Abstract

Background

Three-quarters of the ≥50 programs that use micronutrient powders (MNPs) integrate MNPs into infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programs, with limited research on impacts on IYCF practices.

Objective

This study assessed changes in IYCF practices in 2 districts in Nepal that were part of a post-pilot scale-up of an integrated IYCF-MNP program.

Methods

This analysis used cross-sectional surveys (n = 2543 and 2578 for baseline and endline) representative of children aged 6–23 mo and their mothers in 2 districts where an IYCF program added MNP distributions through female community health volunteers (FCHVs) and health workers (HWs). Multivariable log-binomial models estimated prevalence ratios comparing reported IYCF at endline with baseline and at endline on the basis of exposure to different sources of IYCF information. Mothers who received FCHV-IYCF counseling with infrequent (≤1 time/mo) and frequent (>1 time/mo) interactions were compared with mothers who never received FCHV-IYCF counseling. The receipt of HW-IYCF counseling and receipt of MNPs from an FCHV (both yes or no) were also compared.

Results

The prevalence of minimum dietary diversity (MDD) and minimum acceptable diet (MAD) was significantly higher at endline than at baseline. In analyses from endline, compared with mothers who never received FCHV counseling, only mothers in the frequent FCHV-IYCF counseling group were more likely to report feeding the minimum meal frequency (MMF) and MAD, with no difference for the infrequent FCHV-IYCF counseling group in these indicators. HW-IYCF counseling was not associated with these indicators. Mothers who received MNPs from their FCHV were more likely to report initiating solid foods at 6 mo and feeding the child the MDD, MMF, and MAD compared with mothers who did not, adjusting for HW- and FCHV-IYCF counseling and demographic covariates.

Conclusions

Incorporating MNPs into the Nepal IYCF program did not harm IYCF and may have contributed to improvements in select practices. Research that uses experimental designs should verify whether integrated IYCF-MNP programs can improve IYCF practices.

Keywords: infant and young child feeding, micronutrient powders, point-of-use fortification, home-based fortification, complementary feeding, dietary diversity

Introduction

Approximately one-third of the world's population is deficient in key vitamins and minerals (1), with women of reproductive age and children suffering the largest burden. Among children aged 6–59 mo in low- and middle-income countries, an estimated 29% are deficient in vitamin A (2)

and 43% are anemic, with approximately half of cases estimated to be due to iron deficiency (3). Micronutrient deficiencies during the first 1000 d—from conception to 2 y of age—increase the risk of mortality and morbidity in childhood and also have life-long consequences for physical and cognitive development (4). The WHO recommends the introduction of solid and semisolid complementary foods for children at 6 mo of age, because breast milk is no longer sufficient to meet children's nutritional needs during this critical time period (5, 6). In resource-limited settings, however, micronutrient-rich foods, such as animal-source foods, are often inaccessible for families, and when they are available, they often are not provided in sufficient quantities to young children (7, 8). Currently, only 1 in 6 children aged 6–23 mo in low- and middle-income countries are fed the minimum acceptable diet [MAD; defined as minimum meal frequency (MMF) of solid or semisolid foods and minimum dietary diversity (MDD)] (9). In the 2011 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey (the most recent survey before the impact evaluation described in this article), rates of MDD and MMF for children aged 6–23 mo were 28% and 78%, respectively; the prevalence of anemia in children aged 6–59 mo was 46.2% (10).

Interventions designed to address multiple micronutrient deficiencies have gained particular attention recently given the fact that multiple deficiencies often cluster within the same individuals and communities (11–13). Micronutrient powders (MNPs) are particularly attractive because the single-dose packets are light-weight, shelf-stable, and can be mixed into most semisolid foods and, when prepared correctly, should not affect taste, smell, color, or texture (14). On the basis of the findings from meta-analyses of efficacy trials that show that MNPs can reduce the prevalence of anemia and iron deficiency among children aged 6–24 mo by >25% and 50%, respectively (15), the WHO now recommends the use of MNPs for children in this age group where their prevalence of anemia is ≥20% (16). Globally, MNP programs now reach millions of children each year (17, 18). However, there is limited research from programs that use MNPs at scale (19–26), and much of the literature focuses on pilot programs, and not national or subnational programs in the process of scale-up (27, 28).

It has been proposed that incorporating MNPs into infant and young child feeding (IYCF) programs could contribute to improved IYCF practices by establishing an enabling political and community environment to support IYCF programs (29), and by the integrated IYCF-MNP delivery, which often includes enhanced IYCF-MNP training for facility-based and community health workers (CHWs), behavior change materials that re-enforce key IYCF messages, and by the introduction of a tangible good (MNP) for CHWs to distribute in the community, which may, in turn, improve the demand for and delivery of CHW services. Few studies, however, have assessed IYCF practices in the context of integrated IYCF-MNP programs (30, 31). Globally, approximately three-quarters of the 59 programs that use MNPs are health sector programs that have integrated MNPs into IYCF programs (18). To date, the few studies assessing the impact of integrated interventions on IYCF practices are from pilot programs (30, 31), which, due to their small scale, likely benefited from greater resources devoted to program implementation. In this study, we assessed the changes in maternal reported IYCF practices in 2 districts in Nepal that were part of a post-pilot scale-up of an integrated IYCF-MNP program.

Methods

Study population and data collection

The Nepal Ministry of Health (MoH), in collaboration with UNICEF, started developing an integrated IYCF-MNP program targeted at children aged 6–23 mo in 2009. In the first stage of program development, a feasibility study was conducted in 8 village development committees in 2 districts in 2009 to assess the acceptability of MNPs and to develop key messages and strategies for the development of the integrated IYCF-MNP program. This was followed by a pilot study in 6 districts from 2010 to 2011, which delivered MNPs through government-run health facilities and female community health volunteers (FCHVs) (21). Beginning in late 2012, the MoH and UNICEF began scaling up the integrated IYCF-MNP program, which, as of 2016, had reached 26 out of the country's 75 districts.

In Nepal, MNP has been locally branded as Baal Vita; each sachet of Baal Vita contains 15 micronutrients, including iron and zinc, at ∼1x the Recommended Nutrient Intake (32). The integrated IYCF-MNP program uses a cascade approach to train health workers and FCHVs with a manual based on the UNICEF community-based IYCF training tools (33), with additional modules on the appropriate storage, distribution, and use of MNPs adapted by the MoH for the Nepal context. Health workers and FCHVs are, in turn, responsible for counseling all mothers and community members in the intervention districts on IYCF and MNP and distributing 60 sachets of MNPs free of charge to all children aged 6–23 mo every 6 mo during regular child visits to health facilities and through FCHVs during mothers groups, home visits, and other community contact points. In accordance with national policy, FCHVs are expected to hold monthly mother and caregiver group meetings, where they use the IYCF-MNP counseling cards and flip charts to educate and counsel mothers on MNPs and complementary feeding. Given that FCHVs are unpaid volunteers, government policies also encourage, but do not require, that FCHVs conduct home visits or individual meetings elsewhere in the community if/when they have the time to do so.

The incorporation of MNPs into the IYCF training and program materials (including posters, pamphlets, and radio jingles) re-enforces several key IYCF messages, such as the timely introduction of complementary foods, because all MNP key messages emphasize beginning MNPs at 6 mo, as well as the importance of providing infants with a nutritious diet that includes frequent breastfeeding, a diverse diet, and the inclusion of a homemade “super flour” (cooking demonstrations teach mothers how to make the flour from lentils and rice and how to store and use it). The IYCF-MNP program also emphasizes adding MNPs to foods of a thick consistency (not soups) and responsive feeding behaviors (singing, talking to, and making eye contact with the child while feeding) as well as handwashing with soap before cooking, eating, and feeding as well as after using the bathroom.

The analyses presented here come from an impact evaluation—implemented by New ERA with technical assistance from the CDC—that was implemented in 2 of the 9 expansion districts where the IYCF-MNP program was initiated in 2013. Cross-sectional surveys representative of children aged 6–23 mo and their mothers in the 2 districts (Kapilvastu in the plains ecological zone and Achham in the hills ecological zone) were conducted before program initiation in December 2012 through February 2013 and then after 36 mo of program implementation in January and February 2016. Given the rapidly changing landscape of nutrition programs in Nepal, the stakeholders in the integrated IYCF-MNP program decided not to include “control” districts in the impact evaluation because it was highly likely that additional nutrition interventions would be rolled out throughout the country between the baseline and endline surveys.

The baseline and endline surveys both used a 2-stage cluster-sampling method. Population-proportion-to-size sampling was used to identify 40 clusters (based on government-defined wards) from each district. A census was then conducted in selected clusters to identify all children aged 6–23 mo. With the use of random sampling, 32 children in Achham and 34 in Kapilvastu were selected from each cluster at baseline, and 34 children from each cluster were selected in Kapilvastu and 33 in Achham at endline. There was no replacement for refusals or for clusters with less than the needed number of children.

During the baseline and endline surveys, trained survey interviewers who were not part of program implementation asked mothers about sociodemographic characteristics and IYCF knowledge and practices; at endline, mothers were also asked about program exposure, including details on the types of interactions they had with their FCHV and health facilities, as well as receipt and use of MNPs. To assess IYCF practices, mothers were given a standard questionnaire based on the WHO/UNICEF 2010 IYCF indicators (34). They were asked if they had ever breastfed their child and, if so, to recall when they initiated breastfeeding and whether they were still breastfeeding. For complementary foods, mothers were asked to recall when they first introduced solid or semisolid foods to their child and whether the child received any solid or semisolid foods in the previous day. Interviewers then asked about the frequency of solid and semisolid foods in the previous day, and whether the child consumed any items from the following 7 food groups: 1) grains, roots, and tubers; 2) legumes and nuts; 3) dairy products (milk, yogurt, and cheese); 4) flesh foods (meat, fish, poultry, and liver/organ meats); 5) eggs; 6) vitamin A–rich fruit and vegetables; and 7) other fruit and vegetables. In accordance with WHO/UNICEF indicators, MDD was defined as ≥4 food groups (out of 7) in the previous day; MMF as ≥2 times/d for breastfed infants aged 6–8 mo, ≥3 times/d for breastfed children aged 9–23 mo; and ≥4 times/d for nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mo. For breastfed children, MAD was defined as MMF and MDD; for nonbreastfed infants, MAD was defined as ≥2 milk feedings, MMF, and ≥4 out of 6 food groups (excluding the dairy food group) in the previous day. Mothers were also asked about micronutrient and IYCF knowledge as well as whether they engaged in any responsive feeding activities the previous day (yes or no questions pertaining to whether the mother talked to, sang to, or made eye contact with the child while feeding).

The first round of distributions of 60 MNP sachets to eligible children aged 6–23 mo took place in Achham and Kapilvastu in March 2013; however, subsequent distributions were interrupted due to a national stock-out related to issues with the international supplier (35). As a result, Achham and Kapilvastu did not have the expected second distribution in 2013, and they only had a partial distribution in the first half of 2014—both districts received unbranded emergency MNP stock with a Baal Vita sticker placed on the box, but only enough to provide a single box of 30 sachets to 50% and 72% of children aged 6–18 mo in Achham and Kapilvastu, respectively. During the MNP stock-out, the IYCF components of the intervention continued. New branded Baal Vita stock arrived in the country in March 2014, and a refresher training session for FCHVs and health workers was carried out. The program relaunched with full distributions in Kapilvastu and Achham in May and June 2014, providing the 2 districts with sufficient time for 3 complete distribution cycles (distribution of 60 MNP sachets every 6 mo) before the endline survey. In addition, in 2014, the multidistrict US Agency for International Development–funded integrated nutrition program Suaahara launched in Kapilvastu and Achham (36). Suaahara focused on mothers in the first 1000 d with a social behavior change and communication and sex and social inclusion program integrating programming across nutrition, health services, family planning, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), and agriculture/homestead food production. The Suaahara program provided additional IYCF trainings for health workers and FCHVs and supported IYCF key messages with mass media. FCHVs were the primary means of engaging the Suaahara target populations with social behavior change and communication activities. Thus, as part of both the Suaahara and integrated IYCF-MNP programs, FCHVs conducted group meetings, home visits, and food demonstrations to strengthen IYCF practices among mothers of children aged <23 mo.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Nepal Health Research Council for both the baseline and endline surveys. For each survey, survey enumerators described the purpose, procedures, risks, and benefits of the study and allowed mothers to ask questions before inviting mothers and children to participate in the survey. Mothers then provided written informed consent to enroll themselves and their children in the study. If the mothers were illiterate, then a witness signature was obtained.

Data analysis

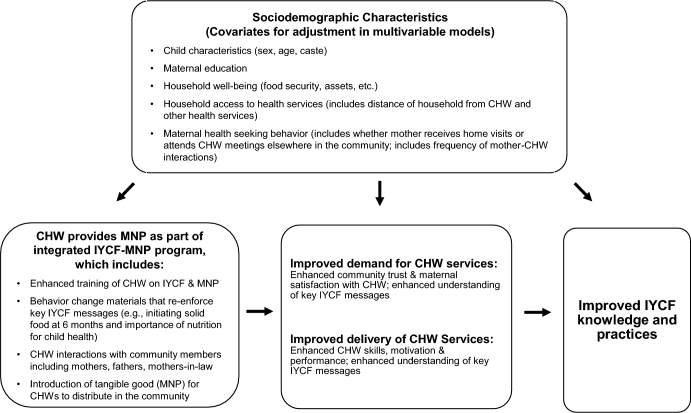

Frequencies and percentages of key demographic characteristics of the study sample in each district in the baseline and endline surveys were compared. Baseline (reference group) and endline IYCF knowledge and practices in each district were also compared by using log-binomial regressions to obtain prevalence ratios for categorical variables; differences of means were obtained from linear regression models. All models accounted for correlated errors within clusters with the use of an exchangeable correlation structure. Covariates for multivariable models (Figure 1) were selected a priori on the basis of a review of the literature and included child's sex, age, and caste; maternal education; household food insecurity level [based on the Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (37)]; and household asset tertile (developed from a principal components analysis based on household ownership of electricity, radio, television, mobile, refrigerator, table, chair, bed, sofa, watch, computer, fan, traditional grain miller, and bicycle).

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms through which CHW delivery of MNP can improve IYCF practices, which are used to guide variables in analytic models. CHW, community health worker; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; MNP, micronutrient powder.

To assess whether changes in IYCF knowledge and practices were associated with maternal exposure to different sources of IYCF information, cross-sectional analyses from the endline survey were conducted. We first compared IYCF knowledge and practices based on 3 categories of FCHV-IYCF counseling: 1) mothers who had never received IYCF counseling from their FCHV, 2) mothers who received IYCF counseling from their FCHV but had infrequent interactions with their FCHV (once per month or less), and 3) mothers who received IYCF counseling from their FCHV and also reported frequent interactions with their FCHV (at least twice per month). The prevalence of key IYCF knowledge and reported practices were compared by using log-binomial regression models to obtain prevalence ratios for categorical outcomes and linear regression models for differences of means for continuous outcomes (with the no-FCHV-IYCF counseling group as the reference). All models accounted for correlated errors within clusters with the use of an exchangeable correlation structure. For associational analyses, we first modeled the 2 districts separately, but when the districts showed similar trends, we combined the data from the 2 districts and included district as a covariate in the models. Because these analyses were not intended to be population-based estimates, we did not use sampling weights. All models include all of the covariates identified in Figure 1—namely, sociodemographic covariates (child's sex, age, and caste; maternal education; household food insecurity level; and household asset tertile), maternal health-seeking indicators (whether the mother received FCHV home visits, visited the FCHV elsewhere in the community, or both; and frequency of mother-FCHV interactions), as well as household access to health services (distance mother travels to see FCHV and distance she travels to the nearest health facility).

With the use of the same methods and covariates as the models assessing the relation between FCHV-IYCF counseling and maternal IYCF knowledge and practices, we also assessed whether mothers who received IYCF counseling from a health worker had better IYCF knowledge and practices than mothers who had not received IYCF counseling from a health worker, adjusting for sociodemographic and FCHV-level counseling indicators. Because frequent health center visits were less common (and likely reflected child illness and not necessarily exposure to IYCF counseling messages), we did not include frequency of mother–health worker interactions in these models.

Finally, we assessed whether the receipt of MNPs from an FCHV had an additional, independent association with maternal IYCF knowledge and reported practices, adjusting for receipt of IYCF counseling from FCHVs and health workers and other sociodemographic characteristics. Although the integrated IYCF-MNP program included multiple contact points with mothers, including at health facilities and through mass media, this article focuses on the distribution of MNPs through FCHVs for 3 reasons. First, previous analyses from the Nepal IYCF-MNP pilot program showed that attendance at FCHV mothers’ group meetings was an important predictor of MNP coverage and intake (21, 30), thus warranting additional analysis in the critical role of FCHVs. Second, almost all mothers in the endline survey reported contact with their FCHV at some point during the study period, and >80% of mothers who received MNP reported receiving it from their FCHV; and third, analysis of the FCHV-level service provision provides insight for program planners in other contexts who are considering the added value of pursuing community-based MNP distribution despite the program complexity and potential added burden on CHWs. We also conducted multivariable log-binomial regression models that included an interaction term for FCHV-IYCF counseling group (receipt of IYCF counseling with frequent interactions compared with no IYCF counseling or IYCF counseling with infrequent interactions) and MNP receipt from the FCHV (yes or no).

After finding an independent association between receiving MNPs from the FCHV and several important IYCF indicators, we conducted exploratory analyses to better elucidate the mechanism through which MNPs may influence the FCHV-mother relationship and ultimately IYCF practices. Specifically, we conducted multivariable log-binomial regression models for maternal satisfaction with her FCHV (because very few mothers reported being unsatisfied with their FCHV, our outcome was “very satisfied” compared with “satisfied” or “unsatisfied”). With the use of log-binomial regression models adjusted for all covariates shown in Figure 1, we also assessed whether receipt of MNPs from the FCHV or maternal perception of positive benefits in her child after using MNPs was associated with maternal satisfaction. We then independently assessed whether maternal satisfaction with her FCHV was a predictor of whether the mother fed her child the MAD. The point and interval estimates of the percentage of the association between receipt of MNPs from an FCHV and feeding the child the MAD that was mediated by maternal satisfaction were also estimated by using log-binomial regression models. All of the analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

A total of 2543 and 2577 households with children aged 6–23 mo, reflecting response rates of 97% and 96% of targeted children, participated in the baseline and endline surveys, respectively (Table 1). Half of mothers had no formal education, and the majority of households gained their income from agriculture. Households in Achham had fewer household assets and were less food secure than households in Kapilvastu. In the endline survey, we found that 45.9% and 65.3% of mothers in Kapilvastu and Achham, respectively, reported that they had discussed the feeding of their child with both a health worker and their FCHV. Another 8.3% in Kapilvastu and 8.0% in Achham had discussed child feeding with a health worker only, and 27.8% and 18.3% had discussed child feeding with an FCHV only. Only 18.1% of mothers in Kapilvastu and 8.5% of mothers in Achham had never discussed child feeding with either an FCHV or a health worker. Among mothers who had interacted with their FCHV (88.4% and 94.1% of all mothers in Kapilvastu and Achham, respectively), 61.0% and 33.6% had received home visits and 76.4% and 85.3% had traveled to see their FCHV elsewhere in the community in Kapilvastu and Achham, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and program exposure characteristics of children aged 6–23 mo and their mothers in the Kapilvastu and Achham districts, Nepal1

| Kapilvastu district | Achham district | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 (n = 1286) | 2016 (n = 1345) | 2013 (n = 1257) | 2016 (n = 1233) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Child's age | ||||

| 6–11 mo | 436 (33.9) | 402 (29.9) | 403 (32.1) | 418 (33.9) |

| 12–17 mo | 522 (40.6) | 519 (38.6) | 468 (37.2) | 448 (36.3) |

| 18–23 mo | 328 (25.5) | 424 (31.5) | 386 (30.7) | 367 (29.8) |

| Child's sex | ||||

| Male | 675 (52.5) | 718 (53.4) | 670 (53.3) | 651 (52.8) |

| Female | 611 (47.5) | 627 (46.6) | 587 (46.7) | 582 (47.2) |

| Ethnicity/caste | ||||

| Upper caste | 187 (14.5) | 189 (14.1) | 827 (65.8) | 840 (68.1) |

| Dalit hill/terai | 216 (16.8) | 220 (16.4) | 418 (33.3) | 379 (30.8) |

| Other | 883 (68.7) | 936 (69.6) | 12 (1.0) | 14 (1.1) |

| Maternal education | ||||

| No formal education | 751 (58.4) | 623 (46.4) | 863 (68.7) | 663 (53.8) |

| Primary education | 219 (17.0) | 280 (20.8) | 143 (11.4) | 151 (12.3) |

| Secondary education or higher | 316 (24.6) | 441 (32.8) | 251 (20.0) | 418 (33.9) |

| Number of people sharing a kitchen | ||||

| Tertile 1 (≤5 people) | 372 (28.9) | 418 (31.1) | 539 (42.9) | 568 (46.1) |

| Tertile 2 (6–7 people) | 320 (24.9) | 322 (23.9) | 373 (29.7) | 371 (30.1) |

| Tertile 3 (≥8 people) | 594 (46.2) | 605 (45.0) | 345 (27.5) | 292 (23.8) |

| Main source of household income | ||||

| Agriculture | 811 (63.1) | 769 (57.2) | 998 (79.4) | 737 (59.8) |

| Remittance | 93 (7.2) | 177 (13.2) | 143 (11.4) | 259 (21.0) |

| Casual wage labor | 233 (18.1) | 211 (15.7) | 42 (3.3) | 95 (7.7) |

| Other | 149 (11.6) | 188 (13.9) | 74 (5.9) | 142 (11.5) |

| Household food security level | ||||

| Food secure | 658 (51.2) | 908 (67.5) | 458 (36.4) | 486 (39.4) |

| Mildly food insecure | 130 (10.1) | 106 (7.9) | 196 (15.6) | 145 (11.8) |

| Moderately food insecure | 466 (36.2) | 207 (15.4) | 440 (35.0) | 248 (20.1) |

| Severely food insecure | 32 (2.5) | 124 (9.2) | 163 (13.0) | 354 (28.7) |

| Household assets tertile2 | ||||

| Tertile 1 (more assets) | 576 (44.8) | 543 (40.4) | 253 (20.1) | 374 (30.3) |

| Tertile 2 | 396 (30.8) | 607 (45.1) | 261 (20.8) | 379 (30.7) |

| Tertile 3 (fewer assets) | 314 (24.4) | 195 (14.5) | 743 (59.1) | 480 (38.9) |

| Program characteristics | ||||

| Mother has discussed the feeding of her child with | ||||

| Both her FCHV and a government health worker | — | 617 (45.9) | — | 805 (65.3) |

| Her FCHV only | — | 374 (27.8) | — | 225 (18.3) |

| A government health worker only | — | 111 (8.3) | — | 98 (8.0) |

| Neither her FCHV nor a government health worker | — | 243 (18.1) | — | 105 (8.5) |

| Frequency of mother-FCHV interactions focused on the child | ||||

| Less than once per month | — | 523 (38.9) | — | 315 (25.6) |

| Monthly | — | 403 (30.0) | — | 358 (29.0) |

| More than once per month | — | 419 (31.2) | — | 560 (45.2) |

| Among mothers who report having interactions with an FCHV (n = 1189 and 1154), mother reports the following type of interaction | ||||

| Home visits only | — | 281 (23.6) | — | 169 (14.6) |

| Visits elsewhere in the community only | — | 464 (39.0) | — | 650 (56.3) |

| Both | — | 444 (37.4) | — | 335 (29.0) |

| Mother received MNP for the child | — | 732 (54.4) | — | 903 (73.2) |

| Mother received MNP ≥2 times (among children aged ≥12 mo only; n = 943 and 815) | — | 269 (20.0) | — | 434 (35.3) |

| Among mothers who received MNP for the child (n = 731 and 900) | ||||

| Mother identifies FCHV as primary source | — | 640 (87.6) | — | 744 (82.7) |

| Mother received MNP for the child in last 6 mo | — | 597 (82.7) | — | 769 (85.7) |

| Child consumed MNP | — | 718 (98.2) | — | 877 (97.6) |

| Among children who consumed MNP | ||||

| Mother reported a positive effect of MNP3 (n = 701 and 863) | — | 357 (50.9) | — | 460 (53.3) |

| Mother reported a negative effect of MNP4 (n = 705 and 852) | — | 232 (32.9) | — | 302 (35.5) |

1All values are frequencies [n (%)]. FCHV, female community health volunteer; MNP, micronutrient powder.

2Household assets tertile was determined from principal components analysis, which included questions on whether the household had a radio, television, mobile phone, refrigerator, table, chair, bed, sofa, watch, computer, fan, rice miller, bicycle, and electricity.

3Commonly reported positive effects of MNP include increased strength, immunity, cognitive capacity, and appetite in children.

4Commonly reported negative effects include loose stools, nausea, and vomiting.

Approximately half of mothers in Kapilvastu and three-quarters in Achham received MNPs for the eligible child at least once during the project period, >80% of whom received MNPs from their FCHV. Among children aged 12–23 mo (those eligible to receive multiple MNP distributions), 20.0% and 35.3% had received multiple distributions in Kapilvastu and Achham, respectively. Among mothers who had tried feeding MNPs to their child, half reported a positive effect on their child, such as improvements in health, strength, or appetite, and one-third reported negative effects, such as loose stools or vomiting.

Comparing endline with baseline, both districts had higher levels of maternal report of select optimal IYCF knowledge and practices even after adjustment for child's sex, caste, and age; maternal education; and household food insecurity score and asset tertile (Table 2). Of particular note, mothers in the endline survey in both districts were significantly more likely to report feeding their child the MDD (≥4 food groups) in the previous day than mothers at baseline [adjusted prevalence ratio (APR) (95% CI): 1.48 (1.33, 1.66), P < 0.001, and 1.19 (1.06, 1.34), P = 0.004, in Kapilvastu and Achham, respectively]. Specifically, in Kapilvastu, mothers in the endline survey were significantly more likely to report feeding their child eggs, meat and flesh foods, dairy, and vitamin A–rich fruit and vegetables than mothers in the baseline survey, with an increase in the mean number of food groups of +0.41 (95% CI: 0.30, 0.52; P < 0.001), whereas in Achham, mothers in the endline survey were significantly more likely to report feeding their child eggs, with an increase in the mean number of food groups of +0.11 (95% CI: 0.00, 0.22; P = 0.047). Mothers in both districts were also significantly more likely to feed their children the MAD [APR (95% CI): 1.77 (1.52, 2.07), P < 0.001, in Kapilvastu and 1.19 (1.02, 1.39), P = 0.02, in Achham]. In Kapilvastu, they were also more likely to feed their children the MMF (APR: 1.26; 95% CI: 1.13, 1.40; P < 0.001). Other improvements in IYCF practices from baseline to endline in both districts include the increased likelihood that mothers fed their children homemade “super flour” or engaged in responsive feeding activities (talking to, singing to, eye contact with the child) during feeding the previous day, as well as maternal report that she initiated breastfeeding within 1 h of birth and began complementary foods at 6 mo.

TABLE 2.

Comparing maternal IYCF knowledge and reported practices in Kapilvastu and Achham districts in Nepal at endline compared with baseline among mothers of children aged 6–23 mo1

| Kapilvastu district | Achham district | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 (n = 1286) | 2016 (n = 1345) | APR or difference of means (95% CI)2 | P | 2013 (n = 1257) | 2016 (n = 1233) | APR or difference of means (95% CI)2 | P | |

| Maternal nutrition and IYCF knowledge | ||||||||

| Identifies 6 mo as appropriate age to introduce complementary foods | 648 (50.5) | 1016 (75.9) | 1.39 (1.30, 1.48) | <0.001 | 799 (63.7) | 1106 (89.7) | 1.40 (1.31, 1.49) | <0.001 |

| Has heard of iron | 1116 (86.8) | 1121 (83.4) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.08 | 790 (62.9) | 1023 (83.0) | 1.30 (1.20, 1.40) | <0.001 |

| Is able to identify a benefit of iron | 1066 (82.9) | 1103 (82.0) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | 0.35 | 709 (56.4) | 1001 (81.2) | 1.40 (1.29, 1.53) | <0.001 |

| Identifies the following as a source of iron | ||||||||

| Meat, fish, or liver | 571 (44.4) | 779 (57.9) | 1.18 (1.09, 1.28) | <0.001 | 503 (40.0) | 678 (55.0) | 1.25 (1.15, 1.37) | <0.001 |

| Pulses | 333 (25.9) | 568 (42.2) | 1.48 (1.32, 1.66) | <0.001 | 380 (30.2) | 626 (50.8) | 1.56 (1.41, 1.74) | <0.001 |

| Green leafy vegetables | 737 (57.3) | 726 (54.0) | 0.91 (0.85, 0.98) | 0.01 | 409 (32.5) | 695 (56.4) | 1.64 (1.48, 1.81) | <0.001 |

| Maternal report of IYCF practices | ||||||||

| Infant feeding history | ||||||||

| Mother reports breastfeeding ≤1 h after birth | 495 (38.6) | 860 (64.6) | 1.60 (1.47, 1.74) | <0.001 | 679 (54.2) | 981 (80.5) | 1.44 (1.36, 1.53) | <.0001 |

| Mother reports introducing complementary foods at 6 mo | 432 (35.9) | 834 (64.7) | 1.68 (1.53, 1.84) | <0.001 | 603 (48.6) | 998 (82.9) | 1.67 (1.54, 1.82) | <0.001 |

| Infant feeding in previous 24 h | ||||||||

| Child was breastfed | 1210 (94.2) | 1249 (93.6) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.80 | 1219 (97.0) | 1189 (97.3) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.69 |

| Child consumed3 | ||||||||

| Flesh foods including chicken, mutton, and bufalo | 145 (12.4) | 221 (17.6) | 1.26 (1.04, 1.55) | 0.02 | 72 (6.0) | 105 (9.1) | 1.30 (0.97, 1.76) | 0.08 |

| Dairy | 370 (31.5) | 512 (40.7) | 1.12 (1.03, 1.21) | 0.009 | 596 (49.5) | 640 (55.2) | 1.03 (0.96, 1.10) | 0.44 |

| Eggs | 69 (5.9) | 220 (17.5) | 2.50 (1.92, 3.26) | <0.001 | 31 (2.6) | 113 (9.8) | 3.10 (2.08, 4.62) | <0.001 |

| Legumes | 968 (82.5) | 1091 (86.7) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.27 | 880 (73.1) | 903 (77.9) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.08) | 0.17 |

| Vitamin A–rich fruit and vegetables | 245 (20.9) | 608 (48.3) | 2.33 (2.05, 2.65) | <0.001 | 666 (55.3) | 632 (54.5) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 0.78 |

| Other fruit and vegetables | 371 (31.6) | 355 (28.2) | 0.84 (0.74, 0.95) | 0.004 | 139 (11.5) | 140 (12.1) | 0.92 (0.74, 1.15) | 0.47 |

| Grains, roots, or tubers | 1168 (99.6) | 1244 (98.9) | 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) | 0.02 | 1204 (100.0) | 1147 (99.0) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.001 |

| Mean number of food groups consumed3 | 2.84 ± 1.04 | 3.38 ± 1.24 | 0.41 (0.30, 0.52) | <0.001 | 2.98 ± 0.98 | 3.17 ± 1.07 | 0.11 (0.00, 0.22) | 0.047 |

| Minimum dietary diversity (≥4 food groups)3,4 | 289 (24.6) | 547 (43.5) | 1.48 (1.33, 1.66) | <0.001 | 321 (26.7) | 423 (36.5) | 1.19 (1.06, 1.34) | 0.004 |

| Mean frequency of solid/semisolid food5 | 2.54 ± 0.94 | 2.73 ± 1.21 | 0.21 (0.08, 0.33) | <0.001 | 2.74 ± 0.87 | 2.70 ± 1.19 | -0.04 (-0.15, 0.07) | 0.45 |

| Minimum meal frequency3,5 | 527 (45.0) | 744 (55.8) | 1.26 (1.13, 1.40) | <0.001 | 692 (57.5) | 686 (56.2) | 1.02 (0.95, 1.09) | 0.62 |

| Minimum acceptable diet3,6 | 169 (14.5) | 375 (30.1) | 1.77 (1.52, 2.07) | <0.001 | 222 (18.5) | 282 (24.6) | 1.19 (1.02, 1.39) | 0.02 |

| Child ate homemade “super flour” yesterday | 64 (5.0) | 153 (11.4) | 1.77 (1.35, 2.32) | <0.001 | 34 (2.7) | 226 (18.3) | 6.33 (4.41, 9.09) | <0.001 |

| Mother reported the following responsive feeding activities | ||||||||

| Eye contact with child | 753 (58.6) | 1123 (83.6) | 1.34 (1.26, 1.41) | <0.001 | 1013 (81.6) | 1064 (86.7) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 0.03 |

| Singing to the child | 552 (43.4) | 797 (60.2) | 1.21 (1.12, 1.31) | <0.001 | 362 (31.5) | 600 (50.3) | 1.49 (1.34, 1.66) | <0.001 |

| Talking to the child | 1026 (80.1) | 1308 (97.7) | 1.19 (1.15, 1.24) | <0.001 | 1168 (93.5) | 1197 (97.4) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 0.008 |

1Values are n (%) for categorical variables and means ± SDs for continuous variables. When >5% of the sample is missing, the revised sample size is listed below. APR, adjusted prevalence ratio; IYCF, infant and young child feeding.

2Prevalence ratios, 95% CIs, and P values were obtained from log-binomial regression models that account for correlated errors within clusters using an exchangeable correlation structure. For continuous variables, the difference of means and corresponding 95% CI and P values were obtained from linear regression models also accounting for correlated errors within clusters using an exchangeable correlation structure. Models were adjusted for child's sex, caste, and age; maternal education; household food insecurity score; and household asset tertile.

3 n = 1173 and 1258 for baseline and endline in Kapilvastu; n = 1204 and 1158 for baseline and endline in Achham.

4In accordance with the UNICEF IYCF indicators, minimum dietary diversity is defined as feeding of ≥4 food groups (out of 7) in the previous 24 h. Minimum meal frequency is defined as ≥2 times/d for breastfed infants aged 6–8 mo, ≥3 times/d for breastfed children aged 9–23 mo, and ≥4 times/d for nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mo. Minimum acceptable diet is defined as minimum meal frequency and minimum dietary diversity in the previous 24 h for breastfed children; for nonbreastfed children, minimum acceptable diet is defined as ≥2 milk feedings, the minimum meal frequency, and ≥4 food groups (from a total of 6 food groups that excludes dairy) in the previous day.

5 n = 1171 and 1334 for baseline and endline in Kapilvastu; n = 1204 and 1220 for baseline and endline in Achham.

6 n = 1171 and 1248 for baseline and endline in Kapilvastu; n = 1204 and 1156 for baseline and endline in Achham.

In multivariable analyses from the endline survey, we found that mothers who received IYCF counseling and saw their FCHV more than once per month were significantly more likely to feed their children homemade “super flour” (APR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.07, 2.03; P = 0.02), the MMF (APR: 1.18; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.31; P = 0.004), and the MAD (APR: 1.47; 95% CI: 1.07, 2.03; P = 0.02) when compared with mothers who never received IYCF counseling from an FCHV, after adjustment for demographic characteristics, household access to health services (distance mother travels to see her FCHV and to her nearest health center), and maternal health-seeking behavior (whether she received home visits from her FCHV, attends FCHV meetings elsewhere, or both) (Table 3). We did not observe a significant association in these indicators when comparing mothers who received IYCF counseling from an FCHV but reported infrequent interactions (once per month or less) and mothers who never received IYCF counseling from an FCHV. Compared with mothers who never received IYCF counseling, mothers who received IYCF counseling (regardless of frequency of contacts) were, however, more likely to correctly answer nutrition-knowledge questions such as identifying 6 mo as the appropriate age to introduce complementary foods and identifying green leafy vegetables and pulses as good sources of iron.

TABLE 3.

Comparing maternal IYCF knowledge and reported practices at endline on the basis of maternal receipt of IYCF counseling from her FCHV and the frequency of mother-FCHV interactions: Kapilvastu and Achham districts, Nepal1

| Received IYCF counseling from FCHV and sees FCHV ≤1 time/mo (n = 1123) | Received IYCF counseling from FCHV and sees FCHV ≥2 times/mo (n = 898) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No IYCF counseling from FCHV (n = 557), n (%) (ref) | n (%) | APR (95% CI)2 | P | n (%) | APR (95% CI)2 | P | ||

| Maternal nutrition and IYCF knowledge | ||||||||

| Identifies 6 mo as appropriate age to introduce complementary foods | 398 (71.7) | 925 (82.7) | 1.09 (1.02, 1.17) | 0.01 | 799 (89.1) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | <0.001 | |

| Has heard of iron | 442 (79.4) | 060 (85.5) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 0.06 | 742 (82.6) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 0.72 | |

| Is able to identify a reason iron is important | 427 (76.7) | 943 (84.0) | 1.09 (1.01, 1.18) | 0.03 | 734 (81.7) | 1.04 (0.96, 1.13) | 0.35 | |

| Identifies the following as a source of iron | ||||||||

| Meat, fish, or liver | 292 (52.4) | 643 (57.3) | 1.13 (0.99, 1.30) | 0.08 | 522 (58.1) | 1.13 (0.98, 1.30) | 0.10 | |

| Pulses | 207 (37.2) | 536 (47.7) | 1.26 (1.09, 1.47) | 0.002 | 451 (50.2) | 1.24 (1.05, 1.46) | 0.01 | |

| Green leafy vegetables | 260 (46.7) | 640 (56.9) | 1.19 (1.04, 1.37) | 0.01 | 521 (58.0) | 1.17 (1.02, 1.34) | 0.03 | |

| Maternal report of IYCF practices | ||||||||

| Mother reports starting complementary foods at 6 mo | 333 (64.4) | 789 (72.0) | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) | 0.05 | 710 (80.7) | 1.18 (1.06, 1.31) | 0.002 | |

| Child consumed breast milk the previous day | 515 (93.1) | 1057 (95.0) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.18 | 866 (97.3) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 0.08 | |

| Child consumed (semi) solid food the previous day | 497 (96.1) | 1070 (97.5) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.53 | 850 (96.6) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.89 | |

| Child consumed (semi) solid food the previous day (in children aged 6–8 mo only)3 | 57 (87.7) | 69 (82.1) | 0.89 (0.76, 1.03) | 0.12 | 63 (78.8) | 0.86 (0.72, 1.02) | 0.09 | |

| Minimum dietary diversity4 | 196 (39.4) | 391 (36.5) | 0.96 (0.82, 1.13) | 0.63 | 383 (45.1) | 1.16 (0.98, 1.38) | 0.09 | |

| Minimum meal frequency4 | 242 (43.8) | 634 (57.0) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.17) | 0.22 | 554 (62.3) | 1.18 (1.05, 1.31) | 0.004 | |

| Minimum acceptable diet4 | 110 (22.3) | 265 (25.0) | 1.02 (0.82, 1.27) | 0.86 | 282 (33.5) | 1.33 (1.04, 1.68) | 0.02 | |

| Child ate homemade “super flour” the previous day | 56 (10.1) | 141 (12.6) | 1.09 (0.83, 1.44) | 0.54 | 182 (20.3) | 1.47 (1.07, 2.03) | 0.02 | |

| Mother reports the following responsive feeding activity in the previous day | ||||||||

| Eye contact with child | 478 (86.1) | 919 (82.0) | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.43 | 790 (88.4) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 0.25 | |

| Singing to the child | 308 (56.8) | 580 (52.7) | 0.94 (0.82, 1.07) | 0.33 | 509 (58.2) | 1.01 (0.89, 1.15) | 0.82 | |

| Talking to the child | 538 (96.9) | 1090 (97.5) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.04) | 0.14 | 877 (98.0) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | 0.07 | |

1 n (%) values are based on total n; when >5% of the sample is missing for an indicator, the revised sample size is listed below. APR, adjusted prevalence ratio; FCHV, female community health volunteer; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; ref, reference.

2Prevalence ratios and corresponding 95% CIs and P values were obtained from log-binomial regression models that account for correlated errors within clusters using an exchangeable correlation structure. Models were adjusted for child's sex, caste, and age; maternal education; household food insecurity score and household asset tertile; mother's access to health services (amount of time mother travels to see her FCHV and to go to her nearest health center); maternal health-seeking behavior (whether she received home visits from her FCHV, attends FCHV meetings elsewhere, or both); and whether the mother ever received IYCF counseling from a health worker.

3UNICEF indicator for timely introduction of complementary foods is defined as the proportion of children aged 6–8 mo who received solid or semisolid foods in the previous day. Sample sizes of children aged 6–8 mo among mothers who did not receive IYCF from her FCHV, those who received IYCF but had infrequent interactions, and mothers who received counseling and had frequent interactions are n = 65, 84, and 80 respectively.

4In accordance with the UNICEF IYCF indicators, minimum dietary diversity is defined as feeding of ≥4 food groups (out of 7) in the previous 24 h. Minimum meal frequency is defined as ≥2 times/d for breastfed infants aged 6–8 mo, ≥3 times/d for breastfed children aged 9–23 mo, and ≥4 times/d for nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mos. Minimum acceptable diet is defined as minimum meal frequency and minimum dietary diversity in the previous 24 h for breastfed children; for nonbreastfed children, minimum acceptable diet is defined as ≥2 milk feedings, the minimum meal frequency, and ≥4 food groups (from a total of 6 food groups that excludes dairy) in the previous day. Sample sizes for dietary diversity are n = 497, 1070, and 849 for mothers who did not receive IYCF counseling from their FCHV, those who received counseling but interacted with their FCHV infrequently, and those who received counseling and interacted frequently, respectively. Sample sizes for the same categories for minimum meal frequency and minimum acceptable diet are n = 553, 1112, and 889, and n = 493, 1060, and 841, respectively.

By contrast, we did not find significant differences in IYCF indicators when comparing mothers who received IYCF counseling from a health worker with those who did not receive health worker IYCF counseling, in models adjusted for demographic characteristics, maternal access to health services and health-seeking behavior, and whether the mother received IYCF counseling from an FCHV (Table 4). Of the IYCF indicators assessed, the only exception was that mothers who received IYCF counseling from a health worker were significantly more likely to identify pulses as a source of iron than were mothers who did not receive health worker IYCF counseling (APR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.27; P = 0.04).

TABLE 4.

Comparing maternal IYCF knowledge and reported practices at endline on the basis of whether the mother ever received IYCF counseling from an HW: Kapilvastu and Achham districts, Nepal1

| No IYCF counseling from HW (n = 942), | Received IYCF counseling from HW (n = 1629) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) (ref) | n (%) | APR (95% CI)2 | P | |

| Maternal nutrition and IYCF knowledge | ||||

| Identifies 6 mo as appropriate age to introduce complementary foods | 731 (77.6) | 1391 (85.4) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.05) | 0.76 |

| Has heard of iron | 767 (81.0) | 1377 (84.4) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.41 |

| Is able to identify a reason iron is important | 747 (78.9) | 1357 (83.2) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 0.28 |

| Identifies the following as a source of iron | ||||

| Meat, fish, or liver | 500 (52.8) | 957 (58.7) | 1.07 (0.98, 1.17) | 0.11 |

| Pulses | 379 (40.0) | 815 (50.0) | 1.13 (1.01, 1.27) | 0.04 |

| Green leafy vegetables | 477 (50.4) | 944 (57.9) | 1.07 (0.97, 1.18) | 0.17 |

| Maternal report of IYCF practices | ||||

| Mother reports starting complementary foods at 6 mo | 603 (66.7) | 1229 (77.3) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.11) | 0.06 |

| Child consumed breast milk the previous day | 887 (94.5) | 1551 (95.9) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.58 |

| Child consumed (semi) solid food the previous day | 870 (96.1) | 1547 (97.4) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 0.12 |

| Child consumed (semi) solid food the previous day (in children aged 6–8 mo only)3 | 71 (80.7) | 118 (83.7) | 1.10 (0.98, 1.24) | 0.10 |

| Minimum dietary diversity4 | 343 (39.5) | 627 (40.5) | 1.04 (0.92, 1.19) | 0.53 |

| Minimum meal frequency4 | 480 (51.2) | 950 (58.8) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.15) | 0.07 |

| Minimum acceptable diet4 | 222 (25.8) | 435 (28.3) | 1.09 (0.93, 1.28) | 0.27 |

| Child ate homemade “super flour” the previous day | 111 (11.7) | 268 (16.4) | 1.05 (0.81, 1.36) | 0.72 |

| Mother reported the following responsive feeding activity in the previous day | ||||

| Eye contact with child | 799 (84.6) | 1388 (85.4) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 0.67 |

| Singing to the child | 508 (55.0) | 889 (55.8) | 1.06 (0.97, 1.17) | 0.20 |

| Talking to the child | 919 (97.7) | 1586 (97.5) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.57 |

1 n (%) values are based on total n; when >5% of the sample is missing for an indicator, the revised sample size is listed below. APR, adjusted prevalence ratio; HW, health worker; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; ref, reference.

2Prevalence ratios and corresponding 95% CIs and P values were obtained from log-binomial regression models that account for correlated errors within clusters using an exchangeable correlation structure. Models were adjusted for child's sex, caste, and age; maternal education; household food insecurity score and household asset tertile; mother's access to health services (amount of time mother travels to see her FCHV and to go to her nearest health center); maternal health-seeking behavior (whether she received home visits from her FCHV, attends FCHV meetings elsewhere, or both); and whether the mother ever received IYCF counseling from a health worker.

3UNICEF indicator for timely introduction of complementary foods is defined as the proportion of children aged 6–8 mo who received solid or semisolid foods in the previous day. Sample sizes of children aged 6–8 mo among mothers who did not receive IYCF counseling from a health worker and those who did are n = 88 and 141, respectively.

4In accordance with the UNICEF IYCF indicators, minimum dietary diversity is defined as feeding of ≥4 food groups (out of 7) in the previous 24 h. Minimum meal frequency is defined as ≥2 times/d for breastfed infants aged 6–8 mo, ≥3 times/d for breastfed children aged 9–23 mo, and ≥4 times/d for nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mos. Minimum acceptable diet is defined as minimum meal frequency and minimum dietary diversity in the previous 24 h for breastfed children; for nonbreastfed children, minimum acceptable diet is defined as ≥2 milk feedings, the minimum meal frequency, and ≥4 food groups (from a total of 6 food groups that excludes dairy) in the previous day. Sample sizes for dietary diversity are n = 869 and 1547 for mothers who did not receive IYCF counseling from a health worker and mothers who did, respectively. Sample sizes for the same categories for minimum meal frequency are n = 937 and 1617, and for minimum acceptable diet are n = 859 and 1535, respectively.

We also found that receiving MNPs from an FCHV was independently associated with significant improvements in several indicators of IYCF knowledge and reported practices, even after adjusting for demographic characteristics, maternal access to health services, maternal health-seeking behavior, and whether the mother received IYCF counseling from an FCHV or health worker (Table 5). Specifically, mothers who received MNPs from their FCHV were significantly more likely to identify 6 mo as the appropriate age to introduce complementary foods and to report that they personally began feeding their child solid foods at 6 mo, compared with mothers who did not receive MNPs from their FCHV. This increase in the timely introduction of complementary foods was also reflected by the 20% increased likelihood that children aged 6–8 mo whose mothers received MNPs from their FCHV ate solid food in the previous day compared with children in the same age group whose mothers did not receive MNPs from an FCHV. Mothers who received MNPs from their FCHV were also significantly more likely to feed their children the MDD, MMF, and MAD [APR (95% CI): 1.27 (1.14, 1.40), 1.31 (1.19, 1.44), and 1.41 (1.21, 1.64) respectively].

TABLE 5.

Comparing maternal IYCF knowledge and reported practices at endline on the basis of whether the mother ever received MNPs from her FCHV for the child aged 6–23 mo, adjusting for receipt of IYCF counseling from FCHVs and health workers as well as other sociodemographic characteristics: Kapilvastu and Achham districts, Nepal1

| No MNP from FCHV (n = 1192), | Received MNP from FCHV (n = 1386) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) (ref) | n (%) | APR (95% CI)2 | P | |

| Maternal nutrition and IYCF knowledge | ||||

| Identifies 6 mo as appropriate age to introduce complementary foods | 930 (78.2) | 1192 (86.3) | 1.05 (1.00, 1.09) | 0.04 |

| Has heard of iron | 975 (81.8) | 1169 (84.3) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.08) | 0.22 |

| Is able to identify a reason iron is important | 962 (80.7) | 1142 (82.4) | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.53 |

| Identifies the following as a source of iron | ||||

| Meat, fish, or liver | 671 (56.3) | 786 (56.7) | 1.01 (0.93, 1.09) | 0.88 |

| Pulses | 524 (44.0) | 670 (48.3) | 1.02 (0.91, 1.13) | 0.78 |

| Green leafy vegetables | 622 (52.2) | 799 (57.7) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) | 0.50 |

| Maternal report of IYCF practices | ||||

| Mother reports starting complementary foods at 6 mo | 770 (69.4) | 1062 (76.8) | 1.06 (1.01, 1.13) | 0.04 |

| Child consumed breast milk the previous day | 1138 (96.0) | 1300 (94.9) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.34 |

| Child consumed (semi) solid food the previous day | 1045 (94.1) | 1372 (99.1) | 1.04 (1.03, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Child consumed (semi) solid food the previous day (in children aged 6–8 mo only)3 | 167 (81.1) | 22 (95.7) | 1.20 (1.06, 1.36) | 0.004 |

| Minimum dietary diversity4 | 350 (33.5) | 620 (45.2) | 1.27 (1.14, 1.40) | <0.001 |

| Minimum meal frequency4 | 477 (40.2) | 953 (69.7) | 1.31 (1.19, 1.44) | <0.001 |

| Minimum acceptable diet4 | 197 (18.9) | 460 (34.0) | 1.41 (1.21, 1.64) | <0.001 |

| Child ate homemade “super flour” the previous day | 131 (11.0) | 248 (17.9) | 1.58 (1.28, 1.94) | <0.001 |

| Mother reported the following responsive feeding activity in the previous day | ||||

| Eye contact with child | 1024 (86.1) | 1163 (84.3) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.03) | 0.63 |

| Singing to the child | 644 (55.4) | 753 (55.6) | 1.02 (0.94, 1.11) | 0.58 |

| Talking to the child | 1160 (97.7) | 1345 (97.4) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.34 |

1 n (%) values are based on total n; when >5% of the sample is missing for an indicator, the revised sample size is listed below. APR, adjusted prevalence ratio; FCHV, female community health volunteer; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; MNP, micronutrient powder; ref, reference.

2Prevalence ratios and corresponding 95% CIs and P values were obtained from log-binomial regression models that account for correlated errors within clusters using an exchangeable correlation structure. Models were adjusted for child's sex, caste, and age; maternal education; household food insecurity score and household asset tertile; mother's access to health services (amount of time mother travels to see her FCHV and to go to her nearest health center); maternal health-seeking behavior (whether she received home visits from her FCHV, attends FCHV meetings elsewhere, or both); and whether the mother ever received IYCF counseling from an FCHV or health worker.

3UNICEF indicator for timely introduction of complementary foods is defined as the proportion of children aged 6–8 mo who received solid or semisolid foods in the previous day. Sample sizes of children aged 6–8 mo among mothers who did not receive MNP from her FCHV and those who did are n = 206 and 23, respectively.

4In accordance with the UNICEF IYCF indicators, minimum dietary diversity is defined as feeding of ≥4 food groups (out of 7) in the previous 24 h. Minimum meal frequency is defined as ≥2 times/d for breastfed infants aged 6–8 mo, ≥3 times/d for breastfed children aged 9–23 mo, and ≥4 times/d for nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mo. Minimum acceptable diet is defined as minimum meal frequency and minimum dietary diversity in the previous 24 h for breastfed children; for nonbreastfed children, minimum acceptable diet is defined as ≥2 milk feedings, the minimum meal frequency, and ≥4 food groups (from a total of 6 food groups that excludes dairy) in the previous day. Sample sizes for dietary diversity are n = 1045 and 1371 for mothers who did not receive MNP from their FCHV and mothers who did, respectively. Sample sizes for the same categories for minimum meal frequency are n = 1186 and 1368, and for acceptable diet are n = 1040 and 1354, respectively.

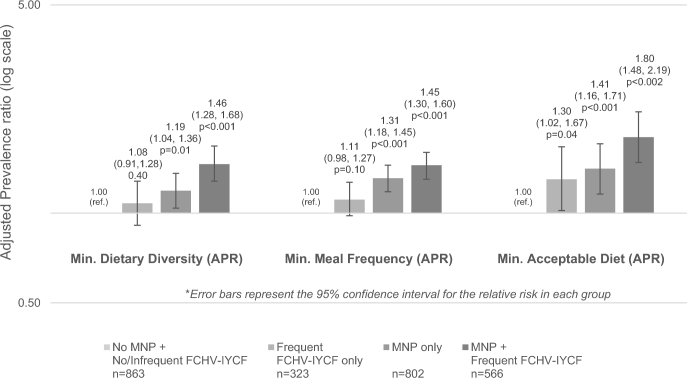

In models containing an interaction term for receiving MNPs from an FCHV plus IYCF counseling from an FCHV with frequent interactions, we did not find that the interaction term was significant for models for MDD, MMF, or MAD, although mothers who received IYCF counseling from an FCHV with frequent interactions and received MNPs from her FCHV were the most likely to feed their children the MDD, MMF, and MAD (Figure 2). Pairwise comparisons indicated that mothers who received IYCF counseling from an FCHV with frequent interactions and received MNPs from her FCHV were significantly more likely to feed her child the MDD, MMF, and MAD than mothers who did not receive FCHV IYCF counseling or received it with infrequent interactions and who also did not receive MNPs from her FCHV.

FIGURE 2.

Comparing maternal report of IYCF practices at endline on the basis of whether the mother received IYCF counseling from an FCHV, accounting for frequency of mother-FCHV interactions, and whether the FCHV provided MNPs to mothers of children aged 6–23 mo in Kapilvastu and Achham districts, Nepal. APRs and corresponding 95% CIs and P values were obtained from log-binomial regression models that accounted for correlated errors within clusters with the use of an exchangeable correlation structure. Models were adjusted for child's sex, caste, and age; maternal education; household food-insecurity score and household asset tertile; as well as household access to health services (time mother spends traveling to see her FCHV and to her nearest health center); maternal health-seeking behavior (whether she received home visits from her FCHV, sees an FCHV elsewhere, or both); and whether the mother ever received IYCF counseling from a health worker. In accordance with the UNICEF IYCF indicators, minimum dietary diversity is defined as feeding of ≥4 food groups (out of 7) in the previous 24 h. Minimum meal frequency is defined as ≥2 times/d for breastfed infants aged 6–8 mo, ≥3 times/d for breastfed children aged 9–23 mo, and ≥4 times/d for nonbreastfed children aged 6–23 mo. Minimum acceptable diet is defined as minimum meal frequency and minimum dietary diversity in the previous 24 h for breastfed children; for nonbreastfed children, minimum acceptable diet is defined as ≥2 milk feedings, the minimum meal frequency, and ≥4 food groups (from a total of 6 food groups that excludes dairy) in the previous day. APR, adjusted prevalence ratio; FCHV, female community health volunteer; Frequent FCHV-IYCF only, mothers who report receiving IYCF counseling from an FCHV and seeing the FCHV ≥2 times/mo but who report not receiving MNP from the FCHV; IYCF, infant and young child feeding; MNP, micronutrient powder; MNP only, mothers who received MNP from their FCHV but report either not receiving IYCF counseling from an FCHV or receiving FCHV-IYCF counseling with infrequent (once per month or less) interactions with their FCHV; MNP + frequent FCHV-IYCF, mothers who report receiving MNP from their FCHV and also report receiving IYCF counseling from the FCHV with frequent FCHV interactions (≥2 times/mo); No MNP + No/infrequent FCHV-IYCF, mothers who report they did not receive MNP from their FCHV and either never received IYCF counseling from an FCHV or received FCHV-IYCF counseling but with infrequent (once per month or less) interactions with their FCHV.

We also found that mothers who received MNPs from their FCHV were 1.43 (95% CI: 1.17, 1.75; P < 0.001) times more likely than mothers who did not receive MNPs from their FCHV to report being “very satisfied” with their FCHVs, even after adjustment for demographic characteristics, maternal health-seeking behaviors, household access to health services, and receipt of FCHV IYCF counseling. Furthermore, among those who used MNPs, mothers who identified a positive change in their child were 1.61 (95% CI: 1.31, 1.98; P < 0.001) times more likely to report being “very satisfied” with their FCHV. Compared with mothers who were satisfied, unsatisfied, or very unsatisfied with their FCHV, mothers who were “very satisfied” with their FCHVs were more likely to feed their children the MAD in multivariable models (APR: 1.22; 95% CI: 1.07, 1.39; P = 0.004). However, in the formal mediation analysis, maternal satisfaction only explained 5.5% (95% CI: 0.7%, 33.7%; P = 0.17) of the relation between receiving MNPs from an FCHV and feeding the child the MAD.

Discussion

In this analysis representative of children aged 6–23 mo and their mothers from 2 districts in Nepal where an integrated IYCF-MNP program was implemented, we found that several key IYCF knowledge and reported practice indicators were significantly more prevalent in the endline survey than in the baseline survey. We also found that receipt of IYCF counseling from an FCHV with frequent maternal-FCHV interactions was positively associated with key IYCF knowledge and reported practices. After adjustment for receipt of IYCF counseling from an FCHV and sociodemographic characteristics, we did not, however, find that receipt of counseling from a health worker had an independent relationship with IYCF practices. Receipt of MNPs from the FCHV did, however, have an independent relationship with several key IYCF practices, including the timely introduction of complementary foods and feeding the child the MDD, MMF, and MAD, even after adjustment for receipt of IYCF counseling from an FCHV and/or health worker.

The FCHV program, which includes ∼50,000 FCHVs throughout Nepal, is one of the largest and most well-regarded community health cadres globally (38–40). To our knowledge, our study is the first to assess the role of FCHVs in improving IYCF practices in Nepal. Interestingly, we found that mothers who received IYCF from their FCHV but reported infrequent interactions (once per month or less) were more likely to correctly answer several IYCF knowledge questions (compared with mothers who never received IYCF counseling); however, only mothers who received IYCF counseling and had frequent FCHV contact (more than once per month) were significantly more likely to report engaging in key IYCF practices, such as feeding the child homemade super flour and feeding the child the MMF and MAD. We also did not find an independent association between health worker IYCF counseling and IYCF practices. Our findings highlight the importance of follow-up through frequent interactions between mothers and FCHVs to achieve complex changes in behavior; they provide evidence that future programs may need to promote regular maternal-CHW interactions beyond the common once-per-month structure in order to improve IYCF practices. In the endline survey, approximately one-third of mothers in the 2 districts reported interacting with the FCHV at least twice per month, indicating that promotion of frequent FCHV mother interactions may be a realistic strategy in Nepal and other settings. Although mothers may have interacted with an FCHV for multiple reasons not necessarily focused on IYCF issues, the frequent contacts may strengthen the trust and communication between mothers and their FCHVs and also afford additional opportunities to discuss or troubleshoot IYCF-MNP issues.

Our study also indicates that the addition of MNPs into the IYCF program in Nepal may have had added benefits for IYCF knowledge and practices beyond what was achieved through FCHV-IYCF counseling alone. In multivariable models, accounting for receipt of IYCF counseling from an FCHV, maternal health-seeking behavior, the time mothers spent traveling for FCHV meetings and to their nearest health facility, as well as key sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., maternal education and household food security level), we still found that mothers who received MNPs from their FCHV were more likely to engage in several optimal IYCF practices.

The mechanisms through which MNPs may have independently contributed to maternal IYCF practices warrant further research. One plausible explanation is that the integration of MNPs into the IYCF program in Nepal could have improved IYCF practices by re-enforcing key IYCF messages through the additional IYCF-MNP training for FCHVs and health workers and through the introduction of new MNP brochures, radio messages, and other communications materials. These additional strategies may have also influenced secondary audiences in the districts, creating an enabling community and home environment among other key stakeholders who could support the mother and child to practice improved IYCF and consume MNPs. Introducing a novel, tangible item for the FCHVs to provide to mothers in their community may also have provided an additional incentive for mothers to discuss IYCF with their FCHV and may have also improved FCHV motivation and performance. A recent review of programs delivered by CHWs found that CHWs reported feeling more community recognition and motivation when they were able to provide physical goods and curative services to their communities (41). Although we did not assess FCHV motivation in the impact evaluation, we did find that mothers who received MNPs from their FCHV, especially those who reported a positive effect of MNPs, were significantly more likely to report being “very satisfied” with the performance of their FCHV than mothers who did not receive MNPs from an FCHV. It is possible that this finding is due to reverse causation (i.e., high-quality FCHVs may have been more likely to provide MNPs and counseling to mothers on what positive changes to expect), but it may also be due to the role of MNPs in enhancing the quality of IYCF counseling, changing maternal perceptions of her FCHV, observed positive effects in her child, or other reasons. Our formal mediation analysis showed that maternal satisfaction only accounted for 5.5% of the association between receipt of MNPs from an FCHV and the probability that the mother would feed her child the MAD; however, our indicator was limited. Very few mothers in our study sample reported being unsatisfied with their FCHV; thus, we were only able to compare “very satisfied” with all other levels of satisfaction. Notably, 15 mo after the initiation of the pilot IYCF-MNP project in Nepal, 57% of FCHVs in districts with an FCHV delivery model and 44% of FCHVs in districts with the health facility model reported needing more support or disliking the added work of MNPs (21). FCHV characteristics (e.g., education, literacy, capacity, and familial support) and performance vary by district in Nepal, and this may be the case for CHWs in other settings as well. Future research and monitoring at the FCHV level are necessary to elucidate how the introduction of MNPs affects FCHV motivation and performance, as well as how this changes with the provision of adequate supervision and support, and also over time as IYCF-MNP programs mature (28).

Interestingly, we found that receiving MNPs from the FCHV was independently associated with several different indicators of IYCF practices including those that the program hypothesized might be associated with MNP use. For example, it has been hypothesized that MNP programs may support the timely introduction of complementary foods, because MNP behavior-change messages focus on the introduction of MNPs and solid and semisolid foods starting at 6 mo (29); however, previously, there has been little evidence to support this premise (30, 31). In the IYCF-MNP program package in Nepal, the counseling and messages prompted families to exclusively breastfeed for the first 6 mo of life, and then at 6 mo of age, to start semisolid and solid complementary food intake with MNPs and continued breastfeeding thereafter. In this analysis, we found that 94% of mothers in Kapilvastu and 97% of mothers in Achham had breastfed their child the previous day in both baseline and endline surveys, indicating that the intervention did not change the already very high prevalence of continued breastfeeding for children aged 6–23 mo in the 2 intervention districts. We did find, however, that mothers who received MNPs from their FCHV were significantly more likely than mothers who did not receive MNPs from their FCHV to identify 6 mo as the appropriate age to introduce complementary foods and to report introducing complementary foods to their child at 6 mo. Furthermore, among mothers of children aged 6–8 mo, those who received MNPs from their FCHV were significantly more likely to report feeding their children solid or semisolid foods in the previous day (the WHO indicator for timely initiation of complementary feeding). It has also been hypothesized that MNP programs can support active and responsive feeding behaviors because mothers may be motivated to encourage their child to eat the portion of food with the MNP (29). Although our study found that responsive feeding behaviors increased from baseline to endline, we did not find that FCHV-IYCF counseling or the receipt of MNPs from the FCHV was associated with any of the responsive feeding indicators assessed in this study.

Our study design is limited because of its observational nature and lack of a control group. In addition, due to the cross-sectional nature of the baseline and endline surveys, it is possible some of the differences between baseline and endline in IYCF knowledge and practices were due to secular trends not related to any of the IYCF programs in the 2 districts. We did, however, find significant differences in IYCF knowledge and practices comparing mothers who received IYCF counseling from an FCHV with frequent FCHV interactions (and a moderate dose-response for some indicators based on frequency of mother-FCHV interactions), thus indicating that the observed changes may be attributable to the IYCF programs that utilized the FCHVs. In analyses assessing the impact of receiving IYCF counseling from an FCHV or health worker, as well as the impact of receiving MNPs from an FCHV, we were further limited by the lack of randomization of our exposures, which prevents the attribution of causality. Underlying differences between mothers who received IYCF counseling from an FCHV or health worker compared with those who did not, or among mothers who received MNPs from her FCHV compared with those who did not, may ultimately be confounding the association between program exposure and IYCF practices. We did, however, adjust for several key demographic covariates, including district, maternal literacy, and socioeconomic variables, as well as for maternal health-seeking and health service access indicators, and this did not substantially change our findings. Finally, we were also limited by the fact that the evaluation focused on household surveys only. We did not include qualitative research or FCHV- or provider-level assessment, which might have further elucidated some of the mechanisms for the associations found in this article. In addition, all data are from maternal report and subject to various biases, including social desirability and time recall.

Our study also has several strengths. Unlike many other studies published from pilot IYCF-MNP programs (18), our surveys were conducted in 2 rural districts in Nepal that were part of the national scale-up of the integrated IYCF-MNP intervention, thus elucidating the potential impacts of an integrated IYCF-MNP program during the process of scale-up. Our survey used representative sampling of children aged 6–23 mo from the 2 districts and included particularly large sample sizes at both baseline and endline. We collected thorough data on program exposures and maternal IYCF knowledge and practices, as well as several sociodemographic confounders, all of which allowed for rigorous multivariable analyses. In addition, in our statistical analyses, we used log-binomial regression models to directly estimate prevalence ratios; logistic regression models would have estimated ORs, which would have overestimated the associations observed in our study, particularly given the high prevalence of the IYCF outcomes assessed in this study (42, 43).

In conclusion, we found that from 2013 until 2016, many IYCF practices among children aged 6–23 mo improved in 2 intervention districts that were part of the scale-up of an integrated IYCF-MNP program in Nepal. During the time period assessed, multiple IYCF programs, namely Suaahara and the integrated IYCF-MNP program, were co-located in Kapilvastu and Achham, and both aimed to strengthen the IYCF platform with a particular focus on FCHVs. In our analysis, we found that mothers who received IYCF counseling from an FCHV with frequent mother-FCHV contacts were significantly more likely to engage in optimal IYCF practices than mothers who did not receive FCHV-IYCF counselling. We also found an independent association between maternal receipt of MNPs from her FCHV and select IYCF practices. In this setting, the incorporation of MNPs into the IYCF interventions provided additional micronutrients from MNPs and did not appear to harm IYCF practices; rather, the addition of MNPs may have contributed to improvements in select IYCF practices. Given the potential synergies between IYCF and MNP programs, particularly the overlapping objectives, target populations, and potential delivery channels, future research that uses an experimental design should verify the potential of integrated IYCF-MNP programs to improve IYCF practices.

Acknowledgments

We thank Shyam Raj Uprety, Senendra Raj Uprety, Krishna Poudel, Rajendra Kumar Pant, Giri Raj Subedi, Saba Mebrahtu, Sanjay Rijal, Rajni Gunnala, and Cria Perrine for their work on implementing and evaluating this program. The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—MEJ, PD, ZM, and RDW: designed the evaluation; PD, RP, SC, NP, NJ, and BL: oversaw the program implementation; PD, RP, SC, NP, NJ, BL, MEJ, ZM, and RDW: provided training, supervision, and support of data collectors and provided interpretation and approval of analyses; LML: analyzed data; LML, AG, and MEJ: wrote the manuscript and had primary responsibility for final content; and all authors: read and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest related to this article.

Notes

The Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population, and UNICEF Nepal Country Office supported the implementation of the intervention. UNICEF Nepal funded an external agency (New ERA) to conduct the baseline and endline surveys.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC, UNICEF, or the Government of Nepal.

Author disclosures: LML, PD, RP, NJ, NP, RDW, SC, ZM, BL, AG, and MEJ, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used:

- APR

adjusted prevalence ratio

- CHW

community health worker

- FCHV

female community health volunteer

- IYCF

infant and young child feeding

- MAD

minimum acceptable diet

- MDD

minimum dietary diversity

- MMF

minimum meal frequency

- MNP

micronutrient powder

- MoH

Ministry of Health

References

- 1. Micronutrient Initiative. Investing in the future: a united call to action on vitamin and mineral deficiencies. Ottawa (Canada): Micronutrient Initiative;2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stevens GA, Bennett JE, Hennocq Q, Lu Y, De-Regil LM, Rogers L, Danaei G, Li G, White RA, Flaxman SR, et al. Trends and mortality effects of vitamin A deficiency in children in 138 low-income and middle-income countries between 1991 and 2013: a pooled analysis of population-based surveys. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3(9):e528–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stevens GA, Finucane MM, De-Regil LM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, Branca F, Peña-Rosas JP, Bhutta ZA, Ezzati M. Global, regional, and national trends in haemoglobin concentration and prevalence of total and severe anaemia in children and pregnant and non-pregnant women for 1995–2011: a systematic analysis of population-representative data. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1(1):e16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Black RE, Victora CG, Walker SP, Bhutta ZA, Christian P, de Onis M, Ezzati M, Grantham-McGregor S, Katz J, Martorell R. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013;382(9890):427–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. WHO Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO;2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown K, Dewey K, Allen L. Complementary feeding of young children in developing countries: a review of current scientific knowledge. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO;1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murphy SP, Allen LH. Nutritional importance of animal source foods. J Nutr 2003;133(11 Suppl):3932S–5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dewey KG, Adu‐Afarwuah S. Systematic review of the efficacy and effectiveness of complementary feeding interventions in developing countries. Matern Child Nutr 2008;4(s1):24–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. UNICEF From the first hour of life: a new report on infant and young child feeding. New York: UNICEF; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Population Division, Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal; New ERA; ICF International. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey. Kathmandu (Nepal);Government of Nepal: Ministry of Health (MOH); 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neufeld LM, Ramakrishnan U. Multiple micronutrient interventions during early childhood: moving towards evidence-based policy and program planning. J Nutr 2011;141(11):2064–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Allen LH, Peerson JM, Olney DK. Provision of multiple rather than two or fewer micronutrients more effectively improves growth and other outcomes in micronutrient-deficient children and adults. J Nutr 2009;139(5):1022–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Christian P, Tielsch JM. Evidence for multiple micronutrient effects based on randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses in developing countries. J Nutr 2012;142(1 Suppl):173S–7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zlotkin SH, Schauer C, Christofides A, Sharieff W, Tondeur MC, Hyder SZ. Micronutrient sprinkles to control childhood anaemia. PLoS Med 2005;2(1):e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De-Regil LM, Suchdev PS, Vist GE, Walleser S, Peña-Rosas JP. Home fortification of foods with multiple micronutrient powders for health and nutrition in children under two years of age [review]. Evid Based Child Health 2013;8(1):112–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. WHO WHO guideline: use of multiple micronutrient powders for point-of-use fortification of foods consumed by infants and young children aged 6–23 months and children aged 2–12 years. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. UNICEF Nutridash 2013: global report on the pilot year. New York: UNICEF; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reerink I, Namaste SM, Poonawala A, Nyhus Dhillon C, Aburto N, Chaudhery D, Kroeun H, Griffiths M, Haque MR, Bonvecchio A. Experiences and lessons learned for delivery of micronutrient powders interventions. Matern Child Nutr 2017;13(Suppl 1):e12495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rah JH, dePee S, Kraemer K, Steiger G, Bloem MW, Spiegel P, Wilkinson C, Bilukha O. Program experience with micronutrient powders and current evidence. J Nutr 2012;142(1 Suppl):191S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirve S, Martini E, Juvekar SK, Agarwal D, Bavdekar A, Sari M, Molwane M, Janes S, Haselow N, Yeung DL, et al. Delivering Sprinkles Plus through the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) to reduce anemia in pre-school children in India. Indian J Pediatr 2013;80(12):990–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jefferds MED, Mirkovic KR, Subedi GR, Mebrahtu S, Dahal P, Perrine CG. Predictors of micronutrient powder sachet coverage in Nepal. Matern Child Nutr 2015;11(Suppl 4):77–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]