Abstract

Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus (S. zooepidemicus) is mostly known as an opportunistic pathogen found in horses and as a rare human zoonosis. An 82-year-old male, who had daily contact with horses, was admitted in a septic condition. The patient presented with dyspnea, hemoptysis, impaired general condition, and severe pain in a swollen left shoulder. Synovial fluid from the affected joint and blood cultures showed growth of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus. Transesophageal echocardiography showed a vegetation on the aortic valve consistent with endocarditis. Arthroscopic revision revealed synovitis and erosion of the rotator cuff. Technetium-99m scintigraphy showed intense increased activity in the left shoulder, suspicious of osteitis. The infection was treated with intravenous antibiotics over a period of five weeks, followed by oral antibiotics for another two months. The patient recovered without permanent sequelae.

1. Introduction

Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus is classified as a beta-haemolytic, Lancefield group C streptococcal bacteria [1]. The bacterium is associated with opportunistic infections in horses, especially in the upper respiratory tract in horses, but can also cause infections in several other animals [1–3]. Transmission to humans is rare and is related to consumption of unpasteurized dairy products or contact with domestic animals, especially horses [1, 3]. Manifestation of the bacteria in humans is often associated with serious disseminated infections such as meningitis, glomerulonephritis, or sepsis [4], which also is the case in the present report. However, it can also be localised to one organ as pneumonia or purulent arthritis [5]. Previous reports of endocarditis and purulent arthritis due to S. zooepidemicus have only been documented in, respectively, 17 and 16 case reports (Tables 1 and 2). This is to our knowledge the first reported case of infective endocarditis in Scandinavia caused by S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus. We hereby seek to bring attention to S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus as a zoonotic pathogen, and the importance of clinical awareness on characteristic anamnestic information, hence animal contact when treating patients with sepsis or bacteraemia.

Table 1.

Published cases with endocarditis due to Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus.

| Number | Age/sex | Year/nationality | Diagnosis | Comorbidity | Contamination | Antibiotic therapy | Pattern of resistance | Duration of treatment | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 83/M | 2016, Faroe Islands | Endocarditis, purulent arthritis, suspected osteomyelitis, sepsis | DMII, HD, IHD, low malignant prostate cancer | Horses | IV cefuroxime, benzylpenicillin, gentamicin (in total 5 days), oral amoxicillin, and rifampin | Sensitive to penicillin, ampicillin, cefotaxime, erythromycin, and clindamycin | 12 weeks and 4 days | Recovered | Present case |

| 2 | 59/F | 2009, Canada | Meningitis, mitral endocarditis, endophthalmitis | AH, DMII, dyslipidemia, IHD, chronic renal failure, obesity, left ophthalmic vein thrombosis, ostium primum atrial septal defect, hypothyroidism, primary hyperparathyroidism and anemia | No relation to unpasteurised milk products. Her husband had daily contact with healthy horses | IV ceftriaxone and rifampin | Susceptible to all tested antibiotics according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standard Institute criteria | 6 weeks | Blindness | [4] |

| 3 | 70/F | 2003, Spain | Pneumonia, endocarditis, bacteraemia | None | Milk-borne outbreak | Beta-lactam agent | Sensitive to penicillin, erythromycin, vancomycin, rifampin, and levofloxacin, but resistant to clindamycin and tetracycline | Unknown | Disorientation to time and place | [3] |

| 4 | 73/M | Spain | Bacteraemia, endocarditis | AH, dyslipidemia, mechanical aortic valve replacement | Contact to stillborn foal two weeks before admission | Penicillin (6 weeks) and gentamicin (first 2 weeks) | Unknown | 6 weeks | Recovered | [6] |

| 5 | 2012, France | Bacteraemia, endocarditis | Pituitary adenoma, mechanical aortic valve | Unknown | Amoxicillin and gentamicin | Sensitive to beta-lactamins, macrolides, chloramphenicol, co-trimoxazole, glycopeptides, and rifampin, but resistant to tetracycline | 6 weeks | Recovered | [7] | |

| 6 | 79/M | 2010, England | Bacteraemia, endocarditis | None | Horse manure | Benzylpenicillin and vancomycin | Unknown | 6 weeks | Recovered | [8] |

| 7 | 57/M | 2011, Finland | Sepsis, meningitis, endocarditis | Aortic valve insufficiency | Horses | Penicillin (5 weeks) and gentamicin (10 first days) | Sensitive to erythromycin, clindamycin, penicillin, vancomycin, and cephalexin | 5 weeks | Recovered | [1] |

| 8 | 58/F | 1980's, China | Bacteraemia, endocarditis | None | No relation to horses or unpasteurised milk | Benzylpenicillin | Unknown | Unknown | Recovered | [9] |

| 9 | 51/M | 1982, unknown | Bacteraemia, endocarditis | Rheumatic HD | Unknown, but was a farmer | IV penicillin (4 weeks) and IM streptomycin (2 weeks) | Unknown | 4 weeks | Recovered | [10] |

| 10 | 52/F | 1984, England | Sepsis, bacteraemia, endocarditis | Unknown | A milk-borne outbreak | Penicillin and cephalosporin | Unknown | 4 weeks | Impairment of peripheral flow in one arm | [11] |

| 11 | 73/M | 1984, England | Sepsis, bacteraemia, endocarditis, meningitis | IHD | A milk-borne outbreak | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Died | [11] |

| 12 | 79/M | 1984, England | Sepsis, bacteraemia, endocarditis | A milk-borne outbreak | Cephalosporin, ampicillin, and metronidazole | Unknown | 2 weeks | Died | [11] | |

| 13 | 81/M | 1979, England | Bacteraemia, endocarditis, cholecystitis | Chronic rheumatic HD | Unknown | Oral ampicillin, IV benzyl penicillin (3 weeks and 3 days) and gentamicin (first 10 days), changed to oral amoxicillin (2 weeks) | Unknown | 5 weeks and 3 days | Died | [12] |

The table includes 12 of the 17 cases, exclusive the present cases. The last three cases are not included because the information in the articles was either impossible to get access to or not detailed enough to fulfil the table: two cases of endocarditis due to S. zooepidemicus from the article “Endocarditis due to group C streptococci according to Group C streptococcal bacteremia: analysis of 88 cases.” One case in “Prolonged fever Streptococcus equi spp. zooepidemicus (endocarditis aortic complicated with mycotic aneurysm infrarenal).” The article “Group C streptococcal infections associated with eating home cheese–New Mexico” describes one case with endocarditis. AH: arterial hypertension; IHD: ischemic heart disease; HD: heart disease; DMII: diabetes mellitus type II; IV: intravenous; IM: intramuscular injection.

Table 2.

Published cases with septic arthritis due to Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus.

| Number | Age/sex | Year/nationality | Diagnosis | Comorbidity | Contamination | Antibiotic therapy | Pattern of resistance | Duration of treatment | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60/M | 2008, Germany | Purulent arthritis | Chronic back pain | Horses (cutaneous wound) | IV amoxicillin with clavulanic acid, gentamicin | Tetracycline | 5 weeks and 4 days | None | [13] |

| 2 | 72/F | 2003, Spain | Septic arthritis | None | Milk-borne outbreak | Beta-lactam agent | Sensitive to penicillin, erythromycin, vancomycin, rifampin, and levofloxacin, but resistant to clindamycin and tetracycline | Unknown | Limited mobility | [3] |

| 3 | 79/M | 2003, Spain | Bacteraemia and septic arthritis | DMII, AH, HD | Milk-borne outbreak | Beta-lactam agent | Same as case number 3 | Unknown | Recovered | [3] |

| 4 | 62/M | 2011, Finland | Bacteraemia septic arthritis (in two joints) | DMII, | Horses | Cefuroxime (first three days), changed to IV vancomycin (unknown duration), changed to penicillin G with clindamycin (2 weeks), changed to oral cephalexin and clindamycin for 1 week | Sensitive to erythromycin, clindamycin, penicillin, vancomycin, and cephalexin | Unknown, but >3 weeks | Recovered | [1] |

| 5 | 70/M | 1985, England | Septic arthritis, sepsis, acute renal failure | AH, HD, osteo- and rheumatoid type arthropathy | No daily animal contact, possible ingested unpasteurised milk | IV penicillin G (3 week), oral penicillin (3 months) | Unknown | 3 months and 3 weeks | Recovered | [14] |

| 6 | 78/M | 2003–2015, Sweden | Sepsis, and septic arthritis | AH, HD, CLL | Unknown | 12 weeks and 8 days | Unknown | [15] | ||

| 7 | 71/M | 2003–2015, Sweden | Septic arthritis | WM | Unknown | Penicillin G followed by amoxicillin | Unknown | 17 weeks and 1 day | Unknown | [15] |

| 8 | 79/M | 2003–2015, Sweden | Septic arthritis | AH | Horses | Penicillin G followed by amoxicillin | Unknown | 17 weeks and 1 day | Unknown | [15] |

| 9 | 42/M | Unknown | Septic arthritis | None | Horses | Penicillin G | Unknown | Unknown | Recovered | [16] |

| 10 | 74/F | 1992, USA | Septic arthritis, bacteraemia | None | No relation to contact with animals | Penicillin changed to vancomycin due to suspicion of penicillin allergy | Unknown | 5 weeks | Recovered | [16] |

The table includes 10 of the 16 cases. The last six cases are not included because the information in the articles was either impossible to get access to or not detailed enough to fulfil the table: One case of purulent arthritis in the article “An outbreak of Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus associated with consumption of fresh goat cheese.” Three more cases are described in “Group C streptococcal bacteremia: analysis of 88 cases.” Finally, two cases from England presented in “Group C streptococci in human infection—a study of 308 isolates with clinical correlations.” AH: arterial hypertension; IHD: ischemic heart disease; HD: heart disease; DMII: diabetes mellitus type II; WM: Waldenströms macroglobulinemia; CLL: chronic lymphatic leukaemia; USA: the United States of America.

2. Case Presentation

An 82-year-old Caucasian male was admitted to our hospital in December 2016 with dyspnea, hemoptysis, and impaired general condition. He also presented with pseudoparalysis of his left shoulder due to severe pain. The medical record included ischemic heart disease (coronary artery bypass grafting in 1994), atrial fibrillation, low malignant prostate cancer, gout, and diabetes mellitus type II. Six months prior to admission, the patient had all teeth in his upper mouth removed prior to being fitted with dentures. This dental procedure was complicated with severe inflammation, and the patient was treated several times with oral antibiotics.

On admission, the patient was septic with fever and in a condition with pulmonary congestion and bilateral oedema in his lower limbs. Vital parameters included a blood pressure of 148/62 mmHg, a heart rate of 84 beats/min, oxygen saturation of 81% without oxygen supplementation, respiratory frequency at 26 per minute, and a rectal temperature of 38.8°C. Arterial blood gasses showed a normal pH (7.44), low partial pressure of carbon dioxide (3.5 kPa) and oxygen (7.2 kPa) in arterial blood, and low oxygen saturation (89%). On physical examination, the patient's left shoulder was tender and warm and had an anterior nonerythematous swelling. Cardiac auscultation did not reveal any murmur, and the neurologic examination was normal. The electrocardiogram revealed normofrequent atrial fibrillation and right bundle branch block.

The initial blood samples showed leucocytosis (14.7 × 109/L) with dominance of neutrophilic granulocytes, haemoglobin level of 7.1 mmol/L, and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 216 mg/L.

Chest X-ray showed no infiltrates but was consistent with pulmonary stasis. An X-ray of the left shoulder showed no signs of inflammation.

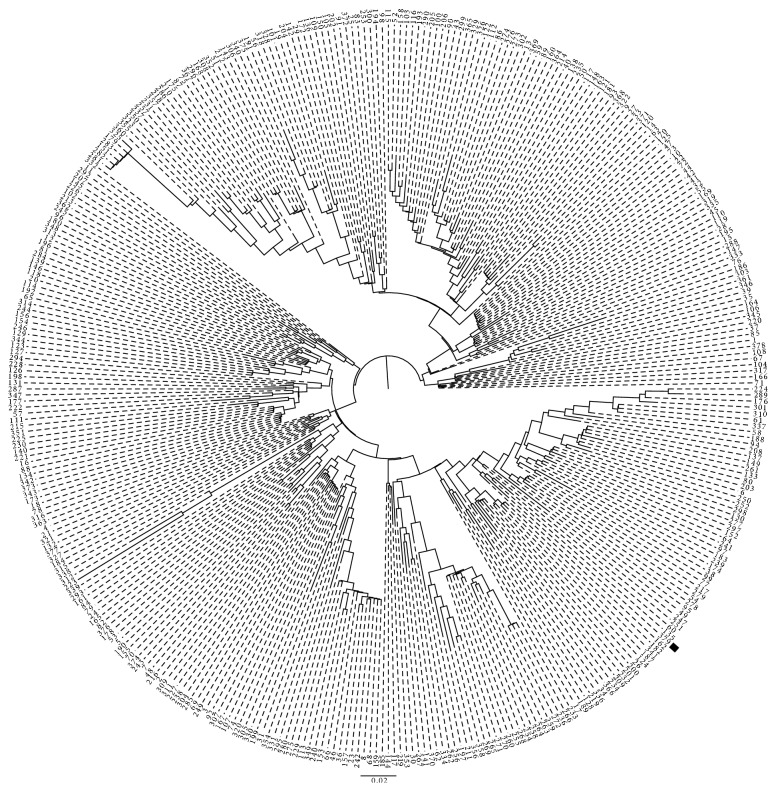

Blood cultures (three bottles with 10 ml each) and two samples of synovial fluids from the left shoulder were sent to the laboratory. Next day, growth of Gram-positive cocci was seen in one of the three blood culture bottles and in both synovial fluids. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) was performed on all three isolates using Microflex™ LT MALDI-TOF-System (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany; two databases: 1829023 Maldi Biotyper Compass Library and 8254705 Security ref. Library 1.0 for MALDI Biotyper 2.0), and they were diagnosed as S. equi subspecies zooepidemicus with a score between 2.37 and 2.63. Whole-genome sequencing of the blood culture isolate was performed by 251-bp paired-end sequencing (MiSeq; Illumina) and confirmed the species and subspecies type diagnosed by MALDI-TOF MS. The isolate carried a novel sequence type (ST379), and a phylogenetic analysis using FastTree v2.1.5 of the concatenated MLST alleles (Figure 1) found it to cluster in a branch containing ST60, ST135 and ST162. An analysis using the iTOL implementation at https://pubmlst.org/szooepidemicus/ revealed that seven related isolates with those ST types were reported in the database from various hosts (cow (n=1), dog (n=1), and horse (n=5)). The sequence data has been uploaded to ENA with the following Study and Read accession IDs: PRJEB24181 and ERR2233447, respectively. Antibiotic susceptibility testing using the Epsilometer test (E-test) (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) showed that the isolate was susceptible to penicillin (0.016 microgram/ml), ampicillin (0.032 microgram/ml), amoxicillin (0.047 microgram/ml), cefuroxime (0.016 microgram/ml), erythromycin (0.094 microgram/ml), clindamycin (0.38 microgram/ml), vancomycin (0.5 microgram/ml), imipenem (0.012 microgram/ml), and rifampicin (0.012 microgram/ml). The isolate was intermediate susceptible to gentamicin (12 microgram/ml).

Figure 1.

Relatedness of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. A midpoint-rooted phylogenetic analysis using a maximum likelihood-approximation of concatenated MLST allele for all publically available ST types, except ST's 248, 324 and 359 from which yqiL is partially lost. The location of ST379 is highlighted. The scale bar reflects genetic distance in expected number of nucleotide changes per site.

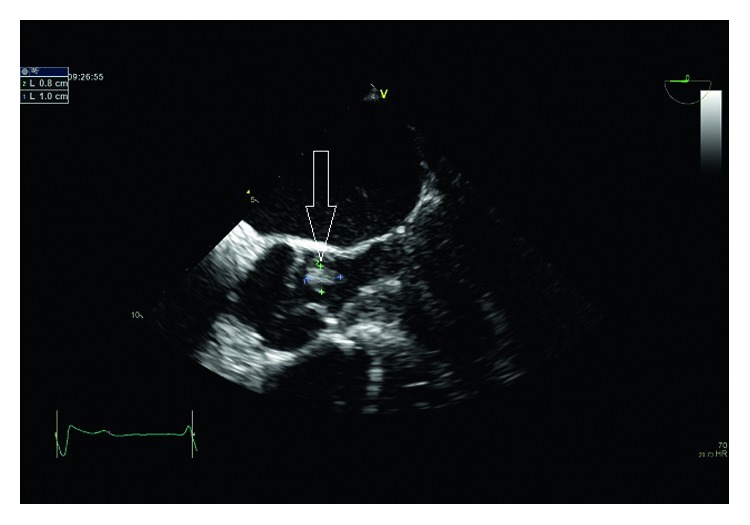

Antibiotic treatment the first two days was intravenous cefuroxime 1.5 gram administered three times daily, which was changed to intravenous high-dose benzylpenicillin, initially a dose of 2 million international units (IU) four times a day. The monotherapy with benzylpenicillin was supplemented with intravenous gentamicin in intervals (five days in total). On day three, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography (TTE and TEE, resp.) demonstrated a vegetation on the aortic valve (Figure 2) with a minimal aortic insufficiency. There were no signs of paravalvular abscesses and no stenosis of the affected valve. Ejection fraction was normal. The patient was diagnosed with aortic valve endocarditis without indication for acute operation. According to the national Danish guidelines for infective endocarditis, the benzylpenicillin dosage was increased to 5 million IU four times a day.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the patient's transesophageal echocardiography demonstrating the vegetation on the aortic valve by the white arrow.

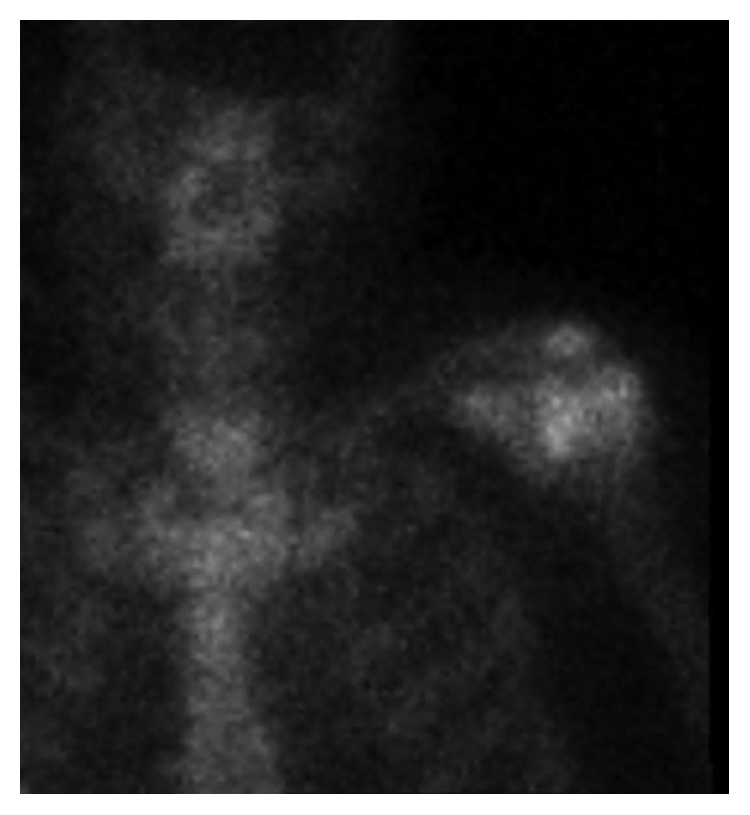

On day three, CRP levels were increasing as well as the pain and oedema in his left arm. On day five, arthroscopic revision of the left shoulder was performed and three biopsies were taken, but none of these cultures showed further growth of the pathogen. The rotator cuff was almost completely degenerated, and the humeral head was devoid of its hyaline cartilage. Ten days later technetium-99m bone scintigraphy showed intense activity in the left shoulder, suspicious of osteitis (Figure 3). The bone scintigraphy revealed no other focus of infection. On day 17, control transesophageal echocardiography was performed. At this time, the examination showed no suspicious signs of endocarditis, and the vegetation that was previously seen on the aortic valve could not be visualised.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the patient's left shoulder by Technetium-99m scintigraphy.

The patient was sent to a dentist, which did not reveal any oral focus. The patient's clinical condition improved gradually, and he was discharged from our hospital after five weeks (36 days) with oral antibiotics (oral amoxicillin 1 g × 3 pr. day and oral rifampicin 600 mg × 2 pr. day) for further two months. In total, he received antibiotics for almost three months (87 days). During the admission, the patient lost approximately 17 kilograms in weight, primarily fluid associated with his septic condition as well as fluid from some of degree cardiac decompensation and lung stasis.

The patient was followed up in the Out-Patient Clinics for Infectious Diseases and Cardiology, which included blood samples and control transthoracic echocardiography. None of the subsequent examinations indicated signs of recurrence. The patient regained normal function in his left shoulder.

The patient reported that he had daily contact with animals including horses, though he did not recall any illness in the four horses he had taken care of the past year. He denied consuming unpasteurized milk products.

3. Discussion

Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus is a zoonotic pathogen, and infections of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus in individual patients are associated with those having daily contact with animals, especially horses [1, 4, 15]. Human cases have been described with cutaneous and pulmonary entries as possible ways of transmission [13, 17], although the primary source of infection is mostly unknown, except for well-described outbreaks [3, 4, 15, 18, 19].

That the patient in the present report had infections and inflamed sores in his mouth months before admission, and concurrently had daily contact with horses, suggests the mouth as a possible entry for the zoonotic transmission. This assumption is given that the horses were infected with the bacteria, which is unknown. Therefore, it could have been interesting to obtain nasopharyngeal swabs form the horses in contact with the patient to explore the origin of infection. Even though the patient and his family denied any sign of illness from the horses, it is still possible they were infected or colonised carrier [20]. Pelkonen et al. describe three human cases of bacteraemia with S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus and identification of same bacteria in the horses, who were without any serious signs of illness [1].

The literature reveals 17 cases of endocarditis due to infection with S. zooepidemicus (Table 1). The Modified Duke Criteria are widely accepted for diagnostic classification of infective endocarditis (IE) [21, 22]. The diagnosis can be difficult to establish and is primarily based on blood cultures, echocardiographic findings, and clinical manifestations. In the present case, despite a strong clinical likelihood of aortic valve endocarditis based on a large mass that resolved with appropriate therapy, the patient did not meet the formal requirements for definite IE, which would be one major and three minor criteria. Given that the blood cultures were not repeated in the acute phase, bacteremia could not count as a major criterion. In addition, the rarity of S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus human infections assures that it is not considered “a typical microorganism consistent with endocarditis” which is required to constitute a major criterion. Our patient therefore fulfilled one major and two minor criteria, classifying this as a case of possible endocarditis according to the Modified Duke Criteria [21, 22]. Despite this, the patient was considered to have aortic valve endocarditis by the clinical team and was treated consistent with the presence of endocarditis, and the large mass consistent with valvular infection resolved on repeat high-resolution imaging.

An analysis from 1990 assessed the mortality rate to 40% based on six fatalities out of 15 patients [23]. Several studies have investigated a possible explanation causing a high mortality rate in affected humans with S. equi subsp. zooepidemicus [5, 9]. Salata et al. described in 1989 an increased susceptibility to disseminated infection among elderly with comorbidities, especially illnesses as chronic cardiopulmonary disease, arterial hypertension, and diabetes mellitus type II [24]. This assumption is well underpinned in the latest published data on outbreaks due to S. zooepidemicus [3, 18]. Additionally, published data indicate a better outcome if infected sporadically, rather than in clusters due to outbreaks [15].

Another important factor influencing the outcome is the choice of antibiotic treatment. Benzylpenicillin is preferred with bacteraemia caused by group C streptococci and can be supplemented with aminoglycoside leading to a successful result. Combining penicillins with aminoglycosides may have a positive effect of lowering the risk of needing valve replacement in the case of endocarditis [23]. In case of allergy to penicillin, previous studies have used ceftriaxone or levofloxacin combined with rifampin [4, 17, 18]. Previous studies have not found development of resistance to penicillin [3, 23].

Purulent arthritis has been described in 16 cases (Table 2). The arthroscopy was postponed to day 5 due to the patient's clinical and cardiovascular status. An arthroscopy must be conducted in a view of protecting the cartilage and is the favoured approach in treatment of purulent arthritis [25]. The results from Technetium-99m bone scintigraphy may be influenced by the surgery. A magnetic resonance imaging of the affected shoulder was not performed, although this investigation probably could give even more accurate results and affirm or debilitate the suspicious of osteitis.

4. Conclusion

This report highlights how virulent S. zooepidemicus can be when affecting humans. An 82-year-old man, who had daily contact with horses, developed a disseminated infection and was treated for sepsis, endocarditis, purulent arthritis, and osteitis. The patient responded well to the treatment, which primarily consisted of intravenous high dosage benzylpenicillin combined with gentamicin followed by oral amoxicillin and oral rifampicin. The patient recovered without permanent injuries.

It is recommended that identification of group C streptococci in humans is followed by determination of their species with the purpose of correct intervention, or in the event of an outbreak, limiting the spread of a pathogen associated with a high mortality rate. It is also of medical and epidemiological interest to identify group C streptococci at species level regarding the incidence of this virulent organism [1, 17]. In relation to invasive infection, patients in close contact with domestic animals or with a recent intake of unpasteurised dairy products, the pathogen S. zooepidemicus should be taken in consideration as a possible causation.

Consent

The patient gave written consent to publication of a case report on the 12th of December 2016.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pelkonen S., Lindahl S. B., Suomala P., et al. Transmission of Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus infection from horses to humans. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2013;19(7):1041–1048. doi: 10.3201/eid1907.121365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindahl S. Uppsala, Sweden: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Uppsala; 2013. Streptococcus equi subsp. equi and Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus-upper respiratory disease in horses and zoonotic transmission to humans. Ph.D. dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bordes-Benítez A., Sánchez-Oñoro M., Suárez-Bordón P., et al. Outbreak of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus infections on the island of Gran Canaria associated with the consumption of inadequately pasteurized cheese. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2006;25(4):242–246. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0119-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poulin M.-F., Boivin G. A case of disseminated infection caused by Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2009;20(2):59–61. doi: 10.1155/2009/538967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnham M., Kerby J., Chandler R. S., Millar M. R. Group C streptococci in human infection: a study of 308 isolates with clinical correlations. Epidemiology and Infection. 1989;102(3):379–390. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villamil I., Serrano M., Prieto E. Streptococcus equi subsp. Zooepidemicus endocarditis. Revista Chilena de Infectología. 2015;32(2):240–241. doi: 10.4067/s0716-10182015000300017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daubié A. S., Defrance C., Renvoisé A., et al. Illustration of the difficulty of identifying Streptococcus equi strains at the subspecies level through a case of endocarditis in an immunocompetent man. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014;52(2):688–691. doi: 10.1128/jcm.01447-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eyre D. W., Kenkre J. S., Bowler I. C. J. W., McBride S. J. Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus meningitis-a case report and review of the literature. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2010;29(12):1459–1463. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuen K. Y., Seto W. H., Choi C. H., Ng W., Ho S. W., Chau P. Y. Streptococcus zooepidemicus (Lancefield group C) septicaemia in Hong Kong. Journal of Infection. 1990;21(3):241–250. doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(90)93885-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinez-Luengas F., Inclan G. M., Pastor A., et al. Endocarditis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1982;127(1):p. 13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards A. T., Roulson M., Ironside M. J. A milk-borne outbreak of serious infection due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus (Lancefield Group C) Epidemiology and Infection. 1988;101(1):43–51. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800029204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghoneim A. T., Cooke E. M. Serious infection caused by group C streptococci. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1980;33(2):188–190. doi: 10.1136/jcp.33.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friederichs J., Hungerer S., Werle R., Militz M., Bühren V. Human bacterial arthritis caused by Streptococcus zooepidemicus: report of a case. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;14(S3):e233–e235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnham M., Ljunggren A., Mcintyre M. Human infection with Streptococcus zooepidemicus (Lancefield group C): three case reports. Epidemiology and Infection. 1987;98(2):183–190. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800061896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trell K., Nilson B., Petersson A. C., Rasmussen M. Clinical and microbiological features of bacteremia with Streptococcus equi. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2017;87(2):196–198. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collazos J., Echevarria M. J., Ayarza R., de Miguel J. Streptococcus zooepidemicus septic arthritis: case report and review of group C streptococcal arthritis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1992;15(4):744–746. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.4.744-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhatia R., Bhanot N. Spondylodiskitis secondary to Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus. American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2012;343(1):94–97. doi: 10.1097/maj.0b013e31822cf8a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuusi M., Lahti E., Virolainen A., et al. An outbreak of Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus associated with consumption of fresh goat cheesez. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:p. 36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sesso R., Wyton S., Pinto W. L. Epidemic glomerulonephritis due to Streptococcus zooepidemicus in Nova Serrana, Brazil. Kidney International. 2005;68(97):S132–S136. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.09722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waller A. S. Strangles: taking steps towards eradication. Veterinary Microbiology. 2013;167(1-2):50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li J. S., Sexton D. J., Mick N., et al. Proposed modifications to the duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1984;30(4):633–638. doi: 10.1086/313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baddour L. M., Wilson W. R., Bayer A. S., et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications. Circulation. 2015;132(15):1435–1486. doi: 10.1161/cir.0000000000000296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley S. F., Gordon J. J., Baumgartner D. D., et al. Group C streptococcal bacteremia: analysis of 88 cases. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1991;13(2):270–280. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salata R. A., Lerner P. I., Shlaes D. M., Gopalakrishna K. V., Wolinsky E., Wolinsky E. Infections due to Lancefield group C streptococci. Medicine. 1989;68(4):225–239. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198907000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peres L. R., Marchitto R. O., Pereira G. S., Yoshino F. S., Fernandes M. D. C., Matsumoto M. H. Arthrotomy versus arthroscopy in the treatment of septic arthritis of the knee in adults: a randomized clinical trial. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2016;24(10):3155–3162. doi: 10.1007/s00167-015-3918-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]