Abstract

Introduction

Lifestyle factors may influence brain health in midlife. Functional magnetic resonance imaging is a widely used tool to investigate early changes in brain health, including neurodegeneration. In this systematic review, we evaluate the relationship between lifestyle factors and neurodegeneration in midlife, as expressed using functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO combining subject headings and free text terms adapted for each database. Articles were screened, and their quality was assessed independently by two reviewers before final inclusion in the review.

Results

We screened 4116 studies and included 29 in the review. Seven lifestyle factors, such as alcohol, cognitive training, excessive internet use, fasting, physical training, smoking, and substance misuse, were identified in this review.

Discussion

Cognitive and physical trainings appear to be associated with a neuroprotective effect, whereas alcohol misuse, smoking, and substance misuse appear to be associated with neurodegeneration. Further research is required into the effects of excessive internet use and fasting.

Keywords: Neurodegeneration, Neuroprotection, Magnetic resonance imaging, Life Style, Middle aged

Highlights

-

•

Seven lifestyle factors related to brain health in midlife were identified.

-

•

Cognitive training and physical training likely have a neuroprotective effect.

-

•

Alcohol, smoking, and substance misuse probably have a neurodegenerative effect.

-

•

There is limited evidence on the effect of excessive internet use on brain health.

-

•

There is limited evidence on the effect of fasting on brain health.

1. Background

There is increasing recognition that neurodegenerative diseases, which manifest clinically as dementia in later life, have their origins in midlife, or even earlier [1]. Recent research on cognitive, neuroimaging, and biological markers suggest that changes in several parameters may well precede overt clinical symptoms by not just many years, but decades [2]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) offers considerable promise as a marker for neurodegenerative disease. It could also be of value in monitoring disease progression and response to interventions [3] such as lifestyle modification. In midlife, lifestyle modification could potentially alter neurodegenerative disease progression and thereby reduce an individual's risk of dementia in later life [4]. If this were the case, it is critical to identify which potentially modifiable lifestyle factors are associated with neurodegeneration in midlife. Therefore, in the absence of any previous systematic reviews, we evaluate the relationship between lifestyle factors and neurodegeneration in midlife as expressed on fMRI in the published literature.

2. Methods

2.1. Identification of studies

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO were searched via the OVID platform on 5th December 2016. MEDLINE was searched from 1946 to November 2016, EMBASE from 1980 to November 2016, PsycINFO from 1806 to November 2016. There were no limits on language or publication dates. A specific search was constructed for each database using subject headings and free text terms, and these can be found in the Supplementary Material. The search terms covered the areas of neuroimaging, lifestyle, and regional changes in cerebral metabolism or blood flow, blood volume, or oxygenation.

The systematic review aimed to include all published studies that assessed the relationship between lifestyle factors and neurodegeneration, neuroprotection, or both as expressed on fMRI in midlife. A study was defined as having assessed individuals in midlife if it included individuals aged 40–59 years or if two standard deviations around the mean fell within the 40–59 years age range. Neurodegeneration was defined as any pathological condition primarily affecting neurons [5]. Neuroprotection was considered to be an effect that may result in salvage, recovery, or regeneration of the nervous system, its cells, structure, and function [6]. The exposure in the review was lifestyle factors, as defined by the World Health Organization: “Lifestyle is a way of living based on identifiable patterns of behavior, which are determined by the interplay between an individual's personal characteristics, social interactions, and socioeconomic and environmental living conditions” [7]. The outcome in the systematic review was the numerical outcome measures derived from the fMRI scan. fMRI is a brain imaging technique to capture regional changes in cerebral metabolism or in blood flow, volume, or oxygenation in response to task activation or during rest [8]. The systematic review aimed to include studies using both resting-state and task-based fMRI experimental protocols and studies assessing the general population and those conducted in a general medical setting. There were no limits by language or publication date.

2.2. Eligibility

The inclusion/exclusion criteria for the systematic were as follows:

- Inclusion criteria

-

i.Original human research study.

-

ii.Population includes a lifestyle factor in midlife.

-

iii.Study includes an fMRI outcome in midlife.

-

i.

- Exclusion criteria

-

i.Not an original human research study.

-

ii.Study population has a diagnosis of dementia either in general or based on specific subtypes classified using standard diagnostic criteria, for example, the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association [9].

-

iii.Study population does not include a lifestyle factor in midlife.

-

iv.Study population does not include individuals in midlife.

-

v.The aim of the study is not to look at the effect of a lifestyle factor on fMRI outcome.

-

vi.fMRI outcome is not a proxy for neurodegeneration or neuroprotection.

-

i.

2.3. Study selection and data collection

The titles and abstracts of all articles identified by the search were screened independently by two reviewers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria with any disagreements in the final lists of included studies resolved by discussion. Potentially relevant articles were then retrieved and examined against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Differences between reviewers' selections were again resolved by discussion. Data were extracted from included articles by one reviewer on the number of study participants, mean age, standard deviation and age range of participants, study methodology and design, and the key findings from the study related to this systematic review.

2.4. Quality of evidence

The quality of studies was assessed using a modified version of the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool [10] tailored to the literature being assessed in this review. This tool has been judged suitable for use in a systematic review [11] and forms a global quality rating for a paper based on six assessment criteria: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection method, and withdrawals and dropouts.

2.5. Protocol and registration

The systematic review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, registration number CRD42016045237 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/).

3. Results

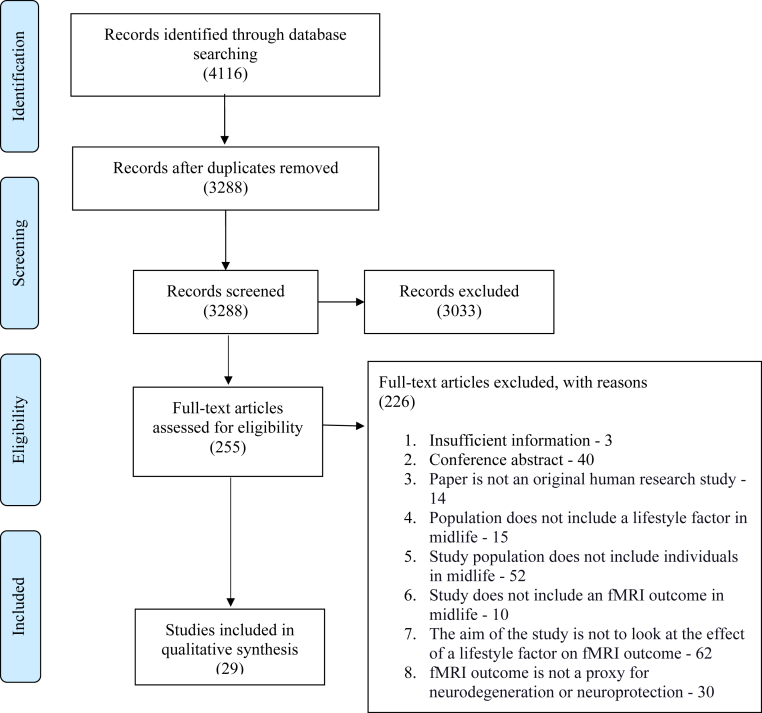

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram (Fig. 1) for the screening and selection of studies shows that 4116 records were identified through database searches. Following de-duplication and title and abstract screening, 255 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility. After excluding 226 articles for the reasons outlined in Fig. 1, a total of 29 articles were included in the systematic review. Table 1 gives a summary overview of the 29 articles included in the systematic review, arranged by lifestyle factors. Table 2 then summarizes the key findings from the 29 individual articles.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram showing the selection of studies from search to inclusion.

Table 1.

Summary of evidence for each lifestyle factor identified in the systematic review

| Lifestyle factor | Number of studies | Quality assessment rating of studies | Overall effect—neurodegenerative or neuroprotective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical training | 7 | Moderate: 2 studies Strong: 5 studies |

Neuroprotective |

| Cognitive training | 3 | Strong: 3 studies | Neuroprotective |

| Fasting | 1 | Weak: 1 study | Neuroprotective |

| Substance misuse | 12 | Weak: 4 studies Moderate: 4 studies Strong: 4 studies |

Neurodegenerative |

| Alcohol | 6 | Weak: 3 studies Moderate: 3 studies |

Neurodegenerative |

| Smoking | 3 | Weak: 1 study Moderate: 1 study Strong: 1 study |

Neurodegenerative |

| Excessive internet use | 1 | Moderate: 1 study | Neurodegenerative |

Table 2.

Individual studies reporting on the relationship between lifestyle factors and neurodegeneration in midlife as expressed on fMRI

| Study | Lifestyle factor | N | Mean age (SD)/Range | Methodology/design | Findings | Quality assessment rating | Neurodegenerative or neuroprotective effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bednarski et al. [12] | Substance misuse | 50 (cocaine dependence 23/healthy controls 27). | Cocaine dependence: 36.2 (6.3)/NA. Healthy controls: 34.9 (6.5)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: one sample and two-sample t-tests. |

Cocaine dependence is associated with dysfunction of the default mode network. | Moderate | Neurodegenerative |

| Belaich et al. [13] | Fasting | 6 males. | 41 (NA)/34 – 48. | Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: ANOVA test. |

There is a significant difference between maximal BOLD-fMRI signal before and during fasting. | Weak | Neuroprotective |

| Castelluccio et al. [14] | Substance misuse | 94 (cocaine users 30/former users 29/healthy controls 35). | Cocaine users: 37.6 (7.3)/21–45. Former users: 40.3 (6.4)/22–50. Healthy controls: 35.8 (10)/21–58. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: regression analysis. |

The cocaine user groups exhibited significantly increased BOLD activity relative to healthy controls in several a priori regions of interest. | Weak | Neurodegenerative |

| Chapman et al. [15] | Physical training | 37 (physical training 18/control 19). | 64 (3.9)/57–75. | Study type: controlled clinical trial. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: general statistical linear model. |

There is higher resting CBF in the anterior cingulate region in the physical training group compared to the control group. | Strong | Neuroprotective |

| Chapman et al. [16] | Cognitive training | 37 (cognitive training 18/control 19). | 62.9 (3.6)/56–71. | Study type: controlled clinical trial. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: general statistical linear model. |

There was increased global and regional CBF particularly in the default mode network and the central executive network in the cognitive training group. | Strong | Neuroprotective |

| Chapman et al. [17] | Physical or cognitive training | 36 (physical training 18/cognitive training 18). | Physical training: 64 (4.3)/56–75. Cognitive training: 61.8 (3.3)/56–75. |

Study type: randomized control trial. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: general statistical linear model. |

There were multiple distinct changes on fMRI that suggest that aerobic exercise and cognitive reasoning training contribute differentially to brain health. | Strong | Neuroprotective |

| Durazzo et al. [18] | Smoking | 61 (smokers 34/nonsmokers 27). | Smokers: 47.3 (10.5)/NA. Nonsmokers: 47.3 (11.9)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: multivariate analysis of covariance. |

Smokers showed significantly lower perfusion than nonsmokers in multiple brain regions including regions implicated in early Alzheimer's disease (cingulate, right isthmus of the cingulate, right supramarginal gyrus, and bilateral inferior parietal lobule). | Weak | Neurodegenerative |

| Gazdzinski et al. [19] | Alcohol and smoking | 48 (nonsmoking light drinkers 19/nonsmoking alcoholics 10/smoking alcoholics 19). | Nonsmoking light drinkers: 47 (7.9)/26–66. Nonsmoking alcoholics: 50.9 (10)/26–66. Smoking alcoholics: 48 (9.9)/26–66. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: MANOVA; Wilks' λ. |

Alcoholics, as a group, showed lower frontal gray matter perfusion and lower parietal gray matter perfusion than nonsmoking light drinkers. In smoking alcoholics, a higher number of cigarettes smoked per day was associated with lower perfusion. |

Moderate | Neurodegenerative |

| Hart et al. [20] | Physical training | 52 (ex-NFL players 26/healthy controls 26). | Ex-NFL players: 61.8 (NA)/41–79. Healthy controls: 60.1 (NA)/41–79. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: NA. |

Altered CBF patterns in retired NFL players are concordant with brain regions associated with abnormal findings on neuropsychological testing. | Strong | Neurodegenerative |

| Hermann et al. [21] | Alcohol | 18 (alcohol dependence 9/healthy volunteers 9). | Alcohol dependence: 40.2 (5.6)/NA. Healthy control: 41.8 (13.2)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: general statistical linear model. |

Alcohol-dependent patients showed a significantly lower BOLD signal in an extended bilateral occipital area as compared with healthy controls. | Weak | Neurodegenerative |

| Hotting et al. [22] | Physical and cognitive training | 33 (cycling and spatial 8, cycling and perceptual 8, stretching and spatial 9, stretching and perceptual 8). | Cycling and spatial: 50.25 (4.2)/40–55. Cycling and perceptual: 49 (4.28)/40–55. Stretching and spatial: 50.22 (2.91)/40–55. Stretching and perceptual: 46 (3.89)/40–55. |

Study type: controlled clinical trial. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: one and two-sample t-tests, a flexible factorial model and full factorial model. |

Participants of the spatial training group showed lower activity than participants of the perceptual training group in a network of brain regions associated with spatial learning, including the hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. | Strong | Neuroprotective |

| Hu et al. [23] | Substance misuse | 112 (cocaine users 56/healthy controls 56). | Cocaine users: 39.86 (6.71)/NA. Healthy controls: 38.70 (10.9)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: ANOVA test. |

Compared with healthy controls, the cocaine user group showed differing patterns of rsFC in multiple brain regions. | Moderate | Neurodegenerative |

| Ide et al. [24] | Substance misuse | 163 (cocaine dependent 75/healthy controls 88). | Cocaine dependent: 39.9 (7.6)/NA. Healthy controls: 38.7 (10.9)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: two-sample t-tests and multiple regression. |

Compared with healthy controls, cocaine-dependent individuals showed decreased PSS and PSSI in multiple frontoparietal regions. | Moderate | Neurodegenerative |

| Jiang et al. [25] | Substance misuse | 48 (chronic heroin users 24/normal controls 24). | Chronic heroin users: 35.67 (5.66)/NA. Normal controls: 35.38 (6.02)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: two-sample t-tests and a Pearson correlation analysis. |

Compared with controls, heroin addicts had altered ALFF in multiple brain regions. | Strong | Neurodegenerative |

| Kelly et al. [26] | Substance misuse | 49 (cocaine dependent 25/healthy comparisons 24). | Cocaine-dependent adults: 35.0 (8.8)/NA. Healthy comparisons: 35.1 (7.5)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: NA. |

Reduced prefrontal interhemispheric rsFC in cocaine-dependent participants relative to control subjects and a cocaine dependence-related reduction in interhemispheric RSFC among nodes of the dorsal attention network. | Strong | Neurodegenerative |

| Kim et al. [27] | Excessive internet and alcohol use | 45 (internet gaming disorder 16/alcohol use disorder 14/healthy controls 15). | Internet gaming disorder: 21.63 (5.92)/NA. Alcohol use disorder: 28.64 (5.92)/NA. Healthy controls: 25.40 (5.92)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: two-sample t-tests. |

There were distinctive functional changes in the resting-state of patients with internet gaming disorder, in addition to common ReHo changes in the internet gaming disorder and alcohol use disorder group. | Moderate | Neurodegenerative |

| Lee et al. [28] | Substance misuse | 23 (chronic cocaine abusers 13/healthy controls 10). | Chronic cocaine abusers: 38 (6)/28–45. Healthy controls: 36 (6)/27–44. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: ANOVA, post hoc t-test, Pearson product moment correlations. |

Chronic cocaine abusers showed significantly enhanced positive BOLD response to photic stimulation when compared with control subjects. | Weak | Neurodegenerative |

| Liu et al. [29] | Substance Misuse | 26 (cocaine addict 13/ control subjects 13). | Cocaine-addicted subjects: 46.6 (6.9)/NA. Control subjects: 44.4 (6.0)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, Mann–Whitney U test, linear regression. |

In cocaine-addicted subjects, cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen, a surrogate marker of aggregated neural activity, was significantly lower than that in controls. | Weak | Neurodegeneration |

| MacIntosh et al. [30] | Physical Training | 30 men with coronary artery disease. | 65 (7)/55–80 | Study type: cohort study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: linear regression analysis. |

Perfusion was associated with fitness at baseline and with greater fitness gains with exercise. | Moderate | Neuroprotection |

| May et al. [31] | Substance misuse | 42 (recently abstinent methamphetamine dependent 25/healthy controls 17). | Abstinent methamphetamine-dependent individuals: 38.84 (9.16)/NA. Healthy controls: 38.77 (9.40)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: linear mixed effects analysis. |

Methamphetamine-dependent individuals exhibited lower anterior insula, dorsal striatum, and thalamus activation than healthy controls, across anticipatory and stimulus-related processing. | Weak | Neurodegeneration |

| McFadden et al. [32] | Physical Training | 12 overweight/obese adults. | 38.2 (9.5)/NA. | Study type: cohort study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: t- test. |

A 6-month exercise intervention was associated with a reduction in default mode network activity in the precuneus. | Moderate | Neuroprotection |

| Mitchell et al. [33] | Substance misuse | 32 (cocaine dependence 16/healthy controls 16). | Cocaine dependence: 39 (10.4)/NA. Healthy controls: 40 (7.4)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: two-sample t-tests. |

Cocaine-dependent patients displayed less overall intrinsic connectivity compared with healthy controls. | Strong | Neurodegeneration |

| Mon et al. [34] | Smoking | 69 (nonsmoking light drinker 28, nonsmoking alcoholic 19, smoking alcoholic 22). | Nonsmoking light drinker: 44 (8.2)/28–68. Nonsmoking alcoholic: 52.1 (9.4)/28–68. Smoking alcoholic: 47.8 (9.2)/28–68. |

Study type: Cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: generalized linear model. |

After 5 weeks of abstinence, perfusion of frontal and parietal gray matter in nonsmoking alcoholics was significantly higher than that at baseline. The total number of cigarettes smoked per day was negatively correlated with frontal gray matter perfusion. |

Strong | Neurodegeneration |

| Murray et al. [35] | Substance misuse | 77 (alcohol-dependent 26, polysubstance use 20, light or nondrinkers 31). | Alcohol dependent: 54 (10)/NA. Polysubstance use: 45 (9)/NA. Light or nondrinkers: 47 (11)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: analyses of covariance. |

Regional perfusion was significantly lower in alcoholics compared with light or nondrinkers. Greater smoking severity correlated with lower perfusion in alcohol-dependent individuals. |

Strong | Neurodegeneration |

| Rogers et al. [36] | Alcohol | 20 (alcoholic 10/healthy controls 10). | Alcoholic: 43 (12)/18–70. Control: 40 (13)/18–70. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: two-sample t-test. |

Recently abstinent alcoholic patients showed deficits in functional connectivity and recruitment of additional brain regions for the performance of a simple finger-tapping task. | Weak | Neurodegeneration |

| Sullivan et al. [37] | Alcohol | 24 (alcoholics 12/control subjects 12). | Alcoholics: 45.7 (4.4)/38–54. Control subjects: 46.3 (5.2)/38–54. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: task-based. Statistical method: ANOVA. |

Alcoholics showed selective differences from control subjects in the CBF pattern in the anterior precuneus and CBF level in the insula, a hub of the salience network. | Moderate | Neurodegeneration |

| Wang et al. [38] | Substance misuse | 39 (cocaine addict 20/healthy controls 19). | Cocaine addict: 42.15 (4.3)/NA. Healthy controls: 39.9 (4.5)/NA. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: two-sample t-test and simple regression. |

Compared with controls, cocaine-addicted participants showed hypoperfusion and reduced irregularity of resting-state activity in multiple brain regions. | Moderate | Neurodegeneration |

| Weiland et al. [39] | Alcohol | 470 (problematic alcohol use 383/controls 87). | Problematic alcohol use: 31.1 (9.3)/21–56. Controls: 25.8 (8.3)/21–53.3. |

Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: multivariate analysis of variance. |

Individuals with problematic alcohol use had significantly lower network connectivity strength than controls in the left executive control network, basal ganglia, and primary visual networks. | Weak | Neurodegeneration |

| Xu et al. [40] | Physical training | 59 healthy adults. | 66.68 (9.63)/NA. | Study type: cross-sectional study. fMRI type: resting-state. Statistical method: general linear model. |

Women who engaged in strength training at least once per week exhibited significantly greater cerebrovascular perfusion than women who did not. | Strong | Neuroprotection |

Abbreviations: ALFF, amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation; ANOVA, analysis of the variance; BOLD, blood oxygenation level dependent; CBF, cerebral blood flow; MANOVA, multivariate analyses of variance; NA, not available; PPS, post signal slowing; PSSI, power spectrum scale invariance; ReHo, regional homogeneity; rsFC, resting-state Functional Connectivity; SD, standard deviation; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; NFL, National Football League.

3.1. Alcohol

Of the six studies looking at the effect of alcohol as expressed on fMRI, three used a task-based fMRI protocol, and three studies used a resting-state protocol. Of the resting-state studies, Gazdzinski et al. [19] demonstrated the evidence that concurrent alcohol dependence and chronic cigarette smoking are associated with regional gray matter hypoperfusion. Kim et al. [27] showed increased regional homogeneity (ReHo) in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) executive control, basal ganglia, and primary visual networks. Weiland et al. [39] found significantly lower network connectivity strength than controls in the left executive control, basal ganglia, and primary visual networks. For the task-based studies, Hermann et al. [41] described significantly lower blood-oxygen-level dependent signal in an extended bilateral occipital area as compared with healthy controls during a visual and acoustic simulation task. Rogers et al. [36] described a pattern in recently abstinent alcoholic patients of specific deficits in functional connectivity and recruitment of additional brain regions for the performance of a simple finger-tapping task. Sullivan et al. [37] demonstrated that alcoholics have selective differences from control subjects in the cerebral blood flow (CBF) pattern in the anterior precuneus and CBF level in the insula, a hub of the salience network.

3.2. Cognitive training

Three studies looked at the effect of cognitive training as expressed on fMRI. Chapman et al. [16] examined changes in brain health, pre-, mid-, and post-training in 37 adults who received 12-week strategy-based cognitive training versus a control group. They found increases in global and regional CBF, particularly in the default mode network (DMN) and the central executive network. In addition, they found greater connectivity in these same networks. In a follow-up, randomized control trial comparing the effects of two training protocols, cognitive training and physical training, Chapman et al. [17] describe preliminary evidence that increased cognitive and physical activities improve brain health in distinct ways. Cognitive reasoning training-enhanced frontal networks are shown to be integral to top-down cognitive control and brain resilience. In a controlled clinical trial, Hotting et al. [22] compared effects of cognitive training (spatial vs. perceptual training) and physical training (endurance training vs. nonendurance training) on spatial learning in 33 adults. Spatial learning was assessed with a virtual maze task, and at the same time, neural correlates were measured with fMRI. Only spatial training improved performance in the maze task. This improvement was accompanied by a decrease in frontal and temporal lobe activity.

3.3. Excessive internet use

Kim et al. [27] assessed the resting-state brain of individuals who were diagnosed with internet gaming disorder (IGD), as defined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [42], scored over 70 on Young's Internet Addiction Test [43], and who spent more than 4 hours/day and 30 hours per week using the internet. These individuals were compared with patients with alcohol use disorder and healthy controls. Using ReHo measures, Kim et al. [27] found increased ReHo in the PCC of the IGD and alcohol use disorder groups, and decreased ReHo in the right superior temporal gyrus of those with IGD, compared with the alcohol use disorder and healthy controls group. Scores on internet addiction severity were positively correlated with ReHo in the medial frontal cortex, precuneus/PCC, and left inferior temporal cortex among those with IGD.

3.4. Fasting

Belaich et al. [13] assessed the effect of daytime fasting on six healthy male volunteers during Ramadan. Two task-based BOLD-fMRI scan sessions were performed, the first scan between the fifth and tenth days preceding the start of fasting and the second scan between the 25th and 28th day of the fasting month. The study demonstrated a significant difference in the activated brain area between maximal BOLD-fMRI signal before and during fasting. In addition, there was an increase in the volume of the activated brain area in all subjects during fasting.

3.5. Physical training

There were five interventional and two observational studies that looked at the effect of physical training on brain health in midlife, as expressed on fMRI. Chapman et al. [15] assessed brain-blood flow in 37 sedentary adults, in a clinical control trial of physical training versus a wait-list control group. Over 12 weeks, the physical training group received supervised aerobic exercise for three 1-hour sessions per week. The study found higher resting CBF in the anterior cingulate region in the physical training group as compared with the control group from baseline to post-training. In a follow-up randomized control study, Chapman et al. [17] compared the effects of two training protocols, cognitive training and physical training on brain function. The study indicates that increased cognitive and physical activities improve brain health in distinct ways. Aerobic exercise improved CBF flow in hippocampi of those with memory gains.

MacIntosh et al. [30] assessed 30 men with coronary artery disease, before and after a 6-month cardiac rehabilitation program consisting of aerobic and resistance training. CBF was associated with fitness level at baseline and greater fitness gains with exercise. McFadden et al. [32] assessed the effects of a 6-month exercise intervention on intrinsic activity in the DMN in 12 overweight or obese individuals. The intervention was associated with a reduction in DMN activity in the precuneus. This finding is thought to represent a normalization of DMN function secondary to exercise.

In a controlled clinical trial, Hotting et al. [22] assessed the effects of cognitive training (spatial vs. perceptual training) and physical training (endurance training vs. nonendurance training) on spatial learning and associated brain activation in 33 adults. Spatial learning was assessed with a virtual maze task and at the same time neural correlates were measured with fMRI. The two physical intervention groups did not improve performance in the maze task.

The findings of the two observational studies related to physical training focused on specific population groups. Hart el al. [20]. assessed aging former National Football League (NFL) players. They found that cognitive deficits and depression appear to be more common in ageing former NFL players than healthy controls. In addition, altered CBF patterns are concordant with brain regions associated with abnormal findings of neuropsychological testing in ageing former NFL players. It is noteworthy that of the 34 ex-NFL players included in the study, 32 reported a history of at least one concussion and 26 undertook neuroimaging; eight were claustrophobic and did not undergo an MRI scan. In a cross-sectional study of 59 adults recruited through a Rhode Island newspapers and an outpatient cardiology office, Xu et al. [40] found that women who engaged in strength training (weight lifting or calisthenics) at least once per week exhibited significantly greater cerebrovascular perfusion than women who did not.

3.6. Smoking

There were three cross-sectional studies identified in this systematic review that assessed the effect of smoking on brain health as expressed on fMRI. Durazzo et al. [18] investigated the chronic effects of smoking on brain perfusion. Smokers showed significantly lower perfusion than nonsmokers in multiple brain regions (bilateral medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortices, bilateral inferior parietal lobules, bilateral superior temporal gyri, left posterior cingulate, right isthmus of cingulate, and right supramarginal gyrus) as assessed on fMRI. In addition, greater lifetime duration of smoking (adjusted for age) was related to lower perfusion in multiple brain regions. Gazdzinski et al. [19] assessed 1 week abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals in treatment (19 smokers and 10 nonsmokers) and 19 healthy light drinking nonsmoking control participants, to assess the concurrent effects of chronic alcohol and chronic smoking on cerebral perfusion. This study found that chronic cigarette smoking adversely affects cerebral perfusion in frontal and parietal gray matter of 1 week abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Mon et al. [44] evaluated cortical gray matter perfusion changes in short-term abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals in treatment and assessed the impact of chronic cigarette smoking on perfusion changes during abstinence. At 1 week of abstinence, frontal and parietal gray matter perfusion in smoking alcoholics was not significantly different from that in nonsmoking alcoholics. After 5 weeks of abstinence, perfusion of frontal and parietal gray matter in nonsmoking alcoholics was significantly higher than that at baseline. However, in smoking alcoholics, perfusion was not significantly different. Cigarette smoking appears to hinder perfusion improvement in abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals.

3.7. Substance misuse

Of the 12 cross-sectional studies assessing the relationship between substance misuse and neurodegeneration, nine of the studies focused on the effect of cocaine, one on heroin, one on methamphetamine, and one on polysubstance misuse.

The five task-based fMRI studies that looked at the effect of cocaine used many different fMRI measures to assess brain health, making it difficult to compare the research findings. Of the four resting-state fMRI studies assessing the effect of cocaine on brain health, both Hu et al. [23] and Kelly et al. [26] assessed the resting-state functional connectivity. Hu et al. [23] found that cocaine addiction is associated with disturbed resting-state functional connectivity in striatal-cortical circuits. Kelly et al. [26] observed reduced prefrontal interhemispheric resting-state functional connectivity in cocaine-dependent participants relative to control subjects. Liu et al. [29] used cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) as a marker of neural activity and found significantly lower levels in cocaine-addicted subjects compared with healthy controls. In a multimodal MRI study, Wang et al. [38] identified hypoperfusion in the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, right temporal cortex, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in cocaine addicts compared with controls.

Other than the nine studies focusing on cocaine and neurodegeneration, there were three more cross-sectional studies (one on heroin, one on methamphetamine, and one on polysubstance misuse) identified in the systematic review focusing on substance misuse. Jiang et al. [25] investigated amplitude low frequency fluctuate abnormalities in heroin users. Comparing healthy controls and heroin addicts, this resting-state fMRI study found differing spontaneous neural activity patterns in multiple regions, in the heroin addict group. Heroin addicts had decreased amplitude low frequency fluctuate in the bilateral dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, bilateral medial orbit frontal cortex, left dorsal lateral prefrontal cortex, left middle temporal gyrus, left inferior temporal gyrus, PCC, and left cuneus as well as increased amplitude low frequency fluctuate in the bilateral angular gyrus, bilateral precuneus, bilateral supramarginal gyrus, left post cingulate cortex and left middle frontal gyrus. Using a task-based fMRI protocol, May et al. [31] found that methamphetamine-dependent individuals exhibited altered responses to mechanoreceptive C-fiber stimulation in brain regions important for interoception. Murray et al [35] assessed brain perfusion in polysubstance users. They found that the combination of cigarette smoking and polysubstance use is strongly related to hypoperfusion in cortical and subcortical regions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

This systematic review identified seven lifestyle factors—physical training, cognitive training, fasting, substance misuse, alcohol, smoking, and excessive internet use—which had been researched, assessing their impact on neurodegeneration in midlife as expressed on fMRI.

4.2. Comparison with other literature

In late life, the impact of lifestyle factors on brain health has already been studied in multimodal nonpharmacological interventional studies such as the Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability [45]. The findings from this double-blind randomized control trial suggest that a 2-year multidomain intervention that included diet, exercise, and cognitive training could maintain or even improve cognitive functioning in an elderly population. In midlife, gathering evidence on the interplay between lifestyle and a broad range of markers of brain health is ongoing in projects such as the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia Longitudinal Cohort Study [46]. The study is aiming to develop a well-phenotyped probability spectrum population for Alzheimer's dementia. More specifically, data on lifestyle factors and neurodegeneration in midlife as expressed on fMRI are currently being collected in the PREVENT Dementia study [2]. This is a prospective cohort study to identify midlife biomarkers of the late-onset Alzheimer's disease. The European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia Longitudinal Cohort Study [46] and PREVENT Dementia studies [2] are yet to report on the relationship between lifestyle factors and neurodegeneration in midlife.

4.3. Strengths and limitations

This systematic review used a robust methodology, including a comprehensive search strategy with search terms tailored to each database examined in the review. In addition, all stages of article screening and quality assessment were undertaken independently by two reviewers. However, the systematic review has a number of limitations: There was a marked inconsistency in both study design and methodology of the included studies, which limits the confidence in our conclusions. Study populations with different demographics were assessed, different fMRI protocols were used by the studies (18 task-based and 11 resting-state), different statistical approaches to analyze the data and different fMRI outcome measures all added to this inconsistency. In addition, caution is necessary when interpreting fMRI outcome measures and how they relate to underlying neural activity. More studies are needed to provide a firmer understanding of situations when fMRI outcome measures and neural activity are coupled and when they dissociate [47].

4.4. Implications

This systematic review will contribute to our endeavor to gain a better understanding of what lifestyle factors could be reduced or enhanced to help optimize brain health in midlife and therein reduce an individual's risk of later life dementia. More specifically, the information retrieved by this systematic review could give guidance on the analysis of existing lifestyle and fMRI data in dementia prevention longitudinal cohort studies such as the PREVENT Dementia study [2]. In addition, it could help shape future multimodal nonpharmacological midlife dementia prevention studies.

4.5. Conclusions

From this systematic review, common themes have emerged on the effect of lifestyle on brain health in midlife as expressed on fMRI. All the cognitive training studies showed what could be considered a neuroprotective effect, whereas all the alcohol, smoking, and substance misuse studies showed an effect that could reflect neurodegeneration. Studies on physical training showed more variation in results. Most physical training studies showed a potential neuroprotective effect, and one study showed no effect. One study described a possible neurodegenerative effect associated with physical training; in this study by Hart et al. 2013 [20], the majority of the ex-NFL players assessed had a history of concussion. The evidence from studies on the effects of excessive internet use and fasting on brain health in midlife is too limited to allow any conclusions to be drawn.

Overall, this systematic review of the relationship between lifestyle factors and neurodegeneration in midlife as expressed on fMRI provides an evidence base for further lifestyle and fMRI research to build upon. Projects such as the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia [46] and PREVENT Dementia [2] have the potential to do this and continue our drive toward the goal of reducing the global incidence of dementia.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: The authors searched the following literature databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO. Articles were screened, and quality was assessed independently by two reviewers. The identified studies were then individually described and grouped by lifestyle factor.

-

2.

Interpretation: The systematic review identified seven lifestyle factors (physical training, cognitive training, fasting, substance misuse, alcohol, smoking, and excessive internet use) associated with brain health in midlife as expressed on fMRI. Physical training and cognitive training have a possible neuroprotective effect. Substance misuse, alcohol, and smoking have a likely neurodegenerative effect.

-

3.

Future directions: More research is needed into the possible neuroprotective effect of abstaining from smoking, alcohol and substance misuse, and engaging in physical and cognitive training on brain health in midlife. In addition, studies are needed to clarify the effects of fasting and excessive internet use on fMRI outcomes in midlife.

Acknowledgments

Professor Adam Waldman, Chair of Neuroradiology, Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh provided advice on fMRI techniques.

Funding: This work was supported by the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement number 115736, resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies' in kind contribution.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trci.2018.04.001.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Ritchie K., Ritchie C.W., Yaffe K., Skoog I., Scarmeas N. Is late-onset Alzheimer's disease really a disease of midlife? Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2015;1:122–130. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritchie C.W., Ritchie K. The PREVENT study: a prospective cohort study to identify mid-life biomarkers of late-onset Alzheimer's disease. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001893. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickerson B.C. Humana Press; New York, NY: 2009. FMRI in Neurodegenerative Diseases: from Scientific Insights to Clinical Applications; pp. 657–680.https://link.springer.com/protocol/10.1007%2F978-1-4939-5611-1_23#citeas fMRI Techniques and Protocols. Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulz J., Deuschl G. Influence of lifestyle on neurodegenerative diseases. Der Nervenarzt. 2015;86:954–959. doi: 10.1007/s00115-014-4252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Przedborski S., Vila M., Jackson-Lewis V. Series introduction: neurodegeneration: what is it and where are we? J Clin Invest. 2003;111:3–10. doi: 10.1172/JCI17522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vajda F.J.E. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2004. Neuroprotection and Neurodegenerative Disease; pp. 235–243. Alzheimer’s Disease: Springer. Available at: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-59259-661-4_27. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nutbeam D. Health promotion glossary. Health Promot Int. 1998;13:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noll D.C. University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, Michigan: 2001. A Primer on MRI and Functional MRI. Technical Raport. Available at: http://www.eecs.umich.edu/ dnoll/primer2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKhann G., Drachman D., Folstein M., Katzman R., Price D., Stadlan E.M. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group* under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas B.H., Ciliska D., Dobbins M., Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deeks J.J., Dinnes J., D'Amico R., Sowden A.J., Sakarovitch C., Song F. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:1–173. doi: 10.3310/hta7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bednarski S.R., Zhang S., Hong K.I., Sinha R., Rounsaville B.J., Li C.S. Deficits in default mode network activity preceding error in cocaine dependent individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;119:e51–e57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belaich R., Boujraf S., Benzagmout M., Magoul R., Maaroufi M., Tizniti S. Implications of oxidative stress in the brain plasticity originated by fasting: a BOLD-fMRI study. Nutr Neurosci. 2017;20:505–512. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2016.1191165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castelluccio B.C., Meda S.A., Muska C.E., Stevens M.C., Pearlson G.D. Error processing in current and former cocaine users. Brain Imaging Behav. 2014;8:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s11682-013-9247-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chapman S.B., Aslan S., Spence J.S., DeFina L.F., Keebler M.W., Didehbani N. Shorter term aerobic exercise improves brain, cognition, and cardiovascular fitness in aging. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:75. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chapman S.B., Aslan S., Spence J.S., Hart J.J., Jr., Bartz E.K., Didehbani N. Neural mechanisms of brain plasticity with complex cognitive training in healthy seniors. Cereb Cortex. 2015;25:396–405. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapman S.B., Aslan S., Spence J.S., Keebler M.W., DeFina L.F., Didehbani N. Distinct brain and behavioral benefits from cognitive vs. Physical training: a randomized trial in aging adults. Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:338. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durazzo T.C., Meyerhoff D.J., Murray D.E. Comparison of regional brain perfusion levels in chronically smoking and non-smoking adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:8198–8213. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120708198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gazdzinski S., Durazzo T., Jahng G.H., Ezekiel F., Banys P., Meyerhoff D. Effects of chronic alcohol dependence and chronic cigarette smoking on cerebral perfusion: a preliminary magnetic resonance study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:947–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart J., Jr., Kraut M.A., Womack K.B., Strain J., Didehbani N., Bartz E. Neuroimaging of cognitive dysfunction and depression in aging retired National Football League players: a cross-sectional study. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:326–335. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamaneurol.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermann D., Smolka M.N., Klein S., Heinz A., Mann K., Braus D.F. Reduced fMRI activation of an occipital area in recently detoxified alcohol-dependent patients in a visual and acoustic stimulation paradigm. Addict Biol. 2007;12:117–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2006.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hotting K., Holzschneider K., Stenzel A., Wolbers T., Roder B. Effects of a cognitive training on spatial learning and associated functional brain activations. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:73. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu Y., Salmeron B.J., Gu H., Stein E.A., Yang Y. Impaired functional connectivity within and between frontostriatal circuits and its association with compulsive drug use and trait impulsivity in cocaine addiction. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:584–592. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ide J.S., Hu S., Zhang S., Mujica-Parodi L.R., Li C.S.R. Power spectrum scale invariance as a neural marker of cocaine misuse and altered cognitive control. Neuroimage. 2016;11:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiang G.H., Qiu Y.W., Zhang X.L., Han L.J., Lv X.F., Li L.M. Amplitude low-frequency oscillation abnormalities in the heroin users: a resting state fMRI study. Neuroimage. 2011;57:149–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly C., Zuo X.N., Gotimer K., Cox C.L., Lynch L., Brock D. Reduced interhemispheric resting state functional connectivity in cocaine addiction. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:684–692. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim H., Kim Y.K., Gwak A.R., Lim J.-A., Lee J.-Y., Jung H.Y. Resting-state regional homogeneity as a biological marker for patients with internet gaming disorder: A comparison with patients with alcohol use disorder and healthy controls. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2015;60:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J.H., Telang F.W., Springer C.S., Jr., Volkow N.D. Abnormal brain activation to visual stimulation in cocaine abusers. Life Sci. 2003;73:1953–1961. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu P., Lu H., Filbey F.M., Tamminga C.A., Cao Y., Adinoff B. MRI assessment of cerebral oxygen metabolism in cocaine-addicted individuals: hypoactivity and dose dependence. NMR Biomed. 2014;27:726–732. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacIntosh B.J., Swardfager W., Crane D.E., Ranepura N., Saleem M., Oh P.I. Cardiopulmonary fitness correlates with regional cerebral grey matter perfusion and density in men with coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91251. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.May A.C., Stewart J.L., Migliorini R., Tapert S.F., Paulus M.P. Methamphetamine dependent individuals show attenuated brain response to pleasant interoceptive stimuli. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McFadden K.L., Cornier M.A., Melanson E.L., Bechtell J.L., Tregellas J.R. Effects of exercise on resting-state default mode and salience network activity in overweight/obese adults. Neuroreport. 2013;24:866–871. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell M.R., Balodis I.M., Devito E.E., Lacadie C.M., Yeston J., Scheinost D. A preliminary investigation of Stroop-related intrinsic connectivity in cocaine dependence: associations with treatment outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39:392–402. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.841711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mon A., Durazzo T.C., Gazdzinski S., Meyerhoff D.J. The impact of chronic cigarette smoking on recovery from cortical gray matter perfusion deficits in alcohol dependence: longitudinal arterial spin labeling MRI. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1314–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray D.E., Durazzo T.C., Mon A., Schmidt T.P., Meyerhoff D.J. Brain perfusion in polysubstance users: relationship to substance and tobacco use, cognition, and self-regulation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;150:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers B.P., Parks M.H., Nickel M.K., Katwal S.B., Martin P.R. Reduced fronto-cerebellar functional connectivity in chronic alcoholic patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan E.V., Muller-Oehring E., Pitel A.L., Chanraud S., Shankaranarayanan A., Alsop D.C. A selective insular perfusion deficit contributes to compromised salience network connectivity in recovering alcoholic men. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:547–555. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z., Suh J., Duan D., Darnley S., Jing Y., Zhang J. A hypo-status in drug-dependent brain revealed by multi-modal MRI. Addict Biol. 2017;22:1622–1631. doi: 10.1111/adb.12459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weiland B.J., Sabbineni A., Calhoun V.D., Welsh R.C., Bryan A.D., Jung R.E. Reduced left executive control network functional connectivity is associated with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:2445–2453. doi: 10.1111/acer.12505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu X., Jerskey B.A., Cote D.M., Walsh E.G., Hassenstab J.J., Ladino M.E. Cerebrovascular perfusion among older adults is moderated by strength training and gender. Neurosci Lett. 2014;560:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hermann D., Smolka M.N., Wrase J., Klein S., Nikitopoulos J., Georgi A. Blockade of cue-induced brain activation of abstinent alcoholics by a single administration of amisulpride as measured with fMRI. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1349–1354. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Association AP . American Psychiatric Association Publishing; Washington, D.C.: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) Available at: https://psychiatryonline.org/contact. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young K.S. Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the Internet: a case that breaks the stereotype. Psychol Rep. 1996;79:899–902. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1996.79.3.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mon A., Gazdzinski S., Durazzo T.C., Meyerhoff D.J. Long-term brain perfusion recovery patterns in abstinent non-smoking and smoking alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:226A. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kivipelto M., Solomon A., Ahtiluoto S., Ngandu T., Lehtisalo J., Antikainen R. The Finnish geriatric intervention study to prevent cognitive impairment and disability (FINGER): study design and progress. Alzheimer's Demen. 2013;9:657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ritchie C.W., Molinuevo J.L., Truyen L., Satlin A., Van der Geyten S., Lovestone S. Development of interventions for the secondary prevention of Alzheimer's dementia: the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia (EPAD) project. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:179–186. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00454-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ekstrom A. How and when the fMRI BOLD signal relates to underlying neural activity: the danger in dissociation. Brain Res Rev. 2010;62:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.