Abstract

Adolescents with social anxiety disorder (SAD) often present distorted beliefs related to expected social rejection, coupled with avoidance of social stimuli including interpersonal interactions and others' gaze. Social communication (SC) deficits, often seen in SAD, may play a role in avoidance of social stimuli. The present study evaluated whether SC impairment uniquely contributes to diminished or heightened attention to social stimuli. Gaze patterns to social stimuli were examined in a sample of 41 adolescents with SAD (12-16 years of age; 68% female). Unexpectedly, no significant relationship was observed between SC impairment and fixation duration to angry or neutral faces. However, SC impairment did predict greater fixation duration to happy faces, after controlling for social anxiety severity [adjusted R2 = .201, F (2, 38) = 4.536, p = .018]. Clinical implications are discussed, focusing on the potential utility of targeting SC impairments directly in light of the role of SC difficulties in youth with SAD.

Keywords: social communication, social anxiety disorder, adolescents, eye-tracking, visual attention

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) is characterized by irrational and persistent fears of potential evaluation by others [1]. Typically, SAD emerges during adolescence [2] which coincides with heightened interest in developing and maintaining relationships with peers [3,4]. Individuals with SAD, oftentimes, engage in continuous social comparison and are often vigilant to what others may be thinking. Cognitive models of anxiety have affirmed the role of catastrophic (i.e., overestimation of negative outcomes) and distorted beliefs in the maintenance of social anxiety, suggesting that these catastrophic thoughts regarding feared outcomes serve to maintain the phobic anxiety [5, 6]. Avoidance behaviors which are often marked by the evasion of social gaze [7, 8] in individuals with SAD serve to prevent disconfirmation of these distorted beliefs. As currently conceptualized, however, the predictors underlying the developmentally normative increase in social anxiety during adolescence as well as the conditions under which these fears progress into impairment and thus a psychiatric disorder for some adolescents but not others are not well-understood [cf, 9]. Exploration of visual attention to social stimuli in relation to deficits in social communication in youth with SAD may yield insights into social avoidance, including diminished attention to others' gaze, a characteristic of SAD.

Social communication (SC) is an interpersonal process defined by the exchange of information within a social context [10,11]. SC difficulties are characterized by deficits in social behaviors such as engaging in reciprocal conversation and the processing and accurate interpretation of social cues [12]. Although present in various disorders, SC impairments are particularly evident in youth with SAD relative to non-clinical peers [13] as well as youth with other disorders [10, 14]. Impaired social skills, one component of SC impairment, are seen in difficulties with behaviors such as initiating social interactions, asking people to do things, joining in, and refusing unreasonable requests [15]. Social skill deficits among socially anxious youth have been well documented in the extant literature [16, 17). These social skill deficits among socially anxious teens might prompt negative evaluation from others, which, in turn, might serve to reinforce behavioral avoidance (e.g., evasion of gaze) and negative beliefs, thereby maintaining social anxiety. Social anxiety has also been characterized by deficits in nonverbal communication and social perception [2]. Diminished ability to effectively communicate in social contexts may contribute to social failure, and heightened rejection fears and social anxiety. Such anxiety could, in turn, exacerbate difficulties with social communication via perceptual and attentional biases (e.g., misperceiving benign social cues as threatening) as well as via behavioral avoidance of interpersonal encounters, which provide opportunities to acquire new learning or to practice social skills [18]. Thus, it is possible that social anxiety can stem, at least in part, from SC difficulties during adolescence, as youth face increasing social demands and complexities. As such, SC impairment, if associated with avoidance of social cues, may affect both onset and course of SAD.

Aberrant patterns of visual attention have been shown to contribute to pathological responding within anxious samples relative to control samples [19]. For individuals with SAD, selective attention to threat-related information is present and impairing most often in socially evaluative situations [20, 21]. Biased social attention can give rise to hyperarousal, avoidance, and social withdrawal [22, 23]. Threat related biases in social attention could influence the development of anxious phenotypes which are characterized by difficulties in accurately processing of social stimuli [23]. Although socially anxious youth exhibit selective attention to threatening social stimuli, the direction of attention allocation is equivocal across studies, i.e., toward or away from threat [19]. Traditionally, biases in social attention have been measured using the dot probe task which offers a “snapshot” of social attention [24]. However, the dot probe was not designed to examine extended eye gaze patterns towards social stimuli. As such, consideration is needed to examine the visual attention processes exhibited by socially anxious adolescents across stimulus duration.

The present study addresses a limitation of dot probe research by exploring prolonged social gaze throughout the stimulus duration. Extant research has shown that visual attention toward both angry and happy faces is associated with heightened social anxiety in both pediatric and adult samples [26, 27]. Waters and colleagues [27] also offer insight into how sample characteristics (e.g., anxiety severity, SC impairment) could influence findings. Specifically, Waters and colleagues [27] demonstrated that biased social attention changed as a function of anxiety severity. Understanding if, and how, deficient social communication influences attention to social stimuli (measured via eye gaze) could inform mechanistic treatments for socially anxious youth.

Given the presence of marked impairments in SC skills among youth with SAD [10, 28], this study focused on how SC impairments might predict gaze patterns among socially anxious teens, controlling for the effect of social anxiety severity [27]. Given the hypothesized interrelationships among social anxiety, gaze, and SC difficulties, we were interested in the degree to which SC impairment influences visual social attending above and beyond influence of social anxiety symptoms. Prior research has shown a relationship between gaze and social anxiety symptoms [19] and, separately, a relationship between gaze and SC impairments among other clinical populations [29]. Understanding the effects of SC impairment uniquely among socially anxious teens could contribute to both treatment advances within this socially anxious sample (e.g., treating SC impairment more directly) as well as promote advancement on the progression of SAD-namely that SC impairment could exacerbate socio-cognitive avoidance which then perpetuates and worsens the social anxiety symptoms. Evidence of a relationship between gaze to emotional stimuli and SC impairment would supplement our understanding of attentional bias, which has been largely based on the dot probe paradigm and has not considered the role of SC impairment specifically. Findings have the potential to indicate that social difficulties play a unique role in the maintenance of social anxiety.

Our aims, therefore, were twofold: 1) examine the role of SC impairments within a clinically confirmed socially anxious sample, and 2) explore how social anxiety severity and SC impairment in SAD might influence social gaze. We expected that social anxiety severity would be associated with longer gaze duration, especially for potentially threatening social stimuli, i.e., angry faces [20, 23, 25]. Given that SAD, SC impairment, and visual attention are hypothesized as quite inter-related, this might suggest that SC impairments would also result in longer gaze duration to angry faces. Although we conceptualize SAD, SC impairment, and gaze aversion as inter-related, we also were interested in separating the unique variance explained by each of these variables. Given the notion that SC difficulties underlie the atypical social attending seen in youth with SAD [2], these findings might suggest that perceptual biases are modifiable and serve as viable targets for intervention among socially anxious teenagers. As such, we controlled for social anxiety severity to determine if the observed relationship between SCI and gaze was unique to SCI or, more broadly, a function of anxiety severity which has been found to influence findings in past studies within anxious youth [27].

Method

Procedure

Data were drawn from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a computerized attention training protocol to reduce social anxiety in youth with SAD (masked for review). Participants were recruited through community advertisements, university-affiliated clinics, and referrals from mental health professionals as well as pediatricians and school health services. The study was approved by the human subjects review board; parents provided informed written consent and all adolescents provided informed assent. Here, results focused on the gaze patterns during the administration of the eye-tracking paradigm utilizing the NIMH Child Emotional Faces Picture Set (NIMH-ChEFS; [30]; discussed in further detail below).

Participants

Data from all participants with sufficient pre-treatment eye tracking data from the larger RCT of 58 youth were used (n = 41). The adolescents were between the ages of 12 and 16 years. Parents and adolescents completed a clinical intake which consisted of a semi-structured diagnostic interview (Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV-Child and Parent Versions (ADIS-IV-C/P; [31]) to confirm SAD diagnosis. All participating teens were free from a co-occurring diagnosis of intellectual disability, as confirmed by the two-subtest version of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-II (WASI-II; [32]) as well as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), based on the Social Respnsiveness Scale-Second Edition (SRS-2) [33], a parent-report screening measure. Comorbid anxiety disorders were common within the sample: 61 % of the sample met criteria for generalized anxiety disorder and 34.2% met criteria for a co-occurring specific phobia. Other non-anxiety diagnoses were present but in limited numbers (< 10%). SAD was the reason for referral in all instances. Demographic data are included in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample Descriptive Data.

| Demographic | n = 41 |

|---|---|

| Females (n, %) | 28 (68.3%) |

| Race (n, %) | |

| White | 32 (78) |

| Black | 1 (2.4) |

| Latino | 2 (4.9 |

| Asian | 3 (7.3) |

| Other | 3 (7.3) |

| Age (M, SD) | 14.54 (1.19) |

| IQ (M, SD) | 107.70 (14.72) |

| BFNE-Straightforward Total Score (M, SD) | 28.36 (9.05) |

| SCI (M, SD) | 62.90 (10.80) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder Diagnosis | 25 (60.98) |

| Specific Phobia Diagnosis | 14 (34.15) |

Note. BFNE = Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation-Scale; SCI = SRS-2 Social Communication Index T-score

Measures

Social Responsiveness Scale-Second Edition (SRS-2; [33])

The SRS-2 is a 65-item questionnaire designed to screen for possible ASD. The SRS-2 can also be used to assess SC impariments (outside of ASD) in youth and has been used with anxious samples [10]. Higher scores are indicative of greater social impairment. Parent reports were used to assess the severity of the adolescents' social difficulties. The SRS Social Communication Index (SCI) is a composite of four of the SRS-2 subscales: social awareness, social communication, social information processing, and social motivation (e.g., child would rather be alone that with others; difficulty making friends). Although the SC subscale of the SRS has been used to index change in social disability with treatment (e.g., [34, 35]), little research is available on the use of the SCI composite. The SRS-2 has good convergent validity with the Social Communication Questionnaire [36] which has been used with non-ASD, clinically anxious samples [10] and several studies have found that SRS scores are elevated among youth with mood and anxiety disorders due to SC deficits, e.g., [14, 37]. Overall, these studies suggest that the SRS-2 SCI captures SC impairment, even outside of ASD. Alpha was .88 in the currrent sample.

Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Questionnaire (BFNE; [38])

The BFNE is an abbreviated index of the full version of the FNE [39]. The BFNE consists of 12 items which assesss an indivudal's apprehension or fear of being evaluated negatively by others. FNE is associated with a perceived evaluative threat [39] and considered to be the cognitive determinant in the development and maintenance of SAD [40]. The current DSM-5 [1], relative to previous versions of the DSM, is characterized by a heightened focus on FNE [41]. As such, the BFNE was used as a dimensional index of social anxiety severity. Carleton and colleagues [42] found that the eight straightforward worded items (i.e., excluding the four reverse-scored items) results in the best diagnostic sensitivity and reliability. Thus, the eight straightforward worded items were summed for the total BFNE score in the present study (current sample alpha = .95).

Apparatus and Stimuli

A Tobii T60 XL eye tracker was used to track the adolescents' eye-gaze. Participants were seated about 70 cm from an 18” monitor. All participants were calibrated to the task, which involved tracking a moving red circle located at five predefined locations across the screen (i.e., the four corners and the center of the screen). The tracker's calibration system was set to 0.5 degrees of accuracy with less than 0.3 degrees of visual drift. Following calibration, participants were instructed to look at the facial stimuli in any way they chose to do so (i.e., “Please look at the following faces however you want”). The eye-tracking task lasted about 2.5 minutes following the calibration procedure. Facial stimuli were color photographs from the NIMH-ChEFS [30] with adjustments made by our research team (i.e., standardized luminance, size, and smoothness, removal of non-facial features; masked for review). Although SAD typically first emerges during adolescence, most eye-tracking research to date has focused on adult samples, using stimuli developed for adults. In light of past research which suggests the presence of discrepancies in reaction time responses to adult versus child faces [43] as well as the increased likelihood for adolescents to be evaluated or judged by same age peers [44], the current study examined attention allocation among youth with SAD by using stimuli of adolescent faces. Stimuli consisted of 16 faces displaying anger and 16 faces displaying happiness. All pictures were matched with a neutral expression portrayed by the same actor. The Posner-type eye-tracking paradigm is similar to what has been used in previous research, e.g., [45], which suggests that attention biases are more likely to occur when more than one stimulus is competing for attention [46]. A centered X (1 inch long by 1 inch wide) was presented for 1 second, immediately followed by a face-pair. The face-pair was shown for 3 seconds, during which eye-tracking was measured. After the face-pair, a gray screen was presented for half a second as an inter-trial stimulus. Each stimulus was presented the same number of times to allow for stimulus comparisons.

Data Analyses

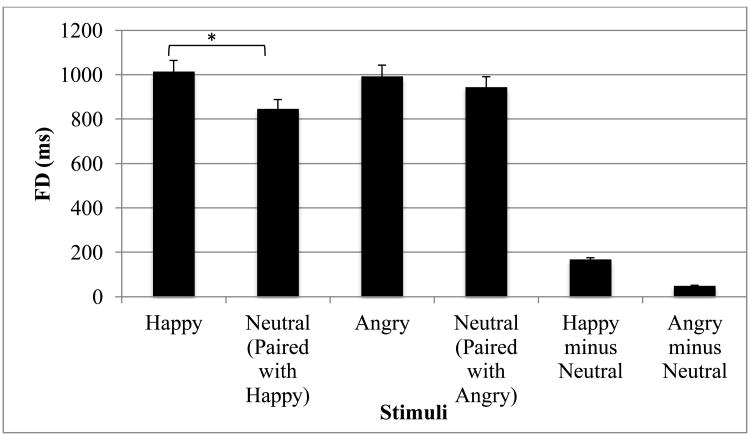

The primary gaze variable of interest was fixation duration (FD), defined as the total length of time (in ms) that a participant fixated on the stimulus. Consistent with extant research, we focused primarily on gaze duration to the whole face, e.g., [45]. The face region was defined from the stimulus' hairline to their chin for each of the presented faces. A fixation was defined as continuous gaze for at least 100 ms. Total FD is regularly used as a measure of preference for looking at one stimulus over another, e.g., [47]. The FD was defined as a continuous gaze metric from avoidance of emotional faces (i.e., gaze preference for neutral information) to vigilance, i.e., gaze preference for emotional faces; see [48]. Dwell time contrast scores were calculated as FD emotional stimulus minus FD paired neutral stimuli (see Figure 1). As such, the primary gaze metric was calculated such that larger scores indicated greater vigilance toward emotional faces and smaller (negative) scores indicated avoidance of emotional faces. In the current analyses, we used a paired sample t-tests to determine whether differences in FD existed between emotional faces versus their respective neutral paired faces. In addition, a series of hierarchical multiple regressions were used to determine if the relationship between SCI and fixation duration to affective face pairs existed independently of social anxiety severity. The power analysis was conducted based on the proposed multivariate regression. With power set at .80 and alpha of .05, a sample size of n=36 would be needed to detect a moderately large effect (Cohens f2=.30).

Figure 1. Fixation duration to stimuli.

Note. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Results

Descriptive statistics were computed to characterize the sample (see Table 1). Skewness and kurtosis for all variables were within acceptable ranges. Basic descriptive statistics (Tables 1 and 2) and regression coefficients (Tables 3 and 4) are presented. Neither participant sex or age were significantly associated with our variables of interest (SRS-2 SCI T-score, BFNE; Table 2). Further, there was no significant correlation between the BFNE and the SCI T-score, which suggests that our independent variables were independent of one another. The correlation coefficient between the SRS-2 SCI T-score and FD to happy-neutral faces was statistically significant (see Table 2).

Table 2. Bivariate Correlations among Study Variables.

| 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | SCI | .04 | .06 | -.01 | .36* | -.01 |

| 2. | BFNE | -- | .06 | -.16 | .16 | .11 |

| 3. | Child Sex | -- | .13 | .11 | -.10 | |

| 4. | Child Age | -- | .12 | .18 | ||

| 5. | FD Happy-Neutral Pairs | -- | -.02 | |||

| 6. | FD Angry-Neutral Pairs | -- |

Note.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

BFNE = Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation-Scale; SCI = SRS-2 Social Communication Index T-score

Table 3. Hierarchical Regression Model for Full Sample: Predictors of Gaze Duration to Happy-Neutral Face Pairs.

| Predictors | B | SE | F | t | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Δ R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .935 | .025 | -.002 | ||||

| BFNE-Straightforward Total | .157 | 5.123 | .967 | ||||

| Step 2 | 4.536* | .201 | .157 | .177 | |||

| BFNE-Straightforward Total | .141 | 4.704 | .943 | ||||

| SRS Social Communication Index | .421** | 3.882 | 2.821 |

Note.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Table 4. Hierarchical Regression Models for Full Sample: Predictors of Gaze Duration to Angry-Neutral Face Pairs.

| Predictors | B | SE | F | t | R2 | Adjusted R2 | Δ R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | .411 | .011 | -.016 | ||||

| BFNE-Straightforward Total | .105 | 6.306 | .641 | ||||

| Step 2 | .200 | .011 | -.044 | .000 | |||

| BFNE-Straightforward Total | .105 | 6.398 | .632 | ||||

| SRS Social Communication Index | .000 | 5.281 | .002 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001

Examining FD to the face region of happy stimuli compared to its paired neutral stimuli, participants were found to spend more time fixating to the facial region of the happy face (M=1014.13 ms, SD=327.65) than to the neutral face (M=846.39 ms, SD=255.56); t(40)= 3.57, p < .001, Cohen's d=.558; Figure 1. When examining FD to the face region of angry stimuli compared to its paired neutral stimuli participants spent no more time fixating to the face region of the angry face (M=993.75, SD=255.56) compared to the neutral stimuli (M=944.20, SD=252.50); t(40)= .93 p = .358, Cohen's d=.145; Figure 1.

Separate regression analyses for happy-neutral pairs and angry-neutral pairs were examined. In the first step of the hierarchical multiple regression for the happy-neutral pairs, significant main effects did not emerge for the BFNE. However, significant main effects did emerge for the SCI T-score such that SC deficits were positively associated with dwell time contrast scores toward happy faces, independent of BFNE (Table 3). Dwell time contrast scores (happy FD minus neutral when paired with happy FD) were positive, reflecting more gaze toward happy faces relative to the neutral face with which it was paired. These variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in fixation duration to happy faces [adjusted R2 =.201, F(2, 38) = 4.536, p = .018]. SC impairment contributed an additional 17.7% variance in fixation duration to happy faces (Cohens f2=.252).

In the first step of the hierarchical multiple regression for the angry-neutral pairs, significant main effects did not emerge for the BFNE or the SCI T-score (Table 4). Dwell time contrast scores (angry FD-neutral paired with angry FD) were positive, reflecting more gaze toward angry faces relative to the neutral face; however this difference was not related to any of the proposed predictors of variance in gaze.

Discussion

The current study provides an examination of how SC impairment in a sample of adolescents with SAD affects gaze patterns to social stimuli. Among youth with SAD, SC impairment predicted unique variance in terms of greater fixation duration to happy faces. In contrast, no significant relationship was observed between fixation duration to angry or neutral faces and SC impairment. Further, we did not find evidence of significant contributions of social anxiety severity on gaze duration to happy-neutral face pairs or angry-neutral face pairs. Past research by Shechner and colleagues [23] suggests that SAD youth demonstrated sustained selective attention directed to angry faces. However, in our sample, socially anxious youth demonstrated a statistically significant dwell time contrast score towards happy faces, not angry or neutral faces. The association between social anxiety severity and FD to happy faces was not statistically significant which was surprising given the hypothesized inter-relationships among social anxiety, SC deficits, and gaze patterns. As such, the observed relationship between SC difficulties and gaze was unique to SC impairments rather than a function of anxiety severity which has found to influence findings in past studies within anxious youth [27]. Despite the hypothesized inter-relationships among social anxiety, gaze, and SC difficulties, our findings suggest that there was not a relationship between social anxiety symptoms, as measured by the BFNE, and visual social attending. Our results suggest that understanding how SC impairment uniquely effects social attention among socially anxious teens could contribute to treatment refinement (e.g., treating SC impairment more directly to target social avoidance). Perhaps consideration of underlying social processes that are not a direct link to SAD severity, (e.g., SC impairment), might explain the variability seen in eye gaze research in SAD, as we next suggest.

It is possible that happy faces might serve as a safety signal or protective factor from peer rejection for youth with SAD, thus resulting in longer fixation durations. Although speculative, happy faces might reinforce visual attention. In other words, their signaling of positive social regard might be more meaningful to socially anxious youth who are more socially impaired, who then attend more to these signals. Given the presence of these heightened SC difficulties and difficulties in peer relationships, youth with SAD might look longer towards happy faces instead of neutral or ambiguous faces in order to receive positive social feedback from peers. Further, parent-reported deficits in SC among youth with SAD are linked to a perceptual bias towards happy faces. Given the potential for atypical social attending among teenagers with SAD, we anticipate that these findings can provide guidance to intervention research, for example in refining behavioral treatments for SAD related to conducting effective exposures (e.g., understanding if an individual avoids or attends to certain emotional stimuli). As such, further examination in terms of how our results might transfer to treatments for SAD is warranted.

It is also important to consider how methodological factors, such as stimuli choice, might have impacted the present findings. It has been found that youth are slower to respond to adult faces, compared to child faces [49, 50], possibly due to the fact that youth are more likely to be socially evaluated by their peers than adults [44]. Accordingly, the use of teen faces as stimuli, such as in this study, may be an important consideration in future research [e.g., 23]. Lastly, analyses involved multiple informants (child, parent), which in turn reduces informant bias within our findings.

The primary limitation of this study was its small sample size, which limited our ability both detect small effect sizes [51] and to explore potentially clinically meaningful differences among different subgroups based on comorbidity. Biased attention has been reported for individuals with other internalizing disorders (outside of SAD), and therefore, the co-morbid psychiatric disorders in our sample (i.e., other anxiety disorders) may have influenced the findings in this study. It is just as likely however that the co-morbid diagnoses have reduced the effects found. While majority of our sample had at least one comorbid diagnosis, the primary presenting concern was social anxiety, therefore, allowing us to generalize our results to those individuals with a primary diagnosis of SAD. Additionally, our sample was predominantly Caucasian, which limits the ability to generalize the results to diverse races and ethnicities. Nevertheless, this is a preliminary study with a well-characterized clinical sample. Additionally, the present study only included happy, neutral, and angry faces. Future research should explore the relationship between SC impairments and gaze duration to other emotions (e.g., fear, disgust). Future research should also consider how fear of positive evaluation (FPE) might influence visual attention among socially anxious adolescents. FPE consists of irrational and persistent fears of receiving social feedback which might threaten an individual's ability to maintain a low profile [52], which might influence gaze patterns to happy faces among youth with SAD. However, given that FNE and FPE are strongly, positively associated [52], it is unlikely that differences between FNE and FPE in relation to gaze duration to happy faces would be observed. As such, future research is warranted. Despite the limitations, these findings underscore the importance of considering SC impairments which might influence social attention, particularly to happy faces, among teenagers with SAD.

The majority of extant research points to differences in visual attention to threat related stimuli among socially anxious youth. However, our results do not provide evidence for an association between SC impairment and attending to threat cues; in contrast, we found that SC impairment contributes to increased gaze toward nonthreatening stimuli. This finding warrants further examination and replication. As highlighted by Wieser and colleagues [53], individuals with high social anxiety severity may show a preference for happy faces. Our results, however, were unrelated to social anxiety severity and support the role of SC impairment in predicting social gaze towards happy faces. Therefore, it seems equally important to evaluate how socially anxious youth view happy stimuli, especially while considering variability in regards to SC impairment. Given the role of SC impairment on social gaze, our findings offer further support for the clinical import of social skills interventions as a particularly helpful intervention for youth with heightened SC difficulties in order to prevent the further development of heightened, or perhaps the development of clinical, SAD [12, 54].

Summary

Results from the present study suggested that within a sample of socially anxious teenagers, SC impairment predicted greater fixation duration toward happy faces, controlling for social anxiety severity. In addition, no significant relationship was observed between SC impairment and fixation duration to angry or neutral faces. For socially anxious adolescents, heightened SC difficulties might give rise to longer fixation duration toward happy faces instead of evaluative or ambiguous faces. One potential explanation is that socially anxious youth with social impairment seek out positive valence social cues as a means to receive positive social feedback. These results underscore the importance of evaluating underlying social processes which are not directly linked to SAD severity, (e.g., SC impairment), in order to explain patterns of social attention and avoidance among socially anxious youth.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health, Grant R34 [PI: Ollendick].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards: Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent: All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board for human subject research. All participants provided informed consent.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th. American Psychiatric Publication; New York: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rapee RM, Spence SH. The etiology of social phobia: empirical evidence and an initial model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2004;24:737–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borowski SK, Zeman J, Braunstein K. Social anxiety and socioemotional functioning during early adolescence: the mediating role of best friend emotion socialization. J Early Adolesc. 2016 Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weems CF, Costa NM. Developmental differences in the expression of childhood anxiety symptoms and fears. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005;44:656–663. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000162583.25829.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartwright-Hatton S, Tschernitz N, Gomersall H. Social anxiety in children: social skills deficit, or cognitive distortion? Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muris P, Merckelbach H, Damsma E. Threat perception bias in nonreferred, socially anxious children. J Clin Child Psychol. 2000;29:348–359. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horley K, Williams LM, Gonsalvez C, Gordon E. Face to face: visual scanpath evidence for abnormal processing of facial expressions in social phobia. Psychiatry Res. 2004;127:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moukheiber A, Rautureau G, Perez-Diaz F, Soussignan R, Dubal S, Jouvent R, Pelissolo A. Gaze avoidance in social phobia: objective measure and correlates. Behav Res Ther. 2010;48:147–151. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haller SP, Kadosh KC, Lau JY. A developmental angle to understanding the mechanisms of biased cognitions in social anxiety. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:846. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halls G, Cooper PJ, Creswell C. Social communication deficits: specific associations with social anxiety disorder. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieckowski AT, White SW. Application of technology to social communication impairment in childhood and adolescence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;74:98–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickard H, Rijsdijk F, Happé F, Mandy W. Are social and communication difficulties a risk factor for the development of social anxiety? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Steensel FJ, Bögels SM, Wood JJ. Autism spectrum traits in children with anxiety disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:361–370. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1575-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Towbin KE, Pradella A, Gorrindo T, Pine DS, Leibenluft E. Autism spectrum traits in children with mood and anxiety disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:452–464. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corbett BA, Key AP, Qualls L, Fecteau S, Newsom C, Coke C, Yoder P. Improvement in social competence using a randomized trial of a theatre intervention for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46:658–672. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2600-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beidel DC, Turner SM, Morris TL. Psychopathology of childhood social phobia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:643–650. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spence SH, Donovan C, Brechman-Toussaint M. Social skills, social outcomes, and cognitive features of childhood social phobia. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108:211–221. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White SW, Schry AR, Kreiser NL. Social worries and difficulties: Autism and/or social anxiety disorder? Springer; New York, NY: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shechner T, Britton JC, Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, Ernst M, Fox NA, et al. Attention biases, anxiety, and development: toward or away from threats or rewards? Depress Anxiety. 2012;29:282–294. doi: 10.1002/da.20914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong T, Olatunji BO. Eye tracking of attention in the affective disorders: a meta-analytic review and synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32:704–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spector IP, Pecknold JC, Libman E. Selective attentional bias related to the noticeability aspect of anxiety symptoms in generalized social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2003;17:517–531. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emot. 2010;10:349–357. doi: 10.1037/a0018486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shechner T, Jarcho JM, Britton JC, Leibenluft E, Pine DS, Nelson EE. Attention bias of anxious youth during extended exposure of emotional face pairs: an eye-tracking study. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:14–21. doi: 10.1002/da.21986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley BP, Mogg K, Millar NH. Covert and overt orienting of attention to emotional faces in anxiety. Cogn Emot. 2000;14:789–808. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schofield CA, Inhoff AW, Coles ME. Time-course of attention biases in social phobia. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley BP, Mogg K, White J, Groom C, De Bono J. Attentional bias for emotional faces in generalized anxiety disorder. Br J Clin Psychol. 1999;38:267–278. doi: 10.1348/014466599162845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waters AM, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in children with generalized anxiety disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:435–442. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181642992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyson KE, Cruess DG. Differentiating high-functioning autism and social phobia. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1477–1490. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White SW, Maddox BB, Panneton RK. Fear of negative evaluation influences eye gaze in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:3446–3457. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egger HL, Pine DS, Nelson E, Leibenluft E, Ernst M, Towbin KE, Angold A. The NIMH Child Emotional Faces Picture Set (NIMH-ChEFS): a new set of children's facial emotion stimuli. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2011;20:145–156. doi: 10.1002/mpr.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman WK, Albano AM. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM IV (Child and Parent Versions) Psychological Corporation 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wechsler D. WASI-II: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence-Second Edition. Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Constantino JN, Gruber CP. Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2) Western Psychological Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laugeson EA, Gantman A, Kapp SK, Orenski K, Ellingsen R. A randomized controlled trial to improve social skills in young adults with autism spectrum disorder: the UCLA PEERS® Program. J Autism Dev Disord. 2015;45:3978–3989. doi: 10.1007/s10803-015-2504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White SW, Schry AR, Miyazaki Y, Ollendick TH, Scahill L. Effects of verbal ability and severity of autism on anxiety in adolescents with ASD: one-year follow-up after cognitive behavioral therapy. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44:839–845. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.893515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutter M, Bailey A, Lord C. SCQ The Social Communication Questionnaire. Western Psychological Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Settipani CA, Puleo CM, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Characteristics and anxiety symptom presentation associated with autism spectrum traits in youth with anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leary MR. A brief version of the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1983;9:371–375. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1969;33:448–457. doi: 10.1037/h0027806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heimberg RG, Hofmann SG, Liebowitz MR, Schneier FR, Smits JAJ, Stein MB, et al. Craske MG. Social anxiety disorder in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:472–479. doi: 10.1002/da.22231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carleton RN, Collimore KC, McCabe RE, Antony MM. Addressing revisions to the Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation scale: measuring fear of negative evaluation across anxiety and mood disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:822–828. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mogg K, Bradley BP, De Bono J, Painter M. Time course of attentional bias for threat information in non-clinical anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ollendick TH, Benoit K, Grills-Taquechel AE. Social anxiety in children and adolescents. John Wiley & Sons, LTD; New York, NY: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garner M, Mogg K, Bradley BP. Orienting and maintenance of gaze to facial expressions in social anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:760–770. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.In-Albon T, Kossowsky J, Schneider S. Vigilance and avoidance of threat in the eye movements of children with separation anxiety disorder. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38:225–235. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9359-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Klin A, Jones W, Schultz R, Volkmar F, Cohen D. Visual fixation patterns during viewing of naturalistic social situations as predictors of social competence in individuals with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:809–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.9.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Price RB, Rosen D, Siegle GJ, Ladouceur CD, Tang K, Allen KB, et al. From anxious youth to depressed adolescents: prospective prediction of 2-year depression symptoms via attentional bias measures. J Abnorm Psychol. 2016;125:267–278. doi: 10.1037/abn0000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benoit KE, McNally RJ, Rapee RM, Gamble AL, Wiseman AL. Processing of emotional faces in children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. Behav Change. 2007;24:183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gamble AL, Rapee RM. The time-course of attentional bias in anxious children and adolescents. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:841–847. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weeks JW, Heimberg RG, Rodebaugh TL. The Fear of Positive Evaluation Scale: assessing a proposed cognitive component of social anxiety. J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wieser MJ, Pauli P, Weyers P, Alpers GW, Mühlberger A. Fear of negative evaluation and the hypervigilance-avoidance hypothesis: an eye-tracking study. J Neural Transm. 2009;116:717–723. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.White SW, Ollendick T, Albano AM, Oswald D, Johnson C, Southam-Gerow MA, et al. Randomized controlled trial: multimodal anxiety and social skill intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:382–394. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1577-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]