Abstract

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) continues to have adverse effects on cognition and the brain in many infected people, despite a reduced incidence of HIV-associated dementia with combined anti-retroviral therapy (cART). Working memory is often affected, along with attention, executive control, and cognitive processing speed. Verbal working memory (VWM) requires the interaction of each of the cognitive component processes along with a phonological loop for verbal repetition and rehearsal. HIV-related functional brain response abnormalities during VWM are evident in functional MRI (fMRI), though the neural substrate underlying these neurocognitive deficits is not well understood. The current study addressed this by comparing 24 HIV+ to 27 demographically matched HIV-seronegative (HIV−) adults with respect to fMRI activation on a VWM paradigm (n-back) relative to performance on two standardized tests of executive control, attention and processing speed (Stroop and Trail Making A–B). As expected, the HIV+ group had deficits on these neurocognitive tests compared to HIV− controls, and also differed in neural response on fMRI relative to neuropsychological performance. Reduced activation in VWM task-related brain regions on the 2-back was associated with Stroop Interference deficits in HIV+, but not with either Trail Making A or B performance. Activation of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) of the default mode network during rest was associated with HVLT-2 learning in HIV+. These effects were not observed in the HIV-controls. Reduced dynamic range of neural response was also evident in HIV+ adults when activation on the 2-back condition was compared to the extent of activation of the default mode network during periods of rest. Neural dynamic range was associated with both Stroop and HVLT-2 performance. These findings provide evidence that HIV-associated alterations in neural activation induced by VWM demands and during rest differentially predict executive -attention and verbal learning deficits. That the Stroop, but not Trail-Making was associated with VWM activation suggests that attentional regulation difficulties in suppressing interference and/or conflict regulation are a component of working memory deficits in HIV+ adults. Alterations in neural dynamic range may be a useful index of the impact of HIV on functional brain response, and as a fMRI metric in predicting cognitive outcomes.

Keywords: HIV, working memory, functional MRI, attention, executive control, Stroop

There have been dramatic improvements in mortality and morbidity rates among people infected with HIV, including marked reductions in HIV-associated dementia since combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) became widely available two decades ago1,2. Initial hope that brain disorders caused by HIV would be largely eradicated was unfortunately tempered by continuing reports of milder forms of HIV-associated neurocognitive dysfunction in many infected adults3. The current prevalence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) is approximately 50%4–8. As in the pre-cART era, cognitive processing speed and executive, attention, and working memory functions remain affected4,6,7,9–11. For example, reduced performance on the Stroop Color-Word Interference Test (Stroop) was described in pre-cART era studies12, and continues to be observed. Slowing and reduced information processing efficiency was also evident in early studies of HIV13–16, and still remains a common finding.

Brain abnormalities resulting either directly from infection of the central nervous system or indirectly from secondary immunological and neuroinflammatory responses to the virus are thought to be responsible for cognitive disturbances in HIV+ people17–19. Subcortical areas, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and corpus callosum are vulnerable to structural and metabolic changes from HIV20–26. However, reduced cortical volumes are also evident when HIV+ adults are compared to HIV-seronegative controls23,27–32. Frontal, parietal, and global cerebral gray and white matter may be affected30,31,33,34. Structural abnormalities of white matter integrity are also evident on diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)35–43, with disruption of frontal-subcortical pathways44–47. Increased quantities of white matter hyperintensities on MRI in HIV+ adults is indicative of frank structural damage, with these white matter lesions contributing to slowing and cognitive inefficiency46,48–51.

Cerebral metabolic disturbances on magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) provide evidence of pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the structural brain abnormalities and cognitive disturbances in HIV. Abnormal concentrations of particular cerebral metabolites have been linked with various metrics of HIV clinical status, including current and past immune function (current and nadir CD4), viral load (HIV RNA), duration of infection, as well as various co-morbidities11,27,52–54. Cerebral metabolic disturbances evident in the gray and white matter of the frontal cortex and the basal ganglia of HIV+ adults have also been associated with cognitive deficits55–57.

Fewer studies have focused on HIV-associated functional brain abnormalities, though fMRI findings to date provide evidence of fMRI abnormalities. Cerebral hemodynamic abnormalities were found in the pre-cART era58, though most functional neuroimaging studies of HIV were conducted over the past decade. Overall, these studies indicate inefficient neural activation during cognitive processing and also during rest among HIV+ adults with one study showing that fMRI abnormalities were associated with cerebral metabolite abnormalities on MRS59. Reduced activation across cortical attention networks have been found to be associated with increased activation elsewhere in the brain during attention network tasks60,61. HIV+ adults exhibited increased parietal activation during easy working memory tasks and increased frontal activation during difficult working memory tasks59,62. However, HIV+ adults also showed smaller differences in working memory load-dependent activation between easy and difficult tasks. Ernst and his colleagues attributed this effect to neural inefficiency61, possibly associated with reduced cognitive reserve secondary to HIV63.

In an earlier study, Tomasi et al. showed that acoustic noise presented during working memory performance reduced fMRI activation in frontal and parietal brain areas. Effects were greatest among HIV+ adults, which was attributed to a reduction in neural “dynamic range” caused by competition from the acoustic noise that interfered with cognitive performance63. By inference, neural dynamic range was a function of HIV-associated cognitive capacity limitations caused by HIV. That study introduced the concept of neural dynamic range to explain the impact of HIV on brain function, but did not operationalize the construct itself.

To further examine the effects of HIV on neural response of brain systems involved in working memory, we previously compared HIV+ and HIV− participants in a longitudinal study of aging effects on HIV-associated cognitive and brain dysfunction. fMRI activation was assessed during an n-back paradigm64, and HIV was associated with a reduced range of task-related fMRI activation64. There was a reduction in neural dynamic range when 2-back activation was compared to activation on the 0-back and rest conditions. Consistent with past fMRI findings65, HIV+ adults also had increased variability of neural response which was found to be associated with HIV-associated clinical factors, including cART treatment, its effectiveness in reducing viral load, and the presence of co-morbidities contributed to variability in functional brain response64,66–68. Importantly, many of these factors are also associated with cognitive impairment severity. Detectable viral load9, current and nadir CD469, time since HIV diagnosis70, early detection of the virus71 the presence of certain co-morbid conditions9,72 have all been linked to HIV-associated cognitive dysfunction. For the most part, HIV no longer causes severe focal brain abnormalities or dementia as it did in the early years of the AIDS epidemic1,3,73, and many of the clinical factors that may underlie increased variability of neural dysregulation on fMRI also contribute to neurocognitive dysfunction in HIV+ individuals4,9,74.

In sum, reductions in both cognitive and neural efficiency on fMRI occur among HIV+ adults, which may result in diminished cognitive and/or neural reserve attributable to infection with HIV and associated clinical factors. The fact that working memory, attention and executive functions are affected in about 50% of HIV+ adults points to the need for functional neuroimaging studies that may increase understanding of the neural bases of impairments in these cognitive domains. Activation of the Default Mode Network (DMN) has been shown to vary as a function of episodic learning and memory75. Furthermore, patients with other neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease) have been shown to demonstrate abnormalities on fMRI as it relates to their verbal learning and memory performance. Specifically, abnormal activation of the brain regions associated with the DMN such as the Posterior Cingulate Cortex has been implicated as a potential contributor to the amnestic disturbance in this population76,77. Typically, fMRI studies have examined the relationship between activation of task-associated brain regions and performance on the cognitive tasks that are eliciting the activation. Yet, the correspondence between fMRI activation during tasks requiring specific cognitive functions, such as VWM, and performance on neuropsychological tests that are standardized and commonly used to clinically assess HIV-associated neurocognitive dysfunction has not yet been determined. Determining a relationship between the neural dynamic range associated with on- and off-task brain activation and performance on common standardized neuropsychological measures may serve to extend our previous longitudinal work by providing an easily identified biomarker for HIV-related cognitive dysfunction. From a translational perspective, neuropsychological test performance might then be utilized to predict neural efficiency using the aforementioned biomarker.

Accordingly, the current study was conducted to determine whether fMRI brain activation occurring during a VWM paradigm (n-back) was predictive of performance on neuropsychological tests (Stroop, Trail Making Test A& B) commonly used to assess HIV-associated attention, executive control, and processing speed deficits. Specifically, we hypothesized that increased prefrontal cortical activation occurring during the 2-back VWM task would correspond with performance deficits on the interference condition of the Stroop test and to a lesser extent on Trail-Making Test B. Besides requiring focused and sustained attention, executive control, and adequate processing speed, these two tests place demands on the working memory system. We also hypothesized that activation during the 0-back condition relative to rest in HIV+ adults would be predictive of performance on Trail-Making Test A, a task that primarily requires attention and rapid processing speed. A reduced dynamic range of neural response in task-related brain regions was also hypothesized such that reduced dynamic range would be predictive of performance deficits among HIV+ adults on the Stroop and Trail Making Test B. In this context dynamic range was operationalized as the difference between the mean intensity of activation in five brain regions that are part of the VWM system during the 2-back task and activation of the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) within the default mode network during 0-back performance.

METHODS

Participants

The study sample consisted of 51 adults (24 HIV+ and 27 HIV-seronegative) from a large cohort of 184 adults recruited from The Miriam Hospital Immunology Center as part of an NIH-sponsored study of HIV-associated brain dysfunction (R01M074368). These 51 participants were selected based on their willingness to undergo functional neuroimaging in addition to the standard assessments. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards for the Miriam Hospital and Brown University and informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment. From this cohort, fMRI on the VWM paradigm was acquired from 85 participants. fMRI neuroimaging was not an original specific aim of the project, but was added as a supplemental procedure for this subset of the cohort who met inclusion / exclusion criteria and also were willing to have additional neuroimaging.

Eight HIV+ participants were excluded because they had hepatitis C (HCV) co-infection. The rationale for this exclusion was to avoid confounding due to this comorbidity that affects cognition in its own right. Ten participants were excluded due to either failure to complete the n-back task as instructed or because their performance below the threshold of 75% correct responses. Two participants were excluded due to scanner artifacts that prevented adequate image registration. Ten participants were excluded for excessive head motion, while four were excluded due to a combination of performance issues and excessive head motion. After these exclusions, the sample size for the analyses in the current study consisted of 24 HIV+ and 27 HIV-seronegative, 22 of which were females (43%). Statistical comparison did not reveal significant differences in key demographic variables (i.e. age, education, race, gender, lifetime substance dependence, disease-related clinical characteristics) between the resulting 51-person sample and the larger 184-person cohort originally described by our group9. See Table 1 for participant demographic and clinical information.

Table 1.

Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Study Sample: HIV+ and HIV−

| Demographics | Full Sample (n=51) |

HIV+ (n=24) |

HIV− (n=27) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.6 (10.8) | 45.9 (9.6) | 45.3 (11.9) |

| Education (years) | 13.7(2.8) | 13.3 (2.0) | 14.0 (3.4) |

| Proportion male (%) | 55 | 58 | 52 |

| Proportion Caucasian (%) | 76 | 75 | 68 |

| Clinical HIV Measures | |||

| Duration of HIV infection | N/A | 13.3 (2.1) | N/A |

| CD4 nadir (cells/l) | N/A | 210.7 | N/A |

| Current CD4 (cells/l) | N/A | 562.8 | N/A |

| Undetectable Viral Load (%) | N/A | 75 | N/A |

| Proportion on HAART (%) | N/A | 86 | N/A |

| Substance Abuse | |||

| Alcohol Dependence | 6/24 | 3/11 | 3/13 |

| KMSK Alcohol Sum | 8.73 (3.9) | 9.04 (4.2) | 8.44 (3.7) |

| Cocaine Dependence | 0/18 | 0/11 | 0/7 |

| KMSK Cocaine Sum | 4.57 (6.0) | 5.83 (6.4) | 3.44 (5.6) |

| Narcotic Dependence | 0/9 | 0/6 | 0/3 |

| KMSK Narcotic Sum | 0.47 (1.9) | 0.29 (0.8) | 0.63 (2.5) |

Note: Means and standard deviations are shown for the full combined sample, and for the HIV+ and HIV− groups.

Bolded values indicate significant sex-based differences exist.

Neuropsychological Measures

Participants were administered well-established standardized neuropsychological tests for which there is extensive normative data78,79: the Trail-Making Test (Parts A & B)80, the Stroop Color Word Interference Test (Stroop)81, and the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT)82. These tests have been widely used in past studies of HIV83 research, including our studies of HIV9, and are used for the assessment and classification of HAND74,84. The Trail-Making and Stroop tests are generally considered to be tests of executive function and are also sensitive to attentional and processing speed deficits. Total elapsed time to completion for the Trail-Making Test was recorded and a demographically-corrected T-score was obtained as the comparison variable of interest for this measure using established norms80. Similarly, the interference score on the Stroop Test was calculated and demographically-corrected T-scores were obtained using established normative data78. The HVLT-R provides measures of verbal learning across trials and delayed recall, best represented by total learning across the three learning trials and the delayed memory score, which were the measures of interest in the present study. As such, the demographically-based T-score for total learning and delayed memory scores on the HVLT were obtained using established norms for statistical comparison79. All variables of interest met normality requirements based on the assumptions of the GLM with the exception of Trail-Making Test Part A, which was mildly kurtotic due to many participants obtaining a similar performance – a relatively common finding in studies utilizing this task.

Self-Report Measures

Participants provided self-reported responses to questions regarding the duration, frequency, and quantity of use for common substances of abuse on the Kreek-McHugh-Schluger-Kellogg scale85. Additionally, a structured interview was employed to determine the presence or absence of substance dependence for alcohol, cocaine, and opiates.

N-Back Paradigm

A n-back paradigm was employed in conjunction with fMRI imaging that consisted of alternating periods during which participants performed either a VWM tasks (2-back) or an attentional task requiring vigilance (0-back), with an alternating rest interval. This n-back paradigm has been used by our group in a number of studies as previously described64 (Supplemental Figure 1). The task sequence consisted of eight 45-s 2-back blocks (15 consonants each) and eight 30-s 0-back blocks (nine consonants each). Blocks were presented in an alternating pattern (Rest/Fixation; 0-back; 2-back). Data was acquired in two separate task runs, each 6.125 minutes in duration. Participants responded with two fingers making a binary button press on two response keys by which they indicated whether or not letter stimuli had occurred previously either 0- or 2-stimuli before in the presentation sequence yielding performance data as described below. Performance on the 0-back and 2-back tasks was indexed as correct target detections (hits) and foil rejections, discrimination accuracy (A’ = Z hits – Z false positive errors) and response time (mean and variability).

Statistical Analysis

Nonparametric Mann-Whitney or Kruskall-Wallis tests were used to compare the HIV-seropositive (HIV+) and HIV-seronegative (HIV−) participants on demographic and ordinal clinical indices, while t-tests were used to compare groups on clinical indices having continuous interval or ratio data. The performance of HIV+ and HIV− participants was compared on measures derived from neuropsychological testing and the n-back fMRI tasks (0- and 2-back). Statistical analyses of the neuroimaging data were conducted using general linear modeling (GLM) as described in the description of fMRI analyses below, including analyses in which activation and deactivation of significant clusters for each comparison of task conditions was regressed onto the neuropsychological performance measures for the HIV+ and HIV− groups.

FMRI Data Acquisition

Whole-brain, echoplanar BOLD FMRI images were acquired in 42 interleaved axial 3mm slices (TR=2500ms, volumes=147, TE=28ms, FOV=1922mm, Matrix=642) on a Siemens 3 Tesla TRIM TRIO magnet (Siemens Corporation, 2013).

FMRI Analysis

Image pre- and post-processing and statistical analysis were conducted using Statistical Parametric Mapping-5 (SPM-5: Wellcome, London, UK: http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) implemented in MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Sherborn, MA, USA). Preprocessing steps included head motion correction, normalization EPI image using default SPM parameters, and smoothing using a 6 mm FWHM isotropic Gaussian kernel. Realignment was done relative to the mean image volume using the default unwarp and realign function to account for susceptibility-movement interactions in orbitofrontal regions. Co-registration with the high-resolution T1 anatomical image was performed before the mean realigned and un-warped images were normalized to the Echo Planar Image (EPI) of the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) brain atlas. Smoothing was done with a Gaussian filter of 6 mm full width at half maximum (FWHM). Modeling of regressors of interest for each experimental condition, the instruction display and fixation epochs were defined and convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF). All models included a high-pass filter with a cut-off at 128s to remove scanner drifts.

Individual subject analysis

All experimental conditions were modeled in a block design at the subject level for statistical analysis of effects for comparison of task conditions. After reconstruction, functional data from each task run for each subject were entered into separate contrasts of interest at the run level. These contrasts were performed using activation data from each voxel during the rest periods, 0-back and 2-back trials. Second-level GLMs were conducted to generate 2-back vs. rest, 0-back vs. rest and 2-back vs. 0-back contrasts. The resulting set of voxel values for the assessed contrasts constituted the associated SPM of the t-statistics (SPM<T>) with a threshold of p < .001 for the maximum voxel intensity and an extent threshold k = 8 voxels. Resulting clusters of activation and deactivation for each were considered statistically significant at cluster-level p<0.05, corrected for the entire brain volume (FDR-corrected). To provide optimal insight in the coherent data set obtained from the various conditions, the results are displayed at p<0.001 voxel-level significance in the figures, while the corresponding cluster-level corrected activations are reported in the tables. Data passing quality control thresholds were passed on to second-level, fixed-effects GLMs averaging within subject across runs using the T-scores for significantly activated and deactivated clusters based on the differences between conditions (i.e., 0-back > rest; 2-back>rest; 2back > 0-back).

Group analysis

Second-level group analysis employed, a permutation-based method for GLM analysis. GLMs were run, modeling 0-back>rest, 2-back>0-back, and 2-back > rest, respectively. Within each GLM, contrasts of interest were main effects for each group (positive and negative activations for the HIV+ and HIV-seronegative groups) and direct comparisons among the diagnostic groups. Significant clusters for each cluster associated with a priori brain areas that are well established components of the VWM network and also attention and executive control were averaged across the voxels within the ROIs. ROIs included the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), bilateral inferior parietal lobe (IPL), and bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).

FMRI and Neuropsychological Test Performance

To characterize the association between activation of the VWM network and neuropsychological test performance, the mean of activation for the five brain ROIs were derived. The mean VWM activation and also DMN deactivation in the PCC during 2-back relative to rest and also relative to 0-back was then correlated with performance on the five neuropsychological test variables (Stroop, Trail-Making A-B, HVLT-Total Learning, HVLT-Delayed Recall). These correlation analyses were conducted for the HIV+ and HIV− groups separately. Correlation analyses were also conducted to examine the association between these same fMRI conditions and n-back task performance.

Dynamic Range Analysis

Based on previous findings indicating reduced dynamic range of fMRI activation across tasks and rest periods among HIV+ adults, measures were created for each participant to quantify this effect. In this context, dynamic range was conceptualized as a function of the difference in BOLD activation between the executive control network and default mode network was measured and termed as the dynamic range. The PCC was chosen as DMN measure for this analysis. Each subject’s dynamic range metric (DRM) was also correlated with neuropsychological test and N-Back performance measures.

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

HIV+ and HIV− participants did not differ with respect to age, education, or race. These groups also did not differ on current or lifetime alcohol, hallucinogen, inhalant, tranquilizer dependence or current cocaine or opiate dependence. Significant group differences did exist for endorsement of lifetime dependence for cocaine (χ2 = 10.143, p = 0.01), opiates (χ2 = 22.463, p < 0.001), and marijuana (χ2 = 12.933, p < 0.01), however groups did not differ significantly on self-reported frequency, quantity, and duration of lifetime substance abuse of alcohol, cocaine, or narcotics on the KMSK sum score. A higher proportion of the HIV+ participants had used these drugs in the past, but not for one year prior to the study, nor did any currently meet substance dependence diagnostic criteria.

Current CD4 value, nadir CD4, current viral load detectability and current cART treatment, and time since diagnosis are also shown for the HIV+ group. No HIV− participant tested positive on Elisa for either HIV or HCV infection. The clinical characteristics of the HIV+ group indicates that they had a relatively long duration of infection based on when HIV was first diagnosed (> 1 years). Analysis of nadir CD4 for HIV+ participants indicated that 52% met criteria for AIDS based on their CD4 count dropping to < 200 at some point in their disease course. All HIV+ participants had a nadir CD4 < 400, which was well below their current CD4 (t = 3.24, p < .01). Most HIV+ participants also had undetectable HIV RNA viral loads levels (75%), which was likely due to the high proportion of cART treated HIV+ participants (88%).

Neuropsychological Test Performance

There were significant differences in neuropsychological performance between the HIV+ and HIV− groups on the Stroop and HVLT Total Learning measures. Groups did not differ in their performance on the Trail-Making A or B tests. The between-group comparison of HVLT Delayed Recall performance approached statistical significance (p = .06). Summary statistics for these measures are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Neuropsychological Performance: HIV+ vs HIV−

| Measure | Full Sample | HIV+ | HIV− |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Stroop* | 37.1 (10.4) | 33.3 (9.5) | 40.4 (10.1) |

|

|

|||

| Trails A | 49.9 (9.6) | 50.2 (9.6) | 49.4 (9.6) |

|

|

|||

| Trails B | 49.7 (11.3) | 48.8 (10.3) | 50.6 (10.4) |

| HVLT-Memory* | 48.7 (12.1) | 45.6 (13.5) | 51.5 (11.8) |

|

|

|||

| HVLT-Learning* | 48.9 (11.6) | 45.3 (11.0) | 52.1 (12.1) |

|

|

|||

Note: Means and standard deviations of the demographically-corrected T-scores for each of the five neuropsychological measures are shown for the full combined sample, and for the HIV+ and HIV− groups.

indicates statistically significant between group difference (p <.05).

Bolded values indicate a sex-based difference in performance (p < .05).

N-Back Task Performance

The HIV+ and HIV− participants showed significant between-group differences on both n-back tasks. HIV+ participants had weaker performance on the both detection accuracy (A’) and reaction time for both the 0-back and 2-back tasks. The groups did not significantly differ in reaction time variability (See Table 2). While between-group differences existed on the n-back performance measures, HIV+ and HIV− participants both showed very high accuracy on the 0-back task. While 2-back performance was weaker in both groups reflecting the greater difficulty of this task, both groups performed well above chance, and the absolute magnitude of differences in accuracy and reaction time between HIV+ and HIV− participants was not large. Neither group had marked deficits on these tasks, and while differences were statistically significant, they likely have little clinical significance.

FMRI Activation

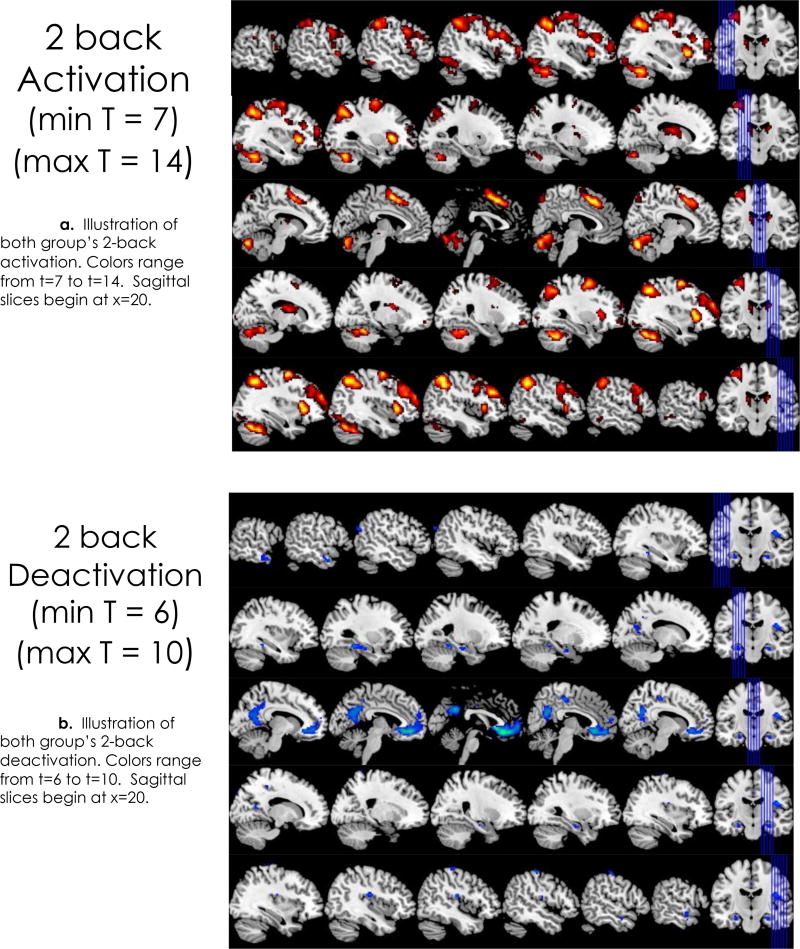

Significant activation was evident in all five a priori brain regions for the 2-back > 0-back and the 2-back > rest conditions. Conversely, significant deactivation in the PCC and other cortical areas that are part of the DMN was evident (rest > 2-back), which in effect indicates DMN activation of these areas during rest relative to 2-back activation (see Figure 1). The MNI coordinates and maximum activation (t-max) of these five cortical areas relative to 2-back and rest are given in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Brain regions with significant activation (2a: 7 < t < 14) and deactivation (2b: 6 < t < 10) for the 2-back > rest comparisons from group level analyses (sequential sagittal slices). Deactivations are the equivalent of activation when the analysis is inverted and rest is the condition of interest (rest > 2-back).

Table 3.

Performance on the 0-back and 2-back tasks: HIV+ and HIV−

| Measure | Full Sample (n=51) |

HIV+ (n=24) |

HIV− (n=27) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-Back Accuracy (%) | 97 (3.1) | 96 (4.1) | 98 (1.5) | 0.03 |

| 0-Back Hit Rate (%) | 96 (4.8) | 95 (5.9) | 98 (3.1) | 0.03 |

| 0-Back Response Time (ms) | 623.2 (147.6) | 665.7 (144) | 585.5 (143) | 0.05 |

| 2-Back Accuracy (%) | 78 (10.9) | 74 (11.6) | 81 (9.1) | 0.01 |

| 2-Back Hit Rate (%) | 72 (19.6) | 66 (23.8) | 78 (13.3) | 0.03 |

| 2-Back Response Time (ms) | 938.7 (295.2) | 1050.7 (277.1) | 839.1 (278.9) | 0.01 |

HIV Status and Functional Brain Response

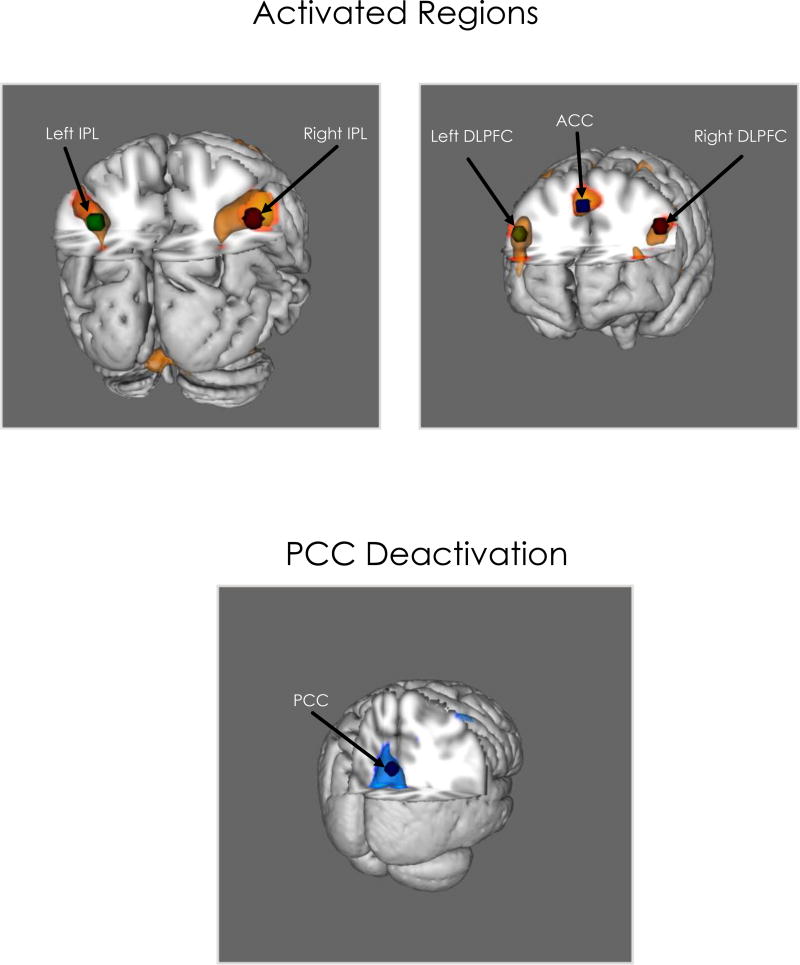

Both the HIV+ and HIV− groups showed bilateral activation in DLPFC, IPL, and ACC for 2-back > 0 –back and 2-back > rest. Both groups also showed deactivation of the PCC for rest > 0-back and rest > 2-back. Activation for the 0-back task was observed for both groups in left motor cortex and parietal regions and bilateral supplementary motor area, frontal, occipital, and cerebellar regions (see Table 4). Areas of significant activation and deactivation for the 2-back are shown below (Figures 1 & 2). Independent samples t-test revealed no significant difference in VWM activation between HIV− and HIV+ groups.

Table 4.

Brain Regions of Interest with Significant fMRI Response: 2-Back vs. Rest Group Contrasts

| Primary Regions | Activation (Max-T) | MNI Coordinates |

|---|---|---|

| Activation | ||

| ACC | 12.84 | 3, 24, 45 |

| Left DLPFC | 10.34 | −45, 24, 30 |

| Right DLPFC | 12.56 | 45, 30, 30 |

| Left IPL | 13.17 | −33, −60, 45 |

| Right IPL | 13.36 | 45, −48, 42 |

| Deactivation | ||

| PCC | 9.05 | 0, −51, 30 |

Note: Coordinates are provided for the a priori brain regions of interest. ACC = Anterior Cingulate Cortex; PCC = Posterior Cingulate Cortex; DLPFC = Dorsolateral Pre-Frontal Cortex; IPL = Inferior Parietal Lobule. Activations across the five ROIs were used to compute the mean activation of the VWM network for 2-back > rest, and the max T-value at the group level was extracted. The PCC was used as a proxy for DMN activation for rest > 2-back. This appeared as an area of significant deactivation on the 2-back > rest comparison. These two values were subtracted from each other to calculate the Dynamic Range index.

Bolded values indicate a significant sex-based difference in activation.

Figure 2.

Brain regions with significant activation and deactivation on the 2-back > rest comparisons (6 < t < 10) from group level analysis, visualized 3-dimentionally. ACC = Anterior Cingulate Cortex; PCC = Posterior Cingulate Cortex; DLPFC = Dorsolateral Pre-Frontal Cortex; IPL = Inferior Parietal Lobule

N-Back Activation and Neuropsychological Performance

fMRI response (activations and deactivations) was predictive of neuropsychological test performance, though observed relationships varied as a function of fMRI condition, neuropsychological test, and also HIV status (see Table 5). Activation of VWM network (2-back > rest) was significantly associated with Stroop performance in the HIV+ group (p < .05), but not with performance on the Trail-Making A or B, or the HVLT learning and memory measures. In contrast, PCC deactivation was significantly associated with HVLT-Total Learning, with this correlation approaching significance relative to HVLT-Delayed Recall (p < .10). PCC deactivation was not associated with either Stroop or Trail Making performance, but was associated with HVLT-Total Learning. Analysis of 2-back relative to 0-back activation showed an association with Stroop performance (p < .05), but not with the other neuropsychological measures. In contrast to the findings for the HIV+ group, no significant associations were found between the fMRI indices and any of the neuropsychological test measures in HIV-seronegative participants.

Table 5.

FMRI Associations with Neuropsychological Performance

| Group fMRI Contrast | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV+ | Stroop | Trails-A | Trails-B | Learning | Memory |

| 2 back Activation | 0 .47* | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.19 |

| 2 back Deactivation | −0.19 | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.45* | −0.31 |

| 2 back vs 0 back | 0.58** | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.30 |

| Dynamic Range | 0.41* | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.47* | 0.31 |

| HIV− | |||||

| 2 back Activation | 0.04 | −0.27 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.09 |

| 2 back Deactivation | −0.25 | −0.42* | −0.23 | −0.21 | −0.34* |

| 2 back vs 0 back | 0.27 | −0.18 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.12 |

| Dynamic Range | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

Note: The values presented in the table indicate the proportion of variance for each neuropsychological measure accounted for by each of the fMRI indices (r2) based on correlation analyses (*: p < .05; **: p < .01).

Bolded r2 values indicate a significant difference (p < .05) in the correlations between groups as indicated by a one-tailed Fisher’s r-to-z transformation. Dynamic range was computed as described in the Methods by subtracting T-max for PCC activation from the T-Max of the VWM network (derived as the mean of the five a priori ROI activated during the 2-back).

Dynamic Range and Cognitive Performance

Significant associations were found between the dynamic range metric (DRM) and both Stroop and HVLT-Total Learning performance in the HIV+ group (p < .05). The correlation between DRM and HVLT-Delayed Recall approached significance (p = .10). DRM was not associated with TMT performance. For the HIV-seronegative group, dynamic range of the functional brain response during 2-back VWM performance relative to rest did not correlate significantly with any of the neuropsychological tests.

DISCUSSION

Functional activation of VWM-related brain areas was found to be associated with neuropsychological performance assessed outside of the scanner at a different, though proximal point in time. Specifically, neural activation of the VWM network in HIV+ adults was positively associated with Stroop performance, but not with Trail-Making performance. HIV+ adults with greater activation in task-related brain regions had stronger Stroop performance – an effect which was evident during the 2-back condition relative to the 0-back condition and also rest, suggesting that this relationship between fMRI response and cognitive performance was robust in the context of HIV. This relationship between functional brain response and cognitive performance was not found for the HIV-seronegative group.

An entirely different effect was found for the relationship between cognitive performance and neural activation during the rest periods relative to the 2-back condition. Greater activation of the PCC during rest (i.e., deactivation on 2-back > rest comparison) was associated with stronger performance on the HVLT in the HIV+ group. PCC activation strongly correlated with HVLT-Total Learning, and approached significance for HVLT-Delayed Recall. In contrast, PCC activation was not associated with either Stroop or Trail-Making performance. The PCC is a component of the DMN that is usually activated when the entire network is responsive during rest or off-task periods. For this reason, it was used as a proxy for the response of the entire DMN to minimize the number of brain ROIs subject to analysis. As was the case for the ROIs activated during the 2-back task, neural activation during rest periods was not associated with neuropsychological test performance in the HIV-seronegative group. PCC activation was associated with verbal learning performance in HIV+ adults, but not among participants without HIV.

The relationship between neural activation on fMRI and neuropsychological performance varied as a function of HIV status, fMRI task condition, the neuropsychological test being considered as the dependent measure, and the cognitive function sensitive to these tests. Accordingly, interpretation of the functional significance of relationships between functional brain response on fMRI requires consideration of these factors at the very least.

That VWM-associated neural activation correlated with Stroop performance, but not with Trail-Making or HVLT performance suggests that the two tasks have certain common cognitive demands that affect the intensity of neural activation occurring during 2-back performance. The Stroop, Trail-Making, and HVLT tests are widely used in the clinical neuropsychological assessment of brain disorders. The Stroop test requires the inhibition of interfering incongruent stimulus characteristics, caused by color-word mixture of the word stimuli. People who experience difficulty with such inhibitory control will be slowed when performing the Stroop interference task. The inhibition of interference is not generally considered to be the primary cognitive demand associated with VWM, and 2-back performance in particular. Trail-Making has other attentional and executive control demands, including spatial selective attention and sequencing. While Trail-Making performance may be vulnerable to interference as well, the primary cognitive demands of this test are quite different. Trail-Making A is a relatively easy task that can usually be performed with minimal effort, and performance is largely dependent on the ability to selectively attend to spatial stimuli and to persist in maintaining a number sequence over a relatively short duration. Trail-Making B is a response alternation task that has additional cognitive demands associated with switching between numbers and letters in sequence, requiring the ability to shift sets rapidly, a component process underlying executive control. Therefore, the current finding that VWM-associated neural activation was only associated with Stroop performance suggests that processes underlying working memory in HIV+ adults may be vulnerable to the specific effects of interference. HIV may affect inhibitory control systems of the brain that impact performance on the Stroop test and also alter neural activation during the 2-back task.

Neural activation of VWM-related brain regions during the 2-back and of the PCC during rest was associated neuropsychological performance in HIV+ adults, though in different cognitive domains. Activation of the PCC during rest is noteworthy given that this brain region has been implicated for learning and memory, and is affected in patients with amnestic disturbances due to neurodegenerative disease (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease)75–77. The current findings suggest that alterations in DMN function, specifically in the PCC, may contribute to HIV effects on learning and memory. Yet, the results also suggest a dissociation between affected brain areas and cognitive functions affected by HIV. That learning and memory deficits were associated with DMN during rest rather than VWM on the 2-back task is potentially important. Even though working memory is known to be a process that facilitates learning, functional brain activation of the VWM network during the 2-back proved to be less sensitive to learning performance than activation occurring in the PCC during rest. It is possible that the brain’s response during rest and its ability to benefit from “off-task” time has important implications for learning and memory in the context of HIV.

Why were the relationships between neural activation and neuropsychological performance evident only in HIV+ participants? One possibility is that HIV reduced the brain’s resilience and cognitive capacity in infected participants, and that these capacity limitations were most pronounced on tasks vulnerable to the effects of interference and that reduced inhibitory control contributes to this vulnerability. The absence of this relationship in HIV-seronegative controls was likely due to their having better cognitive capacity that exceeded levels necessary for performance of the 2-back task – a possibility supported by the finding that HIV+ participants had weaker neuropsychological performance than HIV-seronegative controls on the Stroop and HVLT tests. However, the fact that the relationship with HVLT learning was evident during rest suggests that the observed relationship cannot be fully explained by greater activation associated with cognitive task demands.

Consideration of the relationship between activation during the effortful VWM task and during rest may provide insight into these effects. Our a priori hypothesis was that difference in the intensity of activation occurring during the cognitively demanding VWM task and deactivation during rest would be an indicator of neural dynamic range. The rationale for this was that adverse effects of HIV on brain function may occur not only with respect to cognitive engagement relative to task demands, but also due to difficulties with disengagement from the task or from extrinsic interference more generally during periods of rest. To derive an index of dynamic range, it was necessary to take measurements from brain regions that have been functionally linked to each of these cognitive conditions. Averaging the maximum intensity levels across the ACC, DLPFC and IPL bilaterally provided a single index of activation for the whole VWM network that could be contrasted with PCC activation during rest. The larger the differential between activation during these two conditions, the greater the dynamic range. We believe that dynamic range reflects the extent of change in brain activation that occurs when people shift between cognitive states; in this case the shift between working memory operations and rest. Greater dynamic range may have adaptive value. A limited dynamic range may result in inefficiency of neural processing when state changes occur due to interference of one state on the other. For example, failure to efficiently shift from DMN during rest to activation of the VWM network during working memory performance would likely reduce the ability of the brain to optimally allocate resources to the cognitive task demands.

As hypothesized, the derived DRM metric was significantly associated with neuropsychological performance in the HIV+ participants in its own right. Even more noteworthy, DRM was associated with both Stroop and HVLT performance, such that greater dynamic range corresponds with better performance on these tasks. By combining information from neural activation occurring during the high and low states of cognitive demand, we were able to account for neuropsychological performance in two different cognitive domains, verbal learning and inhibitory control. Given that PCC activation intensity was based on the aggregation of all rest periods between 0-back and 2-back blocks, it likely not only was an indicator of the resting state itself, but also the brain’s ability to disengage from the active task conditions.

Overall, the results of this study extend our past findings regarding HIV-associated brain dysfunction from analysis of neural activation on fMRI during an n-back working memory paradigm64. We previously observed fMRI abnormalities among HIV+ adults depending on task comparisons between 2-back, 0-back and rest. A reduction in the dynamic range of neural response on the 2-back relative to the other conditions was observed among HIV+ adults, which was attributable to reduced neural efficiency when challenging effortful task demands existed, and a finding consistent with earlier research63. Reduced neural dynamic range was most evident when VWM-associated activation was contrasted with activation during rest. The intensity of neural activation response during VWM relative to the other conditions, and also the effect of dynamic neural range, varied as a function of HIV-associated clinical factors, including nadir CD4, viral load, time since HIV diagnosis, and comorbid HCV. Linking fMRI response to specific HIV-associated clinical factors provided strong evidence that current and past HIV disease severity were responsible for functional brain abnormalities among HIV+ adults, as opposed to some other unrelated factors.

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the study findings. While the overall sample size was quite large compared to most fMRI studies in the research literature, a larger sample of HIV+ adults would enable analysis of the influence of all HIV-associated clinical factors on the findings. A larger sample size would also allow for equating performance across all participants, enabling task difficulty effects to be determined for each participant. The exclusion for excessive head motion, image artifact, and failure to perform adequately on the n-back tasks, though necessary for the neuroimaging analyses, has some experimental implications, as those excluded for these reasons tended to be the most impaired. Participants with HCV were excluded to reduce sample heterogeneity and confounding effects of this co-morbidity on the effects, which reduced the sample size further. Given our previous findings showing HCV co-infection associated with greater abnormalities on fMRI64, even larger effects may have been found if they were not excluded. However, including HCV+ participants would confound interpretation of the effects of HIV. Similarly, the exclusion of participants with current substance abuse reduced this obvious confound, but also restricted the sample so that it was not fully representative of the population of HIV+ adults, and may have had some impact on the study findings. We did not exclude for past history of substance abuse or dependence, though comparisons of people with and without such history yielded minimal differences in observed effects. Lastly, the present study was performed in the context of a larger R01 project, and due to the in-scanner time limitation of 60 minutes, the fMRI n-back paradigm did not include a one-back and three-back task to fully characterize the neural effect of increasing demand. This limitation should certainly be addressed in future studies of this population to determine if the findings of past research indicating that comparing 0-back to 2-back tasks remains sufficient for investigating the effects of working memory load in an efficient and cost-effective manner.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings from the current study provide strong evidence that brain function continues to be affected by HIV in the post-cART era4, and that functional neuroimaging with fMRI provides a potentially useful biomarker for assessing HIV-associated brain dysfunction. The fMRI findings, particularly with respect to dynamic range, support the conclusion that HIV reduces neural efficiency and reduces cognitive reserve61,64. HIV+ adults appear to expend more cognitive resources on cognitive tasks, and also do not seem to benefit optimally from rest after cognitive engagement. Accordingly, beyond the failure of task-relevant attention and working memory networks, HIV-associated brain dysfunction may also involve dysregulation within self-directed attention networks (e.g., DMN) that can be functionally decoupled from active-task relevant networks86.

The current study demonstrates that the fMRI abnormalities that we previously observed among HIV+ adults are associated with neuropsychological test performance. When using functional neuroimaging to assess HIV-associated neurocognitive disturbances in future studies, it may be necessary to consider neural response both on- and off-task, and to examine the relationship between these states via a metric such as dynamic range. The fact that neural activation occurring during both VWM and during rest periods occurring after each 2-back and 0-back task block was associated with test performance has potentially important implications for the use of fMRI as a clinical assessment tool. That study effects varied as a function of dynamic range of cortical activation with increasing task demand relative to rest also suggests HIV-associated brain dysfunction may not be fully revealed by examination of functional brain response on individual tasks (e.g., attention/vigilance and working memory) in isolation, or at a single level of difficulty.

In addition to extending understanding of the effects of HIV on the brain and cognition, the findings may make scientific and clinical contributions, including: 1) Characterizing the relationships between two different functional brain networks (i.e., VWM and DMN) within a single paradigm, including the effects tied to shifts between cognitive states.; 2) Characterization of the relationship of activation between two functional brain networks to performance in different cognitive domains assessed by neuropsychological testing. Examination of DMN activation and cognition has occurred in past resting state fMRI studies, and between VWM activation and neuropsychological performance in some prior studies that have employed the n-back. However, we are unaware of studies explicitly examining these relationships in the context of a single paradigm, especially in the context of HIV.; and 3) Derivation of a DRM metric that can be examined in future studies and ultimately may provide a useful clinical biomarker. The observed relationships between neural activation and neuropsychological test performance suggests that these fMRI metrics may be useful for predicting functional outcome in HIV+ adults. Conversely, the neurocognitive measures may be predictive of alterations in these fMRI metrics of brain dysfunction. Clinical trials aimed at testing the utility of such metrics would be valuable.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Cohen RA, Boland R, Paul R, et al. Neurocognitive performance enhanced by highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected women. AIDS. 2001;15(3):341–345. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200102160-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letendre SL, Ellis RJ, Everall I, Ances B, Bharti A, McCutchan JA. Neurologic complications of HIV disease and their treatment. Top HIV Med. 2009;17(2):46–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sacktor N, McDermott MP, Marder K, et al. HIV-associated cognitive impairment before and after the advent of combination therapy. J Neurovirol. 2002;8(2):136–142. doi: 10.1080/13550280290049615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark US, Cohen RA. Brain dysfunction in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: implications for the treatment of the aging population of HIV-infected individuals. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;11(8):884–900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clifford DB. HIV-associated neurocognitive disease continues in the antiretroviral era. Top HIV Med. 2008;16(2):94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heaton RK, Clifford DB, Franklin DR, Jr, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: CHARTER Study. Neurology. 2010;75(23):2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(1):3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robertson KR, Smurzynski M, Parsons TD, et al. The prevalence and incidence of neurocognitive impairment in the HAART era. AIDS. 2007;21(14):1915–1921. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32828e4e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devlin KN, Gongvatana A, Clark US, et al. Neurocognitive effects of HIV, hepatitis C, substance use history. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2012;18(1):68–78. doi: 10.1017/S1355617711001408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wendelken LA, Valcour V. Impact of HIV and aging on neuropsychological function. J Neurovirol. 2012;18(4):256–263. doi: 10.1007/s13365-012-0094-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harezlak J, Buchthal S, Taylor M, et al. Persistence of HIV-associated cognitive impairment, inflammation, and neuronal injury in era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. AIDS. 2011;25(5):625–633. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283427da7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin EM, Robertson LC, Edelstein HE, et al. Performance of patients with early HIV-1 infection on the Stroop Task. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1992;14(5):857–868. doi: 10.1080/01688639208402867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin E, Sorenson D, Edelstein H, et al. Decision-making speed in HIV-infection: a preliminary report. AIDS. 1992;6:109–113. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin EM, DeHaan S, Vassileva J, Gonzalez R, Weller J, Bechara A. Decision making among HIV+ drug using men who have sex with men: a preliminary report from the Chicago Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2013;35(6):573–583. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2013.799122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin EM, Pitrak DL, Novak RM, Pursell KJ, Mullane KM. Reaction times are faster in HIV-seropositive patients on antiretroviral therapy: A preliminary report. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1999;21(5):730–735. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.5.730.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin EM, Pitrak DL, Pursell KJ, Andersen BR, Mullane KM, Novak RM. Information processing and antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1998;4(4):329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valcour V, Sithinamsuwan P, Letendre S, Ances B. Pathogenesis of HIV in the central nervous system. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(1):54–61. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0070-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valcour VG, Shiramizu BT, Shikuma CM. HIV DNA in circulating monocytes as a mechanism to dementia and other HIV complications. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87(4):621–626. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0809571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Tang XP, McArthur JC, Scott J, Gartner S. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp160 sequences from a patient with HIV dementia: evidence for monocyte trafficking into brain. J Neurovirol. 2000;6(Suppl 1):S70–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ances BM, Ortega M, Vaida F, Heaps J, Paul R. Independent effects of HIV, aging, and HAART on brain volumetric measures. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59(5):469–477. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318249db17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ances BM, Benzinger TL, Christensen JJ, et al. 11C-PiB imaging of human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorder. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(1):72–77. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Gongvatana A, et al. Cerebral metabolite abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus are associated with cortical and subcortical volumes. J Neurovirol. 2010;16(6):435–444. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.520817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Schifitto G, et al. Effects of nadir CD4 count and duration of human immunodeficiency virus infection on brain volumes in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era. J Neurovirol. 2010;16(1):25–32. doi: 10.3109/13550280903552420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson PM, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, et al. 3D mapping of ventricular and corpus callosum abnormalities in HIV/AIDS. Neuroimage. 2006;31(1):12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker JT, Sanders J, Madsen SK, et al. Subcortical brain atrophy persists even in HAART-regulated HIV disease. Brain Imaging Behav. 2011;5(2):77–85. doi: 10.1007/s11682-011-9113-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller-Oehring EM, Schulte T, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Callosal degradation in HIV-1 infection predicts hierarchical perception: a DTI study. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(4):1133–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen RA, Harezlak J, Gongvatana A, et al. Cerebral metabolite abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus are associated with cortical and subcortical volumes. J Neurovirol. 2010;16(6):435–444. doi: 10.3109/13550284.2010.520817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heindel WC, Jernigan TL, Archibald SL, Achim CL, Masliah E, Wiley CA. The relationship of quantitative brain magnetic resonance imaging measures to neuropathologic indexes of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Neurol. 1994;51(11):1129–1135. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540230067015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jernigan TL, Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, et al. Clinical factors related to brain structure in HIV: the CHARTER study. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(3):248–257. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0032-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson PM, Dutton RA, Hayashi KM, et al. Thinning of the cerebral cortex visualized in HIV/AIDS reflects CD4+ T lymphocyte decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(43):15647–15652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502548102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gongvatana A, Harezlak J, Buchthal S, et al. Progressive cerebral injury in the setting of chronic HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. J Neurovirol. 2013;19(3):209–218. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0162-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Towgood KJ, Pitkanen M, Kulasegaram R, et al. Mapping the brain in younger and older asymptomatic HIV-1 men: frontal volume changes in the absence of other cortical or diffusion tensor abnormalities. Cortex. 2012;48(2):230–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker JT, Maruca V, Kingsley LA, et al. Factors affecting brain structure in men with HIV disease in the post-HAART era. Neuroradiology. 2012;54(2):113–121. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0854-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ragin AB, Du H, Ochs R, et al. Structural brain alterations can be detected early in HIV infection. Neurology. 2012;79(24):2328–2334. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318278b5b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Filippi CG, Ulug AM, Ryan E, Ferrando SJ, van Gorp W. Diffusion tensor imaging of patients with HIV and normal-appearing white matter on MR images of the brain. Ajnr. 2001;22(2):277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pfefferbaum A, Rosenbloom MJ, Adalsteinsson E, Sullivan EV. Diffusion tensor imaging with quantitative fibre tracking in HIV infection and alcoholism comorbidity: synergistic white matter damage. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2007;130(Pt 1):48–64. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV, Hedehus M, Lim KO, Adalsteinsson E, Moseley M. Age-related decline in brain white matter anisotropy measured with spatially corrected echo-planar diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2000;44(2):259–268. doi: 10.1002/1522-2594(200008)44:2<259::aid-mrm13>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pomara N, Crandall DT, Choi SJ, Johnson G, Lim KO. White matter abnormalities in HIV-1 infection: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2001;106(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(00)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ragin AB, Wu Y, Storey P, Cohen BA, Edelman RR, Epstein LG. Diffusion tensor imaging of subcortical brain injury in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(3):292–298. doi: 10.1080/13550280590953799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segura B, Jurado MA, Freixenet N, Falcon C, Junque C, Arboix A. Microstructural white matter changes in metabolic syndrome: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurology. 2009;73(6):438–444. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b163cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sexton CE, Kalu UG, Filippini N, Mackay CE, Ebmeier KP. A meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiology of aging. 2011;32(12):2322 e2325–2318. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tate DF, Conley J, Paul RH, et al. Quantitative diffusion tensor imaging tractography metrics are associated with cognitive performance among HIV-infected patients. Brain Imaging Behav. 2010;4(1):68–79. doi: 10.1007/s11682-009-9086-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xuan A, Wang GB, Shi DP, Xu JL, Li YL. Initial study of magnetic resonance diffusion tensor imaging in brain white matter of early AIDS patients. Chinese medical journal. 2013;126(14):2720–2724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fennema-Notestine C, Ellis RJ, Archibald SL, et al. Increases in brain white matter abnormalities and subcortical gray matter are linked to CD4 recovery in HIV infection. J Neurovirol. 2013;19(4):393–401. doi: 10.1007/s13365-013-0185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Y, Wang M, Li H, et al. Accumulation of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage in the frontal cortex cells of patients with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Brain Res. 2012;1458:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gongvatana A, Cohen RA, Correia S, et al. Clinical contributors to cerebral white matter integrity in HIV-infected individuals. J Neurovirol. 2011;17(5):477–486. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0055-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gongvatana A, Schweinsburg BC, Taylor MJ, et al. White matter tract injury and cognitive impairment in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J Neurovirol. 2009;15(2):187–195. doi: 10.1080/13550280902769756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McMurtray A, Nakamoto B, Shikuma C, Valcour V. Cortical atrophy and white matter hyperintensities in HIV: the Hawaii Aging with HIV Cohort Study. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases : the official journal of National Stroke Association. 2008;17(4):212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seider TR, Gongvatana A, Woods AJ, et al. Age exacerbates HIV-associated white matter abnormalities. J Neurovirol. 2016;22(2):201–212. doi: 10.1007/s13365-015-0386-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Haddow LJ, Dudau C, Chandrashekar H, et al. Cross-Sectional Study of Unexplained White Matter Lesions in HIV Positive Individuals Undergoing Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014 doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olsen WL, Longo FM, Mills CM, Norman D. White matter disease in AIDS: findings at MR imaging. Radiology. 1988;169(2):445–448. doi: 10.1148/radiology.169.2.3174991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang L, Ernst T, Leonido-Yee M, Walot I, Singer E. Cerebral metabolite abnormalities correlate with clinical severity of HIV-1 cognitive motor complex. Neurology. 1999;52(1):100–108. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson AM, Harezlak J, Bharti A, et al. Plasma and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers Predict Cerebral Injury in HIV-Infected Individuals on Stable Combination Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(1):29–35. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harezlak J, Cohen R, Gongvatana A, et al. Predictors of CNS injury as measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in the setting of chronic HIV infection and CART. J Neurovirol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0246-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yiannoutsos CT, Ernst T, Chang L, et al. Regional patterns of brain metabolites in AIDS dementia complex. Neuroimage. 2004;23(3):928–935. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Paul RH, Ernst T, Brickman AM, et al. Relative sensitivity of magnetic resonance spectroscopy and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging to cognitive function among nondemented individuals infected with HIV. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2008;14(5):725–733. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708080910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paul RH, Yiannoutsos CT, Miller EN, et al. Proton MRS and neuropsychological correlates in AIDS dementia complex: evidence of subcortical specificity. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2007;19(3):283–292. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tracey I, Hamberg LM, Guimaraes AR, et al. Increased cerebral blood volume in HIV-positive patients detected by functional MRI. Neurology. 1998;50(6):1821–1826. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ernst T, Chang L, Arnold S. Increased glial metabolites predict increased working memory network activation in HIV brain injury. Neuroimage. 2003;19(4):1686–1693. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang L, Tomasi D, Yakupov R, et al. Adaptation of the attention network in human immunodeficiency virus brain injury. Ann Neurol. 2004;56(2):259–272. doi: 10.1002/ana.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ernst T, Yakupov R, Nakama H, et al. Declined neural efficiency in cognitively stable human immunodeficiency virus patients. Ann Neurol. 2009;65(3):316–325. doi: 10.1002/ana.21594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang L, Speck O, Miller EN, et al. Neural correlates of attention and working memory deficits in HIV patients. Neurology. 2001;57(6):1001–1007. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tomasi D, Chang L, de Castro Caparelli E, Telang F, Ernst T. The human immunodeficiency virus reduces network capacity: acoustic noise effect. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(2):419–423. doi: 10.1002/ana.20766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Caldwell JZ, Gongvatana A, Navia BA, et al. Neural dysregulation during a working memory task in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive and hepatitis C coinfected individuals. J Neurovirol. 2014;20(4):398–411. doi: 10.1007/s13365-014-0257-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ances B, Vaida F, Ellis R, Buxton R. Test-retest stability of calibrated BOLD-fMRI in HIV− and HIV+ subjects. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2156–2162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ances BM, Roc AC, Korczykowski M, Wolf RL, Kolson DL. Combination antiretroviral therapy modulates the blood oxygen level-dependent amplitude in human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive patients. J Neurovirol. 2008;14(5):418–424. doi: 10.1080/13550280802298112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chang L, Holt JL, Yakupov R, Jiang CS, Ernst T. Lower cognitive reserve in the aging human immunodeficiency virus-infected brain. Neurobiology of aging. 2013;34(4):1240–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chang L, Yakupov R, Nakama H, Stokes B, Ernst T. Antiretroviral treatment is associated with increased attentional load-dependent brain activation in HIV patients. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008;3(2):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9092-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ellis RJ, Badiee J, Vaida F, et al. CD4 nadir is a predictor of HIV neurocognitive impairment in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2011;25(14):1747–1751. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834a40cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sun B, Abadjian L, Rempel H, Calosing C, Rothlind J, Pulliam L. Peripheral biomarkers do not correlate with cognitive impairment in highly active antiretroviral therapy-treated subjects with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Neurovirol. 2010;16(2):115–124. doi: 10.3109/13550280903559789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Crum-Cianflone NF, Moore DJ, Letendre S, et al. Low prevalence of neurocognitive impairment in early diagnosed and managed HIV-infected persons. Neurology. 2013;80(4):371–379. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827f0776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cohen RA, de la Monte S, Gongvatana A, et al. Plasma cytokine concentrations associated with HIV/hepatitis C coinfection are related to attention, executive and psychomotor functioning. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2011;233(1–2):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McArthur JC, McDermott MP, McClernon D, et al. Attenuated central nervous system infection in advanced HIV/AIDS with combination antiretroviral therapy. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(11):1687–1696. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.11.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim H. Default network activation during episodic and semantic memory retrieval: A selective meta-analytic comparison. Neuropsychologia. 2016;80:35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tam A, Dansereau C, Badhwar A, et al. Common Effects of Amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment on Resting-State Connectivity Across Four Independent Studies. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:242. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Badhwar A, Tam A, Dansereau C, Orban P, Hoffstaedter F, Bellec P. Resting-state network dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2017;8:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heaton RK, Miller SW, Taylor MJ, Grant I. Revised Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographically Adjusted Neuropsychological Norms for African American and Caucasian Adults. Lutz, Fl: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessment (3rd ed) 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 80.RM R. Trail Making Test. Tuscon, Az: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Golden CJ. Stroop Color and Word Test. Chicago, IL: Stoelting; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Benedict RHBSA, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test Revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1998;12:43–55. 1998;12:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Heaton RK, Grant I, Butters N, et al. The HNRC 500--neuropsychology of HIV infection at different disease stages. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 1995;1(3):231–251. doi: 10.1017/s1355617700000230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Blackstone K, Moore DJ, Franklin DR, et al. Defining neurocognitive impairment in HIV: deficit scores versus clinical ratings. Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;26(6):894–908. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.694479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Blazer DG, Yaffe K, Liverman CT, editors. Cognitive Aging: Progress in Understanding and Opportunities for Action. Washington (DC): 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fox MD, Zhang D, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME. The global signal and observed anticorrelated resting state brain networks. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101(6):3270–3283. doi: 10.1152/jn.90777.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.