ABSTRACT

SPR741 is a novel agent with structural similarity to polymyxins that is capable of potentiating the activities of various classes of antibiotics. Previously published studies indicated that although Enterobacteriaceae isolates had minimal susceptibilities to azithromycin (AZM), the in vitro antimicrobial activity of AZM against Enterobacteriaceae was enhanced when it was combined with SPR741. The current study evaluated the in vivo activity of human-simulated regimens (HSR) of AZM equivalent to clinical doses of 500 mg given intravenously (i.v.) every 24 h (q24h) and SPR741 equivalent to clinical doses of 400 mg q8h i.v. (1-h infusion), alone and in combination, against multidrug-resistant (MDR) Enterobacteriaceae. We studied 30 MDR Enterobacteriaceae isolates expressing a wide spectrum of β-lactamases (ESBL, NDM, VIM, and KPC), including a subset of isolates positive for genes conferring macrolide resistance (mphA, mphE, ermB, and msr). In vivo activity was assessed as the change in log10 CFU per thigh at 24 h compared with 0 h. Treatment with AZM alone was associated with net growth of 2.60 ± 0.83 log10 CFU/thigh. Among isolates with AZM MICs of ≤16 mg/liter, treatment with AZM-SPR741was associated with an average reduction in bacterial burden of −0.53 ± 0.82 log10 CFU/thigh, and stasis to 1-log kill was observed in 9/11 isolates (81.8%). Combination therapy with an AZM-SPR741 HSR showed promising in vivo activity against MDR Enterobacteriaceae isolates with AZM MICs of ≤16 mg/liter, including those producing a variety of β-lactamases. These data support a potential role for AZM-SPR741 in the treatment of infections due to MDR Enterobacteriaceae.

KEYWORDS: multidrug resistance, macrolide, pharmacodynamics, macrolides-lincosamides-streptogramin B, pharmacokinetics

INTRODUCTION

Treatment of infections with resistant Gram-negative bacteria poses an increasingly intractable challenge to clinicians both domestically and globally. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), infections due to multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, defined as those exhibiting acquired nonsusceptibility to at least one agent in each of three or more antimicrobial classes (1), are considered serious threats, while infections due to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are considered urgent threats requiring aggressive action (2). In 2013 alone, 9,300 CRE cases were documented in the United States, resulting in 610 cases of mortality (2). Resistance to treatment with β-lactam agents is frequently attributed to enzymatic inactivation of antimicrobial agents by β-lactamases such as Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC), extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL), and metallo-β-lactamases (MBL) (3). Many of the remaining agents available for treatment of MDR infections, such as colistin, are considered agents of last resort, as their use is frequently associated with dose-dependent toxicities (4). Furthermore, increasingly, even colistin resistance has become a clinical reality (5). Viewed together, these facts highlight a critical need for continued development of new pharmacological tools and a redoubled effort in the search for innovative mechanisms to combat this problem.

A particular hallmark of resistance by Gram-negative pathogens to many currently available agents is a lack of permeability of the bacterial outer membrane (OM). This effectively functions to limit access of antimicrobials to intracellular drug targets (6). SPR741 is a novel cationic peptide with structural similarities to polymyxin B (7). As with agents in the polymyxin class, SPR741 exerts its effect by means of binding interactions with the OM, resulting in disruption of membrane integrity (7). SPR741 acts as an antibiotic adjuvant, as it increases the permeability of bacterial cells to other antimicrobial agents and shows limited bacterial killing as monotherapy. Notably, the dose-limiting nephrotoxicity typically associated with the use of polymyxins has been mitigated for SPR741 via targeted structural modifications, resulting in an improved safety profile (7–9).

Initial in vitro studies demonstrated a potentiation of a multitude of conventional antimicrobial agents in the presence of SPR741 (7). Multifold reductions in fractional inhibitory concentrations (FIC) for several ATCC strains with a variety of agents combined with SPR741 lent early support for further development (7). Specifically, these findings showed significant potentiation of macrolides such as azithromycin (AZM) (7). Although macrolides are not typically used in the treatment of Enterobacteriaceae infections due to intrinsically high MICs, combination with SPR741 showed potential for rendering them efficacious. Of particular interest was the potential for in vivo activity of a macrolide-SPR741 combination against MDR Enterobacteriaceae, as this combination could theoretically circumvent inactivation by β-lactamases commonly expressed by these isolates. The current study sought to evaluate the in vivo potentiation capacity of SPR741 using human-simulated exposures to the compound in combination with AZM against MDR Enterobacteriaceae.

RESULTS

In vitro susceptibility.

For the isolates tested, the AZM, SPR741, and AZM-SPR741 MICs ranged from 8 to >128, 16 to >512, and 0.125 to >32 mg/liter, respectively. AZM, SPR741, and AZM-SPR741 MICs and known genotypic data for the 30 isolates that were utilized in the in vivo activity studies are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

MICs of AZM, SPR741, and the AZM-SPR741 combinationa against Enterobacteriaceae isolates utilized in the in vivo activity studies

| Isolate | MIC (mg/liter) |

β-Lactamase encoded and macrolide resistance gene(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AZM | SPR741 | AZM-SPR741 | ||

| EC 548 | 8 | 32 | 0.125 | KPC-3, OXA-9, TEM-1A |

| EC C24-11 | 8 | 32 | 0.125 | No data available |

| EC 541 | 16 | 64 | 0.125 | NDM-7, CMY-42 |

| EC 550 | 8 | 16 | 0.125 | NDM-1, TEM-1B, CMY-6 |

| KP C8-9 | 32 | 128 | 0.125 | TEM-1, SHV-12, KPC-2 |

| EC 547 | 16 | 32 | 0.125 | TEM-52B, mphA |

| EC 553 | 8 | 32 | 0.125 | TEM-1B |

| EC 549 | 32 | 32 | 0.125 | TEM-1B |

| KP 684 | 16 | 128 | 0.125 | IMP-4, TEM-1B, OKP-B-2, OXA-1, SFO-1 |

| EC 556 | 8 | 64 | 0.25 | CMY-2 |

| EC 554 | 16 | 32 | 0.25 | CMY-2 |

| EC 545 | 16 | 32 | 0.5 | NDM-1, TEM-1B, CMY-6, CTX-M-15, OXA-2 |

| EC C21-19 | >128 | 32 | 1 | No data available |

| KP C4-10 | 16 | 64 | 1 | TEM-1, SHV-11, CTX-M-15, KPC-3, OXA 9 |

| EC 540 | 128 | 32 | 1 | NDM-6, OXA-9, TEM-1A, CMY-42, CTX-M-15, OXA-1, mphA |

| EC C4-29 | 64 | 128 | 2 | No data available |

| KP 329B | 128 | 64 | 2 | KPC-2, SHV-11, SHV-5, OXA-9, TEM-1, mphA |

| EC 546 | >128 | 32 | 4 | NDM-1, CMY-6, OXA-1, mphA |

| EC C24-30 | 32 | 256 | 4 | No data available |

| EC 543 | >128 | 64 | 4 | NDM-5, TEM-1B, CMY-42, CTX-M-15, SHV-12, OXA-1, mphA |

| KP C4-14 | 64 | 64 | 4 | TEM-1, SHV-12, KPC-3 |

| KP C6-5 | 32 | >512 | 4 | AmpC, TEM-1, SHV-2, KPC-3, OXA-9, OXA-1 |

| KP 510 | 128 | 64 | 4 | CTX-M-11, SHV-11, DHA-1, TEM-1A, mphA, mphE, msrE |

| EC 555 | >128 | 16 | 4 | TEM-1B, CTX-M-14, mphA |

| KP 683 | >128 | 16 | 8 | TEM-1B, CTX-M-14, SHV-11, DHA-1, erm(42) |

| EC 544 | >128 | 32 | 16 | NDM-7, TEM-1B, CTX-M-15, ermB |

| KP C21-22 | >128 | >512 | 32 | TEM-1, KPC-2 |

| KP 666 | >128 | 128 | >32 | NDM-1, OXA-232, OXA-9, TEM-1A, CTX-M-15, OXA-1, mphE, msr |

| KP 676 | >128 | >512 | >32 | VIM-27, CTX-M-15, SHV-11, OXA-1, mphA |

| KP 671 | >128 | >512 | >32 | VIM-27, CTX-M-15, SHV-11, OXA-1, mphA |

A fixed SPR741 concentration of 8 mg/liter was used.

AZM protein binding studies in mouse plasma.

The percentages of protein binding by AZM in mouse plasma were comparable across the range of doses chosen. Table 2 shows individual values for free (unbound) and total AZM concentrations for the 3 doses examined. Therefore, an average free fraction of 0.98 was utilized in subsequent pharmacokinetic analyses to establish the human-simulated regimen (HSR) for AZM.

TABLE 2.

Total and free (unbound) AZM concentrations in plasma from pooled mice at 1 h following the administration of a range of AZM doses

| Dose (mg/kg) | Group | Concn in plasma (mg/liter) |

Free (unbound) fraction | Avg free fraction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free AZM | Total AZM | ||||

| 6.25 | 1 | 0.44 | 0.54 | 0.83 | 0.92 |

| 2 | 0.33 | 0.38 | 0.87 | ||

| 3 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 1.06 | ||

| 12.5 | 1 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| 2 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 1.03 | ||

| 3 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.98 | ||

| 25 | 1 | 1.74 | 1.90 | 0.92 | 1.02 |

| 2 | 1.65 | 1.66 | 0.99 | ||

| 3 | 1.65 | 1.44 | 1.15 | ||

| All doses | 0.98 | ||||

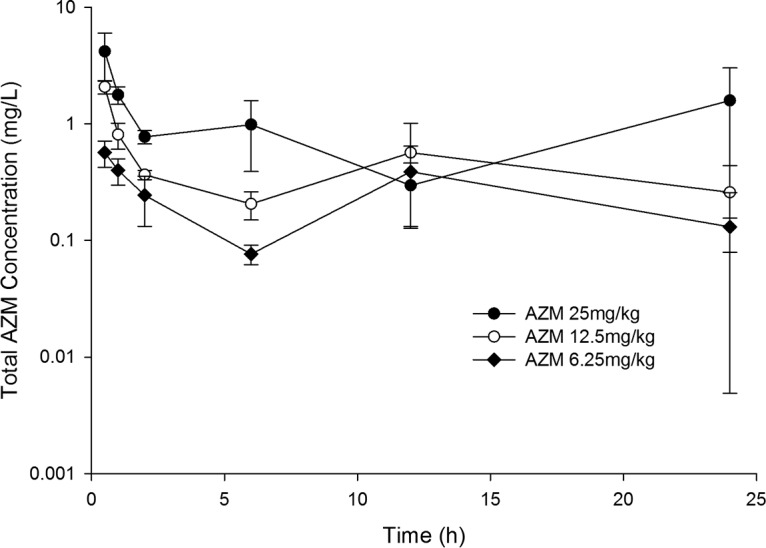

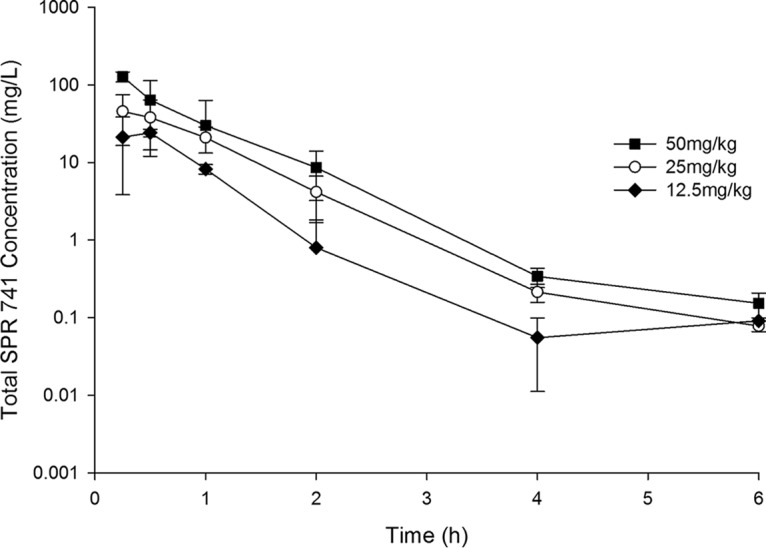

Single-dose AZM and SPR741 pharmacokinetic studies.

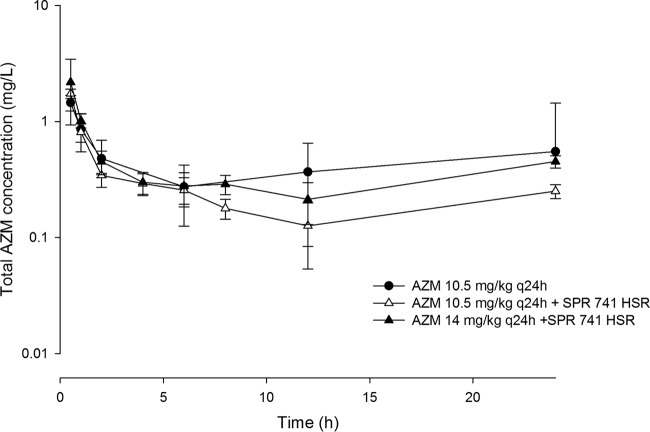

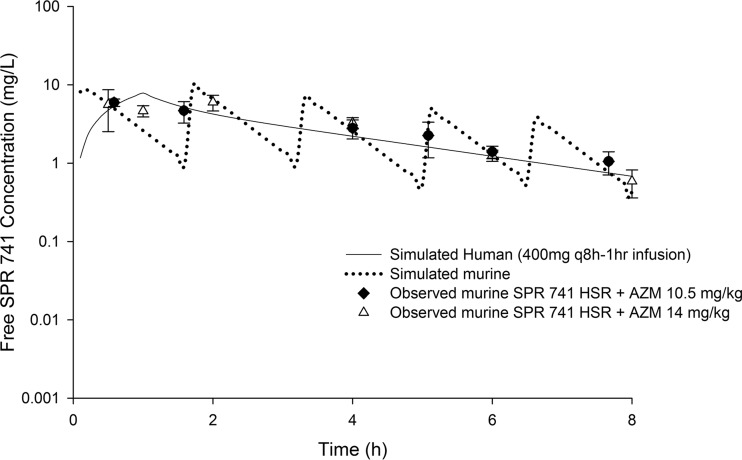

AZM was satisfactorily detected in mouse plasma for all doses examined following subcutaneous (s.c.) administration, as shown in Fig. 1. SPR741 was also satisfactorily detected in mouse plasma for all doses examined following subcutaneous administration, as shown in Fig. 2. Utilizing a one-compartment model, best-fit pharmacokinetic parameters for SPR741 in the neutropenic infection model were as follows: volume of distribution (V) = 0.35 liters/kg, absorption rate constant (k01) = 16.15 h−1, and elimination rate constant (k10) = 1.56 h−1. The estimate for the volume of distribution was conditioned on the unknown bioavailability from the s.c. injection.

FIG 1.

Total plasma AZM concentration-time profiles in a neutropenic thigh infection model following administration of single subcutaneous doses. Data are means ± standard deviations.

FIG 2.

Total plasma SPR741 concentration-time profiles in a neutropenic thigh infection model following administration of single subcutaneous doses. Data are means ± standard deviations.

Samples were assayed to determine SPR741 concentrations as described above. Low, medium, and high predicted quality control (QC) values were 150, 3,750, and 37,500 ng/ml, respectively. Observed values are reported for all runs (n = 8) as follows (mean, standard deviation [SD], coefficient of variation [%CV]): low (155.06 ng/ml, 8.87 ng/ml, 5.72%), medium (3,983.13 ng/ml, 103.13 ng/ml, 2.59%), and high (40,975 ng/ml, 821.79 ng/ml, 2.01%). QC values for SPR741 were linear across the range 50 to 50,000 ng/ml (r2 = 0.9991). Azithromycin was assayed using predicted QC values of 30, 750, and 7,500 ng/ml over all runs (n = 4). Observed values were reported as follows: low (31.78 ng/ml, 3.32 ng/ml, 10.45%), medium (751.88 ng/ml, 50.72 ng/ml, 6.75%), and high (7,590 ng/ml, 589.53 ng/ml, 7.77%). QC values for AZM were linear across the range of 10 to 10,000 ng/ml (r2 = 0.9919).

Pharmacokinetic studies of human-simulated AZM and SPR741 exposures.

Based on the area under the concentration-time curve for the free, unbound fraction of the drug from 0 to 24 h (fAUC0–24), an AZM exposure for mice comparable to that for humans following the intravenous (i.v.) administration of 500 mg every 24 h (q24h) was attained when mice were administered 10.5 mg/kg of body weight every 24 h s.c. A comparison of fAUC0–24 values achieved with AZM in humans with those in mice receiving the selected human-simulated regimen is presented in Table 3. Since the AZM exposure was reduced by 40% when AZM was coadministered with the SPR741 HSR, (Table 3 and Fig. 3) an increase in the AZM dose was warranted for those animals receiving treatment with the combination in order to attain the target human exposure. Increasing the AZM dose to 14 mg/kg q24h concomitantly with the SPR741 HSR achieved the targeted ƒAUC0–24 for the macrolide (Table 3). The mechanism of interaction between AZM and SPR741 was not examined, as it was beyond the scope of this investigation.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of ƒAUC0–24 values achieved with AZM in humans receiving 500 mg q24h i.v. and those in mice receiving a human-simulated regimen s.c.

| Species | AZM dose q24h | Regimen | fAUC0–24 (mg · h/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 500 mg | AZM | 8.93 |

| Mouse | 10.5 mg/kg | AZM alone | 10.56 |

| 10.5 mg/kg | AZM + SPR741 HSR | 6.14 | |

| 14 mg/kg | AZM + SPR741 HSR | 8.97 |

FIG 3.

Total plasma azithromycin concentration-time profiles in a neutropenic thigh infection model following administration of human-simulated doses alone or in combination with a human-simulated SPR741 regimen. Data are means ± standard deviations.

Free SPR741 drug exposures in mice were comparable to those predicted in humans following the administration of 400 mg q8h as a 1-h infusion when the mice were administered a 5-dose regimen (0 h, 36 mg/kg; 1.5 h, 33 mg/kg; 3.25 h, 23 mg/kg; 5 h, 16 mg/kg; 6.5 h, 12 mg/kg). This regimen was repeated every 8 h over a 24-h period (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of SPR741 %fT>CT and ƒAUC0–24 values in humans receiving 400 mg q8h and mice receiving the human-simulated regimen

| Regimen | %fT>CT at the following CTa (mg/liter): |

ƒAUC0–24 (mg · h/liter) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 | ||

| Humanb | 100 | 85.8 | 55.0 | 24.2 | 0.8 | 0 | 68.77 |

| Murine HSRc | 97.5 | 81.3 | 55.0 | 26.3 | 5.0 | 0 | 70.68 |

CT, threshold concentration.

A dose of 400 mg was given as a 1-h infusion q8h.

A 5-dose regimen (0 h, 36 mg/kg; 1.5 h, 33 mg/kg; 3.25 h, 23 mg/kg; 5 h, 16 mg/kg; 6.5 h, 12 mg/kg) was utilized. This regimen was repeated every 8 h over a 24-h period.

Furthermore, the concomitant administration of AZM at both doses tested (i.e., 10.5 mg/kg and 14 mg/kg) in combination with the SPR741 HSR did not alter the SPR741 profile (Fig. 4).

FIG 4.

Concentration-time profile of free SPR741 in plasma in the neutropenic thigh infection model in mice receiving two different human-simulated AZM regimens. Data are means ± standard deviations.

In vivo activity studies.

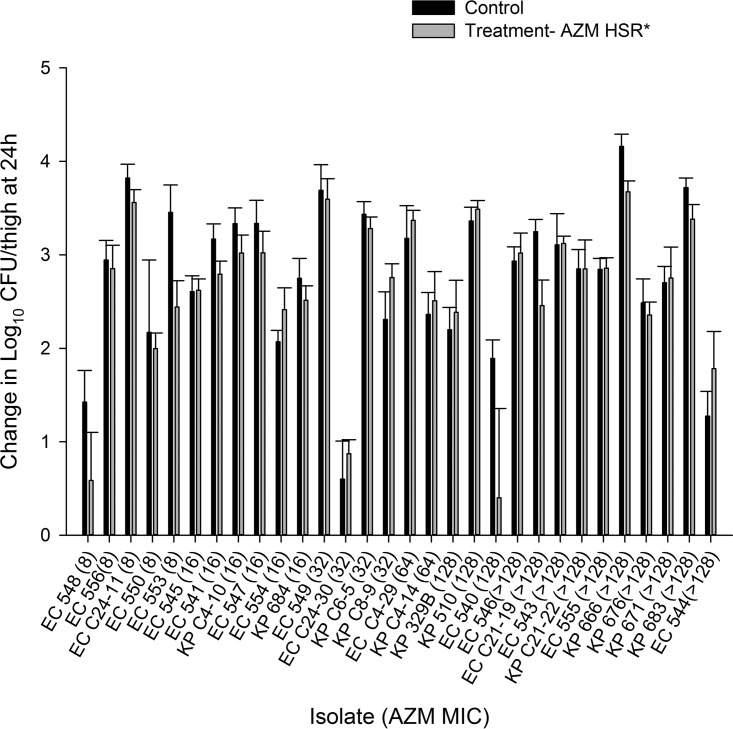

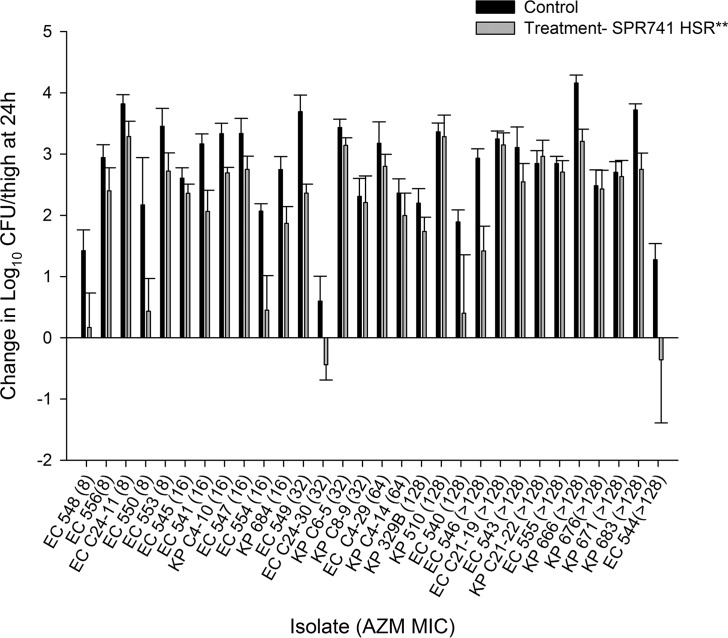

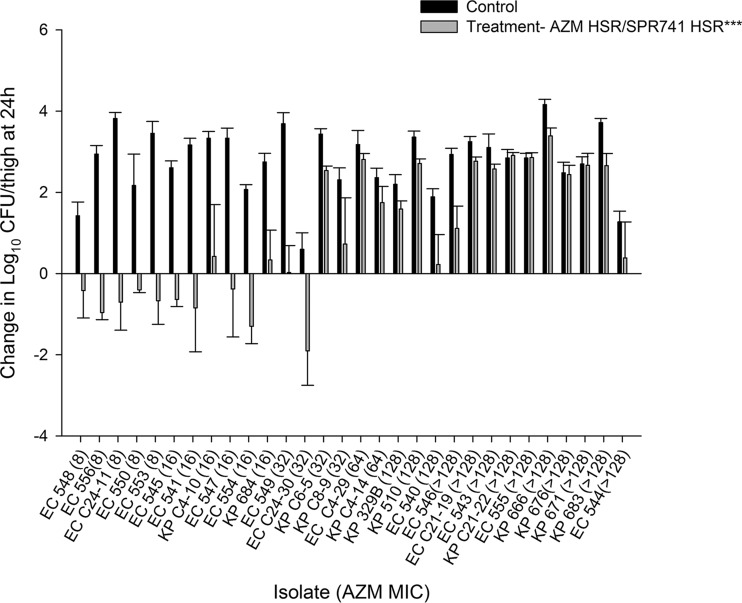

The results of the in vivo activity studies following administration of the AZM monotherapy, SPR741 monotherapy, and AZM-SPR741 combination HSRs for each of the 30 isolates are depicted in Fig. 5 to 7, respectively.

FIG 5.

Average changes in log10 CFU ± SD at 24 h from the starting inoculum in a neutropenic murine thigh model with an HSR of AZM monotherapy. Isolates are ordered by increasing MICs of AZM alone. *, HSR of AZM monotherapy (10.5 mg/kg).

FIG 6.

Average change in log10 CFU ± SD at 24 h from the starting inoculum in a neutropenic murine thigh model with human-simulated SPR741 monotherapy. Isolates are ordered by increasing MICs of AZM alone. **, SPR741 HSR consisting of 5 doses (0 h, 36 mg/kg; 1.5 h, 33 mg/kg; 3.25 h, 23 mg/kg; 5 h, 16 mg/kg; 6.5 h, 12 mg/kg) administered every 8 h over 24 h.

FIG 7.

Average change in log10 CFU ± SD at 24 h from the starting inoculum in a neutropenic murine thigh model with human-simulated AZM-SPR741. Isolates are ordered by increasing MICs of AZM alone. ***, AZM HSR (14 mg/kg) in combination with the SPR741 HSR of 5 doses (0 h, 36 mg/kg; 1.5 h, 33 mg/kg; 3.25 h, 23 mg/kg; 5 h, 16 mg/kg; 6.5 h, 12 mg/kg) administered every 8 h over 24 h.

The average log10 CFU/thigh at 0 h across all isolates was 5.80 ± 0.30. At 24 h, the bacterial burden increased by an average magnitude of 2.75 ± 0.85 log10 CFU/thigh in the untreated control mice. Treatment with the AZM HSR alone was associated with net growth of 2.60 ± 0.83 log10 CFU/thigh, while SPR741 alone was associated with net growth of 2.02 ± 1.17 log10 CFU/thigh. Treatment with the SPR741 HSR alone achieved stasis to 1-log kill relative to the starting inoculum in only 2/30 (6.7%) isolates. The changes in bacterial burdens relative to 0-h controls for the groups that received AZM alone, SPR741 alone, and the AZM-SPR741 combination were plotted against the AZM MIC for the isolates tested, as shown in Fig. 5 to 7, respectively. While the in vivo activity of the combination did not appear to be a function of either the SPR741 MIC alone or the resultant AZM-SPR741 MIC (data not shown), it did appear to correlate well with the isolates' susceptibilities to AZM (Fig. 7). Among isolates with AZM MICs of ≤16 mg/liter, treatment with AZM-SPR741 was associated with an average reduction in bacterial burden of −0.53 ± 0.82 log10 CFU/thigh, and stasis to 1-log kill relative to the starting inoculum was observed in 9/11 isolates (81.8%). In contrast, isolates with AZM MICs of ≥32 mg/liter displayed an average net growth of 1.80 ± 1.41 log10 CFU/thigh, and stasis to 1-log kill was achieved in 1/19 isolates (5.3%).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we observed in vitro potentiation by SPR741 when used in combination with AZM against clinical MDR Enterobacteriaceae isolates, including those expressing a wide array of β-lactamases (KPC, VIM, NDM, and ESBL) as well as isolates positive for macrolide-resistance genes. This diverse group of highly resistant isolates was chosen specifically to provide assurance of the robustness of the combination and the possibility of translation for application in the most challenging clinical scenarios. The potentiation by SPR741 observed herein is also consistent with previous in vitro findings. Corbett and colleagues conducted initial in vitro studies in order to describe the degree of potentiation by SPR741 in combination with a variety of previously approved agents against bacterial strains from the ATCC (7). Using a checkerboard methodology, the investigators demonstrated an effect exhibited by SPR741, achieving multifold reductions in fractional inhibitory concentrations (FIC). By use of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 as their primary test organism, as many as 13 of 35 agents were shown to reduce FIC by a factor of 32. Of note, particularly large reductions were observed among macrolide agents, including clarithromycin, erythromycin, and AZM (4,960-, 1,024- and 32-fold reductions, respectively). Although these results are suggestive of efficacy, confirmation of their applicability and translation in the context of in vivo studies is required. In vitro-in vivo discordances have been observed previously, and thus, efficacy cannot be reliably extrapolated based on in vitro data alone (10–12).

To date, in vivo data with SPR741 are limited. Initial studies conducted by Zurawski and colleagues were designed to demonstrate the efficacy of rifampin in combination with SPR741 against an extensively drug resistant (XDR) strain of Acinetobacter baumannii (AB5075) (9). The investigators utilized a previously established pulmonary infection model, administering doses of rifampin (5 mg/kg) and SPR741 (40 or 60 mg/kg) alone or in combination every 12 h. Survival at day 3 postinoculation was the preestablished primary endpoint. All untreated control animals, as well as those receiving SPR741 monotherapy, succumbed to infection. For those groups receiving monotherapy with rifampin, a 50% survival rate was observed. In contrast, 90% of mice receiving combination therapy with 60 mg/kg SPR741 survived (P < 0.0027). A statistically significant survival benefit was therefore demonstrated with combination therapy compared to monotherapy with the parent agent alone. Furthermore, bacterial density studies demonstrated a dose-response relationship which mirrored the survival rates observed. Relative to the growth in the 24-h control groups, combination therapy demonstrated a 6-log10 reduction in CFU per gram of lung tissue and a 2-log10 reduction with respect to SPR741 alone (P = 0.0029). These studies were important first steps toward a proof of concept for SPR741 as a potentiator of the in vivo activity of other antimicrobial agents. However, certain limitations were evident, as the systemic SPR741 exposures achieved with the utilized dosing regimens were unknown.

In the current study, HSRs of AZM, SPR741, and the combination were utilized to allow assessment of the in vivo activity of the agents examined in animals at clinically achievable exposures and to improve the translational application of the outcomes from preclinical studies into clinical practice. Interestingly, when we assessed in vivo activity, defined as a reduction in CFU as a function of either the SPR741 MIC alone or the resultant AZM-SPR741 MIC, no obvious delineation was observed over the MIC distribution. However, when the analysis was conducted using the MIC of AZM alone, the in vivo activity of the combination regimen appeared to be related to a concentration of 16 mg/liter. This observation is consistent with the mechanism of action for the combination, as AZM was primarily responsible for bacterial kill and may exert its effect only once it is allowed entry and access to the binding site on the large ribosomal subunit. Since AZM resistance genes influence the MIC, assessment of the genotypic profile may be predictive of potentiation by SPR741.

The HSR of the AZM-SPR741 combination showed promising in vivo activity against clinical MDR Enterobacteriaceae isolates. Bestowing activity on a macrolide by means of an antibiotic adjuvant provides an alternative method for circumventing enzyme-mediated resistance to β-lactams. Further studies with SPR741 combination therapy are warranted to elucidate its role in clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antimicrobial test agents.

An analytical-grade standard of SPR741 was utilized for in vitro and in vivo testing (lot 151015; Spero Therapeutics Inc., Cambridge, MA). An analytical-grade standard of AZM was used for in vitro testing (lot 036M4776V; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). For in vivo studies, commercial vials of AZM were purchased from Cardinal Health (Dublin, OH) (lot 6113162; Fresenius Kabi USA, Lake Zurich, IL). SPR741 drug stock solutions were reconstituted to a 25-mg/ml concentration with a sufficient volume of sterile 0.9% normal saline solution (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL). Subsequent dilutions in sterile 0.9% normal saline solution were made to attain final concentrations that would deliver the required doses based on the mean weight of the study population of mice. SPR741 was administered by subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of 0.2 ml. AZM in 500-mg vials was reconstituted with 4.8 ml sterile water for injection to yield stock concentrations of 100 mg/ml. Subsequent dilutions in sterile 0.9% normal saline solution were made to attain final concentrations that would deliver the required doses based on the mean weight of the study population of mice.

Bacterial isolates and in vitro susceptibility testing.

Thirty clinical MDR Enterobacteriaceae isolates, including 22 CRE, were selected from within the Center for Anti-Infective Research and Development library as well as the FDA-CDC Antimicrobial Resistance Isolate Bank (https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/resistance-bank/currently-available.html): 17 E. coli and 13 K. pneumoniae isolates. The MICs of AZM, SPR741, and the combination of AZM with SPR741 (determined using increasing concentrations of AZM and a fixed concentration of SPR741 at 8 mg/liter) were assessed for these 30 isolates in triplicate using the broth microdilution methodology (13). The fixed concentration of SPR741 was selected based on the previously conducted study showing high potentiation without intrinsic activity (7). For isolate MICs with the AZM-SPR741 combination, the control isolate ATCC EC 25922 (range, 0.063 to 0.25 mg/liter) was utilized. For SPR741 alone, both ATCC EC 25922 and BAA 747 (range, 64 to 128 mg/liter) were utilized. The modal MIC was used to characterize the isolates in the in vivo activity studies.

Animal infection model. (i) Laboratory animals.

Specific pathogen-free female ICR mice weighing 20 to 22 g were obtained from Envigo RMS, Inc. (Indianapolis, IN). The animals were allowed to acclimate for a minimum of 48 h before the commencement of experimentation and were provided food and water ad libitum. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Hartford Hospital. Mice were rendered transiently neutropenic by injecting cyclophosphamide intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a dose of 150 mg/kg of body weight at 4 days before inoculation and 100 mg/kg of body weight at 1 day before inoculation (15).

(ii) Neutropenic thigh infection model.

All isolates were previously frozen at −80°C in skim milk (BD BioSciences, Sparks, MD). Prior to the inoculation of mouse thighs, two transfers of the organism were performed onto Trypticase soy agar plates with 5% sheep blood (TSA II; Becton, Dickinson & Co., Sparks, MD), and the organism was incubated at 37°C for approximately 24 h. After an 18- to 24-h incubation of the second bacterial transfer, a bacterial suspension of approximately 107 CFU/ml was made for inoculation. Final inoculum concentrations were confirmed by serial dilution and plating techniques. The thigh infection was produced by intramuscular injection of 0.1 ml of the inoculum into each thigh (n = 2) of the mouse 2 h prior to the initiation of antimicrobial therapy.

AZM protein binding studies in mouse plasma.

The purpose of these studies was to evaluate the protein binding profile of AZM in mice. Protein binding studies were conducted in vivo in triplicate as follows. Mice were prepared as described under “Neutropenic thigh infection model” above. Two hours after bacterial inoculation, 12 mice (3 groups of 4 mice each) were administered one of the doses tested: 6.25 mg/kg, 12.5 mg/kg, or 25 mg/kg. One hour after dosing, mice were euthanized by CO2 exposure, followed by blood collection via intracardiac puncture and ultimately cervical dislocation. Blood samples from each group of mice (4 mice) were pooled in K2EDTA BD Microtainer tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). The blood was processed within 15 min of collection via centrifugation at 2,500 × g and 4°C for 10 min to separate the plasma. An aliquot of each of the pooled plasma samples was saved for total drug concentration determination. Three plasma aliquots of approximately 0.9 ml of each of the pooled plasma samples were transferred to three Centrifree ultrafiltration devices (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) with a 30,000-molecular-weight cutoff according to the manufacturer's recommendation and were centrifuged for 45 min at 4°C and 2,000 × g to generate an ultrafiltrate volume of approximately 250 μl. The resulting ultrafiltrates and aliquots of plasma were transferred to polypropylene tubes and were stored at −80°C until they were shipped on dry ice for analysis. Triplicate concentrations of compound in both the initial plasma solutions and ultrafiltrates were determined by AIT Bioscience (Indianapolis, IN). The protein binding of AZM at each dose administered was calculated using the following formula: % protein binding = 100 − (concentrationultrafiltrate/concentrationplasma × 100).

The average protein binding in mouse plasma was reported. Free (unbound) drug concentrations were incorporated into the determination of the human-simulated AZM regimen.

Pharmacokinetic studies. (i) Single-dose azithromycin and SPR741.

Single-dose pharmacokinetic studies were undertaken to identify the pharmacokinetic parameters of each agent, azithromycin and SPR741, when administered across a range of doses to infected ICR mice. Groups of infected mice (n = 36 per study) were administered either azithromycin at doses of 6.25, 12.5, or 25 mg/kg s.c. or SPR741 at doses of 12.5, 25, or 50 mg/kg s.c. Six mice were euthanized at six predefined time points. Terminal blood samples from CO2-asphyxiated mice were collected via cardiac puncture and placed in K2EDTA BD Microtainer tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Plasma was separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 10,000 × g and was then transferred to polypropylene tubes. These tubes were stored at −80°C until analysis. The plasma samples were shipped to AIT Bioscience for determination of azithromycin or SPR741 concentrations using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry techniques. The lower limit of quantification (LOQ) was 50 ng/ml. The pharmacokinetic exposure of SPR741 was estimated (WinNonlin, version 5.0.1; Pharsight Corp., Mountain View, CA) from these single-dose studies to assist in the prediction of a suitable human-simulated regimen. The ƒAUC0–24 for AZM was calculated by the trapezoidal rule for all doses utilized in the single-dose studies and was used to extrapolate the dose required to achieve the target exposure necessary for the HSR.

(ii) Human-simulated azithromycin and SPR741 exposures.

Pharmacokinetic studies for AZM and SPR741 were carried out to verify that the regimens selected provided exposures similar to those achieved in humans following the intravenous administration of 500 mg AZM q24h (14) and 400 mg SPR741 q8h (1-h infusion). The human dosing regimen of SPR741 was chosen by Spero Therapeutics based on phase I studies conducted in healthy volunteers (data on file, Spero Therapeutics). AZM and SPR741 human-simulated regimens were estimated using exposures derived from the single-dose pharmacokinetic studies of each agent after applying the protein binding percentage. The target exposure for AZM was based on the fAUC0–24 achieved in humans as reported in the package insert, the reported average percentage of protein binding by AZM in humans (7%), and the mouse protein binding estimated from the protein binding studies (14). The target human-simulated SPR741 exposure was based on the percentage of the dosing interval (in hours) during which the free drug concentrations remain above a fixed threshold concentration (%fT>CT) as well as the fAUC0–24 and utilized the data for the percentage of protein binding by SPR741 in humans and mice provided by Spero Therapeutics, Inc. (70% and 89% in humans and mice, respectively).

Prior to the conduct of the in vivo activity studies, confirmatory pharmacokinetic studies were undertaken to experimentally verify that the appropriate exposures were achieved for all compounds. Infected animals were administered the identified HSRs of AZM and SPR741. Groups of 6 mice were euthanized at 6 predefined time points. Terminal blood samples from CO2-asphyxiated mice were collected via cardiac puncture and were placed in K2EDTA BD Microtainer tubes (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Plasma was separated by centrifugation for 10 min at 4°C and 10,000 × g and was then transferred to polypropylene tubes. These tubes were stored at −80°C until analysis. The plasma samples were shipped to AIT Bioscience for determination of AZM and SPR741 concentrations.

In vivo activity of human-simulated AZM-SPR741 exposures.

The purpose of these studies was to assess the in vivo activity of the HSRs of AZM and SPR741 alone and in combination against a selection of Enterobacteriaceae isolates. In total, 30 clinical MDR isolates (17 E. coli and 13 K. pneumoniae isolates) with a broad range of test compound MICs were examined in the neutropenic murine model.

Mice were prepared and inoculated as described above and treatment was initiated 2 h later. The predetermined regimens were studied in groups of 3 mice over a 24-h treatment period. Control animals received the diluent vehicle in the same volume, route, and schedule as the most frequently dosed drug regimen. For each isolate tested, 3 untreated mice (6 thighs) were used as 0-h controls, 3 additional mice (receiving normal saline) were used as 24-h controls, 3 treatment mice were administered the AZM HSR, 3 treatment mice were administered the SPR741 HSR, and 3 treatment mice were administered the AZM-SPR741 combination HSR, for a total of 15 mice utilized for each isolate. After the 24-h treatment period, all animals were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation. After sacrifice, the thighs were removed and individually homogenized in normal saline. Serial dilutions were plated on an appropriate agar media for CFU enumeration. In vivo activity was calculated as the change in bacterial density obtained in treated mice after 24 h compared with the numbers in the starting control animals (time zero).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Safa Abuhussain, Tomefa Asempa, Lindsay Avery, Elizabeth Cyr, Sara Giovagnoli, Kimelyn Greenwood, Michelle Insignares, James Kidd, Alissa Padgett, Jennifer Tabor-Rennie, Debora Santini, Christina Sutherland, and Maham Tanveer of the Center for Anti-Infective Research and Development, Hartford, CT, for assistance with the conduct of the study.

This study was funded by Spero Therapeutics Inc. and was supported by the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs, through the Peer Reviewed Medical Research Program under award W81XWH-16-2-0019. Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the Department of Defense. In conducting research using animals, the investigators adhere to the laws of the United States and regulations of the Department of Agriculture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Magiorakos A-P, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacoby GA, Munoz-Price LS. 2005. The new beta-lactamases. N Engl J Med 352:380–391. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yılmaz GR, Baştuğ AT, But A, Yıldız S, Yetkin MA, Kanyılmaz D, Akıncı E, Bodur H. 2013. Clinical and microbiological efficacy and toxicity of colistin in patients infected with multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens. J Infect Chemother 19:57–62. doi: 10.1007/s10156-012-0451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ah YM, Kim AJ, Lee JY. 2014. Colistin resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Int J Antimicrob Agents 44:8–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delcour AH. 2009. Outer membrane permeability and antibiotic resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta 1794:808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbett D, Wise A, Langley T, Skinner K, Trimby E, Birchall S, Dorali A, Sandiford S, Williams J, Warn P, Vaara M, Lister T. 2017. Potentiation of antibiotic activity by a novel cationic peptide: potency and spectrum of activity of SPR741. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00200-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00200-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaara M, Siikanen Apajalathi O J, Fox J, Frimodt-Moller N, He H, Poudyal A, Li J, Nation RL, Vaara T. 2010. A novel polymyxin derivative that lacks the fatty acid tail and carries only three positive charges has strong synergism with agents excluded by the intact outer membrane. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3341–3346. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01439-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zurawski DV, Reinhart AA, Alamneh YA, Pucci MJ, Si Y, Abu-Taleb R, Shearer JP, Demons ST, Tyner SD, Lister T. 2017. SPR741, an antibiotic adjuvant, potentiates the in vitro and in vivo activity of rifampin against clinically relevant extensively drug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e01239-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01239-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stainton SM, Monogue ML, Nicolau DP. 2017. In vitro-in vivo discordance with humanized piperacillin-tazobactam exposures against piperacillin-tazobactam-resistant/pan-β-lactam-susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00491-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00491-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monogue ML, Nicolau DP. 2016. In vitro-in vivo discordance with humanized piperacillin-tazobactam exposures against piperacillin-tazobactam-resistant/pan-β-lactam-susceptible Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother; 60:7527–7529. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01208-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monogue ML, Abbo LM, Rosa R, Camargo JF, Martinez O, Bonomo RA, Nicolau DP. 2017. In vitro discordance with in vivo activity: humanized exposures of ceftazidime-avibactam, aztreonam, and tigecycline alone and in combination against New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a murine lung infection model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e00486-17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00486-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2017. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; seventeenth informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S17. CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sagent Pharmaceuticals. March 2013. Azithromycin intravenous package insert. Sagent Pharmaceuticals, Schaumburg, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maglio D, Banevicius MA, Sutherland C, Babalola C, Nightingale CH, Nicolau DP. 2005. Pharmacodynamic profile of ertapenem against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in a murine thigh model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 49:276–280. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.1.276-280.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]