Abstract

In Burkina Faso, flamed/grilled chickens are very popular and well known to consumers. The aim of this study was to evaluate the microbiological quality, the antibiotic resistance, and the virulence gene from Escherichia coli isolated from these chickens in Ouagadougou. A total of 102 grilled, flamed, and fumed chickens were collected in Ouagadougou and analyzed, using standard microbiological methods. All E. coli isolates were checked with the antimicrobial test and also typed by 16‐plex PCR. The mean of aerobic mesophilic bacteria (AMB) and thermo‐tolerant coliforms (TTC) was found respectively between 6.90 ± 0.12 × 107 CFU/g to 2.76 ± 0.44 × 108 CFU/g and 2.4 ± 0.82 × 107 CFU/g to 1.27 ± 0.9 × 108 CFU/g. E. coli strains were found to 27.45%. Forty samples (38.24%) were unacceptable based on the AMB load. Fifty‐nine samples (57.85%) were contaminated with TTCs. Low resistance was observed with antibiotics of betalactamin family. Diarrheagenic E. coli strains were detected in 21.43% of all samples. This study showed that flamed/grilled chickens sold in Ouagadougou could pose health risks for the consumers. Need of hygienic practices or system and good manufacturing practices is necessary to improve the hygienic quality of flamed/grilled chickens. Our results highlight the need of control of good hygiene and production practices to contribute to the improvement of the safety of the products and also to avoid antibiotic resistance. Slaughter, scalding, evisceration, plucking, bleeding, washing, rinsing, preserving, grilling, and selling may be the ways of contamination.

Keywords: antimicrobial resistance, Burkina Faso, diarrheagenic E. coli, grilled/flamed chickens, hygienic quality

1. INTRODUCTION

Microbial food safety is an increasing public health concern worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an important proportion of diarrhea in the world is of food origin (WHO 2013). More than 219,000 people die yearly in the world because of gastroenteritis due to lack of hygiene. Developing countries are the most affected by include cholera, campylobacteriosis, and infections to Escherichia coli, shigellosis, brucellosis, hepatitis A, and salmonellosis. Among the most appreciated street foods, meat products occupied a very good position. However, the poor sanitary practices during cooking and sale multiply the risk of microbial contamination. High ambient temperatures especially in tropical environments have been described as the major factors responsible for facilitating the access and multiplication of bacterial contaminants in meat products (Barro et al., 2006; Mankee et al., 2003). E. coli which is the first germ of fecal contamination indicators are responsible for several infections. In developing countries, the majority of the population treat these infections by self‐medication because of ignorance and refusal of cure. This practice is one of the causes of the emergence of antibiotic‐resistant bacteria (Rubin & Samore, 2002). In addition, the uncontrolled use of antibiotics in the livestock sector for animal diseases treatment and prevention as well as a growth promoters contribute to increase the spreading of antibiotic‐resistant bacteria (Kagambèga et al., 2013). Antimicrobials are valuable means to treat clinical diseases and keep healthy and growth promotion. However, the treatment of all herds and flocks with antimicrobials for increasing the growth and preventing illness has become an endless debate (Witte, 1998). Often whole flocks or herds of sick animals are treated at once, containing animals that are not sick. It is now generally accepted that the main risk factor for the increase in resistance to pathogenic bacteria is the anarchical use of antibiotics (Somda et al., 2017).

In Burkina Faso, more than 50,000 poultry are transported, killed, and consumed every day in Ouagadougou (DSMRA 2015). The hygiene often fails during slaughtering, scalding, evisceration, plucking, bleeding, washing, and rinsing, and increase the health risk associated with the consumption of this meat (Coulibaly, Bakayoko, & Karou, 2010). The aims of this study were to assess (1) microbiological quality of ready‐to‐eat chicken borne, (2) antibiotic resistance, and virulence genes of E. coli isolated in these chickens.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Samples collection

From September to December 2016, 102 chickens meats were collected from 102 producers in 59 sectors distributed on three crowns in Ouagadougou. These samples were composed of 66 grilled chickens (nine in crown 1, 28 in crown 2, and 27 in crown 3), 29 flamed chickens (two in crown 1, 18 in crown 2, and nine in crown 3), four fumed chickens (two in crown 1, two in crown 2, and 0 in crown 3), and three chickens prepared around fire (three in crown 1, 0 in crown 2, and 0 in crown 3). The samples were transported to the laboratory and kept at 4°C. The microbiological examination was started within the eight following hours.

All microbiological and molecular tests were carried out at Laboratoire National de Santé Pulique (LNSP) Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

2.2. Microbiological analysis

Twenty‐five grams of each meat sample (for chicken a mixture of meat from neck, breast, wings, and legs) was added into 225 ml of Buffered Peptone Water (Liofilchem, Teramo, Italy) and homogenized using a stomacher (400 Circulator; Seward, London, UK). Dilutions of 10 to 10 were realized from the stock solution according to ISO methods (ISO6887‐2 2004).

2.3. Aerobic mesophilic bacteria's enumeration

These microorganisms were enumerated on the plat count agar (PCA) medium according to the standard (ISO4833 2003). Briefly, 1 ml of each dilution was plated on PCA and incubated at 30°C for 72 ± 3 hr. The enumeration of the colonies was carried out on two successive dilution dishes (less than 300 colonies and more than 10 colonies on a dish). The results were expressed according to the standard (NFV08‐102 1998) using the following formula:

| (1) |

= the total of colonies counted on all the retained dishes of two successive dilutions and of which at least one dish contains 10 colonies; V = volume of inoculum applied to each dish in milliliters; n1 = dish number retained at the first dilution; n2 = dish number retained at the second dilution; 0.1 = dilution factor; d = dilution ratio corresponding to the first dilution retained.All the results were interpreted according to the standard (AFSSA 2007‐SA‐0174 2008). The threshold of detection of this germ was 108 CFU/g.

2.4. Thermo‐tolerant coliforms (E. coli) enumeration

Seeding was carried out in a double layer on violet red bile lactose agar and incubated at 44°C for 24 hr according to standard (NFV08‐053 2002). Bacteria were enumerated according to the formula described above. The threshold of detection of this germ was 102 CFU/g (AFSSA 2007‐SA‐0174 2008). After enumeration, two or three colonies were subcultured on Bromocresol purple agar and eosin methylene blue agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 hr. E. coli were characterized using API 20E system and isolated strains preserved at −30°C for antibiotic resistance test and molecular characterization.

2.5. Coagulase‐positive staphylococci enumeration

About 0.1 ml of the suspension was streaked on to the Baird Parker agar with egg yolk with potassium tellurite and carefully spread with a spreader (ISO6888‐2/A1 2003). Incubation was carried out at 37°C for 24–48 hr. All the dishes where there was growth of small black, shiny colonies surrounded by a transparent halo and an opaque border of 2–5 mm in diameter were retained to enumerate. The enumeration was carried out according to the formula described above. The threshold of detection of this germ was 103 CFU/g according to AFSSA 2007‐SA‐0174 (2008).

2.6. Salmonella characterization

Salmonella was tested for xylose lysine desoxycholate and Salmonella–Shigella (SS) agar medium according to ISO6579 (2002). The threshold of detection of this germ was 0 germ/25 g (AFSSA 2007‐SA‐0174 2008).

2.7. Antibiotic resistance test

All isolates were also tested for susceptibility to 14 different antimicrobial agents using the disk diffusion method on Mueller Hinton II agar (Bio‐Rad France), following the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines (EUCAST 2013). E. coli ATCC 25922 and ATCC 35218 were used as a control. The antimicrobial disks (Himedia, India) used were nalidixic acid (30 μg), ciprofloxacin (5 μg), ampicillin (10 μg), amoxicillin (25 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), imipenem (10 μg), tetracycline (30 μg), gentamicin (10 μg), chloramphenicol (30 μg), ceftriaxone (30 μg), norfloxacin (10 μg), ticarcillin (75 μg), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (30 μg), and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (25 μg). Inhibition diameters of the antibiotics were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Instructions (EUCAST 2013). The multiresistance is defined as the resistance to at least three different antibiotics families (Magiorakos et al., 2011).

2.8. 16‐plex PCR assay

The presence of STEC, EPEC, ETEC, EIEC, and EAEC on grilled chicken meat samples was detected by 16‐plex PCR for the genes uidA, pic, bfp, invE, hlyA, elt, ent, escV, eaeA, ipaH, aggR, stx1, stx2, estIa, estIb, and ast. The primers and PCR conditions were as previously described (Antikainen et al., 2009). The nucleotide sequences and predicted sizes of the amplified products for the specific oligonucleotide primers used in this study are shown in Table 1. The following criteria for identification of E. coli pathogroups were used: for STEC, the presence of stx1 and/or stx2 and possibly eaeA, escV, ent, and EHEC‐hly; for EPEC, the presence of eaeA and possibly escV, ent, and bfpB (the absence of bfpB indicated a EPEC); for ETEC, the presence of elt and/or estIa or estIb; for EIEC, the presence of invE and ipaH; and for EAEC, the presence of pic and/or aggR. For DNA extraction, a loopful of bacterial growth was taken from the first streaking area of the plate. It was suspended in 250 μl of sterile water in an Eppendorf tube, boiled at 100°C for 10 min and centrifuged.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for detection of the virulence genes

| Pathogroups | Genes | Sequences | bp | Concentration | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEC, EPEC | eae‐F | TCAATGCAGTTCCGTTATCAGTT | 482 | 0.1 | Vidal et al. (2005) |

| eae‐R | GTAAAGTCCGTTACCCCAACCTG | ||||

| escV‐F | ATTCTGGCTCTCTTCTTCTTTATGGCTG | 544 | 0.4 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| escV‐R | CGTCCCCTTTTACAAACTTCATCGC | ||||

| ent‐F | TGGGCTAAAAGAAGACACACTG | 629 | 0.4 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| ent‐R | CAAGCATCCTGATTATCTCACC | ||||

| Typical EPEC | bfpB‐F | GACACCTCATTGCTGAAGTCG | 910 | 0.1 | Müller et al. (2007) |

| bfpB‐R | CCAGAACACCTCCGTTATGC | ||||

| STEC | hlyEHEC‐F | TTCTGGGAAACAGTGACGCACATA | 688 | 0.1 | Antikainen et al. (2009) |

| hlyEHEC‐R | TCACCGATCTTCTCATCCCAATG | ||||

| stx1A‐F | CGATGTTACGGTTTGTTACTGTGACAGC | 244 | 0.2 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| stx1A‐R | AATGCCACGCTTCCCAGAATTG | ||||

| stx2A‐F | GTTTTGACCATCTTCGTCTGATTATTGAG | 324 | 0.4 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| stx2A‐R | AGCGTAAGGCTTCTGCTGTGAC | ||||

| EIEC | ipaH‐F | GAAAACCCTCCTGGTCCATCAGG | 437 | 0.1 | Antikainen et al. (2009) |

| ipaH‐R | GCCGGTCAGCCACCCTCTGAGAGTAC | 0.1 | Brandal et al. (2007) | ||

| invE‐F | CGATAGATGGCGAGAAATTATATCCCG | 766 | 0.2 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| invE‐R | CGATCAAGAATCCCTAACAGAAGAATCAC | ||||

| EAEC | aggR‐F | ACGCAGAGTTGCCTGATAAAG | 400 | 0.2 | Müller et al. (2007) |

| aggR‐R | AATACAGAATCGTCAGCATCAGC | ||||

| pic‐F | AGCCGTTTCCGCAGAAGCC | 1,111 | 0.2 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| pic‐R | AAATGTCAGTGAACCGACGATTGG | ||||

| astA‐F | TGCCATCAACACAGTATATCCG | 102 | 0.4 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| astA‐R | ACGGCTTTGTAGTCCTTCCAT | ||||

| ETEC | LT‐F | GAACAGGAGGTTTCTGCGTTAGGTG | 655 | 0.1 | Müller et al. (2007) |

| LT‐R | CTTTCAATGGCTTTTTTTTGGGAGTC | ||||

| STIa‐F | CCTCTTTTAGYCAGACARCTGAATCASTTG | 157 | 0.4 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| STIa‐R | CAGGCAGGATTACAACAAAGTTCACAG | ||||

| STI‐F | TGTCTTTTTCACCTTTCGCTC | 171 | 0.2 | Müller et al. (2007) | |

| STI‐R | CGGTACAAGCAGGATTACAACAC | ||||

| E. coli | uidA‐F | ATGCCAGTCCAGCGTTTTTGC | 1,487 | 0.2 | Müller et al. (2007) |

| uidA‐R | AAAGTGTGGGTCAATAATCAGGAAGTG |

STEC, Shiga toxin‐producing E. coli; EPEC, enteropathogenic E. coli; EIEC, enteroinvasive E. coli; EAEC, enteroaggregative E. coli; ETEC, enterotoxigenic E. coli.

PCR was performed in a reaction of 20 μl containing 2.5 μl 10× PCR buffer (Solis Biodyne), 0.75 μl dNTPs (10 mmol/L), 0.25 μl MgCl2 (50 mmol/L), 0.2 μl Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μl), and 0.5 μl of each mixture of the 16 primer pairs at the concentrations listed in Table 1; 12.8 μl of PCR‐grade water and 2.5 μl of DNA sample were added to bring the final volume to 10 μl. The cycling conditions used in the thermal cycler (Applied Biosystem, 2720 thermal cycler, Singapore) were 98°C for 30 s, 35 cycles of 98°C for 30 s, 63°C for 60 s, and 72°C for 90 s with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

The amplified PCR products were separated by agarose gel (1.5% w/v) electrophoresis and visualized under UV light (Bioblock Scientific, Illkirch, CEDEX) after staining with ethidium bromide. Reference strains RHE 4283 (E 2348/69) for EPEC, FE94725 (Burkina Faso, beef) for ETEC, FE102301 (Burkina Faso, beef) for STEC, RHE 6647 (145‐46‐215, Statens Serum Institut [SSI], Copenhagen, Denmark) for EIEC, IH 56822 (patient isolate (Keskimäki, Mattila, Peltola, & Siitonen, 2000), for EAEC, and FE95562 (Burkina Faso, beef) for STEC‐ETEC were included in each PCR run. All the 16‐plex PCR positive results were confirmed by single PCRs.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Microbiological analysis

The average loads of various microorganisms determined are summarized in Table 2. The average loads of aerobic mesophilic bacteria (AMB) and thermo‐tolerant coliforms (TTCs; including E. coli) varied respectively between 6.90 ± 0.12 × 107 CFU/g to 2.76 ± 0.44 × 108 CFU/g and 2.4 ± 0.82 × 107 CFU/g to 1.27 ± 0.9 × 108 CFU/g. No Salmonella ssp. and Staphylococcus‐positive coagulase were found. According to the AFSSA 2007‐SA‐0174 standard referring to the load of the AMB, about 38.24% (40/102, including 25 grilled chickens, 11 flamed chickens, and four fumed chickens) of the analyzed samples were unacceptable (superior to 108 CFU/g) (Table 3). About 57.85% (59/102, including 36 grilled chicken, 16 flamed chickens, four fumed chickens, and three chickens around the fire) of the samples were unacceptable (superior to 102 CFU/g) according to their load of TTCs (Table 3). E. coli were found in 27.45% (28/102 including 20 in grilled chickens, seven in broiler chickens, and one in fumed chicken) of the samples analyzed, as shown in Table 3. In addition to E. coli, others pathogens including Klebsiella spp. (in one sample), Pantoea spp. (in eight samples), Serratia ficaria (in two samples), and Kluyera spp. (in two samples) were isolated in 12.75% (13/102 samples). Six were contaminated with both E. coli and others pathogens, while in single‐sample chickens, one was both contaminated with E. coli and Pantoea spp.

Table 2.

The average loads of the various microorganisms

| Products | Grilled chicken (n = 66) | Flamed chicken (n = 29) | Fumed chicken (n = 4) | Chickens around the fire (n = 3) | Total (n = 102) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB (108 CFU/g) | 1.03 ± 1.36 | 1.09 ± 1.36 | 2.76 ± 0.44 | 0.690 ± 0.115 | 1.12 ± 1.4 |

| TTC (108 CFU/g) | 0.24 ± 0.82 | 0.28 ± 0.86 | 1.27 ± 0.9 | 0.934 ± 1.61 | 0.32 ± 0.87 |

AMB, aerobic mesophilic bacteria; TTC, thermo‐tolerant coliforms; CFU/g, colony‐forming unit per gram; n, number.

Table 3.

Contamination frequency of different chickens analyzed

| Products | Grilled chicken n = 66 (%) | Flamed chicken n = 29 (%) | Fumed chicken n = 4 (%) | Chickens around the fire n = 3 (%) | Total n = 102 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB > 108 CFU/g | 25 (38) | 11 (38) | 4 (100) | 0 | 40 (38.24) |

| TTC | 36 (55) | 16 (55) | 4 (100) | 3 (100) | 59 (57.85) |

| E. coli | 20 (30) | 7 (24) | 1 (25) | 0 | 28 (27.45) |

| Salmonella spp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others bacteria | 10 (15) | 3 (10) | 0 | 0 | 13 (12.75) |

| E. coli + others bacteria | 6 (9) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 7 (6.86) |

AMB, aerobic mesophilic bacteria; TTC, thermo‐tolerant coliforms; E. coli, Escherichia coli; CFU/g, colony‐forming unit per gram; n, number; %, percentage.

Others bacteria: Enterobacter sakazakii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klyvera spp., Pantoea spp., Serratia ficaria.

3.2. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of griller/flamed chickens isolates

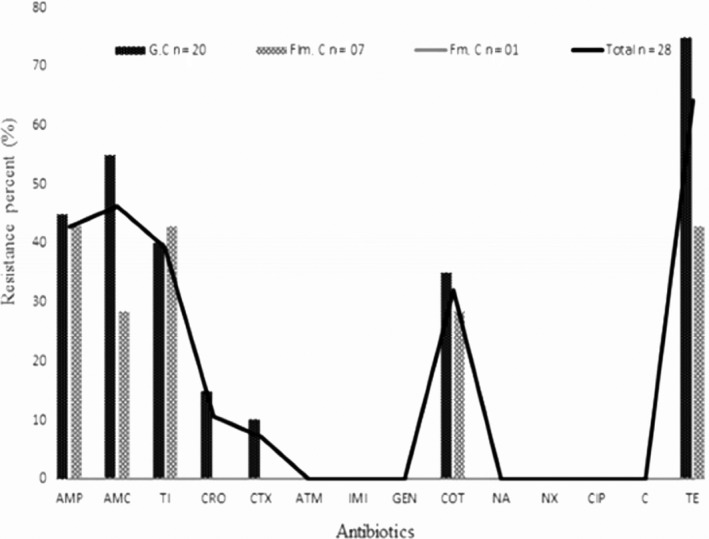

Globally, the E. coli isolated from fumed, grilled, and flamed chickens showed a low resistance to antibiotic teste. All isolates were sensitive to imipenem, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, norfloxacin, gentamicin, aztreonam, and chloramphenicol. However, resistance was observed with cefotaxime (7.14%), ceftriaxone (10.71%), sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim (32.14%), ticarcillin (39.3%), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (46.43%), ampicillin (42.86%), and tetracycline (64.3%) (Figure 1). Twenty‐one percent (6/28) of tested strains were extended‐spectrum‐beta‐lactam (ESBL) positives.

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli strains isolated from grilled/flamed chicken meat. AMP, ampicillin; ATM, aztreonam; AMC, amoxicillin/clavulanate; CRO, ceftriaxone; CTX, cefotaxime; NX, norfloxacin; COT, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole; C, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; GEN, gentamicin; IMI, imipenem; NA, nalidixic acid; TE, tetracycline; TC, ticarcillin; %, percentage; n, number; G.C, grilled chicken; Flm.C, flamed chicken; Fm.C, fumed chicken

3.3. Diarrheagenic E. coli characterization

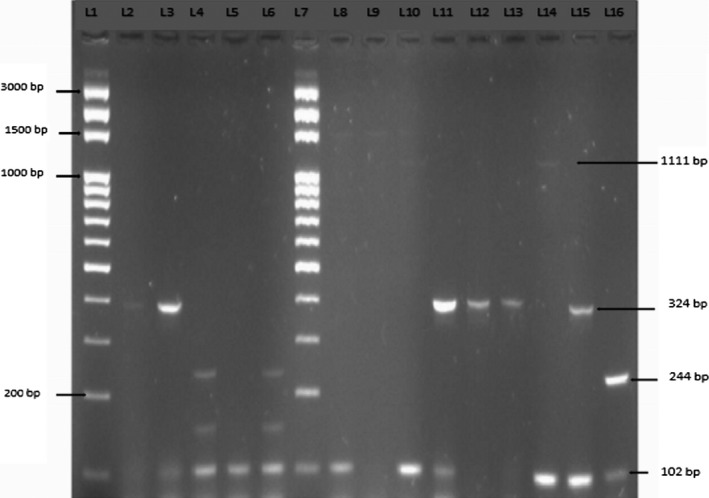

16‐plex PCR was used to detect virulence genes carried by diarrheagenic E. coli and to classify the strains as STEC, EPEC, ETEC, EIEC, or EAEC. Diarrheagenic E. coli were detected in 21.43% (6/28) of all samples. Only STIa, stx2A, invE, astA, and aggR virulence genes were detected (Table 4). The six detected diarrheagenic E. coli were as follows: EAEC and ETEC (in two samples each) and STEC and EIEC (in one sample each) (Figure 2). No EPEC was detected. According to the nature of samples (grilled chickens, flamed chickens, and fumed chickens), prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli (DEC) was 20% (4/20), 28.57% (2/7) from grilled chickens and flamed chickens, respectively.

Table 4.

Virulence genes detected by 16‐plex PCR of Escherichia coli strains isolated in grilled/flamed chicken meat

| DEC pathovars | Virulence genes | Grilled chicken (n = 20) | Flamed chicken (n = 7) | Fumed chicken (n = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEC (n = 1) | Stx2A | + | – | – |

| EAEC (n = 2) | asta, aggR | – | + | – |

| EIEC (n = 1) | invE | + | – | – |

| ETEC (n = 2) | STIa | + | – | – |

| Total n = 6 (%) | 4 (20) | 2 (28.57) | 0 |

DEC, Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli; n, number; %, percent; +, presence; –, absence.

Figure 2.

Example of the 16‐plex PCR results to DEC isolated from grilled/flamed chicken. L1 = marker, L2 = RHE6647 (EIEC), L3 = IHE56822 (EAEC), L4 = FE102301 (STEC), L5 = FE94725 (ETEC), L6 = FE95562 (STEC‐ETEC), L7 = marker, L8 = G.C2, L9 = G.C6, L10 = G.C9, L11 = G.C12, L12 = G.C34, L13 = G.C38, L14 = G.C60, L15 = Flm.C27, L16 = Flm.C28

4. DISCUSSION

According to Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), the risk of food poisoning associated with street food remains a threat in many parts of the world, with microbiological contamination being one of the major problems. It is recognized that food‐borne pathogens represent a serious health hazard, with the risk mainly depending on the type of food and the way of cooking and conservation. The ignorance of street sellers as the cause of food‐borne illnesses is a risk factor that cannot be ignored (FAO 2007). To our knowledge, this is the first study about E. coli in flamed, grilled, and fumed chicken meat. The results of the microbiological analyses of flamed, grilled, and fumed chicken meat showed the highest load in both AMB (threshold value for contamination superior to 108 CFU/g) and TTCs. E. coli are the first germs of fecal contamination indicators. The presence of E. coli and AMB is an indicator of lack of hygiene in production process. As the chickens are flamed or grilled, some questions like the route of contamination remain and need to be addressed. This hygienic issue may be due to the possible contamination of chickens since the abattoir, and/or during the process of chickens grilling and/or postprocessing contamination due to unhygienic sales environment and handling of grilled chickens. Consequently, the consumption of these contaminated products could be a public health risk for consumers. Previous studies in West Africa have showed contamination of fresh chicken meat and offals by AMBs and TTCs (Attien et al., 2013; Ilboudo, Savadogo, Samandoulougou, & Abre, 2016). Otherwise, these studies have shown that the conditions for slaughter, scalding, evisceration, plucking, bleeding, washing, rinsing, preserving, grilling, and selling may be the ways of contamination. These failures of the hygiene rules are generally the cause of the contamination of fresh meat. The contamination could be also at the level of the sale material, the seller himself, and also the quality of the grilling (insufficient time of grilling) as stated some researchers (Khallaf et al., 2014). Our survey results showed that during the grilling process, some others sellers used dirty water to reduce fire intensity when it is high. The charcoal used for grilling could also be the source of the contamination because the conditions of production of the charcoal do not obey the rules of hygiene. In addition, others sellers were alone and were at the same time responsible for the whole chain of meat production. They slaughtered the chickens, scalded them, eviscerated them, plucked them, washed them, preserved them, burned them, and even received the money. These practices could increase the risk of contamination of meat at the end of production. Barro et al. (2006) and Gedik, Voss, and Voss (2013) showed that money handling constitutes another risk factor of street foods contamination. Money can get contaminated and may thus play a role in the transmission of microorganisms to other people, during the selling.

No Salmonella and Staphylococcus coagulase positive were found in this study. However, others studies notified the presence of these bacteria in fresh poultry meat (Attien et al., 2013; Kagambèga et al., 2013; Khallaf et al., 2014; Nzouankeu, Ngandjio, Ejenguele, Njine, & Wouafo, 2010).

Our results showed that the great majority of E. coli isolates from grilled/fumed chicken were susceptible to ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, norfloxacin, nalidixic acid, aztreonam, imipenem, and gentamicin. However, resistance was observed to antibiotics of betalactamin family such as ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, ticarcillin cefotaxime, and others families such as tetracycline and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. ESBL was found in six strains. Antimicrobials are used in the absence of illness to prevent diseases when animals are susceptible to infection (Turtura, Massa, & Ghazvinizadeh, 1990). This practice is very usual in developing countries where outbreak is caused by enteric pathogens which are the sources of farms poultry diseases. Our results were in agreement with previous studies realized on fresh and broiler meat chickens in Canada, Spain, in Iran (Cortés et al., 2010; Vincent et al., 2010). In slaughterhouse, resistant strains from the gastrointestinal tract may infect chicken carcasses and, as a result, chicken meats are often related to multiresistant E. coli. Also, eggs become infected during laying (Reza, Mehdi, Faham, & Mohammad, 2014). Therefore, antimicrobial‐resistant fecal E. coli from poultry can infect humans directly and indirectly with food. Though seldom, these resistant bacteria may colonize in the human gastrointestinal tract and may also transfer resistance bacteria to human endogenous flora (Reza et al., 2014).

In Burkina Faso, chicken meat is very popular, but production conditions are very poor and could lead to diarrheal diseases to consumers. The present study was the first conducted in Burkina Faso to detect diarrheagenic E. coli based on the presence of the virulence genes in bacterial cultures derived from grilled/flamed chickens. In 2012, a similar study was conducted by Kagambega et al. (2012) in beef, mutton, and fresh chicken meat. They showed that EPEC, ETEC, and EAEC were detected less often than STEC in beef and mouton meat and intestine samples, except in chickens, which seem to be the major carriers of atypical EPEC. However, the present study carried out on grilled/flamed chickens showed that ETEC and EAEC were detected each on two strains but STEC and EIEC were detected each on one strain. No EPEC is detected in our study. However, EPEC was detected in similar studies conducted in others countries (Farooq, Hussain, Mir, Bhat, & Wani, 2009; Nzouankeu et al., 2010). E. coli strains as STEC can be transmitted via the fecal‐oral route and contamination often occurs through the ingestion of contaminated food or water, direct contact with animals, interhumans, or contaminated objects, or more rarely by inhalation (Crump et al., 2002; Grant et al., 2008). Presence of the DEC in grilled/flamed chicken meat refect poor food hygiene and the common occurence of potential pathogens from human in Burkina Faso. Hygiene rules must be applied strictly to the slaughterhouse and in the sale outlets to avoid contamination of grilled/flamed meat by DEC.

Our study showed that most of our samples analyzed contain amounts of germs that exceed the acceptable limits to the standards established for both mesophilic aerobic total flora, fecal coliforms, and diarrheagenic E. coli pathogroups. It is necessary to set up good hygienic practices in the production of grilled, fumed, and flamed chickens to ensure the quality of finished products. In addition, intervention strategies, such as promoting hand washing with soap and good hygienic practices at the slaughterhouses and sales outlets, can have a sound practical impact on public health.

5. CONCLUSION

This study shows also the emergence of betalactamin resistance to E. coli isolates in grilled, fumed, and flamed chickens. The resistance of E. coli to betalactamins highlights the need for the establishment of a network and continuous monitoring of antibiotic resistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the ARES for funding this study through the project Qualisani and the Laboratoire National de Santé Publique/Burkina Faso for laboratory facilities provided.

Somda NS, Bonkoungou OJI, Zongo C, et al. Safety of ready‐to‐eat chicken in Burkina Faso: Microbiological quality, antibiotic resistance, and virulence genes in Escherichia coli isolated from chicken samples of Ouagadougou. Food Sci Nutr. 2018;6:1077–1084. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.650

REFERENCES

- AFSSA 2007‐SA‐0174 (2008). Avis de l'AFSSA concernant les références applicables aux denrées alimentaires en tant que critères indicateurs d'hygiène des procédés. AFSSA saisie 2007‐SA‐0174.

- Antikainen, J. , Tarkka, E. , Haukka, K. , Siitonen, A. , Vaara, M. , & Kirveskari, J. (2009). New 16‐plex PCR method for rapid detection of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli directly from stool samples. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 28(8), 899–908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-009-0720-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attien, P. , Sina, H. , Moussaoui, W. , Dadié, T. , Djéni, T. , Bankole, H. , … Baba‐Moussa, L. (2013). Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus strains isolated from meat products sold in Abidjan streets (Ivory Coast). African Journal of Microbiology Research, 7(26), 3285–3293. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJMR [Google Scholar]

- Barro, N. , Bello, A. R. , Savadogo, A. , Ouattara, C. A. T. , IIboudo, A. , & Traore, A. S. (2006). Hygienic status assessment of dish washing waters, utensils, hands and pieces of money from street food processing sites in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). African Journal of Biotechnology, 5(11), 1107–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Brandal, L. T. , Lindstedt, B.‐A. , Aas, L. , Stavnes, T.‐L. , Lassen, J. , & Kapperud, G. (2007). Octaplex PCR and fluorescence‐based capillary electrophoresis for identification of human diarrheagenic Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. Journal of Microbiol Methods, 68(2), 331–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2006.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, P. , Blanc, V. , Mora, A. , Dahbi, G. , Blanco, J. E. , Blanco, M. , … Alonso, M. P. (2010). Isolation and characterization of potentially pathogenic antimicrobial‐resistant Escherichia coli strains from chicken and pig farms in Spain. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 76(9), 2799–2805. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02421-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulibaly, E. , Bakayoko, S. , & Karou, T. (2010). Sérotypage et antibiorésistance des souches de Salmonella isolées dans les foies de poulets vendus sur les marchés de Yopougon (Abidjan Côte d'Ivoire) en 2005. Revue Africaine de Santé et de Production Animale, 8(S), 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Crump, J. A. , Sulka, A. C. , Langer, A. J. , Schaben, C. , Crielly, A. S. , Gage, R. , … Toney, D. M. (2002). An outbreak of Escherichia coli O157: H7 infections among visitors to a dairy farm. The New England Journal of Medicine, 347(8), 555–560. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DSMRA (2015). Données statistiques du secteur de l’élévage au Burkina Faso en 2011. Ann. statistique Ministère des Ress. Animales. 151 p. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST (2013). Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. 18 p.

- FAO (2007). Les bonnes pratiques d'hygiène dans la préparation et la vente des aliments de rue en Afrique: Outils pour la formation. ISSN, 188. https://doi.org/92-5-205583-5

- Farooq, S. , Hussain, I. , Mir, M. , Bhat, M. , & Wani, S. (2009). Isolation of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Shiga toxin 1 and 2f‐producing Escherichia coli from avian species in India. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 48(6), 692–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gedik, H. , Voss, T. A. , & Voss, A. (2013). Money and transmission of bacteria. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, 2(1), 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/2047-2994-2-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, J. , Wendelboe, A. M. , Wendel, A. , Jepson, B. , Torres, P. , Smelser, C. , & Rolfs, R. T. (2008). Spinach‐associated Escherichia coli O157: H7 outbreak, Utah and New Mexico, 2006. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 14(10), 1633 https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1410.071341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilboudo, A. J. , Savadogo, A. , Samandoulougou, S. , & Abre, M. (2016). Qualite bactériologique des carcasses de viandes porcines et bovines produites a l'abattoir de ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Revue de Microbiologie Industrielle Sanitaire et Environnementale, 10(1), 33–55. [Google Scholar]

- ISO4833 (2003). Méthode horizontale pour le dénombrement des micro‐organismes. V08‐011, 1–9.

- ISO6579 (2002). Méthode horizontale pour la recherche de Salmonella spp. 08‐013, 1–26.

- ISO6887‐2 (2004). Préparation des échantillons, de la suspension mère et des dilutions écimales en vue de l'examen microbiologique. V08‐010‐2, 16.

- ISO6888‐2/A1 (2003). Microbiologie des aliments. Méthode horizontale pour le dénombrement des staphylocoques à coagulase positive (Staphylococcus aureus et autres espèces). Partie 2: Technique utilisant le milieu gélosé au plasma de lapin et au fibrinogène. Amendement 1: Inclusion des données de fidélité. NF EN, V 08‐014‐2/A1.

- Kagambèga, A. , Lienemann, T. , Aulu, L. , Traoré, A. S. , Barro, N. , Siitonen, A. , & Haukka, K. (2013). Prevalence and characterization of Salmonella enterica from the feces of cattle, poultry, swine and hedgehogs in Burkina Faso and their comparison to human Salmonella isolates. BMC Microbiology, 13(1), 253 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagambega, A. , Martikainen, O. , Lienemann, T. , Siitonen, A. , Traore, A. S. , Barro, N. , & Haukka, K. (2012). Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli detected by 16‐plex PCR in raw meat and beef intestines sold at local markets in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 153(1), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keskimäki, M. , Mattila, L. , Peltola, H. , & Siitonen, A. (2000). Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Finns with or without diarrhea during a round‐the‐world trip. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 38(12), 4425–4429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khallaf, M. , Benbakhta, B. , Nasri, I. , Sarhane, B. , Senouci, S. , & Ennaji, M. (2014). Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from chicken meat marketed in Rabat, Morocco. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 7(4), 1665–1670. [Google Scholar]

- Magiorakos, A. , Srinivasan, A. , Carey, R. , Carmeli, Y. , Falagas, M. , Giske, C. , … Monnet, D. (2011). Multidrug resistant, extensively drug‐resistant and pandrug‐resistant bacteria: An international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 18(3), 268–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mankee, A. , Ali, S. , Chin, A. , Indalsingh, R. , Khan, R. , Mohammed, F. , … Simeon, D. (2003). Bacteriological quality of “doubles” sold by street vendors in Trinidad and the attitudes, knowledge and perceptions of the public about its consumption and health risk. Food Microbiology, 20(6), 631–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-0020(03)00032-7 [Google Scholar]

- Müller, D. , Greune, L. , Heusipp, G. , Karch, H. , Fruth, A. , Tschäpe, H. , & Schmidt, M. A. (2007). Identification of unconventional intestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates expressing intermediate virulence factor profiles by using a novel single‐step multiplex PCR. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 73(10), 3380–3390. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02855-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NFV08‐053 (2002). Microbiologie des aliments: Méthode horizontale pour le dénombrement des Escherichia coli β‐glucuronidase positive par comptage des colonies à 44°C au moyen du 5‐bromo‐4‐chloro‐3‐indolyl β‐D‐glucoronide Méthode de routine.

- NFV08‐102 (1998). Microbiologie des aliments: Règles pour le comptage des colonies et pour l'expression des résultats cas des dénombrements sur milieu solide.

- Nzouankeu, A. , Ngandjio, A. , Ejenguele, G. , Njine, T. , & Wouafo, M. N. (2010). Multiple contaminations of chickens with Campylobacter, Escherichia coli and Salmonella in Yaounde (Cameroon). Journal of Infection in Developing Countries, 4(9), 583–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza, T. , Mehdi, K. , Faham, K. , & Mohammad, R. F. (2014). Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance of Escherichia coli isolated from chickens in Iran. Veterinary Medicine International, 2014, 491418 https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/491418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A. , & Samore, R. (2002). Eclosions attribuables à Escherichia coli multi résistant aux antibiotiques dans les établissements de soins de longue durée des régions de Durham, York, Toronto et Ontario. Relevé des Maladies Transmissibles au Canada, 28, 113–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somda, N. S. , Traoré, O. , Bonkoungou, O. J. I. , Bassolé, I. H. N. , Traoré, Y. , Barro, N. , & Savadogo, A. (2017). Serotyping and antimicrobial drug resistance of Salmonella isolated from lettuce and human diarrhea samples in Burkina Faso. African Journal of Infectious Diseases, 11(2), 024–030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turtura, G. C. , Massa, S. , & Ghazvinizadeh, H. (1990). Antibiotic resistance among coliform bacteria isolated from carcasses of commercially slaughtered chickens. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 11(3–4), 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1605(90)90029-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, M. , Kruger, E. , Durán, C. , Lagos, R. , Levine, M. , Prado, V. , … Vidal, R. (2005). Single multiplex PCR assay to identify simultaneously the six categories of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli associated with enteric infections. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 43(10), 5362–5365. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.43.10.5362-5365.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, C. , Boerlin, P. , Daignault, D. , Dozois, C. M. , Dutil, L. , Galanakis, C. , … Ziebell, K. (2010). Food reservoir for Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infections. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 16(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/www.cdc.gov/eid [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2013). Infections à Salmonella (non typhiques). Aide‐mémoire. 139 p. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs139/fr/

- Witte, W. (1998). Medical consequences of antibiotic use in agriculture. Science, 279(5353), 996–997. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5353.996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]