ABSTRACT

Clinical use of voriconazole, posaconazole, and itraconazole revealed the need for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of plasma concentrations of these antifungal agents. This need for TDM was not evident from clinical trials. In order to establish whether this requirement also applies to isavuconazole, we examined the plasma concentrations of 283 samples from patients receiving isavuconazole in clinical practice and compared the values with those from clinical trials. The concentration distributions from real-world use and clinical trials were nearly identical (>1 μg/ml in 90% of patients). These findings suggest that routine TDM may not be necessary for isavuconazole in most instances.

KEYWORDS: therapeutic drug monitoring, isavuconazole

TEXT

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is now frequently used to optimize the safety and efficacy of antifungal agents (1–15). The need and utility of TDM are based on several widely accepted factors, including the lack of reliable dose-concentration relationships, relatively large interpatient pharmacokinetic variability, demonstrated relationships between plasma drug concentrations and efficacy or toxicity, and availability of a validated drug assays. These criteria have been fulfilled for the three antifungal triazoles itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole and for flucytosine. The importance of this management strategy for these antifungal agents has led to exploration of the need for TDM for new agents early in their clinical development and use.

Isavuconazole, a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal agent, is the most recently approved antifungal agent for treatment of systemic fungal infections (16, 17). Several pharmacokinetic features of isavuconazole identified during clinical development suggested little need for routine TDM (18–20). Specifically, isavuconazole pharmacokinetics are dose proportional over a wide dose range (40 to 600 mg), interpatient pharmacokinetic variability among patients is modest compared with that of other antifungal triazoles (coefficient of variation [CV], ∼60%), and no clear efficacy or toxicity concentration thresholds have been identified.

Pharmacokinetic factors indicative of the need for TDM are often not identified until data collected during real-world clinical use are available. In particular, most clinical-use pharmacokinetic studies detect pharmacokinetic variability that is in excess of that observed in healthy volunteers or defined patient populations from clinical trials (2, 10). The goal of this report was to explore isavuconazole concentrations from patients treated during real-world clinical use and compare the data with those from samples collected during clinical trials of drug development.

Astellas aided the development of a validated plasma-concentration assay for isavuconazole by the clinical diagnostic laboratory Viracor (Lee's Summit, MO) (18, 21). The assay utilized reversed-phase ultraperformance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) to measure isavuconazole concentrations in serum or plasma. From August 2015 to August 2016, following regulatory approval of isavuconazole, 283 plasma samples were collected at the request of clinicians as part of routine care and shipped to Viracor for assay. Findings from these samples were compared with plasma concentrations from >2,459 samples from 551 patients in three phase 3 trials with isavuconazole.

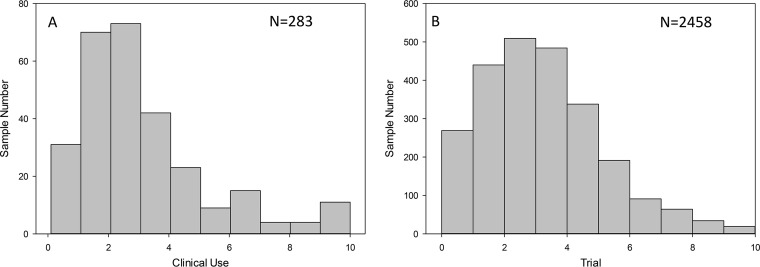

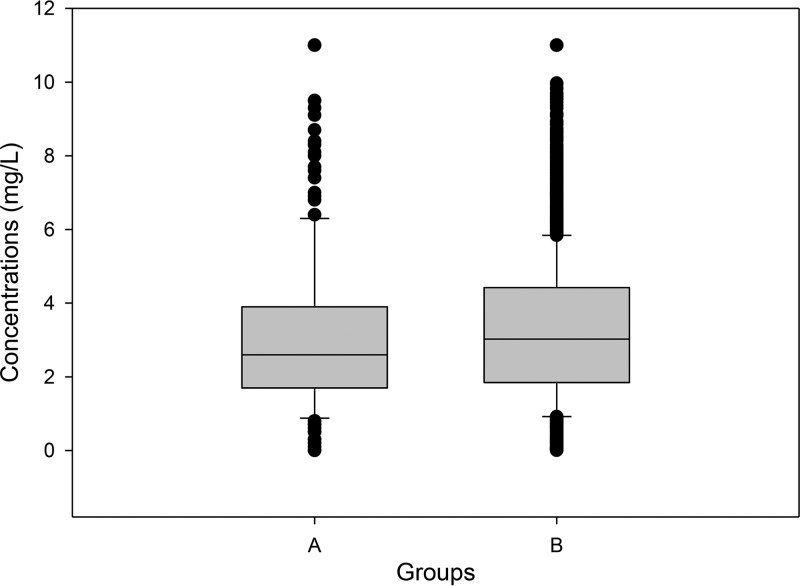

Figure 1 shows the distribution of serum and plasma concentrations in data sets from real-world clinical use and clinical trials. In general, the concentration distributions were similar for the two populations, as were the pharmacokinetic parameters and drug exposures (Fig. 2). For the current clinical-use population of 283 samples, the isavuconazole plasma concentration mean, median, and standard deviation values were 2.98, 2.6, and 1.91 μg/ml, respectively; the coefficient of variation was 64%. The clinical-trial concentration mean, median, and standard deviation values were 3.30, 3.02, and 2.18 μg/ml, respectively; the coefficient of variation was 66%. Mean concentrations in clinical use were statistically lower than those in trial patients (Mann-Whitney rank-sum test, P = 0.014).

FIG 1.

Histogram of clinical-use (A) and trial (B) isavuconazole concentrations.

FIG 2.

Box and whisker plot of clinical-use (A) and trial (B) isavuconazole concentrations.

Concentration thresholds associated with efficacy have been reasonably defined for itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole (∼1 μg/ml) (3). Similarly, concentrations of voriconazole and itraconazole commonly linked to toxicity have been defined (6, 7). Limited data are available to assess concentration thresholds for isavuconazole. Recent analysis of concentration data from the aspergillosis and other mold trials did not identify a threshold linked to outcome (21). Analysis of the trial and clinical-use data sets identified ∼10% of patients with concentrations below 1 μg/ml. This observation is quite different from those in clinical-use studies describing concentration monitoring with voriconazole and posaconazole, in which as many as 60% of patient values fell below this threshold (2, 10). Even with the newer posaconazole tablet formulation, the rate of suggested subtherapeutic concentrations can approach 30% (19, 20).

There are limitations to the current data set, primarily related to the lack of patient-level data. Because of this, we were unable to assess outcome relative to infection or the impact of isavuconazole concentrations on safety profiles. In addition, we do not have information regarding dosage or timing of concentration monitoring relative to drug administration. We speculate that approved dosing and trough concentrations were utilized in most patients, given the absence of recommendations for dose escalation in the literature and the convention of trough monitoring with other triazoles. Despite these limitations, these results can reassure clinicians that exposures in clinical use are very similar to those observed in clinical trials. Additionally, 90% of patients receiving isavuconazole would be anticipated to achieve a putative therapeutic concentration (>1 μg/ml). Whether additional studies will identify a different threshold of efficacy in mold infections or a toxicodynamic relationship remains to be seen as additional clinical-use cohorts are analyzed.

In the absence of additional data and lack of a defined threshold in clinical-trial analyses, the findings in this study support the premise that routine TDM is not required for patients receiving isavuconazole. However, there are circumstances where TDM may be warranted. These include patients who are receiving isavuconazole and who are displaying therapeutic failure or unexplained hepatotoxicity, as well as those who are noncompliant, obese, receiving concomitant medications that are predicted to reduce isavuconazole concentrations, age <18 years, or suffering from moderate hepatic failure (22).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Astellas Pharma, Inc. T.W. was supported in part for this work by the Henry Schueler Foundation.

D.A. has received grants from Astellas outside the submitted work. T.W. has received research grants to Weill Cornell Medicine and consulting fees from Astellas outside the submitted work. L.K., A.D., and T.K. are full-time employees of Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc. We have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wiederhold NP, Pennick GJ, Dorsey SA, Furmaga W, Lewis JS II, Patterson TF, Sutton DA, Fothergill AW. 2014. A reference laboratory experience of clinically achievable voriconazole, posaconazole, and itraconazole concentrations within the bloodstream and cerebral spinal fluid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:424–431. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01558-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson GR III, Rinaldi MG, Pennick G, Dorsey SA, Patterson TF, Lewis JS II. 2009. Posaconazole therapeutic drug monitoring: a reference laboratory experience. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:2223–2224. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00240-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andes D, Pascual A, Marchetti O. 2009. Antifungal therapeutic drug monitoring: established and emerging indications. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:24–34. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00705-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh TJ, Raad I, Patterson TF, Chandrasekar P, Donowitz GR, Graybill R, Greene RE, Hachem R, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Langston A, Louie A, Ribaud P, Segal BH, Stevens DA, van Burik JA, White CS, Corcoran G, Gogate J, Krishna G, Pedicone L, Hardalo C, Perfect JR. 2007. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis with posaconazole in patients who are refractory to or intolerant of conventional therapy: an externally controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 44:2–12. doi: 10.1086/508774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stott KE, Hope WW. 2017. Therapeutic drug monitoring for invasive mould infections and disease: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations. J Antimicrob Chemother 72:i12–i18. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pascual A, Calandra T, Bolay S, Buclin T, Bille J, Marchetti O. 2008. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with invasive mycoses improves efficacy and safety outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 46:201–211. doi: 10.1086/524669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lestner JM, Roberts SA, Moore CB, Howard SJ, Denning DW, Hope WW. 2009. Toxicodynamics of itraconazole: implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. Clin Infect Dis 49:928–930. doi: 10.1086/605499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith J, Safdar N, Knasinski V, Simmons W, Bhavnani SM, Ambrose PG, Andes D. 2006. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:1570–1572. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1570-1572.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Troke PF, Hockey HP, Hope WW. 2011. Observational study of the clinical efficacy of voriconazole and its relationship to plasma concentrations in patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:4782–4788. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01083-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trifilio S, Ortiz R, Pennick G, Verma A, Pi J, Stosor V, Zembower T, Mehta J. 2005. Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant 35:509–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dolton MJ, Ray JE, Chen SC, Ng K, Pont L, McLachlan AJ. 2012. Multicenter study of posaconazole therapeutic drug monitoring: exposure-response relationship and factors affecting concentration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:5503–5510. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00802-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jang SH, Colangelo PM, Gobburu JV. 2010. Exposure-response of posaconazole used for prophylaxis against invasive fungal infections: evaluating the need to adjust doses based on drug concentrations in plasma. Clin Pharmacol Ther 88:115–119. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park WB, Kim NH, Kim KH, Lee SH, Nam WS, Yoon SH, Song KH, Choe PG, Kim NJ, Jang IJ, Oh MD, Yu KS. 2012. The effect of therapeutic drug monitoring on safety and efficacy of voriconazole in invasive fungal infections: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 55:1080–1087. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imhof A, Schaer DJ, Schanz U, Schwarz U. 2006. Neurological adverse events to voriconazole: evidence for therapeutic drug monitoring. Swiss Med Wkly 136:739–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shields RK, Clancy CJ, Vadnerkar A, Kwak EJ, Silveira FP, Massih RC, Pilewski JM, Crespo M, Toyoda Y, Bhama JK, Bermudez C, Nguyen MH. 2011. Posaconazole serum concentrations among cardiothoracic transplant recipients: factors impacting trough levels and correlation with clinical response to therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 55:1308–1311. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01325-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marty FM, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Cornely OA, Mullane KM, Perfect JR, Thompson GR III, Alangaden GJ, Brown JM, Fredricks DN, Heinz WJ, Herbrecht R, Klimko N, Klyasova G, Maertens JA, Melinkeri SR, Oren I, Pappas PG, Racil Z, Rahav G, Santos R, Schwartz S, Vehreschild JJ, Young JA, Chetchotisakd P, Jaruratanasirikul S, Kanj SS, Engelhardt M, Kaufhold A, Ito M, Lee M, Sasse C, Maher RM, Zeiher B, Vehreschild MJ, VITAL and FungiScope Mucormycosis Investigators . 2016. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single-arm open-label trial and case-control analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 16:828–837. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maertens JA, Raad II, Marr KA, Patterson TF, Kontoyiannis DP, Cornely OA, Bow EJ, Rahav G, Neofytos D, Aoun M, Baddley JW, Giladi M, Heinz WJ, Herbrecht R, Hope W, Karthaus M, Lee DG, Lortholary O, Morrison VA, Oren I, Selleslag D, Shoham S, Thompson GR III, Lee M, Maher RM, Schmitt-Hoffmann AH, Zeiher B, Ullmann AJ. 2016. Isavuconazole versus voriconazole for primary treatment of invasive mould disease caused by Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi (SECURE): a phase 3, randomised-controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 387:760–769. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01159-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desai A, Kovanda L, Kowalski D, Lu Q, Townsend R, Bonate PL. 2016. Population pharmacokinetics of isavuconazole from phase 1 and phase 3 (SECURE) trials in adults and target attainment in patients with invasive infections due to Aspergillus and other filamentous fungi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:5483–5491. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02819-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin A, Pergam SA, Fredricks DN, Hoofnagle AN, Baker KK, Jain R. 2017. Evaluation of posaconazole serum concentrations from delayed-release tablets in patients at high risk for fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00569-. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00569-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tverdek FP, Heo ST, Aitken SL, Granwehr B, Kontoyiannis DP. 2017. Real-life assessment of the safety and effectiveness of the new tablet and intravenous formulations of posaconazole in the prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections via analysis of 343 courses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00188-. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00188-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai AV, Kovanda LL, Hope WW, Andes D, Mouton JW, Kowalski DL, Townsend RW, Mujais S, Bonate PL. 2017. Exposure-response relationships for isavuconazole in patients with invasive Aspergillosis and other filamentous fungi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01034-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01034-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitt-Hoffmann A, Roos B, Spickermann J, Heep M, Peterfai E, Edwards DJ, Stoeckel K. 2009. Effect of mild and moderate liver disease on the pharmacokinetics of isavuconazole after intravenous and oral administration of a single dose of the prodrug BAL8557. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 53:4885–4890. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00319-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]