Abstract

Aim:

‘Pharmacoepigenomics’ methods informed by omics datasets and pre-existing knowledge have yielded discoveries in neuropsychiatric pharmacogenomics. Now we evaluate the generality of these methods by discovering an extended warfarin pharmacogenomics pathway.

Materials & methods:

We developed the pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline, a scalable multi-omics variant screening pipeline for pharmacogenomics, and conducted an experiment in the genomics of warfarin.

Results:

We discovered known and novel pharmacogenomics variants and genes, both coding and regulatory, for warfarin response, including adverse events. Such genes and variants cluster in a warfarin response pathway consolidating known and novel warfarin response variants and genes.

Conclusion:

These results can inform a new warfarin test. The pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline may be able to discover new pharmacogenomics markers in other drug-disease systems.

Keywords: : anticoagulation PGx, cardiovascular PGx, GWAS

Background

Pharmacogenomics is poised for transformation by the epigenome

Pharmacogenomics variant discovery has prioritized the search for protein coding variants (CVs) with genetic association and biochemical methods [1]. With the sequencing of the human genome, the initial hope for immediate discovery of highly penetrant CVs for many phenotypes [2,3] did not bear out, both in pharmacogenomics and in many other fields [4]. And with the advent of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), pharmacogenomics phenotypes began to be investigated with this powerful new tool [5]. Although most available pharmacogenomics tests were and are based on highly penetrant CVs, GWAS studies have revealed that the bulk of genetic variation in drug response, like many other phenotypes, comes from noncoding regulatory variants which are cooperative and combinatoric [6].

The development of the broader field of genomics and genomic regulation has been extremely fruitful in the last decade, but the deployment of GWAS in pharmacogenomics variant discovery has lagged deployment in other disciplines [5], epigenomic interpretation of GWAS results has been underutilized [7], and the translation of GWAS results into clinical tests has been slower still in most areas [8–10]. Over the last decade, genome-wide methods have produced increasingly deep and broad atlases of both the genome and epigenome. Genomic atlases have included HapMap [11] and 1000 Genomes [12], while epigenome atlases have included ENCODE Phases I [13] and II [14], the Roadmap Epigenome Mapping Consortium [15], the International Human Epigenome Consortium [16] and the upcoming Human Cell Atlas [17]. Along with this, potent new techniques for probing the spatial and temporal genome have emerged, including time series omics analysis and spatial genome methods like Hi-C [18,19,20].

Analysis of data from these atlases and targeted experiments has produced a new paradigm of regulation in which the spatial genome and epigenome take a prominent role [15,18,21]. In this paradigm, gene transcription is the result of the convergence of a series of spatial and functional factors. It takes place in chromatin loops at the spatial union of topologically associating domains (TADs) containing genic promoters with TADs containing controlling enhancers and co-regulated genes in a transcription factory [18]. Such factories assemble prior to the initiation of transcription [22,23], at the edges of chromosome territories [18], in TADs localized to interior of the cell nucleus [21]. This process occurs with the aid of activating transcription factors and epigenomic marks [15], in a dynamic [24,25], cell type specific [18] manner, with different enhancers active in different cell types and tissue microenvironments, while some act in many or all cell types and tissues.

This model, which has developed along with increasingly powerful epigenomic measurement techniques [15] and imaging modalities [26], is yielding increasing predictive power and new insight in many areas. Genome-wide, multi-omics epigenomes (i.e., those which combine a number of complementary genome-wide epigenomic measurements) are now available on a genome-wide basis in many cell lines and tissues [15], and even in multiple physiological conditions in many cases. As a result of this, the epigenome is increasingly regarded like the reference genome: as a resource to be consulted for systems and loci of interest [17], rather than an unknown quantity to be queried experimentally in specific contexts.

This transition is rapidly revolutionizing variant discovery with the emergence of integrated multi-omics pipelines for variant discovery. These pipelines, which include HaploReg [27] and RegulomeDB [6], screen association regions from the genome for variants bearing important marks of epigenomic regulatory variants. These methods have allowed investigators to begin investigating at scale the over 90% of associated variants which are noncoding regulatory variants [6], and to get new and increasing value out of GWAS studies whose results were initially enigmatic [28–30].

The pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline: multi-omics variant discovery for pharmacogenomics

However, in pharmacogenomics, these insights have not as yet been broadly applied. Despite recent work showing that an epigenome, 4D nucleome-based variant discovery and validation approach can yield value in excess of traditional methods [31–33], this new era of ‘pharmacoepigenomics’ [34,35] is still in its infancy. Indeed, much pharmacogenomics variant discovery still proceeds along traditional lines involving the search for CVs to be designated as star (*) alleles, with a particular emphasis on pharmacokinetic (PK) genes for absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME). Such genes have formed the focus for test development for response, dosing and adverse drug events (ADEs) and adverse drug reactions.

To aid the wider dissemination of these advanced methods in pharmacogenomics, we have created the pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline (PIP), an integrative multi-omics variant discovery pipeline designed specifically for next-generation pharmacogenomics and pharmacoepigenomics. It combines omics datasets (including epigenome compendia and phenotypically driven GWAS) with domain-specific knowledge (including key tissues and known significant genes). The PIP's variant discovery strategy is based on two separate workflows: a CV workflow based on traditional methods and an expression regulatory variant (ERV) workflow that integrates bioinformatics algorithms and omics datasets to screen and organize regulatory variants. These variants and their target genes are organized together at the end of the analysis to provide the input for downstream statistical analysis, gene-set enrichment and pathway analysis to clarify the genotype–phenotype relationships.

The ERV workflow is carried out with an overall model for combining multiple omics with pre-existing knowledge about drugs and disease (i.e., relevant tissues and candidate variants) to discover variants and pathways that have a causal influence in chosen phenotypes. It begins with lead SNPs from association studies and expands them in a population-specific manner with linkage mapping. After this, tissue-specific omics datasets are used to evaluate the regulatory function of the genomic regions around the variants, the dependence of that function on the status of the variants and the identity of likely target genes. Finally, variant-gene pairs passing all these tests are filtered and organized with pathway mapping and gene-set enrichment.

Nascent implementations of the ERV workflow have been used in several pharmacogenomics variant discovery experiments [31–33], in a number of drug-disease systems including lithium for bipolar disorder, valproic acid for traumatic brain injury and citalopram and ketamine for major depression [ga higgins, a allyn-feuer, bd athey, unpublished data]. The PIP is designed to introduce additional capabilities and further automation into such experiments.

The need for improved warfarin pharmacogenomics

Warfarin is an anticoagulant used for the prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in cardiac disease, postoperative recovery and other contexts involving the need for coagulation control [36]. An inhibitor of the vitamin K epoxide reductase enzyme complex (including VKORC1), it exhibits wide interindividual response variation [36]. Dose requirements to achieve therapeutic international normalized ratios (INR) vary as much as tenfold among patients [36]. Despite the recent availability of other oral anticoagulants, warfarin is still a commonly prescribed anticoagulant, and until 2015 this venerable drug was the most popular prescribed oral anticoagulant with about seven million office visit interactions resulting in a prescription [37].

Warfarin has complicated PK and pharmacodynamics (PD), with its influences on the action of a number of clotting factors each exhibiting a different half-life [36]. It is widely acknowledged that warfarin dosing requirements and other phenotypes exhibit a strong patient-specific genetic element. Factor-of-ten differences in typical dosing requirements based on alleles in CYP2C9, the primary metabolic enzyme of warfarin, are present on the package insert label [36], and data on association between warfarin requirements and other genetic loci have proliferated (Table 1 & Table 2). There have been multiple attempts to provide clinicians with genotype-guided dosing algorithms based typically on genotypes of VKORC1 and CYP2C9 [38], and in some cases CYP4F2 and GGCX. Despite the strength of variation in these key genes, there is a ‘missing heritability’ problem: identified loci in these genes account for only 30–50% of the predictive power implied by heritability estimates [38]. Current-generation tests use only variants in these genes, and almost all use the same three SNPs: rs1799853, rs1057910 and rs9923231 (a promoter SNP for VKORC1).

Table 1. . Genome-wide association study input studies for the warfarin experiment.

| PMID | Phenotype class | Phenotype | Sample size | Population ancestry | SNPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18535201 | Response | Warfarin maintenance dose | 555 | European | 3 |

| 19300499 | Response | Warfarin maintenance dose | 1641 | European | 4 |

| 20833655 | Response | Warfarin maintenance dose | 1952 | Japanese | 5 |

| 23755828 | Response | Warfarin maintenance dose | 965 | African–American | 1 |

| 26265036 | Response | Warfarin maintenance dose | 2967 | Brazilian, European, Japanese, African American | 16 |

| 22443383 | ADEs | Hemostatic factors and hematological phenotypes | 951 | European | 9 |

| 23381943 | ADEs | End-stage coagulation | 2100 | European | 23 |

| 24357727 | ADEs | Thrombin-generation potential phenotypes | 3224 | European | 4 |

| 19278955 | Disease/background | Venous thromboembolism | 4884 | European | 1 |

| 20212171 | Disease/background | C4b binding protein levels | 352 | European | 1 |

| 20303064 | Disease/background | Activated partial thromboplastin time | 1431 | European | 3 |

| 21980494 | Disease/background | Venous thromboembolism | 2652 | European | 4 |

| 22216198 | Disease/background | Anticoagulant levels | 397 | European | 8 |

| 22701019 | Disease/background | Factor XI | 997 | European | 0 |

| 22703881 | Disease/background | Prothrombin time | 3569 | European | 2 |

| 22703881 | Disease/background | Activated partial thromboplastin time | 11851 | European | 9 |

| 22672568 | Disease/background | Venous thromboembolism | 5787 | European and other | 5 |

| 23267103 | Disease/background | Coagulation factor levels | 3250 | European | 7 |

| 23509962 | Disease/background | Venous thromboembolism (SNP × SNP interaction) | 4291 | European | 37 |

| 23650146 | Disease/background | Venous thromboembolism | 51266 | European | 8 |

| 25240745 | Disease/background | Mitochondrial DNA levels | 386 | European | 21 |

| 25772935 | Disease/background | Venous thromboembolism | 65734 | European | 10 |

| 22550155 | Disease/background | Platelet thrombus formation | 241 | European, African–American | 6 |

A total of 23 associations from 22 genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [39–60] met the criteria for inclusion in the warfarin experiment, and their significant associations were rendered into the MVF and organized into phenotypic classes, along with 23 additional variants annotated by the Pharmacogenomics Knowledge Base (PharmGKB®) [61]. The 23 additional variants included all variants annotated by the PharmGKB as of September 2016, with a significant association with warfarin response, and were not already included in the list of variants identified from GWAS. Population descriptions are taken from the summary annotations in the original papers and the GWAS Catalog [62] , but in the PIP input files they are represented in 1000 Genomes format to replicate the detailed descriptions in the original papers as precisely as possible. Although they represent a variety of ancestries, European ancestry predominated among 17 out of 22 (77%) of the study populations.

ADE: Adverse drug event; MVF: Master variant file; PIP: Pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline; PMID: PubMed ID.

Table 2. . Tissue files used in the lithium and warfarin experiments.

| Tissue | ENCODE | REMC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium | |||

| Frontal lobe | Brain_Mid_Frontal_Lobe | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Insula | Brain_Cingulate_Gyrus | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Temporal cortex | Brain_Inferior_Temporal_Lobe | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Cingulate cortex | Brain_Cingulate_Gyrus | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Amygdala including_ amygdalo-hippocampal transition area |

Brain_Inferior_Temporal_Lobe | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Hippocampal formation including parahippocampal gyrus | Brain_Hippocampus_Middle | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Anterior caudate and putamen | Brain_Anterior_Caudate | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Thalamus, right | Brain_Anterior_Caudate | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Fusiform cortex, angular gyrus | Brain_Angular_Gyrus | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Motor cortex, substantia nigra, cerebellum | Brain_Substantia_Nigra | H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Hypothalamus | Fetal_Brain_Female Fetal_Brain_Male |

H1-hESC:SK-N-SH | |

| Warfarin | |||

| Tissue | ENCODE | REMC | GTEx |

| Liver | Adult_Liver: HepG2_Hepatocellular_Carcinoma | HepG2:liver:hepatocyte:right lobe of liver | Liver |

| Vasculature | Aorta: HUVEC_Umbilical_Vein_Endothelial_Cells | Endothelial cell of umbilical vein:dermis blood vessel endothelial cell:pulmonary artery endothelial cell:endothelial cell of coronary artery: aorta:thoracic aorta endothelial cell:vein endothelial cell:lung microvascular endothelial cell | Artery – Tibial: Artery – Coronary: Artery – Aorta |

| Small intestine | Fetal_Intestine_Small:Small_Intestine | Small intestine:Caco-2:jejunum | Small Intestine – Terminal Ileum |

The tissue file coding used in the lithium and warfarin PIP experiments, respectively. The first column contains natural language names for the tissues, while subsequent columns contain colon-delimited consortium ontology codes for related tissues and cell lines. The lithium experiment does not have tissue codes for GTEx because annotation of gene expression mapping was done manually with Allen Brain Atlas in situ hybridization data [63] in this experiment, as described herein.

PIP: Pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline.

Partially because of this, these tests have achieved only limited success despite intensive development and validation effort. Despite hopes that two large trials (EU-PACT [64] and COAG [65]) would report good results, their appearance in the same issue of the NEJM did not bear out such hopes. COAG reported no difference in time within the therapeutic range, and EU-PACT reported a difference, but only compared with fixed starting doses with subsequent adjustment, not to initial dosing methods based on clinical indications that represent the real-world alternative to genetic dosing. Neither trial was powered to report a difference in bleeding and embolism events. Subsequently, a published meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials of warfarin pharmacogenomics dosing algorithms versus manual dose determination showed that current-generation tests using VKORC1 and CYP2C9 offer no improvement in time within the therapeutic range, percentage of patients with high INR or bleeding and coagulation events [66].

Since the conclusion of these trials, expert comment has indicated a consensus that such algorithms do not add clinical value relative to dosing on the basis of clinical indications, despite their predictive power [67,68]. Although the recent GIFT randomized controlled trial of genomic warfarin dosing found that genome-guided dosing provided a significant benefit in the composite end point of major bleeding, INR of four or greater, venous thromboembolism or death [69], the generalizability of the study's results is limited. GIFT had narrow inclusion criteria: patients aged 65 years or older initiating warfarin for elective hip or knee arthroplasty. Those patients are at higher risk, and thus the generalizability of these results to larger patient populations and indications is debatable.

Despite their predictive power, such tests have failed to deploy in mainstream clinical practice. This experience suggests that new lines of research should be opened, such as the application of advanced genomic methods, to discover new variants, recover missing heritability and develop a new generation of tests which can add value relative to dosing by clinical indications.

Materials & methods

The pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline

The PIP uses lead variants from GWAS and candidate gene studies to find genetically linked permissive candidate variants (PCVs), using data from the 1000 Genomes Project for populations matched to the source studies. These variants are evaluated by two separate workflows: the ERV workflow for regulatory variants and the CV workflow for CVs. The ERV workflow evaluates the PCVs in disease-relevant tissues for DNA methylation, transcription factor binding, histone marks, DNase I hypersensitivity, chromatin state, quantitative trait loci (QTLs) and transcription factor binding site disruption using tissue-specific omics datasets. The CV workflow finds common nonsynonymous CVs within the pool of PCVs. Both sets of variants are mapped back to their host genes using RefSeq [70], and screened for expression in relevant tissues. The final output variants and their host genes are subjected to pathway analysis in Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis (IPA®; Qiagen GMBH) [71], offering an additional level of screening along with mechanistic insight for subsequent pharmacogenomics test development.

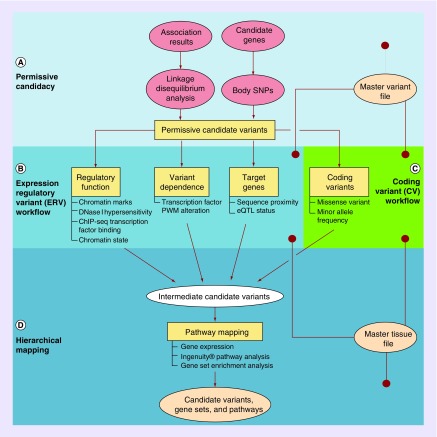

The methods of the PIP are shown in Figure 1. The PIP is based on the methods of our previous paper on lithium pharmacogenomics [32]. We performed two experiments with this pipeline. First, a reproduction of the lithium experiment with a restricted PIP feature set to replicate these methods to validate the initial pipeline by reproducing our lithium pathway. Second, a new experiment in the pharmacogenomics of warfarin using the full feature set to investigate whether the PIP may add value to a well-studied area of pharmacogenomics.

Figure 1. . Schematic of the pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline.

(A) The permissive candidacy portion of the PIP. GWAS lead SNPs and known significant genes for the phenotype of interest are encoded by the user in an MVF and expanded by population-specific linkage and body SNP mapping, respectively, to generate a list of permissive candidate variants (PCVs). (B) The ERV workflow. All of the PCVs are evaluated as putative regulatory SNPs using tissue-specific omics data on phenotype-relevant tissues encoded by the user in an MTF. They are evaluated according to the regulatory function of the chromatin state segment in which they reside, the dependence of that regulatory function on the variant allele and the presence of identifiable target gene relationships. (C) The coding variant (CV) workflow. In the CV workflow, all the PCVs are analyzed to investigate whether they are nonsynonymous CVs with a meaningful minor allele frequency. (D) The hierarchical mapping portion of the PIP. Variants passing either workflow (intermediate candidate variants) are associated with target genes, and those expressed in relevant tissues (per the MTF) are subjected to pathway mapping and gene-set enrichment in IPA®. Gene sets associated with significant and related pathways are regarded as substantive, and the variants influencing them (regulatory and coding) are considered candidate variants.

ERV: Expression regulatory variant; GWAS: Genome-wide association study; IPA®: Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis; MTF: Master tissue file; MVF: Master variant file; PIP: Pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline.

Construction of input files for lithium & warfarin PIP experiments

A PIP experiment begins with the input of associated lead variants in the form of a master variant file (MVF) which contains the refseq ID of the variant, the populations in which the original association was derived using 1kG Phase III population codes, and the PubMed ID of the study in which the association was derived.

PIP experiments were undertaken for lithium/bipolar disorder (BPD) and warfarin/anticoagulation, beginning with the construction of MVFs. For the warfarin experiment, a literature review in September 2016 identified 23 GWAS on warfarin response and other pharmacological phenotypes of warfarin, venous thromboembolism risk and baseline anticoagulant protein levels in healthy patients. Joint analysis of studies on related phenotypes, and overlap between disease risk and pharmacogenomics variants, are known phenomena from previous work. In addition, we added 23 variants annotated by PharmGKB®, yielding a total of 204 SNPs. The input studies for the warfarin experiment are summarized in Table 1.

The warfarin experiment began with input data from populations all over the world, including European, east Asian, south Asian, African and American cohorts. Population-specific associations from these groups were interpreted in the context of other population-specific input data, from the worldwide genome catalog of 1000 Genomes. Population descriptions are taken from the summary annotations in the original papers and the GWAS Catalog [62], but in the PIP input files are represented in 1000 Genomes format to replicate the detailed descriptions in the original papers as precisely as possible.

The various consortium data (ENCODE, REMC) and ChromHMM [72] chromatin states are imported for relevant tissues, with the relevant tissues being supplied in the format information for each consortium separately, for a unified set of tissues, in a master tissue file (MTF). The MTF is designed for each experiment to contain the set of tissues which are relevant to the particular drug-disease system under investigation, so that tissue-specific omics data may be used in the experiment. Information on the relevant chromatin marks and transcription factors was imported in a series of transcription factor (TF) and chromatin mark whitelist files containing metadata codes in the formats of each of the consortia.

MTFs were constructed for both experiments. The warfarin MTF included the human liver (site of warfarin metabolism), vasculature (site of action) and small intestine (site of absorption, a known variable in response and metabolism). These were represented by a mixture of cell line and tissue samples in the ENCODE, REMC and GTEx datasets, but a complete epigenome with methylation, DNase accessibility, all core histone marks and many TF-binding tracks was available in all tissues.

With the MVFs and MTFs generated for the lithium and warfarin experiments, the PIP was used to conduct its analysis.

Permissive candidate generation & variant annotation

Generation and annotation of PCVs occurs in the following manner:

Linkage disequilibrium mapping is performed in the PLINK software package [73], version 1.9 [74], with the 2 May 2013 (latest) release of 1000 Genomes consortium Phase III data. For each of the SNPs in the MVF, PLINK computes LD coefficients and outputs a set of all cis and trans variants that achieve R^2 ≥ 0.8 linkage with the input variant. These variants constitute the set of PCVs.

Chromatin state annotation is performed with the version of ChromHMM results available in the Washington University (WUSTL) epigenome browser [75] as of April 2016. Chromatin mark information on a number of indicative marks along with DNase accessibility measurements, TF binding and methylation (currently not used in scoring) are assayed using ENCODE and REMC data in the relevant marks and the relevant tissues as rendered in the MTF and whitelist files.

TFBS disruption data are assessed using TFM-scan [76] on 23-bp-per-side hg19 sequences on reference and alternate alleles from the source SNPs, using integer-converted data from the PWM library used in HaploReg [27], and requiring a threshold crossing or 10-point difference in score between reference and alternate alleles for a qualifying position weight matrix (PWM), as a measure of significance.

QTL data were imported from eight sources: the HaploReg QTL database [27], SeeQTL [77], MuTHER [78], GTEx [79], Shi et al.'s meQTLs [80], McClay et al.'s meQTLs [81], Banovich et al.'s meQTLs [82] and GeneVar [83]. Gene annotations were retrieved from the latest build of RefSeq in hg19.

Gene expression data were retrieved from the latest build of GTEx [79], and from the Allen Brain Atlas [63].

The CV workflow located all nonsynonymous CVs among the PCVs using dbSNP data, then screened them for minor allele frequency with 1000 Genomes data on all human populations, using a MAF cutoff of 0.01.

Variant scoring, expression testing & pathway analysis

Scoring proceeded according to Figure 1, with SNPs being required to pass all of the separate thresholds in each of the individual portions of either one of the two workflows (ERV and CV) to proceed. Then, their host genes must pass gene expression testing in relevant tissues with a twofold coverage threshold in order to reach the final gene list. All of these steps are undertaken on the Flux computing cluster at the University of Michigan. Finally, the gene list is analyzed with IPA.

Lithium PIP experiment: (mostly) same methods as original experiment

The two experiments were conducted with slightly different feature sets. The warfarin experiment used the full feature set, while the lithium experiment used a restricted feature set designed to match the semi-automated analysis from our 2015 paper, including no use of gene bodies as candidate region inputs, no CV workflow, expression analysis performed manually with Allen Brain Atlas in situ hybridization data on brain tissue and the use of biochronicity analysis to screen genes.

The lithium MVF was constructed to contain precisely the set of input variants originally used in the lithium experiment previously published, a total of 108 SNPs. The lithium MTF included the same tissues used in the original lithium experiment; BPD-relevant brain regions plus the human liver. The lithium MTF does not feature GTEx data because the restricted feature set for this experiment used manual gene expression analysis with Allen Brain Atlas in situ data in order to replicate the original lithium experiment. The tissue files for both experiments are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. . Output genes and SNPs of warfarin pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline experiment.

|

Despite this effort, the lithium experiment feature set of the PIP does not fully match the original experiment [32]. Several obstacles were encountered in which subtle differences in methods were necessitated by database deprecation, ambiguities in the documentation of available literature methods, and ambiguities in versioning of online resources. These obstacles included:

LD mapping methods: in the original paper, LD mapping was performed in HaploReg v4.1 [27], which uses the Phase I cohort of the 1000 Genomes project [12] as its LD mapping cohort. However, this tool was developed after the Phase III analysis results became available for this cohort, and it is unclear if they used the Phase I variant calls, or Phase III variant calls. We elected to use the Phase III cohort and population stratifications with the Phase III variant calls, because they are the most accurate;

Switch in QTL databases: the GeneVar [83] QTL database we used in the original analysis is no longer available in its full form. We have contacted the original authors and they have not responded. Because of this, we have been forced to seek supplemental databases in addition to the partial GeneVar database still available, as described below.

PWM integer approximation

The PIP uses the same database of PWMs that was used by HaploReg [27] during the initial lithium analysis, and scores them against the flanking sequences using the same software, TFM-Scan [76]. However, the PWM matrices available for bulk download are in probability format, and TFM-Scan presents warnings about accuracy when using probability matrices. It expects frequency matrices. We do not know if HaploReg used the probability matrices and (possibly) suffered inaccuracies, or if they have copies of the matrices in natively integer format which they have not made available, or if they converted the probability matrices to integer. We have elected to convert the probability matrices to frequency matrices, but because of rounding, this is imperfect and may introduce small errors.

Results

Lithium replication experiment: more significant pathway, more genes & variants

To demonstrate the ability of the PIP to replicate the results of previous integrative omics methods in pharmacoepigenomics variant discovery, we first undertook a PIP experiment to replicate the findings of our 2015 paper on lithium [32], as a positive control. The feature set of the PIP used for this experiment was restricted to match that of the previous experiment, as described in the methods.

The lithium experiment yielded a total of 1727 PCVs, of which a total of 78 passed the entire set of filters. These results differ from and expand on the results of the original lithium analysis. Although the original experiment identified 19 SNPs in 10 genes, the new experiment identified 17 out of 19 original SNPs, and all 10 original genes plus more SNPs in these and 2 more genes for a total of 78 SNPs in 12 genes. These are the ten genes from the original lithium paper, with the addition of HTR1A and TNIK, both of which appeared in the glutamatergic lithium pathway called by IPA in the original lithium paper.

Because of the factors mentioned in the methods, as well as imprecisions in the manual steps in the original lithium experiment, the lithium results differ subtly from those of the original experiment. This underscores the importance of using versioned, locally stored versions of all databases in bioinformatics experiments to allow reproducibility. In addition, however, the automated analysis recovers additional genes from the same pathway in the lithium experiment, emphasizing the utility of automated workflows with advanced functionality.

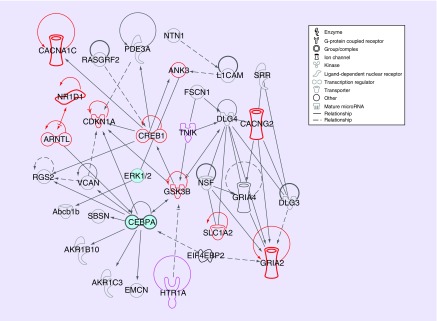

Thus, we reproduce the glutamatergic pathway for lithium response with the PIP, as reflected in Figures 2 & 3. IPA calls the same pathway for both the 10 genes discovered in the original experiment and the expanded 12-gene set. The pathway also includes 22 additional genes not discovered in either experiment but used to connect them in the pathway mapping functionality of IPA. The two pathways differ only in IPA's inclusion of a group of miRNAs in the old pathway and not in the new, which is the result of an IPA database change. The PIP recovers the same pathway as the original experiment.

Figure 2. . The pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline reproduces glutaminergic pathway for lithium response with two additional genes.

The same lithium pathway discovered by both manual and pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline (PIP) experiments. The ten genes discovered by both experiments (ANK3, ARNTL, CACNG2, CACNA1C, CDKN1A, CREB1, GRIA2, GSK3B, NR1D1, SLC1A2) are in red; two genes (HTR1A, TNIK) discovered by the PIP experiment only are in purple. The PIP discovers 78 candidate variants including 61 not discovered in the original lithium experiment. Gene classes and relationship types are designated with line types and gene glyphs as shown in the legend and described in the IPA® documentation [71].

IPA®: Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis.

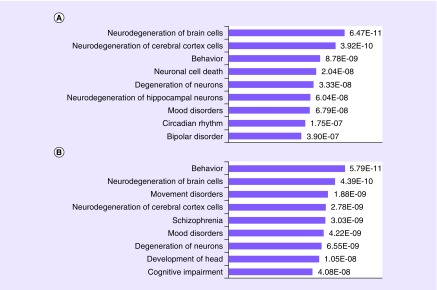

Figure 3. . Lithium pharmacogenomics gene Gene Set Enrichment Analysis results.

(A) Top diseases and functions detected by IPA® for ten genes detected in the original lithium experiment. (B) Top diseases and functions for the 12 genes detected in the PIP lithium experiment. Although there is significant overlap in the top nine hits for the two gene sets (five categories) there are some significant differences, demonstrating that the extra discerning power of the automated methods may be adding value relative to the semi-manual experiments.

IPA®: Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis; PIP: Pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline.

In addition to this, in the period of time between the execution of the 2015 lithium experiment and the publication of this manuscript, other groups have reported connections between lithium response and absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion and some of the genes we reported in this network [96,107].

Using substantially the same input data as the original lithium experiment [32], the PIP pipeline successfully identified the same glutamatergic pathway in the human brain and identified additional genes which are part of the same pathway. This constitutes a validation that the PIP replicates the discerning power of our previous semi-automated methods, and may function as a foundation for future development.

Warfarin experiment: known & novel variants form an enhanced & unified pathway

With the methods thus validated, we proceed to the results of the warfarin experiment in the PIP. The input variants from the warfarin study yielded a total of 4492 PCVs, which were analyzed for each of the criteria in the ERV and CV workflows. Of these PCVs, there were significant associations between the sets of SNPs passing some related modules in the PIP, and some modules were, in this experiment, significantly stricter than others. However, all the modules filtered out a meaningful number of SNPs as part of the overall process. This process is summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4. . Disposition of permissive candidate variant SNPs in the warfarin pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline experiment.

The disposition of SNPs within the workflows of the PIP during the warfarin experiment. In total, 190 input SNPs expand to 4492 PCVs. After evaluating all of these PCVs, the ERV workflow outputs 186 regulatory SNPs mapping to 57 genes, of which 30 (bearing 66 SNPs) were expressed in relevant tissues in GTEx datasets. The CV workflow outputs 37 SNPs in 27 genes, of which 22 in 17 genes pass the expression test. These 87 genes in 41 SNPs were subjected to IPA® analysis, revealing a combined network of 31 genes bearing a total of 74 SNPs (53 regulatory and 21 coding), as shown in Table 2 & Figure 6.

CV: Coding variant; ERV: Expression regulatory variant; IPA®: Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis; PIP: Pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline.

The ERV and CV workflows identify a total of 223 SNPs, which were then mapped to their host and target genes, which were subjected to the expression test with GTEx data on tissues from the MTF. Of these 223 SNPs, 87 were located in 41 genes passing the expression test. Notable among them is the presence of classic and previously known warfarin response genes including CYP2C9, clotting factors and VKORC1.

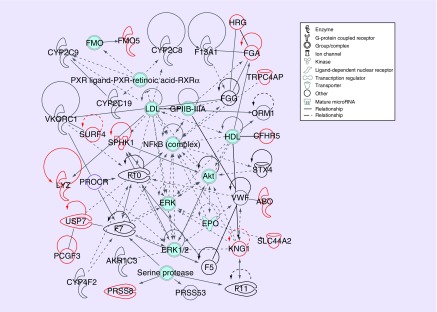

Next, we performed pathway analysis in IPA on this set of 41 genes. There are only four genes whose variants are used in current-generation warfarin pharmacogenomics tests: VKORC1, CYP2C9, CYP4F2 and GGCX. Despite the predictive power and clinical utility of these variants and the tests constructed with them, IPA does not connect them into a pathway, and previous warfarin literature has not conceptualized warfarin response in pathway terms. Despite this, and despite the typical pattern wherein IPA discovers many pathways of questionable relevance, this analysis yielded only two pathways, one of them with 31 genes and a particularly striking p-value of 1E-65 (as calculated by IPA). The gene list for this pathway is shown in Table 3, while the pathway network diagram is shown in Figure 5. It densely unites previously known warfarin response genes (including those not previously used in test design) with new genes.

Figure 5. . Warfarin pathway mapping results.

Pathway mapping results of warfarin response genes. IPA connects a warfarin pathway discovered by the PIP, with 31 genes and a p-value less than 1E-65. Genes include: ABO, AKR1C3, CFHR5, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP4F2, F5, F7, F10, F11, F13A1, FGA, FGG, FMO5, HRG, KNG1, LYZ, ORM1, PCGF3, PROCR, PRSS8, PRSS53, SLC44A2, SPHK1, STX4, SURF4, TRPC4AP, USP7, VKORC1 and VWF. Previously reported warfarin response genes are in black, and new genes are in red. Gene classes and relationship types are designated with line types and gene glyphs as shown in the legend and described in the IPA® documentation [71].

IPA®: Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis; PIP: Pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline.

This pathway may be considered the ‘canonical’ warfarin pathway based on the published literature base. It consolidates the bulk of discovered genes, particularly all but one of those previously known for warfarin response, including VKORC1, warfarin-metabolizing CYP enzymes and a collection of clotting factors. This includes the FGA and FGG fibrinogen subunits. Despite the fact that they operate as a complex and cannot function separately, FGG had been previously identified for warfarin response but FGA had not, whereas the PIP identifies both genes, which are located in the same TAD and are co-regulated.

Among previously known genes in this pathway, over 75% are highest expressed in liver, while 57% of newly discovered genes are highest expressed in the intestines or vasculature. Notably, a mixture of coding and regulatory SNPs is identified for both known and new genes.

The second pathway contains only one previously known warfarin gene (and that one, BCKDK, of disputed significance), does not show coagulation-related GSEA results, and its central elements are not of relevance. It may be considered an artifact.

Next, we processed the genes in the warfarin pathway with GSEA in IPA and GO. The results of the GSEA are shown in Figure 6. Warfarin and coagulation-related terms are prominent among the results, and many of the genes contributing to these identifications were not previously identified as warfarin related.

Figure 6. . Warfarin pharmacogenomics Gene Set Enrichment Analysis results.

(A) Top IPA® Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) hits for the warfarin gene pathway. (B) GO GSEA results for the warfarin pathway. Warfarin-related and coagulation-related gene sets are prominent among the results for the pathway in both GSEA systems, including bleeding, coagulation, clotting, thrombosis, hemorrhage and related gene sets. Many of the genes contributing to the identification of these gene sets were not previously discovered.

IPA®: Ingenuity® Pathway Analysis.

The PIP has identified many known genes for warfarin phenotypes, and added both new coding and regulatory SNPs for known genes, as well as new genes.

In addition to this, we investigated the warfarin input and output variants with DeltaSVM [108–110], evaluating their propensity to differentially induce DNase accessibility in the HepG2 liver cell line. Although the result SNPs contained a number of strong candidates by DeltaSVM, these candidates were not enriched relative to the candidates among the input set, nor were the mean and variance of the DeltaSVM scores significantly different between inputs and outputs. This implies that our existing variant dependence algorithms (PWM alteration) are mostly independent of DeltaSVM's predictive power, and that adding DeltaSVM or similar methods to the variant dependence portion of the pipeline (with appropriate changes to the scoring system) would add value to the pipeline.

The PIP is scalable: runtime & computational performance

For the warfarin experiment, total runtime and its division into the various components of the workflow are summarized in Figure 7. The total experimental runtime on the University of Michigan Flux cluster was about 14,300 node hours (each node using two six-core Intel Xeon X5650 processors running at 2.67 Ghz, with 48GB of RAM). Of this, the bulk was devoted to the initial LD calculations, QTL analysis and the retrieval of epigenome data from REMC datasets.

Figure 7. . Warfarin experiment runtime distribution by pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline module, in node hours.

The distribution of runtime among experimental modules in the PIP Warfarin experiment. Over 90% of total runtime was composed of just three pieces: Epigenome Roadmap data analysis, QTL analysis and PLINK linkage calculations. Of the remaining computational modules, shown in the smaller pie chart on the right, ENCODE data lookups and PWM analysis constitute the largest remaining steps. The CV workflow was computationally minimal.

CV: Coding variant; PIP: Pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline; QTL: Quantitative trait loci.

Although we anticipate substantial runtime improvements from code optimization in subsequent versions of the PIP, it is clear that this version is already computationally scalable for use in pharmacogenomics variant discovery in many systems. When sufficient cluster resources are available, it can finish running after about 6 hours of computation. Although REMC and QTLs are the largest contributors to total runtime, PLINK is a large contributor to parallel runtime because it is parallel on the level of input SNPs, not on the level of PCVs. With a sufficient number of nodes PLINK accounts for a third of total runtime, though not total computation.

Discussion

Warfarin pharmacogenomics

The discovery of a number of previously unknown candidate genes and SNPs for warfarin response, dosing and ADEs, including a unifying pathway with known variants, is a potential direction for a significant improvement in warfarin pharmacogenomics. This includes both additional variants controlling known warfarin response genes, and also putative new genes with associated variants. These variants should be included in the construction of next-generation predictive models for warfarin pharmacogenomics, and the mechanistic investigation of the newly discovered pathway may also be valuable.

The genes discovered in this experiment cluster into a pathway. In total, 31 genes and 74 SNPs, including 17 previously known genes [84–95,97–105], cluster into a coagulation pathway mainly made up of known genes, including clotting factors, CYP enzymes and vitamin K epoxide reductase. This may be considered the canonical warfarin pathway, although it appears not to have been explicitly described previously. Thus, the PIP has systematized and extended the previous literature into a more integrated picture. Because of the extensive pleiotropy observed with pharmacogenomics genes and variants, systematizing evidence is very important for integrative test design [111].

It is noteworthy that in the warfarin experiment, the PIP was successful in rediscovering both key PK and PD genes.

Although pharmacogenomics has traditionally used more variants in PK genes, as discussed in the introduction, PD variants have proved to be extremely potent in the instances where they do find clinical use, including VKORC1 promoter variants used in current-generation warfarin genetic tests, which are the most potent variants used in such tests. Thus, it is heartening to see extensive discovery of PD genes in the PIP, including extensive discovery of regulatory variants for PD genes. Discovery methods like the PIP may be able to aid the transition to make more use of PD genes in pharmacogenomics, as suggested previously [31,32,34].

PK genes discovered for warfarin include CYP2C9 and other key metabolic enzymes for warfarin. However, for PK genes, the PIP mostly discovered only CVs, and not regulatory variants. We suspect this may be the case for two reasons. First, the CYP loci have a complicated structure of homology with many similar genes in close proximity, which tends to confound both hybridization and linkage and sequence alignment [112–115], all of which are essential steps in the PIP and the omics assays which provide its source information. Second, however, the current version of the PIP locates target genes by sequence proximity, rendering it unable to find distal regulatory elements like those which control many facultative metabolic enzymes. It is anticipated, therefore, that subsequent PIP enhancements will enable better discovery of regulatory variants for PK genes.

Warfarin is a major anticoagulant, but in recent years a host of other anticoagulants including other vitamin K analog agonists as well as novel oral anticoagulants have been gaining in acceptance [37]. Many of these medications share known mechanistic elements with warfarin, and also have known differences in mechanisms [116,117]. Various drugs that modulate the coagulation system are used for other purposes [117,118], including clopidogrel, which is routinely prescribed on a chronic basis to reduce the risks of stroke and heart disease. And some SNPs discovered in the PIP experiment for warfarin have also appeared in association experiments for other anticoagulants, especially vitamin K antagonists. For example, rs2108622, a coding SNP in CYP4F2, which the PIP identifies as a warfarin response SNP, is also a response SNP for acenocoumarol [106]. A joint analysis of the pharmacoepigenomics properties of this broader collection of coagulation system-modifying drugs, integrating and comparing pathways and mechanisms, could be of real benefit to extend the breadth of future anticoagulation pharmacogenomics testing.

More broadly, these results indicate that the epigenome- and 4D nucleome-informed paradigm of pharmacogenomics that we described in our 2015 papers [31,32,34] may generalize beyond neuropsychiatry into cardiovascular pharmacogenomics and other domains. The genes and variants discovered with the PIP should be the subject of follow-up research in both pharmacogenomics test design and future anticoagulant drug development. Automated pharmacoepigenomics-based variant discovery and investigation methods like the PIP should continue to be developed, with potential future application in pharmacogenomics over the coming years.

Validation & extension of the pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline

Our successful reproduction of the results of the lithium experiment with the PIP demonstrates that reproducibility in bioinformatics experiments depends closely on adherence to important reproducibility principles. Reproduction of previous lithium results was complicated by elements of the original experiment like the inclusion of manual steps, consulting resources from external databases without retaining them or documenting precisely which tracks were consulted and the use of databases whose contents change in a unversioned manner. These lessons have been incorporated into the PIP with design features like the use of versioned, locally stored databases, the selection of resources and records in an algorithmic and reproducible manner and the retention of intermediate results and code. This ensures that PIP experiments are reproducible. Remaining challenges, including the use of the unversioned IPA database for pathway analysis, should be rectified in subsequent PIP refinements. Conversely, however, it is clear from our results that the automated pipeline offers better functionality than the semi-automated pipeline it was designed to reproduce.

It is possible to make pervasive use of machine learning in gauging the variant dependence of enhancer function. The current pipeline gauges variant dependence only with PWM measurements, but a number of machine learning algorithms have recently been published for gauging variant function, including DeltaSVM [108–110], methods of Nishizaki [7] and recently GKM-DNN [119–123]. We have performed testing with DeltaSVM indicating that its predictive power is ‘orthogonal’ to that of PWMs, and would add value, both by allowing rejection of variants that pass the current scoring system but do not show variant dependence with DeltaSVM, and rescue of variants that barely miss the current thresholds but exhibit strong variant dependence in DeltaSVM. The integration of some of these published methods would strengthen the PIP.

In addition, methods like the PIP may help alleviate a vexing issue in current pharmacogenomics and other genetic testing: inapplicability of some test results across populations. Sometimes genetic associations discovered with association testing may hold in the population from which the study populations were drawn (predominantly European, although increasingly Asian populations are being used in research conducted in Asia), but not in other populations [124–127]. In this case, only 3 of 23 studies included African populations. This has been an issue of comment both in the literature [128–131] and in the lay press [132 133]. Strategies for surmounting it have comprised including population-specific lead SNPs in test design, designing separate tests for different populations, including population-linked SNPs in test design, and various combinations of these methods [134,135]. Warfarin response and coagulation phenotypes in particular are an area in which certain populations, including African–Americans, have exhibited different response profiles and different GWAS lead SNPs from European populations [54,136].

The PIP and similar methods may help to resolve this problem. One mechanism by which such an effect may arise is when a GWAS lead SNP is only a tagging variant for an underlying effector SNP, and the LD relationship between these SNPs is population dependent. In such cases, the PIP, by evaluating the population of population-specific LD partners of the lead SNP, and finding effector SNPs within this population will sometimes enable tests to be designed on the basis of population-specific GWAS which will function predictively in a population-agnostic manner.

Methods like these may generalize in other drug-disease systems. PIP-style methods may identify trans-ethnic causal regulatory variants and recover missing heritability by interpreting association studies in the light of disease mechanisms and massive cohort omics. These high-quality novel variants may help to enable the development of new pharmacogenomics tests with greater predictive power and clinical benefit.

Summary points.

Pharmacoepigenomics methods, informed by omics datasets and published literature, have yielded discoveries in neuropsychiatric pharmacogenomics.

Pharmacogenomics is poised to be rapidly revolutionized by regulatory variant discovery driven by integrated multi-omics pipelines.

However, much pharmacogenomics variant discovery still proceeds along traditional lines involving the search for coding variants to be designated as star (*) alleles.

We have developed a pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline (PIP), an integrative multi-omics variant discovery pipeline designed specifically for next-generation pharmacogenomics and pharmacoepigenomics, and validated it using a positive control in lithium pharmacogenomics.

The PIP is based on 4D genome architecture and integrates bioinformatics algorithms and omics datasets along with pre-existing domain-specific knowledge derived from the published literature to screen and organize pharmacogenomics regulatory variants and a separate module to find nonsynonymous coding variants.

Despite large genetic influence on dosing, pharmacogenomics tests in warfarin have failed to find wide use because the three commonly used SNPs in two key genes account for ∼30% of the heritability of response.

Using the PIP to analyze the results of 23 genome-wide association studies on warfarin-related phenotypes, we identified known and novel putative pharmacogenomics variants and genes for warfarin response, including some adverse event markers.

Such genes and variants appear to cluster in a warfarin response pathway containing known warfarin response genes, adding additional variants altering the protein sequence of or putatively regulating these genes, and also adding new genes and variants.

Multi-omics pipelines for pharmacogenomics screening may further enhance our understanding of other drug-disease systems, and provide direction for the creation of new pharmacogenomics tests with improved patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank A Kalinin for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

A Allyn-Feuer was funded by NIH T32 Predoctoral training grant number 5T32GM070449–12. A Allyn-Feuer, A Ade, GA Higgins and BD Athey were supported by UM Medical School Departmental Funds. JA Luzum was supported by the NIH Loan Repayment Program (L30 HL110279) and U-M College of Pharmacy start-up funding. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Open access

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Black JL, O'Kane DJ, Mrazek DA. The impact of CYP allelic variation on antidepressant metabolism: a review. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2007;3(1):21–31. doi: 10.1517/17425255.3.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins FS, McKusick MD. Implications of the Human Genome Project for medical science. JAMA. 2001;285(5):540–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.5.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganguly NK, Bano R, Seth SD. Human genome project: pharmacogenomics and drug development. Indian J. Exp. Biol. 2001;39(10):955–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinshilboum R, Wang L. Pharmacogenomics: bench to bedside. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:739–748. doi: 10.1038/nrd1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giacomini KM, Yee SW, Mushiroda T, Weinshilboum RM, Ratain MJ, Kubo M. Genome-wide association studies of drug response and toxicity: an opportunity for genome medicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:1. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A review of pharmacogenomics genome-wide association study experiments and their impact and potential impact on both genetic testing and drug discovery, which argues that they should be used pervasively.

- 6.Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22(9):1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• An early multi-omics variant annotation pipeline, along with a persuasive argument for the importance of regulatory variants in phenotypes of biomedical interest.

- 7.Nishizaki SS, Boyle AP. Mining the unknown: assigning function to noncoding single nucleotide polymorphisms. Trends Genet. 2017;33(1):34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florez JC. Pharmacogenomics in Type 2 diabetes: precision medicine or discovery tool? Diabetologia. 2017;60(5):800–807. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giudicessi JR, Kullo IL, Ackerman MJ. Precision cardiovascular medicine: state of genetic testing. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017;92(4):642–662. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabbri C, Crisafulli C, Calabrò M, Spina E, Serretti A. Progress and prospects in pharmacogenetics of antidepressant drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2016;12(10):1157–1168. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2016.1202237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International HapMap Constortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–862. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The ENCODE Project Consortium. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kellis M, Wold B, Snyder MP, et al. Defining functional DNA elements in the human genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111(17):6131–6138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318948111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium. Kundaje A, Meuleman W, et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Human Epigenome Consortium. Stunnenberg HG, Hirst M. The International Human Epigenome Consortium: a blueprint for scientific collaboration and discovery. Cell. 2016;167(5):1145–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regev A, Teichmann S, Lander ES, et al. The human cell atlas. BioRxiv. 2017 Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao SS, Huntley MH, Durand NC, et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. 2014;159(7):1665–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A seminal paper in the history of Hi-C, the deepest available Hi-C maps, the genesis of loop domains and an important step in the understanding of the role of CTCF at topologically associating domain boundaries.

- 19.Mifsud B, Tavares-Cadete F, Young AN, et al. Mapping long-range promoter contacts in human cells with high-resolution capture Hi-C. Nat. Genetics. 2015;47:598–606. doi: 10.1038/ng.3286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin P, McGovern A, Orozco G, et al. Capture Hi-C reveals novel candidate genes and complex long-range interactions with related autoimmune risk loci. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:10069. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cremer T, Cremer M, Hübner B, et al. The 4D nucleome: evidence for a dynamic nuclear landscape based on co-aligned active and inactive nuclear compartments. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(20A):2931–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hug CB, Grimaldi AG, Kruse K, Vaquerizas JM. Chromatin architecture emerges during zygotic genome activation independent of transcription. Cell. 2017;169:216–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krijger PHL, de Laat W. Can we just say: transcription second? Cell. 2017;169:184–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H, Chen J, Muir LA, et al. Functional organization of the human 4D nucleome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112(26):8002–8007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505822112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen H, Seaman L, Liu S, Ried T, Rajapakse I. Chromosome conformation and gene expression patterns differ profoundly in human fibroblasts grown in spheroids versus monolayers. Nucleus. 2017;8(4):383–391. doi: 10.1080/19491034.2017.1280209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang S, Su JH, Beliveau BJ, et al. Spatial organization of chromatin domains and compartments in single chromosomes. Science. 2016;353(6299):598–602. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg v4: systematic mining of putative causal variants, cell types, regulators, and target genes for human complex traits and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D877–D881. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • An important multi-omics variant annotation pipeline and the source of some methods and datasets used in the pharmacoepigenomics informatics pipeline (PIP).

- 28.Fagny M, Paulson JN, Kuijjer ML, et al. A network-based approach to eQTL interpretation and SNP functional characterization. BioRxiv. 2016 Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tak YG, Farnham PJ. Making sense of GWAS: using epigenomics and genome engineering to understand the functional relevance of SNPs in non-coding regions of the human genome. Epigenet. Chromat. 2015;8:57. doi: 10.1186/s13072-015-0050-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farh KKH, Marson A, Zhu J, et al. Genetic and epigenetic fine mapping of causal autoimmune disease variants. Nature. 2014;518(7539):337–343. doi: 10.1038/nature13835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higgins GA, Allyn-Feuer A, Athey BD. Epigenomic mapping and effect sizes of noncoding variants associated with psychotropic drug response. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16(14):1565–1583. doi: 10.2217/pgs.15.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins GA, Allyn-Feuer A, Barbour E, Athey BD. A glutamatergic network mediates lithium response in bipolar disorder as defined by epigenome pathway analysis. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16(14):1547–1563. doi: 10.2217/pgs.15.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• One of the first published experiments with the methods underlying the PIP, and the source of the lithium results used as a positive control for the PIP.

- 33.Higgins GA, Georgoff P, Nikolian V, et al. Network reconstruction reveals that valproic acid activates neurogenic transcriptional programs in adult brain following traumatic brain injury. Pharm. Res. 2017;34(8):1658–1672. doi: 10.1007/s11095-017-2130-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins GA, Allyn-Feuer A, Handelman S, Sadee W, Athey BD. The epigenome, 4D nucleoma and next generation neuropsychiatric pharmacogenomics. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16(14):1649–1669. doi: 10.2217/pgs.15.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A review of the pharmacoepigenome and its use in discovering pharmacogenomics variants and developing pharmacogenomics tests restricted to neuropsychiatry, but now believed more general.

- 35.Higgins GA, Allyn-Feuer A, Georgoff P, et al. Mining the topography and dynamics of the 4D nucleome to identify novel CNS drug pathways. Methods. 2017;123:102–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.United States Federal Drug Administration. Highlights of prescribing information: coumadin (warfarin sodium) tablets, for oral use. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/009218s107lbl.pdf

- 37.Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC, Goldberger ZD. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am. J. Med. 2015;128(12):1300–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flockhart DA, O'Kane D, Williams MS, et al. Pharmacogenetic testing of CYP2C9 and VKORC1 alleles for warfarin. Genetics Med. 2008;10:139–150. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318163c35f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A summary of the two key PGx genes and three key variants used in most PGx testing for warfarin, including the recent randomized controlled trials cited below, from 10 years ago.

- 39.Cooper GM, Johnson JA, Langaee TY, et al. A genome-wide scan for common genetic variants with a large influence on warfarin maintenance dose. Blood. 2008;112(4):1022–1027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takeuchi F, McGinnis R, Bourgeois S, et al. A genome-wide association study confirms VKORC1, CYP2C9, and CYP4F2 as principal genetic determinants of warfarin dose. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(3):e1000433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cha PC, Mushiroda T, Takahashi A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies genetic determinants of warfarin responsiveness for Japanese. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010;19(23):4735–4744. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perera MA, Cavallari LH, Limdi NA, et al. Genetic variants associated with warfarin dose in African–American individuals: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2013;382(9894):790–796. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60681-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parra EJ, Botton MR, Perini JA, et al. Genome-wide association study of warfarin maintenance dose in a Brazilian sample. Pharmacogenomics. 2015;16(11):1253–1263. doi: 10.2217/PGS.15.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oudot-Mellakh T, Cohen W, Germain M, et al. Genome wide association study for plasma levels of natural anticoagulant inhibitors and protein c anticoagulant pathway: the MARTHA project. Br. J. Haematol. 2012;157(2):230–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.09025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams FM, Carter AM, Hysi PG, et al. Ischemic stroke is associated with the ABO locus: the EUROCLOT study. Ann. Neurol. 2013;73(1):16–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.23838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rocanin-Arjo A, Cohen W, Carcaillon L, et al. A meta-analysis of genome wide association studies identifies ORM1 as a novel gene controlling thrombin generation potential. Blood. 2014;123(5):777–785. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-529628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tregouet DA, Heath S, Saut N, et al. Common susceptibility alleles are unlikely to contribute as strongly as the FV and ABO loci to VTE risk: results from a GWAS approach. Blood. 2009;113(21):5298–5303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Buil A, Tregouet DA, Souto JC, et al. C4BPB/C4BPA is a new susceptibility locus for venous thrombosis with unknown protein S-independent mechanism: results from genome-wide association and gene expression analyses followed by case–control studies. Blood. 2010;115(23):4644–4650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Houlihan LM, Davies G, Tenesa A, et al. Common variants of large effect in F12, KNG1, and HRG are associated with activated partial thromboplastin time. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86(4):626–631. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Germain M, Saut N, Greliche N, et al. Genetics of venous thrombosis: insights from a new genome wide association study. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(9):e25581. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Athanasiadis G, Buil A, Souto JC, et al. A genome-wide association study of the Protein C anticoagulant pathway. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(12):e29168. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sabater-Lleal M, Martinez-Perez A, Buil A, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies KNG1 as a genetic determinant of plasma factor XI level and activated partial thromboplastin time. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012;32(8):2008–2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.248492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tang W, Schwienbacher C, Lopez LM, et al. Genetic associations for advanced partial thromboplastin time and prothrombin time, their gene expression profiles, and risk of coronary artery disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91(1):152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heit JA, Armasu SM, Asmann YW, et al. A genome-wide association study of venous thromboembolism identifies risk variants in chromosomes 1q24.2 and 9q. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2012;10(8):1521–1531. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Desch KC, Ozel AB, Siemieniak D, et al. Linkage analysis identifies a locus for plasma von willebrand factor undetected by genome-wide association. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(2):588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219885110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greliche N, Germain M, Lambert JC, et al. A genome-wide search for common SNP × SNP interactions on the risk of venous thrombosis. BMC Med. Genet. 2013;14:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang W, Teichert M, Chasman DI, et al. A genome-wide association study for venous thromboembolism: the extended cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Genet. Epidemiol. 2013;37(5):512–521. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez S, Buil A, Souto JC, et al. A genome-wide association study in the genetic analysis of idiopathic thrombophilia project suggests sex-specific regulation of mitochontrial DNA levels. Mitochondrion. 2014;18:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Germain M, Chasman DI, de Haan H, et al. Meta-analysis of 65,734 individuals identifies TSPAN15 and SLC44A2 as two susceptibility loci for venous thromboembolism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015;96(4):532–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Edelstein LC, Luna EJ, Gibson IB, et al. Human genome-wide association and mouse knockout approaches identify platelet supervillin as an inhibitor of thrombus formation under shear stress. Circulation. 2012;125(22):2762–2771. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.091462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Whirl-Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, et al. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;92(4):414–417. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.MacArthur J, Bowler E, Cerezo M, et al. The new NHGRI-EBI catalog of published genome-wide association studies (GWAS catalog) Nucl. Acids Res. 2017;45:D896–D901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sunkin SM, Ng L, Lau C, et al. Allen Brain Atlas: an integrated spatio-temporal portal for exploring the central nervous system. Nucl. Acids Res. 2013;41(D):D996–D1008. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pirmohamed M, Burnside G, Eriksson N, et al. A randomized trial of genotype-guided dosing of warfarin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2294–2303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kimmel SE, French B, Kasner SE, et al. A pharmacogenetic versus a clinical algorithm for warfarin dosing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;369:2283–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stergiopoulos K, Brown DL. Genotype-guided vs clinical dosing of warfarin and its analogues: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014;174(8):1330–1338. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kimmel SE. Warfarin pharmacogenomics: current best evidence. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2015;13(S1):S266–S271. doi: 10.1111/jth.12978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Johnson JA, Cavallari LH. Warfarin pharmacogenetics. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2016;25(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gage BF, Bass AR, Lin H, et al. Effect of genotype-guided warfarin dosing on clinical events and anticoagulation control among patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty: the GIFT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1115–1124. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• A consequential randomized controlled trial of a first-generation genetic dosing algorithm for warfarin, showing some statistically significant but limited results.

- 70.O'Leary NA, Wright MW, Brister JR, et al. Reference sequence (RefSeq) database at NCBI: current status, taxonomic expansion, and functional annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D733–D745. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kramer A, Green J, Pollard J, Jr, Tugendreich S. Causal analysis approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(4):523–530. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ernst J, Kellis M. ChromHMM: automating chromatin state discovery and characterization. Nat. Methods. 2012;9(3):215–216. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, et al. PLINK: a toolset for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analysis. Am. J. Human Genetics. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. doi: 10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou X, Lowdon RF, Li D, et al. Exploring long-range genome interactions using the WashU Epigenome Browser. Nat. Methods. 2013;10(5):375–376. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liefooghe A, Touzet H, Varre JS. Combinatorial Pattern Matching. Springer Publishing; NY, USA: 2006. Large scale matching for position weight matrices; pp. 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xia K, Shabalin AA, Huang S, et al. seeQTL: a searchable database for human eQTLs. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(3):451–452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Grundberg E, Small KS, Hedman ÅK, et al. Mapping cis- and trans-regulatory effects across multiple tissues in twins. Nat. Genetics. 2012;44:1084–1089. doi: 10.1038/ng.2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carithers LJ, Moore HM. The Genotype–Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2015;16:286. doi: 10.1089/bio.2015.29031.hmm. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shi J, Marconett CN, Duan J, et al. Characterizing the genetic basis of methylome diversity in histologically normal human lung tissue. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3365. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McClay JL, Shabalin AA, Dozmorov MG, et al. High density methylation QTL analysis in human blood via next-generation sequencing of the methylated genomic DNA fraction. Genome Biol. 2015;16:291. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0842-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Banovich NE, Lan X, McVicker G, et al. Methylation QTLs are associated with coordinated changes in transcription factor binding, histone modifications, and gene expression levels. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(9):e1004663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yang TP, Beazley C, Montgomery SB, et al. Genevar: a database and Java application for the analysis and visualization of SNP–gene associations in eQTL studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(19):2474–2476. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malatkova P, Sokolova S, Chocholoušová Havlíková L, Wsól V. Carbonyl reduction of warfarin: identification and characterization of human warfarin reductases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016;109:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wadelius M, Chen LY, Eriksson N, et al. Association of warfarin dose with genes involved in its action and metabolism. Hum. Genet. 2007;121(1):23–34. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0260-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen J, Shao L, Gong L, et al. A pharmacogenetics-based warfarin maintenance dosing algorithm from northern Chinese patients. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e105250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bare LA, Arellano AR, Tong CH, et al. Genetic variants of F11, statin use and venous thrombosis. J. Thromb. Haematost. 2011;9(6):1249–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Marsh S, King CR, Porche-Sorbet RM, Scott-Horton TJ, Eby CS. Population variation in VKORC1 haplotype structure. J. Thromb. Haematos. 2006;4(2):473–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bader LA, Elewa H. The impact of genetic and non-genetic factors on warfarin dose prediction in MENA region: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0168732. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang LS, Shang JJ, Shi SY, et al. Influence of ORM1 polymorphisms on the maintenance stable warfarin dosage. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;69(5):1113–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00228-012-1448-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Eriksson N, Wallentin L, Berglund L, et al. Genetic determinants of warfarin maintenance dose and time in therapeutic range: a RE-LY genomics substudy. Pharmacogenomics. 2016;17(13):1425–1439. doi: 10.2217/pgs-2016-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lind M, Boman K, Johansson L, et al. Von Willebrand factor predicts major bleeding and mortality during oral anticoagulant treatment. J. Intern. Med. 2012;271(3):239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]