Abstract

Introduction

Treatments for Alzheimer's disease (AD) are needed due to the growing number of individuals with preclinical, prodromal, and dementia forms of AD. Drug development for AD therapies can be examined by inspecting the drug development pipeline as represented on clinicaltrials.gov.

Methods

Clinicaltrials.gov was assessed as of January 30, 2018 to determine AD therapies represented in phase I, phase II, and phase III.

Results

There are 112 agents in the current AD treatment pipeline. There are 26 agents in 35 trials in phase III, 63 agents in 75 trials in phase II, and 23 agents in 25 trials in phase I. A review of the mechanisms of actions of the agents in the pipeline shows that 63% are disease-modifying therapies, 22% are symptomatic cognitive enhancers, and 12% are symptomatic agents addressing neuropsychiatric and behavioral changes. Trials in phase III are larger and longer than phase II or phase I trials, particularly those involving disease-modifying agents. Comparison with the 2017 pipeline shows that there are four new agents in phase III, 14 in phase II, and eight in phase I. Inspection of the use of biomarkers as revealed on clinicaltrials.gov shows that amyloid biomarkers are used as entry criterion in 14 phase III disease-modifying agent trials and 17 disease-modifying agent trials in phase II. Twenty-one trials of disease-modifying agents in phase II did not require biomarker confirmation for AD at trial entry.

Discussion

The AD drug development pipeline is slightly larger in 2018 than in 2017. Trials increasingly include preclinical and prodromal populations. There is an increase in nonamyloid mechanisms of action for drugs in earlier phases of drug development. Biomarkers are increasingly used in AD drug development but are not used uniformly for AD diagnosis confirmation.

Keywords: Alzheimer's, Pipeline, Clinicaltrials.gov, Biomarkers, Drug development, Clinical trials, Monoclonal antibodies, Amyloid, Tau, Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2018

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder with cognitive, functional, and behavioral alterations [1], [2]. AD is age related and is becoming markedly more common with the aging of the world's population. It is estimated that by 2050, one in every 85 people will be living with AD [3]. Nearly eightfold as many people have preclinical AD as have symptomatic AD and are at risk for progressing to manifest disease [4]. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) that will prevent or delay the onset or slow the progression of AD are urgently needed. A modest 1-year delay in onset by 2020 would result in there being 9.2 million fewer cases in 2050 [3]. Similarly, medications to effectively improve cognition or ameliorate neuropsychiatric symptoms of patients in the symptomatic phases of AD are needed to improve memory and behavior [5].

In this update of our annual review of the AD drug development pipeline, we provide a summary of the current state of progress in developing new therapies for AD [6], [7]. We discuss each phase of the AD pipeline (I, II, and III) and describe DMTs, cognitive-enhancing agents, and treatments for behavioral disturbances in AD that are in development. We note the use of biomarkers in clinical trials. We describe evolving targets of the agents in the pipeline. We discuss trial infrastructure changes that may accelerate clinical trials and drug development. Our goal is to provide insight into the drug development process and to help drug developers and clinical trialists learn from the current pipeline experience.

2. Methods

This annual review is based on clinical trial activity as recorded in clinicaltrials.gov, a comprehensive US government database. The US law requires that all clinical trials conducted in the United States be registered on the site. The “common rule” governing clinicaltrials.gov was recently updated and mandated registration of all trials from sponsors with an Investigational New Drug or Investigational New Device [8], [9]. Trials must be registered within 21 days of the enrollment of the first trial participant. Results for the primary outcome measures must be submitted to clincaltrials.gov within 12 months of completion of final data collection. Compliance with trial registration is high [10], [11], [12]; compliance with results reporting is lower [13]. Clinicaltrials.gov can be regarded as a comprehensive and valid data source for the study of clinical trials conducted in the United States. Not all non-US trials are registered on clinicaltrials.gov—especially phase I trials—and our findings may underrepresent the agents populating global phase I efforts.

Results reported here are based on trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov as of January 30, 2018. We include all trials of all agents in phase I, II, and III; some trials are presented as I/II or II/III in the database, and we use that nomenclature in the review. In our trial database, we entered the trial title; beginning date; projected end date; calculated duration; planned enrollment number; number of arms of the study (usually a placebo arm and one or more treatment arms with different doses); whether a biomarker was described; subject characteristics; and sponsorship by a biopharma company, National Institutes of Health, academic medical center, “other” entity such as a consortium or a philanthropic organization, or a combination of these sponsors. Using the clinicaltrials.gov classification, we included trials that were recruiting, active but not recruiting (e.g., trials that have completed recruiting and are continuing with the exposure portion of the trial), enrolling by invitation, and not yet recruiting. We did not include trials listed as completed, terminated, suspended, unknown, or withdrawn because information on these trials is often incomplete. We included all pharmacologic trials listed in the database; we did not include trials of nonpharmacologic therapeutic approaches such as devices, cognitive therapies, caregiver interventions, supplements, and medical foods. We did not include trials of biomarkers although we noted whether biomarkers were used in the trials of interest.

Drug targets and mechanism of action (MOA) of treatments are important aspects of this review. MOA was determined from the information on clinicaltrials.gov or from a comprehensive search of the literature. In a few cases, the mechanism is undisclosed and could not be identified in the literature, and we note these agents as having an “unknown” MOA. We grouped the mechanisms into symptomatic agents or DMTs. We divided the symptomatic agents into those that are putative cognitive-enhancing agents or those that address neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms. DMTs were divided into those targeting amyloid-related mechanisms, those that have tau-related MOAs, and those with “other” mechanisms such as neuroprotective agents, anti-inflammatory drugs, growth factors, or agents with metabolic effects. Stem cell therapies were included in the “other” category. Some agents have multiple effects and might be expected to have symptomatic and disease-modifying properties. We classified these drugs as symptomatic or DMTs based on the trial design. Agents in large, long (12–24 months) trials with biomarker outcomes are listed as DMTs. Those in smaller, shorter (3–6 months) trials with cognitive or behavioral outcomes and no biomarkers are listed as symptomatic. Agents could change classification as more information accrues.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

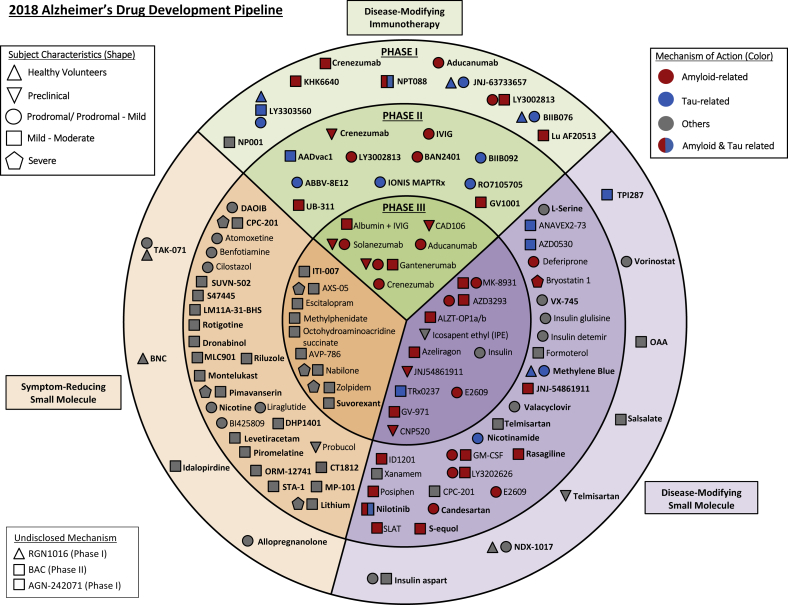

Fig. 1 provides an overview of all agents identified in the current AD pipeline. The main circles of the figure reveal the stage of development (I, II, and III), the colors pertain to the MOA of the agent, and the shape denotes the population in which the agent is being tested (normal volunteers, cognitively normal at-risk individuals, prodromal AD, and AD dementia).

Fig. 1.

Agents in clinical trials for treatment of Alzheimer's disease in 2018 (from clinicaltrials.gov accessed January 30, 2018).

In total, there are 112 agents in the pipeline as shown on clinicaltrials.gov. We identified 26 agents in 35 trials in phase III, 63 agents in 75 trials in phase II, and 23 agents in 25 trials in phase I. Review of the MOAs of pipeline agents showed that 63% are DMTs, 22% are symptomatic cognitive enhancers, 12% are symptomatic agents addressing neuropsychiatric and behavioral changes, and 3% have undisclosed MOAs.

3.2. Phase III

Phase III of the 2018 AD pipeline has 26 agents; 17 DMTs, one cognitive-enhancing agent, and eight drugs for behavioral symptoms (Fig. 1, Table 1). Among the DMTs, 14 addressed amyloid targets, one involved a tau-related target, one involved neuroprotection, and one had a metabolic MOA. The DMTs include six immunotherapies (all addressing amyloid). Of the DMTs, two are repurposed agents approved for use in another indication (insulin, albumin plus immunoglobulin). Of the drugs with amyloid targets, there were five Beta-site Amyloid precursor protein Cleavage Enzyme inhibitors, six immunotherapies, and three antiaggregation agents. Fig. 2 shows the MOAs of agents in phase III.

Table 1.

Agents currently in phase III of Alzheimer's disease drug development (as of January 30, 2018)

| Agent | Agent mechanism class | Mechanism of action | Therapeutic purpose | Clinicaltrials.gov ID | Status | Sponsor | Start date | Estimated end date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aducanumab | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT02484547 | Recruiting | Biogen | September-15 | April-22 |

| NCT02477800 | Recruiting | Biogen | August-15 | March-22 | ||||

| Albumin + immunoglobulin | Anti-amyloid | Polyclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT01561053∗ | Active, not recruiting | Grifols | March-12 | December-17 |

| ALZT-OP1a + ALZT-OP1b (cromolyn + ibuprofen) | Anti-amyloid, anti-inflammatory | Mast cell stabilizer (cromolyn), anti-inflammatory (ibuprofen) | Reduce neuronal damage; mast cells may also play a role in amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT02547818 | Recruiting | AZTherapies, Pharma Consulting Group, KCAS Bio, APCER Life Sciences | September-15 | November-19 |

| AVP-786 | Neurotransmitter based | Sigma 1 receptor agonist; NMDA receptor antagonist | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT02442765 | Recruiting | Avanir | September-15 | July-18 |

| NCT02446132 | Recruiting-EXT | Avanir | December-15 | March-21 | ||||

| AZD3293 (LY3314814) | Anti-amyloid | BACE1 inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT02245737∗ | Active, not recruiting | AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly | September-14 | September-19 |

| NCT02783573 | Recruiting | AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly | July-16 | March-21 | ||||

| NCT02972658 | Recruiting-EXT | AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly | March-17 | September-20 | ||||

| AXS-05 | Neurotransmitter based | Sigma 1 receptor agonist; NMDA receptor antagonist (dextromethorphan); serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibition (bupropion) | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT03226522 | Recruiting | Axsome Therapeutics | July-17 | September-19 |

| CAD106 & CNP520 | Anti-amyloid | Amyloid vaccine, BACE inhibitor | Remove/reduce amyloid (DMT) | NCT02565511∗ | Recruiting | Novartis, Amgen, NIA, Alzheimer's Association, Banner Alzheimer's Institute | November-15 | May-24 |

| CNP520 | Anti-amyloid | BACE Inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT03131453 | Recruiting | Novartis, Amgen, Banner Alzheimer's Institute | August-17 | July-24 |

| Crenezumab | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT02670083 | Active, not recruiting | Roche/Genentech | March-16 | July-21 |

| NCT03114657 | Recruiting | Roche/Genentech | March-17 | October-22 | ||||

| E2609 (elenbecestat) | Anti-amyloid | BACE inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT02956486 | Recruiting | Eisai, Biogen | October-16 | December-20 |

| NCT03036280 | Recruiting | Eisai, Biogen | December-16 | December-20 | ||||

| Escitalopram | Neurotransmitter based | Serotonin reuptake inhibition | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT03108846 | Not yet recruiting | NIA, JHSPH Center for Clinical Trials | September-17 | March-21 |

| Gantenerumab | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT02051608 | Active, not recruiting | Roche | March-14 | November-19 |

| NCT01224106 | Active, not recruiting | Roche | November-10 | July-20 | ||||

| Gantenerumab and solanezumab and JNJ-54861911 | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody, BACE inhibitor | Remove amyloid/reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT01760005∗ | Recruiting | Washington University, Eli Lilly, Roche, NIA, Alzheimer's Association | December-12 | December-23 |

| Icosapent ethyl (IPE) | Neuroprotective | Purified form of the omega-3 fatty acid EPA | Protect neurons from disease pathology | NCT02719327∗ | Recruiting | VA Office of Research and Development, University of Wisconsin, Madison | December-16 | November-21 |

| Insulin intranasal (Humulin) | Metabolic | Replace insulin in the brain | Enhance cell signaling and neurogenesis (cognitive enhancer) | NCT01767909∗ | Active, not recruiting | University of Southern California, NIA, ATRI, Wake Forest University | January-14 | December-18 |

| ITI-007 | Neurotransmitter based | 5-HT2A antagonist, dopamine receptor modulator | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT02817906 | Recruiting | Intra-Cellular Therapies, Inc. | June-16 | August-18 |

| JNJ-54861911 | Anti-amyloid | BACE inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT02569398∗ | Recruiting | Janssen | November-15 | April-24 |

| Methylphenidate | Neurotransmitter based | Dopamine reuptake inhibitor | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (apathy) | NCT02346201 | Recruiting | Johns Hopkins, NIA | January-16 | August-20 |

| MK-8931 (verubecestat) | Anti-amyloid | BACE inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT01953601 | Active, not recruiting | Merck | November-13 | March-21 |

| MK-4305 (suvorexant) | Neurotransmitter based | Dual orexin receptor antagonist | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (sleep disorders) | NCT02750306 | Recruiting | Merck | May-16 | April-18 |

| Nabilone | Neurotransmitter based | Cannabinoid (receptor agent) | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT02351882∗ | Recruiting | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | January-15 | January-18 |

| Octohydroaminoacridine succinate | Neurotransmitter based | Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor | Improve acetylcholine signaling (cognitive enhancer) | NCT03283059 | Recruiting | Shanghai Mental Health Center, Changchun-Huayang High-tech Co., Jiangsu Sheneryang High-tech Co. | August-17 | February-20 |

| GV-971 (Sodium Oligo-mannurarate) | Anti-amyloid | Inhibit amyloid aggregation | Remove amyloid plaque load (DMT) | NCT02293915 | Recruiting | Shanghai Green valley Pharmaceutical | April-14 | September-18 |

| Solanezumab | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT02008357 | Active, not recruiting | Eli Lilly, ATRI | February-14 | July-22 |

| TRx0237 (LMTX) | Anti-tau | Tau protein aggregation inhibitor | Reduce tau-mediated neuronal damager (DMT) | NCT02245568 | Recruiting, Extension | TauRx Therapeutics | August-14 | September-17 |

| TTP488 (azeliragon) | Anti-amyloid, anti-inflammatory | RAGE antagonist | Reduce amyloid uptake in brain and lower inflammation in glial cells (DMT/cognitive enhancer) | NCT02080364 | Active, not recruiting | vTv Therapeutics | April-15 | January-19 |

| NCT02916056 | Recruiting – EXT | December-16 | November-20 | |||||

| Zolpidem | Neurotransmitter based | Positive allosteric modulator of GABA-A receptors | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (sleep disorders) | NCT03075241 | Recruiting | Brasilia University Hospital | October-16 | December-18 |

Abbreviations: ATRI, Alzheimer's Therapeutic Research Institute; BACE, Beta-site Amyloid precursor protein Cleaving Enzyme; DMT, disease-modifying therapy; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; NIA, National Institute on Aging; RAGE, receptor for advanced glycation end products.

NOTE. Twenty-six agents in 35 phase III clinical trials currently ongoing as of January 30, 2018 according to clinicaltrials.gov.

NOTE. Bolded terms represent new entries into the 2018 phase III pipeline.

Phase II/III trials.

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of action of agents in phase III.

There is a movement toward treating patients with milder forms of AD including cognitively normal individuals with evidence of amyloid pathology (by cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] measures or amyloid positron emission tomography [PET]) or who have genetic profiles that place them at high risk for developing AD (Table 2). In phase III, there were six prevention trials enrolling cognitively normal participants. There were 12 trials of patients with prodromal AD/mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or prodromal/mild AD; 14 trials of patients with mild-moderate AD; and three trials of patients with mild-moderate/severe AD.

Table 2.

Prevention trial by phase

| Phase | Agent | Trial | Sponsor | Means of defining risk for AD dementia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| III | Solanezumab | A4 | Eli Lilly | Amyloid PET |

| II/III | CAD106, CNP520 | Generation S1 | Novartis | Homozygous APOE4 |

| II/III | CNP520 | Generation S2 | Novartis | Amyloid PET or CSF |

| II/III | Icosapent ethyl (IPE) | BRAVE-EPA | VA Office of Research and Development | Parental history of AD and increased prevalence of APOE4 allele |

| II/III | JNJ-54861911 | Early | Janssen | Amyloid PET or CSF |

| II/III | Gantenerumab, solanezumab, JNJ-54861911 | DIAN-TU | Eli Lilly, Roche, Janssen, NIA | Family history of autosomal dominant AD |

| II | Crenezumab | GN28352 | Genentech | Presenilin-1 E280 A mutation |

| I/II | Probucol | DEPEND | Douglas Mental Health University | Family history of AD |

| I | Telmisartan | HEART | Emory University | Parental history of AD |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE, apolipoprotein E; BRAVE-EPA, Brain Amyloid and Vascular Effects of Eicosapontaenoic Acid; DEPEND, Dosage and Etiology of Protocols Induced apoE to Negate Cognitive Deterioration; DIAN-TU, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network-Treatment Unit; HEART, Health Evaluation of African Americans Using RAS Therapy; NIA, National Institute on Aging; PET, positron emission tomography.

Phase III trials involved a mean of 860 participants and had a mean duration of 1841 days or 263 weeks (including the recruitment and the treatment period). DMT trials were longer than trials of agents with other MOAs (2139 days or 306 weeks; 121 treatment weeks) and larger—including an average of 1066 participants. The mean duration of cognitive enhancer trials was 914 days or 131 weeks (26 treatment weeks), and they included an average of 600 participants. Trials of drugs for behavioral symptoms average 1119 days or 160 weeks (15 treatment weeks) and included a mean of 314 patients. For DMTs, the average duration of treatment exposure is 121 weeks; the mean period from trial initiation to primary completion date (final data collection date for primary outcome measure) is 239 weeks. This indicates that 118 weeks—nearly equal to the treatment period—is the average anticipated recruitment time. When examined by trial population, prevention trials are 420 weeks in duration; trials for patients with MCI/prodromal/prodromal-mild AD are 289 weeks in duration; and trials for patients mild-moderate AD are 235 weeks in duration. Planned recruitment periods for these three types of trials are 164, 161, and 116 weeks, respectively.

3.3. Phase II

In 2018, there are 75 trials involving 63 agents in phase II of the AD pipeline (Table 3). Sixteen trials involved patients with prodromal or prodromal and mild AD, 28 were trials for mild-moderate AD, one included patients with MCI and mild-moderate AD, one was a prevention trial, one included patients with MCI or healthy volunteers, and one trial was for severe AD. Of the symptomatic agent trials, one was for preclinical AD, seven were for prodromal mild AD, 16 were for mild-moderate AD, and three were for mild-moderate or severe AD.

Table 3.

Agents currently in phase II of Alzheimer's disease drug development (as of January 30, 2018)

| Agent | Agent mechanism class | Mechanism of action | Therapeutic purpose | Clinicaltrials.gov ID | Status | Sponsor | Start date | Estimated end date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AADvac1 | Anti-tau | Active immunotherapy | Remove tau (DMT) | NCT02579252 | Active, not recruiting | Axon Neuroscience | March-16 | June-19 |

| ABBV-8E12 | Anti-tau | Monoclonal antibody | Remove tau (DMT) | NCT02880956 | Recruiting | AbbVie | October-16 | June-21 |

| ANAVEX 2-73 | Anti-tau, metabolic | Sigma-1 receptor agonist (high affinity); muscarinic agonist (low affinity); GSK-3β inhibitor | Improve cell signaling (cognitive enhancer) and reduce tau phosphorylation (DMT) | NCT02244541 | Active, not recruiting | Anavex Life Sciences | December-14 | October-16 |

| NCT02756858 | Recruiting, extension | Anavex Life Sciences | March-16 | November-18 | ||||

| AstroStem | Regenerative | Autologous adipose tissue derived mesenchymal stem cells | Regenerate neurons | NCT03117738 | Recruiting | Nature Cell Co. | April-17 | November-18 |

| Atomoxetine | Neurotransmitter based | Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor | Improve neurotransmission (cognitive enhancer) and improve behavioral symptoms | NCT01522404 | Active, not recruiting | Emory University, NIA | March-12 | June-18 |

| AZD0530 (saracatinib) | Metabolic, anti-tau | Tyrosine kinase Fyn inhibitor | Improve synaptic dysfunction (cognitive enhancer), reduce tau phosphorylation (DMT) | NCT02167256 | Active, not recruiting | Yale University, ATRI, AstraZeneca | December-14 | December-17 |

| BAC | Undisclosed | Undisclosed mechanism | Undisclosed | NCT02886494 | Recruiting | Charsire Biotechnology | December-16 | November-19 |

| NCT02467413 | Not yet recruiting | Charsire Biotechnology, A2 Healthcare Taiwan Corporation | December-17 | December-17 | ||||

| BAN2401 | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT01767311 | Active, not recruiting | Eisai | December-12 | November-18 |

| Benfotiamine | Metabolic | Synthetic thiamine (B1) | Improve multiple cellular processes (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02292238 | Recruiting | Burke Medical Research Institute, Columbia University, NIA, ADDF | November-14 | November-19 |

| BI 425809 | Neurotransmitter based | Glycine transporter 1 inhibitor | Facilitate NMDA receptor activity (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02788513 | Recruiting | Boehringer Ingelheim | August-16 | September-20 |

| BIIB092 | Anti-tau | Monoclonal antibody | Remove tau (DMT) | NCT03352557 | Not yet recruiting | Biogen | February-18 | September-20 |

| Bryostatin 1 | Metabolic, anti-amyloid | Protein kinase C modulator | Improve cellular processes (cognitive enhancer) and reduce amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT02431468 | Active, not recruiting | Neurotrope Bioscience | November-15 | May-17 |

| Candesartan | Neuroprotective, metabolic, anti-amyloid | Angiotensin receptor blocker | Improve vascular functioning and effects on amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT02646982 | Recruiting | Emory University | June-16 | September-21 |

| CB-AC-02 (Placenta derived-MSCs) | Regenerative | Stem cell therapy | Regenerate neurons | NCT02899091∗ | Not yet recruiting | CHA Biotech Co. | September-16 | June-18 |

| Cilostazol | Neuroprotective, metabolic | Phosphodiesterase 3 antagonist | Regulate cAMP and improve synaptic function (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02491268 | Recruiting | National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center, Japan | July-15 | December-20 |

| CPC-201 (donepezil/solifenacin combination) | Neurotransmitter based | Cholinesterase inhibitor + peripheral cholinergic antagonist | Improve acetylcholine signaling (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02549196 | Active, not recruiting | Allergan | October-15 | September-17 |

| Crenezumab | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT01998841 | Active, not recruiting | Genentech, NIA Banner Alzheimer's Institute | December-13 | February-22 |

| CT1812 | Metabolic | Sigma-2 receptor modulator | Improve synaptic dysfunction (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02907567∗ | Recruiting | Cognition Therapeutics | September-16 | May-17 |

| DAOIB | Neurotransmitter based | NMDA receptor modulation | Enhance NMDA activity (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02239003 | Recruiting | Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan | January-12 | December-17 |

| Deferiprone | Neuroprotective, anti-amyloid | Iron chelating agent | Reduce reactive oxygen species that damage neurons; effect on amyloid and BACE pathology (DMT) | NCT03234686 | Recruiting | Neuroscience Trials Australia | January-18 | December-21 |

| DHP1401 | Neuroprotective, metabolic | Affects cAMP activity | Improve synaptic function (cognitive enhancer) | NCT03055741 | Recruiting | Daehwa Pharmaceutical Co. | December-16 | September-18 |

| Dronabinol | Neurotransmitter based | CB1 and CB2 endocannabinoid receptor partial agonist | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT02792257 | Recruiting | Mclean Hospital, Johns Hopkins University | March-17 | December-20 |

| E2609 | Anti-amyloid | BACE inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT02322021 | Active, not recruiting | Eisai, Biogen | November-14 | April-18 |

| Formoterol | Metabolic | β2 adrenergic receptor agonist | Effects on multiple cellular pathways (DMT) | NCT02500784 | Recruiting | Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research, Mylan, Alzheimer's Association | January-15 | July-18 |

| GV1001 | Metabolic, anti-amyloid | Telomerase reverse transcriptase peptide vaccine | Effects on multiple cellular pathways including amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT03184467 | Recruiting | GemVax & Kael | June-17 | June-19 |

| hUCB-MSCs | Regenerative | Stem cell therapy | Regenerate neurons | NCT02054208∗ | Recruiting | Medipost Co. | February-14 | July-19 |

| NCT01547689∗ | Active, not recruiting | Affiliated Hospital to Academy of Military Medical Sciences, China | March-12 | December-16 | ||||

| NCT02513706 | Not yet recruiting | South China Research Center | May-16 | October-19 | ||||

| NCT02672306∗ | Not yet recruiting | South China Research Center | May-16 | October-19 | ||||

| NCT02833792 | Recruiting | Stemedica Cell Technologies | June-16 | June-18 | ||||

| NCT03172117 | Recruiting | Medipost Co. | May-17 | December-21 | ||||

| ID1201 | Anti-amyloid, metabolic, neuroprotective | Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway activation | Effects on multiple cellular pathways including amyloid metabolism (DMT) | NCT03363269 | Recruiting | IlDong Pharmaceutical Co | April-16 | December-18 |

| Insulin detemir (intranasal) | Metabolic | Increases insulin signaling in the brain | Enhance cell signaling and growth (DMT) | NCT01595646 | Active, not recruiting | Wake Forest School of Medicine, Alzheimer's Association | November-11 | March-17 |

| Insulin glulisine (intranasal) | Metabolic | Increases insulin signaling in the brain | Enhance cell signaling and growth (DMT) | NCT02503501 | Recruiting | Health Partners Institute | August-15 | September-18 |

| IONIS MAPTRx | Anti-tau | Microtubule-associated tau (MAPT) RNA inhibitor; antisense oligonucleotides | Reduce tau production (DMT) | NCT03186989 | Recruiting | Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Biogen | June-17 | February-20 |

| JNJ-54861911 | Anti-amyloid | BACE inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT02406027 | Active, not recruiting, Extension | Janssen | July-15 | October-22 |

| Levetiracetam | Metabolic | Anticonvulsant | Reduce neuronal hyperactivity (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02002819 | Recruiting | University of California, San Francisco | June-14 | December-17 |

| Liraglutide | Metabolic, neuroprotective | Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist | Enhance cell signaling (cognitive enhancer) | NCT01843075 | Recruiting | Imperial College London | January-14 | March-19 |

| Lithium | Neurotransmitter based | Ion channel modulator | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation, mania, psychosis) | NCT02129348 | Recruiting | New York State Psychiatric Institute, NIA | June-14 | April-19 |

| LM11A-31-BHS | Neuroprotective | Targets the p75 neurotrophin receptor | Improve synaptic functioning (cognitive enhancer) | NCT03069014 | Recruiting | PharmatrophiX Inc., NIA | February-17 | October-19 |

| L-Serine | Neuroprotective | Amino acid | Stabilize protein misfolding (DMT) | NCT03062449 | Recruiting | Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Brain Chemistry Laboratories | March-17 | August-18 |

| LY3002813 | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT03367403 | Recruiting | Eli Lilly | December-17 | December-20 |

| LY3202626 | Anti-amyloid | BACE Inhibitor | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | |||||

| NCT02791191 | Recruiting | Eli Lilly | June-16 | June-19 | ||||

| Methylene Blue | Anti-tau | Tau protein aggregation inhibitor | Reduce neurofibrillary tangle formation (DMT) | NCT02380573 | Active, not recruiting | Texas Alzheimer's Research and Care Consortium | July-15 | July-18 |

| MLC901 | Neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory | Natural product consisting of several herbs | Multiple cellular pathways (cognitive enhancer) | NCT03038035 | Recruiting | National University Hospital, Singapore | December-16 | June-19 |

| Montelukast buccal film | Anti-inflammatory | Leukotriene receptor antagonist | Reduce inflammation (cognitive enhancer) | NCT03402503 | Not yet recruiting | IntelGenx Corp. | February-18 | October-19 |

| MP-101 | Neuroprotective | Enhances mitochondrial functioning | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (psychosis) | NCT03044249 | Recruiting | Mediti Pharma | May-17 | November-18 |

| VX-745 (neflamapimod) | Metabolic | Selective p38 MAPK alpha inhibitor | Affect multiple cellular processes including inflammation and cellular plasticity (DMT) | NCT03402659 | Recruiting | EIP Pharma, VU University | December-17 | July-19 |

| Nicotinamide (Vitamin B3) | Anti-tau, neuroprotective | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Tau-induced microtubule depolymerization (DMT) | NCT03061474 | Recruiting | University of California, Irvine | July-17 | February-19 |

| Nicotine transdermal | Neurotransmitter based | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist | Enhance acetylcholine signaling (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02720445 | Recruiting | University of Southern California, NIA, ATRI, Vanderbilt University | January-17 | December-19 |

| Nilotinib | Anti-tau, anti-amyloid | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Reduce amyloid and tau production (DMT) | NCT02947893 | Recruiting | Georgetown University | January-17 | March-19 |

| Octagam 10% | Anti-amyloid | 10% human normal immunoglobulin | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT03319810 | Not yet recruiting | Sutter Health | October-17 | October-18 |

| ORM-12741 | Neurotransmitter based | Alpha-2c adrenergic receptor antagonist | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT02471196 | Active, not recruiting | Orion Corporation, Janssen | August-15 | December-17 |

| Pimavanserin | Neurotransmitter based | 5-HT2A inverse agonist | Improve neuropsychiatric symptoms (agitation) | NCT03118947 | Recruiting | Acadia | February-17 | June-20 |

| NCT02992132 | Active, not recruiting | Acadia | November-16 | February-18 | ||||

| Piromelatine | Neurotransmitter based | Melatonin receptor agonist; 5-HT 1A and 1D serotonin receptor agonist | Enhance cellular signaling (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02615002 | Recruiting | Neurim Pharmaceuticals | November-15 | March-18 |

| Posiphen | Anti-amyloid | Selective inhibitor of APP production | Reduce amyloid production (DMT) | NCT02925650∗ | Recruiting | QR Pharma, ADCS | March-17 | December-18 |

| Probucol | Neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory | Non-statin cholesterol reducing agent | Induce APOE activity and improve synaptic functioning (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02707458∗ | Not yet recruiting | Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Weston Brain Institute, McGill University | April-16 | May-18 |

| Rasagiline | Neuroprotective, metabolic, anti-amyloid | Monoamine oxidase B inhibitor | Enhance mitochondria activity and inactivate reactive oxygen species (cognitive enhancer), also effect on amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT02359552 | Recruiting | The Cleveland Clinic, Teva | May-15 | February-19 |

| Riluzole | Neuroprotective | Glutamate receptor antagonist; glutamate release inhibitor | Inhibit glutamate neurotransmission (cognitive enhancer) | NCT01703117 | Recruiting | Rockefeller University | November-13 | November-19 |

| RO7105705 | Anti-tau | Monoclonal antibody | Remove tau (DMT) | NCT03289143 | Recruiting | Genentech | October-17 | September-22 |

| Rotigotine | Neurotransmitter based | Dopamine agonist | Enhance dopamine neurotransmission (cognitive enhancer) | NCT03250741 | Recruiting | I.R.C.C.S. Fondazione Santa Lucia | June-16 | June-18 |

| S47445 | Neurotransmitter based | AMPA receptor agonist | Enhance NMDA receptor activity (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02626572 | Active, not recruiting | Servier | February-15 | December-17 |

| Sargramostim (GM-CSF) | Anti-amyloid, neuroprotective | Synthetic granulocyte colony stimulator | Stimulate innate immune system to remove amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT01409915 | Active, not recruiting | University of Colorado, Denver, The Dana Foundation | March-11 | December-17 |

| S-equol | Neuroprotective, anti-amyloid | Estrogen receptor B agonist | Improve synaptic functioning by competing with amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT03101085 | Recruiting | Ausio Pharmaceuticals, University of Kansas | May-17 | October-19 |

| Simvastatin + L-Arginine + Tetrahydrobiopterin (SLAT) | Neuroprotective, anti-amyloid | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor and antioxidant | Reduce cholesterol synthesis thereby reducing amyloid production (DMT) | NCT01439555 | Active, not recruiting | University of Massachusetts, Worcester | November-11 | December-17 |

| STA-1 | Neuroprotective | Antioxidant properties of echinacoside | Reduce oxidative stress (cognitive enhancer) | NCT01255046 | Not yet recruiting | Sinphar Pharmaceuticals | December-15 | December-18 |

| SUVN-502 | Neurotransmitter based | 5-HT6 antagonist | Improve neuronal signaling (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02580305 | Recruiting | Suven Life Sciences | September-15 | September-18 |

| Telmisartan | Neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory | Angiotensin II receptor blocker, PPAR-gamma agonist | Improve vascular functioning (DMT) | NCT02085265 | Recruiting | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, ADDF | March-14 | March-21 |

| UB-311 | Anti-amyloid | Active immunotherapy | Reduce amyloid (DMT) | NCT02551809 | Active, not recruiting | United Neuroscience | October-15 | December-18 |

| Valacyclovir | Neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory | Antiviral agent | Protect against HSV-1/2 infection and inflammation (DMT) | NCT02997982 | Recruiting | Umea University | December-16 | December-17 |

| NCT03282916 | Not yet recruiting | New York State Psychiatric Institute, NIH, NIA | December-17 | August-22 | ||||

| Xanamema | Neuroprotective | Blocks 11-HSD1 enzyme activity | Decrease cortisol production and neurodegeneration (DMT) | NCT02727699 | Recruiting | Actinogen Medical, ICON Clinical Research | March-17 | March-19 |

Abbreviations: ADCS, Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study; ADDF, Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; APOE, apolipoprotein E; APP, amyloid precursor protein; ATRI, Alzheimer's Therapeutic Research Institute; BACE, Beta-site Amyloid precursor protein Cleaving Enzyme; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CB, cannabinoid; DMT, disease-modifying therapy; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; GSK, GlaxoSmithKline; HMG-CoA, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme; HSD, hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; HT, hydroxytriptamine; hUCB-MSCs, human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NIA, National Institute on Aging; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; SNRI, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.

NOTE. Sixty-three agents in 75 phase II clinical trials currently ongoing as of January 30, 2018 according to clinicaltrials.gov.

NOTE. Bolded terms represent new entries into the 2018 phase II pipeline.

Phase I/II trials.

Of the 63 agents, there were 36 DMTs, 21 cognitive-enhancing agents, five drugs for behavioral symptoms, and one agent with an unknown MOA (Fig. 1; Table 3). Among the DMTs, 18 involved amyloid targets, nine addressed tau-related targets, one had a mechanism relevant to both amyloid- and tau-related targets, and eight had other MOAs (e.g., neuroprotection, metabolic, or anti-inflammatory). The DMTs include 11 immunotherapies (six addressing amyloid and five addressing tau). Of the DMTs, 12 are repurposed agents approved for use in another indication. There are eight trials involving stem cell therapies.

Of the drugs with amyloid targets, there were three Beta-site Amyloid percursor protein Cleavage Enzyme inhibitors, six immunotherapies, and two antiaggregation agents. Four agents involved antiaggregation and neuroprotection, and three agents were antiaggregation, neuroprotective, and metabolic agents. Fig. 3 shows the MOAs of agents in phase II.

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of action of agents in phase II.

Phase II trials are shorter in duration and smaller in terms of participant number than phase III trials: Phase II trials had a mean duration of 1221 days or 174 weeks (recruitment plus exposure period) and included an average of 156 participants in each trial. The average treatment period is 39 weeks.

3.4. Phase I

Phase I first-in-human trials are generally conducted in healthy volunteers and sometimes include a cohort of healthy elderly to begin to assess whether age affects the metabolism or excretion of the test agent. In some cases, phase I/IIa trials assess preliminary efficacy in patients with AD. Immunotherapies have the potential for long-term modification of the immune system, making participation of normal controls impermissible; these agents are typically assessed in patients with AD in phase I. Phase I includes single ascending dose trials assessing gradually increasing single doses and multiple ascending dose trials where individuals receive doses for 14–28 days [14], [15], [16]. Single ascending dose and multiple ascending dose studies usually include cohorts of 6–12 individuals assigned to drug or placebo (commonly four on placebo and eight on drug in a 12 person cohort). Food effects on drug absorption and drug-drug interactions are also assessed in phase I studies.

There are 23 agents in 25 trials in phase I. Of these, there were 17 DMTs, four cognitive-enhancing agents, and two agents of unknown MOA. No agents addressing neuropsychiatric symptoms were included. Of the 17 DMTs in phase I in 2018 (Fig. 1; Table 4), five were immunotherapies directed at amyloid-related targets, four had tau-related MOAs, one addressed both amyloid and tau targets, and seven had other mechanisms (e.g., neuroprotection, metabolic, regenerative, or anti-inflammatory). The MOA was not identified for two agents.

Table 4.

Agents currently in phase I of Alzheimer's disease drug development (as of 1/30/2018)

| Agent | Agent mechanism class | Mechanism of action | Therapeutic purpose | Clinicaltrials.gov ID | Status | Sponsor | Start date | Estimated end date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aducanumab | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT01677572 | Active, not recruiting | Biogen | October-12 | October-19 |

| AGN-242071 | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | Undisclosed | NCT03316898 | Not yet recruiting | Allergan | November-17 | June-18 |

| Allopregnanolone injection | Metabolic, neuroprotective | GABA receptor modulator | Improve neurogenesis (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02221622 | Recruiting | University of Southern California, NIA | August-14 | December-17 |

| BIIB076 | Anti-tau | Monoclonal antibody | Remove tau (DMT) | NCT03056729 | Recruiting | Biogen | February-17 | April-19 |

| Bisnorcymserine (BNC) | Neurotransmitter based | Butyrylcholinesterase inhibitor | Acetylcholine neurotransmission (cognitive enhancer) | NCT01747213 | Recruiting | NIA | January-13 | July-18 |

| Crenezumab | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT02353598 | Active, not recruiting | Genentech | February-15 | September-23 |

| hMSCs | Regenerative | Stem cell therapy | Regenerate neurons | NCT02600130 | Recruiting | Longeveron LLC | August-16 | October-19 |

| Idalopirdine (Lu AE58054) | Neurotransmitter based | 5-HT6 receptor antagonist | Improve neuronal signaling (cognitive enhancer) | NCT03307993 | Recruiting | H. Lundbeck A/S | September-17 | January-18 |

| Insulin aspart (Intranasal) | Metabolic | Increases insulin signaling in the brain | Enhance cell signaling and growth (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02462161 | Recruiting | Wake Forest School of Medicine, NIA, General Electric | May-15 | July-18 |

| JNJ-63733657 | Anti-tau | Monoclonal antibody | Remove tau (DMT) | NCT03375697 | Recruiting | Janssen | January-18 | February-19 |

| KHK6640 | Anti-amyloid | Anti-Aβ peptide antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT03093519 | Active, not recruiting | Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. | March-17 | June-18 |

| Lu AF20513 | Anti-amyloid | Polyclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT02388152 | Active, not recruiting | H. Lundbeck A/S | March-15 | October-18 |

| LY3002813 | Anti-amyloid | Monoclonal antibody | Remove amyloid (DMT) | NCT02624778 | Recruiting | Eli Lilly and Company | December-15 | June-20 |

| LY3303560 | Anti-tau | Monoclonal antibody | Remove tau (DMT) | NCT02754830 | Recruiting | Eli Lilly and Company | April-16 | April-18 |

| NCT03019536 | Recruiting | Eli Lilly and Company | January-17 | February-20 | ||||

| NDX-1017 | Regenerative | Hepatocyte growth factor | Regenerate neurons | NCT03298672 | Recruiting | M3 Biotechnology, ADDF, Biotrial Inc. | October-17 | June-18 |

| NP001 | Anti-inflammatory | Immune regulator of inflammatory monocytes/macrophages | Activate immune system (DMT) | NCT03179501 | Recruiting | Neuraltus Pharmaceuticals, University of Hawaii | September-17 | December-17 |

| NPT088 | Anti-amyloid, Anti-tau | IgG1 Fc-GAIM fusion protein | Clear amyloid and tau (DMT) | NCT03008161 | Recruiting | Proclara Biosciences | December-16 | December-18 |

| Oxaloacetate (OAA) | Metabolic | Mitochondrial enhancer | Enhance multiple cellular processes (DMT) | NCT02593318 | Recruiting | University of Kansas Medical Center | October-15 | October-18 |

| RGN1016 | Undisclosed | Undisclosed mechanism | Undisclosed | NCT02820155 | Recruiting | National Taiwan University | June-16 | February-17 |

| Salsalate | Anti-inflammatory | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory | Reduce neuronal injury (DMT) | NCT03277573 | Recruiting | University of California, San Francisco | July-17 | October-18 |

| TAK-071 | Neurotransmitter based | Muscarinic M1 receptor modulator | Enhance acetylcholine neurotransmission (cognitive enhancer) | NCT02769065 | Recruiting | Takeda | May-16 | March-18 |

| Telmisartan | Neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory | Angiotensin II receptor blocker, PPAR-gamma agonist | Improve vascular functioning and effects on amyloid pathology (DMT) | NCT02471833 | Recruiting | Emory University | April-15 | March-18 |

| TPI-287 | Anti-tau | Microtubule protein modulator | Reduce tau-mediated cellular damage (DMT) | NCT01966666 | Active, not recruiting | University of California, San Francisco | November-13 | November-17 |

| Vorinostat | Neuroprotective | Histone deacetylase inhibitor | Enhance multiple cellular processes including tau aggregation and amyloid deposition (DMT) | NCT03056495 | Recruiting | German Center for Neurodegenerative Diseases, University Hospital, Bonn, University of Gottingen | September-17 | October-19 |

Abbreviations: ADDF, Alzheimer's Drug Discovery Foundation; BACE, Beta-site Amyloid precursor protein Cleaving Enzyme; DMT, disease-modifying therapy; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric acid; hMSCs, human mesenchymal stem cells; NIA, National Institute on Aging; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

NOTE. Twenty-three agents in 25 phase I clinical trials currently ongoing as of January 30, 2018 according to clinicaltrials.gov.

NOTE. Bolded terms represent new entries into the 2018 phase I pipeline.

Phase I trials had an average duration of 982 days or 140 weeks (recruitment and treatment period) and included a mean number of 73 participants in each trial.

3.5. Trial sponsors

Across all trials, 56.6% are sponsored by the biopharma industry, 31.6% by Academic Medical Centers (with funding from National Institutes of Health, industry, or other entities), and 8.8% by others. Table 5 shows the sponsor of agents is different by trial phases.

Table 5.

Trial sponsor for each phase of development

| Sponsor | N of trials (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | Phase II | Phase III | |

| Biopharma | 13 (52.0) | 37 (49.3) | 26 (74.3) |

| Academic Medical Centers | 6 (24.0) | 19 (25.3) | 3 (8.6) |

| National Institutes of Health (NIH) | 1 (4.0) | 0 | 0 |

| NIH and industry | 0 | 2 (2.7) | 0 |

| Consortium/foundation | 0 | 3 (4.0) | 0 |

| NIH and Academic Medical Centers | 2 (8.0) | 3 (4.0) | 2 (5.7) |

| Industry and consortium/foundation | 2 (8.0) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (2.9) |

| Other combinations | 1 (4.0) | 9 (12.0) | 3 (8.6) |

3.6. Biomarkers

Table 6 shows the biomarkers used as outcome measures in current phase II and phase III AD clinical trials as described in the federal website; not all trial descriptions in clinicaltrials.gov note if biomarkers are included in the trial.

Table 6.

Biomarkers as outcome measures in phase II and phase III trials for agents in the Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline (clinicaltrials.gov; January 30, 2018)

| Biomarker | N of trials (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Phase III | Phase II | |

| CSF amyloid | 13 (37.1) | 17 (22.7) |

| CSF tau | 14 (40.0) | 17 (22.7) |

| FDG-PET | 5 (14.3) | 10 (13.3) |

| vMRI | 9 (25.7) | 7 (9.3) |

| Plasma amyloid | 2 (5.7) | 5 (6.7) |

| Plasma tau | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

| Amyloid PET | 11 (31.4) | 8 (10.7) |

| Tau PET | 0 | 1 (1.3) |

Abbreviations: CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose; PET, positron emission tomography; vMRI, volumetric magnetic resonance imaging.

AD biomarkers served as secondary outcomes in 18 phase III DMT trials and 20 phase II DMT trials. The most common biomarkers used were CSF amyloid, CSF tau, volumetric magnetic resonance imaging, and amyloid PET. One study reported using tau PET as a secondary outcome.

Amyloid biomarkers can be used to establish the presence of amyloid abnormalities and support the diagnosis of AD. Of the 25 phase III DMT trials, five trials used amyloid-PET as an entry criterion, two used CSF-amyloid, and seven used either amyloid-PET or CSF-amyloid. Ten out of 38 phase II DMT trials used amyloid-PET as an entry criterion, five used CSF-amyloid, and two used either amyloid-PET or CSF-amyloid. Eleven DMT trials in phase III and 21 in phase II did not require biomarker confirmation of AD for trial entry.

3.7. Comparison to 2017 pipeline

Compared with the 2017 pipeline, there are four new agents in phase III (AXS-05, octohydroaminoacridine succinate, escitalopram, and zolpidem), 14 in phase II (BIIB092, deferiprone, DHP1401, GV1001, ID1201, IONIS MAPTRx, LM11A-31-BHS, LY3002813, MLC901, MP-101, montelukast, VX-745, RO7105705, and rotigotine), and eight in phase I (NDX-1017, salsalate, vorinostat, BIIB076, JNJ-63733657, NP001, NPT088, and AGN-242071). Only one of the four new agents in phase III, (octohydroaminoacridine succinate) was previously present in phase II. Of the new agents in phase II, three of the 14 were previously noted in phase I (LY3002813, RO7105705, and VX-745). There are seven repurposed agents in phase III and 24 in phase II of the AD pipeline.

Eight agents listed in phase III in 2017 [7] failed in clinical trials as of January 30, 2018. These included the 5-HT6 inhibitors idalopirdine and intepirdine [17]. Three trials studying solanezumab (EXPEDITION studies) in prodromal/mild AD have been terminated as the study's primary end point was not met. The TOMMORROW studies (TOMM40301 and 303) studying pioglitazone were terminated in early 2018. Other trials failing to meet their primary outcomes included AC-1204, aripiprazole, MK-8931, nilvadipine and azeliragon. Two phase III trials for brexpiprazole as treatment for agitation in AD have completed and a third phase III trial is planned to begin in 2018.

Six agents were listed in phase II in 2017 and are not listed in any phase in 2018 and are no longer in development at this time (they could re-enter development). Trials of four agents were completed in 2017 and are not listed in the 2018 pipeline: BI409306, adenosine triphosphate, PQ912, and T-817MA. The trial status for NewGam 10% intravenous immunoglobulin changed to “unknown” because it has not been updated for more than 2 years on clinicaltrials.gov. Trials for the following five agents in phase I in 2017 were either completed or terminated and are not listed in the 2018 pipeline: BPN14770, PF-06751979, NGP 555, HTL0009936, and LY2599666.

4. Discussion

The Food and Drug Administration approved 46 new drugs (not including new doses, new formulations, or combinations of existing agents) in 2017. Six agents were approved for central nervous system disorders: edaravone for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cerliponase alfa for Batten disease, valbenazine for tardive dyskinesia, deutetrabenazine for chorea associated with Huntington's disease, ocrelizumab for relapsing-remitting and primary progressive multiple sclerosis, and safinamide for patients with Parkinson's disease experiencing “off” episodes (https://fda.gov/drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess). Three of these agents are DMTs (edaravone, cerliponase alfa, and ocrelizumab), and three are symptomatic therapies for amelioration of motor disorders. There were no new drug approvals for treatment of AD; none have been approved since 2003 [5].

Review of the 2018 AD drug development pipeline shows that most agents have MOAs directed at disease modification (63% across all phases); 23% are cognitive-enhancing agents, and 12% are drugs directed at controlling neuropsychiatric symptoms (three agents have undisclosed MOAs). A few new agents have entered the pipeline when compared with the 2017 review [7]: there are eight new agents in phase I, 14 in phase II, and four in phase III. Several agents have exited the pipeline including: five in phase I, five in phase II, and eight in phase III.

5-hyroxytryptamine-6 receptor antagonists have represented a substantial segment of the AD drug development pipeline with several agents exploring this cognitive enhancing mechanism. SAM-531 (also PF-052-12365) was assessed in a clinical trial of patients with mild-moderate AD not on therapy with memantine or a cholinesterase inhibitor. The trial was interrupted after an interim analysis suggested that all doses in the trial were futile. SB742457 (intepirdine) had evidence of efficacy in a phase II clinical trial [18] but failed to meet primary outcomes in a more recent phase III trial [19]. Similarly, LU-AE-58054 (idalopirdine) achieved a significant benefit on the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale [20] in phase II but failed to meet its primary outcomes in three phase III trials [17]. Other agents in this class are currently in trials (Suvn-502) or have shown efficacy in preclinical models (PRX-07034Z) [21]. Although recent trials have not demonstrated a drug-placebo difference with 5-HT6 antagonists, unresolved issues regarding the diagnosis of AD in trials not requiring biomarker confirmation, failure of decline of placebo groups in some trials, recruitment of atypical forms of AD (due to exclusion of standard of care with memantine and cholinesterase inhibitors), and dose preclude definitive conclusions about efficacy of this mechanism based on the existing trials.

Phosphodiesterases (PDEs) comprise a group of 11 families of enzymes that regulate cyclic adenosine monophosphate and cyclic guanosine monophosphate and are involved in neuroplasticity and memory consolidation [22], [23], [24], [25]. Several PDE inhibitors have been assessed in clinical trials of AD or MCI [26], and there are currently three PDE inhibitors in phase I and three in phase II. Three of the agents are PDE9 inhibitors, two are PDE 4 inhibitors, and 1 is a PDE 3 inhibitor. Trial outcomes will determine if PDE inhibitors produce cognitive benefit, if inhibition of one of the enzymes is more effective, and what population of patients is more benefited by treatment.

Biomarkers are important for the develeopment of both symptomatic and disease-modifying drugs. The use of biomarkers has become widespread in trials of DMTs, but biomarkers for symptomatic agents are more unusual. PDE9 inhibitors reduce CSF cyclic guanosine monophosphate, a second messenger that activates intracellular protein kinases. Measures of cyclic guanosine monophosphate have been used as a translational biomarker to establish target engagement and dose-response relationships in both humans and nonhuman primates [27], [28].

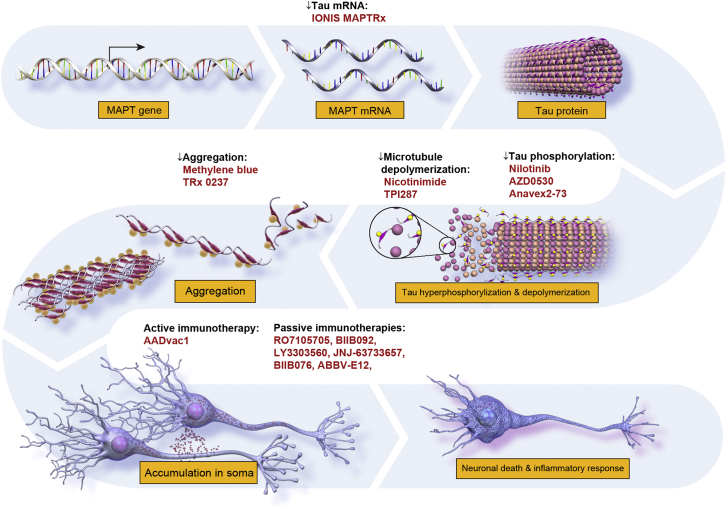

An increasing number of agents are directed at tau-related targets. Neurofibillary tangles, consisting of aggregates of phosphorylated microtubule-associated tau protein, are one of two major pathological hallmarks of AD [1], [2], [29]. Seminal clinicopathological correlation studies conducted by Braak and Braak [30], demonstrating that neurofibrillary tangle burden more closely correlate with cognitive decline than amyloid plaque load, indicate that agents directed against aberrant tau protein could serve as important anti-AD agents. Normal tau protein goes through multiple biological transformations in AD, and strategies to target tau are diverse. Fig. 4 depicts tau's role in AD pathogenesis and shows the purported MOA of candidate therapies directed at tau biology.

Fig. 4.

Site of action of anti-tau agents.

Tau remains an important but largely untested target for disease modification in AD. The first anti-tau programs were directed at reducing tau aggregation. The preliminary results of these studies were largely disappointing, and agents directed against tau aggregation are being re-evaluated [31]. More recently, immunotherapy strategies have achieved ascendency in the pipeline with seven tau immunotherapies entering phase I or II testing. Among the unknowns for tau immunotherapy programs are: (1) which is the most appropriate tau epitope to target, (2) what site of activity is required for effectiveness (intraneuronal vs. extracellular), and (3) what level of target engagement is required for efficacy [32]. The emergence of tau radioligands detectable by PET may provide key insights into these questions [33]; this technology remains expensive, has limited availability, and understanding of its interpretation is evolving.

A concerning observation derived from this AD pipeline review is the lack of agents targeting the moderate to advanced stages of AD. Only 26 trials permit inclusion of participants with scores of 14 or less, and only 12 include participants with scores of 10 or less. Together, these studies intend to enroll only 1720 participants. With over 15 million people affected by AD dementia worldwide [34], there is an urgent need to develop more effective symptomatic treatments for moderate to advanced stage disease. The paucity of agents directed at this population represents a significant weakness of the AD drug development pipeline.

A challenge for AD drug development is the lack of surrogate biomarkers. Surrogate markers—measures of disease that can be substituted for a clinical end point (i.e., hemoglobin A1c in diabetes)—predict clinical outcomes and accelerate drug development [35]. In the current AD landscape, there are few biomarkers and no accepted surrogate markers. The primary utility of existing AD biomarkers is to improve diagnostic accuracy [36], and these have been incorporated into current research criteria [37], [38], [39]. Previous research shows that misdiagnose rates in AD clinical trials can exceed 20% [40] and could contribute importantly to trial failure. Diagnostic verification is particularly important in trials of DMTs. Review of the 2018 pipeline reveals that a surprisingly low percentage of trials of DMTs require diagnostic biomarkers for entry or as secondary outcomes. The development and use of biomarkers for AD clinical trials remain a crucial unmet goal for the field.

Successful drug development requires effective recruitment of clinical trial participants and efficient execution of clinical trials in addition to drugs that are produced by rigorous disciplined drug development processes. Challenges of recruitment have become especially acute as prevention trials have become more numerous. Participants are cognitively normal, are not health-care seeking, and may not know their risk status. There are currently several efforts in the AD drug development arena that address these critical issues. Online registries are increasingly used to identify and educate possible trial participants. These registries vary in nature, with some collecting a minimum of information (age, interest in trials) and others collecting extensive cognitive, clinical, and demographic information [41], [42]. The over-arching purpose of these registries is to identify interested individuals that can be assessed for appropriateness for clinical trials and enlist them if they have the prespecified biomarker profile required for trial participation. Optimizing the use of registries to enhance trial recruitment will be among the important lessons from studying the current registries.

Clinical trial efficiency can be improved with more rapid clinical trial site start up (facility review, budget acceptance, and so on), pre-certified raters, use of a single institutional review board, and rapid recruitment of appropriate participants. Addressing each of these aspects of efficient trial site function can help accelerate clinical trial execution and drug development. In the United States, the Global Alzheimer Platform, the National Institutes of Health, the Alzheimer's Association TrialMatch program, the Alzheimer's Clinical Trial Consortium, and other initiatives are striving to improve trial efficiency [41], [43]. In Europe, the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia program is part of the Innovative Medicines Initiative and is addressing many of the same issues, especially as they apply to phase II clinical trials [44].

Clinicaltrials.gov has shortcomings that are important to recognize when considering the data presented here. The information provided may not represent the entire universe of AD drug development: not all phase I trials, especially those conducted outside the United States, may be registered in the database and our phase I data may underestimate the number of phase I candidates. Trials are required to be registered within 21 days of entering the first patient into the trial [9], but not all sponsors may meet this deadline. The Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act requires all trials to be registered, and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors requires trials to be registered to be eligible for publication [45]; recent reviews show a high rate of compliance with the registration rules [10], [11], [12]. The clinicaltrials.gov database is the most comprehensive of any existing trial database and provides credible data for drawing conclusions about AD drug development. We stopped entering new data into our database at a time that allowed submission, peer review, and publication; the data presented are a few months out-of-date (data collection stopped on January 30, 2018).

This review of the 2018 AD drug development pipeline demonstrates the continuing commitment of the scientific community, pharmaceutical industry, and regulatory agencies to develop new drugs of AD. Trends evidenced in the 2018 pipeline include more trials in preclinical and prodromal populations and greater use of biomarkers to support the diagnosis of AD. Every trial is a learning opportunity and informs the drug development process. Success depends on establishing targets critical to the disease process, developing efficacious agents, and conducting trials rigorously.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: New treatments for Alzheimer's disease (AD) are urgently needed. The drug development process progresses from phase I to phase II and phase III. Trials are listed on the federal government database clinicaltrials.gov.

-

2.

Interpretation: A study of the clinicaltrials.gov database reveals that there are 112 agents in the pipeline; of these, 26 are in phase III, 63 in phase II, and 23 in phase I. More tau-related targets are included for drugs in the current pipeline than previously. Clinical trial organizations are evolving to support clinical trial performance.

-

3.

Future directions: More agents are required in the pipeline to assure successful development of new treatments for AD. The number and success of pipeline agents depends on basic science research and efficient trials.

Acknowledgments

J.C. acknowledges the funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (Grant: P20GM109025) and support from Keep Memory Alive.

Disclosures: J.C. has provided consultation to Acadia, Accera, Actinogen, ADAMAS, Alkahest, Allergan, Alzheon, Avanir, Axovant, Axsome, BiOasis Technologies, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eisai, Genentech, Grifols, Kyowa, Lilly, Lundbeck, Merck, Nutricia, Otsuka, QR Pharma, Resverlogix, Roche, Servier, Suven, Takeda, Toyama, and United Neuroscience companies. G.L. and A.R. have no disclosures. K.Z. is an employee of the Global Alzheimer Platform.

References

- 1.Masters C.L., Bateman R., Blennow K., Rowe C.C., Sperling R.A., Cummings J.L. Alzheimer's disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2015;1:15056. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheltens P., Blennow K., Breteler M.M., de Strooper B., Frisoni G.B., Salloway S. Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 2016;388:505–517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brookmeyer R., Johnson E., Ziegler-Graham K., Arrighi H.M. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brookmeyer R., Abdalla N., Kawas C.H., Corrada M.M. Forecasting the prevalence of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;14:121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings J.L., Morstorf T., Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug-development pipeline: few candidates, frequent failures. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:37–43. doi: 10.1186/alzrt269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings J., Morstorf T., Lee G. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline. Alzheimer's Dement. 2016;2016:222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cummings J., Lee G., Mortsdorf T., Ritter A., Zhong K. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2017. Alzheimer's Dement (N Y) 2017;3:367–384. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson K.L., Lauer M.S., Collins F.S. Toward a new era of trust and transparency in clinical trials. JAMA. 2016;316:1353–1354. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarin D.A., Tse T., Williams R.J., Carr S. Trial reporting in clinicaltrials.gov - the final rule. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1998–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1611785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lassman S.M., Shopshear O.M., Jazic I., Ulrich J., Francer J. Clinical trial transparency: a reassessment of industry compliance with clinical trial registration and reporting requirements in the United States. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015110. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller J.E., Wilenzick M., Ritcey N., Ross J.S., Mello M.M. Measuring clinical trial transparency: an empirical analysis of newly approved drugs and large pharmaceutical companies. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017917. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips A.T., Desai N.R., Krumholz H.M., Zou C.X., Miller J.E., Ross J.S. Association of the FDA Amendment Act with trial registration, publication, and outcome reporting. Trials. 2017;18:333–342. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2068-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson M.L., Chiswell K., Peterson E.D., Tasneem A., Topping J., Califf R.M. Compliance with results reporting at ClinicalTrials.gov. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1031–1039. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1409364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curry S., DeCory H.H., Gabrielsson J., Phase I. The first opportunity for extrapolation from animal data to human exposure. In: Edwards L.D., Fox A.W., Stonier, editors. Principles and Practice of Pharmaceutical Medicine. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2011. pp. 84–106. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelley J. Wiley-Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2009. Principles of CNS Drug Development: From Test Tube to Patient. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norfleet E., Gad S.C. Phase I clinical trials. In: Gad C.S., editor. Clinical Trials Handbook. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; New York, New York: 2009. pp. 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atri A., Frolich L., Ballard C., Tariot P.N., Molinuevo J., Boneva N. Effect of idalopirdine as adjunct to cholinesterase inhibitors on change in cognition in patients with Alzheimer disease: 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2018;319:130–142. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maher-Edwards G., Dixon R., Hunter J., Gold M., Hopton G., Jacobs G. SB-742457 and donepezil in Alzheimer disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:536–544. doi: 10.1002/gps.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lombardo I. Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease; Boston, MA: 2017. Results from the phase 3 MINDSET STUDY: a global, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of intepirdine in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkinson D., Windfeld K., Colding-Jorgensen E. Safety and efficacy of idalopirdine, a 5-HT6 receptor antagonist, in patients with moderate Alzheimer's disease (LADDER): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:1092–1099. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70198-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohler E.G., Baker P.M., Gannon K.S., Jones S.S., Shacham S., Sweeney J.A. The effects of PRX-07034, a novel 5-HT6 antagonist, on cognitive flexibility and working memory in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;220:687–696. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2518-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia-Osta A., Cuadrado-Tejedor M., Garcia-Barroso C., Oyarzabal J., Franco R. Phosphodiesterases as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer's disease. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2012;3:832–844. doi: 10.1021/cn3000907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heckman P.R., Blokland A., Ramaekers J., Prickaerts J. PDE and cognitive processing: beyond the memory domain. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2015;119:108–122. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reneerkens O.A., Rutten K., Steinbusch H.W., Blokland A., Prickaerts J. Selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors: a promising target for cognition enhancement. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;202:419–443. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1273-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heckman P.R., Wouters C., Prickaerts J. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors as a target for cognition enhancement in aging and Alzheimer's disease: A translational overview. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;21:317–331. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140826114601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prickaerts J., Heckman P.R.A., Blokland A. Investigational phosphodiesterase inhibitors in phase I and phase II clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:1033–1048. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1364360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boland K., Moschetti V., Dansirikul C., Pichereau S., Gheyle L., Runge F. A phase I, randomized, proof-of-clinical-mechanism study assessing the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the oral PDE9A inhibitor BI 409306 in healthy male volunteers. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017;32:e2569–e2576. doi: 10.1002/hup.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleiman R.J., Chapin D.S., Christoffersen C., Freeman J., Fonseca K.R., Geoghegan K.F. Phosphodiesterase 9A regulates central cGMP and modulates responses to cholinergic and monoaminergic perturbation in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;341:396–409. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.191353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crowther R.A. Straight and paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease have a common structural unit. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:2288–2292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braak H., Braak E. Evolution of the neuropathology of Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1996;165:3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1996.tb05866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bakota L., Brandt R. Tau biology and tau-directed therapies for Alzheimer's disease. Drugs. 2016;76:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedersen J.T., Sigurdsson E.M. Tau immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:394–402. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maass A., Landau S., Baker S.L., Horng A., Lockhart S.N., La Joie R. Comparison of multiple tau-PET measures as biomarkers in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2017;157:448–463. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reitz C., Brayne C., Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2011;7:137–152. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan P., Brown D.G., Lennard S., Anderton M.J., Barrett J.C., Eriksson U. Impact of a five-dimensional framework on R&D productivity at AstraZeneca. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018 doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hampel H., Lista S., Teipel S.J., Garaci F., Nistico R., Blennow K. Perspective on future role of biological markers in clinical therapy trials of Alzheimer's disease: a long-range point of view beyond 2020. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;88:426–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKhann G.M., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., Hyman B.T., Jack C.R., Jr., Kawas C.H. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Albert M.S., DeKosky S.T., Dickson D., Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Fox N.C. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubois B., Feldman H.H., Jacova C., Hampel H., Molinuevo J.L., Blennow K. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer's disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:614–629. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70090-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doody R.S., Farlow M., Aisen P.S. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Data A, Publication C. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab and bapineuzumab for Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1402193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aisen P., Touchon J., Andrieu S., Boada M., Doody R., Nosheny R.L. Registries and Cohorts to Accelerate Early Phase Alzheimer's Trials. A Report from the E.U./U.S. Clinical Trials in Alzheimer's Disease Task Force. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3:68–74. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2016.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong K., Cummings J. Healthybrains.org: from registry to randomization. J Prev Alz Dis. 2016;3:123–126. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2016.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cummings J.L., Aisen P., Barton R., Bork J., Doody R., Dwyer J. Re-engineering Alzheimer clinical trials: Global Alzheimer Platform Network. J Prevent Alz Dis. 2016;3:114–120. doi: 10.14283/jpad.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ritchie C.W., Molinuevo J.L., Truyen L., Satlin A., Van der Geyten S., Lovestone S. Development of interventions for the secondary prevention of Alzheimer's dementia: the European Prevention of Alzheimer's Dementia (EPAD) project. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:179–186. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00454-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Angelis C., Drazen J.M., Frizelle F.A., Haug C., Hoey J., Horton R. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1250–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]