Abstract

Gastric cancer (GC) remains one of the most common and malignant types of cancer due to its rapid progression, distant metastasis, and resistance to conventional chemotherapy, although efforts have been made to understand the underlying mechanism of this resistance and to improve clinical outcome. It is well recognized that tumor heterogeneity, a fundamental feature of malignancy, plays an essential role in the cancer development and chemoresistance. The model of tumor-initiating cell (TIC) has been proposed to explain the genetic, histological, and phenotypical heterogeneity of GC. TIC accounts for a minor subpopulation of tumor cells with key characteristics including high tumorigenicity, maintenance of self-renewal potential, giving rise to both tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic cancer cells, and resistance to chemotherapy. Regarding tumor-initiating cell of GC (GATIC), substantial studies have been performed to (1) identify the putative specific cell markers for purification and functional validation of GATICs; (2) trace the origin of GATICs; and (3) decode the regulatory mechanism of GATICs. Furthermore, recent studies demonstrate the plasticity of GATIC and the interaction between GATIC and its surrounding factors (TIC niche or tumor microenvironment). All these investigations pave the way for the development of GATIC-targeted therapy, which is in the phase of preclinical studies and clinical trials. Here, we interpret the heterogeneity of GC from the perspectives of TIC by reviewing the above-mentioned fundamental and clinical studies of GATICs. Problems encountered during the GATIC investigations and the potential solutions are also discussed.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Tumor heterogeneity, Tumor-initiating cell

Core tip: Gastric cancer (GC) remains a severe malignancy with high incidence and mortality rates. One major underlying mechanism of GC rapid progression, extensive spreading, and chemoresistance is tumor heterogeneity could be explained by the gastric tumor-initiating cell (GATIC). Since the initial identification of putative GATICs in 2007, substantial studies have been performed to investigate various aspects of GATICs. Here, we systemically discuss the tumor heterogeneity of GC from the view of GATICs by reviewing studies on the identification and validation of GATICs, origination of GATICs, plasticity of GATICs and its underlying mechanism, and current status of chemotherapeutic agents targeting GATICs.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric cancer (GC), with gastric adenocarcinoma as the most common histological type, is the fifth most common malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide[1]. Despite its declining incidence and mortality rate in several developed countries, GC remains a common and deadly disease with a poor prognosis globally, especially in northeastern Asia and South America[2]. Although significant progress has been made regarding the development of anti-cancer therapeutic agents, chemoresistance and recurrence of GC are major obstacles for improving the overall survival rate of advanced GC patients[3]. Combined chemotherapy, such as fluoropyrimidine plus platinum derivatives, serves as the first-line treatment for patients with locally advanced or metastatic GC. Unfortunately, response rate of these patients to these major regimens is only approximately 50%, with overall survival ranging from 7 to 11 mo. For patients with relapsed GC, second-line treatment confers limited benefits of less than 6 mo[4,5]. With the advance of new techniques, especially high-throughput sequencing of GC patients’ primary tumor materials, even at the single cell level, investigators have revealed the essential roles of tumor heterogeneity underlying the mechanism of tumor recurrence and drug resistance[6].

Tumor heterogeneity is universally recognized as one of most fundamental features of malignancies. It is noteworthy that the inherent variations exist not only between patients with same type of malignancies (intertumor heterogeneity) but also within any individual tumor (intratumor heterogeneity)[7]. Intratumor heterogeneity implies the inherent temporal-spatial differences between distinctive subpopulations of tumor cells within the same tumor at both genetic and epigenetic levels[8]. In-depth sequencing technology enables the identification of different regions of a single tumor entity that harbor subclones with distinct genetic and epigenetic features[9]. Moreover, non-cancerous cells (for instance, stromal cells, infiltrating immune cells, extracellular matrix, vascular endothelia cells, etc.) interact with the surrounding cancerous subpopulations and form the regional microenvironments[10]. Consequently, tumoral and microenvironmental factors confer distinctive subpopulations of cancer cells with distinctive biological features and differential responses to chemotherapeutics. This adds to the complexity of cancer treatment and leads to lethal consequences, including tumor relapse and chemoresistance. Regarding gastric cancer, multiple studies have demonstrated its intratumor heterogeneity at molecular, histological, and phenotypic levels[7]. For instance, novel molecular-based classification launched by the Cancer Genome Atlas in 2014 and other genomic studies not only highlight the heterogeneity of GC but also imply its negative influence on tumor response to therapeutics agents targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), c-MYC, etc[11-13].

Two major models have been proposed to interpret intratumor heterogeneity. The clonal evolution (CE) model posits that somatic mutations stochastically occur on various clones within the tumor, leading to their differential growth patterns. Mutated clones with growth advantages will expand, whereas others with disadvantageous mutations will be outcompeted. As this scenario might be presented at different sites and different stages during cancer progression, the spatial-temporal tumor heterogeneity is consequently installed[14]. Alternatively, the cancer stem cell (CSC)/tumor-initiating cell (TIC) model was introduced based on the discovery that only a minor subpopulation of cancer cells generates tumor in vivo and maintains its self-renewal potential[15]. Both CSCs and TICs are widely used in the literature. However, the term of TIC highlights the capacity of these cells to (re)generate tumors during in vivo serial xenotransplantation, which is currently the gold standard for functionally validating and evaluating their tumorigenic capacity and self-renewal potential[16]. Indeed, key features of these distinctive subsets of cancer cells include: (1) Initiating and maintaining tumor growth; (2) preserving self-renewal potential; (3) giving rise to both tumorigenic and non-tumorigenic cancer cells; and (4) being highly resistant to chemotherapy[17]. Consequently, TICs establish intratumor heterogeneity by generating a cellular hierarchy, with very primitive TICs at the apex generating both daughter TICs and more differentiated non-TICs downwards. Recent genetic and functional studies not only identify somatic mutations within certain TIC clones but also demonstrate that these mutations influence their phenotypic features, generating distinctive TIC subclones[18]. As CE and TIC models are not mutually exclusive, these two models could be integrated. Remarkably, well-differentiated cells are shown to regain TIC properties through the process of dedifferentiation[19]. Collectively, these studies indicate that TICs are in dynamic status with substantial plasticity that is subjected to the regulation of multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors[20,21]. These findings contribute to a comprehensive interpretation of intratumor heterogeneity through evolving characterization of TICs.

GC is both genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous, which could be explained by gastric tumor-initiating cells (GATICs) that interact with genetic/epigenetic and microenvironmental factors[22,23]. Here we systemically review the GATICs from multiple perspectives including: (1) Identification and origination of GATICs; (2) plasticity of GATICs and their regulatory mechanisms; and (3) clinical implications of GATIC-targeted therapy.

Identification and validation of GATICs

Identification of GATICs is executed from three major aspects: Putative cell surface markers, efflux potential, and chemotherapeutics of GATICs[24]. Further functional validation of GATICs can be achieved with serial xenotransplantation of purified TIC subpopulation, which aims to evaluate its tumorigenicity and self-renewal capacity in vivo[25].

Identification of GATICs by cell surface markers

GATICs account for a minor subpopulation of GC cells that are endowed with significantly enhanced tumorigenic and self-renewal capacities. Key features of GATICs are partially similar with the characteristics of normal gastric stem cells (GSCs). Therefore, one major strategy of GATIC identification is through the detection of specific cell surface markers expressed on GSCs[26].

CD44 was the first putative cell surface marker identified for GATICs. As a universally recognized stem cell marker, this transmembrane glycoprotein mainly mediates cell-cell interaction, cell adhesion, and migration in healthy tissues[27]. Studies have shown that CD44(+) tumor cells regenerate heterogeneous tumors, demonstrate self-renewal capacity in vivo, and promote tumor progression, especially metastasis through oncogenic and stemness-related signaling pathways[28]. In 2009, Takaishi et al[29] demonstrated that fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)-sorted CD44(+) cells from three common GC cell lines exhibited enhanced TIC properties, including sphere formation in vitro and tumorigenicity in immune-deficient mice during serial transplantation, whereas CD44 knockdown induced compromised TIC properties both in vitro and in vivo. More specifically, CD44v8-10, a predominant CD44 variant, was identified as a specific GATIC marker, as exogenous overexpression of CD44v8-10, rather than standard CD44, improved the tumorigenicity in vivo[30]. Since combination of multiple cell surface markers improved the specificity of TIC identification, several studies have further demonstrated other putative GATIC subpopulations expressing both CD44 and other cell surface markers, including EpCam, CD24, etc[31,32]. Notably, CD44(+)CD54(+) circulating tumor cells captured from GC patients’ peripheral blood enabled sphere formation even at the single cell level. Moreover, the rapidly developed CD44(+)CD54(+) cell-derived tumors histologically resembled the matching primary tumor, indicating the improved specificity of GATIC population co-expressing multiple putative cell surface markers[33].

CD90 was recently identified as a GATIC specific cell surface marker. Indeed, it is recognized as a marker for a variety of normal and cancer stem cells[34]. Jiang et al[35] identified a GATIC population in primary gastric tumors characterized by its CD90 phenotypic features. CD90(+) cells were enriched in TIC-enriched cell culture condition, and these cells enabled tumor initiation with the minimum of 1 × 103 cells. Remarkably, the cellular hierarchy of GC could be restored by CD90(+) cells at a single cell level, strongly indicating their self-renewal capacity in GC. It was further shown that both tumorigenicity and tumor progression could be compromised by anti-ERBB2 therapeutic monoclonal antibody through inhibiting CD90(+) cell population in GC tumor mass[36].

Leucine rich repeat containing G-protein coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5) is a well-investigated stem cell marker across the gastrointestinal tract. Lgr5(+) stem cells were shown to drive self-renewal in the stomach and establish long-lived gastric units[37]. Thus, the role of Lgr5(+) cells during the initiation and progression of gastric malignancies has also been studied. Simon et al[38] reported that an elevated number of Lgr5(+) stem cells might be involved in gastric tumorigenesis. Moreover, Gong et al[39] showed that therapeutic antibodies targeting Lgr5(+) cells significantly inhibited tumor growth and prevented tumor recurrence, and Wang et al[40] demonstrated that GATIC-enriched tumor spheres highly expressed Lgr5(+).

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) is another universal marker for multiple cancers, including GC[41]. It is a family of enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of aromatic aldehydes to carboxyl acids. Multiple studies have shown that ALDH(+) GC cells not only contribute to the generation of heterogeneous tumor entity and the maintenance of GATIC features but also facilitate chemoresistance and tumor relapse[42,43]. An extensive study that profiled the expression of putative GATIC cell markers even claims that ALDH is one of the most specific biomarkers for GATICs in highly tumorigenic and chemoresistant non-cardia GC, regardless of histological type[44].

Furthermore, it has been accepted that combination of multiple TIC markers could potentially/possibly increase the specificity of identified TIC subpopulations. In GC, the most common pattern of combined GATIC marker expression is CD44 plus another identified marker. All the putative GATIC markers, including GATICs expressing single and multiple cell surface markers, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Putative cell surface markers of gastric tumor-initiating cell

| Putative marker | Tumor sphere formation (in vitro) | Tumor formation during serial engraftment (in vivo) | Limiting dilution assay | Chemo-resistance | Others | Ref. |

| CD44 | + | + | Not conducted | + | (1) Capacity of cell differentiation (2) Giving rise to both CD44+ and CD44- GC cells (3) Independent prognostic factor of GC patients | Takaishi et al[29] Yoon et al[119] |

| CD44/CD24 | + | + | + | Not conducted | Capacity of cell differentiation | Zhang et al[32] |

| CD44/CD54 | + | + | + | Not conducted | (1) Capacity of cell differentiation (2) Detectable from peripheral blood | Chen et al[33] |

| CD44/CD26 | + | + | Not conducted | + | / | Nishikawa et al[127] |

| CD44/EpCam | + | + | + | + | (1) Capacity of cell differentiation (2) Restoration of histological heterogeneity from single CD44/EpCam+ cell | Han et al[31] |

| CD44v810/EpCAM | + | + | + | + | CD44v8-10 but not CD44 standard increase the frequency of tumor initiation | Lau et al[30] |

| CD90 | + | + | + | + | Restoration of cellular hierarchy from single CD90+ cell | Jiang et al[35] |

| CD133 | + | + | Not conducted | + | Independent prognostic factor of GC patients | Zhang et al[128] |

| Lgr5 | + | + | Not conducted | Not conducted | / | Wang et al[40] |

| ALDH | + | + | + | + | / | Nishikawa et al[42] |

| ALDH1/REG4 | Katsuno et al[45] | |||||

| Oct4/Sox2/Nanog | + | + | Not conducted | + | Independent prognostic factor of GC patients | Liu et al[129] |

ALDH: Aldehyde dehydrogenase; GC: Gastric cancer.

Notably, several studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between reported GATIC markers and histological subtypes of GC. For instance, CD44 is more frequently and highly expressed in the intestinal subtype GC cells with moderate differentiation, whereas ALDH correlated with the diffuse subtype and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype[45,46]. Moreover, Lei et al[47] recently conducted novel classification of GC based on the analysis of gene expression patterns and claimed that the mesenchymal subtype had TIC properties such as high expression of putative GATIC markers, maintenance of an undifferentiated state, and enhanced activity of TIC-associated signaling pathways[48]. These studies further highlight tumor heterogeneity in terms of GATICs with specific markers differentially expressed by gastric malignancies.

Identification of GATICs by differential efflux potential

Although identification of TICs through putative cell surface markers has been extensively established, the specificity and accuracy of these markers are still under debate as the inconsistency of studies investigating the same markers has been observed[49]. An alternative to identify TICs is the differential efflux potential-based strategy. In principle, TICs highly express ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which facilitate the cells’ ability to export foreign bodies, such as therapeutic compounds, and thereby endow TICs with key features of reduced chemosensitivity and enhanced multidrug resistance. Consequently, after exposing a whole cancer cell population to Hoechst 33342, a classic cell dye, a differential amount of residual Hoechst 33342 within non-TICs and TICs could be observed. Most cancer cells with much retained Hoechst 33342 were from the main population (MP), whereas the minor subpopulation of TICs with significantly eliminated Hoechst 33342 were defined as the side population (SP). As FACS enables the discrimination between MP and SP, this strategy has been widely applied to identify the TIC population[50]. In GC, Fukuda et al[51] and She et al[52] respectively demonstrated that SP cells isolated from either GC cell lines or tumor samples exhibited improved sphere formation in vitro and tumorigenicity in vivo. Moreover, Tian et al[53] isolated SP cells from multiple GC cells lines and showed that SP cells not only conferred an asymmetric cell division pattern but also exhibited elevated resistance to cisplatin and adriamycin, both of which are key characteristics of GATICs. Although these studies imply that SP cells possibly possess an enriched population of GATICs, a recent study suggested that not all SP cells contain GATICs. In this study, SP cells from BCG823 cell line showed equal tumorigenicity as MP cells, indicating that SP alone may not be potent enough to distinguish GATICs from normal GC cells[54].

Purification of GATICs through chemotherapeutic reagents

Apart from the above-mentioned strategies, chemotherapeutics screening can also be applied to obtain TIC populations that are inherently resistant to drugs. In fact, Xue et al[55] reported a vincristine-preconditioning approach for GC cell line SGC7901 to obtain cells with increased GATIC markers, not only forming 3D structures resembling the differentiated gastric crypts but also displaying mesenchymal characteristics. A similar study conducted by Xu et al[56] showed that preconditioning treatment of 5-fluorouracil to SCG7901 and AGS cell lines enriched the population with up-regulated GATIC markers, enhanced tumorigenicity and self-renewal in vivo, and enhanced toleration to the insults from chemotherapy.

ORIGIN OF GATICS

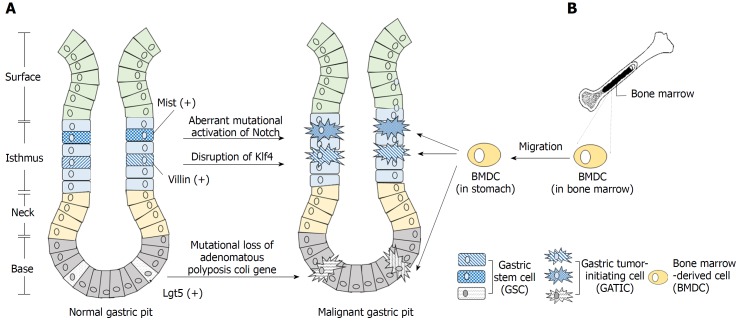

As GC itself is highly heterogeneous, its initiation is also a multi-stepwise process critically involving multiple factors. Genetic factors, infection of H. pylori, environmental elements, etc. contribute to the abnormal alteration of the gastric epithelium, especially metaplasia and dysplasia, which pave the basis for final development of gastric malignancies[57,58]. During this process, certain types of cells are abnormally transformed into GATICs, which install the cellular hierarchy with itself at the apex, giving rise to both self-renewal, tumorigenic GATICs and differentiated non-TICs. The major potential origins of GATICs are normal gastric stem cells and bone marrow-derived cells (Figure 1). Recent studies also preliminarily suggest that dedifferentiated gastric epithelial cells (GECs) could regain stemness features under certain circumstances, indicating its potential role as an origin of GATICs[59,60]. However, more rigorous and sufficient data are needed to support this proposal.

Figure 1.

Origination of gastric tumor-initiating cells. A: Evidence suggests that the gastric stem cell (GSC) is one major origin of the gastric tumor-initiating cell (GATIC). GSCs exist in the isthmus and bottom of the gastric pit. Certain genetic, epigenetic, and/or environmental factors potentially transform these GSCs into malignant GATICs. For instance, Mist(+) and Villin(+) GSCs in the isthmus and Lgr5(+) GSCs in the bottom could act as the origins of GATICs through multiple signaling pathways; B: GATICs are also presumed to originate partially from bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs). The recruitment of BMDCs to stomach by chemokines and other factors is in parallel with the multi-step progression of gastric cancer (GC), which lays the basis for the presumption that BMDCs undergo the malignant transformation into GATICs and promote GC development, the underlying mechanism of which requires further investigation.

GATICs derived from normal gastric stem cells

Gastric epithelial mucosa consists of four types of cells: chief cells, parietal cells, mucous cells, and enteroendocrine cells, all of which are derived from epithelial stem cells. These stem cells generate a cellular hierarchy of differentiation and proliferation and maintain the integrity of gastric mucosa[61]. Extensive studies of stem cells in the gastric epithelium identified a variety of GSCs with specific markers and restricted locations. For instance, Lgr5(+) cells at the bottom of adult pyloric glands[37], Sox2(+) cells located slightly above the bottom of pyloric and fundic glands, Villinβ-gal/(+) and Mist1(+) cells in the isthmus etc. are all GSCs with distinctive functions during normal development of the gastric mucosa[62,63].

It has long been postulated that resident tissue stem cells are the major resource of TICs, as malignancies could arise from the stem or progenitor cells in situ[26]. In 2008, McDonald et al[64] firstly proposed that the expansion and spread of mutated GSCs underlie the local progression of GC. Since then, multiple oncogenic mutations in GSCs have been identified. Adenoma is initiated when mutational loss of adenomatous polyposis coli gene induced by tamoxifen occurred in Lgr5(+) stem cells[37]. Under circumstance of chronic inflammation, aberrant activation of Notch and mutational alteration of E-cadherin in Mist(+) stem cells in the isthmus induced the development of intestinal and diffuse type of GC, respectively[63]. Moreover, mice with disrupted Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) in Villin(+) antral mucosa cells develop GC more frequently than mice with normal Klf4 function, indicating dysfunctional mutation of a tumor suppressor gene in GSCs can also induce gastric carcinogenesis[65]. Taken together, it is speculated that genetic alterations and mutations transform normal GSCs into oncogenic GATICs, which then initiate and promote tumor development. In other words, normal GSCs are a major putative origin of GATICs (Figure 1A).

GATICs derived from bone marrow-derived cells

Bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) are recognized as the most primitive uncommitted stem cells in adult since they potentially possess substantial plasticity as well as exhibit motility, migrating towards the sites of inflammation or injury[66]. The potential role of BMDCs as a source of malignant cells was not been identified until 2004 when Houghton et al[67] discovered that GC could originate from bone marrow-derived sources. In that study, Helicobacter C57BL/6 mouse model showed that H felis-caused chronic inflammation and induced initiation and development of GC. This process was strikingly paralleled with the recruitment of BMDCs followed by dramatic population of bone marrow-derived glands in the abnormal gastric epithelial[67]. Varon et al[68] further confirmed that the multi-step abnormal development of gastric epithelial induced by H. pylori was accompanied by significant accumulation of BMDCs. Notably, approximately 25% of the dysplasia lesions were bone-marrow derived. These discoveries strongly indicated that BMDCs, as a potential source of GATICs, could undergo abnormal transformation and contribute to GC progression, especially by migrating into the stem cell microenvironment of inflammatory tissues (Figure 1B)[69]. However, a recent study contradicted the claim and reported that BMDCs were only sporadically found in stroma and not the epithelium or glands of GC induced by carcinogens, including N-nitroso-N-methylurea and H. felis[70]. Therefore, more investigations are required to characterize further the process of aberrant transformation of BMDCs and to confirm them as a potential source of GATICs.

PLASTICITY OF GATICS AND ITS REGULATORY MECHANISMS

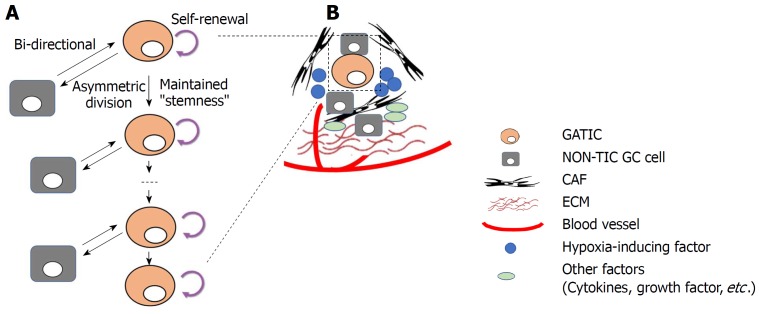

Plasticity of GATICs

As briefly mentioned above, both the CE model and TIC model are major proposals for the interpretation of intratumor heterogeneity. The CE model highlights the stochastic genetic/epigenetic alterations that occur in cancer cells at various sites and phases during cancer progression, resulting in the formation and expansion/extinction of different subpopulations of cancer cells with their own phenotypes[71]. In contrast, the TIC model stresses the essential role of highly tumorigenic and self-renewal TICs to generate daughter TICs with similar characteristics (symmetric division) and non-TICs with limited potential of self-renewal, tumorigenicity, and metastasis (asymmetric division)[72]. The co-existence of TICs and non-TICs with distinctive biological properties reflects the intratumor heterogeneity. Furthermore, it was repeatedly discovered that differentiated cancer cells could regain “stemness” under the regulation of multiple factors, demonstrating the existence of bidirectional conversion between TICs and non-TICs[73]. In light of this dynamic transition, TICs are more recognized as a phenotypic status or mode rather than a fixed subset of cancer cells, indicating that the plasticity of TICs plays an essential role in the intratumor heterogeneity[74]. Therefore, a unified model of CE and TICs was recently proposed to stress the plasticity of TICs: Primitive TICs with substantial capacity of tumorigenicity and self-renewal develop the cellular hierarchy. Meanwhile, they generate multiple subclones that subsequently acquire distinctive genetic mutations and/or epigenetics. Some subclones retain TIC features and continue to expand, whereas other subclones are in the non-TIC status. Nevertheless, a proportion of non-TIC subclones could reversely acquire TIC features under the regulation of genetic/epigenetic factors and/or tumor microenvironment (TME)[18].

In GC, GATIC plasticity could also be identified. Bessède et al[75] demonstrated that deletion of IQGAP1, a scaffold protein modulating cell plasticity and actin cytoskeleton, in the MKN74 GC cell line induced enhanced tumor sphere formation and increased expression of GATIC markers, both of which are major GATIC features in vitro. In vivo experiments further showed that H. pylori-induced gastric dysplasia was further enhanced by IQGAP1 deletion. Similarly, Yong et al[76] reported that CagA-positive H. pylori induced the transformation of MKN45 and AGS GC cell lines into TIC-like cells as they manifested corresponding properties in vitro. A mechanism investigation showed that CagA upregulated Nanog and Oct4 via the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which underlies the process of TIC status transition. Moreover, multiple studies have shown that the dedifferentiation of mature gastric epithelial cells can reacquire stemness features, including tumor-initiation, expression of TIC markers, etc[60,77,78]. All these studies highlight TIC plasticity and demonstrate a dynamic conversion of cells with and without TIC properties when a variety of factors are involved in the process of regulation (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Plasticity of gastric tumor-initiating cells. A: Gastric tumor-initiating cells (GATICs) give rise to both daughter GATICs and non-TIC gastric cancer (GC) cells (asymmetric division) while maintain their self-renewal capacity and “stemness”. Notably, recent studies demonstrate that differentiated non-TIC GC cells could undergo dedifferentiation and re-acquire the properties (or status) of GATICs. Thus, the bi-directional transition between TIC and non-TIC indicates the plasticity of GATICs, which is regulated by both genetic/epigenetic alterations and tumor microenvironmental factors; B: GATICs reside in the tumor-microenvironment, which consists of cancer cells (GATICs and non-TIC GC cells) as well as non-cancerous cells, such as cancer-associated fibroblast, extracellular matrix, blood supply, hypoxia (hypoxia-inducing factor), and other secreted factors, such as cytokines, growth factors. GATICs interact with these factors within the TIC niche, which exerts regulatory influence on the plasticity of GATICs through various signaling pathways.

Regulatory mechanisms of GATICs and their plasticity

Both intrinsic factors (genetic and epigenetic alterations) and extrinsic factors (mainly tumor microenvironment) have been implicated in the regulation of GATICs and their plasticity (Figure 2).

Genetic and epigenetic alterations: Aberrantly dysregulated key effectors in several signaling pathways modulate gastric tumorigenesis and essential GATIC properties. Studies have shown that the activated hedgehog (HH) pathway significantly contributed to GC cell proliferation[79]. It was further demonstrated that sonic hedgehog (SHH) pathways are essential for maintaining the status of GATICs: Ptch and Gli1. Two SHH pathway key effectors were significantly overexpressed in GATIC-enriched sphere cultures. Significantly blocking this pathway not only decreased the expression of putative GATIC markers, including CD44 and CD24, but also reduced the self-renewal and tumorigenic capacity of GATICs, which are enriched in sphere cultures[80]. Nanog, a key transcription factor, not only maintained the self-renewal and pluripotency in embryonic stem cells but also contributed to the progression of multiple malignancies[81]. In GC, Nanog is aberrantly overexpressed in cancerous tissues. More importantly, it maintains the TIC features primarily through its interaction with multiple factors, especially the HH pathway and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), which is another well-investigated regulating factor of GATICs[82]. Activated STAT3 has been observed in many types of cancers and is critically involved in cancer progression[83]. Jiang et al[84] recently reported that interleukin (IL)-17 promoted the invasive transformation of quiescent GATICs through facilitating phosphorylation and subsequent activation of STAT3. Exposure of quiescent GATICs to an optimal duration and concentration of IL-17 led to an increase in N-cadherin and vimentin, which are epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT)-related makers, as well as in the invasive and clonal proliferative abilities of GATICs[84]. Notably, epithelial cells that undergo the process of EMT acquire TIC phenotypes. Another EMT-contributing signaling pathway is the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which reportedly maintains the self-renewal, tumorigenesis, and chemoresistance of TICs[85]. Oshima et al[86] reported that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway maintained the undifferentiated status of gastric progenitor cells, and co-activation of both Wnt and prostaglandin E2 induced sequential metaplasia, dysplasia, and malignant transformation of the gastric epithelium. Other studies have shown that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway induced the acquirement and maintenance of TIC features in GC[87]. Investigations of other major stemness-associated factors, including TGFβ, Notch1 etc., and their related signaling pathways hint their potential involvement in the maintenance of defined characteristics of TICs in certain types of cancers. However, more studies are required to validate their relationships with GATICs[88-90].

Similarly, epigenetic alterations also critically regulate TICs and their plasticity. The malignant transformation of somatic cells, maintenance of TIC self-renewal capacity, and bidirectional transition between TICs and non-TICs are all under the regulatory influence of epigenetic factors[91]. Major epigenetic variations, including DNA hypermethylation, histone modification, and silencing of both microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), have been shown to regulate GATICs. Activated oncogene ERas not only drives the tumorigenic growth but is also involved in maintaining the TIC properties in GC[92,93]. Yashiro et al[93] discovered that ERas promoter methylation was found in six of seven GC cell lines without ERas expression, which could be reversed by DNA methyltransferase inhibitor. Loss of methylation in the promoter of ERas induced ERas activation and further increased SP cells in which GATICs were enriched. Tomita et al[94] reported that methylation and histone modification at the Tff1 promoter led to the extensive inactivation of the tumor suppressor gene Tff1 and further facilitated the initiation of GC in MNU-treated wild-type mice. The epigenetic silencing in the TFF1 promoter could be partially reversed by gastrin, indicating the role of epigenetic silencing in the plasticity of GC development. Moreover, epigenetic alterations could indirectly regulate the status of GATICs through influencing key regulators in TIC-related signaling pathways. Yoda et al[95] reported that aberrant methylation of DKK3, NKD1, and SFRP1, negative regulators of the WNT pathway, induced the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and further contributed to regulation of multiple aspects of GATIC functional activities. Wang et al[96] reported that hypomethylation of the SHH promoter increased the aberrant expression of SHH ligands in GC cells, leading to further enhanced SHH pathway activity and dysregulated GATIC properties. Non-coding RNA can also exert regulatory effects on GATICs in a similar manner. For instance, microRNA-106b down-regulated Smad7 and subsequently activated the TGF-β/Smad pathway, which in turn promoted the self-renewal and EMT characteristics of CD44(+) GC cells[97]. MicroRNA4835p was found to be overexpressed in GC spheroid cultures. Furthermore, this microRNA increased the expression of βcatenin and its downstream molecules, including cyclin D1, Bcl-2, and MMP2, which enhanced both invasiveness and self-renewal capacity of GC cells[98].

Tumor microenvironments (TIC niches): Apart from intrinsic regulation of GATICs and their plasticity by genetic and epigenetic alterations, TIC niches are also key GATIC regulators within the tumor microenvironment (TME) (Figure 2B)[99]. In principal, TME is composed of fibroblastic stromal cells, endothelial and perivascular cells, immune cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), and networks of cytokines and growth factors, all of which play extensive roles in regulating GATICs[100]. It was reported that cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) significantly increased the proportion of a side population (SP) of GC cells, with characteristics of cell stemness and the expression levels of GATICs markers in scirrhous gastric cancer cell lines. Mechanism investigation showed that this process was significantly influenced by the activity of TGF-β[88]. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts (BMFs) are also major components of GATIC niches. The expansion and relocation of BMFs create a mesenchymal stem cell niche to facilitate tumor progression[101]. BMF-conditioned medium induced the formation of GC spheres expressing stem cell signatures and exhibiting features of self-renewal, and EMT transition through TGF-β and Cxcr4/Cxcl12-dependent pathways[102]. Another fundamental characteristic of TIC niches is hypoxia. As tumor microenvironment is usually hypoxic, TICs are constantly under the pressure from hypoxia through the mediation of hypoxia-induced transcription factor 1α and 2α (HIF-1/2α)[103]. In GC, it was shown that HIF-1α induced EMT in GATIC-enriched spheroid cultures through the Snail signaling pathway[104]. Another study demonstrated that HIF-1α down-regulated the expression of CD133, a putative GATIC marker, in GC cell lines, suggesting that mTOR signaling is involved in the process[105]. Other major components in TIC niches, including tumor-associated macrophages, blood vessels, and soluble cytokines and growth factors, have been proven to regulate TIC activities and plasticity in multiples types of cancers. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that GITC niche components exert extensive regulatory influences on GATICs and its plasticity.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF TARGETING GATICS

Chemotherapy plays an essential role in the comprehensive treatment of GC. Unfortunately, development of tumor resistance to conventional chemotherapeutic agents poses a major obstacle in the eradication of GC. Intratumor heterogeneity of GC essentially underlies the chemoresistance. The bulk of proliferating progenitor cells or differentiated tumor cells could be effectively targeted by anti-cancer drugs, whereas a minor proportion of GATICs remain unaffected by cytotoxic agents[106]. GATICs survive from chemotherapy and re-generate heterogeneous subpopulations of GC cells, giving rise to tumor recurrence and leading to poor prognosis of GC patients.

Mechanisms of GATIC chemoresistance

GATICs evade and/or tolerate the insults from chemotherapy through multiple routes. Firstly, GATICs highly express ABC transporters that function as efflux pumps of incoming reagents[107]. Consequently, GATICs constantly pump out anticancer drugs and avoid their cytotoxic effects[108]. Secondly, ALDH(+) GC cells are recognized as GATICs due to their substantially enhanced tumorigenicity and self-renewal capacity[109]. It was found that the expression of Notch1 and Shh was increased in this highly chemoresistant subpopulation, indicating that Notch1 and Shh signaling underlies the chemoresistance of GATICs[110]. Another well-recognized GATIC cell marker is CD44, which also confers GATICs with the capacity of drug resistance[111]. Chemoresistant GATICs are marked by increased glycolytic flux with activated pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)[112]. Tamada et al[111] demonstrated that CD44 enhanced the glycolytic phenotype of GATICs by interacting with the pyruvate kinase M2, whereas CD44 ablation inhibited both glycolytic flux and PPP but increased intracellular level of reactive oxygen species, which are harmful to cancer cells, leading to enhanced effects of chemotherapy in hypoxia GC cells. All these mechanisms suggest that CD44 contributes to chemoresistance of GC cells through metabolic modulation. Other studies claim that stemness-related signaling pathways, including the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway, also contribute to chemoresistance through their interaction with CD133 and ABCG2, respectively[110]. Moreover, the cancer cell-stroma interface of the TIC niches within tumor microenvironment hinders the drug entrance, and thereby reduces the efficiency of chemotherapy[113]. These findings facilitate the design of therapeutic agents that specifically target GATICs and thereby improve the drug efficiency.

GATIC-Targeted therapies

Based on the uncovered mechanisms of chemoresistance, two major strategies for elimination of the GATIC population have been developed: differentiation therapy and elimination therapy[114]. The former one implies treatment that induces GATIC differentiation to suppress their self-renewal capacity, and thereby making GC progression unsustainable in the long run. Han et al[115] reported that ATOH1, a helix-loop-helix transcription factor, was induced during GATIC differentiation. They demonstrated that overexpression of ATOH1 in GATICs induced their differentiation and reduced their tumorigenicity both in vitro and in vivo, suggesting ATOH1 as a potential target for differentiation therapy targeting GATICs[115]. Similarly, lentiviral vector-based knockdown of PGK1, a metabolic enzyme that is involved in the dissemination of GC cells, induced the differentiation of the CD44(+) GATIC population and significantly inhibited both tumor growth and metastasis in immunodeficient mice[116]. These studies imply the feasibility of differentiation therapy to overcome chemoresistance of GC, although no therapeutic agent has yet been developed or entered clinical trials.

The other strategy to eliminate directly GATICs mainly focuses on self-renewal signaling pathways that are aberrantly overexpressed in GATICs. For instance, the SHH signaling pathway is abnormally dysregulated in GATICs. Ptch and Gli1 are two key SHH pathway genes targeted by cyclopamine[117]. Song et al[80] reported that treatment of cyclopamine not only caused an enhanced reduction in self-renewal capacity but also improved the efficacy of oxaliplatin on GATIC-enriched tumor sphere cells. Vismodegib is another SHH pathway inhibitor that directly binds to SMO and subsequently inhibits the activation of downstream GLI family of transcription factors and their regulation on target genes[118]. A biomarker-based analysis of a phase 2 clinical trial of Vismodegib combined with FOLFOX vs FOLFOX demonstrated that Vismodegib could potentially reverse chemotherapy resistance in the population of patients with high CD44-expressing GC tumors[119]. Another featured pathway in GATICs is the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is essentially involved in maintenance of TIC properties and induction of EMT. Gupta et al[120] conducted a high-throughput screening to identify selective TIC inhibitors and discovered that salinomycin, a specific suppressor of Wnt/β-catenin pathway, potently inhibited TICs in multiple cancer types. Zhi et al[121] subsequently observed that chemoresistant GATICs highly expressing ALDH were relatively sensitive to salinomycin when compared to ALDH-low GC cells, indicating salinomycin as a selective therapy for GATIC fraction. Similarly, Liu et al[122] reported that ICG-001, a small molecule disrupting the co-activator of Wnt/β-catenin-mediated transcription, significantly suppressed GC cell growth, reduced their stemness properties, and enhanced their chemosensitivity to 5-Fu and cisplatin. Napabucasin is an orally administered small molecule that inhibits STAT3, β-catenin, and NANOG. Several studies have demonstrated its potent anti-stemness effect in various types of cancers[121]. A phase Ib/II clinical trial of Napabucasin combined with paclitaxel in advanced gastric and gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma not only demonstrated its safety but also observed its anti-cancer activity, leading to an on-going phase III study of Napabucasin in combination with weekly paclitaxel as the second-line treatment for gastric/GEJ cancer[123]. Moreover, since overexpression of ABC transporters in GATICs leads to substantial efflux of therapeutic agents and chemoresistance, it is postulated that selectively inhibiting ABC transporters may be an alternative strategy to tackle chemoresistance. Indeed, multiple ABC transporter inhibitors (especially targeting ABCG2) have been recently developed to sensitize multidrug resistant (MDR) cancer cells[124,125]. Although some promising effects of improving chemosensitivity have been observed, significant side effects, such as cytotoxic effects on normal stem cells and blood-brain barrier, imply that substantial caution should be applied to obtain optimal outcomes[126]. So far, there are multiple developed therapeutic strategies targeting GATICs, either in the preclinical phase of experimental investigation or being tested in the clinical trials as developed chemotherapeutic agents. The most representative examples are shown in Table 2[127-137].

Table 2.

Gastric tumor-initiating cell-targeted therapeutic strategies/agents

| Therapeutic target | Therapeutic agent | Investigation status | Underlying mechanism | Treatment | Result of treatment | Ref. |

| ATOH1 | Lentiviral vector-based | Preclinical investigation | Overexpression of ATOH1 mediates its transcriptional activity to downstream genes and induces the differentiation of GATICs | Lentiviral vector-based overexpression of ATOH1 | (1) Induction of CD44+/Lgr5+ GATICs differentiation (2) Reduced tumorigenicity of GATICs both in vitro and in vivo | Han et al[115] |

| PGK1 | Lentiviral vector-based | Preclinical investigation | Knockdown of PGK1 alters the glycolytic metabolism of GATICs not only induces GATIC differentiation but also improve their chemosensitivity | Lentiviral vector-based knockdown of PGK1 | (1) Induction of CD44+ GATICs differentiation (2) Inhibited tumor growth and metastasis in vivo | Zieker et al[116] |

| CD44v | Sulfasalazine | Phase I dose-escalation clinical study in EPOC1205 | Targeting CD44v by inhibiting xCT which mainly interacts with CD44v and maintains high level of GSH | 12 g/d, 4x/d with 2 wk as one cycle, oral administration | Reduced level of CD44v positive GATICs in some patients | Shitara et al[130] |

| EpCam | Catumaxomab | Phase II/III clinical trial of advanced gastric carcinoma_NCT00836654 | Direct targeting CD3 and EpCam | Paracentesis +/- Catumaxomab | Clinical benefit (prolonged PFS and less symptoms of ascites) in GC patients with secondary malignant ascites | Heiss et al[131] |

| EpCam | Catumaxomab | Phase II clinical trial of advanced gastric carcinoma_NCT01784900 | Direct targeting CD3 and EpCam | Surgical resection followed by Catumaxomab | Intra-/postoperative administration of catumaxomab within multimodal treatment is feasible and tolerable | Goéré et al[132] |

| c-MET | Rilotumumab | Phase III clinical trial of locally advanced or metastatic gastric and GEJ carcinoma_NCT01697072 | Competitively targeting hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), ligand of c-MET receptor | ECX +/- Rilotumumab | Stopped early due to increased death risk | Doshi et al[133] |

| c-MET | Onartuzumab | Phase III clinical trial of metastatic HER2(-) and c-MET(+) Gastroesophageal Cancer_NCT01662869 | Direct targeting c-MET as a MET antagonist | FOLFOX6 +/- Rilotumumab | Insignificant prolong of PFS (6.9 mo vs 5.7 mo) and OS (11.0 mo vs 9.7 mo) | Shah et al[134] |

| c-MET | Tivantinib | Phase I/II clinical trial of advanced and metastatic adenocarcinoma of distal esophagus, GEJ and stomach_NCT01611857 | Inhibition of c-Met receptor tyrosine kinase | FOLFOX6 combined with Tivantinib | PFS: 6.1 mo and OS: 9.6 mo | Pant et al[135] |

| SHH signaling pathway | Cyclopamine | Preclinical investigation | Targeting overexpressed Ptch/Gli1 (key effectors in SHH pathway) | Direct addition of cyclopamine (5 μmol/L in vitro and 10 μmol/L in vivo) | (1) Reduced self-renewing capacity of GATIC-enriched tumor sphere (2) Enhanced efficacy of Oxaliplatin/Mitomycin inhibiting proliferation of tumor sphere | Song et al[80] |

| SHH signaling pathway | Vismodegib | Phase II clinical trial of advanced gastric and GEJ carcinoma_NCT00982592 | Targeting Smoothened (SMO) and its downstream GLI family members | FOLFOX +/- Vismodegib | (1) No significant improvement of anti-tumor activity (2) Potentially reverse the chemotherapy resistance of patients with high CD44-expressing tumor cells | Cohen et al[136] |

| Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | Salinomycin | Preclinical investigation | Blocking and degrading LRP6 (Wnt co-receptor) | Direct addition of Salinomycin (ranging from 1 μmol/L to 100 μmol/L in vitro) | Effectively kill ALDH-high GATICs which are resistant to 5-FU and CDDP | Mao et al[87] |

| Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway | ICG-001 | Preclinical investigation | Inhibiting CBP (co-activator of Wnt/β-catenin pathway) | Direct addition of ICG-001 (50 mg/kg/d, in vivo) | (1) Suppressed GC cell growth and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo (2) Reduced self-renewal capacity and enhanced efficacy of 5-Fu/cisplatin | Liu et al[122] |

| STAT3 signaling pathway | Napabucasin | Phase Ib/II dose-escalation and extension study of advanced gastric and GEJ carcinoma_NCT01325441 | Direct targeting Stat3, β-catenin and NANOG | Paclitaxel +/- Napabucasin | (1) Well-tolerated by GC patients even receiving high doses of chemotherapy (2) Observed anti-tumor activity but still needs to be further confirmed in the on-going BRIGHTER phase III clinical trial | Shah et al[137] |

GATIC: Gastric tumor-initiating cell; SHH: Sonic hedgehog; GEJ: Gastroesophageal junction; GC: Gastric cancer; ALDH: Aldehyde dehydrogenase.

CONCLUSION

The complexity of GC remains largely unsolved due to its heterogeneity, especially intratumor heterogeneity. TIC model is proposed to interpret the heterogeneity of GC. Accumulating TIC investigations demonstrate that GATICs contribute to intratumor heterogeneity under the influence of genetic/epigenetic and microenvironmental factors. Recent studies show the bidirectional conversion between TIC and non-TIC status, indicating the plasticity of GATICs. Although the underlying mechanisms of this scenario have been studied to some extent, it remains unclear how GATICs are regulated and influenced by intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Technological advances in genomic, especially sequencing technique at the single cell level, could trace the developing route of individual GC cells and potentially better model the intertwined relationships between GATICs and their regulatory factors. With respect to the GATIC-target therapy, several in vitro and/or in vivo functional experiments have demonstrated that targeting GATICs reduced chemoresistance and thereby improved the outcomes of drug treatment. However, the disparity of drug effects between preclinical studies and clinical trials has also been repeatedly observed. One major explanation is that current in vitro and in vivo models failed to recapitulate the real TME that plays crucial roles in regulating GATIC phenotypes and plasticity. With the application of Matrigel® and other specific cell culture materials, three-dimensional spheroid and even organoid cultures of GC have been recently generated to enrich TIC subpopulation and mimic the real status of GC cells within the microenvironment. As stroma and ECM, key aspects of TME, are still missing in current cultivation system, new methods, such as co-culture of patient-derived cancer cells and stromal cells within the ECM-like “scaffolds”, will be developed in the near future to represent better the tumor heterogeneity.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: March 21, 2018

First decision: April 24, 2018

Article in press: May 26, 2018

P- Reviewer: Chueh PJ, Kim SY S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Yin SY

Contributor Information

Jian-Peng Gao, Department of Surgery, Shanghai Institute of Digestive Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200025, China.

Wei Xu, Department of Surgery, Shanghai Institute of Digestive Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200025, China.

Wen-Tao Liu, Department of Surgery, Shanghai Institute of Digestive Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200025, China. wt_mygod@163.com.

Min Yan, Department of Surgery, Shanghai Institute of Digestive Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200025, China.

Zheng-Gang Zhu, Department of Surgery, Shanghai Institute of Digestive Surgery, Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200025, China.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saikawa Y, Fukuda K, Takahashi T, Nakamura R, Takeuchi H, Kitagawa Y. Gastric carcinogenesis and the cancer stem cell hypothesis. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:11–24. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marin JJ, Al-Abdulla R, Lozano E, Briz O, Bujanda L, Banales JM, Macias RI. Mechanisms of Resistance to Chemotherapy in Gastric Cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2016;16:318–334. doi: 10.2174/1871520615666150803125121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D, Deist T, Hinke A, Breithaupt K, Dogan Y, Gebauer B, Schumacher G, Reichardt P. Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer--a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO) Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2306–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim DH, Park KW, Oh SY, Kwon HC, Hwang IG, Lee SC, Nam E, Shin DB, et al. Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1513–1518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGranahan N, Swanton C. Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell. 2017;168:613–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gullo I, Carneiro F, Oliveira C, Almeida GM. Heterogeneity in Gastric Cancer: From Pure Morphology to Molecular Classifications. Pathobiology. 2018;85:50–63. doi: 10.1159/000473881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welch DR. Tumor Heterogeneity--A ‘Contemporary Concept’ Founded on Historical Insights and Predictions. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M, Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N, Stewart A, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:883–892. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Junttila MR, de Sauvage FJ. Influence of tumour micro-environment heterogeneity on therapeutic response. Nature. 2013;501:346–354. doi: 10.1038/nature12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alsina M, Gullo I, Carneiro F. Intratumoral heterogeneity in gastric cancer: a new challenge to face. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:912–913. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Böger C, Krüger S, Behrens HM, Bock S, Haag J, Kalthoff H, Röcken C. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric cancer reveals intratumoral heterogeneity of PIK3CA mutations. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1005–1014. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson AR, Weaver AM, Cummings PT, Quaranta V. Tumor morphology and phenotypic evolution driven by selective pressure from the microenvironment. Cell. 2006;127:905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baccelli I, Trumpp A. The evolving concept of cancer and metastasis stem cells. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:281–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201202014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishizawa K, Rasheed ZA, Karisch R, Wang Q, Kowalski J, Susky E, Pereira K, Karamboulas C, Moghal N, Rajeshkumar NV, et al. Tumor-initiating cells are rare in many human tumors. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fulawka L, Donizy P, Halon A. Cancer stem cells--the current status of an old concept: literature review and clinical approaches. Biol Res. 2014;47:66. doi: 10.1186/0717-6287-47-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medema JP. Cancer stem cells: the challenges ahead. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:338–344. doi: 10.1038/ncb2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shackleton M, Quintana E, Fearon ER, Morrison SJ. Heterogeneity in cancer: cancer stem cells versus clonal evolution. Cell. 2009;138:822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prasetyanti PR, Medema JP. Intra-tumor heterogeneity from a cancer stem cell perspective. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:41. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0600-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tatematsu M, Tsukamoto T, Inada K. Stem cells and gastric cancer: role of gastric and intestinal mixed intestinal metaplasia. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:135–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li K, Dan Z, Nie YQ. Gastric cancer stem cells in gastric carcinogenesis, progression, prevention and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5420–5426. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i18.5420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bekaii-Saab T, El-Rayes B. Identifying and targeting cancer stem cells in the treatment of gastric cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:1303–1312. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rycaj K, Tang DG. Cell-of-Origin of Cancer versus Cancer Stem Cells: Assays and Interpretations. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4003–4011. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takaishi S, Okumura T, Wang TC. Gastric cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2876–2882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams K, Motiani K, Giridhar PV, Kasper S. CD44 integrates signaling in normal stem cell, cancer stem cell and (pre)metastatic niches. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013;238:324–338. doi: 10.1177/1535370213480714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naor D, Nedvetzki S, Golan I, Melnik L, Faitelson Y. CD44 in cancer. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2002;39:527–579. doi: 10.1080/10408360290795574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takaishi S, Okumura T, Tu S, Wang SS, Shibata W, Vigneshwaran R, Gordon SA, Shimada Y, Wang TC. Identification of gastric cancer stem cells using the cell surface marker CD44. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1006–1020. doi: 10.1002/stem.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lau WM, Teng E, Chong HS, Lopez KA, Tay AY, Salto-Tellez M, Shabbir A, So JB, Chan SL. CD44v8-10 is a cancer-specific marker for gastric cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2630–2641. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han ME, Jeon TY, Hwang SH, Lee YS, Kim HJ, Shim HE, Yoon S, Baek SY, Kim BS, Kang CD, et al. Cancer spheres from gastric cancer patients provide an ideal model system for cancer stem cell research. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3589–3605. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0672-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C, Li C, He F, Cai Y, Yang H. Identification of CD44+CD24+ gastric cancer stem cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1679–1686. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1038-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen T, Yang K, Yu J, Meng W, Yuan D, Bi F, Liu F, Liu J, Dai B, Chen X, et al. Identification and expansion of cancer stem cells in tumor tissues and peripheral blood derived from gastric adenocarcinoma patients. Cell Res. 2012;22:248–258. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaikh MV, Kala M, Nivsarkar M. CD90 a potential cancer stem cell marker and a therapeutic target. Cancer Biomark. 2016;16:301–307. doi: 10.3233/CBM-160590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang J, Zhang Y, Chuai S, Wang Z, Zheng D, Xu F, Zhang Y, Li C, Liang Y, Chen Z. Trastuzumab (herceptin) targets gastric cancer stem cells characterized by CD90 phenotype. Oncogene. 2012;31:671–682. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh SR. Gastric cancer stem cells: a novel therapeutic target. Cancer Lett. 2013;338:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P, van de Wetering M, Snippert HJ, van Es JH, Sato T, Stange DE, Begthel H, van den Born M, et al. Lgr5(+ve) stem cells drive self-renewal in the stomach and build long-lived gastric units in vitro. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon E, Petke D, Böger C, Behrens HM, Warneke V, Ebert M, Röcken C. The spatial distribution of LGR5+ cells correlates with gastric cancer progression. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35486. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong X, Azhdarinia A, Ghosh SC, Xiong W, An Z, Liu Q, Carmon KS. LGR5-Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugate Eradicates Gastrointestinal Tumors and Prevents Recurrence. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1580–1590. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Z, Liu C. Lgr5-Positive Cells are Cancer-Stem-Cell-Like Cells in Gastric Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:2447–2455. doi: 10.1159/000430205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clark DW, Palle K. Aldehyde dehydrogenases in cancer stem cells: potential as therapeutic targets. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4:518. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.11.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishikawa S, Konno M, Hamabe A, Hasegawa S, Kano Y, Ohta K, Fukusumi T, Sakai D, Kudo T, Haraguchi N, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase high gastric cancer stem cells are resistant to chemotherapy. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:1437–1442. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Senel F, Kökenek Unal TD, Karaman H, Inanç M, Aytekin A. Prognostic Value of Cancer Stem Cell Markers CD44 and ALDH1/2 in Gastric Cancer Cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:2527–2531. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.9.2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nguyen PH, Giraud J, Chambonnier L, Dubus P, Wittkop L, Belleannée G, Collet D, Soubeyran I, Evrard S, Rousseau B, et al. Characterization of Biomarkers of Tumorigenic and Chemoresistant Cancer Stem Cells in Human Gastric Carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1586–1597. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katsuno Y, Ehata S, Yashiro M, Yanagihara K, Hirakawa K, Miyazono K. Coordinated expression of REG4 and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 regulating tumourigenic capacity of diffuse-type gastric carcinoma-initiating cells is inhibited by TGF-β. J Pathol. 2012;228:391–404. doi: 10.1002/path.4020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nosrati A, Naghshvar F, Khanari S. Cancer Stem Cell Markers CD44, CD133 in Primary Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2014;3:279–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lei Z, Tan IB, Das K, Deng N, Zouridis H, Pattison S, Chua C, Feng Z, Guan YK, Ooi CH, et al. Identification of molecular subtypes of gastric cancer with different responses to PI3-kinase inhibitors and 5-fluorouracil. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:554–565. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turner ES, Turner JR. Expanding the Lauren classification: a new gastric cancer subtype? Gastroenterology. 2013;145:505–508. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller TJ, McCoy MJ, Hemmings C, Bulsara MK, Iacopetta B, Platell CF. Objective analysis of cancer stem cell marker expression using immunohistochemistry. Pathology. 2017;49:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2016.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morii E. Heterogeneity of tumor cells in terms of cancer-initiating cells. J Toxicol Pathol. 2017;30:1–6. doi: 10.1293/tox.2016-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukuda K, Saikawa Y, Ohashi M, Kumagai K, Kitajima M, Okano H, Matsuzaki Y, Kitagawa Y. Tumor initiating potential of side population cells in human gastric cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1201–1207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.She JJ, Zhang PG, Wang X, Che XM, Wang ZM. Side population cells isolated from KATO III human gastric cancer cell line have cancer stem cell-like characteristics. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4610–4617. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i33.4610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian T, Zhang Y, Wang S, Zhou J, Xu S. Sox2 enhances the tumorigenicity and chemoresistance of cancer stem-like cells derived from gastric cancer. J Biomed Res. 2012;26:336–345. doi: 10.7555/JBR.26.20120045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang H, Xi H, Cai A, Xia Q, Wang XX, Lu C, Zhang Y, Song Z, Wang H, Li Q, et al. Not all side population cells contain cancer stem-like cells in human gastric cancer cell lines. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:132–139. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xue Z, Yan H, Li J, Liang S, Cai X, Chen X, Wu Q, Gao L, Wu K, Nie Y, et al. Identification of cancer stem cells in vincristine preconditioned SGC7901 gastric cancer cell line. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:302–312. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu ZY, Tang JN, Xie HX, Du YA, Huang L, Yu PF, Cheng XD. 5-Fluorouracil chemotherapy of gastric cancer generates residual cells with properties of cancer stem cells. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11:284–294. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.10248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Massarrat S, Stolte M. Development of gastric cancer and its prevention. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17:514–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zavros Y. Initiation and Maintenance of Gastric Cancer: A Focus on CD44 Variant Isoforms and Cancer Stem Cells. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;4:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aoi T, Yae K, Nakagawa M, Ichisaka T, Okita K, Takahashi K, Chiba T, Yamanaka S. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells. Science. 2008;321:699–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1154884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi YJ, Kim N, Chang H, Lee HS, Park SM, Park JH, Shin CM, Kim JM, Kim JS, Lee DH, et al. Helicobacter pylori-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition, a potential role of gastric cancer initiation and an emergence of stem cells. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:553–563. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wright NA. Epithelial stem cell repertoire in the gut: clues to the origin of cell lineages, proliferative units and cancer. Int J Exp Pathol. 2000;81:117–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2000.00146.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Qiao XT, Ziel JW, McKimpson W, Madison BB, Todisco A, Merchant JL, Samuelson LC, Gumucio DL. Prospective identification of a multilineage progenitor in murine stomach epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1989–1998. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayakawa Y, Ariyama H, Stancikova J, Sakitani K, Asfaha S, Renz BW, Dubeykovskaya ZA, Shibata W, Wang H, Westphalen CB, et al. Mist1 Expressing Gastric Stem Cells Maintain the Normal and Neoplastic Gastric Epithelium and Are Supported by a Perivascular Stem Cell Niche. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:800–814. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McDonald SA, Greaves LC, Gutierrez-Gonzalez L, Rodriguez-Justo M, Deheragoda M, Leedham SJ, Taylor RW, Lee CY, Preston SL, Lovell M, et al. Mechanisms of field cancerization in the human stomach: the expansion and spread of mutated gastric stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:500–510. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Q, Jia Z, Wang L, Kong X, Li Q, Guo K, Tan D, Le X, Wei D, Huang S, et al. Disruption of Klf4 in villin-positive gastric progenitor cells promotes formation and progression of tumors of the antrum in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:531–542. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Houghton J, Stoicov C, Nomura S, Rogers AB, Carlson J, Li H, Cai X, Fox JG, Goldenring JR, Wang TC. Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow-derived cells. Science. 2004;306:1568–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1099513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Varon C, Dubus P, Mazurier F, Asencio C, Chambonnier L, Ferrand J, Giese A, Senant-Dugot N, Carlotti M, Mégraud F. Helicobacter pylori infection recruits bone marrow-derived cells that participate in gastric preneoplasia in mice. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:281–291. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McLarnon A. Helicobacter pylori: Bone-marrow-derived cells could cause gastric preneoplasia in chronic Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:4. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang C, Gu L, Deng D. Bone marrow-derived cells may not be the original cells for carcinogen-induced mouse gastrointestinal carcinomas. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shlush LI, Hershkovitz D. Clonal evolution models of tumor heterogeneity. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015:e662–e665. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.e662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Calderwood SK. Tumor heterogeneity, clonal evolution, and therapy resistance: an opportunity for multitargeting therapy. Discov Med. 2013;15:188–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chow KH, Shin DM, Jenkins MH, Miller EE, Shih DJ, Choi S, Low BE, Philip V, Rybinski B, Bronson RT, et al. Epigenetic states of cells of origin and tumor evolution drive tumor-initiating cell phenotype and tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4864–4874. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cabrera MC, Hollingsworth RE, Hurt EM. Cancer stem cell plasticity and tumor hierarchy. World J Stem Cells. 2015;7:27–36. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v7.i1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bessède E, Molina S, Acuña-Amador L, Dubus P, Staedel C, Chambonnier L, Buissonnière A, Sifré E, Giese A, Bénéjat L, et al. Deletion of IQGAP1 promotes Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric dysplasia in mice and acquisition of cancer stem cell properties in vitro. Oncotarget. 2016;7:80688–80699. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yong X, Tang B, Xiao YF, Xie R, Qin Y, Luo G, Hu CJ, Dong H, Yang SM. Helicobacter pylori upregulates Nanog and Oct4 via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to promote cancer stem cell-like properties in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016;374:292–303. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nam KT, Lee HJ, Sousa JF, Weis VG, O’Neal RL, Finke PE, Romero-Gallo J, Shi G, Mills JC, Peek RM Jr, Konieczny SF, Goldenring JR. Mature chief cells are cryptic progenitors for metaplasia in the stomach. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2028–2037.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fujii Y, Yoshihashi K, Suzuki H, Tsutsumi S, Mutoh H, Maeda S, Yamagata Y, Seto Y, Aburatani H, Hatakeyama M. CDX1 confers intestinal phenotype on gastric epithelial cells via induction of stemness-associated reprogramming factors SALL4 and KLF5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109:20584–20589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208651109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wan J, Zhou J, Zhao H, Wang M, Wei Z, Gao H, Wang Y, Cui H. Sonic hedgehog pathway contributes to gastric cancer cell growth and proliferation. Biores Open Access. 2014;3:53–59. doi: 10.1089/biores.2014.0001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Song Z, Yue W, Wei B, Wang N, Li T, Guan L, Shi S, Zeng Q, Pei X, Chen L. Sonic hedgehog pathway is essential for maintenance of cancer stem-like cells in human gastric cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhao X, Wang F, Hou M. Expression of stem cell markers nanog and PSCA in gastric cancer and its significance. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:442–448. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.3884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gong S, Li Q, Jeter CR, Fan Q, Tang DG, Liu B. Regulation of NANOG in cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:679–687. doi: 10.1002/mc.22340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aggarwal BB, Kunnumakkara AB, Harikumar KB, Gupta SR, Tharakan ST, Koca C, Dey S, Sung B. Signal transducer and activator of transcription-3, inflammation, and cancer: how intimate is the relationship? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171:59–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jiang YX, Yang SW, Li PA, Luo X, Li ZY, Hao YX, Yu PW. The promotion of the transformation of quiescent gastric cancer stem cells by IL-17 and the underlying mechanisms. Oncogene. 2017;36:1256–1264. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mohammed MK, Shao C, Wang J, Wei Q, Wang X, Collier Z, Tang S, Liu H, Zhang F, Huang J, et al. Wnt/β-catenin signaling plays an ever-expanding role in stem cell self-renewal, tumorigenesis and cancer chemoresistance. Genes Dis. 2016;3:11–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oshima H, Matsunaga A, Fujimura T, Tsukamoto T, Taketo MM, Oshima M. Carcinogenesis in mouse stomach by simultaneous activation of the Wnt signaling and prostaglandin E2 pathway. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1086–1095. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mao J, Fan S, Ma W, Fan P, Wang B, Zhang J, Wang H, Tang B, Zhang Q, Yu X, et al. Roles of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in the gastric cancer stem cells proliferation and salinomycin treatment. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1039. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hasegawa T, Yashiro M, Nishii T, Matsuoka J, Fuyuhiro Y, Morisaki T, Fukuoka T, Shimizu K, Shimizu T, Miwa A, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts might sustain the stemness of scirrhous gastric cancer cells via transforming growth factor-β signaling. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1785–1795. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fu Y, Li H, Hao X. The self-renewal signaling pathways utilized by gastric cancer stem cells. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317697577. doi: 10.1177/1010428317697577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Demitrack ES, Samuelson LC. Notch as a Driver of Gastric Epithelial Cell Proliferation. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;3:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Toh TB, Lim JJ, Chow EK. Epigenetics in cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:29. doi: 10.1186/s12943-017-0596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kubota E, Kataoka H, Aoyama M, Mizoshita T, Mori Y, Shimura T, Tanaka M, Sasaki M, Takahashi S, Asai K, et al. Role of ES cell-expressed Ras (ERas) in tumorigenicity of gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:955–963. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yashiro M, Yasuda K, Nishii T, Kaizaki R, Sawada T, Ohira M, Hirakawa K. Epigenetic regulation of the embryonic oncogene ERas in gastric cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2009;35:997–1003. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tomita H, Takaishi S, Menheniott TR, Yang X, Shibata W, Jin G, Betz KS, Kawakami K, Minamoto T, Tomasetto C, et al. Inhibition of gastric carcinogenesis by the hormone gastrin is mediated by suppression of TFF1 epigenetic silencing. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:879–891. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yoda Y, Takeshima H, Niwa T, Kim JG, Ando T, Kushima R, Sugiyama T, Katai H, Noshiro H, Ushijima T. Integrated analysis of cancer-related pathways affected by genetic and epigenetic alterations in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang LH, Choi YL, Hua XY, Shin YK, Song YJ, Youn SJ, Yun HY, Park SM, Kim WJ, Kim HJ, et al. Increased expression of sonic hedgehog and altered methylation of its promoter region in gastric cancer and its related lesions. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:675–683. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu D, Shin HS, Lee YS, Lee YC. miR-106b modulates cancer stem cell characteristics through TGF-β/Smad signaling in CD44-positive gastric cancer cells. Lab Invest. 2014;94:1370–1381. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu K, Ma L, Zhu J. miR4835p promotes growth, invasion and selfrenewal of gastric cancer stem cells by Wnt/βcatenin signaling. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:3421–3428. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ye J, Wu D, Wu P, Chen Z, Huang J. The cancer stem cell niche: cross talk between cancer stem cells and their microenvironment. Tumour Biol. 2014;35:3945–3951. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-1561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Korkaya H, Liu S, Wicha MS. Breast cancer stem cells, cytokine networks, and the tumor microenvironment. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3804–3809. doi: 10.1172/JCI57099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Quante M, Tu SP, Tomita H, Gonda T, Wang SS, Takashi S, Baik GH, Shibata W, Diprete B, Betz KS, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the mesenchymal stem cell niche and promote tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:257–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhu L, Cheng X, Shi J, Jiacheng L, Chen G, Jin H, Liu AB, Pyo H, Ye J, Zhu Y, et al. Crosstalk between bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts and gastric cancer cells regulates cancer stemness and promotes tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2016;35:5388–5399. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li Z, Rich JN. Hypoxia and hypoxia inducible factors in cancer stem cell maintenance. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2010;345:21–30. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]