger SI, Lewis B, Ciccolo JT, Hartman S, Bock B, et al. Randomized controlled trial testing an internet physical activity intervention for sedentary adults. Health Psychol. 2013;32:328–36. doi: 10.1037/a0028962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams QI, Gunn AH, Beaulieu JE, Benas BC, Buley B, Callahan LF, et al. Physical therapy vs internet-based exercise training (PATH-IN) for patients with knee osteoarthritis: study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:264. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0725-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jordan JM, Helmick CG, Renner JB, Luta G, Dragomir AD, Woodard J, et al. Prevalence of knee symptoms and radiographic and symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians: the Johnston County Osteoarthritis Project. J Rheumatol. 2007;31:172–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Altman R, Asch D, Bloch G, Bole D, Borenstein K, Brandt K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–49. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertling D, Kessler RM. Knee. In: Hertling D, Kessler RM, editors. Management of Common Musculoskeletal Disorders: Physical Therapy Principles and Methods. 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bellamy N. WOMAC: a 20-year experiential review of a patient-centered self-reported health status questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2473–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones C, RIkli R, Beam WA. 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70:113. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wall JC, Bell C, Campbell S, Davis J. The Timed Get-up-and-Go test revisited: measurement of the component tasks. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2000;37:109–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The Timed up & Go: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.RIkli R, Jones J. Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 1999;7:129–61. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott V, Votova K, Scanlan A, Close J. Multifactorial and functional mobility assessment tools for fall risk among older adults in community, home-support, long-term and acute care settings. Age Ageing. 2007;36:130–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossiter-Fornoff JE, Wolf SL, Wolfson LI, Buchner DM. A cross-sectional validation study of the FICSIT common data base static balance measures. Frailty and injuries: Cooperative studies of intervention techniques. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50:M291–7. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.6.m291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, Janney CA. The physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:153–62. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greene CJ, Morland LA, Durkalski VL, Frueh BC. Noninferiority and equivalence designs: issues and implications for mental health research. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21:433–9. doi: 10.1002/jts.20367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blackwelder WC. “Proving the null hypothesis” in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1982;3:345–53. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(82)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pocock SJ. The pros and cons of noninferiority trials. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2003;17:483–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-8206.2003.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piantadosi S. Clinical Trials: A Methodological Perspective. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borm GF, Fransen J, Lemmens W. A simple sample size formula for analysis of covariance in randomized clinical trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:1234–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angst F, Aeschlimann A, Michel BA, Stucki G. Minimal clinically important rehabilitation effects in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower extremity. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:131–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bellamy N, Hochberg M, Tubach F, Martin-Mola E, Awada H, Bombardier C, et al. Development of multinational definitions of minimal clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptomatic state in osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67:972–80. doi: 10.1002/acr.22538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ICH E9 Expert Working Group. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline - statistical principles for clinical trials. Stat Med. 1999;18:1905–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Snapinn SM. Noninferiority trials. Curr Control Trials Car-diovasc Med. 2000;1:19–21. doi: 10.1186/cvm-1-1-019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Group C. Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 2006;295:1152–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellamy N. WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index User Guide 2002. Version V. Brisbane, Australia: [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartholdy C, Juhl C, Christensen R, Lund H, Zhang W, Henriksen M. The role of muscle strengthening in exercise therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moseng T, Dagfinrud H, Smedslund G, Osteras N. The importance of dose in land-based supervised exercise for people with hip osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25:1563–76. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brasure M, Shamliyan TA, Olson-Kellog B, Butler ME, Kane RL. Physical Therapy for Knee Pain Secondary to Osteoarthritis: Future Research Needs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC048-EF. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]